Abstract

The homicides committed by women make up between 5 and 15% of the total number of homicides recorded in the world. Studies based on the gender of the perpetrator have been uncommon due to the low level of prevalence of female homicide offenders, but this tendency is currently undergoing a change. Nonetheless, in general, there is still limited knowledge of the role of women in serious crime, which makes the task of criminal policy more difficult. Therefore, the present investigation seeks to perform a comparative analysis of the homicides committed by women (n = 56) with those committed by men (n = 521). The cases in this sample correspond to homicides solved in Spain by the Civil Guard between the years 2013 and 2018. The findings of the study show that homicides by women have distinctive characteristics, with 3 out of every 4 taking place in the family environment, and these being dominated by cases of filicide. The victims are underage males with some type of vulnerability and a mental disorder. The female perpetrators tend to have a partner and live with somebody, have a mental disorder and do not present a prior criminal record. With regard to the crime, homicides perpetrated by women take place in the afternoon, without witnesses and in residences; when it comes to the criminal behaviours, they use weapons of opportunity, above all asphyxiating methods, they alter the scene and do not flee from the scene of the crime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The study of criminal behaviour shows that the majority of crimes, especially violent ones, are committed by men (Beatton et al., 2018; Côté, 2007; de Vogel & de Spa, 2019; Jackson & Motley, 2019; van der Heijden & Pluskota, 2018). In Spain, the average crime rate of men between the years 2010 and 2018 was five times higher than that of women (13.7 vs. 2.6 for every 100,000 inhabitants respectively) (National Statistics Institute [INE], 2019). And in the case of homicides, this difference was almost seven times greater (1.3 vs. 0.2) (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2019; González et al., 2018). Despite the differences reflected by these figures, a constant rise in the number of women convicted of violent crimes has been registered throughout the last 20 years (de Vogel & de Spa, 2019). But investigations on homicide have not produced conclusive results, seeing as the study by Putkonen et al. (2011) in Finland found an increase in homicides committed by women between the years 1995 and 2004, whilst the study by Trägårdh et al. (2016) in Sweden reported a tendency towards stability between 1990 and 2010, and the study by Cooper and Smith (2011) in the USA found a drop in numbers between 1980 and 2008, in line with what has occurred in Spain between the years 2010 and 2018 (INE, 2019). Despite these discrepancies, global studies agree that between 5 and 15% of recorded homicides are committed by women (Cooper & Smith, 2011; González et al., 2018; Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009; Liem & Pridemore, 2014; Pizarro et al., 2011; Santos et al., 2019; UNODC, 2019).

Whilst the study of women as victims of homicide has been broadly documented, even in Spain (Linde, 2019), the same cannot be said for the category of perpetrators. One of the main reasons for this is the low level of prevalence of female murderers (Eriksson et al., 2018; Fox & Fridel, 2017; Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009; Yourstone, et al., 2008). Traditionally, studies that have addressed the analysis of the phenomenon of homicide and those that have been undertaken with the objective of creating typologies have looked exclusively at homicides committed by men, or, if they have included homicides perpetrated by women, the fact that there are so few cases has meant that the distinctive characteristics of these cases remain hidden. It is for this reason that investigation in the fields of forensics and criminology and the development of prevention tools and treatment programmes have been based on the study of masculine populations, making their application to women questionable (Caman et al., 2016; de Vogel & de Spa, 2019).

Although in recent years, studies have been published that analyse the role of the woman as a perpetrator of homicide, these are still limited to cases that occur in the domestic sphere, and in which the woman kills her intimate partner (Belknap et al., 2012; Suonpää & Savolainen, 2019) or children (Liem & Koenraadt, 2008); or cases in which the women present some kind of mental disorder (Carabellese et al., 2020; Flynn et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2019). There are very few investigations that analyse the homicides committed by women outside of the family setting. In this respect, it is worth highlighting the study by Moen et al. (2016) that analysed 124 cases of female murderers in Sweden and which revealed that in 24% of the cases, they killed people outside of the family environment; and the study by Kim et al. (2017) in which the authors propose a typology of homicides committed by women based on the study of 362 cases committed in South Korea. Lastly, there are studies that have compared homicides committed by men with those committed by women (e.g. Sea et al., 2017) and that consistently show that there are significant differences in the profiles of victim and perpetrator as well as in the contextual factors and the manner in which the homicides are carried out.

Homicides Committed by Women vs. Homicides Committed by Men

Characteristics of the Victims

One of the main conclusions drawn by the studies that compare homicides committed by women and men is that women primarily kill family members, whilst men tend to kill acquaintances and strangers (Eckhardt & Pridemore, 2009; Flynn et al., 2011; González et al., 2018; Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009; Sea et al., 2017; Trägårdh et al., 2016). With regard to the gender of the victims, the majority of studies show that women just as much as men predominantly victimise the latter (Pizarro et al., 2010; Trägårdh et al., 2016), although the study by Sea et al. (2017) did find that women mainly kill men and men mainly kill women. The age of the victims has also been the subject of investigation, and although there seems to be a consensus on the fact that victims of a young age tend to be associated with women, mainly due to the involvement of the latter in cases of filicide (Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009; Moen et al., 2016; Nagata et al., 2016; Trägårdh et al., 2016), the study by Pizarro et al. (2010) found that the victims of women are older than those of male murderers, although other studies did not find significant differences in the ages of the victims (Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009; Sea et al., 2017). Finally, the study by Sea et al. (2017) also found no differences in the employment situation of the victims of men and women.

Characteristics of the Perpetrators

The link between the age of the murderers and their gender does not produce consistent results. There are studies that suggest that women who kill are older than male killers (Flynn et al., 2011; Fox & Fridel, 2017; Pizarro et al., 2010; Putkonen et al., 2011; Trägårdh et al., 2016; Yourstone et al., 2008) and others that find no substantial differences (Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009; Nagata et al., 2016; Sea et al., 2017). It is important to point out that when analysing specific typologies of homicide, such as the cases of women who kill their children or strangers, these women are younger than those who kill their partners (Moen et al., 2016). Consequently, it is clear that age is influenced by the context of the homicide and by the existing relationship between victim and perpetrator. Although few studies provide data about the country of origin of the female and male perpetrators of homicide, a consensus has been reached that the women tend to be national citizens, with a higher likelihood of the men being foreigners (Moen et al., 2016; Trägårdh et al., 2016; Yourstone et al., 2008). What is more, it is more common for the men to be unemployed at the time of the incident (Flynn et al., 2011; Putkonen et al., 2011; Sea et al., 2017). The women tend to be married or in a relationship and live with other people, whilst the men are usually single and live alone (Flynn et al., 2011; Sea et al., 2017; Trägårdh et al., 2016). When it comes to the existence of a criminal background, according to studies, this is less associated with women than with men (Flynn et al., 2011; Putkonen et al., 2011; Sea et al., 2017; Trägårdh et al., 2016). With regard to the consumption of alcohol and drugs, it is also more likely for the men to have consumed some type of substance at the time of the facts (Eckhardt & Pridemore, 2009; Moen et al., 2016), although these differences are not always significant (Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009). One aspect that has generated extensive research is the existence of a history of psychiatric illness and mental disorders amongst the women. Although studies associate different disorders with the women and men who kill, in general, it is more likely to be the women who exhibit some kind of previous diagnosis (Flynn et al., 2011; Nagata et al., 2016; Putkonen et al., 2011; Trägårdh et al., 2016). The existence of prior suicide attempts is also more frequently associated with women (Nagata et al., 2016) although the study by Trägårdh et al. (2016) found no significant differences in the consummation of suicide after the fact.

Characteristics of the Event

As far as the characteristics of the incident, the literature finds that women primarily carry out the homicides in indoor settings, especially in homes, whilst those committed by men take place in outdoor settings and other public places (Eckhardt & Pridemore, 2009; Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009; Moen et al., 2016; Trägårdh et al., 2016). No differences have been found regarding the number of victims (Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009). With reference to the weapon used, it appears evident that men use firearms to a greater extent than women (Fox & Fridel, 2017; Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009; Moen et al., 2016), but in terms of other kinds of weapons, studies have produced different results. The study by Trägårdh et al. (2016) found that blunt objects and asphyxiation were more commonly used by men, and the study by Flynn et al. (2011) associated bladed weapons with women, in contrast to the findings by Sea et al. (2017), which associated bladed weapons with men. Despite these discrepancies, the majority of studies associate asphyxiation with women, especially in cases of victims who are minors (Fox & Fridel, 2017; Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009; Moen et al., 2016). With regard to the nature of the weapon, whilst the study by Sea et al. (2017) showed that there are no differences when it comes to bearing arms prior to the incident, it did show that women are more likely to commit homicide using weapons available at the scene. Women, furthermore, demonstrate more behaviours of displacement and concealment of the body, they remain at the scene and they tend to confess to the homicide to a greater extent than men (Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009). Finally, there are no differences in terms of whether the place of the homicide and the discovery of the body are the same (Sea et al., 2017).

Aims of the Study

Traditionally, studies based on the gender of the perpetrator have been few and far between, given that most studies have focused on the homicides committed by men, or have simply disregarded the gender of the perpetrator. This tendency is undergoing a shift in the present day, since more and more investigations are analysing the role of the woman as the perpetrator of homicide, either studying cases solely perpetrated by women, or comparing these cases with those committed by men. Nonetheless, in general, there is still limited knowledge of the role of women in serious crime, which makes the task of criminal policy more difficult (Caman et al., 2016; de Vogel & de Spa, 2019; Eriksson et al., 2018).

The objective of the present investigation is to go into greater depth on the differences between the homicides committed by women and by men, but without limiting the sample to a specific scope, such as the cases of intimate partner homicide, or studying only the cases in which the female perpetrator exhibits some kind of distinctive characteristic, such as the existence of mental illness. The study will elaborate equally on the profile of the victims as well as that of the perpetrators, in addition to the contextual characteristics of the event and the criminal behaviours prior to and following the homicide.

Lastly, analyses have been carried out considering only the variables of the victims and the characteristics of the event, given that this is the information that police investigators rely on when launching an investigation. Braga and Dusseault (2018) demonstrated that the role of the police investigators has a direct impact on the rate of crimes that are solved; therefore, one of the main objectives of this type of study should be to equip the police investigators with knowledge that can be applied in new cases of homicide. Specifically, this work analyses the link between the information that can be obtained during the first moments of the police investigation and the gender of the perpetrator, making it possible to assess whether, in light of the characteristics of the victim and the incident, it is more likely that the perpetrator is a man or a woman, which will allow police to open up or prioritise lines of investigation.

Method

Sample

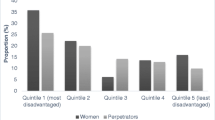

The cases analysed correspond to homicides solved by the Judicial Police Units of the Civil Guard between the years 2013 and 2018. During this time frame, a total of 604 homicides were recorded, of which only the 577 solved in this same time frame were included in the study (95.5%). The temporal distribution by year was the following: 100 in 2013 (17.3%), 89 in 2014 (15.4%), 105 in 2015 (18.2%), 95 in 2016 (16.5%), 81 in 2017 (14%) and 107 in 2018 (18.5%). With regard to the territorial distribution, it is worth mentioning that the Civil Guard is one of the Spanish state’s security forces. The national territory in which this police force carries out its security and investigation functions encompasses populations of fewer than 50,000 inhabitants and the outskirts of the provincial capitals (approximately 85% of the national territory).

The final sample included 577 victims and 542 perpetrators. The mean age of these victims was 45.7 years (SD = 21.397, range = 0–99, Mdn = 44), whereby 49 of the victims recorded were minors (8.5%). The victims were mainly men (59.3%) and of Spanish nationality (72.4%), with the foreign victims mainly being from the following countries: Morocco (5%), Romania (3.8%) and the UK (2.3%). In turn, the mean age of the perpetrators was 41.4 years (SD = 15.270, range = 16–91; Mdn = 40), with just 9 underage perpetrators recorded (1.7%). The perpetrators were predominantly men (90.2%) and of Spanish nationality (70.5%), with the foreign perpetrators mainly originating from Romania (9%) and the UK (2.4%).

Procedure

Various systems of police management and Civil Guard information were utilised in the collection of data, as was the information provided by the Organic Units of Judicial Police responsible for each of the cases of homicide. Subsequently, all the data was processed so as to standardise the codification of the information. Although information was gathered on all of the homicides recorded in the aforementioned police systems, once the base was put together, a filtering of the cases was undertaken so as to include only the following: (a) cases that had been solved and (b) intentional homicides or murders, excluding cases of involuntary manslaughter. In Spain, involuntary manslaughter refers to cases in which the death is caused by serious negligence or recklessness, but without wilful intent on the part of the perpetrator. Due to this lack of wilful intent, these cases are not of great interest from the perspective of a police investigation.

A case of homicide was understood to mean the specific interaction between a perpetrator and a victim, regardless of whether other people were involved in the event. In the homicides where more than one perpetrator was implicated, the data was codified for the person who was considered the principal perpetrator of the crime in the police investigation (the person who carried out the lethal act). In the incidents where more than one victim was recorded, the number of entries codified in the database was equivalent to the number of victims identified. These considerations were taken into account when the analyses were performed, varying the number of total cases in accordance with the type of variable analysed in each instance.

Variables

Victim and Perpetrator Variables

With regard to the victims and perpetrators, the following socio-demographic variables were included: gender (1 = Man; 2 = Woman), age indicated in years and in a dichotomous manner, whereby in Spain, underage is defined as less than 18 years old (1 = Minor; 2 = Adult) and the difference in age indicated in years between victim and perpetrator, the origin (1 = Spanish; 2 = Foreigner), the marital status (1 = Single; 2 = Partner), whether they lived with somebody (1 = Yes; 2 = No) and their employment status (1 = Employed; 2 = Unemployed; 3 = Retired). The following were compiled as psychosocial variables: the existence of vulnerability, whereby for this purpose, vulnerability is defined as any characteristic that creates a state of helplessness in the victim against his or her aggressor, a diagnosed mental disorder (the presence of mental disorder was only marked when there was an official diagnosis or clear manifestations of the environment that allowed inferring the existence of the mental disorder), or a pattern of addiction to drugs or alcohol (codified 1 = Yes; 2 = No). And lastly, the criminal records were codified in four dichotomous variables: the existence of a criminal record in general and the existence of past crimes against property, against public health and against people (all codified 1 = Yes; 2 = No). The relationship between victim and perpetrator was also recorded (1 = Partner/ex-partner; 2 = Family member; 3 = acquaintance; 4 = Stranger) and in the cases of family members, the kinship was specified (1 = Son/daughter; 2 = Father/mother; 3 = Other family members). In the case of the perpetrators, the presence of suicide following the act was also recorded (1 = Yes; 2 = No).

Variables of the Incident

In terms of the temporal distribution of the incident, the investigation included the point in the week (1 = weekday; 2 = weekend), and the time of day (1 = Morning; 2 = Afternoon; 3 = Night). With regard to the realisation of the act, the presence of witnesses was recorded (1 = Yes; 2 = No), as was the place in which the events took place and the place in which the body was found (both codified 1 = open space/open air; 2 = closed; 3 = residence), whether the place of discovery was different to that of the event (1 = Same place; 2 = Different place) and the number of victims (1 = One victim; 2 = Multiple victims). With regard to the criminal activity, the recorded data included the weapon used (1 = Bladed weapon; 2 = Firearm; 3 = Blunt object; 4 = Asphyxia; 5 = Others) and the nature of the weapon (1 = Opportunity; 2 = Carried). Lastly, regarding the behaviour prior to the homicide, it was recorded whether the perpetrator inflicted prior injuries to the victim or concealed his or her identity towards the victim, and regarding the behaviour after the fact, the data included whether the perpetrator altered the scene or the body, fled from the scene of the crime, and whether or not the perpetrator turned themselves in or confessed (all codified 1 = Yes; 2 = No).

Results

Characteristics of the Victims

When observing Table 1, the gender of the victims was significantly different between the groups, with women mainly killing men, and men mainly killing women. Nevertheless, the age of the victims did not differ substantially when analysed quantitatively, but when analysing whether the victims were minors, results showed that minors more frequently die at the hands of women. Significant differences also emerged with regard to the employment situation of the victims, revealing that the victims of women are generally not employed.

In terms of the psychosocial characteristics, the victims of women tend to present some kind of vulnerability or mental disorder. Of the 6 victims of female perpetrators, 2 presented age-related degenerative disorders, 1 mood disorder and 1 psychotic disorder; in the other 2 cases, the specific disorder was not known. In the case of the men’s victims, 7 presented degenerative disorders, 2 mood disorders and the remaining 8 were not known.. No differences were found in the presence of addictions. And regarding the existence of a criminal record, no substantial differences were found. Women primarily kill family members outside of the scope of their intimate relationship, and upon exclusively analysing the cases that occur within the scope of the family, it was found that women are more likely to kill sons/daughters, whilst men are more likely to kill partners/ex-partners.

Characteristics of the Perpetrators

With regard to the socio-demographic characteristics of the female perpetrators (see Table 2), no differences were found in terms of age when analysed as a quantitative variable nor in dichotomised form, with not a single recorded case of underage perpetrators. But the results did show that women tend to have a partner at the time of the events, and moreover, they tend to be living with somebody. However, the employment situation did not reveal significant differences.

With respect to the psychosocial variables, women tend to exhibit mental illness to a greater degree than men. Of the 13 female perpetrators with mental disorders, 7 exhibited mood disorders, 2 exhibited personality disorders and 1 psychotic disorder, with the specific disorder unknown in 3 cases. Of the 38 men, 15 exhibited psychotic disorders, 9 mood disorders, 3 personality disorders, 2 degenerative disorders and 9 cases in which the disorder was unknown. No differences were found in the presence of addictions. Where differences were indeed found is in the area of prior criminal records; here, the existence of records in general, and specifically records of crimes against property and against people, are more common amongst male murderers. Finally, the variable of suicide following the act did not reveal any differences in terms of the gender of the perpetrator.

Characteristics of the Events

As can be observed in Table 3, the homicides committed by women mainly took place in the afternoon, with no differences found as far as the day of the week. There are usually no witnesses present, and these homicides mainly play out in homes, although the place of discovery did not show significant differences, nor did the factor of whether the places of the event and of the discovery were the same.

In terms of criminal activity, it was found that women use asphyxiation, and men use firearms. What is more, the weapons used by the women were already present at the scene of the crime. Last but not least, with regard to the behaviours of the perpetrator prior to the homicide, neither the existence of prior injuries nor the concealment of identity were significantly associated with either of the two groups; however, the behaviours after the event did present significant differences: alteration of the scene was associated with women, and it was common for women to remain at the scene following the events. The other behaviours after the occurrence of the crime did not present significant differences.

Multivariate Analysis

Once the variables that showed significant bivariate differences were identified, a binary logistic regression analysis was carried out. For this purpose, only the variables pertaining to the victim and the event that can be determined during the initial moments of the investigation were selected, such that they may be able to help police agents identify whether the perpetrator of the crime is more likely to be a man or a woman. The variables of the victim included the following: gender, whether or not he or she was a minor, and the existence of mental illness. The variables of the event included: the time frame, the type of place in which the event occurred, the weapon used and its nature, and the alteration of the scene.

To avoid collinearity in the dummy variables, the reference categories used were those that demonstrated a greater presence in the data set. The assessment of collinearity did not show multicollinearity between the independent variables, since the minimum tolerance of these variables was 0.761 and the maximum variance inflation factor (VIF) was 1.314. Applying the Wald method of backward variable selection, a total of 13 independent variables were evaluated, including the dummy variables. Of the 9 variables that remained in the final model, 8 showed statistical significance. As can be seen in Table 4, the homicides by women involved victims who were male (1), minors (2) and who had a mental disorder (3). Regarding the act, these women tend to commit homicides in the afternoon (4) and in homes (5). Neither firearms (6) nor blunt objects (7) are commonly used to take the life of the victim.

Discussion

The present study has established a comparison of the homicides committed by women and those committed by men within the domain of the Civil Guard between the years 2013 and 2018. The analysis of the characteristics of the victims, the perpetrators and the criminal activity has shown that there are significant differences between these homicides depending on the gender of the perpetrator. These results are important for the academic field, as they enable a deeper insight into the role played by women in serious crime, specifically in homicide; but they are also of importance for the area of police operation, since as we have seen, it is possible to associate the information available at the crime scene with certain characteristics of the perpetrators, in this case, their gender.

First, it must be pointed out that in keeping with findings from previous studies, the female perpetrators made up 9.8% of the total of analysed perpetrators, with 3 out of every 4 homicides committed by women taking place in the family setting, and the cases of filicide standing out above all. Statistically significant differences were found in the gender of the victim, since women predominantly kill men, whilst men predominantly kill women, a result that coincides with the findings of the study by Sea et al. (2017). Whilst there are no differences in the ages of the victims, in line with the findings by Häkkänen-Nyholm et al. (2009) and Sea et al. (2017), underage victims were indeed found to be associated with the homicides committed by women, which emphasises the involvement of women in cases of filicide (Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009; Moen et al., 2016; Nagata et al., 2016; Trägårdh et al., 2016), nor are there any differences in the ages of the victims and the perpetrators based on the gender of the latter, since although the difference in age in the cases of filicide is very large, these cases are compensated by others in which the victims are older than the perpetrators, such as in cases of parricide or matricide. The number of women who kill other women is relatively low, both when compared to male victims of female perpetrators and female victims of male perpetrators. These findings show that, in those cases in which the victim is a young male, it is more likely that homicide is committed by a woman. Furthermore, no differences were found in the origin of the victims, nor their marital status, nor whether they lived with someone at the time of the events, although at the descriptive level, the victims of the women tend to be Spanish, are not in a relationship at the time of the events and live with other people. In contrast to the study by Sea et al. (2017), the results of this study show that the victims of women are not usually employed, which may be due, in part, to the fact that many of the victims of women are their children, who are not old enough to be working or even studying. Looking at the psychosocial profile, women kill victims who can be considered vulnerable, either because they are of a young age, as has already been established, or due to the fact that these victims tend to exhibit some kind of mental illness to a greater extent than the victims of men. Lastly, it should be noted that neither the variable of addictions nor the prior criminal records showed significant differences, which may be due, in part, as in the employment status, to the fact that many of the victims of women are minors who are not old enough to have prior criminal records.

When it comes to the profile of the perpetrators, although the women are generally older than the men (43 vs. 40 years respectively), these differences are not great enough to be significant; consequently, the results from this study support the findings from the investigations by Häkkänen-Nyholm et al. (2009), Nagata et al. (2016) and Sea et al. (2017). As mentioned in the introduction, it is important to emphasise the fact that the age will be influenced by the context of the homicide and by the existing relationship between victim and perpetrator, as for example, in cases of filicide, the women will be younger than when they kill their partners (Moen et al., 2016). With regard to age, it is important to point out that no underage perpetrators were recorded, which can again be explained by the involvement of women in homicides of their children and partners, making it more likely that in these cases, the women are older than in homicides that involve strangers and that occur in the context of a brawl or interpersonal dispute, with these types of cases being more common amongst male perpetrators. Unlike the findings from some studies (Moen et al., 2016; similar to the study by Trägårdh et al., 2016; Yourstone et al., 2008), no significant differences were found in the origin of the perpetrators, although at the descriptive level, the female perpetrators tend to be of Spanish nationality. In addition, they also tend to have a partner at the time of the event and they tend to be living with somebody, findings that coincide with the results from previous studies (Flynn et al., 2011; Sea et al., 2017; Trägårdh et al., 2016). Although some research has found that men tend to be unemployed in contrast to women (Flynn et al., 2011; Putkonen et al., 2011; Sea et al., 2017), the present study did not find any differences in the employment situation based on the gender of the perpetrators. An important finding, and one that confirms the conclusions from other investigations (Flynn et al., 2011; Nagata et al., 2016; Putkonen et al., 2011; Trägårdh et al., 2016), is that, to a greater degree than men, women tend to exhibit mental disorders at the time of the incident. Although studies show that it is more common for men to be under the influence of substances at the time of the event (Eckhardt & Pridemore, 2009; Moen et al., 2016), no significant differences were found. As far as prior criminal records, the literature has found that women do not tend to have a record (Flynn et al., 2011; Putkonen et al., 2011; Sea et al., 2017; Trägårdh et al., 2016), and this idea is upheld up by the results of the study. Finally, examining the factor of suicide after the incident, the results confirm the findings by Trägårdh et al. (2016), namely that there are no differences based on the gender of the perpetrator.

The temporal distribution of homicides based on the gender of the perpetrator has not been addressed by previous studies, and in this sense, the present investigation shows that, although there are no differences as far as the day of the week, when analysing the time frame, it was found that the homicides committed by women more commonly take place during the afternoon. Homicides perpetrated by women are not usually carried out in the presence of witnesses, owing to the fact that they mainly take place in residences, whilst men kill in open spaces, making the presence of witnesses more likely in the latter cases. Upon examining the displacement of the body, it was found that although there are no significant differences, in homicides committed by women, the body of the victim tends to appear in a scene different to that in which the act was carried out (23.2 vs. 14%), coinciding with the findings from the study by Häkkänen-Nyholm et al. (2009) in which displacement of the body was associated with cases involving women. This displacement can be explained, in part, by two reasons: (a) since the majority of women’s victims are family members, the women may opt to displace the body as a method of disassociation from the homicide in an attempt to hinder the investigation; and (b) because, as underage victims are associated with women, the body of these victims may be easier to displace than in cases in which the victims are older. No differences were found in the number of victims; the existence of multiple victims was a very unusual circumstance in the study sample, since a mere 5% of the total number of homicides recorded more than one victim. Although studies differ when it comes to the type of weapon associated with women and men, it seems that there is a consensus that firearms are primarily used by men and asphyxiation methods by women (Fox & Fridel, 2017; Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009; Moen et al., 2016), and these results were also confirmed by the present study, noting that of the 100 cases in which firearms were used, only 1 involved a female perpetrator. The results regarding the nature of the weapon are similar to those obtained by Sea et al. (2017), namely that women tend to kill with weapons of opportunity. With regard to the criminal behaviours prior to the homicide, no differences were found in the presence of prior injuries, nor as to whether or not the perpetrator conceals his or her identity. On the other hand, although the study by Häkkänen-Nyholm et al. (2009) found that women exhibited more alterations to the body, the results of this study showed that there are no differences in terms of the alteration to the body, whilst there are in fact differences in the alteration of the scene. And last but not least, in terms of the subsequent behaviours of the perpetrators, studies have found that women remain at the scene and tend to confess to the homicide more than men (Häkkänen-Nyholm et al., 2009); this study partially supports these results, inasmuch as the women in the sample tend to remain at the scene, but they do not turn themselves in or confess to the crime more than the men.

Limitations and Future Areas of Research

This investigation presents strengths and limitations. Firstly, it should be noted that this study examined all of the cases of homicide that were resolved in the domain of the Civil Guard in the period of study, which makes it possible to extrapolate these findings to homicides recorded in other years in this same domain, but does not mean that they can be extrapolated to all of Spain. Future investigations, therefore, should analyse cases across the entire national territory to see whether these patterns relating to the gender of the perpetrator remain stable. A further strength of this study is that, whilst almost all of the analysed variables are supported by an existing theoretical foundation, it also includes other variables that have enabled a more in-depth examination of the victim profiles and, above all, the criminal behaviour. The access to this type of information was possible thanks to the origin of said information: as it was police information, the criminal activity is more detailed than it is when dealing with studies that take a more clinical approach. Finally, the aim was to establish an initial picture of the homicides committed by women by comparing these homicides with those committed by men, which is why the inclusion of all types of homicides, regardless of the type of prior relationship between victim and perpetrator, and without focusing the attention on the perpetrators who exhibited some kind of distinctive characteristic, enabled a clearer general overview of these cases.

All in all, this study provides a good foundation upon which to continue investigating the differences in homicides depending on the gender of the perpetrators. For example, it has been shown that women mainly commit homicides within the scope of the family, but are there differences between the family homicides committed by women and men? With this in mind, it is proposed that specific types of homicide are analysed, such as the study by Liem and Koenraadt (2008) that analyses the differences based on gender in cases of filicide, or the study by Caman et al. (2016) that focuses on analysing these differences in cases of intimate partner homicide. Other studies could also focus on analysing more specific issues, such as the differences in homicides committed by men and women based on the age of the victims.

Conclusions

Despite the fact that the number of female murderers is low, in comparison with the men, it appears that the homicides committed by women present a pattern that, broadly speaking, is standard throughout the various countries of the world in which these cases have been analysed. The first conclusion obtained both from this study as well as from a revision of the literature on this topic is that the homicides committed by women are homicides involving family members. This fact has an impact on the characteristics of the victims and of the perpetrators themselves, in addition to the characteristics of the event, profiling the victims of women as vulnerable, due to their young age as much as to the possible presence of some kind of mental disorder. Furthermore, the characteristics of female killers also depict a more normalised and integrated profile, since they tend to have a partner and be living with somebody at the time of the events, and the presence of a mental illness can lead them to make an attempt on the life of those closest to them (children or partners). This less antisocial profile is also reflected in the absence of addictions and prior criminal records, which again distances women from homicides related to criminal activities, in which the homicide may occur as a consequence of having committed some other criminal offence, or in which the homicide itself is considered as a crime that makes it possible to commit a further crime. The contextual characteristics and the criminal behaviours are also influenced by the setting in which women generally kill; to be specific, these homicides occur in residences and using asphyxiation, which is a method that the literature has linked with filicide.

In general, the results obtained in other studies were corroborated, albeit with some particularities that have already been discussed above. It seems clear that there are differences between the homicides committed by women and those committed by men, and it has been made apparent that the relationship between victim and perpetrator is of particular importance since, as previously contended, this will influence the rest of the variables surrounding the homicide. But what is the use of understanding these differences? As explained in the introduction, when it comes to creating typologies that help to understand the phenomenon of homicide, as well as creating intervention programmes for the aggressors, studies have only examined the masculine population without paying much attention to the cases of women, which impedes these results and programmes, and even the explanatory models, from being applicable to female perpetrators. Therefore, these results are proof that the criminality of women is different to that of men when it comes to the phenomenon of homicide, and this fact should be taken into consideration when explaining the phenomenon itself just as much as when developing suitable criminal policies for the reduction and prevention of this phenomenon. Just as Kim et al. (2017) pointed out, in order to intervene in an effective manner, it is necessary to create specific strategies based on the scientific evidence, given that the general interventions did not affect the various subtypes of homicides. If the findings show that women mainly kill their children or people with some type of vulnerability, the necessary action to take would be to examine the causes more closely and base the prevention strategies on the specific characteristics of the case. Another important area, and one that this study aimed to explore by using only variables that can be determined by the police investigators in the first moments of an investigation, is the importance that these studies can have for practical police work. The present study analysed the link between a range of variables related to the scene of the crime and the gender of the perpetrator, which made it possible to identify what type of homicide is more likely to be associated with female perpetrators of homicide. But this is just one of the different variables that can be of police interest; there is still a necessity to develop studies that include the analysis of other dependent variables such as the existence of prior criminal records or the existence of a previous relationship between victim and perpetrator. This type of information can be taken into account by police investigators when dealing with new cases of homicide, which will facilitate the management of police resources.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Change history

22 November 2021

Springer Nature’s version of this paper was updated to reflect the Funding information: Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

References

Beatton, T., Kidd, M. P., & Machin, S. (2018). Gender crime convergence over twenty years: Evidence from Australia. European Economic Review, 109, 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2018.01.001

Belknap, J., Larson, D. L., Abrams, M. L., Garcia, C., & Anderson-Block, K. (2012). Types of intimate partner homicides committed by women: Self-defense, proxy/retaliation, and sexual proprietariness. Homicide Studies, 16(4), 359–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767912461444

Braga, A., & Dusseault, D. (2018). Can homicide detectives improve homicide clearance rates? Crime & Delinquency, 64(3), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128716679164

Caman, S., Howner, K., Kristiansson, M., & Sturup, J. (2016). Differentiating male and female intimate partner homicide perpetrators: A study of social, criminological and clinical factors. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 15(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2015.1134723

Carabellese, F., Felthous, A. R., Mandarelli, G., Montalbò, D., La Tegola, D., Parmigiani, G., Rossetto, I., Franconi, F., Ferretti, F., Carabellese, F., & Catanesi, R. (2020). Women and men who committed murder: male/female psychopathic homicides. Journal of forensic sciences. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.14450

Cooper, A., & Smith, E. (2011). Homicide trends in the United States, 1980–2008. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/htus8008.pdf

Côté, S. M. (2007). Sex differences in physical and indirect aggression: A developmental perspective. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 13, 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-007-9046-3

de Vogel, V., & de Spa, E. (2019). Gender differences in violent offending: Results from a multicentre comparison study in Dutch forensic psychiatry. Psychology, Crime & Law, 25(7), 739–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2018.1556267

Eckhardt, K., & Pridemore, W. A. (2009). Differences in female and male involvement in lethal violence in Russia. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2008.12.009

Eriksson, L., McPhedran, S., Caman, S., Mazerolle, P., Wortley, R., & Johnson, H. (2018). Criminal careers among female perpetrators of family and nonfamily homicide in Australia. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518760007

Flynn, S., Abel, K. M., While, D., Mehta, H., & Shaw, J. (2011). Mental illness, gender and homicide: A population-based descriptive study. Psychiatry Research, 185(3), 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.040

Fox, J. A., & Fridel, E. E. (2017). Gender differences in patterns and trends in U.S. homicide, 1976–2015. Violence and Gender, 4(2), 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2017.0016

González, J., Sánchez, F., López-Ossorio, J., Santos, J., & Cereceda, J. (2018). Informe sobre el homicidio. España 2010–2012. Madrid, Spain: Ministerio del Interior. Retrieved from: http://www.interior.gob.es/documents/642317/1203227/Informe_sobre_el_homicidio_España_2010-2012_web_126180931.pdf/9c01b8da-d1b8-42b9-9ab0-2cf2c3799fb1

Häkkänen-Nyholm, H., Repo-Tiihonen, E., Lindberg, N., Salenius, S., & Weizmann-Henelius, G. (2009). Finnish sexual homicides: Offence and offender characteristics. Forensic Science International, 188(1–3), 125–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.03.030

Jackson, R. D., & Motley, S. M. (2019). Offending, gender, race, and ethnicity. The Encyclopedia of Women and Crime. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118929803.ewac0380

Kim, B., Gerber, J., Kim, Y., & Hassett, M. R. (2017). Female-perpetrated homicide in South Korea: A homicide typology. Deviant Behavior, 39(8), 1042–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2017.1395671

Liem, M., & Koenraadt, F. (2008). Filicide: A comparative study of maternal versus paternal child homicide. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 18(3), 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.695

Liem, M., & Pridemore, W. (2014). Homicide in Europe. European Journal of Criminology, 11(5), 527–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370814540077

Linde, A. (2019). Female homicide victimization in Spain from 1910 to 2014: The price of equality? European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-019-09427-1

Moen, E., Nygren, L., & Edin, K. (2016). Volatile and violent relationships among women sentenced for homicide in Sweden between 1986 and 2005. Victims & Offenders, 11(3), 373–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2015.1010696

Nagata, T., Nakagawa, A., Matsumoto, S., Shiina, A., Iyo, M., Hirabayashi, N., & Igarashi, Y. (2016). Characteristics of female mentally disordered offenders culpable under the new legislation in Japan: A gender comparison study. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 26(1), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.1949

National Statistics Institute [INE]. (2019). Cifras de población (información detallada) población residente por fecha, sexo y edad. Retrieved July, 27, 2020, from: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=10262

Pizarro, J. M., DeJong, C., & McGarrell, E. F. (2010). An examination of the covariates of female homicide victimization and offending. Feminist Criminology, 5(1), 51–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085109354044

Pizarro, J. M., Zgoba, K., & Jennings, W. (2011). Assessing the interaction between offender and victim criminal lifestyles & homicide type. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(5), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.05.002

Putkonen, H., Weizmann-Henelius, G., Lindberg, N., Rovamo, T., & Häkkänen-nyholm, H. (2011). Gender differences in homicide offenders’ criminal career, substance abuse and mental health care. A nationwide register-based study of Finnish homicide offenders 1995–2004. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.782

Santos, J., González, J. L., & Touza, J. M. (2019). Homicidio en demarcación de la guardia civil. El uso de los datos en la investigación criminal. Cuadernos de la Guardia Civil, 59, 177–197.

Sea, J., Youngs, D., & Tkazky, S. (2017). Sex Difference in homicide: Comparing male and female violent crimes in Korea. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(11), 3408–3435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X17740555

Suonpää, K., & Savolainen, J. (2019). When a woman kills her man: Gender and victim precipitation in homicide. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(11), 2398–2413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519834987

Trägårdh, K., Nilsson, T., Granath, S., & Sturup, J. (2016). A time trend study of swedish male and female homicide offenders from 1990 to 2010. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 15(2), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2016.1152615

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2019). Global study on homicide. Retrieved from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/global-study-on-homicide.html

van der Heijden, M., & Pluskota, M. (2018). Introduction to crime and gender in history. Journal of Social History, 51(4), 661–671. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsh/shx144

Wang, J., Zhang, S., Zhong, S., Mellsop, G., Guo, H., Li, Q., Zhou, J., & Wang, X. (2019). Gender differences among homicide offenders with schizophrenia in Hunan Province, China. Psychiatry Research, 271, 124–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.039

Yourstone, J., Lindholm, T., & Kristiansson, M. (2008). Women who kill: A comparison of the psychosocial background of female and male perpetrators. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 31(4), 374–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2008.06.005

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Jorge Santos Hermoso.

Methodology: Jorge Santos Hermoso.

Formal analysis and investigation: Jorge Santos Hermoso.

Writing—original draft preparation: Jorge Santos Hermoso.

Writing—review and editing: Jorge Santos Hermoso; José Manuel Quintana-Touza; Zaida Medina-Bueno; María Regina Gómez-Colino.

Resources: José Manuel Quintana-Touza; Zaida Medina-Bueno; María Regina Gómez-Colino.

Supervision: José Manuel Quintana Touza.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Santos-Hermoso, J., Quintana-Touza, J.M., Medina-Bueno, Z. et al. Does She Kill Like He Kills? Comparison of Homicides Committed by Women with Homicides Committed by Men in Spain. Eur J Crim Policy Res 29, 167–189 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-021-09492-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-021-09492-5