Abstract

The judgments of criminal appeal courts are an example of Calabresi and Bobbitt’s concept of ‘tragic choice’. Judges justify convictions by reference to the values which they attribute to criminal procedures: fairness, truth and rights, rather than the full range of considerations which have influenced the introduction of those procedures: cost, efficiency, crime control, public perceptions of crime, etc. The difficulties facing the Court of Appeal in justifying convictions by juries after a full trial are multiplied in the case of convictions following guilty pleas. A procedure which on its face is less capable of identifying guilt than a trial, has to be defended on the basis that it is overwhelmingly more capable of identifying guilt (or so fair as to justify disregarding the possibility of innocence). Recent changes to the plea system restricting maximum sentence discounts to pleas made at the earliest opportunity further distance guilty pleas from the protections afforded by trial, and compound the difficulties in justifying these convictions as ‘safe’. With guilty pleas we have reached a situation where the Court of Appeal seems unable to provide a remedy for miscarriages, but instead, like the judges of the 19th century opposing the creation of the Criminal Court of Appeal, claims the procedure is so safe that there is little or no need for review, even in cases of procedural irregularity (short of abuse of process) or new evidence (short of exoneration).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

I think that the Complaints of the present Mode of administering the Criminal Law have little Foundation, for the Cases in which the Innocent are improperly convicted are extremely rare; some, no doubt, there are; and I consider it impossible in any human System in administering Justice to avoid such Misfortunes occasionally. (Baron Parke’s evidence in 1848 to a Select Committee of the House of Lords on a Criminal Law Administration Amendment Bill).Footnote 1

Is Baron Parke’s sanguinity about the improbability of miscarriages of justice in the 19th century merely a matter of historical interest, or does it find echoes in judicial attitudes towards the safety of convictions today? And if such echoes exist, does this point to the presence, in our criminal justice system, of factors that transcend historical change? In this article we explore the theme of judicial reluctance towards undoing convictions in the context of the ever-increasing reliance on guilty pleas as a mechanism by which those convictions are achieved.

Overview

Our exploration proceeds through four stages. In Part One we draw on arguments, previously made by us and mirrored in the writings of many others, as to the reasons why appeal court judges necessarily show deference to the trial court practices which they formally supervise, and the difficulties which this creates for them when it comes to identifying miscarriages of justice. In the second part, we describe the English criminal justice system’s current dependence on convictions obtained through guilty pleas, and the constraints placed on the possibilities to appeal those convictions. In the third part, we consider the justifications given for these restricted rights of appeal and demonstrate that they lack both plausibility and coherence. They are, we will claim, modern examples of what, from an external perspective appear as a wilful refusal to embrace the real chances for miscarriages of justice to arise from flawed criminal justice procedures. In the last section, we discuss the prospects for changes which might alleviate the need for our senior judiciary to continue to deny the obvious risk of wrongful (both in the sense of unfair and factually incorrect) convictions when considering appeals from convictions obtained following guilty pleas.

Part One: The Need for Appeal Courts to Exhibit Deference Towards the Procedures which They Supervise

The reluctance of the English judiciary to re-examine convictions arising from trial by jury has a long history, dating back to well before the passing of the Criminal Appeal Act 1907 and the creation of the Criminal Court of Appeal, the first court to be given this specific authority.Footnote 2 Whilst there are many factors which have led and may well continue to lead to this reluctance, whether directed towards jury trial or other means by which convictions are achieved, one of the central reasons is common to any system of appeals – the need for a workable relationship between institutions making decisions at first instance, and the bodies that have authority for correcting their errors.Footnote 3 In the context of criminal appeals, the Court of Appeal has to be able to identify errors within the criminal justice system, without undermining the ability of first instance criminal courts to administer the number of cases that are being steered towards them through arrests, charges and other pre-trial procedures. As part of this task, it needs to avoid overwhelming itself by generating more appeals than it, or other courts acting in their capacity as appeal courts, can hope to process or can only process with an ever-increasing backlog of undecided cases.

A workable relationship between the appeal and trial courts has implications for what the appeal courts can identify as errors. For example, if an appeal court treats every case where it would reach a different verdict on the evidence as an error, then there does not need to be anything wrong with trial procedures for an appeal to be possible: all verdicts are open to a de novo consideration. Since its creation, the Criminal Court of Appeal (now Court of Appeal (Criminal Division)) has strongly resisted such a role,Footnote 4 limiting itself to the review of procedures pre-trial and trial, and adamantly (subject to its interpretation of a few so-called ‘lurking doubt’Footnote 5 or otherwise exceptional cases) only reappraising verdicts where it finds procedural errors or compelling new evidence. This resistance has been the subject of strong criticism, with the Court of Appeal regularly, throughout its history, accused of showing ‘undue deference’ to the verdicts of juries.Footnote 6 There is a substantial academic literature dealing with this aspect of the Court’s performance, and with the work of the Criminal Cases Review Commission (‘CCRC’), the body introduced to redress a variety of perceived failures, including that of the Court of Appeal as a mechanism for the rectification of miscarriages of justice.Footnote 7 But despite whatever may constitute ‘undue’ deference, there is an inescapable need for the Court of Appeal to show some level of deference towards the bodies and procedures which it supervises.

As the body (together with other bodies sitting as lower appeal courts) which decides on which convictions should be quashed, the Court of Appeal also has responsibility for deciding on the converse – which convictions should stand. This unavoidably involves an exercise in justification. Every rejected appeal or application for leave to appeal is a decision involving the claim that the procedures that led to the conviction were ‘good’ or at least ‘good enough’. So, for example, whilst there are any number of ways in which a trial before a jury may go wrong, it is not open to the Court of Appeal to express doubts on the ability of jury trial, as an institution, to reach correct conclusions as to the guilt of those that they convict. The ‘good enough’ quality of the jury as a fact-finding body is not an opinion reached on the basis of social scientific evidence,Footnote 8 it is something reiterated, within the criminal justice system, explicitly or implicitly, with each rejected appeal against a jury verdict. Not only must the Court acknowledge the general suitability of juries as fact-finding bodies, it must also resist grounds of appeal which would undermine the ability of juries to execute their fact-finding function. So, for example, ‘normally’ allowing appeals on the basis of evidence not used, or arguments not made, would seriously weaken the ability of juries to determine guilt, as every trial involves some unused evidence and some discarded arguments.Footnote 9

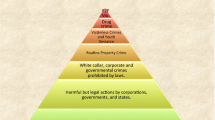

The statutory powers allocated to the Court of Appeal give the Court an almost unlimited power to declare any conviction unsafe.Footnote 10 This formally unlimited supervisory power has to be seen in the context of a system whose features lie largely outside of the Court’s control. It does not, for example, establish the levels of legal aid, or the funding available to the police or the Crown Prosecution Service (‘CPS’) for the investigation and prosecution of crime, or even the budgets allocated to itself or the courts which it supervises. And whilst much criminal procedure is within judicial control, being either a creature of the common law, or rules announced by the Court itself, or by bodies staffed by judges,Footnote 11 substantial elements are the result of statute and policy priorities, over which judges have limited influence.Footnote 12 The criminal justice system is constructed in response to considerations of cost and efficiency, as well as more obvious political agendas such as social control, and many other indeterminable factors, such as the perceived need to respond to fears of crime expressed within the mass media.Footnote 13 But, when attempting to justify convictions as ‘safe’ it is not open to the Court of Appeal to draw on these kinds of consideration in deciding that particular defendants, who may be innocent of the crimes of which they are charged, should nevertheless continue to be punished. The Court operates through a discourse which assumes that convictions obtained in accordance with defendants’ rights will ordinarily establish ‘safe’ convictions in nearly all cases, limiting itself to quashing convictions obtained where there has been a breach of those rights, or where new evidence has emerged that was not available at the trial, and only exceptionally in other ‘lurking doubt’ cases. The need to assume that the criminal justice process ordinarily produces safe convictions means that the Court of Appeal’s supervisory role involves a strong element of deference. In previous publications we have described the Court of Appeal’s need to justify a system of trial constructed by reference to factors outside its control and for reasons that it cannot articulate, as an example of tragic choice.Footnote 14 Choices are tragic here arising from the difficulties of upholding values associated with justice – the ability of the criminal process to establish the fact of defendants’ guilt through fair procedures – in the face of institutions whose design is heavily influenced by other values such as cost and efficiency.

Part Two: The Guilty Plea Regime and Restrictions on the Ability to Appeal

The need for deference, and the difficulties of justifying it, are heightened when one refocuses to consider the relationship between the Court of Appeal and convictions achieved through guilty pleas. At present, around 91% of the convictions obtained by the CPS are the result of guilty pleas. The figure for convictions obtained via plea in the Crown Court alone is 88.38%.Footnote 15 Thus, we have a large dependence on guilty pleas comparable to that in the USA, a level which led their Supreme Court to observe that pleas, not trials ‘is the criminal justice system’.Footnote 16 As in the United States, defendants are offered inducements to plead guilty, in the form of lower sentences than would occur if they were convicted at trial. These reductions occur in three ways: through an automatic reduction of up to a third off the sentence that would be the appropriate starting point if conviction had followed trial; through the prosecution accepting a guilty plea to a lesser charge and not pursuing the more serious charge or charges;Footnote 17 by the prosecution agreeing to the conviction being based on a less serious version of the facts than might otherwise be established at trial.Footnote 18 Contrary to former orthodoxy,Footnote 19 our judiciary can now confirm, on request, what sentence would be imposed if the defendant pleaded guilty and, in a break from the adversarial tradition, may even raise the issue of a guilty plea in open court where it appears clear to them that a guilty plea should have been considered by the defendant.Footnote 20 They may not however inform defendants of the sentences that they can expect if they continue to plead not guilty and are convicted at trial.Footnote 21 The scope and need for circuit judges to become directly involved in this process has been reduced by the recent standardisation of reduction of sentence attributable to the plea itself, and by the introduction of a requirement that the maximum one third sentence reduction will only occur if defendants plead guilty at their first appearance at the Magistrates’ Court.Footnote 22 The former reduces the need for individual judges to form their own views of what reduction might be justified (for example, giving less reduction where they consider the evidence of guilt overwhelming);Footnote 23 the latter requires defendants who wish to obtain maximum reductions of sentence to make their pleas prior to the case appearing at the Crown Court. Unless defendants enter a guilty plea at this first appearance the reduction for guilty plea reduces from a third to a quarter (with further staged reductions down to one tenth of sentence where the guilty plea is entered on the first day of trial).

There has been a recent regularisation of the information that must be disclosed to defendants at this early stage.Footnote 24 Whilst this has a number of purposes,Footnote 25 one of these is to ensure that the CPS can demonstrate to defendants the strength of the prosecution case. Without this, the incentive provided by the maximum discount for pleading guilty would be undermined in failing to demonstrate to defendants that they face a strong likelihood of being convicted at trial. The level of disclosure required at this stage depends on whether defendants are in custody, and whether prosecutors can anticipate a guilty plea at the first hearing. The lowest level of disclosure applies to defendants in custody. Here disclosure is limited to a summary of the circumstances of the offence and defendants’ criminal record.Footnote 26 But if the prosecution intends to put any other material before the court, this must first be disclosed and defendants given time to consider it prior to the decision to plead.Footnote 27 The next level of advance disclosure applies to those not in custody, where the prosecution expects defendants to plead guilty. Here, prior to the first hearing at the Magistrates’ Court, the CPS are required to provide the court and defendantsFootnote 28 with: a summary of the circumstances of the case; any account given by the defendant in interview; any written witness statement or exhibit that the prosecutor then has available and considers material to plea or to the allocation of the case for trial or sentence; a list of the defendants’ criminal record, if any; any available victim impact statement.Footnote 29 The highest level of advance disclosure is reserved for defendants not in custody, who are expected to plead not guilty.Footnote 30 The additional disclosure required here is not directed at the plea decision (though it may affect this), but is intended to allow the issues at trial to be identified.Footnote 31 The additional required information consists of details of witnesses’ availability, as far as they are known; an indication of any medical or other expert evidence that the prosecution is likely to adduce in relation to a victim or the defendant; any information as to special measures, bad character or hearsay, where applicable.Footnote 32 Certain kinds of exhibit evidence are also expressly required by this stage if forming part of the prosecution case – CCTV and streamlined forensic reports. Note however that any failure to produce this last level of advance disclosure does not affect the requirement that the defendant should enter a plea at the first hearing.Footnote 33

Underlying this early plea system, and the disclosure requirements that accompany it, is the assumption that decisions to plead guilty can be made on the basis of the prosecution case, as it has been developed up to this point, without any opportunity to develop the defence case. In particular, defendants have no right to inspect the material obtained by the police which does not form part of the prosecutions’ case. The defence has to rely on prosecutors’ duty to disclose any material which might undermine the prosecution case,Footnote 34 as the defence have no statutory right to disclosure of unused material unless and until a not guilty plea is entered. There is a further assumption that this assessment can be made swiftly, as the latest date for service of the prosecution case is the morning of the day of the first hearing.Footnote 35

The number of cases disposed of via guilty pleas has implications for workloads, of the Court of Appeal, if such cases are appealed from the Crown Court, and for Crown Courts when appealed from Magistrates’ Courts, and if successful appeals would result in an order for a retrial. One can see how the Court of Appeal avoids this increased workload through the restrictions which it places on the grounds of appeal, and especially against convictions based on guilty pleas. In nearly all such cases, defendants can only appeal on the basis that their pleas were involuntary or equivocal.Footnote 36 The need for the plea to be unequivocal boils down to a requirement that the plea represents a confession to facts that constitute the offence charged.Footnote 37 So, for example, where a defendant pleads guilty on the basis of alleged facts that do not constitute the offence, an appeal is allowed.Footnote 38 The requirement of voluntariness adds little to this, as the courts require only that the decision to plead guilty must be the defendants’ own acts, and not something that can be decided for them by their legal representatives. A plea is not rendered involuntary because defendants may have felt coerced by the greater sentence that would follow if convicted at trial.Footnote 39 Indeed, if this were sufficient to render a plea involuntary, then all guilty plea convictions would be appealable. Nor does it make a difference if the pressure arises from an offer of a lower sentence or of a decision not to prosecute a family member, should defendants plead guilty.Footnote 40 This too is considered by the Court of Appeal to be a ‘normal’ situation.Footnote 41 The restricted meanings of what constitutes equivocation and voluntariness limit the legal advice required for a valid guilty plea. Defendants must understand what facts they are admitting to, and their intended factual admission must constitute the offence.Footnote 42 But there is no need for defendants to have an accurate view of the likelihood that they would be convicted if they opted for trial.Footnote 43 The restricted need for advice has in turn allowed for the introduction of the requirement that defendants should plead guilty at the earliest opportunity if they are to enjoy a full (one third) reduction in sentence in return (see description above).Footnote 44

The reluctance to allow appeals against guilty plea convictions is not limited to cases where defendants, without any breach of their rights, may have succumbed to the pressure to plead guilty arising from sentence discounts. The restrictions extend even to cases where defendants have suffered from breaches of their rights, that is cases which, had the convictions resulted from trials, might have led to successful appeals. The standard applied to appeals based on procedural irregularities where defendants have pleaded guilty is closely linked to the standard for a valid plea. So, for example, appeals based on erroneous judicial rulings, and appeals based on incompetent legal advice, can succeed where the effect of the ruling or advice is to lead defendants to believe that the facts they claimed occurred constituted offences when they did not, or to believe that they had no defence to the charge where one was available.Footnote 45 But errors that ‘merely’ weaken defendants’ chances of acquittal are not sufficient. This is because in the former situation, the guilty pleas cannot be read as admission to the crimes, whilst in the latter situation they can, and are. Defendants who plead guilty cannot challenge rulings by trial judges that have weakened their defences, but must plead not guilty and risk the higher sentence that will follow if convicted at trial.Footnote 46 Defendants who plead guilty can still appeal an irregularity that amounts to an ‘abuse of the process’.Footnote 47 This is something that, if discovered prior to conviction, would have resulted in the proceedings being stayed on the basis that a fair trial was no longer possible. This is a high standard so, for example, non-disclosures, however relevant to defendants’ decisions to plead guilty, are unlikely to result in successful appeals in the absence of proof that the non-disclosures were occasioned by dishonesty.Footnote 48

There is also a greater reluctance to allow appeals on the basis of new evidence that throws doubt on defendants’ guilt. The Court of Appeal has stated that this will only exceptionally be allowed in the case of a guilty plea.Footnote 49 With convictions following trial, new evidence needs to be capable of belief, provide a ground of appeal, would have been admissible at the trial and there are cogent reasons for the failure to have obtained or adduced it earlier.Footnote 50 But the approach to new evidence following guilty pleas is much narrower and in practice closer to a requirement of exoneration. For example, where someone else has subsequently been convicted of the same crime, or there is incontrovertible evidence that another person committed that crime.Footnote 51

Part Three: Justifying Guilty Pleas

Justifications Offered for the Introduction and Standardisation of Discounted Sentences for Guilty Pleas

The current system of guilty pleas is not something which was first introduced as a reform in pursuit of a particular policy. Rather, it evolved. In sharp contrast to the current situation judges, for example in the UK in the early 18th century, discouraged guilty pleas,Footnote 52 preferring that a trial (often a short affair, lasting at most a few hours)Footnote 53 take place. A trial enabled both judge and jury to hear defendants’ responses to the evidence against them, and to judge their character, which was relevant to both the decision on their guilt, and the punishment that should follow. The willingness to accept guilty pleas developed in response to the changing nature of trials in the second part of the 18th century. With the increasing involvement of lawyers, trial became more formal, complex, and protracted.Footnote 54 This meant that guilty pleas had an advantage, in terms of saved costs, time, etc. that they had formerly lacked. Whilst some scholars attribute the growth of guilty pleas solely to the desire to avoid the increased costs of this new more expensive form of trial, others have argued that changes in the nature of prosecution are a more important factor.Footnote 55 When the prosecution of crime was left to private parties, and defendants represented themselves, there was little scope for any negotiation over the charge. But with the political acceptance that crime is a government responsibility, and the introduction of state police authorities who both investigate and prosecute crimes, there was both the possibility of negotiated charges and sentences, and a political benefit from achieving them. In the United States, by the middle of the 19th century, plea bargaining had become an important tool in the armoury of public prosecutors with responsibility for tackling crime.Footnote 56 In the United Kingdom, plea bargaining has until recently developed on a more informal basis. There has always been a choice, previously open to the police, now within the control of the CPS, as to which charge to pursue where overlapping charges are possible, and to prefer only the lesser charge in response to a guilty plea (as has commonly occurred with, for example, assault cases). The judiciary’s first contribution to this evolutionary process was their willingness to accept pleas in place of trials, and to treatFootnote 57 guilty pleas as an expression of remorse justifying a reduction of sentence.Footnote 58 But routinely offering sizable sentence discounts for guilty pleas has served to undermine the original ‘remorse’ rationale. Once there is an expectation that pleading guilty will normally lead to a sentence discount, it becomes difficult to distinguish between remorseful guilty defendants and unremorseful guilty defendants who have learned that guilty pleas will be treated as a sign of remorse and earn shorter sentences. More seriously still, significant and routine sentence reductions for guilty pleas raises the obvious risk that at least some of those pleading guilty will be unremorseful innocent defendants who plead guilty solely to reduce the expected sentence. As noted by the Royal Commission on Criminal Justice: ‘… it would be naïve to suppose that innocent persons never plead guilty because of the prospect of the sentence discount’.Footnote 59

More recently, the desire to save costs by encouraging defendants to plead guilty at the earliest opportunity has led to sentencing guidelines that officially separate pleading guilty and expressing remorse into two independent reasons for reducing defendants’ sentences. This separation prevents judges from refusing to offer the standard discount for pleading guilty where they suspect the genuineness of the remorse accompanying the plea (for example, where defendants have insisted on their innocence up to the moment when they have been presented with overwhelming evidence of their guilt). Separating the two reasons for sentence reductions makes the benefits of pleading guilty more certain, and thus increases the effectiveness of standard plea discounts as inducements to plead guilty. But it also serves to undermine further any claim that guilty pleas are remorseful expressions of the truth of defendants’ guilt. The official separation of the guilty plea from remorse as a reason for sentence reduction forms part of a package of reforms (the early plea procedure described above) justified by reference to the public monies saved through reduced trial preparation and investigation, the reduced impact of crimes upon victims, and the benefits to victims and witnesses who then do not have to testify.Footnote 60 All three of these claims are contestable.Footnote 61 However, the more important issue here is whether they increase the pressure on innocent defendants to plead guilty rather than to seek an acquittal at trial. In the introduction to the sentencing guidelines setting out the early guilty plea procedure, it states that: ‘The purpose of this guideline is to encourage those who are going to plead guilty to do so as early in the court process as possible. Nothing in the guideline should be used to put pressure on a defendant to plead guilty’.Footnote 62 Whether or not these changes have increased the numbers pleading guilty is a difficult empirical question. Making the discount fixed and clear increases its effectiveness as incentive. But making the maximum sentence discount conditional upon defendants pleading guilty at an earlier time, when they have less disclosure, reduces its attractiveness as an incentive. So, one might well expect fewer defendants to plead guilty where a discount is made conditional upon an early plea than would occur in a system that gave the same discount at a later stage. But one can also argue that many defendants faced with this decision at the first Magistrates’ Court hearing may be psychologically less well placed to face the risks of a heavier sentence at trial than they would be later in the process. If this is true, then making the maximum discount conditional upon a plea at the early plea procedure will result in more guilty pleas, and the claim that it has increased the pressure to plead guilty is justified.Footnote 63

It is not plausible to deny that innocent defendants will never plead guilty in order to obtain reduced sentences, but in their justifications for changes that increase the various savings that can result from guilty pleas the judiciary have tended to either minimise or ignore this risk.Footnote 64 Defendants are meant to be protected from the ‘improper’ pressure to plead guilty said to arise when judges indicate to defendants the different sentences available on pleading guilty and following trial – a protection that has no obvious rationale.

Justifications Offered in the Court of Appeal when Determining Convictions as Safe

Our system, with its reliance on guilty pleas accompanied by sentence discounts, has been criticised for putting considerations of cost and effectiveness ahead of the usual characteristics attributed to trial – accuracy in verdicts, and fairness to defendants. Much of this criticism has been directed to our judiciary, as authors of reports recommending reforms, members of the Sentencing Council, and as sitting judges who fail adequately to acknowledge the pressure to plead guilty arising from sentence discounts.Footnote 65 But these developments, in which the judiciary have played a leading role, create particular difficulties for those judges who sit in the Court of Appeal, and have to decide which convictions are safe, and which constitute miscarriages of justice. The actual problem facing these judges is that they cannot use considerations of costs and effectiveness which have led us to our current system of summary or negotiated justice, when articulating reasons why individual convictions should not be quashed. Hence our view that this is an example of what Calabresi and Bobbitt called ‘tragic choices’.

Let us consider two recent judicial pronouncements on the nature of guilty pleas. In the Supreme Court in Asiedu in 2016, a terrorist explosives case, Lord Hughes (formerly Vice President of the Criminal Division of the Court of Appeal) refused to allow an appeal against a guilty plea conviction where there had been a serious non-disclosure that might well have resulted in a successful appeal if the conviction had been the result of a trial, on the basis that:

A defendant who pleads guilty is making a formal admission in open court that he is guilty of the offence. … once he has admitted such facts by an unambiguous and deliberately intended plea of guilty, there cannot then be an appeal against his conviction, for the simple reason that there is nothing unsafe about a conviction based on the defendant’s own voluntary confession in open court.Footnote 66

And in R. v Caley in 2012 Lord Justice Hughes (as he then was) defended the practice of reducing the sentence discount for pleading guilty, where defendants delay their decision until their lawyers have full knowledge of the case against them, on the basis that:

… whilst it is perfectly proper for a defendant to require advice from his lawyers on the strength of the evidence (just as he is perfectly entitled to insist on putting the Crown to proof at trial), he does not require it in order to know whether he is guilty or not; he requires it in order to assess the prospects of conviction or acquittal, which is different.Footnote 67

In both of these statements Lords Hughes is insisting that guilty pleas are (at least for the legal processes associated with determining guilt) factually accurate confessions, by the guilty, of the crimes that they have committed. As such, rather than being a suspect form of evidence, something that may even support more liberal rights to appeal than other kinds of process leading to conviction, they are treated as ultra-safe – justifying pleas, for example, obtained in circumstances where defendants may have been unaware of evidence that might be material to their defences.

These statements run contrary to the obvious dangers arising from offering defendants incentives to plead guilty. The attractiveness of these incentives relates to factors that have no evidential value in themselves. Rather they depend on such things as defendants’ attitude to risk, or the varied impact that a criminal record or a period of imprisonment will have on them in light of their personal circumstances.Footnote 68 There is also a predictable tension between these statements about guilty pleas, and the manner in which appeal courts approach appeals against conviction following trial. The qualities of fact finding, which the court habitually attributes to a full trial before a jury as part of its routine deference to this form of trial, are absent from guilty plea convictions. Instead, deference has to be directed to the guilty plea, in many respects requiring Lord Hughes (or other appeal court judges) to elevate the evidential status of the plea to a level that compensates for the absence of any substantive review of the evidence. It is difficult to accept that pleas offer such incontrovertible evidence of guilt, even if defendants were not offered sentence discounts as incentives to plead guilty. The ability of defendants to withdraw confessions made prior to trial, and the need for the probity and reliability of such confessions to be assessed at trials in light of all the surrounding evidence, acknowledges the fallibility of confession as a form of evidence. No matter how formal the circumstances of confessions, and how much legal assistance is provided at the time, judges cannot prevent defendants from giving evidence at trial which contradicts their earlier confessions. Nor could judges direct juries that the contradictory evidence should be given no weight on the basis that the earlier confessions constituted incontrovertible evidence of guilt. And it is worth pointing out the irony of Lord Hughes making such strong claims about the safety of convictions obtained through guilty pleas especially in the particular circumstances of Asiedu. The defendant in that case, at his earlier appeal against sentence, had been described by a different Court of Appeal as ‘a liar on an epic scale’.Footnote 69 His guilty plea resulted in a sentence which made him eligible for release on license 23½ years earlier than his co-defendants. It is hard not to presume that there is little evidential value in a guilty plea entered by an inveterate liar offered this level of inducement to plead guilty.Footnote 70

Non-evidential Bases for Restricting Appeals Against Guilty Pleas

In the Asiedu case Lord Hughes gave additional reasons for finding the conviction safe that did not depend on the evidential value of the plea:

… a defendant who is confronted by a powerful case may have difficult decisions to make whether to admit the offence or not. He will of course be advised that if he does plead guilty that fact will be reflected in sentence, but that general proposition of sentencing law does not alter his freedom of choice in the absence of an improper direct inducement from the judge …. He will always have it made clear to him that a plea of guilty, should he choose to tender it, amounts to a confession.

… the trial process is not a tactical game. A defendant knows the true facts; he ought not to admit to facts which are not true, whatever the evidence against him, and this will always be the advice he is given. If he does admit them, the evidence that they are true then comes from himself, whatever may be the other evidence advanced by the Crown.Footnote 71

Here Lord Hughes is making claims about the justice of holding defendants to their pleas irrespective of the pleas’ evidential value. He contends that it is fair to hold defendants to the expected consequences of their choices, without regard to the incentives offered for them to exercise their choices in a particular manner; and that innocent defendants who plead guilty are to some extent responsible for their own wrongful convictions. As a justification, perhaps this even assumes that innocent defendants have a moral duty to plead not guilty. Thus, having committed the ‘wrong’ of pleading guilty when innocent, defendants cannot be allowed to appeal against their own wrongful acts. These claims are clearly problematic. Is it appropriate to allow defendants to choose whether they should be found guilty or not? If the purpose of criminal procedures is to identify the factually guilty, then it is unclear why this factual question should be decided through someone’s choice, however free. It is one thing to decide what facts one believes exist by reference to the evidence available, it is quite another to claim that a state of facts exists because someone, even defendants, have chosen to confirm their existence.Footnote 72 Offering someone incentives to choose whether a particular state of facts exists is even less appropriate.

The first statement conflates choice with the fairness of choice. Choices (voluntary selections from alternatives) do not cease to be such just because one is given strong incentives to prefer one choice over another. Although one can speak of ‘coercion’, ‘lack of choice’, or ‘involuntary choices’ when the act of choosing is accompanied by the threat of something which one has a right to avoid,Footnote 73 defendants have no right to avoid trial if there is evidence sufficient to ground a charge (a case to answer), and no right not to suffer the appropriate sentence if they are convicted at trial. So, they cannot claim either that the prospect of trial constitutes coercion, or that the offer of a lesser punishment for pleading guilty is coercive. But the fact that someone chooses in full knowledge of what is expected to follow, and without a threat of illegal or immoral consequence, does not tell one whether it is fair or reasonable for them to have had to make that choice, or whether it is unfair or unreasonable for them to seek to undo that choice at a later date.Footnote 74

The second statement comes closest (if accepted) to justifying how the guilty pleas procedures are actually conducted, with defendants required to be formally warned that they should not plead guilty if they are in fact innocent. There are good reasons for such a warning, not least the harm done if those in fact guilty of crimes remain undetected because innocent persons falsely admit to crimes that they did not commit. But whatever wrong is committed by innocent defendants who falsely plead guilty, it is harsh to claim that this wrong is so great that it justifies a general refusal to examine the possibility that they may be innocent. It also seems to be unfair to place responsibility for this wrong solely with the defendant. To use a biblical metaphor, Eve and Adam ate the apple but the serpent encouraged them, the serpent here being the sentence discounts offered to all defendants who plead guilty. The harshness of relying on the ‘wrong’ of falsely admitting guilt to justify refusing to respond in nearly all cases to defendants who attempt to change their pleas at a later dateFootnote 75 and restricting their possibilities of appeal, is compounded by the loss of discount faced by defendants who refuse to plea until they have a full sense of the case against them.Footnote 76 And in a case like Asiedu, where the defendant decided to plead guilty in ignorance of a significant breach of the prosecution’s disclosure obligations, Lord Hughes’ approach blames defendants, and in some cases potentially innocent defendants, for decisions that they might not have taken but for wrongs committed by others.

Legal academics have offered other justifications for refusing to give credibility to defendants who wish to appeal their guilty plea convictions. As guilty pleas involve explicit or implicit negotiations they have been likened to the process of settlement within civil proceedings – a mutually beneficial contract which, once agreed, should not be re-opened by parties who later change their minds.Footnote 77 This rationale ignores the crucial difference between civil and criminal proceedings. The community as a whole normally has no independent interest in establishing whether a civil defendant did or did not commit the actions complained of. False convictions, by contrast, impact on the community by removing attention from those actually responsible for crimes, and wasting resources punishing and rehabilitating the wrong persons.Footnote 78 So the state has both an interest in getting convictions right in the first instance and quashing them where mistakes have been made thereafter. Additional weaknesses in the contractual justification lie with the absence, in the treatment of guilty pleas, of any of the factors that allow civil parties to re-open settlement contracts. Misrepresentation, or failure to disclose information that the other party had a duty to provide, would be expected, where serious, to allow the disadvantaged party to avoid the settlement contract.Footnote 79 Juliet Horne has discussed whether the judicial treatment of guilty pleas can be justified on the basis that a guilty plea is a delegation of the jury’s function to the defendant.Footnote 80 Are defendants’ self-assessment, aided by counsel, of the cases against them whereby they convict themselves, ones where they regard the prosecution evidence as sufficiently strong that they would expect a jury to convict? Is this akin to the kinds of self-certification processes that one finds in certain regulatory regimes? This is an interesting rationale but, as she concedes, it cannot explain current practice, as a genuine commitment to an accurate self-assessment would not lead to incentives to form such a judgement at the earliest opportunity. Nor would it justify an inability to alter such self-assessments where evidence had been wrongfully admitted or excluded, or not disclosed.

The weakness of the justifications given for restricting appeals against guilty pleas points to the fact that these normative rationales are not the operative reasons for such restrictive practices. Further evidence of this is provided by developments within both the US and the UK where the use of the plea has developed in a manner which excludes the possibility of some of these rationales, without any lessoning of appeal courts’ resistance to appeals against guilty plea convictions. In the US with the development of the Alford plea,Footnote 81 we have a situation in which defendants can plead guilty and earn their sentence discounts, whilst still asserting their innocence. This removes any possibility of treating guilty plea convictions as evidence of guilt, or expressions of remorse, or factual evidence that has misled the court. The court is left solely with the status of such pleas as waivers of rights of appeal – an act that defendants have chosen voluntarily to make in the knowledge of the consequences, and this has to stand alone as a justification for the refusal to allow appeals against conviction.Footnote 82 In the UK, the equivalent of Alford pleas occur when defendants plead guilty whilst still insisting to their counsel that they are innocent. In R v DannFootnote 83 the defendant accompanied his plea with a signed statement declaring that he was not guilty and was only pleading guilty in response to an offer not to prosecute his wife if he did. On appeal, the statement was held to make no difference to the ‘unequivocal’ nature of his plea, and the restrictions on appeal which followed, although there was no claim in this case that the plea itself was evidence of the defendant’s guilt.Footnote 84 Thus the difference here between the US and the UK is more a matter of form than substance – in the US the trial court is made aware of the claim of innocence at the time of the guilty plea, whilst in the UK this knowledge remains with defendants’ counsel.

Ongoing Reasons for the Resistance to Guilty Plea Appeals – Back to Workable Relationships?

It is difficult to quantify the increased workload that could arise if the Court of Appeal adopted a more liberal attitude towards appeals against convictions based on guilty pleas. However, we can consider some figures that give a sense of the size of the problem. For example, the Court of Appeal heard 215 conviction appeals in 2016–17.Footnote 85 Given the restricted grounds for appealing guilty pleas, we can assume that few if any of these appeals followed guilty pleas. In 2016–17 the CPS obtained convictions through trial in 7,806 cases, some 8.80% of convictions (61,808 guilty pleas were 70.10% of overall convictions).Footnote 86 As 215 cases were appealed, there was an appeal rate in relation to convictions after trial (relying on our assumption that there were very few guilty plea appeals) of 2.75%. Although of course one would expect it to be considerably less, if the same appeal rate occurred with their guilty plea convictions the Court of Appeal would have to hear nearly an extra 1,700 cases. This would represent approaching an eight-fold increase in the Court’s workload. In addition, there would be an increase in the workload of the Crown Courts, who would have to conduct trials originally avoided through the plea. If the current statutory bar against appeals from Magistrates’ Courts guilty plea convictions were removed, there is a similar potential for a huge increase in the appeal workload of the Crown Court. In 2018 there were 4,737 appeals against conviction heard in the Crown Courts.Footnote 87 We assume that few of these would have involved guilty pleas.Footnote 88 To get a rough sense of the appeal rate applicable, we can look again at the 2016–17 CPS figures, this time for convictions in the Magistrates’ Courts following trial: 28,424.Footnote 89 If 4,737 is treated as the number of appeals from CPS convictions at trial in 2016–17 it would represent an appeal rate of 16.67%. There were 390,344 convictions following guilty pleas in the Magistrates’ Court in 2016. If 16.7% of these were appealed this would generate over 65,080 appeals! This is, of course, quite unrealistic in many respects. Nevertheless, these figures illustrate what we already know – the dependence of our criminal justice system on guilty pleas at trial level creates a situation in which granting any increased rights of appeal to those who have pleaded guilty could be extremely costly.Footnote 90

The difficulties of allowing appeals against guilty plea convictions is not simply a matter of numbers. The immediate problem in almost every case is the lack of a transcript of evidence.Footnote 91 With appeals against convictions following trial, the Court of Appeal, or other appeal body, assesses the significance of any procedural error, or new evidence, in light of the whole of the evidence. Where evidence is disputed, they assume that the jury accepted the prosecution’s version of events and are reluctant to form a different view (hence the accusation of undue deference to juries). This method is not open to them with guilty pleas. The Court cannot rely on a prior assessment of the evidence. It must form its own view of the prior evidence and, in most cases, this will only be the evidence disclosed to the defence up to the moment when the guilty plea was entered. This also goes some way to explain the appeal court’s reluctance to consider new evidence. Being unable to assess the new evidence in light of the evidence presented at trial, it has little against which to balance that evidence when considering the safety of the conviction. Evidence which, by itself, shows that the defendant could not have committed the crime does not require any weighing. But, as the extensive case law on the right to compensation following successful appeals against conviction has consistently recognised, one rarely encounters new evidence that establishes beyond any reasonable doubt that a defendant could not have committed the offence in question.Footnote 92

As well as the difficulties of hearing guilty plea appeals, there are also difficulties with any possible remedy. If the Court of Appeal decides that a guilty plea conviction is unsafe it must either quash the conviction per se or quash the conviction and order a trial/re-trial. The latter outcome raises all the issues which currently bedevil the Court when considering whether to order re-trials. The longer the delay between a conviction and the order for retrial, the less likely it is that the trial will be either fair or effective. Witnesses forget, move and die. Where this undermines the prosecution case one has the prospect of defendants being acquitted due to lack of formerly available evidence. Where the deterioration affects defendants’ cases, we have the prospect of ‘re-trials’ that will appear unfair in light of evidence, or potentially exclusionary evidence, no longer available. The absence of a trial transcript also reduces the Court’s ability to impose alternative convictions rather than sustain convictions. This power arises following successful appeals from convictions following either trial or a guilty plea.Footnote 93 But in the case of early guilty plea convictions there will have been no articulation or exploration of the defence case, making it difficult to justify alternative offences, particularly as the court is unable to rely on the plea as evidence of guilt.

The resources and law and order implications of increasing the right to appeal guilty plea convictions rarely, if ever, feature in Court of Appeal judgments. Instead we find statements like those of Lord Hughes which, as we have tried to illustrate, are not dissimilar from the statements of other senior judicial figures over one hundred years earlier in their adamant opposition to the setting up of a Court of Criminal Appeal. Hence our view that these statements are an example of tragic choices – the use of value reasoning to defend institutional arrangements put in place for other reasons, particularly those of cost and efficiency. However, one should not interpret the absence of an express discussion of these factors and the attempt to justify guilty plea convictions on the basis of ideas of truth and moral wrongdoing as no more than a judicial smokescreen. There are other reasons why these considerations of cost and efficiency would not feature in the discourse of any Court of Appeal. The Court’s role is to distinguish safe from unsafe convictions. It is not open to the Court to identify the number of appeals that it believes the Court could manage, and pronounce the applications made next in time as automatically ‘safe’. In this the Court of Appeal is no different from any other court. It has to treat like cases alike. As such, the discourse through which it rations access to itself and the courts which it supervises has to be based on distinctions which it can draw, and justify, between convictions which it finds safe, and those it finds unsafe. In constructing its reasons for finding guilty plea convictions safe, it has to draw upon the same discourse of truth, and rights, with which it constructs safe and unsafe convictions on appeals from trials. Whether judges convince themselves of the justice of their current treatment of guilty pleas is an open question. But from an external perspective, the attempt to justify a near blanket ban on guilty plea convictions has echoes of the 19th century judicial resistance to any appeals against jury verdicts except on points of law, as expressed by Baron Parke in the quote at the start of this article – a view which, if our system ever evolves in a manner that dispenses with guilty pleas, may be viewed as sanguine, if not smug complacency.

Part Four: Moving on from the Current Position?

There is little evidence that our recent dependence on guilty pleas is going to lessen in the near future. A proposal to increase sentence discounts for guilty pleas (from one third to one half) was made as recently as 2010.Footnote 94 This proposal was not shelved because of its effect on the potential safety of convictions, but principally because the government felt that it might result in sentences, particularly for sex crimes, that the public would regard as too lenient.Footnote 95 The CPS are committed to maintaining or increasing the percentage of convictions obtained through guilty pleas at the first crown court hearing, as evidenced by their selection of this as a performance indicator.Footnote 96 The Ministry of Justice declines to set a target for guilty pleas, as this ‘could discourage prosecution of hard-to-prosecute cases or encourage unreasonable pressure on defendants to plead guilty early’.Footnote 97 But at the same time, it treats avoiding cracked trials as one of the primary measures of its own efficiency. As four out of five cracked trials are the result of defendants entering late changes of plea, encouraging more defendants to enter early guilty pleas will demonstrate the Ministry’s increased efficiency.Footnote 98

Meanwhile, those who draw attention to the potential for real injustices associated with guilty plea convictions have great difficulty in advocating their diminishing, in light of the cost of offering trials to many of those persons currently pleading guilty. Campbell, Ashworth and Redmayne, who criticise guilty pleas for their failure to provide the same assurances of accuracy and fairness as come with trial, question whether we could afford even to review prosecution evidence in guilty plea cases without some compensating reduction in the resources needed to try those who plead not guilty. Their argument is principally directed to the level of discounts that should be available, proposing a limit of 10% on the sentence reduction offered for pleading guilty.Footnote 99 McConville and Marsh question the effectiveness of sentence discounts, relying on a Canadian study which concluded that 70% of those who plead guilty might still be expected to do so without any reduction in sentence.Footnote 100 They similarly question the need for sentence discounts to reduce progressively in order to save the costs of ‘cracked’ trials.Footnote 101 Reducing the levels of sentence discount reduces the incentives for defendants to plead guilty, and increases the plausibility of judicial claims that guilty pleas offer a safe basis for convictions. However, unless the reduction in the size of discounts was accompanied by a reduction in the sentences normally imposed after conviction at trial, it would result in a significant increase in the prison population.Footnote 102 In addition, any claim that a fixed percentage reduction in the automatic discount for pleading guilty would make such convictions safe needs to take account of the factors that will alter the impact of that reduction: the ability to choose lesser charges, and the ability to agree facts which minimise the severity of the offence, and the choice of whether to charge persons close to the defendant.

Should we seek to protect those persons who might be more vulnerable to the pressure to plead guilty when innocent?Footnote 103 This raises problems of identifying vulnerability. Vulnerability may arise from the general capacity of the individual (as with mental illness), or their personal circumstances, as with those who cannot afford the financial costs of their defence, or have employment, business or family responsibilities that make it imperative for them to avoid or reduce their period of custody. It may also arise from the particular circumstances of the offence, as occurs when the defendant lies on the cusp of a prison sentence and therefore may be able to avoid custody through pleading guilty.Footnote 104 Or it may arise through a combination of factors. Alongside the issues of identifying who is to be considered vulnerable, one has to consider at what point in the process this element of vulnerability should be identified, and what protection should be afforded? Since the plea crucially affects the procedures that follow, this assessment needs to be made prior to the decision to plead. If the guilty pleas of the unidentified vulnerable are void or voidable, one faces the prospect of having later to restart procedures and processes of preparing for trial which, with sufficient delay, may no longer be possible.

If procedures could be put in place which identified the vulnerable, what response is appropriate? Simply to exclude them from the ability to plead guilty and require them to face a trial would, without further adjustment, result in those who were convicted at trial spending longer in prison than more ‘able’ defendants who had been allowed to plead guilty and receive their discounted sentences. So, if vulnerability were identified by reference to factors such as disability, socio-economic status, or ethnic group, the advantages of greater certainty that their convictions were justified by the evidence would have to be weighed against the increase in penalties that this group would on average face compared with other persons who are convicted of the same crimes, but have been able to plead guilty and achieve reductions in their sentences.Footnote 105 One could avoid this consequence by allowing the vulnerable who opt for trial to obtain the same discounts as the able who plead guilty. This would be controversial, as the justifications given for discounts (costs saved, witnesses and victims spared from having to testify, etc.) would be absent in such cases. The current adjustment for the vulnerable is restricted to circumstances where it is unreasonable for them to enter a guilty plea at the earliest opportunity, in which case they may still receive the full discount for a late plea. The focus of this exception (and the only specific example provided in the guidelines) is a person who fails to understand that the acts they are accused of committing constitute a criminal offence.Footnote 106 The guidelines expressly distinguish between failing to understand that an offence has been committed (where delay in entering a plea will be excused) and failing to understand the strength of the prosecution case (where it will not).Footnote 107 This exception does not seek to protect those who, for reasons of mental capacity or external pressures, might be particularly inclined to plead guilty despite innocence in order to reduce the severity of their sentence.

In a discussion of the possibilities for change, one needs also to take account of the presence or absence of pressure for reform from outside the legal system, most notably from the mass media and the political system. Public confidence in the criminal justice system is a recognised pre-condition to its efficient operation, and miscarriages of justice have been credited, within both the media and Parliament, as something that can undermine that confidence. The media reports on miscarriages in terms of the factual innocence of those convicted, whereas, as recently emphasised by Baroness Hale: “Innocence as such is not a concept known to our criminal justice system”.Footnote 108 Miscarriages are constructed within our legal system in terms of errors of procedure or new evidence which, had the former not occurred or the latter been available, might have made a difference to the verdict (guilty or not guilty) in a criminal trial. By contrast, the media focus on a person’s factual innocence, and in consequence one might have expected this media focus to provide a basis for critical reporting of guilty plea convictions.Footnote 109 After all, it is not difficult to understand that significant sentence reductions offered in exchange for guilty pleas represent a pressure to plead guilty that can be expected to influence at least some innocent defendants to plead guilty. But there appears to be no general dissatisfaction within the media over convictions obtained through guilty pleas. Indeed, one of the factors normally required before the media give credence to claims of wrongful (factually innocent) conviction is that the person involved continues to proclaim their innocence. Whilst confessions obtained in custody and subsequently retracted are no longer given the status that they formerly had, pleading guilty provides a formidable obstacle to mounting a press story (let alone a media campaign) that a factually innocent person has been wrongfully convicted.

Another factor that inhibits media pressure for change in the treatment of guilty pleas is the role played by the CCRC.Footnote 110 Prior to 1997 there was no procedure which could quash a conviction obtained through a guilty plea in the Magistrates’ Court. Where evidence emerged that exonerated the defendant the only procedure open to them was to seek a pardon. Since the CCRC began operating in that year there is now a process by which any Magistrates’ Court conviction which the media regard as unsafe (which for the media invariably translates as a factually innocent defendant) could be reviewed by the Crown Court, following application to the CCRC and referral.Footnote 111 With Crown Court convictions, the Court of Appeal’s resistance to reconsidering guilty plea convictions is compensated for, to a limited extent, by the CCRC’s right to refer guilty plea cases. However, in view of their statutory authority, the CCRC can only refer cases where there is a ‘real possibility’ of success, which requires it to take account of the restrictions which the Court of Appeal has placed upon guilty plea conviction appeals. This severely limits its ability to operate as a means to rectify potential wrongful (both in terms of factual innocence and breaches of rights) convictions arising from guilty pleas. Nevertheless, the CCRC offers a mechanism whereby cases which may have gained media attention can be re-examined by the Court of Appeal, even in guilty plea cases. Such referrals may deflect media criticism of potentially unremedied miscarriages and the demands for reform which might accompany these, and they do not require referral of a large number of cases to achieve this. Only a small percentage of those who had pleaded guilty apply to the CCRC to have their convictions reviewed. In her study of guilty plea applications to the CCRC over a twelve-month period Juliet Horne identified 235 such cases.Footnote 112 This is a significant percentage of the applications to the CCRC (21%), but a very small number relative to the number of annual guilty plea convictions. Only a tiny number of these applications resulted in a referral to the Court of Appeal for a review of conviction. For the first sixteen years of their existence only 49 guilty plea convictions were referred by the CCRC for a review of their safety.Footnote 113 This is a manageable number of extra appeals. In effect, the CCRC operates as a gatekeeper, identifying exceptional cases where the available evidence provides a powerful indication of innocence despite the guilty plea. Whilst the CCRC have never limited themselves to cases which find support in the mass media, the Commission plays an important role in offering a means by which such cases can be investigated by a body which is regarded as impartial. As with miscarriages arising from trial, these investigations reduce the likelihood that individual cases will be reported in the press in terms of systemic failings and, as such, depress the pressure for reform.

Summary

We have attempted to show that the judicial treatment of appeals against conviction following a guilty plea is an example of tragic choice – the need to justify procedures by reference to values such as rights and truth, and without reference to the considerations (cost, efficiency, crime control etc.) which have led to their introduction. Tragic choice is present when judges seek to justify convictions following trial, but this is heightened in guilty plea cases. This is not just a result of the far larger number of convictions that arise from pleas rather than trials. When it comes to guilty pleas, the court has to attribute the same values (truth and rights) to the conviction that follows a plea as it attributes to a conviction following trial, but without the benefit of the features of trial which help to make that attribution plausible (lay judgement, hearing witnesses, cross-examination, etc.) Recent changes to the plea system (in the interests of efficiency) such as restricting maximum sentence discounts to pleas made at the earliest opportunity, further distance guilty pleas from the protections afforded by trial, and compound the difficulties in justifying these convictions as ‘safe’.

Guilty pleas also offer the judges little scope for identifying or remedying errors, as there is no transcript of evidence to review, or a basis to substitute alternate convictions. A general willingness to allow appeals against guilty plea convictions could not only lead to a large increase in the number of trials but, without a strict time limit on the right to appeal, would lead to trials which repeat all the difficulties of ordering fair re-trials long after the original investigation. In the face of these difficulties, the courts have placed the strictest of limitations on appeals, basically restricting them to circumstances where appellants are able to show that they did not intend to admit to facts that constituted the offense for which they were convicted. Even circumstances that would ordinarily justify an appeal against a trial conviction, such as significant non-disclosure or plausible and probative new evidence can only exceptionally justify a successful appeal against a guilty plea conviction. Thus, we have a situation in which a procedure which, on its face is less capable of identifying guilt than a trial, has to be defended on the basis that it is overwhelmingly more capable of identifying guilt (or so fair as to justify disregarding the possibility of innocence). The criminal justice system for England and Wales has, since 1907, had an institutional means to recognise the undeniable possibility that trials can in a small (relative to its critic’s beliefs) but significant number of cases perpetrate miscarriages of justice. But with guilty pleas we have, for reasons of cost and efficiency, reached a situation where the Court of Appeal cannot provide a remedy for miscarriages, and must instead, like the judges of the 19th century, claim the relevant procedures are so safe that there is little or no need for review, even in cases of procedural irregularity (short of abuse of process) or new evidence (short of exoneration). At present, there is no reason to think that this situation will be ameliorated,

Conclusion

Different pre-trial and trial procedures as they have evolved, whether through slow evolution or more abrupt legislative change, can be shown to throw up different potential for miscarriages of justiceFootnote 114 and, at the same time, different challenges for appeal practices, procedures and doctrine. The appeals process is the place within the criminal justice system where claims that our procedures for obtaining convictions are based on acceptable values (truth, rights, fairness, etc.) are most in evidence and, at the same time, most exposed. As the practices of the criminal justice system evolve, the procedures which have to be justified when defendants appeal alter. While tragic choice is, we would argue, a constant feature underlying the justifications offered in criminal appeals, what has to be justified by the appeal courts is not constant. There are obvious parallels between the reliance on conviction through incentivised guilty pleas, and reliance on convictions obtained through ‘coerced’ confession evidence.Footnote 115 The latter has undergone a process of change, with the opportunities for such coerced confessions reduced through the reforms introduced by the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, and the need to rely on them diminished through the increased availability of new forms of forensic evidence (DNA, CCTV, etc). These changes alter what is ‘normal’ at trial, and what needs to be justified on appeal. That said, our current reliance on guilty pleas is such that it is difficult to see what changes are going to relieve the judiciary from having to make the strong claims for their evidential value and fairness which they are currently making. In so doing, and thereby refusing to re-examine guilty plea convictions in many, if not most, circumstances, they expose themselves to accusations that they have been, and continue to be, indifferent to justice, or at least sanguine about the improbability of its miscarriage.

Notes

Quoted in A.H. Manchester, Sources of English Legal History: Law, History, and Society in England and Wales 1750–1950 (London: Butterworths, 1984), 179. Baron Parke (later Lord Wensleydale) was a senior judge sitting as a Law Lord until his death in 1868. Opposition by senior judicial figures was significant in preventing the setting up of a Criminal Court of Appeal during the 19th century in which some 31 Bills trying to do so failed, before one eventually succeeded in 1907.

See R. Pattenden, English Criminal Appeals 1844–1994 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996) especially ch 1 ‘The Making of the Court of Criminal Appeal’ and ch 2 ‘The Court of Appeal, Criminal Division: An Overview’; R. Nobles and D. Schiff Understanding Miscarriages of Justice (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) ch 3 ‘Remedying miscarriages of justice: the history of the Court of Criminal Appeal’, esp 41–55.

As background to some of wide-ranging issues involved, see: M. Shapiro, ‘Appeal’ (1980) Law & Society Review 629; R. Nobles and D. Schiff, ‘The Right to Appeal and Workable Systems of Justice' (2002) 65 Modern Law Review 676; R. Nobles and D. Schiff, ‘The Criminal Cases Review Commission: establishing a workable relationship with the Court of Appeal’ [2005] Criminal Law Review 173; R. Pattenden, ‘The standards of review for mistake of fact in the Court of Appeal, (Criminal Division)’ [2009] Criminal Law Review 16; M. Elliott and R. Thomas, ‘Tribunal Justice and Proportionate Dispute Resolution’ [2012] Cambridge Law Journal 297.

Stated clearly by Lord Tucker in the Privy Council case of Aladesuru v R [1956] AC 49, at 54–5. ‘… it has long been established that the appeal is not by way of rehearing as in civil cases on appeals from a judge sitting alone, but is a limited appeal which precludes the court from reviewing the evidence and making its own valuation thereof.’

See L.H. Leigh, ‘Lurking doubt and the safety of convictions’ [2006] Criminal Law Review 809; and succinctly, R. Grist, ‘Lurking doubts remain’ Criminal Law & Justice Weekly 2012, 176(22) 313–14. Success will only occur in ‘exceptional’ cases’, see R v Pope (John Randall) [2012] EWCA Crim 2241.

See, for a clear example, The Report of the Royal Commission on Criminal Justice, Cm 2263 (London, HMSO, 1993) ch 10, para 3; also S. Roberts, ‘Fresh evidence and factual innocence in the Criminal Division of the Court of Appeal’ [2017] Journal of Criminal Law 303, esp 304–5, and n 8.

M. Zander, ‘The Criminal Cases Review Commission, the Court of Appeal and jury decisions – a better way forward’, Criminal Law & Justice Weekly 2015, 179(4), 179(12), 179(7); M. Zander, ‘The Justice Select Committee's report on the CCRC – where do we go from here?’ [2015] Criminal Law Review 473; H Quirk, ‘Identifying Miscarriages of Justice: Why Innocence in the UK Is Not the Answer' (2007) 70 Modern Law Review 759; S. Roberts and L. Weathered. ‘Assisting the Factually Innocent: ‘The Contradictions and Compatibility of Innocence Projects and the Criminal Cases Review Commission’ (2009) Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 43.

This is not to deny that such evidence is available. Cheryl Thomas’ analysis of jury verdicts, for example, offers reassuring evidence that they are not biased against black defendants, that they convict at a higher rate where offences involve the most direct evidence of guilt, and at lower rates when the offence requires a judgement on the intentions which accompany the relevant acts; but that less than a majority of juries fully understand the judges’ legal directions: see her ‘Ethnicity and the Fairness of Jury Trials in England and Wales 2006–2014’ [2017] Criminal Law Review 860; and ‘Are Juries Fair?’ (UK Ministry of Justice Research Series, 01/10, 2010). Whilst this evidence is indeed generally reassuring, it is not the source for judicial deference to jury verdicts.

For a brief discussion of this issue, in the context of expert evidence, see W.E. O’Brian, ‘Fresh Expert Evidence in CCRC Cases’ (2011) 22 King’s Law Journal 1, esp 3–7.

The relevant legislation is the Criminal Appeal Act 1968, section 2, as amended by the Criminal Appeal Act 1995, section 2, which legislation does not define what constitutes ‘unsafe’, except negatively. For example, the Court may not consider an appeal based on the claim that a defendant should have been entitled to elect for summary trial but was denied this right due to an erroneous over-valuing of the property involved: 1968 Act, s. 1(3).

For example, judges make up eight of the fourteen members of the Sentencing Council: https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/about-us/council-members/.

The Criminal Procedure Rule Committee consists of the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales and 17 people appointed by the Lord Chief Justice and the Lord Chancellor under section 70 of the Courts Act 2003 https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/criminal-procedure-rule-committee/about#membership.

For an example of judges struggling with statutory procedural requirements which clash with their concepts of a fair trial, see R v B [2003] EWCA Crim 319 at paras 26 and 27 – historic sex abuse conviction based on the complainant’s uncorroborated testimony, following statutory removal of the requirement for corroboration – overturned on the basis of ‘a residual discretion to set aside a conviction if we feel it is unsafe or unfair to allow it to stand. .. even where the trial process itself cannot be faulted.’

See R. Reiner, S. Livingstone and J. Allen, ‘From law and order to lynch mobs: crime news since the Second World War, in P. Mason (ed.), Criminal Visions: Media Representations of Crime and Justice (Devon: Willan Publishing, 2003), ch 1. High profile crimes ‘signal’ the problems within society that require reaction, see M. Innes, ‘“Signal crimes”, detective work, mass media and constructing collective memory’, also in P. Mason (ed.) ch 3. For a classic study of criminal justice responding to media created perceptions of crisis, see S. Hall et al, Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order (London: Macmillan, 1978).

We have, in particular, analysed the responsibility and role of the Court of Appeal by drawing on G. Calabresi and P. Bobbitt’s concept of tragic choice in their book Tragic Choices (New York: W.W.Norton, 1978). Tragic choice describes the situation when chosen first order institutional arrangements have to be defended at a secondary level without acknowledging the inherent sacrifice of values in those earlier choices. See R. Nobles and D. Schiff, ‘The Never-Ending Story: Disguising Tragic Choices in Criminal Justice’ (1997) 60 Modern Law Review 293.

In their 2018–19 annual report the CPS record convictions in 83.7% of their cases, with convictions obtained via guilty plea in 76.7% of cases. Guilty pleas were therefore 91.64% of total convictions. See Crown Prosecution Service Annual Report and Accounts 2018–9, HC 2286, p. 7. A breakdown of convictions obtained in the Magistrates’ and the Crown Courts over the three financial years 2016–7, 2017–8, and 2018–9 is provided at pages 22 and 25. Ignoring convictions obtained in absence (mostly minor traffic offences dealt with in the absence of the defendant) the percentage of convictions obtained through guilty pleas over these three years in each court were: Magistrates’ Courts: 93.21%, 92.7%, 93.56%; Crown Courts: 88.79%, 88.68%, 88.38%.

See Lafler v Cooper 566 U.S. Rep. 156 (2012) and Missouri v Frye 566 U.S. 134 (2012) decided on the same day and approving this statement taken from R. Scott and W. Stuntz, ‘Plea Bargaining as Contract’ (1992) 101 Yale Law Journal 1909, at 1912. The Supreme Court made this observation in light of 97% of federal convictions and 94% of state convictions being the result of guilty pleas. The manner in which our guilty plea system resembles that in the US is not limited to numbers – see the common features identified by Lord Brown in McKinnon v US (2008) UKHL 59, para 34. Even in the US the change from an informal plea-bargaining system to the formal one of today is of recent origin: see D.J. Newman, Conviction: The Determination of Guilt or Innocence Without Trial (Boston: Little, Brown and Co, 1966).

The Code for Crown Prosecutors 2018 states that the prosecution, when considering whether to accept a guilty plea, must not do so ‘just because it is convenient’, and that they must ensure that ‘the court is able to pass a sentence that matches the seriousness of the offending, especially where there are aggravating features.’ CPS code of guidance, 2018, paras 9.4 and 9.2. It is difficult to see this as anything more than a directive not to abandon more serious charges where defendants have no serious prospect of acquittal. If there is any doubt that the prosecution will succeed, then it is not simply a matter of ‘convenience’ to accept a lesser charge. The ‘evidence’ test for charging identifies the ‘space’ for prosecutors to accept pleas to lesser charges. Charging only requires judgement that a conviction is ‘more likely than not’, whilst a court is required to be ‘sure that the defendant is guilty’. (para 4.7). https://www.CPS.gov.uk/publication/code-crown-prosecutors.

In the U.S. in 2001 (the last year when the relevant data was collected and published) the average length of incarnation for defendants who pleaded guilty in the Federal courts was 61.6% less than the sentence imposed on those who were convicted at trial. (See Compendium of Federal Justice Statistics, Table 5.3: https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=599.