Abstract

As exposure to climate change increases, there is a growing need for effective adaptation decision support products across public, private and community sectors and at all scales (local, regional, national, international). Numerous guidance products have been developed, but it is not clear to what extent they meet end-user needs, especially as development has been fragmented and many products lack continuing support, learning and improvement. It is timely to address the development of more intentional and coordinated support strategies that draw on the experience to date and what end-users themselves say they need. We have taken such an approach to co-design future support strategies for Australia at national and sub-national (sectoral, locational and/or jurisdictional) levels. Several supporting frameworks are introduced to assist in the clarification of common needs (e.g. incorporation of leading adaptation practices) versus differentiated needs across sectors (e.g. a ‘decision entry points’ framework) and individual organisations (e.g. a ‘decision domains’ framework). The collaborative process also identified key principles that should underpin national and sub-national support strategies and product development. A comparison with international experience indicates that the findings and principles should also be relevant to other nations, and to international and sub-national agencies developing adaptation support strategies and products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There is growing evidence of climate change impacts from both extreme events and slow onset changes (IPCC 2014a). In response, climate adaptation experience and research have developed significantly, and public, private and community sector decision-makers are increasingly concerned about how to best incorporate adaptation into their risk and opportunity assessments, strategic and operational planning and individual decisions.

However, adaptation needs to progress from planning and assessment to action and to overcome numerous adaptation barriers and challenges (e.g. Ford et al. 2011; Moser and Ekstrom 2010; Webb et al. 2013).

To address these challenges, organisations require effective climate adaptation support products throughout the decision-making process, from strategic and operational planning through to impact, vulnerability and options assessment, decision-making, implementation and review. Adaptation support products include methodological and process guidelines, analytical tools, data and knowledge sources, as well as supporting services (e.g. training, skilling, advice, translation to context). Their physical manifestations are typically web-based portals, documents, or tools and ‘face to face’ or networked supporting services.

This need has resulted in a proliferation of decision support products and tools, especially in developed countries where the evolution of policy and decision support arrangements has varied according to a range of local political, economic and climate contexts (Ford and Berrang-Ford 2011). Within individual countries, products have been developed for specific sectors, jurisdictions and other audiences. Adaptation support for developing countries has often been linked to the broader development agenda (OECD 2009), including products developed by UNFCCC, UNDP, UNEP, World Bank, national aid agencies and non-government aid organisations. The private sector, at a national and international level, is becoming increasingly aware of the need to adapt and is developing products to support their needs (Agrawala et al. 2011; Rissik and Smith 2016; UNFCCC 2017).

However, it is not clear how effectively these products are meeting user needs, i.e. the extent to which users are aware of what is available, and when, how or whether to make use of them in their context. Co-operation between users and decision support product developers may help to ensure that design and content match the needs of users (Valls-Donderis et al. 2014). In addition, continual learning about adaptation planning, decision-making and review has not been well distilled and promulgated.

Using a collaborative process with a wide range of stakeholders across multiple sectors, we have addressed these concerns by identifying the following:

-

1.

how to combine the users’ own views on their priority needs with leading adaptation practices that have emerged in recent years

-

2.

common needs across users and needs that are highly differentiated by type of user.

From these findings, and a review of currently available support products, we also co-produced a set of principles to underpin improved support strategies at national, sectoral and jurisdictional/regional/local levels. While we have focussed on Australia as a case study, our review of international products and experience indicates that similar issues and approaches are relevant elsewhere.

2 The Australian case study and methodology

2.1 Australian context

Australia is highly exposed to climate change (IPCC 2014b). In the last decade, significant investment in adaptation research and applied risk assessment and planning has included federal funding for the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility (NCCARF 2017a), the CSIRO Climate Adaptation Flagship (CSIRO 2017), and programs at the regional scale (e.g. natural resource management programs) and local government level (e.g. the Local Adaptation Pathways, and the Coastal Adaptation Decision Pathways Programs). There has also been state government, local government and private sector adaptation support.

Many national, sector-specific and local adaptation support products have been developed in this period (Webb et al. 2014). The only truly national cross-sector product has been the (now dated) federal-funded guide for business and government (AGO 2006), while various guides have covered specific aspects of adaptation or sectors, e.g. coastal adaptation options (Griffith University 2013), natural resource management (Rissik et al. 2014). However, this has led to significant duplication and fragmentation of effort and learning, and many products have foundered for lack of critical mass, sustained resourcing and user input, understanding and confidence (Webb et al. 2013).

For these and other reasons, translation into proactive response by decision-makers has been patchy. A collaborative review of 20 Australian adaptation case studies (Webb et al. 2013) identified improved decision support strategies and products, and identification and sharing of leading practices, as key to improved adaptation capability and outcomes.

The lack of sustained effort has been compounded by a sharp reduction in government funding for adaptation in recent years and frequent changes in climate change policy and direction at all levels of government.

Adaptation effort in Australia is therefore at a watershed. The strong growth in experience and research, together with seed funding for planning, has supported progress by early adopters. However, in a future with more constrained government funding and most organisations still at best at initial stages in adaption planning, this foundation could easily be lost. This places a premium on developing and promulgating good practices and products to better support decision-makers.

2.2 The Leading Adaptation Practices and Support program and methodology

It was in this context that we undertook the Leading Adaptation Practices and Support (LAPS) program, working with stakeholders to identify their priority needs, including incorporation of leading practices into future products; to evaluate current products and services against those needs to identify significant gaps; and to co-develop national and sub-national strategies to address the gaps. The program was carried out in two project phases: LAPS1 (Webb and Beh 2013) and LAPS2 (Webb et al. 2014), and outcomes are summarised in this article.

We considered all stages of the decision-making cycle (awareness, planning, risk and options assessment, decision-making, monitoring and review). In phase 1 we sought input from multiple sectors (e.g. natural resource, primary and secondary industry, services, development, investment, public sector and non-government organisations) and varied geographic locations. In phase 2, we focussed on coastal settlements and infrastructure, identified as a high priority by nearly all stakeholders (including all levels of government), to test findings and proposed solutions.

We engaged with approximately 60 stakeholder organisations and individuals in the first phase, and 40 in the second phase, with some common between phases. Participants included federal, state and local governments; regional bodies; private sector peak bodies; corporations; non-government organisations; consultants and researchers. Two categories of stakeholders were represented:

-

Adaptation decision-making organisations, which included government, private and community sectors

-

Adaptation support providers and practitioners, who perform a variety of roles, including policy and standard setting, product development and delivery, knowledge brokering and advocacy, consultancy and research.

We conducted 40 unstructured interviews during LAPS1 and 40 semi-structured interviews in LAPS2. Unstructured interviews were summarised and analysed by the project team for themes and ideas to be tested in subsequent stages. The semi-structured interviews were transcribed and analysed using NVivo. We reviewed 20 Australian case studies (several ‘good adaptation practice’ studies identified by NCCARF (2013) and all of the projects funded under the federal Coastal Adaptation Decision Pathways Program). We also reviewed relevant peer-reviewed and grey Australian and international literature with a focus on the last 10 years and tested emerging insights through international conferences and teleconferences with experts in the field.

The project team carried out a stocktake and review of support products and services currently available in Australia and internationally covering approximately 300 individual products, categorised into three groupings (Webb and Beh 2013): 90 process support products that typically guide the user through steps in the adaptation cycle; 80 data products including climate, risk and adaptation options data; and 130 broader knowledge products, of which 30 were general adaptation portals, aiming to integrate access to the resources for users. Two thirds of the products reviewed were Australian, enabling us to drill down in the case study country in some detail, and at national, sectoral, jurisdictional and local levels. One third were internationally developed products including highly publicised/cited and generally better known examples. Products were discovered through Internet search and input from stakeholders, who also advised on product review criteria.

Four full-day and two 2-day workshops, ranging in size from 10 to 60 participants, and held over an 18 month period, were used to thoroughly test and refine provisional findings from all the above processes and to progressively co-develop practical adaptation support needs and future support strategies. This iterative process enabled progressive development of a stakeholder consensus on the findings and conclusions summarised in this article.

3 Developing user-driven national adaptation support strategies

This section summarises our findings from the collaborative research process. Early in the project, stakeholders informed us of characteristics associated with climate change adaptation that make adaptation framing, planning and decision-making distinctive, novel and challenging. These included the following:

-

the pervasiveness of climate impacts on natural and human systems, leading to new and complex interdependencies across sectors and issues;

-

the need to consider the range of time and spatial scales at which climate impacts, and responses are likely to play out;

-

significant uncertainties, especially for decisions with medium and longer-term consequences;

-

values and institutional arrangements, including roles, responsibilities and resources, which are rarely well aligned to the new challenge

With this as the context, we then identified

-

leading practices that should be included in adaptation support products

-

the extent to which user needs are common or differentiated

-

an approach to developing national and sub-national adaptation decision-making support strategies.

3.1 Incorporating leading practices into the adaptation process and support products

Users want process support products to incorporate leading adaptation practices. This is essential, as climate adaptation decision-making practice is still evolving and only just starting to be codified. The summary of identified leading practices is in Table 1 [Additional detail is provided at Online Resource 1].

-

1.

The overall adaptation process: a cyclical and iterative process with clear links to the well-established risk management methodology, enhanced with specific climate adaptation features, provides the most useful overarching framework for adaptation issues (Willows and Connell 2003; Jones and Preston 2011; IPCC 2014c). Figure 1 shows such a process with traditional risk management terminology alongside adaptation language for each step. Users find they can readily align such an approach with existing organisational and project risk management approaches, while also meeting special adaptation requirements.

-

2.

Continuing learning throughout the process: iterative processes, supporting learning and adaptive management, are crucial. Relatively ‘fast iteration’ between steps 1–3 (framing/scoping, risk/vulnerability assessment and available adaptation response options) can shift the emphasis from assessment to action in a more timely and focussed fashion, especially as potential adaptation response options and characteristics are increasingly codified (e.g. Griffith University (2013) for coastal response options). This is complemented by the medium/longer term monitoring, evaluation and review (Bours et al. 2014, 2015) which includes single, double and triple loop learning on the broader cycle (Pahl-Wostl 2009; Pahl-Wostl et al. 2013) and by active learning from the experience of others who have carried out similar adaptation initiatives. Such continuous learning approaches also require a cumulative approach to data and knowledge management from the outset.

-

3.

Sustained leadership and engagement: strong sustained leadership and effective stakeholder engagement are fundamental and required throughout the adaptation process (Moser and Ekstrom 2010; Webb et al. 2013). Approaches need to be tailored to the situation (Bisaro et al. 2016) and will evolve as the process unfolds, but only sustained effort will provide the organisational and social licence to progress, in what will often be new, fragmented and contentious terrain.

-

4.

Explicit and agreed framing and scoping: how an adaptation initiative is framed and scoped has a significant influence on all subsequent steps (de Boer et al. 2010; Brown et al. 2011; Fuenfgeld et al. 2012). Poor framing can doom a project to failure from the outset. This is an area poorly covered in current adaptation support products. There is no single right or wrong framing—rather choices that are likely to be more or less helpful to the issue at hand. There will often be a need to revisit initial framing decisions and assumptions as the project progresses. Table 1 lists several of the key areas of framing choice involved. These are usually interconnected, so best established as a set of consistent choices. For example, the pervasiveness of climate change into so many interconnected areas of the environment and society often raises the question of what should be included in the ‘systems of interest’, with associated issues of where to draw the boundary and appropriate spatial and temporal scales. This in turn can influence the extent to which framing needs to move from incremental into transformational territory, requiring broader stakeholder engagement and, very often, institutional change. All the previous choices will in turn shape the approach to mainstreaming and goal-setting.

-

5.

Evaluating risks and responses: many support products have focussed mostly on how to evaluate climate risks and response options. This can be at an overview level in step 1, but more definitively in steps 2 and 3. Table 1 summarises some of the leading practices identified, and indeed, many of these have also been identified in the literature (see also Online Resource 1). A common theme of these is the need for guidance that recognises a plurality of possible evaluation approaches to cover the diversity of adaptation contexts, but also helps the user, at an earlier stage, identify the methods, tools and data that are most appropriate for their circumstances, including the types of decisions they are actually facing (e.g. Hinkel and Bisaro 2016; Hinkel et al. 2016). Increasingly, useful guidance is also available on making adaptation decisions under deep uncertainty (e.g. Dessai and van de Sluijs 2007; Stafford Smith et al. 2011). Especially where more complex, broader and potentially transformational framing is required, individual decisions can be facilitated by viewing them as part of dynamic and flexible multi-decision adaptation pathways (Haasnoot et al. 2013; Maru and Stafford Smith 2014). Collectively, these evaluation good practices make it possible to move more rapidly from framing and analysis to decision and action.

The previous leading practices, identified through the collaborative process, will undoubtedly be added to and refined over time, but represent a current set that should be incorporated in future support products.

3.2 Meeting common and differentiated user needs

The sixth grouping of leading practices in Table 1 identifies product characteristics that are essential to meet common needs across users, but also allow highly differentiated needs to be met.

-

(a)

Authoritative products and processes

Decision-makers in government agencies, utilities, businesses and the community sector are increasingly recognising the need to develop climate adaptation responses. They have a growing range of motivations (e.g. responding to government policy and regulation; justifying climate risk investment to regulators; meeting board/directors statutory responsibilities and other professional standards; internal and external governance accountabilities to manage risks and opportunities; justifying contentious decisions to investors, to the community and in some cases to the courts). In these situations, decision-makers rely on the authority and currency of the guidance and approaches they have adopted. Therefore, stakeholders are seeking greater confidence in products, adaptation processes, information sources and data (e.g. climate scenario/projections and risk/hazard mapping), with continuous improvement and support required over time. Too often, users currently have to choose from a plethora of products, with no quality assurance or certainty of long-term support and update.

There was a strong call for definitive, preferably government-backed core products, co-developed with users, and endorsed by acknowledged experts, providing an authoritative resource to be relied on; and for a quality assurance process for both these and segment-specific products.

-

(b)

Meeting common and differentiated needs

-

(i)

Common needs across sectors and locations: there was a recognition that some product needs are common across sectors and locations, while others are highly differentiated by type of user. For example, the leading practices already referred to are relevant to all sectors/locations. Too much effort goes into rediscovering the approach to these common needs for each product, leaving few resources to address genuine differentiated requirements. Improved knowledge sharing, learning and collaboration are required, including formal sharing at the national, sector and jurisdictional levels as well as informal sharing and project based learning. Such common needs should be provided by authoritative cross-sector national (and potentially international) products.

-

(ii)

Differentiated needs by sector and location: National (cross-sector) products need to be complemented by demand- and user-driven sector, regional and local jurisdictional products. The ‘common’ adaptation processes often need translation into a sector’s distinctive language and business processes, and sectors/regions have different governance, legislative, climatic and other contexts that are relevant to stakeholders. More specific guidance on typical risks and available responses can also be included in sector-specific products. Many such sub-national and sectoral products have been developed in Australia, funded by both the public sector (e.g. Rissik et al. (2014) for natural resource management) and the private sector (e.g. ENA (2017) for the energy sector). However, to date such products have not had the advantage of being able to draw down from, and demonstrate consistency with, an authoritative national cross-sector product.

-

(i)

-

(c)

Reflecting multiple ‘decision entry points’ and decision types

Different sectors have specific business processes which are likely to require support from adaptation guidance. It is important to understand and map these as potential entry points into the decision-making processes. Several sector-specific business process and related ‘adaptation decision entry point’ frameworks were developed jointly with sectoral representatives. A local government example (Fig. 2) reflects a very wide range of decision entry points and also decision types (e.g. policy/planning, long-term investment, short-term operational), helping to identify and frame the main organisational focal areas. It also suggests necessary areas to be covered in sector-specific guidance products. Further examples for private sector built environment, insurance and funds/banking sectors are provided in Webb and Beh (2013: pp. 87-90).

-

(d)

Reflecting different stages of adaptation development, capacities and starting points

Adaptation decision entry points framework, showing the range of business processes for a sector where climate adaptation may need to be incorporated into decisions. This will vary significantly from sector to sector—the figure shows a local government example, and in this case, every process identified could require adaptation decisions (shown as stars). Analysing these can help sectors and individual organisations develop adaptation framing, scoping and management approaches and can also help structure differentiated adaptation support products. (Framework developed collaboratively with stakeholders). Note: arrows indicate some high-level interdependency, not a pre-determined sequence, users may and do start at whatever decision entry points fit their purpose

Differentiation of needs between individual organisations can also be significant, even for those within the same sector and jurisdiction. In particular, the stage of adaptation planning development, the level of adaptation management experience and capacity, and the desired starting point and sequence, will vary between otherwise very similar organisations, and can significantly influence the framing choices.

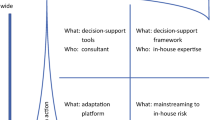

Thus, the organisation’s stage of adaptation development can affect the ‘decision-making domains’ involved and consequently the level of detail required. Four key domains were identified reflecting distinctive needs (Fig. 3).

These are

-

entry-level planning processes: a frequent starting point, with an emphasis on awareness raising, preliminary understanding of risks and potential responses, broad level planning and gaining stakeholder commitment to progress to more detailed stages. The process guidance products for this component can potentially be quite generic or at least have a major generic element;

-

complex decision-making processes: for more advanced users and including significant operational and investment decisions. It is likely that there are still common or ‘core’ requirements that can be useful across sectors, but also that more tailored sector-specific products and detailed data will have increasing value, complemented by a wide range of (generally) sector-specific analytical tools (e.g. hydrological, ecosystem, built environment assessment and modelling tools);

-

societal readiness and transformational change processes: which are frequently the most complex and least developed, as they can challenge existing values and institutions, requiring extensive stakeholder engagement and new types of knowledge; and

-

assurance processes: which may be for internal or external assurance and governance. These enable assessments of how well an organisation is addressing the adaptation challenge, including (for example) at the Board or Council governance level. Examples of utility include assessing progress in developing internal adaptation capability and responses; in external assurance processes such as those required by funds investors to evidence that companies and major infrastructure projects are tackling climate risks effectively; and in the increasingly influential building and infrastructure rating schemes.

Typically organisations evolve from the first through the second and sometimes to the third of these domains. Where stakeholder values and unaligned institutional arrangements are the biggest barriers to effective progress, a transformational approach may ultimately be required to provide the direction within which traditional risk management and smaller scale initiatives can progress (Park et al. 2011; Stafford Smith et al. 2011; Gorddard et al. 2016).

The fourth (assurance process) can be applied at any stage with the level of detail depending on the issue being assured, but will often be closer to a standard checklist of questions.

An effective overall product strategy will need to address all of these four decision domains and a key objective should be to draw on common product material as much as possible to show the connections and allow smooth movement between these domains. Products need to be layered in levels of detail to match these different stages of development and accommodate the varying levels of experience and capacity within organisations. They also need to facilitate entry at any step in the process cycle, recognising that, in reality, organisations will find themselves with existing activities under way relevant to several of the steps at the same time.

-

(e)

Providing integrated access to enabling capabilities not just process/data/knowledge products

Stakeholders wanted support that integrates access to relevant process, data and knowledge products. However, they also wanted support with enabling capabilities and not just improved products and tools (see Fig. 4). These are necessary to drive adaptation action; build a sustainable capability over time, with ongoing learning and improvement; and to enable the translation to sectoral, local and individual organisational decision-making context and needs. This includes the development of formal and informal communities of practice and knowledge brokering (national, sectoral and regional/jurisdictional), building wherever possible on existing networks and capabilities, and especially with peers and policymakers, as well as experts.

3.3 Designing a national support strategy that meets user needs

The next step in co-designing a national support strategy was to review currently available products against the identified user needs. A database of Australian and international products and services was developed and products reviewed against a range of user criteria including the extent to which they incorporated leading adaptation practices, the level of ‘authority’ (e.g. legitimacy, credibility, currency, continuous improvement) and ease of use and interpretation for the intended audience (e.g. flexibility of entry and layering of detail; accessibility and integration of sources; and availability of support for translation to a decision-making context).

The summary diagnosis in the Australian context was that while there are many products and tools, the effort has been fragmented, with little guidance about which products are most relevant to particular purposes and a lack of perceived authority, consistency, enabling support, ongoing resourcing and sustained learning and enhancement. There were many interesting products and tools that support a component of the overall adaptation process, but these were not clearly positioned in the broader process. This fragmentation has led to user confusion, duplication of effort and limited product support and improvement. Very few products incorporated emerging leading adaptation practices. Several had been withdrawn or were not effectively supported or maintained, because they relied on temporary funding or resourcing.

Internationally, there were a number of interesting ‘exemplar’ products which incorporated many of the desirable characteristics (e.g. the UKCIP Wizard; ICLEI Canada’s Building Adaptive and Resilient Communities program/products and several other ICLEI products for local government in other jurisdictions; the Climate-Adapt portal in the European Union; and the NOAA Climate Resilience Toolkit in the USA). While very useful insights were gained from such products, it was also clear that the products could not be applied directly to another jurisdictional context without significant change and customisation.

Overall, it was concluded that significant improvements were possible, the core issue being how to meet diverse needs authoritatively, while avoiding unnecessary fragmentation; and how to build on promising but incomplete national and sub-national initiatives. We then co-developed with stakeholders five principles for a more systematic national adaptation decision support strategy.

-

1.

Consolidate national effort into core authoritative adaptation platforms and products, with common and linked process guidance and data sources, and a commitment to ongoing support and continuous improvement. The authority of such products, building on existing products and experience wherever possible, will be enhanced by an open and collaborative development process, including endorsement by users, stakeholders and experts. The platform should incorporate direct ‘process stage’ links to trusted data, methods and models and to knowledge networks, communities of practice (including peer contacts) and case studies. Making this consolidated and authoritative activity a priority also provides a vehicle and foundation to advance the other proposed directions.

-

2.

Encourage demand-driven sector/locational/jurisdictional platforms and products that build on and extend the core national products to meet the many genuine differentiated needs. Such products, sponsored by the relevant stakeholder interests according to need, should include typical adaptation risk profiles, response options and examples for that sector/location. These products should progressively ensure alignment with the authoritative national products where the need is common.

-

3.

Ensure these platforms and products are progressively quality assured including incorporation of key identified user needs: leading adaptation practices; authoritative adaptation process, data and model sources; and the flexibilities, layering and integration sought by users (see Table 1 )

-

4.

Complement the platform and product development process with ongoing enablers, and especially communities of practice and knowledge brokering. The proposed collaborative approaches to national and sub-national product development can also be used to catalyse and create the necessary enabling capabilities to get full value from products and sustained capability and continuous improvement over time. Communities of practice can be developed to contribute to product development, enhancement and improvement and help sponsor knowledge brokering and sharing.

-

5.

Catalyse the national strategy initially through government leadership and coordination, but with progressively increasing ‘across sector’ stakeholder support, ownership and resourcing—development of a strategic coalition. Such a national cross-sector strategic coalition can provide continuity of support beyond political cycles and can also facilitate the many potential synergies between each of the above strategic directions, platforms and products. For example, significant value was seen in development of an accessible repository of validated products and sources. Currently, most stakeholders are understandably not even aware of the full range of activities currently under way. A positive sign for a potential strategic coalition across and within sectors is the growing interest and activity in the private and community sectors to complement efforts in the public sector.

4 Discussion and conclusions

4.1 Implications of the findings and follow-up activities

There is limited consolidation of experience in the numerous adaptation decision support initiatives within Australia. The level of adaptation action and decision-making confidence is generally low and patchy, and good adaptation practice is not yet effectively embedded in normal business processes. End-users are often unsure as to the most appropriate adaptation decision-making processes and data for their context.

However, practical and positive foundations now exist to address these issues. In all sectors, we have identified common and highly differentiated climate adaptation support needs from end-user perspectives. We provide frameworks to support further understanding of those needs and five principles for developing national and sub-national support products and services.

Recent developments in Australia provide the opportunity to progress some of these strategies, though it is clear that the ideal solution is still evolving. A new climate information platform, projections and tools have been released which are more focussed on practical usage within the decision-making context than previously (CSIRO and BOM 2017); the relevant federal government department has been investigating how good practice adaptation processes might be incorporated into enhanced cross-sector national guidance; and as an example of this, the department has funded the development of a national coastal adaptation product CoastAdapt (NCCARF 2017b). CoastAdapt was developed in a way that is consistent with the findings and principles from this study, including widespread stakeholder engagement (Palutikof et al. 2018).

Challenges remain to extend this promising start with resources for ongoing product support and improvement and to gain increasing alignment with other sectoral and jurisdictional products. National governments can play an essential role in overcoming the current adaptation knowledge and experience deficit—a form of market failure in such a new decision-making domain. This deficit requires continuity in resourcing and support until the approaches become self-generating and incorporated into a new ‘business as usual’.

4.2 Application internationally

We reviewed a large number of international products and services, as well as more general reports on adaptation support in various jurisdictions (e.g. UKCIP 2011; European Commission 2014, 2015; National Research Council 2009; Moss 2016), and held discussions with several national and international agencies with relevant mandates and experience. It was noted that the US (NAF 2017), Canada (NRCAN 2017), UK (UKCIP 2011) and the EC (European Commission 2015) have also each at various times developed some form of national forum or mechanism to facilitate more coordinated support for adaptation. While no equivalent to our integrated and cross-scale/sector synthesis of user needs, leading practices, available products and strategic solutions was discovered, we did find that similar issues are arising elsewhere, including the question of how to address excessive fragmentation of effort and gain greater end-user confidence and traction.

The overall conclusions for Australia and internationally are that

-

Drawing on the remarkable growth in research and practical experience, there is now a real opportunity to provide decision-makers with improved adaptation guidance and more confidence. There has been a time to experiment, and now, with the confidence from growing experience, is a time to consolidate: in this case towards a smaller number of national (or international) initiatives, incorporating leading practices, collaboratively developed, with sustained delivery, support and improvement, and building wherever possible on useful current support products and services.

-

The co-developed frameworks and principles we have presented can help in the understanding and analysis of both common and differentiated needs.

-

With national leadership and more coordinated effort, it is feasible to more efficiently develop core products and enabling services to meet the common needs, including leading practices. This allows scarce stakeholder resources to focus on their own differentiated sector and locational needs and products. Indeed, it should be recognised that for most decision-makers, the real confidence to build adaptation into the way of doing business will only eventuate when translated into their own business language and processes.

-

Such approaches to support could materially accelerate the movement to adaptation action, especially when combined with use of the identified leading practices, most of which aim to accelerate the ability to move more quickly through the steps in the adaptation action and learning cycle.

-

Continuous learning is critical and a more consolidated approach to product development and support provides a much more effective base for capturing and disseminating emerging good practices.

The timing for a more systematic and coordinated approach is right. There is enough experience to deliver relevant and credible decision support that can be a key to embedding climate adaptation response into the way business is done. Though solutions clearly need to be tailored to reflect each country’s and jurisdiction’s characteristics and starting point (including especially the extent to which they already have nationally authoritative product sets), it seems that the Australian experience and findings resonate with the international experience, providing opportunity for mutual learning and contribution.

References

AGO (2006) Climate change impacts and risk management: a guide for business and government. Australian Greenhouse Office, Department of Environment and Heritage, Canberra

Agrawala S, Carraro M, Kingsmill N, Lanzi E, Mullan M, Prudent-Richard G (2011) Private sector engagement in adaptation to climate change: approaches to managing climate risks. OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 39, OECD Publishing

Bisaro A, Swart R, Hinkel J (2016) Frontiers of solution-oriented adaptation research. Reg Environ Chang 16:123–136

Bours D, McGinn C, Pringle P (2014) Monitoring and evaluation for climate change adaptation and resilience: a synthesis of tools, frameworks and approaches, 2nd edn. SEA Change CoP and UKCIP, Phnom Penh & Oxford

Bours D, McGinn C, Pringle P (2015) Editors’ notes. N Dir Eval 2015:1–12

Brown A, Gawith M, Lonsdale K, Pringle P (2011) Managing adaptation: linking theory and practice. UK Climate Impacts Programme, Oxford

CSIRO (2017) Climate Adaptation Flagship, CSIRO. https://research.csiro.au/climate/introduction/history-of-climate-adaptation-research-in-csiro/. Accessed 19 April 2017

CSIRO and BOM (2017) Climate change in Australia. CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology, Melbourne. https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au/en/ Accessed 19 April 2017

de Boer J, Wardekker JA, van der Sluijs JP (2010) Frame-based guide to situated decision-making on climate change. Glob Environ Chang Hum Policy Dimens 20:502–510

Dessai S, van de Sluijs J (2007) Uncertainty and climate change adaptation: a scoping study. Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, Utrecht

ENA (2017) Climate change adaptation: climate risk and resilience manual. Energy Networks Australia http://www.energynetworks.com.au/climate-change-adaptation Accessed 19 April 2017

European Commission (2014) Adaptation platforms in Europe: addressing challenges and sharing lessons. Report of workshop 7–8 November 2013, Vienna, EC CIRCLE 2 Initiative. http://www.circle-era.eu/np4/%7B$clientServletPath%7D/?newsId=668&fileName=2014.02.11_Adaptation_Platforms_in_Europ.pdf. Accessed 19 April 2017

European Commission (2015) Circle 2. Project funded by European Commission Seventh Framework Programme, European Commission, Brussels. http://www.circle-era.eu/np4/home.html. Accessed 19 April 2017

Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L (eds) (2011) Climate change adaptation in developed nations: from theory to practice. Springer

Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L, Paterson J (2011) A systematic review of observed climate change adaptation in developed nations: a letter. Clim Chang 106:327–336

Fuenfgeld H, Webb RJ, McEvoy D (2012) The significance of adaptation framing in local and regional adaptation planning initiatives in Australia. In: Otto-Zimmerman K (ed) Resilient Cities 2: cities and adaptation to climate change. Proceedings of the Global Forum 2011, ICLEI, Springer, p 283−293

Gorddard R, Colloff MJ, Wise RM, Ware D, Dunlop M (2016) Values, rules and knowledge: adaptation as change in the decision context. Environ Sci Policy 57:60–69

Griffith University (2013) Coastal hazard adaptation options: a compendium for Queensland Coastal Councils. Griffith University Centre for Coastal Management and GHD Pty Ltd. https://www.townsville.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/7035/Coastal_Hazard_Adaptation_Options.pdf. Accessed 19 April 2017

Haasnoot M, Kwakkel JH, Walker WE, ter Maat J (2013) Dynamic adaptive policy pathways: a method for crafting robust decisions for a deeply uncertain world. Glob Environ Chang 23:485–498

Hinkel J, Bisaro A (2016) Methodological choices in solution-oriented adaptation research: a diagnostic framework. Reg Environ Chang 16:7–20

Hinkel J, Bisaro A, Swart R (2016) Toward a diagnostic adaptation science. Reg Environ Chang 16:1–5

IPCC (2014a) Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change on Adaptation to the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC

IPCC (2014b) Chapter 25. Australasia. In: Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, Contribution of Working Group II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change on Adaptation to the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC

IPCC (2014c) Chapter 2. Foundations for decision making. In: Climate Change 2014: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, Contribution of Working Group II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change on Adaptation to the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC

Jones RN, Preston BL (2011) Adaptation and risk management. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 2(2):296–308

Maru YT, Stafford Smith M (2014) Reframing adaptation pathways. Glob Environ Chang 28:322–324

Moser SC, Ekstrom JA (2010) A framework to diagnose barriers to climate change adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(51):22026–22031

Moss RH (2016) Assessing decision support systems and levels of confidence to narrow the climate information “usability gap”. Clim Chang 135:143–155

NAF (2017) National Adaptation Forum website. US National Adaptation Forum. http://www.nationaladaptationforum.org/. Accessed 19 April 2017

National Research Council (2009) Informing decisions in a changing climate. Panel on Strategies and Methods for Climate-Related Decision Support, Committee on the Human Dimensions of Global Change, Division of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Education. The National Academies Press: Washington DC

NCCARF (2013) Adaptation good practices project. National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast, Queensland. http://www.nccarf.edu.au/localgov/map. Accessed 19 April 2017

NCCARF (2017a) National climate change adaptation research facility website. National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast, Queensland. http://www.nccarf.edu.au/. Accessed 19 April 2017

NCCARF (2017b) CoastAdapt. National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast, Queensland. https://coastadapt.com.au/. Accessed 19 April 2017

NRCAN (2017) Adaptation platform. Natural Resources Canada. http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/environment/impacts-adaptation/adaptation-platform/10027. Accessed 19 April 2017

OECD (2009) Integrating climate change adaptation into development co-operation: policy guidance. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris

Pahl-Wostl C (2009) A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob Environ Chang 19:354–365

Pahl-Wostl C, Giupponi C, Richards K, Binder C, de Sherbinin A, Sprinz D, Toonen T, van Bers C (2013) Transition towards a new global change science: requirements for methodologies, methods, data and knowledge. Environ Sci Policy 28:36–47

Palutikof JP, Rissik D, Webb S, Tonmoy FN, Boulter SL, Leitch AM, Perez Vidaurre AC, Campbell MC (2018) CoastAdapt: an adaptation decision support framework for Australia's coastal managers. Clim Chang (accepted, this special issue)

Park SE, Marshall NA, Jakku E, Dowd AM, Howden SM, Mendham E, Fleming A (2011) Informing adaptation responses to climate change through theories of transformation. Glob Environ Chang 22(1):115–126

Rissik D, Smith M (2016) Investing through an adaptation lens: a practical guide for investors. The Investor Group on Climate Change, Australia

Rissik D, Boulter S, Doer V, Marshall N, Hobday A, Lim-Camacho L (2014) The NRM Adaptation Checklist: supporting climate adaptation planning and decision-making for regional NRM. CSIRO and NCCARF, Australia

Stafford Smith M, Horrocks L, Harvey A, Hamilton C (2011) Rethinking adaptation for a 4°C world. Philos Trans R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci 369(1934):196–216

UKCIP (2011) Making progress: UKCIP and adaptation in the UK. UK Climate Impacts Programme, Oxford

UNFCCC (2017) Adaptation private sector initiative: climate change adaptation in the private sector. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. http://unfccc.int/adaptation/nairobi_work_programme/private_sector_initiative/items/4623.php. Accessed 19 April 2017

Valls-Donderis P, Ray D, Peace A, Stewart A, Lawrence A, Galiana F (2014) Participatory development of decision support systems: which features of the process lead to improved uptake and better outcomes? Scand J For Res 29:71–83

Webb RJ, Beh J-L (2013) Leading adaptation practices and support strategies for Australia: an international and Australian review of products and tools. Report for the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast, p120. https://www.nccarf.edu.au/sites/default/files/attached_files_publ.ications/Webb_2013_Leading_adaptation_practices_support.pdf. Accessed 1 August 2017

Webb RJ, McKellar R, Kay R (2013) Climate change adaptation in Australia: experience, challenges and capacity building. Aust J Environ Manag 20(4):320–337

Webb RJ, Petheram L, Weiske P (2014) Climate adaptation decision support strategies: developing a national agenda. Report for Commonwealth Department for the Environment and the CSIRO, Canberra, ACT. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319165028_Climate_Adaptation_Decision_Support_Strategies_Developing_a_National_Agenda_LAPS_2_Final_Report_-_5_June_2014. Accessed 15 Dec 2017

Willows RI, Connell RK (2003) Climate adaptation: risk, uncertainty and decision making. UK Climate Impacts Programme, Oxford

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the contribution of the stakeholders to the development of findings and conclusions.

Funding

The Leading Adaptation Practices and Support program was funded by the NCCARF (first phase) and the federal Department of Environment and CSIRO (second phase).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of a Special Issue on ‘Decision Support Tools for Climate Change Adaptation’ edited by Jean Palutikof, Roger Street and Edward Gardiner.

Electronic supplementary material

Online resource 1

(DOCX 46.3kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Webb, R., Rissik, D., Petheram, L. et al. Co-designing adaptation decision support: meeting common and differentiated needs. Climatic Change 153, 569–585 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2165-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2165-7