Abstract

Sustainable water management in a changing environment full of uncertainty is profoundly challenging. To deal with these uncertainties, dynamic adaptive policies that can be changed over time are suggested. This paper presents a model-driven approach supporting the development of promising adaptation pathways, and illustrates the approach using a hypothetical case. We use robust optimization over uncertainties related to climate change, land use, cause-effect relations, and policy efficacy, to identify the most promising pathways. For this purpose, we generate an ensemble of possible futures and evaluate candidate pathways over this ensemble using an Integrated Assessment Meta Model. We understand ‘most promising’ in terms of the robustness of the performance of the candidate pathways on multiple objectives, and use a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm to find the set of most promising pathways. This results in an adaptation map showing the set of most promising adaptation pathways and options for transferring from one pathway to another. Given the pathways and signposts, decision-makers can make an informed decision on a dynamic adaptive plan in a changing environment that is able to achieve their intended objectives despite the myriad of uncertainties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Nowadays, decision-makers face deep uncertainties from a myriad of external factors (e.g., climate change, population growth, new technologies, economic developments) and their impacts. Traditionally, decision-makers in most policy domains, such as water management, transportation, spatial planning, and business planning, assume that the future can be predicted. However, if the future turns out to be different from the hypothesized futures, the plan is likely to fail. McInerney et al. (2012) liken this to “dancing on the tip of a needle”. It has been argued extensively that the assumption that the future can be predicted accurately does not hold. The accuracy of forecasts is intrinsically limited by fundamental irreducible uncertainties due to limits in the knowledge base, inherent randomness, chaotic dynamics, non-stationarity, and future actions by decision-makers (Hallegatte et al. 2012; Kwakkel et al. 2010b; Dessai et al. 2009; Lempert et al. 2003; Milly et al. 2008). Also, societal perspectives and preferences may change over time, including stakeholders’ interests and their evaluation of plans (for historical examples, see van der Brugge et al. 2005). To cope with this intrinsic limit to the predictability of the future, the challenge is to develop plans whose performance is insensitive to the resolution of the various uncertainties (Dessai et al. 2009).

An emerging planning paradigm aims at achieving such insensitive plans through designing plans that can be adapted over time in response to how the future actually turns out. This paradigm holds that, in light of the deep uncertainties, one needs to design dynamic adaptive plans (Albrechts 2004; Swanson et al. 2010; Walker et al. 2001; Hallegatte 2009). Central to this paradigm is that the idea of finding a static optimal plan is replaced by finding a dynamically robust plan. That is, it aims at finding a plan that will be successful in a wide variety of plausible futures, through the ability to adapt the plan dynamically over time in response to how the future unfolds. This planning paradigm, in one form or another, has been receiving increasing attention in various policy domains. Dynamically robust plans are being developed for water management in New York City (Rosenzweig et al. 2011), New Zealand (Lawrence and Manning 2012), the Thames Estuary (Reeder and Ranger Available online), the Colorado River (Groves et al. 2012), and the Rhine Delta (Jeuken and Reeder 2011). Dynamic adaptive plans have also been developed for other policy domains (for examples, see Swanson and Bhadwal 2009; Walker et al. 2010).

One major challenge for this paradigm is how to offer support for the design of such dynamic adaptive plans (Walker et al. 2010; Lempert et al. 2009; Lempert and Schlesinger 2000). The paradigm implies that there is a practically infinite number of plausible futures that should be considered (Lempert et al. 2009). Moreover, there is a large number of plausible actions that could be taken to handle these futures. The analysis of plausible actions is further complicated by the fact that plans should be adapted over time, necessitating analyzing scenarios over time, or ‘transient scenarios’ (Haasnoot et al. 2012), including a staged decision process. Only in this way can the interplay between an unfolding scenario and the dynamic adaptation of a plan over time be explored. Finally, the plan need to take into consideration a wide array of perspectives from different stakeholders, both now and in the future. That is, the adaptive plan should be robust with respect to the future, but also be socially robust (Offermans 2012). Analyzing climate adaptation in this way results in the ‘curse of dimensionality’ and is severely limited in practice by the necessary computational burden (Webster et al. 2011).

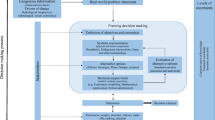

In this paper, we consider one approach that exemplifies the new planning paradigm ̶ dynamic adaptive policy pathways (Haasnoot et al. 2013) ̶ and show how this approach can be supported computationally. Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways (DAPP) combines two bodies of literature on planning under uncertainty: work on adaptive policymaking (Walker et al. 2001; Kwakkel et al. 2010a; Hamarat et al. 2013); and work on adaptation tipping points and policy pathways (Kwadijk et al. 2010; Haasnoot et al. 2012; Offermans 2012). In DAPP, a plan is conceptualized as a series of actions taken over time. In order to come to a good plan, it is necessary to first identify candidate policy actions and their adaptation tipping points. An adaptation tipping point is the condition under which a given policy action no longer meets its objectives. The point in time at which this happens ̶ the sell-by date ̶ is scenario dependent. In light of an analysis of the sell-by dates of various policy actions, concatenations of options, or policy pathways, can be specified where a new policy option is activated once its predecessor is no longer able to meet the definition of success. Typically, there is a portfolio of pathways that decision-makers would like to keep open for the future. This adaptation map forms the basis for the plan. Fig. 1 shows an example of such a map. For a more detailed elaboration on DAPP, see Haasnoot et al. (2013).

An example of an Adaptation Pathways map (left) and a scorecard presenting the costs and benefits of the 9 possible pathways presented in the map. In the map, starting from the current situation, targets begin to be missed after four years. Following the grey lines of the current plan, one can see that there are four options. Actions A and D should be able to achieve the targets for the next 100 years in all climate scenarios. If Action B is chosen after the first four years, a tipping point is reached within about five years; a shift to one of the other three actions will then be needed to achieve the targets (follow the orange lines). If Action C is chosen after the first four years, a shift to Action A, B, or D will be needed after approximately 85 years in the worst case scenario (follow the solid green lines). In all other scenarios, the targets will be achieved for the next 100 years (the dashed green line). The colors in the scorecard refer to the actions: a (red), b (orange), c (green), and d (blue)

There are two challenges for DAPP: (i) identifying the most promising sequences of actions (those that are robust in some sense), taking into account a very large variety of plausible transient scenarios; and (ii) the combinatoric problem arising out of the multiplicity of ways in which actions can be sequenced over time, and the rules to be used to govern when new actions are to be triggered.

In order to address both challenges, we use a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for robust optimization. This type of algorithm is ideally suited for solving constrained non-linear problems with high dimensional decision spaces (Kasprzyk et al. 2013; Coello Coello et al. 2007; Reed et al. 2013). To support the identification of the most promising sequences of actions, we use a computational scenario-based approach (Lempert and Schlesinger 2000; Morgan and Dowlatabadi 1996). We evaluate candidate pathways over an ensemble of possible futures, and assess their robustness. This ensemble covers the space of uncertainties about the future (using climate and socio-economic scenarios), uncertainties about alternative formulations for aspects of the model, and uncertainties about the efficacy of policy actions, and is generated using Exploratory Modeling and Analysis (EMA) (Bankes 1993; Lempert et al. 2003; Bankes et al. 2013). We assess the robustness of candidate pathways on multiple independent objectives, avoiding the need to make assumptions about decision-maker trade-off preferences. So, through multi-objective robust optimization, we are able to resolve the challenge of finding the most robust adaptive policy pathways.

To illustrate our approach, we use a hypothetical case inspired by a river reach in the Rhine delta of the Netherlands. As most existing computational hydrological impact models demand too much computing time for simulating the dynamics of adaptation pathways (de Lange et al. 2014; Haasnoot et al. 2014), we use an Integrated Assessment Meta-Model (IAMM) based on more complex detailed models (Haasnoot et al. 2012).

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we provide additional details on multi-objective robust optimization. Section 3 contains the application of the method to the hypothetical case. Section 4 discusses the results. Section 5 presents our conclusions, including suggestions for future research.

2 Computational support for DAPP

Optimization is a popular tool for supporting decision-making. Optimization is used for identifying the best solution among a set of possible alternatives without violating the given constraints. Under deep uncertainty, such an optimum solution usually does not exist (Bankes 2011; Rosenhead et al. 1973). One way of addressing this problem is to use optimization anyhow, but subsequently test the robustness of the identified solution through some form of sensitivity analysis. In a recent paper, Kasprzyk et al. (2013) present an approach that is very similar in spirit to the work reported in this paper. They use optimization to find a set of candidate solutions, which is subsequently assessed on its robustness using EMA. In contrast to Kasprzyk et al. (2013), we pursue a pro-active solution to the problem by using robust optimization. Robust optimization methods aim at finding optimal outcomes in the presence of uncertainty about input parameters that are not overly sensitive to any specific realization of the uncertainties (Ben-Tal and Nemirovski 1998, 2000; Bertsimas and Sim 2004; Bai et al. 1997; Kouvalis and Yu 1997). In robust optimization, the uncertainty that exists about the outcomes of interest is described through a set of scenarios (Mulvey et al. 1995). Robustness is then defined over this set of scenarios. In this way, robust optimization differs from worst-case formulations (Wald 1945), which can produce very costly and conservative solutions (Mulvey et al. 1995).

The use of robust optimization for supporting the design of dynamic adaptive policy pathways requires the assessment of candidate adaptation pathways over an ensemble of transient scenarios about the future and additional uncertainties related to diverse ways of modeling the system and the efficacy of candidate policy actions. A method that can be used to facilitate this analytical process is Exploratory Modeling and Analysis. EMA is a research methodology that uses computational experiments to analyze complex and uncertain systems (Bankes 1993; Bankes et al. 2013). The basic idea of EMA is to develop an ensemble of models that capture different sets of assumptions about the world and to explore the behavior of this ensemble through computational experiments. A single model run drawn from this set of plausible models provides a computational experiment that reveals how the world would behave if the assumptions encapsulated in this specific model were correct. Through conducting many computational experiments in a structured way, one can explore and analyze the implications of the various alternative assumptions.

Given the performance of a candidate adaptation pathway over an ensemble of scenarios, the next step is to operationalize robustness. Robustness can be operationalized in a wide variety of ways (see e.g. Rosenhead et al. 1973; Wald 1945; Savage 1951; Simon 1955; Kouvalis and Yu 1997). In the EMA literature, robustness has been defined as the first order derivative of the objective function (McInerney et al. 2012); as a reasonable performance over a wide range of plausible futures (Lempert and Collins 2007); relative, based on regret (Lempert et al. 2003); and as sacrificing a small amount of optimal performance in order to be less sensitive to violated assumptions (Lempert and Collins 2007). This last definition shares a family resemblance with the local robustness model employed in Info-Gap Decision Theory (Ben Haim 2001).

A distinction can be made between single-objective optimization and multi-objective optimization. In the single objective optimization case, multiple objectives are combined, drawing on Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis approaches (Deb et al. 2002). In contrast, in the multi-objective case, one aims at making the trade-offs among the different objectives explicit through the identification of the set of non-dominated solutions. A solution is non-dominated if the performance of this solution is not exceeded on all objectives by any other solution (Reed et al. 2013). The set of non-dominated solutions makes the various trade-offs or conflicts among the different objectives explicit, offering a form of posterior decision support (Coello Coello et al. 2007).

Classic optimization approaches can be adapted to solve multi-objective optimization problems by turning the problem into a single-objective problem, resulting in finding a single Pareto optimal solution at a time. More effective, however, is the use of evolutionary algorithms. Evolutionary algorithms use a population of solutions. This population can be evolved in such a way that it maintains diversity, while continually moving towards the Pareto frontier. In this way, multiple Pareto front solutions can be found in a single run of the algorithm (Deb et al. 2002). Currently, a wide variety of alternative multi-objective evolutionary algorithms are available for solving multi-objective optimization problems. In this paper, we use the Nondominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm-II (NSGA-II) (Deb et al. 2002). This is a well-known algorithm that has been applied in a wide range of optimization problems.

3 Application: The waas case

3.1 Background on the waas case

To illustrate the outlined approach, we use a hypothetical case, called ‘the Waas’. The case is based on the Waal, a river reach in the Rhine delta of the Netherlands. The river and floodplain are highly schematized, but have realistic characteristics. The river is bound by embankments, and the floodplain is separated into five dike rings. A large city is situated on higher grounds in the southeast part. Smaller villages exist in the remaining area, including greenhouses, industry, conservation areas, and pastures. In the future, climate change and socio-economic developments may increase the pressure on the available space and potential future damages, so actions are needed. We use an IAMM (for details, see Haasnoot et al. 2012) implemented in PCRaster (van Deursen 1995). The model was checked for internal consistency and plausibility of the outcomes by expert judgment.

The analysis takes into account uncertainties related to climate change, land use, system characteristics, and the effects of policy actions (Table 1). The effects of different climate change scenarios are considered through changes in river discharge (see Haasnoot et al. 2012 for details). Uncertainties in the cause-effect relations for the fragility of dikes and economic damage functions are taken into account by putting a bandwidth of plus and minus ten percent around the default values; for each experiment, we randomly pick a value in this interval and update the default values accordingly.

Table 2 provides an overview of the 20 policy options that are explored. The actions include flood prevention measures such as heightening the dikes, strengthening the dikes, and giving room for the river, and flood mitigation actions such as upstream collaboration, evacuation preparation, alarms, additional embankments around cities, houses on stilts, etc. The actions can be combined into sequences: adaptation pathways. In order to govern the activation of the next action on a pathway, we use a simple rule-based system. Every five years, the results of the system in terms of causalities and economic damages are evaluated and classified into no event, small event, large event, and extreme event. We activate a new action if, in the previous five years, an event of the pre-specified level is encountered. The choice for using a step size of five years is motivated by runtime constraints and prior experience with this particular case.

3.2 Formulating the optimization problem

We can now formulate the optimization problem that we are trying to solve.

Minimize F(l p,r ) = (f costs , f casualties , f damage )

where \( \begin{array}{ll}{\mathrm{l}}_{p, r}=\left[{p}_1,\ {p}_2,{p}_3,{r}_1,{r}_2\right]\hfill & \forall p\in P;\ \forall r\in R\hfill \\ {}{f}_i\left({y}_i\right) = {\overset{\sim }{y}}_i \cdot p \left( IQR\left({y}_i\right)+1\right)\hfill & \hfill \\ {} i\in \left\{ costs,\ casualties,\ damages\right\}\hfill & \hfill \end{array} \)

subject to \( \begin{array}{l}{c}_{damage}:{\tilde{y}}_{damage}\ \le 50000\hfill \\ {}{c}_{c asualties}:{\tilde{y}}_{c asualties}\ \le 1000\hfill \end{array} \)

where l p,r denotes a policy pathway, p m is a policy action, P is the set of policy actions as specified in Table 2, r n is a rule, R is the set of rules as discussed in the previous section, y i is the set of outcomes for outcome i across a set of scenarios, \( {\overset{\sim }{y}}_i \) is the median value for y i , and IQR is the interquartile range for y i . So, each of the three outcomes of interest (costs, casualties, and damages) is defined as the median value multiplied by the interquartile distance plus one. That is, we try to simultaneously minimize the median outcome as well as the dispersion around the median. This is very similar to risk discounting (Rosenhead et al. 1973). The minimization problem is subject to two constraints. For flood damage, the median value of the sum total of flood damage over 100 years should not exceed 50,000 million Euro. For casualties, the median value for the sum total of casualties over 100 years should not exceed 1,000 people.

The robustness metric requires evaluating each candidate pathway using many computational experiments. We used the same set of experiments for all evaluations. If we were to regenerate experiments for every iteration of the algorithm, the performance of the candidate solutions could vary slightly from one generation to the next, introducing the additional problem of optimizing noisy performance indicators. We return to this point in the discussion. An analysis of 10 randomly generated pathways revealed that the robustness metric for the three indicators stabilized at around 150 experiments. Therefore, in what we present below, we use 150 experiments, generated using Latin Hypercube sampling.

We implemented the algorithm in Python (van Rossum 1995), using DEAP, a library for genetic algorithms (Fortin et al. 2012). We ran the optimization for 50 generations, with a population size of 50, a mutation rate of 0.05, and a crossover rate of 0.8. The assessment of convergence was based on tracking the changes to the set of non-dominated solutions over the generations. Runtime was roughly one week on a six core Intel Xeon workstation with hyper threading. To assess the robustness of the results to randomization, we ran the optimization problem three times using different random seeds. The resulting set of non-dominated solutions was identical for these three runs. The population size was established by experimenting with different population sizes in the range 10–100. A population size of 50 appeared to offer a balance between computational time and the need to maintain diversity.

3.3 Results

Figure 2 shows the resulting scores for the non-dominated pathways. It gives insight into the trade-offs among the best solutions. In total, we identified 74 unique non-dominated pathways. However, for a substantial number of these pathways, their resulting scores on the three criteria are identical, and hence they do not show up clearly in the figure. Remember that we aim to minimize the three outcomes, so the lower the score, the better. As can be seen, low scores on flood damage robustness and casualty robustness co-occur with high scores on cost robustness. Conversely, high scores on both flood damage and casualties co-occur with low scores on cost robustness. It appears however, that there are a few solutions where a relatively low score on cost robustness can be combined with modest values on casualty and flood damage robustness. There is no strong trade-off between damage and casualties: high values on one correspond to high values on the other.

Figure 3 shows the resulting Adaptation Pathways Map and associated scorecard. To arrive at this figure, we took several steps. First, in case of several families of actions, it is not possible to scale back; for example, it is not possible to lower a dike. If a less severe action is preceded by a more severe action, the less severe action is ignored. Second, we analyzed the timing of the adaptation tipping points. This showed that there are pathways that contain actions that are hardly ever or never reached. We removed these actions from the pathway. Third, we ignored the difference in adaptation tipping points arising from differences in rules. Fourth, we used the normalized values for the robustness scores, as shown in Fig. 2. These steps produced 11 unique pathways.

It is worth noting that this set of pathways contains either very expensive solutions (the dike raising pathways) that are also very effective in reducing casualties and damage, or very cheap solutions with more severe casualties and damages. Moreover, we see that the resulting pathways contain at most two solutions. We suggest that this is primarily due to the robustness metric. Remember, we searched for solutions that have both a low median value as well as a low interquartile distance. This implies that we have searched for solutions where the costs are quite similar across the set of 15 scenarios. For costs, this is a debatable way of defining robustness. A major argument for adaptation pathways is that it can potentially reduce costs. That is, the distribution of costs for an attractive flexible solution across a range of scenarios is skewed towards the lower side. This negative skewness is not considered by the robustness metric we used.

4 Discussion

The aim of using multi-objective robust optimization in this paper is not to replace decision-makers. Rather, we have used it as a decision support mechanism − a technique to search in a directed way for a diverse set of robust pathways. In this way, the space of candidate pathways is pruned substantially. By focusing on robustness, the multiplicity of futures spanned by the various uncertainties is also addressed. The final product of this approach is, purposefully, not a single best solution, but a map that shows the diverse set of robust candidate pathways. The actual decision-making process can then focus on translating this adaptation map into a plan of action ̶ that is, deciding which pathway or set of pathways to keep open to future developments, and what that implies for short-term actions and the establishment of a monitoring system.

We have chosen one particular way of defining robustness ̶ in the form of a satisficing criterion. Other definitions of robustness might result in a different set of Pareto optimal robust candidate pathways. This resulted in extreme policy actions, which are quite costly and very effective. However, decision-makers might find other actions with lower costs and slightly less effective, which are now dominated, acceptable as well. It would be interesting to explore the extent to which the choice of robustness operationalization affects the set of identified solutions.

We used NSGA-II for solving the multi-objective optimization problem. This is one of the best-known algorithms for solving these problems. However, in an extensive comparison of NSGA-II with more recent and more sophisticated algorithms, it was shown that NSGA-II can perform poorly in particular classes of problems (Reed et al. 2013). The approach that we have presented in this paper does not necessarily rely on NSGA-II. Other more modern algorithms can be used instead of NSGA-II, which might have even better performance characteristics. Of particular interest are auto-adaptive algorithms such as Borg (Hadka and Reed 2013), which tailor the various parameters that control the behavior of the algorithm to the specific characteristics of the problem (Reed et al. 2013).

To simplify the optimization problem, we used the same test set of 150 scenarios to assess the robustness of the candidate pathways. The advantage of this approach is that it is straightforward to implement. There are, however, several downsides to this approach. First, the value of our robustness metric depends on the 150 scenarios. If a different set of scenarios were used, the scores on the metric might be slightly different, potentially resulting in changes to the composition of solutions on the Pareto front. Although we did not find any change in our replications using different random seeds, it is theoretically possible. Second, you might be wasting computational resources by calculating the performance over 150 scenarios. Ideally, you want to dedicate computational effort to calculating the robustness metric in proportion to how promising a given candidate pathway is. That is, the more promising a solution appears to be, the more accurate you want to know its score on the robustness metric.

A crucial component of an adaptation pathway is the set of rules that govern when the next action on the pathway should be activated. Noise arising out of natural variability can obfuscate this signal, making it harder to detect. For example, the natural variability in river runoff can be so large that an underlying changing trend is hard to detect (Diermanse et al. 2010). The more ambiguous the signposts are, the more prone an adaptive plan is to produce poor results (Lempert et al. 1996). The selection of good indicators that can be used as signposts is thus of crucial importance to the proper functioning of an adaptive plan.

In the Waas case, we considered only objectives directly related to flooding − casualties, economic damage, and costs. However, the actors involved in such decisions in the real world also care about other indicators, including indicators for ecology, agriculture, industrial water use, and recreation. The approach we have presented can easily be extended to cover those additional criteria. However, it is likely that increasing the number and diversity of indicators will increase the required runtime, since the larger and more heterogeneous the indicators, the more possible solutions there can be on the Pareto frontier.

A limitation of the approach we have outlined is that it relies on a fast integrated model of the system of interest. In our case, the Waas model was readily available and had a relatively fast runtime. But even with this fast hydrological model, performing the optimization on a single machine took one week. Reducing the time for performing the optimization can be achieved by moving from a single machine to a high performance cluster. But, even in that case, the runtime of the model should be kept as low as possible. The problem then becomes one of finding the right balance between accuracy and runtime. Alternatively, through the smart selection of scenarios, a substantial gain in runtime might be possible.

The approach presented above aimed at finding promising pathways in the presence of a large variety of possible actions and a wide range of different uncertainties. The approach has been able to deliver on this. However, as noted, the way in which robustness is defined, in particular for costs, has a substantial influence on the pathways that are identified. The added value of the approach thus hinges on the careful operationalization of robustness. For real world decision-making, the approach can help in reducing the set of candidate solutions and pathways to a manageable subset. It is envisioned that policy analysts would carry out most of the steps and involve decision-makers at selected points in the process, resulting in ‘deliberation with analysis’ (NRC 2009). Decision-maker involvement is crucial in the scoping of the problem, including the specification of the problem, the policy actionactions, the major uncertainties, and the outcomes of interest. Moreover, it can result in surprising finds. In the case presented above, actions that had been filtered out based on their individual performance turned out to be beneficial as part of a pathway.

5 Conclusions

Traditional decision-making based on predicted futures has been likened to ‘dancing on the tip of a needle’ (McInerney et al. 2012). Such plans gamble on the fact that the predictions of the future turn out to be correct. However, if there are even small deviations from these predictions, the performance of such plans can deteriorate very quickly. Dynamic adaptive planning approaches have been suggested as a way of overcoming this problem. Dynamic adaptive plans are prepared with the multiplicity of plausible futures in mind. These plans commit to short-term actions, and prepare additional actions that can be implemented if, in light of what is learned over time or how the future unfolds, these actions prove necessary. There is a clear need for approaches that can support planners and decision-makers in the development of such plans.

Our approach uses dynamic adaptive policy pathways as a way for operationalizing the dynamic adaptive planning paradigm. The need for decision support in this approach is twofold: to explore the consequences of a large ensemble of plausible futures, and to explore a wide variety of alternative policy pathways. We outlined a way of offering decision support based on the combination of EMA and multi-objective robust optimization. EMA offers support in generating a large ensemble of plausible futures and exploring the performance of candidate pathways over this ensemble. Multi-objective robust optimization helps in identifying a heterogeneous set of robust candidate pathways. We argue that the identification of promising candidate pathways is especially valuable in complex, deeply uncertain problem situations with large numbers of possible solutions that can be combined in a variety of ways.

The results of the analysis with the Waas case support the hypothesis that EMA combined with multi-objective robust optimization is useful for supporting the development of dynamic adaptive plans. Through this combination, we were able to identify a subset of most promising pathways. Moreover, some of these pathways contain solutions that had been discarded in earlier research. Adding additional constraints and identifying ‘near best’ (actions that perform almost as well as those on the Pareto front, but are much less expensive) could provide additional information for decision-making.

The use of EMA and robust optimization for decision support in developing dynamic adaptive plans, although here tailored to the specifics of dynamic adaptive policy pathways, can be used more generally. This is evidenced by related work on Robust Decision Making (Lempert and Collins 2007; Lempert et al. 2003; Lempert and Schlesinger 2000; Lempert et al. 1996; Hamarat et al. 2013) and Scenario Discovery (Groves and Lempert 2007; Bryant and Lempert 2010; Kwakkel et al. 2013), which also build on EMA. In this paper, the approach was demonstrated on a simplified “toy” case. Further work is needed. The approach should now be applied to real world cases, with a higher level of complexity. In this paper, we looked at a particular way of operationalizing robustness. Exploring the extent to which the operationalization of robustness affects the results is another important avenue for future work. Finally, we ended with an overview of the most promising pathways that together constitute the adaptation map. How to translate this map into a plan for action is another facet of the development of dynamic adaptive plans on which further research is needed.

References

Albrechts L (2004) Strategic (spatial) planning reexamined. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 31(5):743–758

Bai D, Carpenter T, Mulvey J (1997) Making a case for robust optimization models. Manag Sci 43(7):895–907

Bankes SC (1993) Exploratory Modeling for Policy Analysis. Oper Res 4(3):435–449

Bankes SC (2011) The use of complexity for policy exploration. The SAGE Handbook of Complexity and Management. SAGE Publications Ltd., London, UK

Bankes SC, Walker WE, Kwakkel JH (2013) Exploratory Modeling and Analysis. Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science, 3rd edn. Springer, Berlin, Germany

Ben Haim Y (2001) Information-Gap Decision Theory: Decision Under Severe Uncertainty. Academic, London, UK

Ben-Tal A, Nemirovski A (1998) Robust convex optimization. Math Oper Res 23(4):769–805

Ben-Tal A, Nemirovski A (2000) Robust solutions of linear programming problems contaminated with uncertain data. Math Program 88(3):411–424

Bertsimas D, Sim M (2004) The Price of Robustness. Oper Res 52(1):35–53. doi:10.1287/opre.1030.0065

Bryant BP, Lempert RJ (2010) Thinking Inside the Box: a participatory computer-assisted approach to scenario discovery. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 77(1):34–49

Coello Coello CA, Lamont GB, van Veldhuizen DA (eds) (2007) Evolutionary algorithms for solving multi-objective problems Genetic and Evolutionary Computation, 2nd edn. USA, Springer, New York

de Lange WJ, Prinsen GF, Hoogewoud JC, Veldhuizen AA, Verkaik J, Oude Essing GHP, van Walsum PEV, Delsman JR, Hunink JC, Massop HTL, Kroon T (2014) An operational, multi-scale, multi-model system for consensus-based, integrated water management and policy analysis: The Netherlands Hydrological Instrument. Environ Model Softw 59:98–108. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2014.05.009

Deb K, Pratap A, Agarwal S, Meyarivan T (2002) A Fast and Elitist Multiobjective Genetic Algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans Evol Comput 6(2):182–197

Dessai S, Hulme M, Lempert R, Pielke jr R (2009) Do We Need Better Predictions to Adapt to a Changing Climate? Eos 90(13):111–112

Diermanse F, Kwadijk JCJ, Beckers J, Crebas J (2010) Statistical trend analysis of annual maximum discharges of the Rhine and Meuse rivers. Paper presented at the BHS Third International Symposium. Managing Consequences of a Changing Global Environment, Newcastle, UK

Fortin FA, De Rainville FM, Gardner MA, Parizeau M, Gagné C (2012) DEAP: Evolutionary Algorithms Made Easy. J Mach Learn Res 2171–2175(13)

Groves DG, Fischbach JR, Bloom E, Knopman D, Keefe R (2012) Adapting to a Changing Colorado River: Making Future Water Deliveries More Reliable Through Robust Management Strategies. RAND corporation, Santa Monica, CA

Groves DG, Lempert RJ (2007) A New Analytic Method for Finding Policy-Relevant Scenarios. Glob Environ Chang 17:73–85

Haasnoot M, Kwakkel JH, Walker WE, Ter Maat J (2013) Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways: A New Method for Crafting Robust Decisions for a Deeply Uncertain World. Global Environmental Change 23 (2):485–498. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.12.006

Haasnoot M, Middelkoop H, Offermans A, van Beek E, van Deursen WPA (2012) Exploring pathways for sustainable water management in river deltas in a changing environment. Clim Chang 115(3–4):795–819. doi:10.1007/s10584-012-0444-2

Haasnoot M, Van Deursen WPA, Guillaume JHA, Kwakkel JH, van Beek E, Middelkoop H (2014) Fit for purpose? Building and evaluating a fast, integrated model for exploring water policy pathways. Environ Model Softw 60:99–120. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2014.05.020

Hadka D, Reed PM (2013) Borg: An Auto-Adaptive Many-Objective Evolutionary Computing Framework. Evol Comput 21(2):231–259

Hallegatte S (2009) Strategies to adapt to an uncertain climate change. Glob Environ Chang 19:240–247

Hallegatte S, Shah A, Lempert R, Brown C, Gill S (2012) Investment Decision Making Under Deep Uncertainty: Application to Climate Change. Bank, The World

Hamarat C, Kwakkel JH, Pruyt E (2013) Adaptive Robust Design under Deep Uncertainty. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 80(3):408–418. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2012.10.004

Jeuken A, Reeder T (2011) Short-term decision making and long-term strategies: how to adapt to uncertain climate change. Water Governance 1:29–35

Kasprzyk JR, Nataraj S, Reed PM, Lempert RJ (2013) Many objective robust decision making for complex environmental systems undergoing change. Environmental Modelling & Software:1–17. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2012.007

Kouvalis P, Yu G (1997) Robust Discrete Optimization and its application. Kluwer Academic Publisher, Dordrecht, the Netherlands

Kwadijk JCJ, Haasnoot M, Mulder JPM, Hoogvliet MMC, Jeuken ABM, van der Krogt RAA, van Oostrom NGC, Schelfhout HA, van Velzen EH, van Waveren H, de Wit MJM (2010) Using adaptation tipping points to prepare for climate change and sea level rise: a case study in the Netherlands. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 1(5):729–740. doi:10.1002/wcc.64

Kwakkel JH, Auping WL, Pruyt E (2013) Dynamic scenario discovery under deep uncertainty: the future of copper. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 80(4):789–800. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2012.09.012

Kwakkel JH, Walker WE, Marchau VAWJ (2010a) Adaptive Airport Strategic Planning. Eur J Transp Infrastruct Res 10(3):227–250

Kwakkel JH, Walker WE, Marchau VAWJ (2010b) Classifying and communicating uncertainties in model-based policy analysis. International Journal of Technology, Policy and Management 10(4):299–315. doi:10.1504/IJTPM.2010.036918

Lawrence J, Manning M (2012) Developing adaptive risk management for our changing climate; A report of workshop outcomes under an Envirolink Grant. The New Zealand Climate Change Research. Victoria University of Wellington, Institute

Lempert RJ, Collins M (2007) Managing the Risk of Uncertain Threshold Response: Comparison of Robust, Optimum, and Precautionary Approaches. Risk Anal 24(4):1009–1026

Lempert RJ, Popper S, Bankes S (2003) Shaping the Next One Hundred Years: New Methods for Quantitative. Long Term Policy Analysis, RAND, Santa Monica, CA, USA

Lempert RJ, Scheffran J, Sprinz DF (2009) Methods for Long-Term Environmental Policy Challenges. Global Environmental Politics 9(3):106–133

Lempert RJ, Schlesinger ME (2000) Robust Strategies for Abating Climate Change. Clim Chang 45(3–4):387–401

Lempert RJ, Schlesinger ME, Bankes SC (1996) When We Don't Know the Cost or the Benefits: Adaptive Strategies for Abating Climate Change. Clim Chang 33(2):235–274

McInerney D, Lempert R, Keller K (2012) What are robust strategies in the face of uncertain climate threshold responses. Climate Change 112:547–568

Milly PCD, Betancourt J, Falkenmark M, Hirsch RM, Kundzewicz ZW, Lettenmaier DP, Stouffer R (2008) Stationarity Is Dead: Whither Water Management? Science 319(5863):573–574

Morgan MG, Dowlatabadi H (1996) Learning from Integrated Assessment of Climate Change. Clim Chang 34(3–4):337–368

Mulvey J, Vanderbei RJ, Zenios SA (1995) Robust optimization of large-scale systems. Oper Res 43(2):264–281

NRC (2009) Informing Decisions in a Changing Climate. Press, National Academy

Offermans A (2012) Perspectives Method: towards socially robust river management. University of Maastricht, Maastricht, the Netherlands

Reed PM, Hadka D, Herman JD, Kasprzyk JR, Kollat JB (2013) Evolutionary multiobjective optimization in water resources: The past, present, and future. Adv Water Resour 51:438–456

Reeder T, Ranger N (Available online) How do you adapt in an uncertain world? Lessons from the Thames Estuary 2100 project. World Resources Report. Washington DC

Rosenhead J, Elton M, Gupta SK (1973) Robustness and Optimality as Criteria for Strategic Decisions. Oper Res Q 23(4):413–431

Rosenzweig C, Solecki WD, Blake R, Bowman M, Faris C, Gornitz V, Horton R, Jacob K, Le Blanc A, Leichenko R, Linkin M, Major D, O'Grady M, Patrick L, Sussman E, Yohe G, Zimmerman R (2011) Developing coastal adaptation to climate change in the New York City infrastructure-shed: process, approach, tools, and strategies. Clim Chang 106(1):93–127

Savage LT (1951) The Theory of Statistical Decisions. J Am Stat Assoc 46(253):55–67

Simon HA (1955) Theories of Decision-Making in Economics and Behavioral Science. Am Econ Rev 49(3):253–283

Swanson DA, Barg S, Tyler S, Venema H, Tomar S, Bhadwal S, Nair S, Roy D, Drexhage J (2010) Seven tools for creating adaptive policies. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 77(6):924–939

Swanson DA, Bhadwal S (eds) (2009) Creating Adaptive Policies: A Guide for Policy-making in an Uncertain World. Sage,

van der Brugge R, Rotmans J, Loorbach D (2005) The transition in Dutch water management. Reg Environ Chang 5:164–176

van Deursen WPA (1995) Geographical information systems and dynamic models. Utrecht University, Utrecht

van Rossum G (1995) Python Reference Manual. CWI,

Wald A (1945) Statistical Decision Functions which Minimize the Maximum Risk. Ann Math 46(2):265–280

Walker WE, Marchau VAWJ, Swanson DA (2010) Addressing deep uncertainty using adaptive policies: Introduction to section 2. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 77(6):917–923

Walker WE, Rahman SA, Cave J (2001) Adaptive Policies, Policy Analysis, and Policymaking. Eur J Oper Res 128(2):282–289

Webster M, Santen N, Parpas P (2011) An approximate dynamic programming framework for modeling global climate poicy under decision-dependent uncertainty. MIT,

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of a Special Issue on ‘Uncertainty and Climate Change Adaptation’ with Guest Editors Tiago Capela Lourenço, Ana Rovisco, Suraje Dessai, Richard Moss and Arthur Petersen.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 1102 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwakkel, J.H., Haasnoot, M. & Walker, W.E. Developing dynamic adaptive policy pathways: a computer-assisted approach for developing adaptive strategies for a deeply uncertain world. Climatic Change 132, 373–386 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1210-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1210-4