Abstract

The Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) is one of the most used instruments to assess anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents. Extensive research has been conducted to examine its psychometric properties and to develop other versions of the scale. The objective of this study was to examine the psychometric properties and factorial structure of the SCAS across different versions and populations. This systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines and was registered. APA PsycINFO, Web of Science (Core Collection) and MEDLINE (PubMed) were searched. Fifty-two studies were included in this systematic review. They examined the factor structure, convergent and divergent validity, and internal consistency of the scale. The most supported model was the original six-factor model, followed by the higher order six-factor model for the long version of the SCAS. Studies provided evidence of convergent validity and internal consistency. It is concluded that the SCAS is a valid and reliable instrument for assessing anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents, with a six-factor model structure well supported in most populations. Further research on the psychometric properties and factor structure of other versions of the scale and its application to clinical populations is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2019, 58 million children and adolescents were living with an anxiety disorder (AD) worldwide [1]. ADs are characterized by the experience of impairing fear and worry and are related to behavioral problems [2]. In childhood, ADs are one of the most prevalent and impairing mental health problems and usually co-occur with other disorders, especially depression [3]. According to the World Health Organization [4], around 3.6% of children between the ages of 10–14 experience an AD. If not recognized and treated properly, ADs can become chronic, severely impact children and adolescents’ quality of life, and lead to subsequent adult negative psychosocial functioning [5]. Therefore, having valid and reliable self-report instruments becomes crucial to early detect anxiety symptoms [6].

The Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) [7, 8] is widely used by clinicians and researchers due to several reasons [6, 9]: (1) the SCAS was originally designed for children and adolescents, what makes it more specific for this population [7, 8]; (2) it comprises symptoms of the most prevalent DSM-5 ADs [2, 7, 8]; (3) the scale has shown good psychometric properties and its factor structure has been previously confirmed in several studies (e.g., [6, 10]); and (4) it is cost-efficient and provides sufficient clinical information to guide diagnosis and treatment efficiently [6, 11]. The SCAS was originally developed as a self-report measure that assessed the severity of anxiety symptoms in Australian children and adolescents from 8 to 14 years old [7]. More recently, there has been extensive research on studying the psychometric properties of the scale on samples from many different countries, and efforts have been made on the development of other versions of the scale, such as the parent reported [12], the teacher reported [13, 14], the preschoolers’ version (PAS) [15], and shortened versions of the scale [16].

Although there are many studies that have proven the SCAS as a valid and reliable assessment instrument and there is extensive literature supporting the six-factor model found in original studies in samples from different cultures [7, 8, 17], it should be noted that certain variability has been found in the psychometric properties of the scale [9, 18] and other models rather than the pioneer six-factor model have shown better fit for their data [18]. The SCAS is considered to be one of the most commonly used scales in both clinical practice and research [9], but systematic research efforts are needed to synthesize available and recent evidence on the factor structure and psychometric properties of the scale for several reasons. First, the data from the previously published systematic review on the psychometric properties of the scale [6] had to be updated as several studies were published afterwards [19, 20]. Second, this meta-analysis included only the self-reported version of the SCAS. In this regard, given the extensive use of the preschool, brief and parent versions of the scale, there was a need to summarize the available literature on the psychometric properties and factor structure of these versions.

Therefore, this study aimed at conducting a systematic review that synthesized the psychometric properties and factorial structure of the SCAS across different versions and populations. The specific objectives were: (1) to summarize and describe the available studies aimed at examining the psychometric properties and/or factor structure of the SCAS; (2) to determine the methods and number of factors that best fit the data from the different populations, and (3) to assess the convergent validity, divergent validity, and reliability of the different versions of the scale.

Method

Registration and Guidelines

The systematic review was performed according to an established protocol registered on PROSPERO (Registration Number: CRD42022365563). This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA 2020) statement [21,22,23].

Search Procedure and Eligibility Criteria

This systematic review examined the studies aimed at describing the psychometric properties of the SCAS in all its versions (i.e., self-report, parent, or teacher versions) in both community and clinical samples. A comprehensive search was performed by two authors (MSO and TGL) in the following bibliographic databases: APA PsycINFO, Web of Science (Core Collection) and MEDLINE (PubMed). The following terms were combined as follows: (“Spence Children Anxiety Scale” OR “SCAS” OR “Preschool Anxiety Scale”) AND (“psychometric properties” OR “factor analys*” OR “factor structure*” OR “validity” OR “validation”). The detailed search strategy can be found in Appendix 1.

The Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Study Design (PICOS) statement [24] was used to establish the following eligibility criteria:

-

Population: children or adolescents under the age of 18 inclusive, and their parents or teachers for the parent and teacher versions, respectively. Community and clinical samples were included.

-

Intervention or exposure: the SCAS [7] in all its versions.

-

Comparison: other instruments that assess anxiety or other symptoms for the calculation of the convergent and divergent validity of the SCAS, respectively.

-

Outcomes: the psychometric properties or the factor structure of the SCAS.

Studies were excluded if they did not report the psychometric properties or the factor structure of the SCAS, if the sample included adolescents over 18 years of age, or if they were not written in English or Spanish.

An Excel file was created to export all the results and duplicates were deleted. Two authors (MSO and TGL) independently screened the remaining records by title and abstract. They then independently screened the records by full-text. Disagreements were consulted to a third author (MOA) and agreement was reached by consensus.

Data Extraction

Two authors (MSO and TGL) extracted the data independently using previously designed data extraction forms in an Excel file. For Table 1, the following data was extracted: first author and year of publication, version of the scale (PAS or SCAS, and if it was the brief version [yes/no]), informant (parent, child, or teacher), type of population (community or clinical), country of study, sample size, percentage of females (%), and age range. For Table 2, regarding the factor structure of the scale, the following information was extracted: mean age (and standard deviation), methods used (exploratory factor analysis [EFA] and/or confirmatory factor analysis [CFA]), number of factors, and percentage of variance explained. For Table 3, about the psychometric properties, it was extracted: Pearson’s r or Spearman’s ρ for convergent and divergent validity, and Cronbach’s alpha for the SCAS total score, subscales (Cronbach’s alpha range), and test–retest.

Results

Identification of Articles

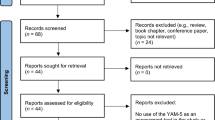

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the literature search process. The initial search across all databases identified 516 records (332 records after removing duplicates). Three additional records were identified through citation searching. After screening by title and abstract, sixty-five records were full-text reviewed for eligibility and sixteen studies were excluded (reasons for exclusion for each record are presented in Appendix 2). Fifty-two studies were included in this systematic review.

PRISMA Flow Diagram. Note. From “The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews”, by M. J. Page et al., 2021, BMJ, 372(71), p. 5 (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71). Distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

Studies and Sample Characteristics

The characteristics of the fifty-two included studies are shown in Table 1. For ease of reading, tables are organized systematically according to the version, informant, and type of population included in the study. The total sample consisted of 52,785 participants: 5,145 parents for the PAS; 4,596 children, 1,647 parents, and 215 teachers for the brief-version of the SCAS; and 34,375 children and 7,844 parents for the traditional version of the SCAS. Participants were from twenty-six different countries, the percentage of females ranged from 0% in the study of Carruthers et al. [25] to 83.90% in the study of Ishikawa et al. [26]; and the ages ranged from 2 to 6 years old for the PAS, and from 5 to 18 years old for the SCAS.

Since the publication of the original scale by Spence [7], eighteen articles have been published before 2012 and thirty-three in the last ten years. Of the twenty-two records, six focused on the preschool version of the SCAS, the PAS [20, 27,28,29,30,31]. Six reported data on the short version: four with the child as informant [16, 32,33,34]; one with the parent [35]; and one with the child, parent, and teacher [14]. The rest of the studies used the long version of the SCAS: twenty-four used the child-reported version, eight the parent-reported version, and eight used both.

Only six studies reported data exclusively on clinical population: children with any AD [19], children with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) [25, 36,37,38], and children who presented both disorders [39].

PAS and SCAS Factor Structure

Data regarding the PAS and SCAS factor structure is shown in Table 2. Of the six studies that examined the factor structure of the preschoolers’ version of the SCAS, only one study used exploratory factor analysis (EFA), four used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and one used both. Four studies supported a five-correlated-factor structure (i.e., social phobia [SOP], separation anxiety [SAD], generalized anxiety [GAD], obsessive–compulsive disorder [OCD] and physical injury fears [PIF]). The study of Maharjan et al. [20] found a better fit for the data after removing three items from the scale, i.e., item 2, 3, and 22. Two studies supported a four-correlated model (i.e., GAD, SOP, SA, and specific fears). The study by Edwards et al. [30] proposed all factors loading on a higher order “anxiety” factor, while GuðmundsdÓttir et al. [27] found a decent fit for a four-factor model in the EFA but not in CFA testing the four-factor model proposed by Edwards et al. [30].

Of the six studies focusing on the brief version of the SCAS (SCAS-S), only five reported data on the factor structure. Two studies validated the five-factor structure of the SCAS-S [16, 33]. The results of the factor analysis performed by Ahlen and colleagues found good support for a structure comprising five group factors loading upon a high general factor [16]. The rest of the studies revealed a good fit for the one-factor structure of the SCAS-S [32, 34, 35].

Thirty-five studies examined the SCAS factor structure both children and parent versions. Three studies used EFA, twenty-five used CFA, six used both EFA and CFA, one used Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and one used both CFA and PCA. Regarding the nine studies that used EFA, two of them were the original by Spence [8, 17], that found support for the six-factor model. Another study found support for this model [40], while the remaining six found support for a six-factor model but different from the original [39, 41], for a seven-factor model [39], for a five-factor model [10, 41, 42], and for a four-factor model [43]. About the studies using CFA, twenty-one found support for the original six-factor model [7, 8, 17], six for the original six-factor higher-order model [7, 8, 17], five for both. Four studies found a better fit for a five-factor model [26, 42, 44, 45].

SCAS Psychometric Properties

Data regarding the psychometric properties of the SCAS is presented in Table 3. Several instruments have been used to test the validity of the scale, among them, it is to note the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [46] or the Child Behavior Checklist (CBLC) [47]. Studies report correlations from 0.41 to 0.57 when comparing the scores of the SCAS with the total scores of the SDQ, and from 0.34 to 0.76 when comparing them with the Emotional Symptoms Subscale of that instrument. With other instruments especially designed to evaluate anxiety symptoms, higher correlations are found, ranging from 0.76 to 0.85. Concerning the divergent validity of the scale, it should be highlighted that only thirty of the fifty-two studies reported data on this regard. The most used scale was SDQ, especially the Hyperactivity, Inattention, and Conduct Problems Subscales. Correlations with these subscales ranged from 0.00 to 0.39; although the study of Carrillo and colleagues [48] found a correlation with the Conduct Problems Subscale of 0.69. The CDI, also used to test the divergent validity of the SCAS in seven studies, showed correlations from -0.004 to 0.72, which is indicative that constructs measured by both instruments are related.

Forty-four studies explored the reliability of the total scale, and forty-two reported data on the reliability of each subscale. Cronbach’s alphas for the total score ranged from 0.65 to 0.97, and from 0.42 to 0.90 for the subscales. Thirty-two studies of the forty-two that reported data concerning the reliability of the subscales found that the PIF subscale had the lowest value (0.43 to 0.68). Thirty-five studies of the forty-two found that the Panic Attack and Agoraphobia (PA) subscale had the highest values (0.70 to 0.87). Only twenty-seven studies explored the test–retest reliability, and Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.60 to 0.91.

Discussion

The present systematic review aimed to summarize the available literature on the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale in all its versions. It is the first to bring together all studies on the factor structure and the psychometric properties of the SCAS, including preschool, brief, parent, child, and teacher versions of the instrument. The specific objectives were: (1) to describe the studies aimed at examining the psychometric properties and/or factor structure of the SCAS; (2) to determine the factor structure that was best supported in the literature; and (3) to assess the validity and reliability.

First, it is important to note that valid and reliable measures for assessing anxiety symptoms in infant populations have attracted considerable attention in the literature over the past few years, as can be inferred from the increasing number of publications on the subject over the past decade and the large number of people participating in the studies (more than 50,000 people were involved in the studies included in this systematic review). Most of the studies focused on the long traditional version of the SCAS, although recent efforts are pivoting towards evaluating the properties of other versions of the scale, such as the preschool and brief versions of the SCAS, or in clinical populations (e.g., autism disorders), necessary to meet the growing demand for the assessment of anxiety symptomatology in other developmental stages, in different contexts (e.g., schools—through teacher versions of the scale), and in children suffering from other health problems.

Second, the results of the studies indicated that there is a variability in the factor structure that is best supported for the PAS and for the short version of the SCAS, warranting further research in this regard. Regarding the SCAS, the most supported model was the original six-factor model, followed by the higher six-factor model [7, 8, 17], confirming data from the previous systematic review about the factor structure of the children version of the scale [6]. Participants in this study came from twenty-six different countries, suggesting that this scale is applicable across countries. However, studies with participants from countries such as China [45], Japan [26, 42], Malaysia [44], Germany [10, 41], or England [39], found support for other factor structures. Differences in the structure are unlikely to be due solely to social factors, as samples from countries with similar cultural values were indeed able to replicate the original models [6]. Authors have proposed factors such as personality traits, experimental designs, or statistics to explain these differences [6, 41, 49]. In this sense, the study by Glod et al. [39], for example, found differences in the factor structures of the scale for children with anxiety disorders and autism disorders. Comorbidities with other health problems are therefore suggested as another factor that should be further investigated as a potential variable influencing the factor structure differences across population groups.

Third, studies reported high correlations between the SCAS and other scales, such as the SDQ or the SCARED, providing evidence of convergent validity. Lower correlations were found between anxiety and other constructs derived from the SDQ (i.e., conduct problems, hyperactivity, or inattention). Only two studies [32, 50] reported null correlations between the SCAS and the prosocial subscale of the SDQ, making it difficult to draw definite conclusions about divergent validity. Reliability for the total scale ranged from good to excellent for the PAS, from acceptable to good for the brief version, and from acceptable to excellent for the long version of the scale. Only one study [37] reported a questionable reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.65), maybe since the sample was quite diverse, including children with ASD and intellectual disability. Further research to evaluate the reliability of the scale in clinical populations is warranted. The reliability of the PIF subscale ranged from unacceptable to questionable, previously explained by the low number of items and the variability of the situations they describe [51, 52]. The PA subscale showed the highest reliability in more than eighty percent of the studies, ranging from good to acceptable. Most studies reported good to acceptable test–retest reliability, showing evidence of the scale’s good temporal stability for measuring anxiety symptoms.

Finally, it is of utmost research and clinical significance to conduct a comparative of the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS) in relation to other pertinent and widely employed measures utilized for assessing anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents, namely the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) [53], the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) [54], and the Youth Anxiety Measure for DSM-5 (YAM-5) [55]. The development of the SCAS, SCARED, and MASC emerged in response to the clinical and research demands following the release of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) in 1994 [56]. Conversely, the YAM-5 represents a more recent scale aligned with the DSM-5, which introduced modifications to the classification of anxiety disorders by excluding certain disorders (e.g., obsessive–compulsive disorder) and incorporating others (e.g., selective mutism) [57, 58]. Regarding the MASC-2, limitations have been previously documented by other scholars [59]. These include its cost, which is computed per purchased form, its limited availability in languages beyond English, and its relatively smaller research foundation when compared to the SCAS and SCARED [59]. In contrast, both the SCAS and SCARED have undergone extensive translation, validation, and research-based examination, thus promoting their widespread adoption and facilitating cross-cultural utilization of empirically grounded instruments by clinicians and researchers across countries. Although a prior meta-analysis published in 2018 suggested that the SCAS possesses a more limited research base than the SCARED [59], the past five years have witnessed the publication of over ten studies exploring the psychometric and factor structure of the SCAS, thereby providing evidence for the validity of its factor structure and psychometric properties. This surge in interest within the scientific community towards the utilization of various SCAS versions, including the abbreviated and preschool adaptations. A notable advantage of the SCAS, in comparison to the SCARED, may lie in its shorter length, as the longest version of the SCAS comprises 44 items, whereas the SCARED encompasses a range of 38 to 71 items, depending on the variant [59]. Additionally, recent efforts have been dedicated to developing the SCAS for the assessment of anxiety symptoms in children under the age of 8, as research indicates that certain anxiety disorders exhibit an onset peak before this age (e.g., specific phobias or separation anxiety disorder) [60]. Regarding the YAM-5, multiple studies have demonstrated its reliability and validity in assessing DSM-5 anxiety disorder symptoms [55, 61]. Nevertheless, as a newly developed measure, further exploration with diverse international samples is warranted, given its capacity to shed light on new diagnostic categories within the evolving classification systems that may not be captured by older instruments.

Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

This study is limited by several facts. First, although the search was exhaustive and multiple databases were searched, some studies may have been excluded, which may have influenced the conclusions drawn from the synthesized results. Second, factorial invariance and risk of bias were not examined in this paper and should be prioritized in future studies. Third, drawing conclusions about the psychometric properties and factor structure of the preschoolers’ and the short version of the scale and in clinical populations was limited by the sparse literature that has been published to date. We suggest this should be examined in further studies.

Despite these limitations, there are several notable strengths of this work. This study is based on the PRISMA guidelines, and all decisions made in the course of its development were reported, which contributes to transparency and makes it replicable to update the data in the future. In the present work, we extended our previous systematic review of the SCAS [6] by incorporating other versions of the scale along with some psychometric properties not previously explored by this meta-analysis (i.e., test–retest reliability). This research is hoping to contribute to the direction of helping clarify the fact that this scale, together with the obvious advantages in terms of its usefulness, has enough psychometric quality to be used in both clinical and research settings.

Summary

This systematic review provides an overview of the studies that have examined the psychometric quality of one of the most widely used scales for assessing anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents, the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale. This work followed PRISMA guidelines and included fifty-two studies exploring the psychometric properties or the factor structure of the scale. Most studies focused on the long version of the scale. Overall, it can be concluded that this version is a valid and reliable instrument for assessing anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents, with a six-factor model structure that is well supported in most populations. Further research on the psychometric properties and factor structure of other versions of the scale and its application to clinical populations is warranted. This systematic review expands the available knowledge on the SCAS, and in particular on the previously reported systematic review of the instrument, by including other versions of the scale and populations in their samples.

Data Availability

There are no other datasets associated with this systematic review beyond those presented in the manuscript and its appendix.

References

References marked by an asterisk indicate studies included in the systematic review

Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (2019) Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/. Accessed 28 Nov 2022

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Orgilés M, Garrigós E, Espada JP, Morales A (2020) How does a CBT-based transdiagnostic program for separation anxiety symptoms work in children effects of super skills for life. J Clin Psychol Child Adolesc. https://doi.org/10.21134/rpcna.2020.07.2.1

World Health Organization (2021) Adolescent mental health. In: Newsroom—Fact sheets. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health.

Essau CA, Lewinsohn PM, Olaya B, Seeley JR (2014) Anxiety disorders in adolescents and psychosocial outcomes at age 30. J Affect Disord 163:125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.033

Orgilés M, Fernández-Martínez I, Guillén-Riquelme A et al (2016) A systematic review of the factor structure and reliability of the Spence children’s anxiety scale. J Affect Disord 190:333–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.055

*Spence SH (1997) Structure of anxiety symptoms among children: a confirmatory factor-analytic study. J Abnorm Psychol 106:280–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.106.2.280

*Spence SH (1998) A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behav Res Ther 36:545–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00034-5

Orgilés M, Spence SH, Marzo JC et al (2014) Psychometric properties and factorial structure of the Spence children’s anxiety scale (SCAS) in Spanish adolescents. J Pers Assess 96:95–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.816716

*Essau CA, Muris P, Ederer EM (2002) Reliability and validity of the Spence children’s anxiety scale and the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders in German children. Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 33:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(02)00005-8

Brown TA, Barlow DH (2009) A proposal for a dimensional classification system based on the shared features of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: implications for assessment and treatment. Psychol Assess 21:256–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016608

*Nauta MH, Scholing A, Rapee RM et al (2004) A parent-report measure of children’s anxiety: psychometric properties and comparison with child-report in a clinic and normal sample. Behav Res Ther 42:813–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00200-6

Lyneham HJ, Street AK, Abbott MJ, Rapee RM (2008) Psychometric properties of the school anxiety scale—teacher report (SAS-TR). J Anxiety Disord 22:292–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.001

*Reardon T, Spence SH, Hesse J et al (2018) Identifying children with anxiety disorders using brief versions of the Spence children’s anxiety scale for children, parents, and teachers. Psychol Assess 30:1342–1355. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000570

Spence SH, Rapee R, McDonald C, Ingram M (2001) The structure of anxiety symptoms among preschoolers. Behav Res Ther 39:1293–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00098-X

*Ahlen J, Vigerland S, Ghaderi A (2018) Development of the Spence children’s anxiety scale—short version (SCAS-S). J Psychopathol Behav Assess 40:288–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-017-9637-3

*Spence SH, Barrett PM, Turner CM (2003) Psychometric properties of the Spence children’s anxiety scale with young adolescents. J Anxiety Disord 17:605–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00236-0

*Essau CA, Sasagawa S, Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous X et al (2011) Psychometric properties of the Spence child anxiety scale with adolescents from five European countries. J Anxiety Disord 25:19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.07.001

*Forcadell E, García-Delgar B, Medrano L et al (2021) Spanish validation of the parent version of the Spence children’s anxiety scale (SCAS-P) in a clinical sample. Behav Psychol 29:365–381. https://doi.org/10.51668/bp.8321209n

*Maharjan S, Rana M, Neupane B et al (2022) Psychometric properties of Nepalese preschool anxiety scale among preschool children: a cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.808

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM et al (2021) PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RSA (1995) The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. https://doi.org/10.7326/ACPJC-1995-123-3-A12

*Carruthers S, Kent R, Hollocks MJ, Simonoff E (2020) Testing the psychometric properties of the Spence children’s anxiety scale (SCAS) and the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED) in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 50:2625–2632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3774-8

*Ishikawa S, Shimotsu S, Ono T et al (2014) A parental report of children’s anxiety symptoms in Japan. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 45:306–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-013-0401-y

*GuðmundsdÓttir HR, Karlsson Þ, Þó ÆvarsdÓttir (2019) The psychometric properties of the Icelandic version of the preschool anxiety scale-revised (PAS-R). Nord Psychol 71:218–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2019.1586571

*Leung GSM, Yau KC, Yuen SY (2019) Validation of the preschool anxiety scale-traditional Chinese (PAS-TC) in Hong Kong. Appl Res Qual Life 14:359–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9596-1

*Wang M, Zhao J (2015) Anxiety disorder symptoms in Chinese preschool children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 46:158–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0461-7

*Edwards SL, Rapee RM, Kennedy SJ, Spence SH (2010) The assessment of anxiety symptoms in preschool-aged children: the revised preschool anxiety scale. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 39:400–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374411003691701

*Broeren S, Muris P (2008) Psychometric evaluation of two new parent-rating scales for measuring anxiety symptoms in young Dutch children. J Anxiety Disord 22:949–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.09.008

Rodríguez-Menchón M, Orgilés M, Espada JP, Morales A (2022) Validation of the brief version of the Spence children’s anxiety scale for Spanish children (SCAS-C-8). J Clin Psychol 78:1093–1102. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23263

*Gong J, Wang M-C, Zhang X, Yang W (2021) Measurement invariance and psychometric properties of the Spence children’s anxiety scale-short version (SCAS-S) in Chinese students. Curr Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02237-x

*Deeba F, Rapee RM, Prvan T (2015) Psychometric properties of two measures of childhood internalizing problems in a Bangladeshi sample. British J Clin Psychol 54:214–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12071

*Orgilés M, Morales A, Espada JP, Rodríguez-Menchón M (2022) Early detection of anxiety problems in childhood: Spanish validation of the brief Spence children’s anxiety scale for parents. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 27:836–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045221089907

*Zainal H, Magiati I, Tan JW-L et al (2014) A preliminary investigation of the Spence children’s anxiety parent scale as a screening tool for anxiety in young people with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 44:1982–1994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2075-0

*Jitlina K, Zumbo B, Mirenda P et al (2017) Psychometric properties of the Spence children’s anxiety scale: parent report in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 47:3847–3856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3110-8

*Magiati I, Lerh JW, Hollocks MJ et al (2017) The measurement properties of the Spence children’s anxiety scale-parent version in a large international pooled sample of young people with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res 10:1629–1652. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1809

*Glod M, Creswell C, Waite P et al (2017) Comparisons of the factor structure and measurement invariance of the Spence children’s anxiety scale—parent version in children with autism spectrum disorder and typically developing anxious children. J Autism Dev Disord 47:3834–3846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3118-0

*Mellon RC, Moutavelis AG (2007) Structure, developmental course, and correlates of children’s anxiety disorder-related behavior in a Hellenic community sample. J Anxiety Disord 21:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.008

*Essau CA, Leung PWL, Conradt J et al (2008) Anxiety symptoms in Chinese and German adolescents: their relationship with early learning experiences, perfectionism, and learning motivation. Depress Anxiety 25:801–810. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20334

*Ishikawa S, Sato H, Sasagawa S (2009) Anxiety disorder symptoms in Japanese children and adolescents. J Anxiety Disord 23:104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.04.003

*Muris P, Schmidt H, Engelbrecht P, Perold M (2002) DSM-IV–defined anxiety disorder symptoms in South African children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41:1360–1368. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200211000-00018

*Ahmadi A, Mustaffa MS, Haghdoost A et al (2015) Cross-cultural adaptation of the Spence children’s anxiety scale in Malaysia. Trends Psychiatry Psychother 37:37–41. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2014-0038

*Li JC, Lau W, Au TK (2011) Psychometric properties of the Spence children’s anxiety scale in a Hong Kong Chinese community sample. J Anxiety Disord 25:584–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.01.007

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: aresearch note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1469-7610.1997.TB01545.X

Achenbach TM (1999) The child behavior Checklist and related instruments. In: Erlbaum Lawrence (ed) The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment, 2nd edition. Associates Publishers, Mahwah, pp 429–466

*Carrillo F, Godoy A, Gavino A et al (2012) Escala de ansiedad infantil de Spence (Spence children´s anxiety scale, SCAS): fiabilidad y validez de la versión española. Behav Psychol 20:529–545

*Essau CA, Olaya B, Pasha G et al (2012) The structure of anxiety symptoms among adolescents in Iran: a confirmatory factor analytic study of the Spence children’s anxiety scale. J Anxiety Disor 26:871–878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.08.001

*Qadir F, Maqsood A, us-Sahar N et al (2018) Factor structure of the Urdu version of the Spence children’s anxiety scale in Pakistan. Behav Med 44:100–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2016.1276427

*Whiteside SP, Brown AM (2008) Exploring the utility of the Spence children’s anxiety scales parent- and child-report forms in a North American sample. J Anxiety Disord 22:1440–1446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.02.006

Ollendick TH, Raishevich N, Davis TE III et al (2010) Specific phobia in youth: phenomenology and psychological characteristics. Behav Ther 41:133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2009.02.002

Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D et al (1997) The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(4):545–553. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199704000-00018

March JS, Parker JDA, Sullivan PS et al (1997) The multidimensional anxiety scale for children (MASC): factor structure, reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(4):554–565. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019

Muris P, Simon E, Lijphart E et al (2017) The youth anxiety measure for DSM-5 (YAM-5): development and first psychometric evidence of a new scale for assessing anxiety disorders symptoms of children and adolescents. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 48(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0648-1

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.).

Muris P, Mannens J, Peters L et al (2017) The youth anxiety measure for DSM-5 (YAM-5): correlations with anxiety, fear, and depression scales in non-clinical children. J Anxiety Disord 51:72–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.06.001

Muris P, Ollendick TH (2015) Children who are anxious in silence: a review on selective mutism, the new anxiety disorder in DSM-5. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 18:151–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-015-0181-y

Runyon K, Chesnut ST, Burley H (2018) Screening for childhood anxiety: a meta-analysis of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders. J Affect Disord 240:220–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.049

Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M et al (2022) Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale metaanalysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry 27:281–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

Simon E, Bos AER, Verboon P et al (2017) Psychometric properties of the youth anxiety measure for DSM-5 (YAM-5) in a community sample. Pers Individ Dif 116:258–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.058

Studies Included in the Systematic Review not Explicitly Cited in the Article

Arendt K, Hougaard E, Thastum M (2014) Psychometric properties of the child and parent versions of Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale in a Danish community and clinical sample. J Anxiety Disor 28:947–956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.09.021

DeSousa DA, Pereira AS, Petersen CS et al (2014) Psychometric properties of the Brazilian-Portuguese version of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS): Self- and parent-report versions. J Anxiety Disor 28:427–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.03.006

Di Riso D, Chessa D, Bobbio A et al (2013) Factorial structure of the SCAS and its relationship with the SDQ. Eur J Psychol Assess 29(1):28–35. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000117

Godoy A, Gavino Lázaro A, Carrillo F, et al (2011) Composición factorial de la versión española de la Spence Children Anxiety Scale (SCAS). Psicothema 23.

Hernández-Guzmán L, Bermúdez-Ornelas G, Spence SH et al (2010) Spanish version of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS). R Latinoam Psicol 42:13–24

Ishikawa S, Takeno Y, Sato Y et al (2018) Psychometric properties of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale with adolescents in Japanese high schools. School Ment Health 10(3):275–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9242-3

Li JB, Delvecchio E, Di Riso D et al (2016) The parent-version of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS-P) in Chinese and Italian community samples: Validation and cross-cultural comparison. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 47(3):369–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0572-9

Muris P, Merckelbach H, Ollendick T et al (2002) Three traditional and three new childhood anxiety questionnaires: their reliability and validity in a normal adolescent sample. Behav Res Ther 40(7):753–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00056-0

Olofsdotter S, Sonnby K, Vadlin S et al (2016) Assessing adolescent anxiety in general psychiatric care. Assessment 23(6):744–757. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115583858

Orgilés M, Méndez X, Spence SH et al (2012) Spanish validation of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 43(2):271–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-011-0265-y

Orgilés M, Rodríguez-Menchón M, Fernández-Martínez I et al (2019) Validation of the parent report version of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS-P) for Spanish children. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 24(4):776–790. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104519835579

Orgilés M, Spence SH, Marzo JC et al (2013) Psychometric properties and factorial structure of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) in Spanish adolescents. J Pers Assess 96(1):95–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.816716

Rodríguez-Menchón M, Orgilés M, Espada JP et al (2022) Validation of the brief version of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale for Spanish children (SCAS-C-8). J Clin Psychol 78(6):1093–1102. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23263

Tortella-Feliu M, Balle M, Servera M, et al (2005) Propiedades psicométricas de la adaptación catalana de la “Escala de ansiedad en niños/as de Spence (SCAS).” Behav Psychol 13(1).

Tsocheva I, Sasagawa S, Georgiou G, et al (2013) Psychometric properties of the Bulgarian translation of the Spence Childrens Anxiety Scale. J Psychol Abnorm Child 01(01). https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-9525.1000101

Wang M, Meng Q, Liu L et al (2016) Reliability and validity of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale for parents in mainland Chinese children and adolescents. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 47(5):830–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0615-2

Zhao J, Xing X, Wang M (2012) Psychometric properties of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS) in mainland Chinese children and adolescents. J Anxiety Disor 26(7):728–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.05.006

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the contribution of children, adolescents, families, and teachers that took part in the studies included in this systematic review.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Teresa Galán-Luque was supported by the Ministry of Universities of Spain (FPU20/00893). Marina Serrano-Ortiz was funded by Miguel Hernández University (04-541-4-2022-0032).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TGL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization. MSO: Formal analysis, Data Curation. MO: Conceptualization, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors review the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The systematic review was performed according to an established protocol registered on PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42022365563).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Galán-Luque, T., Serrano-Ortiz, M. & Orgilés, M. Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale: A 25-Year Systematic Review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01566-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01566-1