Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate patient, oncologist and nurse perspectives on side effects and patient reported outcomes (PROs) with the question of how to optimize side effect management and PRO tools in this unique population.

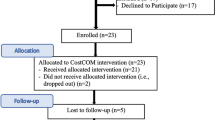

Methods

This pilot study utilized a mixed method explanatory design. Patients receiving intravenous (IV) chemotherapy from June to August 2020 were surveyed about side effect burden and PRO system preferences. Providers and nurses (PN) completed complementary surveys. Semi-structured phone interviews were conducted among a subset of each group.

Results

Of 90 patient surveys collected; 51.1% minority, 35.6% rural, and 40.0% income < $30,000, 48% felt side effect management was a significant issue. All patients reported access to a communication device but 12.2% did not own a cell phone; 68% smart phone, 20% cell phone, 22% landline, 53% computer, and 39% tablet. Patients preferred a response to reported side effects within 0–3 h (73%) while only 29% of the 55 PN surveyed did (p < 0.0001). Interviews reinforced that side effect burden was a significant issue, the varied communication devices, and a PRO system could improve side effect management.

Conclusion

In a non-White, rural and low-income patient population, 87.8% of patients reported owning a cell phone. Although all agreed side effect management was a prominent issue, expectations between patients and PN differed substantially. Qualitative data echoed the above and providing concrete suggestions to inform development of a PRO program and side effect mitigation strategies among a diverse patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to fact that they could be linked to individual patients but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shapiro CL, Recht A (2001) Side effects of adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 344(26):1997–2008. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200106283442607

Lin JJ, Chao J, Bickell NA, Wisnivesky JP (2017) Patient-provider communication and hormonal therapy side effects in breast cancer survivors. Women Health 57(8):976–989. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2016.1235071

Gandhi S et al (2015) Oral anticancer medication adherence, toxicity reporting, and counseling: a study comparing health care providers and patients. J Oncol Pract 11(6):498–504. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2015.004572

Nabulsi NA et al (2020) Self-reported health and survival in older patients diagnosed with multiple myeloma. Cancer Causes Control 31(7):641–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-020-01305-0

Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, Wever LDV, Aaronson NK (2002) Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288(23):3027–3034. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.23.3027

Kotronoulas G et al (2014) What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 32(14):1480–1501. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5948

Basch E (2010) The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med 362(10):865–869. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp0911494

Snyder CF et al (2012) Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res 21(8):1305–1314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-0054-x

Reeve BB et al (2013) ISOQOL recommends minimum standards for patient-reported outcome measures used in patient-centered outcomes and comparative effectiveness research. Qual Life Res 22(8):1889–1905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0344-y

Basch E et al (2015) Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830

Jackman DM et al (2017) Cost and Survival analysis before and after implementation of Dana-Farber clinical pathways for patients with stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. JOP 13(4):e346–e352. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2017.021741

Daly B et al (2018) Oncology clinical pathways: charting the landscape of pathway providers. J Oncol Practice 14(3):e194–e200. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.17.00033

de Souza JA et al (2017) Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: the validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer 123(3):476–484. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30369

Navigating Cancer’s Triage Software with Symptom Management Pathways Facilitates $3.4 Million in Annual Savings. PRWeb. https://www.prweb.com/releases/2017/08/prweb14609775.htm. Accessed 5 Nov 2018

Bultijnck R et al (2018) Clinical pathway improves implementation of evidence-based strategies for the management of androgen deprivation therapy-induced side effects in men with prostate cancer. BJU Int 121(4):610–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14086

Todo M et al (2018) Improvement of treatment outcomes after implementation of comprehensive pharmaceutical care in breast cancer patients receiving everolimus and exemestane. Pharmazie 73(2):110–114. https://doi.org/10.1691/ph.2018.7837

Basch E et al (2017) Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 318(2):197–198. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7156

Mazor KM et al (2012) Toward patient-centered cancer care: patient perceptions of problematic events, impact, and response. J Clin Oncol 30(15):1784–1790. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.38.1384

Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP (2004) Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA 291(22):2720–2726. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.22.2720

ASCO announces new task force to address rural cancer care gap | ASCO. https://www.asco.org/about-asco/press-center/news-releases/asco-announces-new-task-force-address-rural-cancer-care-gap. Accessed 22 Apr 2019

Bzostek S, Goldman N, Pebley A (2007) Why do Hispanics in the USA report poor health? Soc Sci Med 65(5):990–1003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.028

How Rural is New Mexico? – Bureau of Business & Economic Research Blog. https://bber.unm.edu/blog/?p=364. Accessed 22 Apr 2019

Meilleur A, Subramanian SV, Plascak JJ, Fisher JL, Paskett ED, Lamont EB (2013) Rural residence and cancer outcomes in the united states: issues and challenges. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22(10):1657–1667. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0404

New Mexico Report - 2020, Talk poverty. https://talkpoverty.org/state-year-report/new-mexico-2020-report/. Accessed 20 Sept 2021

Marcus AF, Illescas AH, Hohl BC, Llanos AAM (2017) Relationships between social isolation, neighborhood poverty, and cancer mortality in a population-based study of US adults. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173370

Rural New Mexico had the highest poverty rate in the nation according to Census American Community Survey - Albuquerque Business First. https://www.bizjournals.com/albuquerque/news/2016/12/09/rural-nm-has-the-highest-poverty-rate-among-all.html. Accessed 29 Jan 2019

Karen H, Mulloy B, Stephanie Moraga-McHaley DO, MS University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, New Mexico Tribal Occupational Health Needs Assessment: A Report to Native American Communities, p 18

Maze D et al (2021) A mixed methods study exploring the role of perceived side effects on treatment decision-making in older adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). JCO 39:7016–7016. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.7016

Bluethmann SM, Murphy CC, Tiro JA, Mollica MA, Vernon SW, Bartholomew LK (2017) Deconstructing decisions to initiate, maintain, or discontinue adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer survivors: a mixed-methods study. Oncol Nurs Forum 44(3):E101–E110. https://doi.org/10.1188/17.ONF.E101-E110

Tolstrup LK, Pappot H, Bastholt L, Zwisler A-D, Dieperink KB (2020) Patient-reported outcomes during immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma: mixed methods study of patients’ and clinicians’ experiences. J Med Internet Res. https://doi.org/10.2196/14896

Jaffe SA, Guest DD, Sussman AL, Wiggins CL, Anderson J, McDougall JA (2021) A sequential explanatory study of the employment experiences of population-based breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-021-01467-5

Wallen GR et al (2012) Palliative care outcomes in surgical oncology patients with advanced malignancies: a mixed methods approach. Qual Life Res 21(3):405–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-0065-7

LeBlanc TW et al (2015) Perceptions of palliative care among hematologic malignancy specialists: a mixed-methods study. JOP 11(2):e230–e238. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2014.001859

Harley C et al (2012) A mixed methods approach to adapting health-related quality of life measures for use in routine oncology clinical practice. Qual Life Res 21(3):389–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9983-7

Weems MF, Graetz I, Lan R, DeBaer LR, Beeman G (2016) Electronic communication preferences among mothers in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol 36(11):997–1000. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.125

Schrag D, Hanger M (2007) Medical oncologists’ views on communicating with patients about chemotherapy costs: a pilot survey. J Clin Oncol 25(2):233–237. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2437

Patel MR, Shah KS, Shallcross ML (2015) A qualitative study of physician perspectives of cost-related communication and patients’ financial burden with managing chronic disease. BMC Health Serv Res 15:518. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1189-1

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42(2):377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

U. C. Bureau, “2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria,” The United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural/2010-urban-rural.html. Accessed 31 Aug 2021

O’Donnell PH, Dolan ME (2009) Cancer pharmacoethnicity: ethnic differences in susceptibility to the effects of chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 15(15):4806–4814. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0344

Shavers VL, Brown ML (2002) Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. JNCI 94(5):334–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/94.5.334

Yanez B, McGinty HL, Buitrago D, Ramirez AG, Penedo FJ (2016) Cancer outcomes in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: an integrative review and conceptual model of determinants of health. J Lat Psychol 4(2):114–129. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000055

Rivera SC, Kyte DG, Aiyegbusi OL, Slade AL, McMullan C, Calvert MJ (2019) The impact of patient-reported outcome (PRO) data from clinical trials: a systematic review and critical analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 17(1):156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1220-z

Greenhalgh J et al (2018) How do patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) support clinician-patient communication and patient care? A realist synthesis. J Patient-Rep Outcomes 2(1):42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-018-0061-6

Basch E, Barbera L, Kerrigan CL, Velikova G (2018) Implementation of patient-reported outcomes in routine medical care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 38:122–134. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_200383

Representation of minorities and Women in Oncology Clinical Trials: Review of the Past 14 Years | JCO Oncology Practice. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2017.025288. Accessed 28 Mar 2022

Clark LT et al (2019) Increasing diversity in clinical trials: overcoming critical barriers. Curr Probl Cardiol 44(5):148–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2018.11.002

HealthITAnalytics, “strategies for collecting high-quality patient-reported outcomes,” HealthITAnalytics, 2019. https://healthitanalytics.com/news/strategies-for-collecting-high-quality-patient-reported-outcomes. Accessed 29 Mar 2022

Coons SJ et al (2009) Recommendations on evidence needed to support measurement equivalence between electronic and paper-based patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures: ISPOR ePRO Good Research Practices Task Force report. Value Health 12(4):419–429. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00470.x

NQF: patient-reported outcomes: best practices on selection and data collection - final technical report. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2020/09/Patient-Reported_Outcomes__Best_Practices_on_Selection_and_Data_Collection_-_Final_Technical_Report.aspx. Accessed 29 Mar 2022

Haverfield MC, Singer AE, Gray C, Shelley A, Nash A, Lorenz KA (2020) Implementing routine communication about costs of cancer treatment: perspectives of providers, patients, and caregivers. Support Care Cancer 28(9):4255–4262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05274-2

Impact of patient-reported outcomes on clinical practice, p 9 (2016)

Chen J, Ou L, Hollis SJ (2013) A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcome measures on patients, providers and health organisations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Serv Res 13:211. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-211

Nic Giolla Easpaig B et al (2020) What are the attitudes of health professionals regarding patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in oncology practice? A mixed-method synthesis of the qualitative evidence. BMC Health Serv Res 20:102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4939-7

Girgis A et al (2017) eHealth system for collecting and utilizing patient reported outcome measures for personalized treatment and care (PROMPT-Care) among cancer patients: mixed methods approach to evaluate feasibility and acceptability. J Med Internet Res. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8360

Rutherford C et al (2021) Implementing patient-reported outcome measures into clinical practice across NSW: mixed methods evaluation of the first year. Appl Res Qual Life 16(3):1265–1284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09817-2

Skovlund SE, Troelsen LH, Noergaard LM, Pietraszek A, Jakobsen PE, Ejskjaer N (2021) Feasibility and acceptability of a digital patient-reported outcome tool in routine outpatient diabetes care: mixed methods formative pilot study. JMIR Form Res. https://doi.org/10.2196/28329

Gray CS et al (2021) Assessing the implementation and effectiveness of the electronic patient-reported outcome tool for older adults with complex care needs: mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. https://doi.org/10.2196/29071

Acknowledgments

We thank our infusion floor nurses and Lori Lelii for administering these surveys. We would like to also thank Karen Quezada and Dr. Zoneddy Dayao for the assistance and support during this project, without which this would not have been possible.

Funding

This research was partially supported by University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant NCI P30CA118100 and the Behavioral Measurement and Population Sciences shared resource.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by BT, EB, SAJ, and MK. The first draft of the manuscript was written by BT and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center’s Human Research Protections Office [UNM HRPO] (#19-562).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tawfik, B., Burgess, E., Kosich, M. et al. Patient, provider, and nurse preferences of patient reported outcomes (PRO) and side effect management during cancer treatment of underrepresented racial and ethnic minority groups, rural and economically disadvantaged patients: a mixed methods study. Cancer Causes Control 33, 1193–1205 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-022-01605-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-022-01605-7