Abstract

Purpose

Cancer treatment often leads to work disruptions including loss of income, resulting in long-term financial instability for cancer survivors and their informal caregivers.

Methods

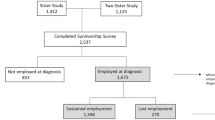

In this sequential explanatory study, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of employment experiences among ethnically diverse, working-age individuals diagnosed with breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer. Following the survey, we conducted semi-structured interviews with cancer survivors and informal caregivers to explore changes in employment status and coping techniques to manage these changes.

Results

Among employed survivors (n = 333), cancer caused numerous work disruptions including issues with physical tasks (53.8%), mental tasks (46.5%) and productivity (76.0%) in the workplace. Prostate cancer survivors reported fewer work disruptions than female breast and male and female colorectal cancer survivors. Paid time off and flexible work schedules were work accommodations reported by 52.6% and 36.3% of survivors, respectively. In an adjusted regression analysis, household income was positively associated with having received a work accommodation. From the qualitative component of the study (survivors n = 17; caregivers n = 11), three key themes emerged: work disruptions, work accommodations, and coping mechanisms to address the disruptions. Survivors and caregivers shared concerns about lack of support at work and resources to navigate issues caused by changes in employment.

Conclusions

This study characterized employment changes among a diverse group of cancer survivors. Work accommodations were identified as a specific unmet need, particularly among low-income cancer survivors. Addressing changes in employment among specific groups of cancer survivors and caregivers is critical to mitigate potential long-term consequences of cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

National Cancer Institute (2015) Age and cancer risk. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/age. Accessed 20 Sep 2019.

Yabroff KR, Warren JL, Knopf K et al (2005) Estimating patient time costs associated with colorectal cancer care. Med Care 43:640–648. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000167177.45020.4a

Spelten ER, Verbeek JHAM, Uitterhoeve ALJ et al (2003) Cancer, fatigue and the return of patients to work - A prospective cohort study. Eur J Cancer 39:1562–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00364-2

Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP et al (2016) Financial hardship associated with cancer in the united states: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 34:259–267. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468

McDougall JA, Banegas MP, Wiggins CL et al (2018) Rural disparities in treatment-related financial hardship and adherence to surveillance colonoscopy in diverse colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 27:1275–1282. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1083

Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, Ramsey SD (2012) Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol 30:1608–1614. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9511

Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A et al (2013) Washington state cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Affair 32:1143–1152. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263

Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L et al (2016) Caring for caregivers and patients: research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer 122:1987–1995

Coumoundouros C, Ould Brahim L, Lambert SD, McCusker J (2019) The direct and indirect financial costs of informal cancer care: a scoping review. Heal Soc Care Community 27:e622–e636. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12808

Veenstra CM, Wallner LP, Jagsi R et al (2017) Long-term economic and employment outcomes among partners of women with early-stage breast cancer. J Oncol Pract 13:e916–e926. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.2017.023606

de Moor JS, Alfano CM, Kent EE et al (2018) Recommendations for research and practice to improve work outcomes among cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst 110:1041–1047. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy154

Mehnert A (2011) Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 77:109–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.01.004

Bradley CJ, Brown KL, Haan M et al (2018) Cancer survivorship and employment: intersection of oral agents, changing workforce dynamics, and employers’ perspectives. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 110:1292–1299. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy172

Neumark D, Bradley CJ, Henry M, Dahman B (2015) Work continuation while treated for breast cancer: the role of workplace accommodations. Ind Labor Relat Rev 68:916–954. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793915586974

Tung I, Lathrop Y, Sonn P (2015) The growing movement for $15. National employment law project

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL (2011) “Choosing a mixed method research design” in designing and conducting mixed methods research, 2nd edn. SAGE Publications, lnc, California

McDougall JA, Anderson J, Adler Jaffe S et al (2020) Food insecurity and forgone medical care among cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol Oncol Pract 16(9):e922–e932

Yabroff KR, Dowling E, Rodriguez J et al (2012) The Medical expenditure panel survey (MEPS) experiences with cancer survivorship supplement. J Cancer Surviv 6:407–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-012-0221-2

Hart LG, Larson EH, Lishner DM (2005) Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am J Public Health 95:1149–1155. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.042432

StataCorp (2017) Stata statistical software: release 15. StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX

Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T et al (2018) Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 52:1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

Maguire M, Delahunt B (2017) Doing a thematic analysis: a practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISHE-J All Irel J Teach Learn High Educ 9:3351–3354

Blinder V, Patil S, Eberle C et al (2013) Early predictors of not returning to work in low-income breast cancer survivors: a 5-year longitudinal study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 140:407–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-013-2625-8

de Boer AG, Torp S, Popa A et al (2020) Long-term work retention after treatment for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00862-2

Nekhlyudov L, Walker R, Ziebell R et al (2016) Cancer survivors’ experiences with insurance, finances, and employment: results from a multisite study. J Cancer Surviv 10:1104–1111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0554-3

de Moor JS, Dowling EC, Ekwueme DU et al (2017) Employment implications of informal cancer caregiving. J Cancer Surviv 11:48–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0560-5

Swanberg JE, Vanderpool RC, Tracy JK (2020) Cancer–work management during active treatment: towards a conceptual framework. Cancer Causes Control 31:463–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-020-01285-1

Tangka FKL, Subramanian S, Jones M et al (2020) Insurance coverage, employment status, and financial well-being of young women diagnosed with breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 29:616–624. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0352

Arpey NC, Gaglioti AH, Rosenbaum ME (2017) How socioeconomic status affects patient perceptions of health care: a qualitative study. J Prim Care Community Health 8:169–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131917697439

Ayanian JZ, Kohler BA, Abe T, Epstein AM (1993) The relation between health insurance coverage and clinical outcomes among women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med 329:326–331. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199307293290507

Sowden M, Vacek P, Geller MB (2014) The impact of cancer diagnosis on employment: is there a difference between rural and urban populations? J Cancer Surviv 8:213–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0317-3

Jagsi R, Abrahamse PH, Lee KL et al (2017) Treatment decisions and employment of breast cancer patients: results of a population-based survey. Cancer 123:4791–4799. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30959

van Egmond MP, Duijts SFA, Loyen A et al (2017) Barriers and facilitators for return to work in cancer survivors with job loss experience: a focus group study. Eur J Cancer Care. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12420

Schaeffer E, Srinivas S, Antonarakis ES et al (2021) NCCN guidelines insights: prostate cancer, version 1.2021. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 19(2):134–143. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2021.0008

Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Luo Z et al (2005) Employment outcomes of men treated for prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 97:958–965. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dji171

Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley ST et al (2011) Racial/ethnic differences in job loss for women with breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv 5:102–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-010-0152-8

Gruß I, Hanson G, Bradley C et al (2019) Colorectal cancer survivors’ challenges to returning to work: a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 28:e13044. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13044

Longacre ML, Weber-Raley L, Kent EE (2019) Cancer caregiving while employed: caregiving roles, employment adjustments, employer assistance, and preferences for support. J Cancer Educ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-019-01674-4

U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: New Mexico. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NM. Accessed 13 Dec 2019.

Anderson C (2010) Presenting and evaluating qualitative research. Am J Pharm Educ 74:141. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj7408141

Acknowledgments

This research used the facilities or services of the Behavioral Measurement and Population Sciences (BMPS) Shared Resource, a facility supported by the State of New Mexico and the UNM Cancer Center P30CA118100.

Funding

This work was supported by the American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant HSC-21094 and the University of New Mexico Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA118100. This project was also supported by Contract HHSN261201800014I, Task Order HHSN26100001 from the National Cancer Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the UNM-HSC Institutional Review Board (Study ID: 18-298) and all study procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaffe, S.A., Guest, D.D., Sussman, A.L. et al. A sequential explanatory study of the employment experiences of population-based breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control 32, 1213–1225 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-021-01467-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-021-01467-5