Abstract

Research to date provides only limited insights into the processes of abusive supervision, a form of unethical leadership. Leaders’ vulnerable narcissism is important to consider, as, according to the trifurcated model of narcissism, it combines entitlement with antagonism, which likely triggers cognitive and affective processes that link leaders’ vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision. Building on conceptualizations of aggression as a self-regulatory strategy, we investigated the role of internal attribution of failure and shame in the relationship between leaders’ vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision. We found across three empirical studies with supervisory samples from Germany and the United Kingdom (UK) that vulnerable narcissism related positively to abusive supervision (intentions), and supplementary analyses illustrated that leaders’ vulnerable (rather than grandiose) narcissism was the main driver. Study 1 (N = 320) provided correlational evidence of the vulnerable narcissism-abusive supervision relationship and for the mediating role of the general proneness to make internal attributions of failure (i.e., attribution style). Two experimental studies (N = 326 and N = 292) with a manipulation-of-mediator design and an event recall task supported the causality and momentary triggers of the internal attribution of failure. Only Study 2 pointed to shame as a serial mediator, and we address possible reasons for the differences between studies. We discuss implications for future studies of leaders’ vulnerable narcissism as well as ethical organizational practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Abusive supervision remains a concern for scholars and practitioners in the field of business ethics (Mitchell et al., 2023) and has sometimes been considered the opposite of ethical leadership (e.g., Babalola et al., 2022). Indeed, we would argue that it is a form of unethical leadership as it refers to the “sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact” from leaders directed at their followers (Tepper, 2000, p. 178). By engaging in acts of harm against their followers, abusive supervisors violate deontological (rights and justice) and virtue (moral character) norms in organizations (Ünal et al., 2012). Ample research supports the negative impact that abusive supervision has on followers and organizations (for overviews see Mackey et al., 2017, 2021a, 2021b; Martinko et al., 2013; Schyns & Schilling, 2013). It decreases satisfaction with supervisors (Pircher Verdorfer et al., 2023), fuels turnover intentions (Palanski et al., 2014), and predicts perceptions of workplace aggression more strongly than other unethical forms of leadership do (Cao et al., 2023). The effects of abusive supervision also spill over to others through peer harassment (Bai et al., 2022), gossiping (Decoster et al., 2013), and bullying (Mackey et al., 2018). Responding to calls in the business ethics literature to uncover why leaders engage in (un)ethical behaviors (Babalola et al., 2022) and emphasizing the value of psychological mechanisms (Islam, 2020), we focus on the cognitive and affective processes leading to abusive supervision. We posit that scholars of business ethics must, both from a normative and consequential point of view, continue to create an understanding of the underlying reasons for abusive supervision to contribute to more ethical workplaces.

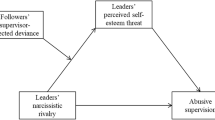

The purpose of our study is to expand the current research with new insights that help us understand why leaders, especially those high in vulnerable narcissism, engage in abusive supervision (see Fischer et al., 2021; Mackey et al., 2017; Tepper et al., 2017; Zhang & Bednall, 2016 for reviews). Previous research illustrates that a multitude of leader characteristics such as traits (e.g., Machiavellianism; De Hoogh et al., 2021), attitudes (e.g., psychological entitlement; Eissa & Lester, 2022), negative emotions (e.g., anxiety; Xi et al., 2022), perfectionism (Guo et al., 2020), and emotional exhaustion (Fan et al., 2020) predict the extent to which leaders engage in abusive supervision. However, when it comes to leader narcissism as a predictor of abusive supervision, the results are mixed. Studies that conceptualized leader narcissism as a unidimensional construct did not show a relationship (Wisse & Sleebos, 2016) or only for some leaders (e.g., with low political skills; Waldman et al., 2018). Studies with multidimensional conceptualizations of narcissism found that leaders’ narcissistic rivalry, but not narcissistic admiration, related positively to abusive supervision (Gauglitz, 2022; Gauglitz & Schyns, 2024). Vulnerable narcissism, however, remains systematically understudied in the work domain. The dearth of research on leaders’ vulnerable narcissism is particularly worrying because findings in a general population provide clear evidence of a vulnerable narcissism–aggression link (Du et al., 2024; Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021).

Psychology offers fruitful avenues for a deeper study of the intra-psychic processes underlying ethical issues in organizations (Babalola et al., 2022; Islam, 2020), and thereby contributes to a broader intellectual base of business ethics research (Greenwood & Freeman, 2017). We build on current developments in the field of personality psychology, and specifically the trifurcated model of narcissism, which suggests that narcissism should be studied hierarchically with two higher order factors, grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. They share a common antagonism component but are unique with respect to extraversion and neuroticism (Crowe et al., 2019; Miller et al., 2021). Vulnerable narcissists are much more problematic as leaders due to their low and contingent self-esteem (Di Pierro et al., 2019; Dinić et al., 2022; Rogoza et al., 2018; Rohmann et al., 2019, 2021). Vulnerable narcissism is equally related to aggression as grandiose narcissism is (Du et al., 2024; Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021), making it a likely antecedent of abusive supervision.

We study leaders’ vulnerable narcissism as a relatively stable personality trait characterized by “a defensive and insecure grandiosity that obscures feelings of inadequacy, incompetence, and negative affect” (Miller et al., 2011, pp. 1013–1014). Vulnerable narcissism differs from “narcissistic leadership” defined as “leaders’ actions [that] are principally motivated by their own egomaniacal needs and beliefs” (Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006, p. 629). It is also different from Vulnerable Narcissistic Leader Behaviour (VNLB; Schyns et al., 2023a, 2023b), that is, “the specific behavioural expression that vulnerable narcissistic leaders show in their daily work life” (p. 817). We disentangle the personality trait of vulnerable narcissism from the leadership behavior, allowing us to investigate leaders’ internal affective and cognitive processes that lead from the trait to its expression.

We base our assumptions on the dynamic self-regulatory processing model of narcissism (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001) and conceptualizations of aggression as a self-regulatory strategy (Denissen et al., 2018; Kruglanski et al., 2023), relating to the argument that vulnerable narcissists show aggression due to frustration and shame (Morf et al., 2011). Shame is a self-conscious emotion that arises through the attribution of failure to stable characteristics of the self (e.g., Tracy & Robins, 2007). Self-conscious emotions have been called moral emotions as they serve moral functions (Tangney et al., 2007a, 2007b). Schaumberg and Tracy (2020) argue that shame and guilt influence unethical behaviors in opposite ways. While guilt serves to improve ethical behavior (e.g., increasing employees’ next-day performance and decreasing enacted incivility; Kim et al., 2024), this may not be the case for shame. Indeed, shame has been linked to aggression. In that way, Tracy and Robins (2007) argue that one of the reasons for narcissistic rage is shame.

Aggression linked to shame serves a purpose in that it can (re-)establish “one’s sense of significance and mattering” (Kruglanski et al., 2023, p. 445) when the individual feels devalued, inferior or exposed, also described as humiliated fury (Lewis, 1971). Previous research illustrates that individuals high in vulnerable narcissism are prone to experience shame (e.g., Di Sarno et al., 2020; Freis et al., 2015), but less is known about why and with which consequences. We argue that leaders high in vulnerable narcissism turn their shame inside out: They direct this painful, self-conscious emotion at a convenient target by abusing their followers (Neves, 2014). We suggest that this process is set in motion by how these leaders attribute: They see the reasons for failure as something negative about themselves (i.e., attribute failure internally) which increases shame.

Attribution theory originating in the works of Heider (1958), Kelley (1973), and Weiner (1985) has been fruitfully applied to the work context (Martinko et al., 2011). Attributions often occur in response to negative trigger events, and when these are attributed internally, the cause is regarded as something negative about the self (e.g., lack of ability or effort; Harvey et al., 2014). In addition, attribution styles are stable, trait-like tendencies toward certain types of attributions (Martinko et al., 2007, 2011). We argue that individuals high in vulnerable narcissism attribute internally both chronically and in response to negative events. These processes might explain why vulnerable narcissism predicts reactive aggression (Vize et al., 2019). Reactive aggression requires a trigger, and for narcissists, the trigger is often a threat directed at the fragile self (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). We, hence, explain abusive supervision as a self-regulatory process: Leaders’ vulnerable narcissism makes them more likely to experience shame because they attribute failure internally and take their negative thoughts about the self out against others.

Our work makes several contributions to the extant business ethics and leadership literature. First, we contribute to a growing body of work that seeks to understand the antecedents of abusive supervision (Fischer et al., 2021; Mackey et al., 2017; Tepper et al., 2017; Zhang & Bednall, 2016), and unethical leadership (Hassan et al., 2023; Mackey et al., 2021a, 2021b), particularly research that emphasizes the unethical implications of vulnerable narcissism in organizations (Gauglitz, 2022; Schyns et al., 2023a, 2023b). Building on recent psychological theories for a better understanding of the underlying issues that spur on abusive supervision, our research disentangles leaders’ vulnerable narcissism as a stable personality trait from leader behavior (Tuncdogan et al., 2017), as traits are not necessarily expressed in behavior (Tett et al., 2021). We provide a new angle to understanding why leaders aggress against their followers that has previously been missed in narcissism, leadership, and ethics research.

Second, we contribute to research into moral emotions in the workplace. Specifically, our work provides further insights into the specific interplay between powerful cognitions and moral emotions in organizations, that is, internal attribution of failure (Martinko et al., 2007) and shame (Daniels & Robinson, 2019). We argue that leaders high in vulnerable narcissism use aggression as a self-regulatory strategy (Denissen et al., 2018; Kruglanski et al., 2023), thereby emphasizing the triggers of leaders’ internal, self-regulatory processes (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001; Morf et al., 2011). Hence, rather than examining other-rated abusive supervision, we ask leaders to indicate to what extent they engaged in or would engage in abusive supervision (for a similar approach see Decoster et al., 2023; and Gauglitz, 2022). A focus on the internal cognitive and affective processes leading to abusive supervision (intentions) will help us to explain how abusive supervision emerges within the individual, thereby contributing to the literature which considers intra-psychic processes as essential to a psychology of ethics (Islam, 2020). Also, in contrast to previous research which focused on general negative affect (e.g., Eissa et al., 2020), we test two specific mechanisms to explain why leaders high in vulnerable narcissism abuse their followers. Understanding these mechanisms offers two potential points for intervention that can contribute to more ethical workplaces.

Finally, we provide supplementary analyses that speak to the uniqueness of our findings for vulnerable narcissism. This contributes to research into different forms of narcissism that aims to better understand the different outcomes related to vulnerable versus grandiose narcissism. We build on the trifurcated model of narcissism, and the distinction between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism (Crowe et al., 2019; Miller et al., 2011, 2021). Our research allows us to shed light on what is shared in terms of vulnerable versus grandiose narcissism and what is unique to (leaders’) vulnerable narcissism. Specifically, in controlling for grandiose narcissism in our analyses, we can draw conclusions about the uniqueness of the effects of vulnerable narcissism. Furthermore, by repeating our analyses with grandiose narcissism, we can also rule out that grandiose narcissism by itself instills the same internal processes leading to abusive supervision as vulnerable narcissism does. These analyses inform business ethics research and practice in that they help disentangle which dimension of narcissism is more problematic for workplace ethics.

Leader Vulnerable Narcissism and Abusive Supervision

Previous studies of the correlates of vulnerable narcissism support that vulnerable narcissists should be predisposed towards abusive supervision. Vulnerable narcissism is positively related to entitlement (Miller et al., 2011, 2018), which predicts abusive supervision (Eissa & Lester, 2022). Vulnerable narcissists are also high in neuroticism (Miller et al., 2011, 2018), and recent results support the positive relationship between angry hostility (an element of neuroticism) and abusive supervision (Fosse et al., 2024). Vulnerable narcissism relates negatively to agreeableness (Miller et al., 2011, 2018), and it has been shown that frustrated leaders are more likely to abuse their subordinates when their agreeableness is low (Eissa & Lester, 2017). Vulnerable narcissists are less likely to experience positive affect and more likely to experience negative affect (Miller et al., 2011), the latter of which has been shown to positively predict abusive supervision (Pan & Lin, 2018).

Individuals high in vulnerable narcissism also show destructive interpersonal behaviors such as anger and rudeness towards others (Miller et al., 2011). Two recent meta-analyses support the relationship between vulnerable narcissism and aggression. A meta-analysis of 437 primary studies shows that vulnerable narcissism relates positively to reactive and proactive aggression (Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021). The authors conclude that “not just individuals who are high in entitlement and grandiose narcissism […] lash out aggressively against others; people who are high in vulnerable narcissism do that too” (Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021, p. 490). In Du et al.’s (2022) meta-analysis of 112 primary studies, the antagonism subdimension (which vulnerable and grandiose narcissism share) related positively to all indices of aggression, and neuroticism (specific to vulnerable narcissism) related positively to reactive and general aggression.

In sum, vulnerable narcissism is positively associated with traits (i.e., high neuroticism and hostility, low agreeableness), emotions (i.e., high negative affect), and behaviors (i.e., high aggression) that predispose leaders high on vulnerable narcissism toward abusive supervision. We therefore expect that vulnerable narcissism relates positively to abusive supervision.

Hypothesis 1.

Leaders’ vulnerable narcissism relates positively to abusive supervision.

Shame, Internal Attribution of Failure, and Abusive Supervision

Self-regulatory theory helps to understand why leaders high in vulnerable narcissism engage in abusive supervision. The fragility of the narcissistic self-concept motivates the individual to strive for external affirmation and to protect themselves from situations that are self-threatening (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). However, these processes differ between individuals high in grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism. Grandiose narcissists aggress against others to establish their superiority, whereas vulnerable narcissists are tormented by inferiority. The aggression of vulnerable narcissists occurs as “an attempt to turn the tables and to right the self, which has been impaired in the shame experience” (Tangney et al., 1992, p. 670). As Morf and colleagues (2011) argue, internal attribution of failure and shame are key elements of vulnerable narcissists’ dynamic self-regulatory processes, and aggression is a way to act out their self-directed frustration.

Shame is a powerful self-conscious emotion because it implies that the whole self is wrong (i.e., “I failed”) as opposed to guilt which centers more on behavior (i.e., “I failed”) (Daniels & Robinson, 2019). Evidence supports that vulnerable narcissism relates positively to shame (r = 0.46 and r = 0.49 in studies by Morf et al., 2017), and that there are differential relationships of vulnerable narcissism and grandiose narcissism with shame-proneness (Schoenleber et al., 2024). Krizan and Johar (2015) demonstrated that vulnerable (but not grandiose) narcissism positively predicted shame, aggressiveness, and poor anger control, distrust of others and angry rumination that in turn related positively to reactive and displaced aggression in general and in response to provocation. In work contexts, Di Sarno et al. (2020) found that workplace events relating to social stress and workload were positively related to shame, particularly for individuals high in vulnerable narcissism. Freis et al. (2015) found that only individuals high (not low) in vulnerable narcissism responded with more shame when they received negative rather than satisfactory feedback for a task on which they believed they had performed well.

These findings illustrate the paradox of vulnerable narcissism: Vulnerable narcissistic individuals harbor thoughts of entitlement, while at the same time doubting their own entitled beliefs and relying on positive enforcement from others to self-regulate (i.e., maintain and restore their fragile self; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001; Morf et al., 2011). We expand the picture on vulnerable narcissism and self-regulation by arguing that leaders high in vulnerable narcissism are looking for a release of their frustration, and therefore aim negative thoughts, emotions, and behaviors at their followers.

Shame and Abusive Supervision

Shame can manifest in unethical behaviors such as withdrawal, avoidance, and attacking others (Murphy & Kiffin-Petersen, 2017). Shame-prone (as opposed to guilt-prone) individuals display maladaptive responses such as anger, hostility, and blaming others for negative events (Tangney et al., 1992). In a correlational study with 240 employees in the United States, Bauer and Spector (2015) found that, contrary to their hypothesis, shame was more strongly related to active than to passive counterproductive work behaviors such as abuse against others (r = 0.46) and social undermining (r = 0.53) compared to withdrawal behaviors (r = 0.36).

Shame is not easily remedied. Leith and Baumeister (1998) suggest that the “only responses that seem to minimize the subjective distress of shame are to ignore the problem, to deny one’s responsibility, to avoid other people, or perhaps to lash out at one’s accusers” (p. 4). They found no relationship between shame and perspective-taking and a negative relationship between shame and interpersonal outcomes.

In sum, it is compelling to suggest that leaders high in vulnerable narcissism act aggressively against others because they perceive their self to be under threat, and they turn the powerful, self-conscious emotion of shame ‘inside-out’ by lashing out against their followers (Neves, 2014). One question is why leaders high in vulnerable narcissism experience shame. We argue that this is due to the way they attribute, that is, that they see the reasons for mistakes as something negative about themselves (i.e., attribute failure internally) which increases shame.

Internal Attribution of Failure and Shame

Failing in organizations is common, and the motivation to understand negative outcomes is high (Smollan & Singh, 2022). We argue that leaders high in vulnerable narcissism show different cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to failure than their less narcissistic counterparts. Attribution theory distinguishes between attributions as “causal explanations for specific events” (Martinko et al., 2007, p. 569), and attribution style, the “tendency to make attributions that are similar across situations” (i.e., a trait-like characteristic; Martinko et al., 2007, p. 569). Locus of causality is the best understood attributional dimension and describes “whether the perceived cause of an outcome is internal or external” (Harvey et al., 2014, p. 130). Internal attribution, in turn, is an antecedent of shame. As Daniels and Robinson (2019) argue, shame arises “when people fall short of important identity-based standards, and make self-threatening attributions for it” (p. 2450), which they call an attribution to “a faulty self” (p. 2453). We posit that leaders high in vulnerable narcissism attribute failure internally both because they have a chronic tendency to do so and because they experience failure-related events as self-threatening. In sum, we expect that internal attribution of failure and subsequent shame can in part explain why leaders high in vulnerable narcissism aggress against their followers in the form of abusive supervision.

Hypothesis 2.

Internal attribution of failure mediates the positive relationship between leaders’ vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision.

Hypothesis 3.

The relationship between leaders’ vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision is mediated by internal attribution of failure and shame in a serial fashion.

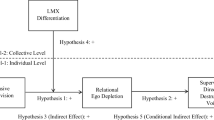

Figure 1 summarizes our research model.

Overview

We conducted three empirical studies with supervisor samples in Germany (Studies 1 and 2) and the UK (Study 3). The first study (N = 320) applies a correlational design with two points of measurement to test how leaders’ vulnerable narcissism relates to general proneness to attribute failure internally (i.e., attribution style) and self-rated abusive supervision. To understand the causality and momentary triggers of the processes involved, we designed two experimental studies (N = 326 and N = 292). In both Study 2 and 3, we assessed narcissism as our independent variable at Time 1 (T1) and, at Time 2 (T2), applied a manipulation-of-mediator design for internal attribution of failure. In Study 2, we linked the internal attribution of failure more clearly to a negative event at work and added shame as a serial mediator. In Study 3, we strengthened our manipulation of internal attribution of failure by using an event recall task. Study 3 also used an improved measurement of shame.

In sum, our study series progresses from initial cross-sectional evidence of the general relationships proposed in the first two hypotheses (Study 1) to a causal analysis of the full model with all three hypotheses and scenario-based testing of momentary triggers (Study 2) to a replication of the causal results with a more rigorous design including increased experimental realism and improved measurement of shame (Study 3). All studies were reviewed and approved by the institution’s ethical review board and participants gave informed consent before taking part in the research.

Study 1

Sample and Procedure

We surveyed supervisors in organizations in Germany at two points in time, approximately ten days apart recruited through Respondi. At T1, participants rated their own vulnerable and grandiose narcissism as well as internal attribution of failure. At T2, participants rated their own abusive supervision and indicated socio-demographic data. At T1, 390 supervisors completed the survey and passed the attention checks to ensure data quality, 320 of whom also completed the survey and passed attention checks at T2 (159 women, 161 men). Supervisors were between 26 and 64 years old (M = 46.06, SD = 9.71), and had between 0.5 and 40 years of supervisory experience (M = 11.21, SD = 8.12). They held positions as team leaders (30.9%), managed departments (38.1%) or business areas (16.6%), or top management team members (12.2%; 2.2% in other positions).

Measurement

Vulnerable Narcissism

We assessed vulnerable narcissism with a 16-item version (Schoenleber et al., 2015) of Pincus et al.’s (2009) Pathological Narcissism Inventory (PNI; α = 0.93) using items from the four subdimensions of contingent self-esteem, hiding the self, devaluing others, and entitlement rage (validated translation by Morf et al., 2017). Participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale from fully disagree (1) to fully agree (7).

Internal Attribution of Failure

Participants rated five negative workplace situations (1 = Nothing to do with me, 7 = Totally due to me; α = 0.64Footnote 1) from the Organizational Attributional Style Questionnaire (OASQ; Kent & Martinko, 2018), which were translated into German and back-translated following standard procedures.

Abusive Supervision

We adapted Tepper’s (2000) abusive supervision scale (α = 0.92; 15 items) using Schilling and May’s (2015) translation to capture self-rated abusive supervision. Participants rated the extent to which they engaged in abusive supervision on a scale from never (1) to very often (7). The adapted items are provided in OSM section IV.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the means, standard deviations, and correlations for Study 1. We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with ML estimation in Mplus Version 8.7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2024). Our hypothesized model fitted the data best (see OSM Section I).

Hypothesis Testing

We ran a hierarchical linear regression in SPSS version 28 with 95% confidence intervals and vulnerable narcissism as the predictor. In line with Hypothesis 1, the results indicated a significant positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision (B = 0.258, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.196, 0.320]). Next, we estimated the mediation model in PROCESS (Hayes, 2018) using Model 4 and 95% confidence intervals. Results in Table 2 show that vulnerable narcissism related positively to internal attribution of failure (B = 0.161, SE = 0.064, p < 0.05, 95%CI [0.035, 0.287]). Internal attribution of failure related positively to abusive supervision (B = 0.064, SE = 0.027, p < 0.05, 95%CI [0.011, 0.118]). The indirect relationship was significant (B = 0.010, SE = 0.007, 95%CI [0.0002, 0.0274]), supporting Hypothesis 2.

Robustness Checks

Given the positive correlation between vulnerable narcissism and grandiose narcissism in our data (r = 0.69), we repeated all analyses with grandiose narcissism as a covariate and found that the relationships remained similar. The results did not replicate for grandiose narcissism as a predictor (for details see OSM Section I).

Discussion

The first study showed that leaders’ vulnerable narcissism related positively to self-rated abusive supervision. The general tendency to attribute failure internally mediated this relationship. However, the study has several clear limitations. First, although not out of range for situation-based measurement, the internal attribution of failure measure was low in internal consistency. It also assessed attribution style rather than attributions related to a specific event. Second, we did not provide causal evidence of the predicted relationships. Finally, we did not test the role of shame as a sequential mediator. We next designed an experiment to examine the causal role of internal attribution of failure in relation to a specific trigger event, using an improved measure of attribution of failure for manipulation check, and testing shame as a sequential mediator.

Study 2

Sample and Procedure

We surveyed supervisors from organizations in Germany at two points in time, approximately ten days apart, recruited through Respondi. Only individuals who had not taken part in the previous study were invited. At T1, participants rated their vulnerable and grandiose narcissism. At T2, we implemented the manipulation-of-mediator design. At T1, 460 supervisors responded to the survey, 431 of whom provided complete data and passed attention checks to ensure data quality (217 women, 214 men). At T2, 326 supervisors provided complete data and passed attention checks. Participants were between 21 and 72 years old (M = 44.50, SD = 11.01) and had between one and 45 years of supervisory experience (M = 12.96, SD = 9.07). Participants held positions as team leader (39.5%), led departments (42.6%) or business areas (26.1%), and were top management team members (15.0%; 4.6% in other positions).

Manipulation-of-Mediator Design

The manipulation-of-mediator design tests the causal effect of the mediator on the dependent variable by comparing the relationship between independent and dependent variables under different conditions of the mediator (MacKinnon & Pirlott, 2015; Pirlott & MacKinnon, 2016). When constraining the variance of the mediator in the experimental condition relative to when the mediator varies freely (i.e., the control condition), the predicted relationships between independent variable and outcomes should not occur (or only to a lesser extent; for a succinct overview of the manipulation-of-mediator design see Highhouse and Brooks (2021), and for studies that employed it see Chen et al., 2021; Lamer et al., 2022; Schyns et al., 2023a, 2023b).

The manipulation-of-mediator design was implemented in our second study as follows: Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: internal attribution of failure, external attribution of failure, or no attribution of failure (control). In the internal attribution condition, we prevented the mediator from varying freely, thereby blocking the hypothesized mediating mechanism from operating. Participants envisioned a scenario in which they were the head of a sales and marketing department in a mid-sized company in the technology sector. The department consisted of five teams, each supervised by a team leader. The team leaders were the participant’s direct subordinates. We informed participants that a team in their department had failed to win a significant bid and that the failure was their fault (internal attribution) or the team leader’s (i.e., the participant’s subordinate’s) fault (external attribution). In the control condition, we allowed the mediator to vary freely by not providing any information about whose fault it was. Specifically, in the internal attribution condition, an email from a dissatisfied client stressed that the failure was the participant’s own fault. In the external attribution condition, an email from the dissatisfied client stressed that it was the team leader’s fault. In the control condition, participants did not receive information about whose fault it was that the team failed to win the bid.

Following the logic of the manipulation-of-mediator design, Hypothesis 2 is supported if there is a positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision intentions in the control condition and no (or a weaker) positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision intentions in the internal attribution condition. Hypothesis 3 is supported if there is a positive indirect relationship between vulnerable narcissism, shame, and abusive supervision intentions in the control condition and no (or a weaker) positive indirect relationship between vulnerable narcissism, shame, and abusive supervision intentions in the internal attribution condition.

The external attribution condition was a comparison condition, which also prevented the mediator from varying freely, thereby restricting the hypothesized mediating mechanism. We did not have specific predictions for this condition. Since we are comparing conditions (control, internal, and external attribution of failure) to test the mediation effect of internal attribution of failure, we conducted a moderated mediation model with experimental conditions serving as the categorical moderator (PROCESS version 4.0, Model 8). We measured shame and abusive supervision intentions in response to the experimental scenario and conducted a manipulation check.

Measurement

For vulnerable narcissism (α = 0.94) and abusive supervision (α = 0.91) adapted to our scenario (e.g., “I would tell [the subordinate] that their thoughts or feelings are stupid”), we used the same measures as in Study 1.

Shame

We used two items to measure shame (r = 0.63) in response to the scenario (“In this situation I would think about quitting” and “In this situation I would feel incompetent”) adapted from Tangney et al., (2007a).Footnote 2

Manipulation Check

We used the German translation (Grassinger & Dresel, 2017) of three items (α = 0.81) from the Revised Causal Dimension Scale (CDS II; McAuley et al., 1992) for the manipulation check (e.g., “Were the reasons why this mistake happened… something about you – something about others”, reverse coded).

Results

We reported the means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables for Study 2 in the OSM (see Section II).

Manipulation Check

The manipulation check indicated significantly higher levels of internal (vs. external) attribution of failure in the internal attribution condition (M = 5.16, SD = 1.26; 95%CI [4.932, 5.383]) than in the external attribution condition (M = 3.53, SD = 1.24; 95%CI [3.302, 3.761]) and the control condition (M = 4.06, SD = 1.09; 95%CI [3.838, 4.289]), F(2,323) = 51.682, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.242. We concluded that the manipulation was successful.

Hypothesis Testing

We estimated a moderated mediation model in PROCESS version 4.0 (Hayes, 2017) using Model 8 with 5,000 bootstrap samples and 95% confidence intervals to regress abusive supervision intentions on vulnerable narcissism, including the three groups (i.e., internal attribution, external attribution, control) as the categorical moderator, shame as the mediator, and abusive supervision intentions as the outcome. Table 3 summarizes the means and standard deviations by condition. Table 4 summarizes the direct and indirect effects.

Supporting Hypothesis 1, a positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision intentions emerged (B = 0.290, SE = 0.075, p < 0.001, 95%CI [0.142, 0.438]) across the three experimental conditions, as shown in Table 4. Hypothesis 2 (i.e., internal attribution of failure mediates the positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision intentions) is supported if there is a positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision intentions in the control condition and no (or a weaker) positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision intentions emerges in the internal attribution condition.

As shown in Table 4, the effect of vulnerable narcissism on abusive supervision intentions was stronger in the control condition (B = 0.424, SE = 0.075, 95%CI [0.277, 0.571]) than in the internal attribution condition (B = 0.290, SE = 0.075, 95%CI [0.142, 0.438]), although not significant, supporting Hypothesis 2. That is, when the mediator varied freely (i.e., control condition), the positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision intentions was higher than when the mediator was blocked (i.e., internal attribution condition). To note that there was a significant effect in the external attribution condition (B = 0.287, SE = 0.076, 95%CI [0.139, 0.436]).

Hypothesis 3 (i.e., internal attribution of failure and shame serially mediate the positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision intentions) is supported if there is a positive indirect relationship between vulnerable narcissism, shame, and abusive supervision intentions in the control condition and no (or a weaker) positive indirect relationship between vulnerable narcissism, shame, and abusive supervision intentions emerges in the internal attribution condition. The conditional indirect relationship between vulnerable narcissism, shame, and abusive supervision intentions was significant in all three conditions. As shown in Table 4, the indirect effect was stronger in the control condition (B = 0.058, SE = 0.023, 95%CI [0.015, 0.103]) compared to the internal attribution condition (B = 0.029, SE = 0.170, 95%CI [0.001, 0.068]), although not significant, supporting Hypothesis 3. That is, when the mediator varied freely (i.e., control condition), the positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism, shame, and abusive supervision intentions was higher than when the mediator was blocked (i.e., internal attribution condition). To note that the external attribution condition resulted in a small effect (B = 0.064, SE = 0.026, 95%CI [0.012, 0.108]).

Robustness Checks

Again, we repeated all analyses with grandiose narcissism as a covariate and found that the relationships remained comparable. Again, the results did not replicate for grandiose narcissism (for details see OSM Section II).

Discussion

In the second study, we found evidence to confirm the positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision intentions (Hypothesis 1). The findings suggested that internal attribution of failure may function as a mediator (Hypothesis 2), and of the serial mediation through internal attribution of failure and shame (Hypothesis 3), although the evidence was not conclusive. There are several clear limitations of this study: The analysis following a manipulation-of-mediator design suggested that the mediation in the internal attribution condition was not blocked, just reduced. The manipulation of internal attribution of failure was based on a scenario that suggested to participants what the reason for the failure was (i.e., it did not capture their own attributions, but triggered an attribution based on external information). Although the manipulation check showed that the participants’ subsequent attribution followed as intended, we did not capture an actual event that they had experienced and their own, independent attribution and behavior in response. Finally, the two-item shame measure is a concern, although we provided additional information about convergent and divergent validity. We designed a final study to re-examine the causal role of internal attribution of failure and shame as mediating mechanisms of the relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision with an event recall task and an improved measure of shame.

Study 3

Sample and Procedure

We surveyed supervisors from different organizations in the UK at two points in time, approximately ten days apart, recruited through Prolific. At T1, participants rated their vulnerable and grandiose narcissism. At T2, we implemented an event recall task with a manipulation-of-mediator design. At T1, 362 supervisors responded to the survey, 357 of whom provided complete data and passed attention checks to ensure high data quality. At T2, 292 supervisors (146 women, 146 men) provided complete data and passed attention checks. Participants were between 19 and 66 years old (M = 34.62, SD = 9.18) and had between less than one and 30 years of supervisory experience (M = 5.53, SD = 5.42). Participants held positions as team leader (61.6%), managed departments (19.9%), were area managers (3.4%), or top management team members (10.6%; 10.6% in other positions).

Manipulation-of-Mediator Design and Event Recall

We followed the same logic for the manipulation-of-mediator design as in Study 2. Different from Study 2, we employed an event recall task based on Grube et al.’s (2008) adaptation of the day reconstruction method (Kahneman et al., 2004). As in Study 2, participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: internal attribution of failure, external attribution of failure or no attribution of failure (control condition). We asked participants to recall one specific mistake that had happened recently and involved one of their subordinates. In the internal attribution condition, participants recalled a serious mistake that involved a subordinate and that they were personally responsible for. In the external attribution condition, participants recalled a serious mistake that involved a subordinate and that their subordinate was responsible for. In the control condition, participants recalled a serious mistake that involved a subordinate, and no further instructions were given as to who was responsible for it. The manipulations for each condition are provided in OSM section V. Participants were then asked to recall and describe the event in as much detail as possible, followed by a series of questions to assess shame and abusive supervision toward the subordinate involved in the mistake.

The same logic for the support of hypotheses outlined in Study 2 applies to Study 3. Again, we did not have specific predictions for the external attribution condition. Since we are comparing conditions (control, internal, and external attribution of failure) to test the mediation effect of internal attribution of failure, we conducted a moderated mediation model with experimental conditions serving as the categorical moderator (PROCESS version 4.0, Model 8). We measured shame and abusive supervision in response to the experimental scenario and conducted a manipulation check.

Measurement

For vulnerable narcissism (α = 0.89) and abusive supervision (α = 0.91), we used the same measures as in Study 2.

Shame

We adapted five items from Tangney et al., (2007a) to measure shame (r = 0.87) in response to the event recall task (i.e., To what extent did you experience the following emotions when this mistake happened? “I thought about quitting my job”, “I felt incompetent”, “I felt stupid”, I felt as if I wanted to hide”, I felt ashamed”).

Manipulation Check

We adapted six items from the Revised Causal Dimension Scale (CDS II; McAuley et al., 1992). Three items measured internal attribution (α = 0.85) (e.g., “Were the reasons why this mistake happened… something about you – something about others”, reverse coded) and three items measured external attribution (α = 0.79) (e.g., “Were the reasons why this mistake happened… something about your subordinate – something about others”, reverse coded).

Results

We reported the means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables for Study 3 in OSM section III.

Manipulation Check

The manipulation check indicated significantly higher levels of internal attribution in the internal attribution condition (M = 4.52, SD = 1.38; 95%CI [4.243, 4.807]) than in the external attribution condition (M = 2.48, SD = 1.15; 95%CI [2.200, 2.749]) and the control condition (M = 2.91, SD = 1.60; 95%CI [2.631, 3.180]), F(2,289) = 58.037, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.287. Similarly, the manipulation check indicated significantly higher levels of external attribution in the external attribution condition (M = 5.22, SD = 1.35; 95%CI [4.944, 5.494]) than in the internal attribution condition (M = 3.55, SD = 1.29; 95%CI [3.264, 3.828]) and the control condition (M = 4.61, SD = 1.52; 95%CI [4.338, 4.888]), F(2,289) = 35.680, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.198. We concluded that the manipulation was successful.

Hypothesis Testing

We estimated a moderated mediation model in PROCESS version 4.0 (Hayes, 2018) using Model 8 with 5,000 bootstrap samples and 95% confidence intervals to regress abusive supervision on vulnerable narcissism, including the three groups (i.e., internal attribution, external attribution, control) as the categorical moderator, shame as the mediator, and abusive supervision as the outcome. Table 5 summarizes the means and standard deviations by condition for dependent variables. Table 6 summarizes the direct and indirect effects.

Supporting Hypothesis 1, a positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision emerged (B = 0.149, SE = 0.059, p < 0.05, 95%CI [0.033, 0.265]) across the three experimental conditions, as shown in Table 6.

Hypothesis 2 (i.e., internal attribution of failure mediates the positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision) is supported if there is a positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision in the control condition and no (or a weaker) positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision emerges in the internal attribution condition. As shown in Table 6, the effect of vulnerable narcissism on abusive supervision emerged in the control condition (B = 0.149, SE = 0.059, 95%CI [0.033, 0.265]), whereas this effect became non-significant in the internal attribution condition (B = 0.060, SE = 0.063, 95%CI [−0.065, 0.185]), supporting Hypothesis 2. That is, when the mediator varied freely (i.e., control condition), the positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision occurred, but it did not occur when the mediator was blocked (i.e., internal attribution condition). To note that there was no effect in the external attribution condition (B = 0.094, SE = 0.060, 95%CI [−0.023, 0.211]).

Hypothesis 3 (i.e., internal attribution of failure and shame serially mediate the positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision) is supported if there is a positive indirect relationship between vulnerable narcissism, shame, and abusive supervision in the control condition and no (or a weaker) positive indirect relationship between vulnerable narcissism, shame, and abusive supervision in the internal attribution condition. However, contrary to Hypothesis 3, estimates of the conditional indirect relationship between vulnerable narcissism, shame, and abusive supervision suggested that this relationship was not significant in the control condition (B = 0.007, SE = 0.019, 95%CI [−0.029, 0.049]), whereas it was significant in the internal attribution condition (B = 0.053, SE = 0.030, 95%CI [0.005, 0.122]), as shown in Table 6. That is, when the mediator varied freely (i.e., control condition), the predicted positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism, shame, and abusive supervision did not occur. To note that the external attribution condition resulted in a small effect (B = 0.038, SE = 0.017, 95%CI [0.009, 0.077]).

Robustness Checks

Again, we repeated all analyses with grandiose narcissism as a covariate and found that the relationships remained similar. Again, the results did not replicate for grandiose narcissism (for details see OSM Section III).

Discussion

Our final study confirmed the positive relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision with an event recall task that increased experimental realism. We found that leaders’ internal attribution of failure mediated this relationship. However, this study failed to support the sequential mediation through shame. Some limitations of this study require acknowledgment and can inform future research. Although our manipulation of the attribution of failure was successful, we cannot exclude that memory biases may have affected the event recall (see below for a more detailed discussion of mnemic neglect; Sedikides & Green, 2009). Therefore, the question of whether shame is the reason why vulnerable narcissists’ internal attribution of failure results in abusive supervision must be further examined and tested vis-à-vis alternative explanations.

Discussion

We set out to make three contributions to the business ethics and leadership literature: The first aim of our research was to shed light on leaders’ vulnerable narcissism as an antecedent of abusive supervision, using current developments in psychology, specifically the trifurcated model of narcissism, to advance the understanding of predictors of this unethical form of leadership. Second, we sought to examine the interplay between internal cognitive and affective processes, specifically internal attribution of failure and the moral emotion of shame, as intra-psychic processes that may explain the relationship (Islam, 2020). Third, we tested the uniqueness of our findings for leaders’ vulnerable narcissism, ruling out that the same processes may hold for grandiose narcissism.

In relation to the first contribution, across three empirical studies with different designs, namely a survey study, and two experimental manipulation-of-mediator studies, one of which used scenarios while the other one prompted an event recall, we found compelling evidence of the positive relationship between leaders’ vulnerable narcissism and their abusive supervision (intentions). We derived our assumptions from the dynamic self-regulatory processing model of narcissism (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001) and the idea that vulnerable narcissists act out in frustration because they feel inferior and ashamed of themselves (Morf et al., 2011). We assessed abusive supervision from the leader’s point of view (see also Decoster et al., 2023; Gauglitz, 2022) in three different ways: as self-rating, as intentions, and as a recollection of past behavior. The relationship between vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision (intentions) was stable across those different types of assessments. Our work therefore contributes to a new stream of research that examines the abuser’s experience (e.g., Priesemuth & Bigelow, 2020) with the potential to expand current views of unethical leadership in the business ethics literature (Babalola et al., 2022).

In relation to the second contribution, emphasizing the importance of intra-psychic processes for a psychology of ethics (Islam, 2020), our research sheds light on possible cognitive and affective mechanisms linking leaders’ vulnerable narcissism to abusive supervision (intentions). We found that internal attribution of failure, in the form of attribution styles and momentary attribution in response to events, in part explains the relationship between leaders’ vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision (intentions). This finding emphasizes the paradoxical nature of vulnerable narcissism as set out in the dynamic self-regulatory processing model by Morf and Rhodewalt (2001): Even though vulnerable narcissists crave approval from others to stabilize their fragile self, they lack the ability to form positive relationships or to show constructive leader behavior (Schyns et al., 2023a, 2023b) and instead abuse and alienate followers. Although beyond the remit of our study, it is not unthinkable that by abusing others these leaders go even deeper down the rabbit hole of negative self-views and social isolation. Future research could test whether vulnerable narcissism aggravates the relationship between abusive supervision and social worth (Priesemuth & Bigelow, 2020).

In relation to the third contribution, our results confirmed that vulnerable narcissism is the more problematic dimension of narcissism when it comes to unethical leadership as a comparison of our results for vulnerable narcissism with results for grandiose narcissism showed. Indeed, while there is overlap in terms of the antagonistic facet common to both dimensions of narcissism, vulnerable narcissism remains the better predictor of abusive supervision (intentions). Thus, we add to the small yet growing body of studies that are concerned with leaders’ vulnerable narcissism (Schyns, Braun, et al., 2023; Schyns, Gauglitz, et al., 2023; Schyns et al., 2022). Our findings corroborate evidence of the risks that leaders with a fragile self can pose to others from an ethics perspective (Gauglitz, 2022; Neves, 2014; Schyns et al., 2023a, 2023b).

Notwithstanding the contributions of our work, questions remain regarding the role of shame in the relationship between leaders’ vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision. While Study 2 provided initial support for shame as a sequential mediator, we could not replicate this result in Study 3. This might be due to different methodological designs applied in these two studies. While in Study 2, participants reacted to a hypothetical scenario, the third study asked participants to report their memories of an event that they had experienced as a leader. Participants might have recalled events that were less shameful, thus making it less likely to find an indirect effect of shame in Study 3. Mnemic neglect posits that individuals tend to recall negative self-threatening feedback less well than self-affirming feedback (Sedikides & Green, 2009). We recommend examining this memory bias in future research on vulnerable narcissism.

Another potentially relevant difference between our studies was that in Study 2, participants were told who was responsible for the event while in Study 3, they were asked to select personally experienced events from memory. It is possible that changing the agent who makes the attribution (i.e., others in Study 2 versus the leader in Study 3) contributed to the different results. First, in actual events, not only one person but often several individuals contribute to an issue. In Study 2, participants were told that they were responsible for the failure, leaving less room for ambiguity. However, in Study 3, participants were asked to recall an event. Considering vulnerable narcissists are prone to devaluing others, even leaders who were asked to recall an event that they were responsible for might (also to deflect strong, self-threatening feelings about the memory) think that who is to blame for the failure is more ambiguous, in that others have contributed to it.

Relatedly, applying the displaced aggression framework of abusive supervision (Hoobler & Brass, 2006), Neves (2014) showed that abusive supervisors are more likely to aggress against subordinates with lower core self-evaluation and coworker support. Perhaps vulnerable narcissistic leaders take their shame out against convenient targets (rather than any of their followers). In the scenario experiment (Study 2), participants indicated abusive supervision intentions toward a fictitious target. However, when remembering actual abuse directed at one of their followers (Study 3), leaders might have internally justified their behavior and thus felt less ashamed by thinking that the respective follower deserved the abuse. Future research should investigate how far justification via follower characteristics might influence the internal cognitive and affective processes of vulnerable narcissistic leaders. It would also be interesting for future research to differentiate types of triggers. A recent meta-analysis suggests that narcissism relates more strongly to aggression with an affiliation-related provocation (e.g., disliking, social exclusion) rather than a status-related provocation (Kjærvik & Bushman, 2021). Perhaps the shame–abusive supervision link would be stronger if the failure was in an interpersonal rather than a task-related domain (as in Study 2).

Limitations and Future Research

Similar to other studies (Decoster et al., 2013; Gauglitz, 2022), we assessed abusive supervision from the leader’s point of view in three different ways (self-rating, intentions, recall). While this approach avoids issues related to follower ratings of abusive supervisory behavior (see Hansbrough et al., 2015 for a critical discussion of follower ratings) and is appropriate for studying internal processes, it is subject to ego-centric biases. We addressed this issue by using different designs to invoke leader responses, and thus being more confident that the identified relationships hold. However, future research could relate leader self-rated abusive supervision to follower-rated abusive supervision. It would, in this case, also be interesting to differentiate between more active (e.g., abusive supervision) or more passive (e.g., laissez-faire) forms of negative leadership (e.g., Klasmeier et al., 2022) to examine if leader self-rated abusive supervision really translates into active or indeed passive forms of abuse in line with the idea that vulnerable narcissists might withdraw from social interactions. While individuals high in vulnerable narcissism are unforgiving of others’ mistakes (Lannin et al., 2014), they might spend more time ruminating (Rogoza et al., 2022) or ‘daydreaming’ (Ghinassi et al., 2023) about abusive behaviors than showing them, perhaps using less overt forms of abuse when they do (Mitchell & Ambrose, 2007). We thus encourage future studies to include both leader and follower perceptions of abusive supervision and to differentiate between active and passive forms of abusive supervision.

While in Study 1, we assessed attribution style, in Study 2, the internal attribution was triggered by a specific, experimentally manipulated event. In Study 3, participants recalled an event. While we asked participants to describe the event to make their memory more vivid and strengthen the manipulation, we did not analyze the recalled events. It is possible that different types of events triggered different responses. Future research could conduct qualitative studies to better understand what exactly triggers the internal attribution of failure and perhaps shame in vulnerable narcissistic leaders to further help organizations break the link between this personality trait and its expression.

In addition, experience sampling methodology (ESM) could be fruitfully applied to replicate and expand our results on the underlying processes linking leaders’ vulnerable narcissism and abusive supervision. ESM studies can provide a deeper understanding of momentary experiences in the workplace, and current results show that factors such as time pressure trigger day-to-day abusive supervisory behavior (Zhang & Jia, 2023). The real-time ESM assessment would enable future research to overcome some of the limitations of scenarios or event recall in experiments. It would, for example, be interesting to investigate in how far working conditions such as time pressure interact with vulnerable narcissism to predict internal attribution of failure, shame, and unethical behavior. Indeed, time pressure could aggravate these issues as leaders might lack the time to reflect on possible longer-term consequences of their abusive behavior.

Furthermore, the aggression literature distinguishes between different forms and purposes of aggression, such as reactive aggression (i.e., hostile, impulsive, emotion-driven) and proactive aggression (i.e., instrumental, pre-meditated; Bushman & Anderson, 2001). Recent meta-analyses suggest that vulnerable narcissism relates to reactive aggression (Du et al., 2022). While we believe that reactive aggression may serve to stabilize these leaders’ self-esteem after self-threatening events by devaluing others (Morf et al., 2011), future research should test this assumption directly to understand vulnerable narcissists’ motivations when they act aggressively.

In addition, while we were interested in abusive supervision, there are many ways in which leaders engage in unethical leadership, and these should be considered as outcomes of leaders’ vulnerable narcissism. There are also possible boundary conditions, which go beyond the micro-level dynamics between leaders and followers that we have considered here (e.g., Hassan et al., 2023, for different levels of boundary conditions of unethical leadership). It would also be interesting to assess subsequent follower outcomes (e.g., counterproductivity; Braun et al., 2018). Followers may engage in retaliation to ‘get even’ with their abusive supervisors (e.g., restore justice perceptions; Liang et al., 2022), particularly when they see the leader as responsible for the event. As a result, leader and follower behavior could result in a vicious cycle as it further exacerbates the threat to vulnerable narcissists’ self-esteem, making it interesting for future research to investigate reciprocal relationships between abusive supervision and follower behavior.

Practical Implications

Our research suggests that it is crucial for organizations to address leaders’ vulnerable narcissism as a precursor to unethical behavior. First, organizations have a duty of care to their employees and should protect them from abusive supervision. Ideally, organizations should avoid hiring or promoting vulnerable narcissists into leadership positions to prevent unethical behavior and harm to followers (Mackey et al., 2018; Park et al., 2018, 2019; Wang et al., 2015) as well as negative downstream consequences (e.g., turnover intentions; Palanski et al., 2014). However, implementing narcissism diagnostics in hiring processes might pose legal problems in many countries as it could be construed as discriminating based on a stable personality trait. It may be more suitable to address this issue in promotion decisions, when evidence of leaders’ unethical behavior (such as abusive supervision) should be prohibitive of further progression within the organization.

Second, knowing that vulnerable narcissists are prone to attribute failure internally and that this attribution triggers abusive supervision, organizations should make sure that failure is analyzed thoroughly and constructively to avoid (self-) blaming. Coaching approaches can help leaders negotiate the failure experience, including the recognition that failure has occurred, managing their emotions, and facilitating the ability to learn which helps increase their effectiveness in the future (Newton et al., 2008). Similarly, organizations can encourage a culture that focuses away from blaming individuals but rather regards failure as a precursor to learning (e.g., mastery climates). Doing so might help vulnerable narcissistic leaders break the link between negative events and their cognitive response leading to abusive supervision.

In this sense, third, it is important to keep in mind that leaders are often scapegoats for issues in organizations and their influence on success and failure tends to be overestimated (Meindl, 1995). Organizations can, on the one hand, try to ensure that scapegoating is minimized and, on the other hand, increase these leaders’ self-awareness and meta-skills when they deal with failure. Such interventions could either prevent internal attribution processes in the first place or help leaders break the link between their initial reactions and abusive supervision by strengthening personal resources to deal with negative feedback in a more adaptive way.

Conclusion

While largely disregarded in organizational research to date, vulnerable narcissism represents a considerable risk factor in organizations because it facilitates unethical behavior. This research advances the understanding of leaders’ vulnerable narcissism as a predictor of abusive supervision and the role of leaders’ attributing failure internally. We hope to inspire future business ethics research for a more differentiated understanding of the intra-psychic processes linked to leaders’ vulnerable narcissism to protect followers and organizations from its unethical consequences.

Data availability

Data is available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Notes

The OASQ asks participants to indicate their answers in response to specific situations rather than rating general attitudes or behaviors as is common in survey measures. As a result, it has been argued that internal consistency indices may not fully reflect the OASQ’s reliability (Martinko et al., 2018). The OASQ’s internal consistency in our study, while not ideal and lower compared to common reliability standards, aligns with previous results for a smaller subset of situations (α = .66 for internal/external attributions in three situations; Martinko et al., 2018).

We acknowledge the limitations of the two-item shame measure. In Study 2, we additionally included a measurement of participants’ chronic shame. We asked participants to indicate two separate responses to five negative work-related situations from the Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA-3 short; Tangney et al., 2007a), with one response representing shame and one representing guilt, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely). The correlation between the two-item shame measure and chronic shame was r = .40 (p < .001) and chronic guilt was r = -.01 (p = .92), supporting the convergent and divergent validity.

References

Babalola, M. T., Bal, M., Cho, C. H., Garcia-Lorenzo, L., Guedhami, O., Liang, H., Shailer, G., & van Gils, S. (2022). Bringing excitement to empirical business ethics research: Thoughts on the future of business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 180(3), 903–916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05242-7

Bai, Y., Lu, L., & Lin-Schilstra, L. (2022). Auxiliaries to abusive supervisors: The spillover effects of peer mistreatment on employee performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 178(1), 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04768-6

Bauer, J. A., & Spector, P. E. (2015). Discrete negative emotions and counterproductive work behavior. Human Performance, 28(4), 307–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2015.1021040

Braun, S., Aydin, N., Frey, D., & Peus, C. (2018). Leader narcissism predicts malicious envy and supervisor-targeted counterproductive work behavior: Evidence from field and experimental research. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(3), 725–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3224-5

Bushman, B. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2001). Is it time to pull the plug on hostile versus instrumental aggression dichotomy? Psychological Review, 108(1), 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.1.273

Cao, W., Li, P., Van Der Wal, C., & R., & W. Taris, T. (2023). Leadership and workplace aggression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 186(2), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05184-0

Chen, S., Binning, K. R., Manke, K. J., Brady, S. T., McGreevy, E. M., Betancur, L., Limeri, L. B., & Kaufmann, N. (2021). Am I a science person? A strong science identity bolsters minority students’ sense of belonging and performance in college. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(4), 593–606. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220936480

Crowe, M. L., Lynam, D. R., Campbell, W. K., & Miller, J. D. (2019). Exploring the structure of narcissism: Toward an integrated solution. Journal of Personality, 87(6), 1151–1169. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12464

Daniels, M. A., & Robinson, S. L. (2019). The shame of it all: A review of shame in organizational life. Journal of Management, 45(6), 2448–2473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318817604

Decoster, S., Camps, J., Stouten, J., Vandevyvere, L., & Tripp, T. M. (2013). Standing by your organization: The impact of organizational identification and abusive supervision on followers’ perceived cohesion and tendency to gossip. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(3), 623–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1612-z

Decoster, S., De Schutter, L., Menges, J., De Cremer, D., & Stouten, J. (2023). Does change incite abusive supervision? The role of transformational change and hindrance stress. Human Resource Management Journal, 33(4), 957–976. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12494

Denissen, J. J., Thomaes, S., & Bushman, B. J. (2018). Self-regulation and aggression: Aggression-provoking cues, individual differences, and self-control strategies. In K. de Ridder, D. Adriaanse, & M. Fujita (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of self-control in health and well-being (pp. 330–339). Routledge.

De Hoogh, A. H. B., Den Hartog, D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2021). Showing one’s true colors: Leader machiavellianism, rules and instrumental climate, and abusive supervision. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(7), 851–866. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2536

Dinić, B. M., Sokolovska, V., & Tomašević, A. (2022). The narcissism network and centrality of narcissism features. Current Psychology, 41(11), 7990–8001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01250-w

Du, T. V., Lane, S. P., Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2024). Momentary assessment of the relations between narcissistic traits, interpersonal behaviors, and aggression. Journal of Personality, 92(2), 405–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12831

Du, T. V., Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2022). The relation between narcissism and aggression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality, 90(4), 574–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12684

Eissa, G., & Lester, S. W. (2017). Supervisor role overload and frustration as antecedents of abusive supervision: The moderating role of supervisor personality. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(3), 307–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2123

Eissa, G., & Lester, S. W. (2022). A moral disengagement investigation of how and when supervisor psychological entitlement instigates abusive supervision. Journal of Business Ethics, 180(2), 675–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04787-3

Eissa, G., Lester, S. W., & Gupta, R. (2020). Interpersonal deviance and abusive supervision: The mediating role of supervisor negative emotions and the moderating role of subordinate organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(3), 577–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04130-x

Fan, X. L., Wang, Q. Q., Liu, J., Liu, C., & Cai, T. (2020). Why do supervisors abuse subordinates? Effects of team performance, regulatory focus, and emotional exhaustion. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(3), 605–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12307

Fischer, T., Tian, A. W., Lee, A., & Hughes, D. J. (2021). Abusive supervision: A systematic review and fundamental rethink. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(6), 101540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101540

Fosse, T. H., Martinussen, M., Sørlie, H. O., Skogstad, A., Martinsen, Ø. L., & Einarsen, S. V. (2024). Neuroticism as an antecedent of abusive supervision and laissez-faire leadership in emergent leaders: The role of facets and agreeableness as a moderator. Applied Psychology, 73(2), 675–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12495

Freis, S. D., Brown, A. A., Carroll, P. J., & Arkin, R. M. (2015). Shame, rage, and unsuccessful motivated reasoning in vulnerable narcissism. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34(10), 877–895. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2015.34.10.877

Gauglitz, I. K. (2022). Different forms of narcissism and leadership. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie, 230(4), 321–324. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000480

Gauglitz, I. K., & Schyns, B. (2024). Triggered abuse: How and why leaders with narcissistic rivalry react to follower deviance. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05579-7

Ghinassi, S., Fioravanti, G., & Casale, S. (2023). Is shame responsible for maladaptive daydreaming among grandiose and vulnerable narcissists? A general population study. Personality and Individual Differences, 206, 112122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112122

Grassinger, R., & Dresel, M. (2017). Who learns from errors on a class test? Antecedents and profiles of adaptive reactions to errors in a failure situation. Learning and Individual Differences, 53, 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.11.009

Greenwood, M., & Freeman, R. E. (2017). Focusing on ethics and broadening our intellectual base. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3414-1

Grube, A., Schroer, J., Hentzschel, C., & Hertel, G. (2008). The event reconstruction method: An efficient measure of experience-based job satisfaction. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 81(4), 669–689. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317907X251578

Guo, L., Chiang, J. T. J., Mao, J. Y., & Chien, C. J. (2020). Abuse as a reaction of perfectionistic leaders: A moderated mediation model of leader perfectionism, perceived control, and subordinate feedback seeking on abusive supervision. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(3), 790–810. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12308

Harvey, P., Madison, K., Martinko, M., Crook, T. R., & Crook, T. A. (2014). Attribution theory in the organizational sciences: The road traveled and the path ahead. Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(2), 128–146. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0175

Hassan, S., Kaur, P., Muchiri, M., Ogbonnaya, C., & Dhir, A. (2023). Unethical leadership: Review, synthesis and directions for future research. Journal of Business Ethics, 183(2), 511–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05081-6

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Wiley.

Highhouse, S., & Brooks, M. E. (2021). A simple solution to a complex problem: Manipulate the mediator! Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 14(4), 493–496. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2021.117

Hoobler, J. M., & Brass, D. J. (2006). Abusive supervision and family undermining as displaced aggression. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1125–1133. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1125

Islam, G. (2020). Psychology and business ethics: A multi-level research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics, 165(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04107-w

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science, 306(5702), 1776–1780. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1103572

Kelley, H. H. (1973). The processes of causal attribution. American Psychologist, 28(2), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034225

Kent, R. L., & Martinko, M. J. (2018). The development and evaluation of a scale to measure organizational attributional style. In M. J. Martinko (Ed.), Attribution theory (pp. 53–75). Routledge.

Kim, D., Lanaj, K., & Koopman, J. (2024). Incivility affects actors too: The complex effects of incivility on perpetrators work and home behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-024-05714-y

Kjærvik, S. L., & Bushman, B. J. (2021). The link between narcissism and aggression: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147(5), 477–503. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000323

Klasmeier, K. N., Schleu, J. E., Millhoff, C., Poethke, U., & Bormann, K. C. (2022). On the destructiveness of laissez-faire versus abusive supervision: A comparative, multilevel investigation of destructive forms of leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(3), 406–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2021.1968375

Krizan, Z., & Johar, O. (2015). Narcissistic rage revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(5), 784–801. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000013

Kruglanski, A. W., Ellenberg, M., Szumowska, E., Molinario, E., Speckhard, A., Leander, N. P., Pierro, A., Di Cicco, G., & Bushman, B. J. (2023). Frustration–aggression hypothesis reconsidered: The role of significance quest. Aggressive Behavior, 49(5), 445–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.22092

Lamer, S. A., Dvorak, P., Biddle, A. M., Pauker, K., & Weisbuch, M. (2022). The transmission of gender stereotypes through televised patterns of nonverbal bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 123(6), 1315–1335. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000390

Lannin, D. G., Guyll, M., Krizan, Z., Madon, S., & Cornish, M. (2014). When are grandiose and vulnerable narcissists least helpful? Personality and Individual Differences, 56, 127–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.08.035

Leith, K. P., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Empathy, shame, guilt, and narratives of interpersonal conflicts: Guilt-prone people are better at perspective taking. Journal of Personality, 66(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00001

Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. International Universities Press.

Liang, L. H., Coulombe, C., Brown, D. J., Lian, H., Hanig, S., Ferris, D. L., & Keeping, L. M. (2022). Can two wrongs make a right? The buffering effect of retaliation on subordinate well-being following abusive supervision. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000291

Mackey, J. D., Brees, J. R., McAllister, C. P., Zorn, M. L., Martinko, M. J., & Harvey, P. (2018). Victim and culprit? The effects of entitlement and felt accountability on perceptions of abusive supervision and perpetration of workplace bullying. Journal of Business Ethics, 153(3), 659–673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3348-7

Mackey, J. D., Frieder, R. E., Brees, J. R., & Martinko, M. J. (2017). Abusive supervision: A meta-analysis and empirical review. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1940–1965. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315573997

Mackey, J. D., McAllister, C. P., Ellen, B. P., III., & Carson, J. E. (2021a). A meta-analysis of interpersonal and organizational workplace deviance research. Journal of Management, 47(3), 597–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063198626

Mackey, J. D., Parker Ellen, B., McAllister, C. P., & Alexander, K. C. (2021b). The dark side of leadership: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of destructive leadership research. Journal of Business Research, 132, 705–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.037

MacKinnon, D. P., & Pirlott, A. G. (2015). Statistical approaches for enhancing causal interpretation of the M to Y relation in mediation analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314542878

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., Brees, J. R., & Mackey, J. (2013). A review of abusive supervision research. Journal of Organizational Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1888

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., & Dasborough, M. T. (2011). Attribution theory in the organizational sciences: A case of unrealized potential. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(1), 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.690

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., & Douglas, S. C. (2007). The role, function, and contribution of attribution theory to leadership: A review. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(6), 561–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.09.004