Abstract

Companies’ earnings are arguably their most important financial disclosure, and corporate tactics to manage earnings can be directly constrained by audit procedures. In this article, we examine whether there is a link between companies’ earnings performance and changes in the accounting firm they choose to audit their financial statements. We find that when companies’ reported earnings just miss analysts’ expectations, they are more likely to change their auditor. Consistent with an opportunistic auditor switch, we also find that these companies have lower levels of earnings quality after the change. Our results concentrate on companies with more incentive or ability to act opportunistically, including those with negative market reactions to earnings, higher levels of accruals flexibility, and weaker corporate governance. Our study advances research into the public’s interest by providing evidence of suspect auditor changes that increase auditors’ ethical conflict to maintain independence and objectivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Data are available from public sources identified in the text.

Notes

When examining metrics of financial performance, it is difficult to rule out an alternative explanation that auditor changes are driven by significant performance issues (DeFond & Subramanyam, 1998). In addition to controlling for company characteristics, we focus on companies near the earnings expectation benchmark to help us substantially reduce this concern.

Detailed statements are available at https://www.sec.gov/news/statement/munter-statement-assessing-materiality-030922.

Specifically, a U.S. Senate (1976) report documents the concern of possible opinion shopping of accountants. In the late 1980s, new amendments to the S-K, 8-K and 14-A disclosure requirements were made to address potential opinion shopping situations (SEC, 1988). Also, the SEC’s proposal of mandatory auditor rotation issued in August 2011 (PCAOB, 2011) was abandoned after receiving criticism that prescribed rules would increase auditor competition and stimulate clients’ opinion shopping behavior.

In a sample spanning from 1993 to 1996, only 26.3 percent of firms provided auditor–client realignment reasons aside from those required by mandatory disclosure rules. Hackenbrack & Hogan, (2002) document that 43.7 percent of their sample from 1991 to 1997 report reasons for auditor changes. Chang et al., (2010)’s sample spans from 2002 to 2006 and they find that only 22 percent of their observations disclose auditor change reasons, whether voluntarily or mandatorily.

Managers can walk down analysts’ forecasts by providing downward-biased earnings guidance (e.g., Burgstahler & Eames, 2006; Matsumoto, 2002), exclude some specific items from non-GAAP earnings (e.g., Doyle et al., 2013), or manipulate earnings through income shifting (Barua et al., 2010), real earnings activities (e.g., Burgstahler & Eames, 2006; Graham et al., 2005), or accounting accruals (e.g., Dhaliwal et al., 2004; Gupta et al., 2016; Payne & Robb, 2000) to meet or beat analysts’ forecasts.

Under Staff Accounting Bulletin (SAB) No. 99 issued by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), even a small quantitative misstatement could be qualitatively material to investors when it hides managements’ failure to meet analysts’ forecasts (SEC 1999).

Limited studies suggest auditors may not be fully incentivized to constrain earnings management behavior. Libby & Kinney, (2000) find that auditors are likely to make concessions on subjective matters. Brown-Liburd et al., (2013) provide evidence that auditors are insensitive to accounting decisions impacting market expectations.

Some companies that meet or far exceed earnings expectations may not perceive their auditor to be a constraint since they have met expectations and are less likely to employ accrual earnings management tactics because they do not require them. In addition, companies that miss expectations by a large margin may lack the ability to employ such tactics since the costs of earnings management increase as the missed amount increases (Burgstahler & Eames 2006). In our additional analyses we test a restricted sample of only just miss and just meet companies and find our results hold.

Although I/B/E/S does not cover all Compustat companies, it includes over 80 percent of the total assets and profits of the Compustat population (Davis et al., 2007) and is considered representative.

We use a GEE model because it allows us to account for various types of autocorrelation (Gardiner et al., 2009). The Huber sandwich style estimator of variance is used to account for heteroscedasticity. Taken together, the standard errors produced are HAC (heteroscedasticity-autocorrelation consistent).

As described in model (1), we measure all the control variables as of year t.

Standard errors are clustered by year.

Beginning with our full sample of 19,210 company-year observations from Table 1, our sample is reduced to 18,098 due to data availability to estimate the variables of model (2).

Control variable estimates are in line with our expectations. We observe a smaller magnitude of discretionary accruals (DA) for larger or older companies (SIZE and AGE), companies with higher book to market ratios (BTM), companies with higher institutional ownership (INT_OWN), and companies that record lower accruals in the past year (LAG_ACC). Companies with more sales growth (SALES_G), companies that report a loss (LOSS), and companies that are important to their auditor (IMP) report higher DA.

According to Benford’s Law, if a firm does not manipulate earnings, then the occurrences of the first digits of numbers (e.g., 1–9) of their financial statement line items should follow a certain distribution. FSD, simply put, captures the divergence of a firm’s financial statement from such expected distribution (Amiram et al., 2015).

We refrain from controlling for these variables in our main results as they significantly reduce sample size.

Our first stage determinant variables include return on assets, leverage, firm size, market-to-book ratio, the log audit fees, operating cash flows, Altman-z score, auditor tenure, institutional investor ownership, prior period meeting or beating earnings expectations, BigN auditor, the log of firm age, research and development expenses, positive seasonal change in earnings, the log of firms’ shares outstanding, labor intensity, the number of previous four quarters with negative earnings, the number of days between the fiscal year end and the earnings announcement, if the firm is in a litigation industry, macro-economic growth, and if the firm is included in the S&P 500 index (e.g., Filzen & Peterson, 2015; Huang et al., 2017).

References

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). 2020. AICPA Code of Professional Conduct. Durham, NC: AICPA (Updated through June 2020). Available at: https://us.aicpa.org/content/dam/aicpa/research/standards/codeofconduct/downloadabledocuments/2014-december-15-content-asof-2020-June-20-code-of-conduct.pdf

Amiram, D., Bozanic, Z., & Rouen, E. (2015). Financial statement errors: Evidence from the distributional properties of financial statement numbers. Review of Accounting Studies, 20(4), 1540–1593.

Ashbaugh, H. (2004). Ethical issues related to the provision of audit and non-audit services: Evidence from academic research. Journal of Business Ethics, 52(2), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000035912.06147.22

Asthana, S. C., & Boone, J. P. (2012). Abnormal audit fee and audit quality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 31(3), 1–22.

Archambeault, D., & DeZoort, F. T. (2001). Auditor opinion shopping and the audit committee: An analysis of suspicious auditor switches. International Journal of Auditing, 5(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/1099-1123.00324

Ayres, D. R., Neal, T. L., Reid, L. C., & Shipman, J. E. (2019). Auditing goodwill in the post-amortization era: Challenges for auditors. Contemporary Accounting Research, 36(1), 82–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12423

Barton, J., & Simko, P. J. (2002). The balance sheet as an earnings management constraint. The Accounting Review, 77(s-1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2002.77.s-1.1

Bartov, E., & Cohen, D. A. (2009). The “numbers game” in the pre-and post-Sarbanes-Oxley eras. Journal of Accounting Auditing & Finance, 24(4), 505–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X0902400401

Bartov, E., Givoly, D., & Hayn, C. (2002). The rewards to meeting or beating earnings expectations. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33(2), 173–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(02)00045-9

Barua, A., Lin, S., & Sbaraglia, A. M. (2010). Earnings management using discontinued operations. The Accounting Review, 85(5), 1485–1509. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2010.85.5.1485

Bhojraj, S., Hribar, P., Picconi, M., & McInnis, J. (2009). Making sense of cents: An examination of firms that marginally miss or beat analyst forecasts. Journal of Finance, 64(5), 2361–2388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2009.01503.x

Boone, J. P., Khurana, I. K., & Raman, K. K. (2012). Audit market concentration and auditor tolerance for earnings management. Contemporary Accounting Research, 29(4), 1171–1203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2011.01144.x

Brown, L. D., & Pinello, A. S. (2007). To what extent does the financial reporting process curb earnings surprise games? Journal of Accounting Research, 45(5), 947–981. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2007.00256.x

Brown-Liburd, H. L., Cohen, J., & Trompeter, G. (2013). Effects of earnings forecasts and heightened professional skepticism on the outcomes of client–auditor negotiation. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(2), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1473-5

Burgstahler, D., & Eames, M. (2006). Management of earnings and analyst’ forecasts to achieve zero and small positive earnings surprises. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 33(5–6), 633–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.2006.00630.x

Burks, J., & Stevens, J. (2021). Opaque auditor dismissal disclosures: What does timing reveal that disclosures do not? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2021.106905

Calderon, T. G., & Ofobike, E. (2008). Determinants of client-initiated and auditor-initiated auditor changes. Managerial Auditing Journal, 23(1), 4–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900810838146

Carcello, J. V., & Neal, T. L. (2000). Audit committee composition and auditor reporting. The Accounting Review, 75(4), 453–467. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2000.75.4.453

Carver, B. T., Hollingsworth, C. W., & Stanley, J. D. (2011). Recent auditor downgrade activity and changes in clients’ discretionary accruals. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 30(3), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-10053

Chang, H., Cheng, C. A., & Reichelt, K. J. (2010). Market reaction to auditor switching from Big 4 to third-tier small accounting firms. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 29(2), 83–114. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2010.29.2.83

Chen, F., Peng, S., Xue, S., Yang, Z., & Ye, F. (2016). Do audit clients successfully engage in opinion shopping? Partner-level evidence. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(1), 79–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12097

Cheng, Q., & Warfield, T. D. (2005). Equity incentives and earnings management. The Accounting Review, 80(2), 441–476. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2005.80.2.441

Chow, C. W., & Rice, S. J., (1982). Qualified audit opinions and auditor switching. The Accounting Review, 326–335.

Chung, H., Sonu, C. H., Zang, Y., & Choi, J. H. (2019). Opinion shopping to avoid a going concern audit opinion and subsequent audit quality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 38(2), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-52154

Coffee Jr., J (2019, January 24). Auditing Reform: Myth and Reality. Faculty of Law Blogs/University of Oxford. https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/business-law-blog/blog/2019/01/auditing-reform-myth-and-reality/

Davis, L. R., Soo, B. S., & Trompeter, G. M. (2007). Auditor tenure and the ability to meet or beat earnings forecasts. Contemporary Accounting Research, Forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1014601

Dechow, P., Ge, W., & Schrand, C. (2010). Understanding earnings quality: A review of the proxies, their determinants and their consequences. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2–3), 344–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.09.001

DeFond, M., & Zhang, J. (2014). A review of archival auditing research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58(2–3), 275–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2014.09.002

DeFond, M. L., & Subramanyam, K. R. (1998). Auditor changes and discretionary accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 25(1), 35–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(98)00018-4

DeFond, M. L., Hann, R. N., & Hu, X. (2005). Does the market value financial expertise on audit committees of boards of directors? Journal of Accounting Research, 43(2), 153–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679x.2005.00166.x

DeFond, M. L., Zhang, J., & Zhao, Y. (2018). Do managers successfully shop for compliant auditors? Evidence from accounting estimates. Evidence from Accounting Estimates (November 27, 2018). European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI)-Law Working Paper, (432).

Dhaliwal, D. S., Gleason, C. A., & Mills, L. F. (2004). Last-chance earnings management: Using the tax expense to meet analysts’ forecasts. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21(2), 431–459. https://doi.org/10.1506/TFVV-UYT1-NNYT-1YFH

Dhaliwal, D. S., Schatzberg, J. W., & Trombley, M. A. (1993). An analysis of the economic factors related to auditor-client disagreements preceding auditor changes. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 12(2), 22–38.

Dhole, S., Manchiraju, H., & Suk, I. (2016). CEO inside debt and earnings management. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 31(4), 515–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X15596907

Doyle, J. T., Jennings, J. N., & Soliman, M. T. (2013). Do managers define non-GAAP earnings to meet or beat analyst forecasts? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 56(1), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2013.03.002

Du, X., Xiao, L., & Du, Y. (2022). Does CEO–auditor dialect connectedness trigger audit opinion shopping? evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05126-w

Durtschi, C., & Easton, P. (2005). Earnings management? The shapes of the frequency distributions of earnings metrics are not evidence ipso facto. Journal of Accounting Research, 43(4), 557–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2005.00182.x

Eshleman, J. D., & Guo, P. (2014). Do Big 4 auditors provide higher audit quality after controlling for the endogenous choice of auditor? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 33(4), 197–219. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-50792

Filzen, J. J., & Peterson, K. (2015). Financial statement complexity and meeting analysts’ expectations. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32(4), 1560–1594. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12135

Frankel, R. M., Johnson, M. F., & Nelson, K. K. (2002). The relation between auditors’ fees for nonaudit services and earnings management. The Accounting Review, 77(s-1), 71–105. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2002.77.s-1.71

Gardiner, J. C., Luo, Z., & Roman, L. A. (2009). Fixed effects, random effects and GEE: What are the differences? Statistics in Medicine, 28(2), 221–239.

Gompers, P., Ishii, J., & Metrick, A. (2003). Corporate governance and equity prices. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 107–156. https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530360535162

Graham, J. R., Harvey, C. R., & Rajgopal, S. (2005). The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 40(1–3), 3–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2005.01.002

Gupta, S., Laux, R. C., & Lynch, D. P. (2016). Do firms use tax reserves to meet analysts’ forecasts? Evidence from the Pre-and Post-FIN 48 periods. Contemporary Accounting Research, 33(3), 1044–1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12180

Guo, J., Kinory, E., & Zhou, Y. (2021). Examining PCAOB disciplinary orders on small audit firms: Evidence from 2005 to 2018. International Journal of Auditing, 25(1), 103–116.

Habib, A., & Hossain, M. (2008). Do managers manage earnings to ‘just meet or beat’ analyst forecasts?: Evidence from Australia. Journal of International Accounting Auditing and Finance, 17(2), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2008.07.004

Hackenbrack, K. E., & Hogan, C. E. (2002). Market response to earnings surprises conditional on reasons for an auditor change. Contemporary Accounting Research, 19(2), 195–223. https://doi.org/10.1506/5XW7-9CY6-LLJY-BA2F

Haislip, J. Z., Myers, L. A., Scholz, S., & Seidel, T. A. (2017). The consequences of audit-related earnings revisions. Contemporary Accounting Research, 34(4), 1880–1914. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12346

Harris, D. G., Shi, L., & Xie, H. (2018). Does benchmark-beating detect earnings management? Evidence from accounting irregularities. Advances in Accounting, 41, 25–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2018.04.001

Hennes, K. M., Leone, A. J., & Miller, B. P. (2014). Determinants and market consequences of auditor dismissals after accounting restatements. The Accounting Review, 89(3), 1051–1082. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50680

Huang, S. X., Pereira, R., & Wang, C. (2017). Analyst coverage and the likelihood of meeting or beating analyst earnings forecasts. Contemporary Accounting Research, 34(2), 871–899. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12289

Jensen, M. C. (2005). Agency costs of overvalued equity. Financial Management, 34(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-053X.2005.tb00090.x

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

Jiang, J. (2008). Beating earnings benchmarks and the cost of debt. The Accounting Review, 83(2), 377–416. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2008.83.2.377

Jiang, J., Wang, I. Y., & Wang, K. P. (2019). Big N auditors and audit quality: New evidence from quasi-experiments. The Accounting Review, 94(1), 205–227. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52106

Jones, J. J. (1991). Earnings management during import relief investigations. Journal of Accounting Research, 29(2), 193–228. https://doi.org/10.2307/2491047

Karcher, J. N. (1996). Auditors’ ability to discern the presence of ethical problems. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(10), 1033–1050.

Ketz, J. E. (2020). The Myth of Auditor Independence. The CPA Journal, 90(2), 6–9.

Kim, Y., & Park, M. S. (2014). Real activities manipulation and auditors’ client-retention decisions. The Accounting Review, 89(1), 367–401. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50586

Kothari, S. P., Leone, A. J., & Wasley, C. E. (2005). Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(1), 163–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2004.11.002

Kouakou, D., Boiral, O., & Gendron, Y. (2013). ISO auditing and the construction of trust in auditor independence. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-03-2013-1264

Krishnan, J., (1994). Auditor switching and conservatism. The Accounting Review, 69(1), 200–215. http://www.jstor.org/stable/248267

Kwon, S. S., & Yin, Q. J. (2006). Executive compensation, investment opportunities, and earnings management: High-tech firms versus low-tech firms. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 21(2), 119–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X0602100203

Lawrence, A., Minutti-Meza, M., & Zhang, P. (2011). Can Big 4 versus non-Big 4 differences in audit-quality proxies be attributed to client characteristics? The Accounting Review, 86(1), 259–286. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.00000009

Lennox, C. (2000). Do companies successfully engage in opinion-shopping? Evidence from the UK. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 29(3), 321–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(00)00025-2

Libby, R., & Kinney, W. R., Jr. (2000). Does mandated audit communication reduce opportunistic corrections to manage earnings to forecasts? The Accounting Review, 75(4), 383–404. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2000.75.4.383

Lim, C. Y., & Tan, H. T. (2008). Non-audit service fees and audit quality: The impact of auditor specialization. Journal of Accounting Research, 46(1), 199–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2007.00266.x

Lin, Z. J., & Liu, M. (2010). The determinants of auditor switching from the perspective of corporate governance in China. Advances in Accounting, 26(1), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2010.03.001

Magee, R. P., & Tseng, M. C. (1990). Audit pricing and independence. The Accounting Review, 65(2), 315–336.

Mande, V., & Son, M. (2013). Do financial restatements lead to auditor changes? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 32(2), 119–145. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-50362

Matsumoto, D. A. (2002). Management’s incentives to avoid negative earnings surprises. The Accounting Review, 77(3), 483–514. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2002.77.3.483

Malsch, B., Tremblay, M. S., & Cohen, J. (2022). Non-audit engagements and the creation of public value: Consequences for the public interest. Journal of Business Ethics, 178(2), 467–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04777-5

Nekhili, M., Javed, F., & Nagati, H. (2022). Audit partner gender, leadership and ethics: The case of earnings management. Journal of Business Ethics, 177(2), 233–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04757-9

Newton, N. J., Persellin, J. S., Wang, D., & Wilkins, M. S. (2016). Internal control opinion shopping and audit market competition. The Accounting Review, 91(2), 603–623. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51149

Norris, F. (2006). Deep Secret: Why Auditors Are Replaced? The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/28/business/28norris.html

Payne, J. L., & Robb, S. W. (2000). Earnings management: The effect of ex ante earnings expectations. Journal of Accounting Auditing & Finance, 15(4), 371–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X0001500401

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB)., (2011). Concept Release on Auditor Independence and Audit Firm Rotation: Notice of Roundtable. Release No. 2011–006. Washington, DC: PCAOB. Available at: https://pcaobus.org/Rulemaking/Docket037/Release_2011-006.pdf

Reichelt, K. J., & Wang, D. (2010). National and office-specific measures of auditor industry expertise and effects on audit quality. Journal of Accounting Research, 48(3), 647–686. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2009.00363.x

Ronen, J., & Cherny, J. (2003). A prognosis for restructuring the market for audit services. The CPA Journal, 73(5), 6.

Sankaraguruswamy, S., & Whisenant, J. S. (2004). An empirical analysis of voluntarily supplied client-auditor realignment reasons. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 23(1), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2004.23.1.107

Schwartz, K. B., & Soo, B. S. (1996). The association between auditor changes and reporting lags. Contemporary Accounting Research, 13(1), 353–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.1996.tb00505.x

Shipman, J., Swanquist, Q., & Whited, R. (2017). Propensity score matching in accounting research. The Accounting Review, 92(1), 213–244. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51449

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)., (1988). Disclosure Amendments to Regulation SK, Form 8-K and Schedule 14A regarding changes in accountants and potential opinion shopping situations. Financial Reporting Release (31), 1140–1147. Washington, DC: GPO

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)., Materiality. Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 99. (August 12). Washington, DC: SEC, 1999.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)., (2004). Additional form 8‐K disclosure requirements and acceleration of filing date (final rule). Federal Register 69(58), 15594–15629. Washington, DC: GPO

Simunic, D. A., & Stein, M. T. (1990). Audit risk in a client portfolio context. Contemporary Accounting Research, 6(2), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.1990.tb00762.x

U.S. Senate., (1976). Accounting establishment: A staff study. Report of the Subcommittee on Reports, Accounting, and Management of the Committee on Government Operations. Available at: https://archive.org/stream/accstabl00unit/accstabl00unit_djvu.txt

Verwey, I. G., & Asare, S. K. (2022). The joint effect of ethical idealism and trait skepticism on auditors’ fraud detection. Journal of Business Ethics, 176(2), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04718-8

Watts, R. L., & Zimmerman, J. L. (1983). Agency problems, auditing, and the theory of the firm: Some evidence. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(3), 613–633.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: variable definitions

Appendix: variable definitions

Variables | Definition |

|---|---|

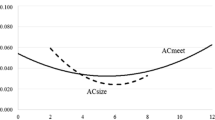

AC_SIZE | The number of audit committee members divided by the number of directors |

AC_IND | An indicator variable coded 1 if all audit committee members are independent, and 0 otherwise |

ACC | Net income less operating cash flows, net of cash flows for discontinued operations scaled by lagged total assets |

ACC_FLEX | The ratio of net operating assets to sales at the beginning of the year, scaled by industry-year median |

ACQ | Cash flows for acquisitions scaled by average total assets |

AGE | The natural log of firm age |

ALTMAN | Altman is calculated as:\(\begin{aligned} AltmanZ = & 3.3 \times \frac{{Net\, Income}}{{Total\, Assets}} + 0.99 \times \frac{{Sales}}{{Total\, Assets}} \\ & + 0.6 \times \frac{{Market\, Value}}{{Total\, Liabilities}} + 1.2 \times \frac{{Curent\, Assets}}{{Total\, Assets}} \\ & + 1.4 \times \frac{{Retained\, Earnings}}{{Total\, Assets}} \\ \end{aligned}\) |

AUD_CHG | An indicator variable coded 1 if the client changes its auditor within one year of the earnings announcement date, and 0 otherwise |

BD_IND | An indicator variable coded 1 if 60% or more of the directors are independent, and 0 otherwise (Consistent with DeFond et al., (2005)) |

BD_SIZE | The number of directors on the board |

BTM | The ratio of the book value to its market value of equity |

CASH | Cash and cash equivalents scaled by lagged total assets |

CAR | Accumulated market-adjusted stock returns for the (− 1, 1) window around the earnings announcement date |

CEOCFO_CHG | An indicator variable coded 1 if the company changed their CEO and/or CFO |

DA | The absolute value of performance-matched discretionary accruals. Discretionary accruals are estimated as the residuals from the Jones (1991) model and performance adjusted based on the return on assets (Kothari et al., (2005) |

DOWN | An indicator variable coded 1 if the client switches from a BigN auditor to a non-BigN auditor, and 0 otherwise |

FEE | The natural log of total audit fees |

FSD | Financial statement divergence is calculated as: \({\sum }_{1}^{9}(|AFi-EFi|)/9*100,\) where i = 1, 2, 3…9, and AF (EF) is the actual (expected) frequency of the first digit i from the financial statement items. If an item is smaller than one, then the next non-zero value after the decimal will be used as the first digit |

GC | An indicator variable coded 1 if the company received a going-concern opinion, and 0 otherwise |

GOV | Modified corporate governance index used in DeFond et al. (2005) |

HERF | Herfindahl index capturing the variation in the number of audit firms present in a given market, as well as the distribution of audit fees across those firms. The sum of the squared audit fee market shares of all auditors in an MSA |

IMP | The importance of the client to the auditor measured as the percentage of total audit fee revenue collected from the auditor’s client portfolio |

INV_AR | Inventory plus receivables divided by total assets |

ISSUE | The sum of debt or equity issued during the past three years scaled by total assets |

JUST_MISS | An indicator variable coded 1 if actual earnings per share minus consensus analysts’ forecasted earnings per share falls within the range of [− 0.01, 0], and 0 otherwise |

LAG_ACC | Total accruals in the prior year scaled by total assets |

LEVERAGE | Total short-term and long-term debt scaled by total assets |

LOSS | An indicator variable coded 1 if the company reported a loss, and 0 otherwise |

MEET_OR_BEAT | An indicator variable coded 1 if earnings per share minus consensus analysts’ forecasted earnings per is greater than or equal to zero, and 0 otherwise |

PSEUDO_MISS_FIRM | A pseudo just miss variable produced through random firm assignment using the quantity of just miss observations within the same industry-year |

PSEUDO_MISS_IND | A pseudo just miss variable produced through random year assignment using the quantity of just miss observations within the same firm |

RESTATE | An indicator variable coded 1 if the client announced a restatement during the prior-year to current-year earnings announcement date range, and 0 otherwise |

RESTRUCTURE | An indicator variable coded 1 if restructuring costs are present, and zero otherwise |

ROA | Net income before extraordinary items divided by total assets |

SALE_G | Percentage change in sales from the prior year |

SD_CASH | Volatility of cash flows calculated as the standard deviation of the operating cash flows in the last five years |

SIZE | The natural log of total assets |

TENURE | An indicator variable coded 1 if the current auditor has audited the company for more than five years, and 0 otherwise |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lohwasser, E., Zhou, Y. Earnings Management, Auditor Changes and Ethics: Evidence from Companies Missing Earnings Expectations. J Bus Ethics 191, 551–570 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05453-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05453-6