Abstract

This study investigates the likelihood of director turnover following opportunistic insider selling. Given that opportunistic insider selling may be costly to a firm due to potential legal risk and firm legitimacy concerns, we hypothesize that directors engaging in this type of transactions have a higher likelihood of subsequently leaving the board. Using archival data of 11,409 directors in 2280 US firms from 2005 to 2014, univariate comparisons show that directors engaging in opportunistic insider selling are about 8% more likely to exit their firms’ board compared to directors not engaging in this behavior. Furthermore, multivariate results show that the likelihood of director departure following opportunistic insider selling is higher for some directors but not all. Specifically, directors who are especially valuable to the board or costly to replace do not seem to experience elevated levels of turnover. Interestingly, this difference in director turnover is only observed in smaller firms. We find that in larger firms, the likelihood of director turnover following opportunistic insider selling does not depend on director characteristics. As such, results seem to suggest that boards do not homogeneously self-regulate in this context as some directors seem to be shielded from turnover following unethical behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Prior research provides consistent evidence that company insiders profit from buying and selling their company’s stock (e.g., Huddart & Ke, 2007; Lakonishok & Lee, 2001). Although insider trading can be considered useful in achieving market efficiency (Piotroski & Roulstone, 2005), opportunistic or informed insider trading is perceived by the public as inherently unfair (e.g., Billings & Cedergren, 2015) due to unequal treatment of different shareholders (Fassin, 2005). Insiders have a persistent capacity to realize abnormal profits when trading in their own companies’ shares due to their superior access to information (e.g., Billings & Cedergren, 2015; Gao et al., 2014; Jagolinzer et al., 2011). These information-rich trades are not to be confused with regular insider trades, which are generally uninformative about a firm’s future and usually driven by liquidity needs or portfolio rebalancing (Dai et al., 2016; Fidrmuc et al., 2006; Lakonishok & Lee, 2001).

Regulators try to limit opportunistic insider trading by imposing various restrictions on insider tradingFootnote 1 and many firms implement ex-ante voluntary insider trading policies, such as defining blackout periods or requiring approval from the general council. In addition, in accordance with section 16 of the Securities and Exchange act of 1934, all insidersFootnote 2 must publicly disclose changes in their ownership following a transaction.Footnote 3 This public disclosure is instrumental in informing the public of trades by insiders and in identifying unusual trading patterns, which might signal information-based trading.

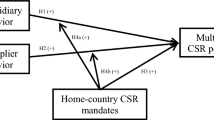

In this study, we focus on firm actions following director opportunistic insider selling and investigate whether directors engaging in this type of unethical behavior experience a higher likelihood of subsequent board turnover.Footnote 4 Moreover, we assess whether the likelihood of director turnover following unethical behavior is equal for all directors or varies with their replaceability within the board and firm visibility. As such, we not only attempt to shed light on boards’ tendencies to self-regulate director unethical behavior but also on the trade-off between retention and replacement costs of directors engaging in unethical behavior. Specifically, we investigate whether certain types of directors (i.e., those that are costly to replace or have high value to the board) are potentially shielded from turnover following opportunistic insider selling and whether differences in director turnover following unethical behavior vary with firm size.

We argue that there are at least two reasons why firms may want to avoid director opportunistic insider selling. First, insiders exploiting negative private information may expose the firm to legal risk (Dai et al., 2016). Given that opportunistic insider selling (i.e. outside the insider’s usual pattern of trades) significantly increases the likelihood of subsequent SEC enforcement actions (e.g. Billings & Cedergren, 2015; Cohen et al., 2012), firms likely want to restrict director opportunistic selling in order to minimize legal exposure. Second, given that opportunistic trading is generally perceived as unfair and unethical (Abdolmohammadi & Sultan, 2002; Johnson et al., 2018; McGee, 2010) retaining a director engaging in this behavior might be costly because it not only exposes the firm to legal risk but also potentially threatens board perceived legitimacy. According to institutional theory, directors serve not only to advise and monitor management but also to provide symbolic legitimacy to the firm (Kachelmeier et al., 2016). When directors engage in (publicly visible) unethical behavior, the cost of retaining them increases as firms wish to preserve their public legitimacy (Harris, 2007; Sullivan et al., 2007). Extending the CEO retention framework developed in Beneish et al. (2017) to all directors on the board, we expect that firms try to distance themselves from directors engaging in opportunistic insider selling, resulting in an increased likelihood of turnover (Suchman, 1995).Footnote 5 However, director turnover following unethical behavior is likely also influenced by director replacement costs and the severity of potential firm legitimacy damage. Therefore, we expect the association between turnover and opportunistic selling to vary with (i) a director’s position in the firm and (ii) firm size.

We use archival data of 11,409 directors in 2280 US firms from 2005 until 2014 and adopt the widely used Cohen et al. (2012) methodology to identify “opportunistic” insider sales (Billings & Cedergren, 2015; Khan & Lu, 2013; Michaely et al., 2016) by focusing on unusual patterns in director trading behavior. Specifically, we consider sales for a particular insider to be routine transactions if they are placed in the same calendar month for at least 3 consecutive years (Cohen et al., 2012). Other sales transactions, which are unusual given an insider’s trading pattern over the last 3 years, are classified as opportunistic sales. Using this methodology to classify insider sales transactions, we find that director opportunistic insider selling is positively associated with their likelihood of turnover. However, the association between opportunistic insider selling and director turnover is not equal across directors and firms. We find evidence that executive directors, directors in key board positions (i.e., board chairperson or chairperson of the compensation, nomination, or audit committee), and directors who are in high demand (e.g., financial experts) are not subject to a higher likelihood of turnover following opportunistic insider selling. This is, however, only true for board members of small firms. We find that in larger (and hence more visible) firms, unethical director behavior is more likely to be associated with subsequent turnover, regardless of director value to the board or firm. Additional analyses furthermore show that director turnover following opportunistic insider selling is concentrated in directors without ties to the CEO as well as younger and shorter tenured directors. The latter result seems to suggest that our findings may be indicative of unexpected director turnover (Fahlenbrach et al., 2017). Other additional tests using alternative measures for director turnover as well as for opportunistic insider selling, confirm the robustness of the results found. Finally, overall results hold using entropy balancing and alternative fixed effect model specifications.

We contribute to existing research in various ways. First, this study extends the literature on the consequences of director unethical behavior by showing that that opportunistic selling by individual directors is associated with an increased turnover rate for some directors, but not all. As such the results potentially suggest that some firms reject unethical behavior and tend to self-regulate their boards, but their decision to do so depends on the cost associated with director replacement. By showing that directors in small (less visible) firms only face a higher likelihood of turnover when they do not occupy a key position in the board or firm, we provide evidence that ethical considerations, though important to the firm, do not always outweigh other firm considerations. Our results seem to suggest that replacement of directors engaging in opportunistic insider selling is the result of a careful cost–benefit analysis, taking into account director value to the firm as well as firm visibility. Second, to the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to investigate the relationship between individual director behavior and the likelihood of subsequent director turnover. Previous studies on director turnover mainly focused on firm-level events such as restatements or fraud (e.g. Agrawal et al., 1999; Arthaud-Day et al., 2006; Brochet & Srinivasan, 2014; Fich & Shivdasani, 2007; Marcel & Cowen, 2014; Srinivasan, 2005). Our study adds to this literature by focusing on the association between director opportunistic selling and subsequent turnover. As such, we do not only provide further evidence of an association between individual director wrongdoing and subsequent turnover but also introduce a new measure of unethical behavior in the director turnover literature. Third, this study also extends the literature on insider trading, which to date has focused on effects at the financial market or firm level, such as increased likelihood of firm litigation (e.g., Billings & Cedergren, 2015) or increased cost of capital (e.g., Bhattacharya & Daouk, 2002). In contrast, we relate insider selling behavior to individual director labor market consequences and show a positive association between opportunistic insider selling behavior and the likelihood of subsequent director turnover for some directors.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. First, we provide an overview of the relevant literature and develop this study’s main hypotheses. Next, we present the research design and sample selection, followed by the results and additional analyses. Finally, we provide a summary of the main findings and concluding remarks.

Relevant Literature and Hypothesis Development

Opportunistic insider selling can be considered as unethical under both rights-based and utilitarian views. Under the rights-based view, insider trading behavior is considered undesirable if the transaction violates someone’s rights. As opportunistic sales are often based on information obtained through the insider’s position in the firm, which is an information channel outsiders cannot access through their own independent and lawful due diligence, we argue that this behavior is considered unethical as well as unfair from the rights-based angle (Klaw & Mayer, 2019; McGee, 2008). In this case, the rights of other shareholders are violated because they have no legal access to the information on which the insider trading activity is done (Chang & Lim, 2016). From a utilitarian point of view, an action is viewed as good if the result is the greatest good for the greatest number (Mill, 1861/1879). Although some scholars have argued that through their trading behavior, insiders release private information to the market which increases market efficiency (Ma & Sun, 1998; Manne, 2005; McGee, 2008), insider selling comes with significant costs, e.g. a higher cost of capital (e.g., Aboody et al., 2005; Bhattacharya & Daouk, 2002), lower market liquidity (Bhattacharya & Daouk, 2002; Fishe & Robe, 2004), lower earnings quality (Huang et al., 2020), and increased litigation risk (Billings & Cedergren, 2015; Johnson et al., 2007; Jones & Weingram, 1996). Although opportunistic insider selling might benefit the individuals engaging in this behavior, it also entails significant societal costs given that these trades are based on proprietary information. This unfairness may cause investors to lose confidence in the capital market because it is viewed as an unequal playing field. Therefore, the process of capital formation and allocation may deteriorate which in the long run has negative consequences for the economy. In other words, opportunistic insider trading is likely not considered ethical under the utilitarian view because it does not create the greatest value for the greatest number of people, i.e. it only benefits insiders and not the other shareholders nor the firm itself.

Overall, we believe that due to having private information insiders can profit from opportunistic insider selling while other shareholders as well as firms suffer losses. To avoid negative consequences, firms generally ex-ante restrict insider trading by specifying blackout periods or requiring approval from the general council (Bettis et al., 2000; Dai et al., 2016; Jagolinzer et al., 2011). Alternatively, they can take ex-post actions against opportunistic insiders by removing them from the board. Our focus is on the latter, as we investigate the likelihood of director turnover following opportunistic insider selling.

Current literature on director turnover following unethical behavior mainly focuses on firm-level events such as restatements (Arthaud-Day et al., 2006; Srinivasan, 2005), fraud (Agrawal et al., 1999; Brochet & Srinivasan, 2014; Fich & Shivdasani, 2007; Marcel & Cowen, 2014), derivative lawsuits (Ferris et al., 2007) or stock option backdating (Ertimur et al., 2012). Table 1 provides an overview of studies conducted in this area of research. Although these studies provide preliminary evidence of disciplinary turnover following firm-level unethical behavior, few studies link individual director behavior to their likelihood of turnover. One notable exception is Brochet and Srinivasan (2014), investigating whether directors named as defendants in a firm fraud lawsuit were more likely to leave the board, as opposed to directors not named in the lawsuit. Our study extends this line of research by focusing on director turnover following opportunistic insider selling. As such, we make a distinct contribution to the literature by linking individual director unethical behavior to their likelihood of turnover from the board. In addition, we examine whether the decision to replace an unethical director is influenced by the replaceability of this director as well as the specific context of the firm. Although prior director turnover studies have distinguished between certain types of directors to assess which directors are being held accountable for firm-level unethical behavior (e.g. Arthaud-Day et al., 2006; Ertimur et al., 2012), we are the first to focus on individual director wrongdoing and to use various director characteristics to examine how director retention and replacement costs influence their likelihood of turnover. Specifically, we investigate whether directors who are especially valuable (due to specific expertise or the occupation of a key role in the board of firm) face a lower likelihood of turnover when they engage in opportunistic insider trading. We also argue that unethical director retention and replacement costs likely differ between small and large firms and show that the association between director opportunistic selling and subsequent turnover is influenced by company size. As such, we extend prior work by showing that firms tend to self-regulate unethical behavior. However, they do not apply a uniform ethical standard to all board members, as we only find self-regulation when the benefits of doing so outweigh the costs.

To explain director turnover following opportunistic insider selling, we first focus on legal risk due to director opportunistic insider selling. As all insiders must publicly disclose their trading behavior within 2 days through SEC Form 4, trades which may be perceived as opportunistic potentially expose a firm to legal investigations. Billings and Cedergren (2015) and Cohen et al. (2012) indeed show that opportunistic sales transactions (i.e. sales outside the insider’s usual pattern of trades) significantly increase the likelihood of subsequent SEC enforcement actions. This is consistent with the SEC’s use of data analysis tools to detect suspicious trading patterns. Focusing on legal risk as an incentive for firms to limit opportunistic insider selling, Dai et al. (2016) show that well-governed firms especially tend to restrict the profitability and opportunistic timing of sales transactions that do not fit in the insider’s usual trading pattern, given that these transactions are more likely to attract legal problems.

We draw on institutional theory to argue that firms likely want to avoid opportunistic selling and the associated risk of SEC investigation as the latter may bring about legal costs but also might damage firm legitimacy. According to institutional theory, firms seek legitimacy within social and cultural systems by adhering to the “system of norms, values, beliefs” of the institutional environment in which they operate (Suchman, 1995, p. 557). Given that the public associates insider selling behavior with greed, unfairness, and insider exploitation of uninformed stakeholders (Cui et al., 2015; Gao et al., 2014; Klaw & Mayer, 2019; Salbu, 1995), we argue that public disclosure of SEC investigation of director opportunistic selling may pose a significant threat to the public perception of firm legitimacy. Even without a formal SEC investigation, opportunistic sales transactions reported through SEC Form 4 are likely to be perceived as unfair and unethical (Abdolmohammadi & Sultan, 2002; Johnson et al., 2018). From a rights-based perspective, information-rich insider sales violate the rights of other shareholders who do not have legal access to the information on which the insider selling activity is done. They benefit only the insiders engaging in those sales whereas other, less informed investors, suffer losses. As such, this behavior may be perceived as “just not right” (McGee, 2010). Consequently, if investors become aware of director opportunistic selling, partner firms, individuals and other significant stakeholders likely might avoid being linked with them, which could have significant financial consequences and negatively impact firm performance (Sullivan et al., 2007). We expect firms to reduce the risk of potential legitimacy damage by distancing themselves from unethical directors engaging in opportunistic insider selling (Arthaud-Day et al., 2006; Suchman, 1995), for example by not renewing their board mandate. As such, the firm not only prevents potential legal action but also signals that it values proper conduct and does not tolerate counter-normative behavior among its directors (Cowen & Marcel, 2011).Footnote 6 This expectation results in the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Directors’ opportunistic insider selling is positively associated with the likelihood of turnover from their firms’ board.

Removing a potentially unethical director can be beneficial in terms of addressing legal risk and firm legitimacy concerns. However, the cost of retaining an opportunistic director is only one factor involved in this decision, the cost of replacing the director being the other (Beneish et al., 2017). Outside directors are invited to be members of the board because they bring important resources to the firm, such as access to external parties or human capital (i.e., experience and expertise) or because they oversee corporate governance issues. Prior studies (e.g., Chidambaran et al., 2015; Renneboog & Zhao, 2020; Yermack, 2004) indeed show that key outside board members, such as committee members, committee chairs, and lead directors, are less likely to be replaced compared to directors without a key position due to higher replacement costs.Footnote 7 Since the enactment of the Sarbanes Oxley Act, financial experts also have been in high demand on boards (Alam et al., 2018; Erkens & Bonner, 2013; Linck et al., 2009). They are difficult to replace due to local director supply constraints (Alam et al., 2018), which further increases the value of financial experts. Likewise, the company’s inside directors, which typically include the company’s top executives, such as the CEO, CFO and COO are more costly to replace as they fulfill key positions in the firm. Therefore, we argue that the cost to replace these valuable directors might result in a weaker association between their opportunistic insider selling and subsequent likelihood of turnover.

Summarizing this line of reasoning, our second hypothesis considers the moderating role of director value in the relationship between director opportunistic insider selling and subsequent turnover. We expect directors with key positions on the board, either due to their specific expertise, board role or function within a firm, to be shielded from turnover following opportunistic insider selling:

Hypothesis 2

The association between opportunistic insider selling and the likelihood of director turnover is less pronounced for valuable directors compared to less valuable directors.

The cost of retaining a director involved in opportunistic selling compared to the cost of replacement is likely not only influenced by director but also by firm characteristics such as firm size. First, the deep pocket theory predicts that larger firms experience higher legal risk and have more at stake in case of litigation (Adams & Ferreira, 2008; Fama & Jensen, 1983; Kim & Skinner, 2012). Furthermore, the costs of director counter-normative behavior to the firm tend to increase with the visibility of this behavior. Although director trades are disclosed through SEC Form 4 and hence publicly available, outside investors do not always pay attention to these (less visible) disclosures (Rogers et al., 2016). Subsequent coverage of insider trading news increases in intensity with company size (Dai et al., 2015), making director insider selling behavior especially cumbersome for large companies. These insider trades not only increase potential legal risk (Agrawal & Cooper, 2015; Badertscher et al., 2011; Beneish et al., 2012; Dai et al., 2015) but may also be damaging to board legitimacy. As a result, we expect valuable directors in large firms to face an equally high likelihood of turnover following opportunistic selling than their non-valuable counterparts, given the high ex-ante litigation risk of these firms (Kim & Skinner, 2012).

Second, the cost of director replacement is likely to be smaller for large firms as they potentially have a larger pool of director candidates compared to small firms. Directorships at large firms are especially attractive because they not only provide directors with status, visibility, prestige (Adams & Ferreira, 2008; Shivdasani, 1993) and higher compensation (Ryan & Wiggins, 2004), but also a higher likelihood of obtaining additional directorships (Fich, 2005; Yermack, 2004). The attractiveness of board seats in large firms might influence the available director candidate pool for these firms as directors—given their time constraints—are likely to prioritize which boards to serve on (Masulis & Mobbs, 2014). This, in turn, might translate into a lower replacement cost of directors engaging in unethical behavior at large firms. Based on these arguments, we expect that in large firms opportunistic trading will be more strongly associated with director turnover, regardless of director value to the board:

Hypothesis 3

The difference in turnover following opportunistic insider selling between valuable and less valuable directors is less pronounced in large firms compared to small firms.

Data and Research Design

Data and Sample

To investigate the different hypotheses, we need director trading data as well as data regarding individual director as firm data. To create our insider selling dataset, we rely on the Thompson Reuters Insiders Data Feed from Form 4 filings. This dataset includes insider sales data on directors, officers, and large stockholders with holdings greater than 10% of a firm’s stock, for firms listed on NYSE, AMEX, or NASDAQ. Given the research setting, we focus on sales transactions actively placed by board members and exclude sales resulting from the exercise of options.

Although the initial period spans from January 2002 to March 2014, the usable range is limited to insider sales from January 2005 onwards as the methodology of Cohen et al. (2012) used to identify opportunistic insider selling behavior requires a preceding 3-year window (Cohen et al., 2012). We match this sample containing transactions by insiders to individual director characteristics and board-level information from BoardEx, firm-level financial information from Compustat and Audit Analytics, and stock performance indicators from CRSP. The initial sample comprises 53,344 director-firm years that appear in all five databases. After excluding 3747 observations with missing values, the final sample comprises 49,597 unique director-firm years, with data from 11,409 directors and 2280 individual firms.

Model

To study the impact of opportunistic insider selling on director turnover we estimate a linear probability model (LPM) wherein the likelihood of turnover for director i in firm j for fiscal year t (TURNOVERi,j,t) is the dependent variable.Footnote 8TURNOVERi,j,t is measured as a dichotomous variable, which is equal to one if director i leaves the board of firm j within 3 years starting year t, and zero otherwise. In line with previous literature (Srinivasan, 2005) we employ a 3-year window to measure director turnover as it ensures that all directors face reelection at least once over the course of the measurement window.Footnote 9 The model is specified as follows:

Variables predicted to have an influence on director turnover are classified in two different groups: (1) the variables of interest i.e. opportunistic selling behavior (OPP SALEi,j,t), director value (VALUABLEi,j,t), and firm size (LARGEj,t), (2) other director and firm characteristics. All models include year and firm fixed effects with standard errors corrected for clustering at the firm level.Footnote 10

Test Variables

To test hypothesis 1, we distinguish between regular or routine insider sales on the one hand and opportunistic insider sales on the other hand. As the opportunistic nature of a director trade is not disclosed, we use the widely adopted methodology of Cohen et al. (2012) to classify insider sales transactions as “opportunistic” or “routine” (e.g. Billings & Cedergren, 2015; Dai et al., 2016; Khan & Lu, 2013; Michaely et al., 2016). To identify insider sales which are most likely based on private information, we compare each insider sale transaction to transactions of the same insider in the same company in the last 3 years. Insider sales which are placed in a calendar month in which the insider has placed transactions for at least the past 3 consecutive years are labeled as routine sales (Cohen et al., 2012). Insider sales placed by an insider trading for 3 consecutive years but whose trades do not follow such a pattern are more likely to be information-based and hence classified as opportunistic. This classification method requires 3 years of past insider trading history, sales of insiders not fulfilling this requirement are labeled as not classifiable. It should be noted that an insider may engage in both routine and opportunistic trades during the same calendar year. We apply this procedure to all open market purchases and sales reported by insiders to EDGAR, through their form 4 filings. As such we can allocate a status of “routine”, “opportunistic”, or “not-classified” to each open market transaction.Footnote 11 A practical example illustrating the Cohen et al. (2012) classification method can be found in the Appendix.

Using the Cohen et al. (2012) measure to classify insider sales, we define the variable OPP SALEi,j,t as the ratio of total share volume sold opportunistically to total share volume sold by director i at firm j for fiscal year t.Footnote 12 We focus exclusively on insider sales because purchases generally convey positive information about the firm’s future (Lakonishok & Lee, 2001), are less likely result in SEC investigation and litigationFootnote 13 (e.g., Billings & Cedergren, 2015; Brochet & Srinivasan, 2014; Cheng & Lo, 2006; Dai et al., 2015, 2016) and hence are also less likely to pose a threat to firm legitimacy.

To test hypothesis 2, we use the variable VALUABLEi,j,t to capture the value of a director to its firm. VALUABLEi,j,t is a dichotomous variable equal to one if a director fulfils an executive role in the firm (EXECUTIVEi,j,t), and/or has a key position in the board (KEY DIRECTORi,j,t), and/or has accounting expertise (ACFEi,j,t). We define key director positions as the chairperson of the board, the lead director, or the chairperson of the audit, compensation, or nomination committee (Chidambaran et al., 2015; Yermack, 2004). Director accounting expertise is determined using a director’s biographic information in the BoardEx database. Directors are considered accounting financial experts if their biographic information in the BoardEx database includes terms reflecting accounting or auditing expertise, such as certified public accountant, auditor, controller, treasurer, accountant, or chief financial officer (e.g., Erkens & Bonner, 2013; Cohen et al., 2014; Duellman et al., 2018) or if their biographic information indicates that they are or have been employed at one of the 25 current and historical audit firms listed in Compustat (Badolato et al., 2014). We combine all three determinants of director value into one dichotomous variable (i.e. VALUABLEi,j,t), but also conduct analyses in which we test each determinant separately.

To test hypothesis 3, we differentiate between larger and smaller firms by using a dummy variable LARGEj,t, based on the market value of equity at the start of the TURNOVERi,j,t window. We define firms as large when their market value at the beginning of the fiscal year places them in the top half of all companies within their industry and year in our sample.Footnote 14Footnote 15

Director and Firm Characteristics

Based on previous literature, we add director characteristics, governance measures and firm characteristics as control variables in out model (Farrell & Whidbee, 2003; Ferris et al., 2003; Fich & Shivdasani, 2007; Gilson, 1990; Hermalin & Weisbach, 1998; Karpoff et al., 2008; Srinivasan, 2005; Westphal & Zajac, 1995; Yermack, 2004). Specifically, we control for director committee membership (COMMITTEE MEMBERi,j,t), the years until a director reaches the age of retirement (TIME TO RETi,j,t), director tenure (BOARD TENUREi,j,t) and the number of external board positions (BOARD POSITIONSi,j,t).

In terms of firm overall governance quality, we control for CEO power (POWER CEOj,t), reflecting whether the CEO is either the founder of the company or the chair of the board, or both; the presence of a new CEO (CEO REPLACEMENTj,t), board size (BOARD SIZEj,t), board independence (%INDEPENDENTj,t), board busyness (%BUSYj,t), and the overall opportunistic selling behavior of the board (BOARD OPPORTUNISMj,t). The latter variable measures how common opportunistic insider selling is on the board. We also control for firm reputation by including the variable HIGH REPUTATIONj,t, which identifies whether a company is included in Fortune magazine's list of America's Most Admired Companies in a certain fiscal year (Erkens & Bonner, 2013; Cao et al., 2015).

Finally, in all regression models we include the natural logarithm of the market value of equityFootnote 16 at the beginning of the fiscal year (FIRM SIZEj,t), the announcement of a restatement during the fiscal year (RESTATEMENTj,t); and the performance of the firm (PERFORMANCE,j,t), which is the difference between the CRSP value-weighted index return and the firm’s stock return, both measured over the same time as TURNOVERi,j,t. We also include the average ROAj,t, and Tobins Qj,t measured over the same time window as TURNOVERi,j,t for comparability to previous literature. An overview of variable definitions can be found in Table 2.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 describes the summary statistics for all variables. Continuous variables are winsorized at top and bottom 1% levels. Panel A provides information on director turnover rate. In line with previous research (Asthana & Balsam, 2010; Yermack, 2004), 20.8% of all directors are replaced from the board within 3 years, suggesting an expected board tenure of about 14 years. Turnover remains stable over our sample ranging from 19.6% in 2009 to 23.1% in 2012. When comparing directors who sell shares opportunistically to those that do not, we find that opportunistic sellers have a 1.5% higher likelihood of turnover (p-value = 0.000). In other words, compared to directors who do not sell shares opportunistically, directors who sell shares opportunistically are about 1.08 times as likely to leave the board in the next 3 years.

Panel B of Table 3 provides descriptive information of OPP SALEi,j,t. and shows that insiders on average sell about 35.0% of shares opportunistically.Footnote 17 However, the distribution is highly skewed as for more than half of the observations no opportunistic selling is observed. The sample mean (median) number of shares traded is 185,970 (7297), of which on average of 94,967 shares are sold opportunistically. Directors who engage in at least one opportunistic sale during the year sell and average of 213,097 shares over that whole year, for a total value of $4,074,052, indicating that those directors sell higher volumes than average. In addition, untabulated results show that valuable directors engage in more insider selling transactions (6.72 vs. 2.86, p-value = 0.000) and sell higher share volumes (119,345.37 vs. 39,005.94, p-value = 0.000) compared to less valuable directors. A comparison of the selling behavior of executive, key and ACFE directors reveals that the high opportunistic selling activity by valuable insiders is mainly due to executive insider selling activity (59.07% of shares sold in opportunistic sales), and not to insider sales executed by key directors (28.65% of shares sold in opportunistic sales) or ACFEs (25.53% of shares sold in opportunistic sales). This finding is in line with Cline et al. (2017) and can be explained by executives often possessing privileged information regarding their companies.

Panel C details the director level variables used and shows that 65.8% directors meet at least one of the criteria to be considered valuable. In the breakdown between valuable and less valuable directors, untabulated results show that the director turnover rate is 7.35% lower for the former group (p-value = 0.000). When focusing on individual drivers of director value, we note that 45.0% of directors in our sample occupy a key position in the board (i.e., lead directors, chairpersons of the board, or chairperson of key committees), whereas 26.8% possesses accounting financial expertise and 22.7% are executive directors. Finally, we find that the average board tenure is approximately 11.25 years, and the average director is 6 years from retirement. The average number of board positions held was 1.66, and 65.3% fulfilled roles on at least one board committee.

Panel D details the firm-level variables used. In our sample, 62.3% of observations are classified as large firms, i.e. ranked above the median of market value of equity for their industry-year. As expected, the rate of director turnover is significantly higher in these larger firms (p-value = 0.000). Surprisingly, insiders in larger firms tend to sell a larger proportion of shares opportunistically compared to their counterparts in smaller firms (p-value = 0.000). Turning our attention to firm-level control variables, we find that boards in our sample are large (9.77 board members on average), consist mainly of independent directorsFootnote 18 (78.3%, on average) along with busy directors (7.3%). Furthermore, 52.7% of sample firms have a “high power” CEO while for 26.0% of director-firm-years the CEO has just been replaced. Although opportunistic selling is common in our sample, on average only 7.9% of share volume traded by board members was opportunistically sold. Finally, on average, sample firms had a market value of equity of 5.388 billion US$, an average ROA of 6.5% over 3 years, an average Tobin’s Q of 1.659 over 3 years, and they outperformed the market by 10.5% over 3 years.

To further illustrate the damages done by opportunistic selling, we provide some descriptive statistics regarding trade profitability in Table 4 for a subsample of 64,747 insider sales transactions for which we are able to obtain information regarding abnormal returns.Footnote 19 If opportunistic sales transaction result in similar profits as routine sales, this might indicate that no inside information is used. If, on the other hand, opportunistic sales transactions are more profitable compared to routine transactions, it is likely that insider information is used, which suggests unethical behavior by insiders (e.g. Abdolmohammadi & Sultan, 2002). Following prior literature (Dai et al., 2015, 2016; Hillier et al., 2015; Ravina & Sapienza, 2010), we compute the cumulative abnormal stock return (CAR) over the 180 trading days starting from the transaction date.Footnote 20 Univariate results show that opportunistic insider sales have a CAR that is ten times higher than routine sales (10.80% vs. 1.07%, p-value = 0.000) and that these transactions are also more likely to be profitableFootnote 21 (58.85% vs. 45.44%, p-value = 0.000). We find that opportunistic sales transactions generate on average $17,993.91 more in dollar profit (p-value = 0.082), although opportunistic sales transactions are larger in share volume (37,529.39 vs. 9421.93; p-value = 0.000) and trade value ($1,038,907.00 vs. $271,213.21; p-value = 0.000), compared to routine sales transactions. Taken together, this shows that opportunistic sales are significantly more profitable compared to routine sales, indicating that they are more likely to be information-based. From both a utilitarian and rights-based view this would indicate that opportunistic insider sales can be considered unethical. Insiders are extracting profits from the market, causing losses for uniformed investors. In addition, they are likely doing so using inside information to which outside investors have no access.

Table 5 summarizes correlations between all variables in our regression models. Correlation coefficients presented in bold are statistically significant at the 5% level. As expected, opportunistically selling shares (OPP SALEi,j,t) correlates positively with the likelihood of being replaced (TURNOVERi,j,t). Correlations between most control variables are limited, with the exception of VALUABLEi,j,t, and KEY DIRECTORi,j,t (corr = 0.6521) and EXECUTIVEi,j,t and COMMITTEE MEMBERi,j,t (corr = − 0.7265). Note however that VALUABLEi,j,t, and KEY DIRECTORi,j,t never appear in the same model together, and variance inflation factors indicate no issues with multicollinearity between EXECUTIVEi,j,t and COMMITTEE MEMBERi,j,t.Footnote 22 However, some variables are associated with higher variance inflation factors, such as BOARD SIZEj,t and %INDEPENDENTj,t.Footnote 23 Therefore, we standardize both variables and report coefficients for these standardized regressors in all tables. This procedure reduces our maximal variance inflation factor to 4.53 for COMMITTEE MEMBERi,j,t. Inferences are identical for models using standardized and non-standardized variables.Footnote 24

Multivariate Results

The multivariate results testing the different hypotheses are shown in Tables 6, 7, and 8. In all models, we introduce year as well as firm fixed effects to control for time-series as well as cross-sectional variation between observations. Although adding firm fixed effects makes it more difficult to find statistically significant relationships between dependent and independent variables (Zhou, 2001), it mitigates the influence of unobservable time-invariant firm characteristics which could influence the association between opportunistic insider selling and director turnover (e.g. firm culture or the ownership structure of the firm).

In line with our first hypothesis, results in Table 6 show that opportunistic director selling, which is generally perceived as unethical by the public, is positively associated with the likelihood of director turnover. In terms of economic significance,Footnote 25 a one standard deviation increase in opportunistic sales is associated with an increase in turnover equal to 4.83% of the average likelihood of turnover. Consistent with expectations, we find that valuable directors have a significantly lower likelihood of turnover, with valuable directors being 7.09% less likely to lose their board position than less valuable directors. Results are similar when testing the individual determinants of director value, showing that executives, key directors, and accounting experts are all significantly less likely to be replaced. In addition, directors at large firms also face a significantly lower likelihood of replacement. Furthermore, consistent with previous research (Arthaud-Day et al., 2006; Asthana & Balsam, 2010; Cowen & Marcel, 2011; Marcel & Cowen, 2014; Srinivasan, 2005; Yermack, 2004) directors who are further away from retirement, sit on a board committee, or have more external board positions are less likely to be replaced whereas higher tenured directors face a higher likelihood of turnover.

Finally, results related to firm-level control variables indicate that increased stock market as well as accounting performance are associated with a lower likelihood of director turnover, whereas CEO power, board size, and overall board opportunism are significantly associated with a higher likelihood of director turnover.

To test our second hypothesis, we estimate the association between opportunistic insider selling and the likelihood of director turnover, conditional upon the director being valuable to the board. This conditional estimation strategy results in two coefficient estimates for the effect of OPP SALEi,j,t on director turnover. The coefficient of OPP SALEi,j,t when VALUABLEi,j,t = 0 captures the association between opportunistic insider selling and director turnover for directors who do not have accounting financial expertise, do not fulfil a key position, nor are members of the company’s top management. The coefficient of OPP SALEi,j,t when VALUABLEi,j,t = 1 captures the association between opportunistic insider selling and director turnover for directors with high value to the board. This approach is equivalent to a traditional interaction analysis.Footnote 26 However, it allows for a direct comparison of the association between opportunistic insider selling and director turnover for directors that are more versus less valuable to the board, which makes the results much easier to interpret compared to a traditional interaction model. The effect of opportunism for each group is reported directly, instead of the incremental effects when estimating main and interaction effects (Christensen et al., 2013).

Table 7 displays the results of this testing procedure. As expected, results show that opportunistic insider selling is not associated with turnover for valuable directors, while less valuable directors’ opportunistic selling behavior is positively and significantly associated with their likelihood of turnover. This difference in treatment between valuable and less valuable directors is significant at the 1% level (p-value = 0.0036). Control variables added in Table 7 are in line with Table 6. In the next three columns, each source of director value (i.e. KEY DIRECTORi,j,t; ACFEi,j,t or EXECUTIVEi,j,t) is considered separately. Each model tests one determinant of director value and compares director turnover following opportunistic selling to the group of less valuable directors. Looking at each of these director characteristics separately, the results confirm that opportunistic insider selling is positively and significantly associated with director turnover only when directors are not classified as valuable. Taken together, results in Table 7 strongly support Hypothesis 2 as our findings show that the association between insider selling behavior and turnover is not significant for valuable directors.

Finally, Table 8 presents the multivariate results testing whether the association between insider selling and director turnover for valuable and less valuable directors depends on the size of the firm. In this analysis, we categorize our observations into four different groups (Valuable = 0 and LARGEj,t = 0; Valuable = 1 and LARGEj,t = 0; Valuable = 0 and LARGEj,t = 1; Valuable = 1 and LARGEj,t = 1) and estimate separate coefficients for each group. Given the third hypothesis, we expect the difference in director turnover following opportunistic selling between valuable and less valuable directors to be smaller in larger versus smaller firms. This means that the difference in coefficients between the first two groups (i.e. Valuable = 0 and LARGEj,t = 0 versus Valuable = 1 and LARGEj,t = 0) is expected to be larger than the difference in coefficients between the last two groups (i.e. Valuable = 0 and LARGEj,t = 1 versus Valuable = 1 and LARGEj,t = 1).

Looking at the coefficients of each group separately, we indeed observe that the results presented in Table 7 only hold in smaller firms. The results of Model 1 show that in smaller firms, valuable directors do not face a positive and significant association between turnover and opportunistic insider selling while less valuable directors do. However, in larger firms, there is a positive and significant association between opportunistic insider selling and director turnover for directors classified as valuable as well as less valuable. To test whether the difference in coefficients across groups is significant, we report Wald-tests at the bottom of Table 8. Consistent with Hypothesis 3, results show that the difference in coefficients between valuable and less valuable directors is indeed smaller in larger firms compared to smaller firms. This seems to suggest that for larger firms, legitimacy and legal risk concerns potentially outweigh concerns regarding director replaceability. Finally, columns 2–4 present models looking at different sources of director value. Results are similar to those presented in model 1 when directors derive their value from occupying a key position in the board or possessing accounting financial expertise. However, executive directors do not seem to experience increased levels of turnover following opportunistic insider selling, regardless of the size of their firm. This result potentially indicates that executive directors are deeply embedded in the firm.

Taken together, results in Tables 6, 7, and 8 show that opportunistic insider selling is associated with a higher likelihood of subsequent director turnover. However, we find no evidence of this association for valuable directors (i.e. executives, key directors and accounting experts) in smaller firms. In larger firms however, key directors and accounting experts have a similar likelihood of being replaced as less valuable directors. Interestingly, the likelihood of turnover for executives is not linked to opportunistic insider in small nor large firms.

Additional Analyses and Robustness Checks

To enhance the validity of our results we perform several sensitivity and robustness checks. First, we test the robustness of our results using alternative proxies for director turnover and opportunistic insider selling. Second, we explore whether adding additional control variables alters the main results. Finally, we attempt to address the potential impact of endogeneity on our results using entropy balancing as well as different fixed effects specifications.

Alternative Measurement of the Dependent and Test Variable

To ensure the robustness of our results, we conduct our main analyses using an alternative measure of opportunistic selling based on transaction profitability. We measure transactions’ abnormal return over a 180-day window and multiply abnormal returns by − 1 to reflect abnormal profits earned by insiders (Dai et al., 2015; Hillier et al., 2015; Ravina & Sapienza, 2010). Data requirements for calculating returns following insiders’ transactions reduce our sample from 49,597 director-firm-years to 12,825 director-firm-years. We rank insider sales into quartiles based on transaction profitability and label directors as “opportunistic” in a given firm-year if they have transactions in the top quartile of profitability in the relevant fiscal year.Footnote 27 Using this alternative measure for insider selling opportunism, 15.70% of directors are classified as opportunistic. Untabulated regression results provide consistent evidence for H1 and H2. We find a positive association between insiders with sales in the top quartile of profitability and their likelihood of turnover (p-value = 0.030) and this effect is most prevalent for directors who are less valuable (p-value = 0.007). The Wald test for differences in coefficients confirms the difference in treatment between valuable and less valuable directors (p-value = 0.0511). Results for H3 are somewhat mixed. Our Wald tests for differences in coefficients indicate no significant difference in director treatment across large and small firms although the individual effects overall remain significant, i.e. only valuable directors in small firms do not experience a significant and positive association between their likelihood of turnover and highly profitable insider selling behavior.

Furthermore, the robustness of the results is tested using a 1-year turnover window instead of a 3-year turnover window. Results (untabulated) are similar to those reported in our main tables. We find a positive and significant association between directors’ opportunistic insider selling and their likelihood of turnover (p-value = 0.013). The coefficient of opportunistic insider selling is significant only for less valuable directors (p-value = 0.001), but not for valuable directors (p-value = 0.637). The difference between both groups is statistically significant (p-value = 0.003). We find that even when we measure turnover over a 1-year window, the difference in treatment between valuable and less valuable directors is significantly smaller in large firms compared to small firms (p-value = 0.025).

Additional Control Variables

As a robustness check, we introduce several additional control variables, i.e. overall selling behavior of the director, director anticipation of turnover, and social ties to the CEO. First, we control for the overall selling behavior of a director by creating an additional variable measuring the proportion of shares sold by the director to the total numbers of shares outstanding in the firm (measured in millions). After including this additional control, we still find a positive and significant association between directors’ opportunistic insider selling and likelihood of turnover (p-value = 0.000). Although this effect is significant for both valuable (p-value = 0.001) and less valuable directors (p-value = 0.049), there is still a significant difference between both groups (p-value = 0.004). Consistent with our third hypothesis, this difference in treatment between valuable and less valuable directors is smaller in large firms compared to small firms (p-value = 0.018).

Second, we investigate the influence of director age as it seems possible that directors anticipating their turnover increase their selling at the next opportunity and erroneously have more sales classified as opportunistic. This is not necessarily opportunistic behavior, as insiders building down their stockholdings at the end of their mandate is unlikely to be information-based. To examine this relationship, we measure the impact of opportunistic sales conditional on directors being in the highest quartile of tenure or age within their board in any given year. Although the oldest directors and those with the longest tenure have a significantly higher rate of turnover in the board, they are not more likely to be replaced following opportunistic insider selling than their younger and shorter-tenured counterparts. While opportunistic insider selling behavior is still positive and significantly associated with turnover for younger directors (p-value = 0.009) and shorter tenured directors (p-value = 0.000), it is only marginally significant for older directors (p-value = 0.096), and insignificant for directors with longer tenure (p-value = 0.230). Taken together these results indicate that it is unlikely that our results are endogenously explained by directors increasing their opportunistic selling behavior in anticipation of the end of their position on the board. Furthermore, as the main results can be attributed to the younger group of directors, they are more likely to be explained by unexpected or forced turnover instead of expected or planned turnover (Fahlenbrach et al., 2017).

Third, as CEOs have substantial influence on who occupies the board (e.g., Carcello et al., 2011; Cohen et al., 2008, 2011; Khanna et al., 2015), we focus on directors’ social ties with their CEOs as a measure of firm-specific relational capital. Such connections are highly beneficial to management as they are associated with increased CEO compensation, less effective oversight, and a reduced likelihood of CEO dismissal in cases of fraud (Bruynseels & Cardinaels, 2014; Coles et al., 2014; Hwang & Kim, 2009; Khanna et al., 2015). We define friendship ties as shared past or present memberships in non-professional organizations, such as charities, country clubs, or other non-profit associations (Bruynseels & Cardinaels, 2014).Footnote 28 In line with expectations, we find that directors who share a social connection with the CEO do not face a positive and significant association between their likelihood of turnover and opportunistic insider selling behavior (p-value = 0.701), while this association is significant for directors without this connection (p-value = 0.000).

Endogeneity

Finally, to avoid underlying differences in the characteristics of directors or firms engaged in opportunistic insider selling compared to those who are not, we re-estimate our main regressions using an entropy balanced sample.Footnote 29 The entropy balancing procedure weighs control sample observations to adjust for differences in the distributions of the treatment and control groups (Hainmueller, 2012). Untabulated results confirm a positive association between opportunistic insider selling and director turnover (p-value = 0.004), a result which can be attributed to less valuable (p-value = 0.000), but not valuable directors (p-value = 0.148). This difference in the association between opportunistic insider selling and turnover is significantly larger in smaller firms compared to larger firms (p-value = 0.020).

As an alternative for entropy balancing, we add director fixed effects to control for potential omitted time-invariant director characteristics which may influence both the likelihood of director turnover and/or opportunistic selling behavior. Overall, the association between opportunistic insider selling and director turnover remains significant (p-value = 0.012) and seems to be concentrated in less valuable directors (p-value = 0.017) compared to valuable directors (p-value = 0.161). When exploring the effect of firm size, our results are consistent with our main analyses. Wald tests for differences in coefficients confirm that the likelihood of director turnover following opportunistic selling is larger in small versus large firms (p-value = 0.077).

Finally, we address the concern that firm-specific factors in a given year (such as poor firm performance) might cause director turnover as well as insider selling. Specifically, we estimate our models including firm-year fixed effects. By removing all inter firm-year variation, these models investigate whether intra firm-year variation in director turnover is associated with intra firm-year variation in opportunistic insider selling behavior. We find similar results for H1 and H2, i.e. opportunistic insider selling is positively associated with director likelihood of replacement (p-value = 0.049). This positive association is significant for less valuable directors (p-value = 0.016), but not for valuable directors (p-value = 0.705). When distinguishing between small and large firm, we only find a significant association between opportunistic insider selling and turnover for less valuable directors at larger firms. However, our Wald tests for differences in coefficients remain in line with the main results.

Conclusion

The importance of limiting unethical opportunistic insider selling is a concern of regulators, investors, and firms. In this paper, we investigate whether director opportunistic insider selling is associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent director turnover. As such, we are the first to examine potential labor market consequences of opportunistic insider selling among directors. Previous literature on director turnover has shown that board ineffectiveness (e.g., restatement, fraud, investigation by the SEC, option backdating, disclosures of internal control material weaknesses) increases the likelihood of director turnover (Arthaud-Day et al., 2006; Ertimur et al., 2012; Fich & Shivdasani, 2007; Johnstone et al., 2011; Srinivasan, 2005). However, it is unknown whether an individual director’s undesirable behavior is associated with his or her likelihood of turnover.

We argue that there are at least two reasons why firms may want to avoid director opportunistic insider selling. First, opportunistic insider selling is generally perceived as unethical and unfair. As such, it may lead to negative public sentiment and reputational costs that can damage organizational legitimacy (Cui et al., 2015; Gao et al., 2014; Harris, 2007; Sullivan et al., 2007). Second, insiders exploiting negative private information expose the firm to legal risk (Dai et al., 2016). Given that companies want to minimize their legal risk and protect their legitimacy, we expect a higher likelihood of director turnover for directors engaging opportunistic insider sales. However, director turnover decisions after opportunistic insider selling are likely to be influenced not only by the cost of retaining the director, but also by his/her replacement cost. Therefore, we expect the likelihood of director turnover to vary with their value to the firm, as well as with firm visibility (size).

We test these predictions using a sample of 11,409 directors in 2280 firms from 2005 to 2014. Our results show that opportunistic insider selling, is associated with a higher likelihood of director turnover for some directors, but not all. We find evidence that in smaller firms, the association between director turnover and opportunistic trading is non-existing for directors who are especially valuable to the board or costly to replace. When firms are larger, both valuable and less valuable directors are significantly more likely to leave the board following opportunistic insider selling behavior, although an exception seems to be made for executive directors who do not experience increased turnover rates. This indicates that for large firms, concerns regarding legal risk and firm legitimacy outweigh director replacement costs. Overall, our results seem to indicate that replacement of directors engaging in opportunistic insider selling is likely to be the result of a careful cost–benefit analysis, taking into account director value to the firm as well as firm visibility.

The results presented in this study contribute to the literature in multiple ways. First, we are the first to provide systematic evidence of an association between director opportunistic insider selling and subsequent turnover from the board. Our findings suggest that firms tend to self-regulate unethical behavior by their insiders, although not equally so across directors and firms. Probing deeper into this issue, our results shed some light on how director retention and replacement costs may influence the turnover likelihood of a director engaging in unethical behavior. Specifically, they seem to suggest that firms try to minimize legal risk and protect board legitimacy by distancing themselves from directors displaying unethical behavior, but only when director replacement costs do not outweigh director retention costs.

The results in this study provide a foundation for further investigation of the relationship between director turnover and opportunistic insider selling behavior. For example, the decision to replace a director engaging in opportunistic behavior might not only influence the future behavior of this particular director, but also of other board members. Director turnover following opportunistic selling may be interpreted by the remaining directors as a signal that opportunistic behavior will not be accepted by the firm. Using an event study methodology, it would be interesting to investigate how director turnover potentially influences other directors’ future insider selling behavior.

Second, future research may focus on the potential reputational damage associated with director turnover following opportunistic insider selling. Does director turnover associated with unethical behavior in one firm result in a loss of board seats in other firms? Are these directors less likely to acquire new board seats in the years following turnover? Furthermore, following the insider trading literature, profits from inside information can be seen as a part of director and executive compensation. Indeed, firms imposing restrictions on insider trading behavior subsequently experience significant rises in executive compensation (Roulstone, 2003). If firms were to actively oust opportunistic insider traders from the board, this would limit directors’ ability to realize insider trading profits and reduce their expected benefits from board positions. Thus, while the replacement of opportunistic directors safeguards firm legitimacy concerns, it also might limit the firms’ capacity to attract talented executives and directors. As such, future research might investigate the impact of firms developing a reputation for active monitoring of opportunistic insider selling on recruitment and remuneration of future directors and executives.

This study is subject to some limitations. Though we find a link between opportunistic insider selling and director turnover, we cannot observe the exact nature of the turnover. As a result, we cannot distinguish between voluntary and forced director turnover. It is thus impossible for us to demonstrate actual disciplinary director turnover following opportunistic insider selling. The observed turnover might be due to age, tenure restrictions, or other limitations in the firms’ code of conduct. To alleviate some of these concerns, we control for director tenure and time until retirement. Further, all opportunistic trades are treated equally in our turnover analysis. The potential impact of these opportunistic trades on firm legitimacy, however, will vary. An insider acting on non-public information that is potentially material will be punished more severely than an insider placing opportunistic trades based on less price-relevant information.

Data availability

All data are available from the sources identified in the text.

Notes

These regulatory initiatives include Rule 10b-5 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the Insider Trading and Securities Fraud Enforcement Act, and the Stock Enforcement Remedies and Penny Stock Reform Act.

Insiders are here defined as directors, officers, or owners of more than 10% of a class of equity securities registered under Section 12.

To this end, they must file a Form 4 through the SEC’s EDGAR system within two business days. With this form filing, the information is publicly available to investors, including the amount purchased or sold and the price per share. Often insider trading activities reported on Form 4 filings are further disseminated through the financial press (Dai et al., 2015). In addition, there are various websites that publicly, and free of charge, aggregate and visualize transactions by company insiders.

Our focus in this study is on opportunistic selling by insiders because this type of transaction is often induced by private information regarding negative firm prospects (e.g., Fidrmuc et al., 2006). As such, opportunistic insider selling creates significant societal costs, benefits only insiders, and violates equal shareholder rights (Cohen et al., 2012; McGee, 2010). In line with this, recent research shows that firms more actively restrict insider sales compared to purchases (Dai et al., 2016) as these transactions are more prone to SEC investigation and litigation compared to insider purchases (e.g., Billings & Cedergren, 2015; Brochet & Srinivasan, 2014; Cheng & Lo, 2006; Dai et al., 2015, 2016).

Firms can achieve turnover either through directly dismissing a director or not nominating the director for renewal of their mandate. Throughout this paper we do not distinguish between these two channels of turnover.

Although insider trading information is publicly available and might be the reason for director turnover, firms are likely to adopt a neutral communication style when announcing director departure. Drawing attention to director opportunistic trading behavior might not only trigger SEC investigation but also pose a threat to firm reputation and legitimacy in itself. Indeed, prior research on director departures (Bar-Hava et al., 2021; Fahlenbrach et al., 2017) documents that firms and directors are very sparse in their communication regarding director departures and often do not communicate the underlying reason. Although firms are not likely to communicate openly about director misbehavior, they might still attempt to protect their reputation and legitimacy by dismissing directors engaging in unethical behavior behind closed doors.

The value of specific outside directors (and hence the cost of replacing them) is likely to be influenced by external factors that affect the demand for certain types of directors. For example, Linck et al. (2009) show that SOX’s specific requirements regarding directors with financial backgrounds has led to a substantial increase in demand for financial experts.

Results are similar when clustering standard errors at the director level or at the director-firm level.

The opportunistic nature of insider trades is not disclosed by the insider when they file their form 4 with the SEC. However, there are common insider trading data aggregator websites that provide graphical overviews of insiders’ trading behavior, one example would be SecForm4.com. The repetitive nature of routine transactions is highly visible on these platforms, making it much easier for outside investors to identify recurring patterns in insiders’ trading behavior.

We assign a value of 0 for OPP SALEi,j,t when directors only have purchase transactions in a given year. Results are similar if we use total shares traded as an alternative scale instead.

Specifically, Cohen et al. (2012) provide preliminary evidence that opportunistic (but not routine) sales increase the likelihood of SEC enforcement actions, which is consistent with the SEC’s use of data analysis tools to detect suspicious trading patterns. Moreover, Dai et al. (2016) provide evidence that well-governed firms actively restrict opportunistic insider selling activities identified using the Cohen et al. (2012) measure, and findings by Billings and Cedergren (2015) indicate that litigation risk increases with insider opportunistic selling.

Results are similar when we use the top quartile of market value as an alternative cutoff.

Results are identical when we use the natural logarithm of total assets at the beginning of the turnover window.

Cohen et al. (2012) suggest two methods to distinguish between opportunistic and routine trades, one at the trader level and one at the trade level, and show that both measures are equally effective. Although they do not provide descriptive statistics for their individual trade-level classification, at the trader level they classify 45.2% of all traders as opportunistic. When we apply the trader-level classification scheme, we also find that 43.9% of insiders in our sample classify as opportunists, which is very similar to the percentage reported by Cohen et al. (2012).

Non-independent directors are those not classified as independent by BoardEx, and consist amongst others of block holders, general counsel, officers, and non-independent board chairpersons.

Following Dai et al. (2016) we exclude transactions with less than 100 shares or those with trading prices less than $2, allowing us to focus on the more meaningful transactions.

We multiply the abnormal returns earned by − 1 to indicate abnormal profits from the insider sales transactions.

We define profitable transactions as those with a CAR greater than or equal to zero.

EXECUTIVEi,j,t maximum VIF = 2.30 and COMMITTEE MEMBERi,j,t maximum VIF = 4.53.

BOARD SIZEj,t variance inflation factor = 28.27; %INDEPENDENTj,t variance inflation factor = 63.35.

Test variables are unaffected in both cases and have a maximal variance inflation factor of 2.77 across analyses.

Marginal effects are similar when calculating average marginal effects or marginal effects with values fixed at their means.

In a traditional interaction analysis, we would estimate β1t OPP SALEi,j,t + β2t VALUABLEi,j,t + β3t OPP SALEi,j,t*VALUABLEi,j,t. Our analysis instead estimates β1 OPP SALEi,j,t when VALUABLEi,j,t = 0 + β2 OPP SALEi,j,t when VALUABLEi,j,t = 1 such that β1 = β1t and β2 = β1t + β3t. This approach allows for a direct test of the effect total of OPP SALEi,j,t for both groups identified by VALUABLEi,j,t.

On average we can only determine returns for 46.57% of shares traded in a fiscal year. Consequently, it would not be appropriate to use the ratio of shares sold with high profits to shares traded as our measure of opportunism, as the computation of this measure would not be based on complete transaction return information.

We estimate this regression using a restricted sample without CEO’s. Results remain similar when including these observations.

Specifically, we determine the optimal observation weights before each individual analysis and require that the three first moments (i.e. covariate means, variances, and skewness) are equal using a tolerance level of 0.015. We generate a new binary variable OPP SOLDi,j,t measuring 1 when director i opportunistically sells shares in firm j in fiscal year t and 0 otherwise. We then use OPP SOLDi,j,t as a treatment variable and balance covariate differences between directors engaging in opportunistic selling and directors not engaging in this behavior. We re-balance our sample for each individual regression.

References

Abdolmohammadi, M., & Sultan, J. (2002). Ethical reasoning and the use of insider information in stock trading. Journal of Business Ethics, 37, 165–173.

Aboody, D., Hughes, J., & Liu, J. (2005). Earnings quality, insider trading, and cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 43, 651–673.

Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. (2008). Do directors perform for pay? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 46(1), 154–171.

Agrawal, A., & Cooper, T. (2015). Insider trading before accounting scandals. Journal of Corporate Finance, 34, 169–190.

Agrawal, A., Jaffe, J. F., & Karpoff, J. M. (1999). Management turnover and governance changes following the revelation of fraud. Journal of Law and Economics, 42, 309–342.

Alam, Z. S., Chen, M. A., Ciccotello, C. S., & Ryan, H. E. (2018). Board structure mandates: Consequences for director location and financial reporting. Management Science, 64(10), 4735–4754.

Arthaud-Day, M. L., Certo, S. T., Dalton, C. M., & Dalton, D. R. (2006). A changing of the guard: Executive and director turnover following corporate financial restatements. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 1119–1136.

Asthana, S., & Balsam, S. (2010). The impact of changes in firm performance and risk on director turnover. Review of Accounting and Finance, 9(3), 244–263.

Badertscher, B. A., Hribar, S. P., & Jenkins, N. T. (2011). Informed trading and the market reaction to accounting restatements. The Accounting Review, 86(5), 1519–1547.

Badolato, P., Donelson, D. C., & Ege, M. (2014). Audit committee financial expertise and earnings management: The role of status. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58(2–3), 208–230.

Bar-Hava, K., Huang, S., Segal, B., & Segal, D. (2021). Do independent directors tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth when they resign? Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 36(1), 3–29.

Beneish, M. D., Marshall, C. D., & Yang, J. (2017). Explaining CEO retention in misreporting firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 123, 512–535.

Beneish, M. D., Press, E., & Vargus, M. E. (2012). Insider trading and earnings management in distressed firms. Contemporary Accounting Research, 29(1), 191–220.

Bettis, J. C., Coles, J., & Lemmon, M. (2000). Corporate policies restricting trading by insiders. Journal of Financial Economics, 57, 191–200.

Bhattacharya, U., & Daouk, H. (2002). The world price of insider trading. The Journal of Finance, 57, 75–108.

Billings, M. B., & Cedergren, M. C. (2015). Strategic silence, insider selling and litigation risk. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 59(2–3), 119–142.

Blankespoort, E., Miller, G. S., & White, H. D. (2014). The role of dissemination in market liquidity: Evidence from firms’ use of Twitter. The Accounting Review, 89(1), 79–112.

Brochet, F., & Srinivasan, S. (2014). Accountability of independent directors: Evidence from firms subject to securities litigation. Journal of Financial Economics, 111, 430–449.

Bruynseels, L., & Cardinaels, E. (2014). The audit committee: Management watchdog of personal friend of the CEO? The Accounting Review, 89, 113–145.

Cao, Y., Myers, J. N., Myers, L. A., & Omer, T. C. (2015). Company reputation and the cost of equity capital. Review of Accounting Studies, 20(1), 42–81.

Carcello, J. V., Hermanson, D. R., & Ye, Z. (2011). Corporate governance research in accounting and auditing: Insights, practice implications, and future research directions. Auditing A Journal of Practice & Theory, 30(3), 1–31.

Chang, M., & Lim, Y. (2016). Late disclosure of insider trades: Who does it and why? Journal of Business Ethics, 133, 519–531.

Cheng, Q., & Lo, K. (2006). Insider trading and voluntary disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research, 44(5), 815–848.

Chidambaran, N. K., Liu, Y., & Prabhala, N. R. (2015). Director turnover heterogeneity. Working paper.

Christensen, H. B., Hail, L., & Leuz, C. (2013). Mandatory IFRS reporting and changes in enforcement. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 56, 147–177.

Chyz, J. A., & Gaertner, F. B. (2017). Can paying “too much” or “too little” tax contribute to forced CEO turnover? The Accounting Review, 93(1), 103–130.

Cline, B. N., Gokkaya, S., & Liu, X. (2017). the persistence of opportunistic insider trading. Financial Management, 46(4), 919–964.

Cohen, J. R., Gaynor, L. M., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. (2011). The impact on auditor judgments of CEO influence on audit committee independence and management incentives. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 30(4), 129–47.

Cohen, J. R., Hoitash, U., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. M. (2014). The effect of audit committee industry expertise on monitoring the financial reporting process. The Accounting Review, 89(1), 243–273.

Cohen, J. R., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. (2008). Form versus substance: The implications for auditing practice and research of alternative perspectives on corporate governance. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 27(2), 181–98.

Cohen, L., Malloy, C., & Pomorski, L. (2012). Decoding inside information. The Journal of Finance, 67, 1009–1043.

Coles, J., Daniel, N., & Naveen, L. (2014). Co-opted boards. Review of Financial Studies, 27, 1751–1796.

Cowen, A. P., & Marcel, J. J. (2011). Damaged goods: Board decisions to dismiss reputationally compromised directors. Academy of Management Journal, 54(3), 509–527.

Cui, J., Jo, H., & Li, Y. (2015). Corporate social responsibility and insider trading. Journal of Business Ethics, 130, 869–887.

Dai, L., Fu, R., Kang, J. K., & Lee, I. (2016). Corporate governance and the profitability of insider trading. Journal of Corporate Finance, 40, 235–253.

Dai, L., Parwada, J. T., & Zhang, B. (2015). The governance effect of the media’s news dissemination role: Evidence from insider trading. Journal of Accounting Research, 53(2), 331–366.

Duellman, S., Guo, J., Zhang, Y., & Zhou, N. (2018). Expertise rents from insider trading for financial experts on audit committees. Contemporary Accounting Research, 35(2), 930–955.

Erkens, D. H. & Bonner, S. E. (2013). The role of firm status in appointments of financial experts to audit committees. The Accounting Review, 88, 107–136.

Ertimur, Y., Ferri, F., & Maber, D. A. (2012). Reputation penalties for poor monitoring of executive pay: Evidence from option backdating. Journal of Financial Economics, 104(1), 118–144.

Fahlenbrach, R., Low, A., & Stulz, R. M. (2017). Do independent director departures predict future bad events? The Review of Financial Studies, 30(7), 2313–2358.

Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325.

Farrell, K., & Whidbee, D. A. (2003). The impact of firm performance expectations on CEO turnover and replacement decisions. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 36, 165–196.

Fassin, Y. (2005). The reasons behind non-ethical behavior in business and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics, 60(3), 265–279.

Ferris, S., Jagannathan, M., & Pritchard, A. (2003). Too busy to mind the business? Monitoring by directors with multiple board appointments. Journal of Finance, 58, 1087–1111.