Abstract

Fair trade has been researched extensively. However, our understanding of why consumers might be reluctant to purchase fair trade goods, and the associated potential barriers to the wider adoption of fair trade products, is incomplete. Based on data from 409 USA participants, our study demonstrates some of the psychological processes that underlie the rejection of fair trade products by conservatives. Our findings show that political conservatism affects fair trade perspective-taking and fair trade identity, and these latter two subsequently affect fair trade purchase intention. The decrease in fair trade perspective-taking and fair trade identity are two psychological features that potentially shield conservatives from the appeals of fair trade products. We extend prior research on the effects of political ideology on consumption not only by demonstrating the predisposition of highly conservative consumers towards prosocial consumption, but also by showing the internal functioning of the conservative decision-making process. We further demonstrate that the effect of conservatism on fair trade purchase deliberation is moderated by age and income. Age reduces the negative effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking, whereas income heightens the negative effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking. Our results suggest that fair trade initiatives can target the conservative consumer segment in high-income countries with a greater chance of success when applying marketing strategies that make perspective-taking redundant and that aim at younger consumers with lower incomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Political conservatism and its effect on consumption is an increasingly important research topic in marketing. Studies so far have either operationalised conservatism as an obstacle, for example, to the consumption of international brands (Khan et al. 2013), complaint behaviour (Jung et al. 2017a), and the horizontal differentiation through commodities (Kim et al. 2018; Ordabayeva and Fernandes 2018); or have examined how group norms (Fernandes and Mandel 2014; Kaikati et al. 2017) and appeals (Kidwell et al. 2013) diminish the inhibitory effect of conservatism on consumption. Our study contributes to the literature on conservatism as a potential obstacle to prosocial consumption through a conceptual elaboration and the methodological evaluation of the psychological processes that mediate between conservatism and its restrictive effects on consumption. A better understanding of the process that accounts for the decrease in the willingness of conservatives to buy would help to market products that are politically framed.

The marketing of fair trade products tends to be politically framed and raises issues of public concern by encouraging consumers in high-income countries (HIC) to fight against poverty through their expenditure (Wempe 2005). For instance, a typical fair trade marketing campaign often involves persuading consumers to consume fair trade coffee as a way to contribute to the improvement of living conditions of coffee bean farmers in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). In effect, such promotion of fair trade invites consumers to take a political stance against inequality and the exploitation of agricultural farmers. Despite the prominent political nature of fair trade marketing, however, it remains unclear how such politicised marketing messages affect consumer decision making.

Our analysis identified two psychological factors that mediate the relationship between political conservatism and fair trade purchase intention, thereby enriching the current state of the literature on the effect of political ideology on consumption. Furthermore, we examined the boundary conditions of the relationship between political ideology and fair trade perspective-taking to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how the marketing of fair trade products could be enhanced. In doing so, this study offers a managerial contribution to market segmentation by demonstrating how age and income levels moderate the process that generates negative evaluations of fair trade products.

Targeting conservative consumers as a new market segment could help to increase sales figures of fair trade products. The global retail sales value of Fairtrade International was 8.5 billion U.S. dollars in 2017 (FairtradeInternational 2018a). In the same year, the global retail market was valued at 26.6 trillion U.S. dollars (HKExnews 2018). This illustrates that the revenue from fair trade products is comparatively small.

In the following, we describe the literature relevant for our research so as to derive hypotheses. We then outline our methodological approach before introducing the measurement instruments. Next, we present and discuss the results. Finally, we discuss the managerial and academic implications of our research on business ethics.

Theory and Hypotheses

The World Fair Trade Organization, Fairtrade International and FLO-CERT (FairtradeInternational 2011) define fair trade as ‘a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade’ (p. 1). Extant studies on fair trade consumption often highlighted budgetary restrictions as a hurdle to fair trade consumption, as fair trade products are often sold at higher prices than their non-fair-trade counterparts (Andorfer and Liebe 2012). Such studies investigated the willingness of consumers to pay a premium for fair trade coffee (Van Loo et al. 2015), chocolate (Vlaeminck et al. 2016), and sweatshop-free clothing (Phau et al. 2017). Yet, these hurdles are not unique to fair trade products. Organic products, for example, are also priced at a premium but are significantly more successful than fair trade products as global sales of organic food and drink surpassed 100 billion U.S. dollars in 2018 (EcoviaIntelligence 2019) in comparison to the global retail sales value of Fairtrade International at 8.5 billion U.S. dollars in 2017 (FairtradeInternational 2018a). As such, it is likely that consumer resistance to fair trade consumption may be about more than just budgetary considerations.

In addition to the existing research, we use political ideology as a theoretical lens to investigate obstacles to the consumption of fair trade products. In effect, the study positions fair trade consumption at the intersection of consumer psychology and political psychology. Both research areas show an impressive body of findings and have produced valuable insights into why people buy specific products and how political ideologies are characterised. We describe these earlier studies next and how they relate to the focus of our research.

Conservatism and Consumption

The field of political psychology is largely in agreement that the polarisation between conservative and liberal ideologies captures the core essence of Western political life (Jost 2017). Political ideologies are activated when individuals are exposed to unfamiliar stimuli (Jost 2017). Conservatism emerges as a rightist belief system that focuses on hierarchy and tradition, while liberalism reflects a leftist ideology that prioritises equality and progress (Jost 2017). More specifically, political conservatism is conceptualised as an ideological belief system that consists of two core components: resistance to change and opposition to equality (Jost et al. 2007, p. 990). Both core components of political conservatism may result in the same purchase decision being made, but because of different motivational goals (Jung and Mittal 2020). In addition to the two core components of political conservatism, the peripheral components of political conservatism list attitudes concerning issues (e.g. military spending, size of government, immigration policies) that are understood to represent conservatism in a certain culture and at a certain place and time (Jost 2006; Jost et al. 2003b). Peripheral aspects of political conservatism could differ between, for example, the USA and Western European countries because US Americans tend to be more individualistic and less supportive of a robust safety net than citizens in Spain, Germany, France, and Britain (PewResearchCenter 2012). Conversely, the core aspects of conservatism represent a more stable predisposition that resonates with people’s underlying needs, interests and goals (Jost 2006; Jost et al. 2003b). Core and peripheral aspects of political conservatism form a social-cognitive theory of conservatism (Jost et al. 2003b), which is not to be equated with political partisanship or voting behaviour.

Studies regularly find that the conservative ideology is manifested in the routines of consumers as they, for instance, prefer national brands over generic substitutes and are less likely to purchase newly launched consumer goods (Khan et al. 2013). Conservatives are also less likely to complain and to challenge complaint resolutions than liberals (Jung et al. 2017a). This is because conservatives are more motivated than liberals to apply system justification, which was the mediator in Jung et al.’s (2017a) emerging model. Jung et al. suggest (2017b) that future explorations of prosocial behaviours might usefully focus on mechanisms like system justification, which undergird the behaviour of liberals and conservatives. Our study put this suggestion into practice and examined mechanisms that could mediate between political ideology and fair trade consumption.

Conservatism and Fair Trade

The conservatives’ preferences for entrepreneurial and free market-based solutions to social problems (Jost et al. 2003a) may indicate an acceptance of fair trade, especially as compared to aid. However, the pronounced stance of fair trade marketing that promotes equality within the supply chain may incite a more immediate reaction amongst conservatives to evaluate such political stance against their ideology that endorses inequality (Jost et al. 2003b). For example, the FairtradeFoundation (2019) states on its website that ‘fairtrade addresses the injustices of conventional trade, which traditionally discriminates against the poorest, weakest producers’, thus illustrating its transparent advocacy for a fairer marketplace. The idea that the market requires intervention in the shape of consumers paying a premium for fairer wages for LMIC workers is also likely to generate tension against the conservatives’ tendency to resist change (Jost et al. 2003b). Such conflicting ideology, therefore, is likely to result in the rejection of fair trade products by conservatives as a form of objection towards an opposing politicised marketing message.

The present research seeks to examine the nature of the conservatives’ predisposition towards fair trade labels by examining the psychological factors that mediate such a prosocial purchase evaluation. Our choice of mediators is based on the characteristics of conservatism, which promote both resistance to change and endorsement of inequality. First, the forces of a group provide a type of stability (Lewin 1952), which accounts for conservatives’ resistance to changing their behaviour and attitudes so as not to leave a social reality they are comfortable with (Jost 2015). Second, equal relations between groups do not exist because the ingroup favouritism of dominants is stronger than the ingroup favouritism of subordinates (Sidanius and Pratto 1999). Conservatives who promote the endorsement of inequality strive to maintain this asymmetrical ingroup bias and utilise such ingroup preference as a reference point in order to allocate their favour. Such an inward-looking characteristic of political conservatism, therefore, may affect the conservatives’ ability to take the perspective of outgroups (such as workers in LMICs) and their willingness to identify with a fair trade message that is incongruent with their beliefs towards a particular social structure. As such, the following sections examine the mediating roles of fair trade perspective-taking and fair trade identity on the relationship between political conservatism and the consumers’ intention to purchase fair trade products.

Fair Trade Perspective-Taking

Perspective-taking is defined as the ability of individuals to anticipate the reactions and the behaviour of others (Davis 1983). It involves the active consideration of the subjective experiences and mental states of outgroup members (Todd and Galinsky 2014). Perspective-taking can lead individuals with a high degree of ingroup identification to favour the outgroup less (Tarrant et al. 2012). This means, in the context of ideology, that liberals tend to adopt perspectives of ethnic/racial outgroups more frequently and show lower degrees of ethnic bias relative to conservatives (Sparkman and Eidelman 2016). As such, liberals are less likely than conservatives to show ethnic bias because of their greater ability to adopt the perspectives of ethnic/racial outgroups (Sparkman and Eidelman 2016). Fair trade packaging and campaigning materials often illustrate the problems of workers in LMIC (Staricco 2016) and may, therefore, be more effective for liberals than for conservatives. In the context of consumption, we postulate that conservatives are less likely than liberals to take the perspective of farmers or workers in LMIC, which in turn would negatively affect their intention to buy fair trade products. The unwillingness to purchase fair trade products represents a form of intergroup bias that results from the conservatives’ inability to take the perspectives of farmers and workers from LMIC. Thus, we hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 1:

Fair trade perspective-taking mediates the negative relationship between political conservatism and the willingness to buy fair trade products.

Fair Trade Identity

Identity theory suggests that ‘one’s self-concept is organised into a hierarchy of role identities that correspond to one’s positions in the social structure’ (Charng et al. 1988, p. 304). Based on this suggestion, we define fair trade identity as the internalisation of the fair trade concept into one’s self-concept as a set of role expectations about one’s consumer behaviour. This fair trade identity corresponds to the social structure of individuals. Social structures are an external source of identity (Stryker and Burke 2000). Society is a mosaic of relationships and interactions, which is organised by groups, communities, institutions, and organisations and which is intersected by boundaries of gender, age, ethnicity, religion, class, and other aspects (Stryker and Burke 2000). Such social structures influence social networks, in which people live through taking on roles (Stryker and Burke 2000). Identities internalise roles that are expected to be performed by individuals (Stryker and Burke 2000).

We see political ideology as a social structure as it constitutes boundaries that divide people into liberals and conservatives. Influenced by political ideology as a dividing social structure, conservatism is a social network of likeminded people, whereby the conservative beliefs determine the roles being played. One set of roles relates to the consumption of fair trade products. Thus, we expect fair trade identity to mirror conservatism as part of a self-concept. Again, the core aspects underlying conservative beliefs contradict the concept of fair trade. Consequently, we expect that political conservatism decreases the internalisation of the fair trade concept. We define such disidentification as the ‘consumer’s active rejection of and distancing from’ (Josiassen 2011, p. 125) the fair trade concept. The disidentification of consumers has been researched in a number of contexts. Josiassen (2011) found that the repulsion of consumers toward the country in which they live reduces the shopping for goods produced in that country. Wolter et al. (2016) demonstrated that self-brand dissimilarity, brand disrepute, and brand indistinctiveness positively relate to consumer-brand disidentification which then positively relates to brand opposition intentions. The present study extends the existing research on disidentification as it investigates disidentification in a politicised consumption environment.

Furthermore, we draw upon the concept of behaviour as an expression of identity (Stryker and Burke 2000). This is based on a comparison between the meaning of an identity and the meaning of a behaviour (Burke and Reitzes 1981). If the meaning of the identity and the meaning of the behaviour correspond, the identity predicts the behaviour (Burke and Reitzes 1981). In the context of our research, this means that an individual that categorises themselves as a fair trade type of person has a positive stance on the concept of fair trade. Similarly, a consumer intending to purchase fair trade products supports the idea of making fair trade goods part of the shopping cart. Both the fair trade identity, as well as the fair trade purchase intention, correspond in their positive meaning towards fair trade. Therefore, we expect that fair trade identity predicts fair trade purchase intention. However, we predict that the positive effect of consumers’ fair trade identity on the willingness to buy fair trade products is outweighed by the negative effect of political conservatism. Therefore:

Hypothesis 2:

Fair trade identity mediates the negative relationship between political conservatism and the willingness to buy fair trade products.

Additionally, we draw upon the concept of self-processes as an internal source of identity (Stryker and Burke 2000). Affects and emotions are included in the internal self-process as they have consequences for those experiencing them (Stryker and Burke 2000). Perspective-taking is a facet of empathy (Davis 1983) and thus within the scope of affects and emotions. Therefore, we consider fair trade perspective-taking to be an internal self-process that influences the fair trade identity. More generally, we realise ourselves only as we recognise other people in their relation to us (Mead 1934/1972). This means that in taking someone else's attitude, an individual realises their own self (Mead 1934/1972). A self cannot be experienced only by itself (Mead 1934/1972) but it can, for example, be experienced by taking the perspective of farmers or workers in LMIC into account. The demonstration of fair trade perspective-taking as an internal source of fair trade identity would show that the view from the outside, i.e. from poor farmers, informs the view on the inside, i.e. on the self.

Hypothesis 3:

The ability to take on the perspective of farmers or workers in LMIC is positively related to fair trade identity.

Individual Characteristics

Finally, we investigate two individual characteristics as potential boundary conditions: age and income. In particular, we expect that age and income affect the magnitude of the relationship between political ideology and fair trade perspective-taking. Research findings demonstrate that greater age predicts greater conservatism (Feather 1979; Ray 1985). In particular, conservatism scores rapidly increase within the fifth life decade (Truett 1993). Given that, we posit that a lower age diminishes the negative effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking.

Hypothesis 4:

Younger age diminishes the negative effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking.

Blader et al. (2016) pointed out that high power decreases perspective-taking, whereby power is understood as someone's control over resources. For example, Galinsky et al. (2006) demonstrated across four studies that power reduces the focus on other people’s psychological experiences. We consider income as power because salaried employees gain control over financial resources. Consequently, an increasing income is expected to enhance the negative effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking.

Hypothesis 5:

Higher income enhances the negative effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking.

The conceptual model of an indirect relationship between political conservatism and fair trade purchase intention is shown in Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of an indirect relationship between political conservatism and fair trade purchase intention. H1 refers to the hypothesis of the mediating effect of fair trade perspective-taking on the relationship between conservatism and fair trade purchase intention. H2 refers to the hypothesis of the mediating effect of fair trade identity on the relationship between conservatism and fair trade purchase intention. H3 refers to the hypothesised effect of fair trade perspective-taking on fair trade identity. H4 and H5 refer to the hypothesised moderation effects of age and income, respectively, on the relationship between conservatism and fair trade perspective-taking

Methodology

A survey was conducted to investigate the effects of political conservatism on fair trade purchase intention. Participants for this survey were recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk for cash payment ($1.00). MTurk is considered a valid subject pool for psychological studies on topics of political ideology because it has been demonstrated that conservatives and liberals in a MTurk sample mirrored the psychological split of conservatives and liberals in two USA national samples (Clifford et al. 2015).

According to estimated retail sales, the UK was the largest market for fair trade products in 2017 at about 2.013 million Euros, just ahead of Germany with about 1.329 million Euros, and the USA with about 994 million Euros (FairtradeInternational 2018b). This indicates major hurdles for fair trade consumption among US consumers. Against this background, the population of the USA is targeted by this study. Consequently, only MTurk workers from the USA were able to accept the task.

In order to avoid participation bias, the topic of fair trade was not mentioned when offering the task to MTurk workers. Moreover, to avoid common method bias, distinct scaling techniques, such as paired comparison as well as 5-point and 7-point Likert scales, were used. Finally, an attention check was included in the questionnaire so as to screen out random clicking.

Measurement Instruments

Issue-Based Conservatism

Prior marketing research (Kim et al. 2018; Winterich et al. 2012) measured political conservatism by use of a scale that assesses the self-reported political orientation on a right–left spectrum. The measurement of self-reported political orientation is questionable as people tend to overestimate the degree of their conservatism (Zell and Bernstein 2014). Against this background, this study measured those issues that divide citizens of the USA into conservatives and liberals (Jung et al. 2017a; PewResearchCenter 2014). In particular, we applied a paired comparison scaling (Jung et al. 2017a). Participants were exposed to eight pairwise statements about issues of business regulation, social welfare, racial discrimination, immigration, corporate profits, environmental laws, and homosexuality. Participants could choose between either a conservative or liberal statement. They could also refuse to answer. Responses were coded as conservative statement = 1; don’t know/refuse to answer = 0; liberal statement = − 1 and summed as recommended by Jung et al. (2017a). Thus, the larger the value of political ideology, the more conservatism is indicated. In contrast, the smaller the value of political ideology, the more liberalism is indicated.

Fair Trade Purchase Intention

We chose coffee as the fair trade product for this study as it is one of the most popular fair trade commodities on a global scale (FairtradeInternational 2018b; White et al. 2012). When developing a questionnaire to be administered online, researchers should avoid dull survey experiences due to purely text-based layouts (Malhotra et al. 2017). Therefore, participants were presented with a logo of fair trade coffee. Related to this logo, participants were asked to indicate how much they agree or disagree with four statements (e.g. ‘I would be likely to purchase this fair trade coffee’ and ‘I would be willing to buy this fair trade coffee’), which were adapted from White et al. (2012). The items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree).

Fair Trade Perspective-Taking

Davis (1980) developed a scale that reflects the ability or tendency of participants to adopt the point of view or perspective of other people. Davis’ (1980) scale measures the general ability of perspective-taking by the use of seven items (e.g. ‘Before criticizing somebody, I try to imagine how I would feel if I were in their place’ and ‘I believe that there are two sides to every question and try to look at them both’). Our aim was to investigate the specific ability to take the perspective of a farmer or worker in a developing country. To this end, we adapted all seven items (e.g. ‘Before criticizing fair trade, I try to imagine how I would feel if I were in the place of a farmer or worker in a developing country’ and ‘I believe that there are two sides to every question about fair trade and try to look at them both’). The items were measured using a Likert scale ranging from 0 (Does not describe me) to 4 (Describes me extremely well).

Fair Trade Identity

Fair trade identity was measured employing the scale developed by Chatzidakis et al. (2016). The three items of the scale (e.g. ‘To support fair trade is an important part of who I am’ and ‘I think of myself as someone who is concerned about ethical issues in consumption’) assess the self-identification of respondents with issues of fair trade (Chatzidakis et al. 2016). The items were measured based on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree).

Individual Characteristics

We asked participants to indicate their year of birth. Additionally, we asked them to indicate their income. To this end, participants were provided with income ranges (less than $10,000; $10,000–$19,999 etc.) and asked to choose their respective range. We preferred to ask for income ranges as we expected participants would not to be willing to divulge their exact income.

Control Variables

GenderFootnote 1 was used as a control variable. This is because conservatives could see women as mainly responsible for grocery shopping so that the purchase intention of conservative males could be lower than that of females. We also controlled for knowledge of fair trade as the fair trade concept may not be widely known in the USA. To this end, we used the scale of fair trade knowledge proposed by de Pelsmacker and Janssens (2007). The scale comprises three items (e.g. ‘Fair trade aims at creating better trade conditions for farmers and workers in developing countries’) that were measured using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree). Two further control variables were included in the survey. First, participants’ answers on fair trade purchase intention could be predicted by their past purchase behaviour. Therefore, we included the item ‘Did you buy fair trade coffee in the past?’ as covariate. Second, the local availability of fair trade coffee could affect a respondent’s intention to buy fair trade coffee. To control for availability, we included the item ‘How easy or difficult is it to find fair trade coffee where you live?’ as covariate.

Results

430 participants from the USA completed the survey (43.0% female, 57.0% male). There were four duplicate IP addresses in the dataset indicating that four participants did the survey twice. For each of these cases, the data of the second participation were excluded from the data. Moreover, participants were excluded from the data who used less than 90 s to complete the survey, which involved two cases. Furthermore, data of 12 participants were excluded from the data as they failed the attention check. Finally, multivariate outliers were identified with the probability of the Mahalanobis distance (Hair et al. 2018). Three of these probabilities were below 0.005 and thus excluded from the data. 409 valid responses were included in the statistical analysis.

In order to decide whether to use parametric or nonparametric methods for the statistical analysis, the distribution of data was investigated. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with Lilliefors correction is appropriate for testing data distribution. This test was, for instance, used to test for normality on fair trade purchase intention as the main dependent variable with a score of D(409) = .090, p < .01, which indicates a statistically significant deviation from normality. Statistically significant results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests for all six variables forming the model justified the use of SmartPLS Version 3.2.9 (Ringle et al. 2015), which does not require normally distributed data (Hair et al. 2017).

Analysis of the Measurement Model

We first checked the outer loadings. Hair et al. (2017) recommend to always eliminate indicators with loadings below 0.40. Two indicators of fair trade perspective-taking were thus deleted. Loadings between 0.40 and 0.70 should be removed from a scale if this leads to an increase in the average variance extracted (AVE) or to an increase in the composite reliability (CR) above the suggested threshold of 0.50 for AVE and of 0.60 for CR (Hair et al. 2017). Item 3 of the fair trade identity measure has a loading of 0.510. The AVE and CR values for the fair trade identity scale are above the threshold with item 3 (AVE = 0.604; CR = 0.813) as well as without item 3 (AVE = 0.800; CR = 0.889). Thus, there is no indication that justifies the removal of item 3 from the scale of fair trade identity. Finally, the AVE of all three constructs is above 0.50, which indicates their high convergent validity.

We examined the internal consistency reliability by use of Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, which are both interpreted in a similar way. Values below the threshold of 0.60 suggest insufficient internal consistency reliability, whereas values above 0.95 indicate redundancy of items (Hair et al. 2017). The values of all three constructs were within this range, thus indicating high internal consistency reliability.

Henseler et al. (2015) recommend assessing discriminant validity based on the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT), whereby values below 0.90, or below the more conservative threshold of 0.85, indicate discriminant validity (Henseler et al. 2015). All HTMT values of this study are below 0.85. Furthermore, discriminant validity is indicated if the HTMT bootstrap confidence interval does not contain the value one (Henseler et al. 2015). This study’s HTMT bootstrap confidence intervals for 10,000 replications do not include the value one. Moreover, all upper bounds of the HTMT bootstrap confidence intervals are below 0.85, which provides further evidence for discriminant validity.

Table 1 shows the results of the analysis of the measurement model. It demonstrates that the model has met all evaluation criteria, providing evidence for the reliability and validity of the measures.

Correlations

The means, standard deviations and correlations among the main constructs are provided in Table 2. Both fair trade perspective-taking and fair trade identity were significantly and negatively correlated with political ideology (\(r=-0.174\, {\text{a}}{\text{nd}}\,-0.303\text{, respectively,} \,p<0.01\)). Moreover, both fair trade perspective-taking and fair trade identity were significantly and positively correlated with fair trade purchase intention (\(r=0.511\, {\text{and}} \,0.554\,,\text{respectively}, \,p<0.01\)). These results justify the further analysis of the structural model. Finally, a moderation can be misleading when a predictor correlates with a moderator variable (Daryanto 2019). Political ideology neither correlates with birth year (\(r=-0.028\,\text{,} \,p=0.571\)) nor with income (\(r=0.026\,\text{,} \,p=0.599\)). On the basis of the latter two correlation results, there is no threat to the validity of the moderation test.

Analysis of the Structural Model

First, we checked the variance inflation factor (VIF) of the two predictor constructs so as to assess potential collinearity issues of the structural model. Specifically, we assessed PT as a predictor of IDEN (VIF value of 1.033) and INT (VIF value of 1.462) as well as IDEN as a predictor of INT (VIF value of 1.565) for collinearity. VIF values above 5 are critical (Hair et al. 2017). Here, all VIF values are below 5, indicating that collinearity is no issue. Therefore, we could proceed with the analysis of the results.

We then checked the R2 value of willingness to buy fair trade products as dependent variable. Based on the guidelines by Hair et al. (2011), the R2 value of INT (0.481) is moderate. Additionally, we evaluated the ƒ2 effect size. Based on Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, PT has a small effect size of 0.053 on INT, whereas IDEN has a medium effect size of 0.276 on INT. The latter result underlines the relative impact of IDEN on INT.

Next, we tested our hypotheses by inspecting the significance of the path coefficients and their bootstrap confidence intervals. To assess the significance of the relationships, we ran 10,000 bootstrap samples. The resulting values demonstrate a significant total effect, e.g. the sum of indirect and direct effects (Hair et al. 2017), of conservatism on fair trade purchase intention (\(b=-.143, p<0.001\)). When evaluating this effect size, one should keep in mind that conservatism is a composite score calculated by taking the sum of eight items as explained in the measurement section. Consequently, conservatism ranges from − 8 (participants always picked liberal statements) to 8 (participants always picked conservative statements).

The results also demonstrate a significant indirect effect of conservatism on fair trade purchase intention via fair trade perspective-taking, i.e. IDEO → PT → INT (\(b=-.033, p<0.05\)), supporting H1, as well as a significant specific indirect effect of conservatism on fair trade purchase intention via fair trade identity, i.e. IDEO → IDEN → INT (\(b=-.072, p<0.01\)), supporting H2.

Furthermore, we analysed the individual path coefficients in the model. All relationships in our model are statistically significant. The results show a significant effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking (\(b=-.162, p<0.01\)), which then significantly affects fair trade purchase intention (\(b=.200, p<0.001\)). The results further indicate a significant effect of conservatism on fair trade identity (\(b=-.152, p<0.01\)) as well as a significant effect of fair trade perspective-taking on fair trade identity (\(b=.511, p<0.001\)), supporting H3, which then significantly influences fair trade purchase intention (\(b=.474, p<0.001\)). With regard to the importance of the exogenous constructs for fair trade purchase intention, we found that fair trade identity is the main driver. Fair trade perspective-taking has less bearing on fair trade purchase intention than fair trade identity. Of the control variables, only past purchase behaviour had a significant and positive effect on fair trade purchase intention (\(b=.115, p<0.01\)).

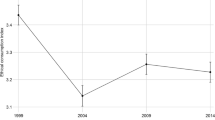

We also found a significant moderating effect of year of birth on the relationship between conservatism and fair trade perspective-taking (\(b=.110, p<0.05\)), in support of H4. This positive moderation effect means that the more positive the value of year of birth, the more positive is the effect of political ideology on fair trade perspective-taking. Simply put, the negative effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking is diminished by younger age. In the aforementioned relationship between conservatism and fair trade perspective-taking, income (\(b=-.121, p<0.01\)) is another significant moderator (H5). This negative moderation effect means that the more positive the value of income, the more negative is the effect of political ideology on fair trade perspective-taking. Simply put, the negative effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking is enhanced by higher income. All results of this study are shown in Table 3.

Discussion

The purpose of this research is to apply the theoretical lens of political conservatism to identify obstacles to the consumption of fair trade products. We found two of them.

First, the less developed capacity of conservatives to take the perspective of farmers or workers in LMIC decreases the intention to purchase fair trade coffee. Sparkman and Eidelman (2016) demonstrated the link between political ideology and ethnic perspective-taking. However, we are the first to demonstrate a relationship between conservatism and the specific ability to take the perspective of farmers or workers in LMIC. Moreover, we demonstrated a relationship between fair trade perspective-taking and the intention to purchase fair trade products. Thus, fair trade perspective-taking explains the influence of conservatism on fair trade purchase intention.

Perspective-taking is a strategy that allows individuals to navigate in environments between groups (Todd and Galinsky 2014). In our study, fair trade perspective-taking mirrors the ingroup orientation of conservatives. This inward-looking feature causes a decrease in the ability to take the perspective of outgroups by the conservative ingroup. The lower probability of conservatives to put themselves in the position of LMIC workers then relates to purchase intention, and thus the consumption sector can be understood as an ‘intergroup environment’ (Todd and Galinsky 2014, p. 374).

Second, the lower tendency of conservatives to make fair trade part of their identity causes a reduction in fair trade purchase intention. Bhattacharya and Elsbach (2002) showed that the identification of individuals with an organisation is related to experiences, whereas disidentification is based on values. In addition, action is taken only by the identifiers (Bhattacharya and Elsbach 2002). Our study demonstrates that disidentification is not only based on values but also on conservative beliefs. The present disidentification means that conservative beliefs signal to the self that the role of a fair trade customer is ideologically inappropriate. With such disidentification, a general political ideology is narrowed down to an individual level. Similar to Bhattacharya and Elsbach (2002), we found that only the identification with fair trade enhances action-taking intentions, i.e. the intention to buy fair trade products.

Moreover, both mediators between conservatism and purchase intention, i.e. fair trade perspective-taking and fair trade identity, are affiliated with each other in the sense that fair trade perspective-taking has a positive influence on fair trade identity. We consider both mediators to represent psychological hurdles for conservatives to the consumption of fair trade goods. The decreased ability of conservatives to step into the shoes of farmers in LMIC means that they tend to avoid the cognitive confrontation with the struggles of the poor in LMIC. Conservatism in HIC like the USA seems to be accompanied by the psychological narrowing of the external field of vision. The decreased fair trade identity, also arising from conservatism, means not being prepared to confront the self with issues of workers in LMIC. In other words, conservatism in HIC is associated with the psychological narrowing of the internal field of vision. Both fair trade perspective-taking and fair trade identity form a process of fading out the circumstances of an outgroup in need. To put it another way, fair trade perspective-taking and fair trade identity constitute a set of psychological blinkers that shield conservatives from the appeals of fair trade products.

Finally, we found age and income to moderate the effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking. Both mediators define the boundary conditions of the effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking, which is described next.

First, younger age reduces the negative effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking. In other words, the younger people are, the smaller is the effect of their conservatism on their ability to take the perspective of farmers or workers in LMIC. Cornelis et al. (2009) found that age increases social-cultural conservatism but not economic-hierarchical conservatism. In line with this, we argue that an increasing age intensifies the tendency of conservatives to favour their social-cultural ingroup. This then affects fair trade perspective-taking that requires the ability to adopt the viewpoint of people living in LMIC under circumstances that are socially and culturally very different from the circumstances in HIC.

Second, income maximises the negative effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking. The higher the income, the larger is the negative effect of conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking. Cognitive conservatism is facilitated by an orientation that aims at the prevention of losses and potential threats (Jost et al. 2003b). Moreover, conservatism relies on restraint or inhibition as tools for social regulation (Janoff-Bulman 2009). Given that, we argue that the higher the income of individuals, the greater are the potential losses and, thus, the more important is the necessity for individuals to regulate financial resources by restraint or inhibition rather than by activation (such as perspective-taking).

Managerial Implications

Marketing strategies of exporters in emerging markets succeed only when they take the contexts of the targeted developed markets into account (Samiee and Chirapanda 2019). However, firms in emerging markets often have limited resources, which can result in suboptimal marketing strategies (Samiee and Chirapanda 2019). Our managerial advice, including psychographic and demographic market segmentation in HIC, can be applied to boost the conservatives’ interests in fair trade consumption.

With regard to psychographic market segmentation, marketing strategies and communication tools of firms in LMIC or fair trade organisations should not require a high level of perspective-taking if targeting conservatives in HIC. Common fair trade advertising materials often picture scenes from LMIC, such as local farmers harvesting in the fields, or the advertisements use taglines that focus on poverty and inequality. In other words, common fair trade advertising materials represent the perspective of LMIC, which does not necessarily appeal to consumers of a conservative disposition. Fair trade advertisements that appeal to ingroups in HIC should avoid marketing messages based on perspective-taking if they are to appeal to consumers of a conservative disposition. Advertisements that display scenes of USA-ingroups, for example, a family in the USA having a fair trade breakfast, could move conservatives away from having to take the perspective of outgroups when reading the advertisement.

With regard to demographic market segmentation, marketing strategies of firms in LMIC or fair trade organisations targeting conservatives in HIC should focus on younger over older consumers as well as on consumers with lower over those with higher incomes. This would preclude up-market strategies aimed at older consumers. Our research results would rather suggest a marketing strategy that targets younger conservatives as well as conservatives with lower incomes as those groups of buyers seem to be less susceptible to the conservative belief system with regard to fair trade consumption. Not only can targeting younger conservatives and conservatives with lower incomes result in their greater inclination to buy fair trade products but also in their increased advocacy on behalf of fair trade within the general conservative market segment.

By applying approaches that make perspective-taking redundant and that aim at younger consumers with lower incomes, firms and fair trade initiatives can target the conservative consumer segment with a greater chance of success. This could eventually undermine the negative effects of conservatism on fair trade consumption as conservatism is driven by group dynamics. Additionally, the managerial advice to make perspective-taking redundant and to aim at younger consumers with lower incomes applies to similarly situated contexts where political conservatism inhibits certain consumer behaviours. This could involve sustainable consumption (Watkins et al. 2016), investments in energy-efficient technologies (Gromet et al. 2013), as well as vegetarian and vegan diets (Hodson and Earle 2018). However, our managerial advice is not applicable to cases in which political conservatism fosters certain consumer behaviours such as buying organic food (Martinez-de-Ibarreta and Valor 2018).

Limitations and Further Research

Our study focussed on ideological rather than on religious beliefs. However, 65% of the US Americans are Christians (PewResearchCenter 2019). Furthermore, Christian religiosity enhances positive views on socially responsible products (Graafland 2017). In particular, religious commitment increases the consumers’ willingness to pay for fair trade products when religion is salient in organisational contexts (Salvador et al. 2014). Because religiosity is associated with political conservatism (Malka et al. 2012), further research could investigate the interplay between religion, conservatism, and fair trade. Similar to the research findings of Peifer et al. (2016) on environmental consumption, religiosity could moderate the effect of the consumers’ political conservatism on their willingness to buy fair trade goods.

Moreover, we included four control variables in order to avoid ‘omitted variable bias’ (Wooldridge 2018, p. 84). However, adding control variables can result in ‘included variable bias, where adding control variables can bias coefficient estimates with respect to causal influence on the dependent variable’ (York 2018, p. 683). Therefore, we encourage further research that investigates the role of the covariates used here for the effect of political conservatism on fair trade purchase intention.

Finally, our research demonstrated a negative impact of political conservatism on fair trade consumption. Marketing communications could use framing by employing fair trade appeals that are anchored in and associated with political conservatism in order to better target consumers with a conservative disposition. For instance, Kidwell et al. (2013) revealed that appeals that are congruent with political ideologies increase sustainable behaviours. In particular, conservatives have increased intentions to undertake recycling when they read an advertisement with a binding appeal, whereas liberals have increased intentions to undertake recycling when they read an advertisement with an individualising appeal (Kidwell et al. 2013). Further research could identify and examine appeals that are in accordance with aspects of political conservatism that are relevant to fair trade consumption.

Conclusion

Our research introduced political ideology as an alternative and different lens when researching fair trade and associated consumer behaviour and decision making. We identified conservatism as a potential ideological obstacle to fair trade consumption. Furthermore, we demonstrated the psychological process that underlies the potential effect of conservatism on the consumption of fair trade products. Finally, our results suggest boundary conditions that regulate the impact of political conservatism on fair trade perspective-taking. The findings of the present study can have practical effects for fair trade initiatives as well as for agricultural firms in LMIC that want to sell fair trade products to additional customer segments in HIC or that want to increase their sales of fair trade products in such markets. It is important for fair trade initiatives and firms firstly, to release conservatives in HIC from the necessity of taking the perspective of farmers or workers in LMIC, and secondly to target younger conservatives with lower incomes.

Change history

02 March 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04780-w

Notes

We tried to put gender as a moderator variable in the relationship between political ideology and fair trade perspective-taking. The results did not show a significant effect of gender.

References

Andorfer, V., & Liebe, U. (2012). Research on fair trade consumption—A review. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(4), 415–435.

Bhattacharya, C., & Elsbach, K. (2002). Us versus them: The roles of organizational identification and disidentification in social marketing initiatives. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 21(1), 26–36.

Blader, S., Shirako, A., & Chen, Y. (2016). Looking out from the top: Differential effects of status and power on perspective taking. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(6), 723–737.

Burke, P., & Reitzes, D. (1981). The link between identity and role performance. Social Psychology Quarterly, 44(2), 83–92.

Charng, H., Piliavin, J., & Callero, P. (1988). Role identity and reasoned action in the prediction of repeated behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 51(4), 303–317.

Chatzidakis, A., Kastanakis, M., & Stathopoulou, A. (2016). Socio-cognitive determinants of consumers’ support for the fair trade movement. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(1), 95–109.

Clifford, S., Jewell, R., & Waggoner, P. (2015). Are samples drawn from Mechanical Turk valid for research on political ideology? Research & Politics, 2(4), 1–9.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lancaster/detail.action?docID=1192162. Accessed 12 July 2019.

Cornelis, I., Van Hiel, A., Roets, A., & Kossowska, M. (2009). Age differences in conservatism: Evidence on the mediating effects of personality and cognitive style. Journal of Personality, 77(1), 51–88.

Daryanto, A. (2019). Avoiding spurious moderation effects: An information-theoretic approach to moderation analysis. Journal of Business Research, 103, 110–118.

Davis, M. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 85–103.

Davis, M. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113–126.

De Pelsmacker, P., & Janssens, W. (2007). A model for fair trade buying behaviour: The role of perceived quantity and quality of information and of product-specific attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(4), 361–380.

EcoviaIntelligence. (2019). The global market for organic food & drink: Trends & future outlook. Retrieved October 25, 2019, from https://www.ecoviaint.com/global-organic-food-market-trends-outlook/.

FairtradeFoundation. (2019). What is Fairtrade? Retrieved from https://www.fairtrade.org.uk/What-is-Fairtrade. Accessed 26 Oct 2019.

FairtradeInternational. (2011). Fair Trade Glossary – A joint publication of the World Fair Trade Organization, Fairtrade International and FLO-CERT. Accessed 12 Nov 2018.

FairtradeInternational. (2018a). Retail sales value of Fairtrade International from 2004 to 2017 worldwide (in million U.S. dollars). Retrieved December 1, 2018, from Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/806183/fair-trade-international-global-sales/. Accessed 31 Jan 2019.

FairtradeInternational. (2018b). Working together for fair and sustainable trade: Annual report 2017–2018. Retrieved from https://www.fairtrade.net/fileadmin/user_upload/content/2009/about_us/annual_reports/2017-18_FI_AnnualReport.pdf. Accessed 31 Jan 2019.

Feather, N. (1979). Value correlates of conservatism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(9), 1617–1630.

Fernandes, D., & Mandel, N. (2014). Political conservatism and variety-seeking. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24(1), 79–86.

Galinsky, A., Magee, J., Inesi, M., & Gruenfeld, D. (2006). Power and perspectives not taken. Psychological Science, 17(12), 1068–1074.

Graafland, J. (2017). Religiosity, attitude, and the demand for socially responsible products. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(1), 121–138.

Gromet, D., Kunreuther, H., & Larrick, R. (2013). Political ideology affects energy-efficiency attitudes and choices. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(23), 9314–9319.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2018). Multivariate data analysis. Andover: Cengage Learning.

Hair, J., Hult, G., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

Hair, J., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135.

HKExnews. (2018). Global retail market size from 2011 to 2021 (in billion U.S. dollars). Retrieved December 1, 2018, from Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/914324/global-retail-market-size/.

Hodson, G., & Earle, M. (2018). Conservatism predicts lapses from vegetarian/vegan diets to meat consumption (through lower social justice concerns and social support). Appetite, 120, 75–81.

Janoff-Bulman, R. (2009). To provide or protect: Motivational bases of political liberalism and conservatism. Psychological Inquiry, 20(2–3), 120–128.

Josiassen, A. (2011). Consumer disidentification and its effects on domestic product purchases: An empirical investigation in the Netherlands. Journal of Marketing, 75(2), 124–140.

Jost, J. (2006). The end of the end of ideology. American Psychologist, 61(7), 651–670.

Jost, J. (2015). Resistance to change: A social psychological perspective. Social Research, 82(3), 607–636.

Jost, J. (2017). The marketplace of ideology: “Elective affinities” in political psychology and their implications for consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(4), 502–520.

Jost, J., Blount, S., Pfeffer, J., & Hunyady, G. (2003a). Fair market ideology: Its cognitive-motivational underpinnings. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, 53–91.

Jost, J., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A., & Sulloway, F. (2003b). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 339–375.

Jost, J., Napier, J., Thorisdottir, H., Gosling, S., Palfai, T., & Ostafin, B. (2007). Are needs to manage uncertainty and threat associated with political conservatism or ideological extremity? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(7), 989–1007.

Jung, J., & Mittal, V. (2020). Political identity and the consumer journey: A research review. Journal of Retailing, 96(1), 55–73.

Jung, K., Garbarino, E., Briley, D., & Wynhausen, J. (2017a). Blue and red voices: Effects of political ideology on consumers’ complaining and disputing behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(3), 477–499.

Jung, K., Garbarino, E., Briley, D., & Wynhausen, J. (2017b). Political ideology and consumer research beyond complaining behavior: A response to the commentaries. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(3), 511–518.

Kaikati, A., Torelli, C., Winterich, K., & Rodas, M. (2017). Conforming conservatives: How salient social identities can increase donations. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(4), 422–434.

Khan, R., Misra, K., & Singh, V. (2013). Ideology and brand consumption. Psychological Science, 24(3), 326–333.

Kidwell, B., Farmer, A., & Hardesty, D. (2013). Getting liberals and conservatives to go green: Political ideology and congruent appeals. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(2), 350–367.

Kim, J., Park, B., & Dubois, D. (2018). How consumers’ political ideology and status-maintenance goals interact to shape their desire for luxury goods. Journal of Marketing, 82(6), 132–149.

Lewin, K. (1952). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers. London: Tavistock Publications.

Malhotra, N., Nunan, D., & Birks, D. (2017). Marketing research: An applied approach (5th ed.). Harlow: Pearson.

Malka, A., Lelkes, Y., Srivastava, S., Cohen, A., & Miller, D. (2012). The association of religiosity and political conservatism: The role of political engagement. Political Psychology, 33(2), 275–299.

Martinez-de-Ibarreta, C., & Valor, C. (2018). Neighbourhood influences on organic buying. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(5), 513–521.

Mead, G. (1934/1972). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist (C. Morris Ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Ordabayeva, N., & Fernandes, D. (2018). Better or different? How political ideology shapes preferences for differentiation in the social hierarchy. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(2), 227–250.

Peifer, J., Khalsa, S., & Ecklund, E. (2016). Political conservatism, religion, and environmental consumption in the United States. Environmental Politics, 25(4), 661–689.

PewResearchCenter. (2012). The American-Western European values gap. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2011/11/17/the-american-western-european-values-gap/. Accessed 23 Sep 2019.

PewResearchCenter. (2014). Political polarization in the American Public. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/. Accessed 20 Aug 2020.

PewResearchCenter. (2019). In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace. https://www.pewforum.org/2019/10/17/in-u-s-decline-of-christianity-continues-at-rapid-pace/. Accessed 23 Aug 2020.

Phau, I., Teah, M., Chuah, J., & Liang, J. (2017). Consumer’s willingness to pay more for luxury fashion apparel made in sweatshops. In T. Choi & B. Shen (Eds.), Luxury fashion retail management (pp. 71–88). Singapore: Springer.

Ray, J. (1985). What old people believe: Age, sex, and conservatism. Political Psychology, 6(3), 525–528.

Ringle, C M., Wende, S, & Becker, J-M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. Retrieved from http://www.smartpls.com

Salvador, R., Merchant, A., & Alexander, E. (2014). Faith and fair trade: The moderating role of contextual religious salience. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(3), 353–371.

Samiee, S., & Chirapanda, S. (2019). International marketing strategy in emerging-market exporting firms. Journal of International Marketing, 27(1), 20–37.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sparkman, D., & Eidelman, S. (2016). “Putting myself in their shoes”: Ethnic perspective taking explains liberal-conservative differences in prejudice and stereotyping. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 1–5.

Staricco, J. (2016). Fair trade and the fetishization of levinasian ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 138(1), 1–16.

Stryker, S., & Burke, P. (2000). The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(4), 284–297.

Tarrant, M., Calitri, R., & Weston, D. (2012). Social identification structures the effects of perspective taking. Psychological Science, 23(9), 973–978.

Todd, A., & Galinsky, A. (2014). Perspective-taking as a strategy for improving intergroup relations: Evidence, mechanisms, and qualifications. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8(7), 374–387.

Truett, K. (1993). Age differences in conservatism. Personality and Individual Differences, 14(3), 405–411.

Van Loo, E., Caputo, V., Nayga, R., Seo, H., Zhang, B., & Verbeke, W. (2015). Sustainability labels on coffee: Consumer preferences, willingness-to-pay and visual attention to attributes. Ecological Economics, 118, 215–225.

Vlaeminck, P., Vandoren, J., & Vranken, L. (2016). Consumers’ willingness to pay for fair trade chocolate. In M. Squicciarini & J. Swinnen (Eds.), The economics of chocolate (pp. 180–191). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Watkins, L., Aitken, R., & Mather, D. (2016). Conscientious consumers: A relationship between moral foundations, political orientation and sustainable consumption. Journal of Cleaner Production, 134(Part A), 137–146.

Wempe, J. (2005). Ethical entrepreneurship and fair trade. Journal of Business Ethics, 60(3), 211–220.

White, K., MacDonnell, R., & Ellard, J. (2012). Belief in a just world: Consumer intentions and behaviors toward ethical products. Journal of Marketing, 76(1), 103–118.

Winterich, K., Zhang, Y., & Mittal, V. (2012). How political identity and charity positioning increase donations: Insights from Moral Foundations Theory. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(4), 346–354.

Wolter, J., Brach, S., Cronin, J., & Bonn, M. (2016). Symbolic drivers of consumer-brand identification and disidentification. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 785–793.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2018). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach (7th ed.). Boston: Cengage.

York, R. (2018). Control variables and causal inference: A question of balance. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21(6), 675–684.

Zell, E., & Bernstein, M. (2014). You may think you’re right … Young adults are more liberal than they realize. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(3), 326–333.

Funding

Thomas Usslepp has received financial support by the Fulgoni Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that they have no potential conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This project was approved by the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences and Lancaster Management School Research Ethics Committee (Ethics ID: FL18108).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.

About this article

Cite this article

Usslepp, T., Awanis, S., Hogg, M. et al. The Inhibitory Effect of Political Conservatism on Consumption: The Case of Fair Trade. J Bus Ethics 176, 519–531 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04689-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04689-w