Men (people) are rarely aware of the real reasons which motivate their actions.

—Edward L. Bernays, Propaganda, 1928

Abstract

Drawing from cognitive learning theories we hypothesize that exposure to nationalistic appeals that suggest consumers should shun foreign brands for moral reasons increases the general belief in consumers that buying foreign brands is morally wrong. In parallel, drawing from the theory of psychological reactance we posit that such appeals may, against their communication goal, increase the reputation of foreign luxury brands. We term the juxtaposition of these apparently contradictory effects the “Ambivalence Hypothesis.” Further, drawing from prior research on source-similarity effects we posit that foreign luxury brands that communicate cultural proximity to target consumers (i.e., a local brand positioning) reinforce psychological reactance (“Clean Conscience Hypothesis”). We test these hypotheses experimentally in the context of luxury car brand advertising in China, a market that is heavily dominated by foreign brands, and therefore provides a breeding ground for ambivalent consumer reactions. Results show that exposure to nationalistic appeals enhances consumers’ national identity dispositions (patriotism, local identity), which results in higher levels of consumer ethnocentrism. Further, nationalistic appeals enhance the social responsibility associations that consumers hold for foreign luxury brands and their countries of origin, which results in a higher brand reputation. Finally, effects of nationalistic appeals on foreign luxury brand reputation are positively stronger for brands using a local vs. a foreign or a global positioning. These findings suggest that nationalistic appeals are a double-edged sword with important implications for ethics in political communication and luxury brand marketing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world today is marked by a rise of neo-nationalist movements, such as US President Trump’s idea to “Make America Great Again,” or Britain’s decision to leave the EU. Related discourses in the media seek to strengthen people’s national identity by emphasizing the ethical and moral obligations that citizens have toward their nations. For instance, US President Trump has labeled critics of his politics as unpatriotic and immoral (Gabriel 2018). Similarly, China’s President Xi Jinping recently argued on state television that Chinese people should “… tell every Chinese person that patriotism is one’s duty, is an obligation” (Reuters 2019). Such nationalistic appeals may nurture the general belief in consumers that buying foreign brands is the morally wrong course of action. For example, a recent survey found that Chinese consumers are stating that, out of patriotism, they intend to avoid buying American brands, opting instead for Chinese ones (Moon 2019). However, it is equally conceivable that the same nationalistic appeals may trigger reactions in people that run opposite to those very discourses (cf., Jung 2018; Xuecun 2014). For example, a series of articles published in 2013 in China’s state-run newspaper People’s Daily attempted to defame the iconic US brand Apple using headlines such as “Smash Apple’s ‘Incomparable’ Arrogance.” This campaign against Apple backfired with consumers and led to other media outlets naming the most arrogant Chinese state-run companies, including the People’s Daily itself (Greenfield 2013). The latter example resonates with research suggesting that nationalistic appeals in the media may induce reactance in an audience, thus increasing resistance against, rather than support of, nationalism (Krämer 2014; Muller et al. 2017).

The present study offers new insights into how exposure to nationalistic appeals suggesting that consumers should shun foreign brands for moral reasons affect consumer behavior in relation to foreign luxury brands. First, we contend that such nationalistic appeals elicit ambivalent reactions in consumers. On the one hand side, drawing from theories on cognitive learning and belief assimilation (Cacioppo and Petty 1989; Stang 1975; Zajonc 1968) we hypothesize that nationalistic appeals enhance consumers’ national identity dispositions (patriotism and local identity), thus reinforcing their general belief that buying foreign brands is morally wrong (i.e., consumer ethnocentrism). On the other hand side, drawing from Brehm’s (1966) theory of psychological reactance we posit that the same nationalistic appeals may, against their communication goal, increase the social responsibility associations that consumers hold for foreign brands and their countries, thus resulting in a higher reputation of those brands. We term the juxtaposition of these apparently contradictory effects the “Ambivalence Hypothesis.” It suggests a psychological conflict in consumers about what is morally or ethically wrong vs. acceptable when considering foreign brands. Second, drawing from research on source-similarity effects (e.g., Faraji-Rad et al. 2015; Gino et al. 2009; Jiang et al. 2010) we argue that foreign brands that display closeness to a local culture by employing a local brand positioning (Alden et al. 1999) legitimize positive thoughts or attitudes about those brands. Hence, we advance what we term the “Clean Conscience Hypothesis,” which posits that psychological reactance effects caused by nationalistic appeals (i.e., enhanced foreign brand reputation) are greater for foreign brands using a local vs. a foreign or a global positioning strategy.

We test these hypotheses in the context of luxury car brand advertising in China, one of the world’s largest and fastest-growing luxury markets (MarketWatch 2019; Yap 2018). It is estimated that in 2020 there will be roughly 23 million Chinese households with a monthly disposable income of more than $34,000 and the luxury car market in particular will benefit from this development (Busch 2019). The Chinese luxury car market is heavily dominated by foreign brands with three European giants alone (Audi, Mercedes Benz and BMW) controlling about 70 percent of that market. As of 2019 no Chinese luxury car brand belonged to the top selling ones (Demandt 2019). This context provides a breeding ground for consumer reactance in response to nationalistic appeals, given that foreign luxury car brands are in China the most widespread and most popular alternatives available. Therefore, this setting is particularly suitable for testing our ambivalence hypothesis and we find robust empirical support for it.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. First, we provide an overview of studies on nationalism and consumers’ national identity dispositions, as well as a review of the literature on social responsibility associations and brand reputation. Then, we develop a conceptual model alongside a set of theoretically derived hypotheses. Next, we describe our experimental study and report its empirical results. Finally, we discuss the theoretical and practical implications of our findings for ethics in political communication and luxury brand marketing, as well as their limitations alongside propositions for future research.

Conceptual Background

Nationalism and Nationalistic Appeals

Nationalism, the individual belief in national superiority and an orientation toward national dominance (Kosterman and Feshbach 1989), has experienced a resurgence in recent years and became a major concern in public debates and policy discussions around the world (Bieber 2018). There is an abundant academic literature devoted to gaining a better understanding of the nature and antecedents of nationalism, as well as to how people respond to nationalistic appeals. Nationalistic appeals are “efforts to appeal to preexisting nationalist sentiment and to deliberate attempts to stir up nationalist sentiment” (Downs and Saunders 1999, p. 119). We briefly review research from three key areas of interest to the present study, namely political communication, brand advertising, and ethics.

First, in the field of political communication, authors have studied how nationalistic appeals relate to voter turnout and electoral success. For instance, Block and Negrine (2017) explore how the success of populist politicians such as Nigel Farage in the UK or Hugo Chávez in Venezuela is supported by appeals to “basic nationalistic feelings of ordinary people.” Such appeals may be classified as propaganda, i.e., communication that attempts to manipulate and manage collective attitudes (Lasswell 1927), as shown by Bos and Brants (2014) in the context of the Dutch populist Geert Wilders, or Richardson and Colombo (2013) in the context of the Lega Nord in Italy. Second, in the area of advertising, authors have studied how nationalistic appeals embedded in brand communication affect brand preferences. For instance, following the events on “9/11”, numerous US brands such as Chrysler or General Motors used advertising that expressed compassion for victims and supported patriotism (Kinnick 2003; McMellon and Long 2006). Such advertising not only served to enhance consumer trust in national US brands, but also instilled the idea into people’s minds that it is one’s fundamental moral and civic duty to engage in consumerism and support American brands in particular (Tsai 2010). Subsequent research showed that associating brands with national symbols or patriotic themes can activate consumers’ feelings of national identity and, therefore, increase their tendency to prefer home-country brands (e.g., Carvalho and Luna 2014; Yoo and Lee 2016). Third, researchers in the area of ethics are concerned with how nationalism and nationalistic appeals tie together with moral and ethics. For instance, Bergman et al. (2017) suggest that current neo-nationalistic trends may be an expression of peoples’ dissatisfaction with the dissociation between corporate and societal interests. This contrast between the public and the business interest has led to growing research in what is termed political CSR, i.e., activities where CSR has political impact (Fooks et al. 2013; Morsing and Roepstorff 2015). There is also an established stream of ethics research concerned with epistemic disorders of the propaganda processes, suggesting that nationalistic appeals are not ethically neutral (Cunningham 1993). Nationalistic propaganda may be unethical for at least two reasons. First, the possession of power (by propagandists) does not mean it is right for them to use it (the “is–ought problem”). Second, by supplanting the search for truth with imposed an truth, propaganda destroys the basis for mutual thoughtful interpersonal communication and thus the essential ingredients of an ethical existence (cf., Black 2001).

National Identity

One way of studying the relationships that people have with the world around them is the social identity approach. Social identity is “that part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to the membership” (Tajfel 1978, p. 63). Social identity may take various forms such as religious- or political identity, but of particular relevance to the present study is the construct of national identity, which is the extent to which people identify with a certain culture or nation and favor its unique characteristics over those of other cultures or nations (Keillor and Hult 1999). National identity is an ever-present umbrella concept (Hanson and O’Dwyer 2019; Keillor and Hult 1999) for which authors have identified a wide range of neighboring constructs (see Papadopoulos et al. 2018 for an overview). These include, among others, topophilia (the affective bond one holds with places, e.g., Tuan 1990), racism (the discrimination of people of a different race or ethnicity, e.g., Ouellet 2007), or animosity (feelings of antipathy against another country, e.g., Klein et al. 1998). The present study focuses on consumers’ national identity dispositions in terms of patriotism, local identity, and consumer ethnocentrism. These dispositions are widely recognized for reflecting in-group favoritism in relation to domestic brands and out-group biases against foreign brands (e.g., Balabanis and Diamantopoulos 2016; Balabanis et al. 2001; Zeugner-Roth et al. 2015; Zhang and Khare 2009). Patriotism or national pride is the degree of devoted love, attachment, and loyalty that one feels in relation to the home-country, and is associated with support for conservative and right-wing political parties (Kosterman and Feshbach 1989). Patriotism determines a readiness to sacrifice for the home-country and acts as a defense mechanism for the in-group (Druckman 1994). Local identity refers to feelings of belongingness to a local social community and identification with its lifestyle. It reflects peoples’ faith in and respect for local traditions, history and customs, as well as their interest in local events and activities (Lantz and Loeb 1998). Finally, consumer ethnocentrism (CET) is the beliefs held by consumers “about the appropriateness, indeed morality, of purchasing foreign-made products” (Shimp and Sharma 1987, p. 280). To ethnocentric consumers, purchasing foreign or imported products is morally wrong because, in their minds, it hurts the domestic economy, causes loss of jobs, and is plainly unpatriotic (Shimp and Sharma 1987; Winit et al. 2014).

Social Responsibility Associations

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) refers to the obligation of firms to fulfill economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities (Carroll 1979). This entails the expectation of consumers that firms must act consistently with what the society considers morally or ethically acceptable. Arguably, exposure to nationalistic appeals that suggest consumers should shun foreign brands for moral reasons will impact how consumers perceive the social responsibility of those brands and their countries of origin.

CSR associations broadly reflect consumers’ perceptions of a brand’s status and activities with respect to its societal obligations (Brown and Dacin 1997; Zerbini 2017). Positive CSR associations are a source of competitive advantage and critically affect overall brand reputation as perceived by consumers (Brown and Dacin 1997; Sen et al. 2006). Maignan (2001) developed measures to assess CSR associations based on Carrol’s (1979) four CSR dimensions. In the present study we do not differentiate CSR dimensions, but only consider consolidated- or higher-order CSR associations (e.g., Berens et al. 2005; Sen et al. 2006; Wagner et al. 2009). Dimitrova et al. (2017) emphasize the importance of considering social responsibility not only in relation to brands (CSR), but also in relation to countries. Similarly, Dekhili and Achabou (2015) show that a country’s ecological image affects consumer evaluations of eco-labeled products. We therefore posit that exposure to nationalistic appeals may not only affect consumers’ CSR associations, but also their beliefs about the social responsibility of the country from which foreign brands originate. For example, consumers may hold social responsibility associations not only for Mercedes Benz as a brand, but also for the country from which Mercedes Benz originates, Germany. Drawing from established research on CSR associations (e.g., Berens et al. 2005; Brown and Dacin 1997; Sen et al. 2006; Wagner et al. 2009), we consider country-of-origin social responsibility (COOSR) associations to reflect consumers’ perceptions of a country’s status and activities with respect to its societal obligations. Both types of social responsibility associations, CSR and COOSR, should inform consumers’ overall brand reputation (cf., Brown and Dacin 1997; Lee et al. 2019; Wagner et al. 2009).

Theory Development

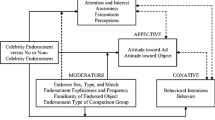

Our main contention is that exposure to nationalistic appeals may elicit contradictory or ambivalent reactions in consumers, a phenomenon that we term the “Ambivalence Hypothesis” (H1a, b). Figure 1 illustrates this idea as two juxtaposed layers of competing psychological effects. In layer 1, which focuses on cognitive learning and belief assimilation, we expect nationalistic appeals to enhance consumers’ national identity dispositions (patriotism, local identity) and ultimately CET (H1a). In layer 2, which focuses on psychological reactance, we expect nationalistic appeals to enhance consumers’ social responsibility associations in relation to foreign brands (CSR) and their countries of origin (COOSR), and ultimately foreign brand reputation (H1b). For both layers we posit mediational chains of effects between the considered construct (H2a, b). A corollary of the Ambivalence Hypothesis (H1a, b) is that we expect nationalistic appeals to moderate the well-established negative effect of CET on foreign brand reputation (H3). Moreover, although not illustrated in Fig. 1, our second main contention is what we term the “Clean Conscience Hypothesis,” which posits that psychological reactance caused by exposure to nationalistic appeals is contingent on foreign brand positioning (H4).

Main effects (“Ambivalence Hypothesis”)

Layer 1 (assimilation) Owing to assimilation effects, it is well known that information that people process can activate knowledge structures such as traits in them (Bargh et al. 1996). A widely accepted truism about how political propaganda works is that the more frequently people are exposed to an idea, the more they are likely to accept it (Cacioppo and Petty 1989). Classical learning theories such as Zajonc’s (1968) “mere-exposure” effect or Stang’s (1975) “learning-leads-to-liking hypothesis” support this basic psychological mechanism. Accordingly, associating brands with national symbols or patriotic themes can activate individuals’ feelings of national identity and increase their tendency to refuse foreign brands (e.g., Nijssen and Douglas 2004). We therefore expect that exposure to nationalistic appeals (vs. no exposure) will enhance consumers’ national identity dispositions (patriotism and local identity), as well as their general belief that purchasing foreign brands is morally wrong (CET).

H1a

Exposure to nationalistic appeals enhances consumers’ national identity dispositions (patriotism and local identity) and CET.

Layer 2 (reactance) Brehm’s (1966, 1981) theory of psychological reactance is concerned with how people behave when they feel their freedom of choice being threatened. Generally, when people face restrictions in the choices that they can make, they tend to consider the restricted option as more attractive (e.g., Brehm 1989; Brock and Mazzocco 2004; Verhallen 1982). A striking demonstration of the reactance phenomenon is the statutory ban of phosphates in laundry detergents for environmental reasons in Miami, Florida, in the 1970s (Mazis et al. 1973). Although it was clear that phosphates have no functional impact on cleaning effectiveness, stores outside of the city boundaries reported significant increases in the sales of detergents containing phosphate shortly after the ban came into effect. Studies have delivered ample evidence of reactance reactions in various fields. For example, warning messages that aim to reduce binge drinking may incite people to drink more (Dillard and Shen 2005), messages that aim to prevent drug use may incite people to try or use drugs (Burgoon et al. 2002), warning messages against tobacco consumption may incite people to smoke (Grandpre et al. 2003), or nationalistic appeals may increase resistance against rather than support of nationalism (Hameleers et al. 2017; Krämer 2014; Muller et al. 2017).

Following the reactance paradigm, it is conceivable that nationalistic appeals that suggest consumers should shun foreign brands for moral reasons may, against their communication goal, elicit positive consumer dispositions toward those brands. We therefore expect that exposure to nationalistic appeals (vs. no exposure) will enhance CSR- and COOSR associations in relation to foreign brands, as well as foreign brand reputation.

H1b

Exposure to nationalistic appeals enhances consumers’ social responsibility associations in relation to foreign brands (CSR) and their countries of origin (COOSR), as well as foreign brand reputation.

Mediating Effects

Layer 1 More general or situationally invariant individual dispositions should causally precede dispositions that are less general and more situationally variant (cf., Alden et al. 2006). Accordingly, researchers widely agree that dispositional CET results from more general national identity dispositions such as patriotism, local identity, nationalism, or internationalism (Balabanis et al. 2001; Sharma et al. 1995). For example, Balabanis and Diamantopoulos (2016, p. 58) state that “foreign and domestic product purchase behavior largely depends on consumer predispositions.” Hence, in combination with H1a, we expect a mediational chain of effects between exposure to nationalistic appeals and CET via patriotism and local identity.

H2a

Patriotism and local identity mediate the relationship between exposure to nationalistic appeals (vs. no exposure) and dispositional CET.

Layer 2 Cognitive consistency theories (e.g., Festinger 1957) suggest that people strive for harmony in their beliefs and seek to avoid dissonances. Hence, when consumers associate social responsibility with a brand (CSR) or a country (COOSR), they tend to develop belief-consistent feelings that increase their perceptions of overall brand reputation. Accordingly, a wealth of research considers that what consumers know about a brand (e.g., CSR associations) informs their overall brand reputation (Brown and Dacin 1997; Lee et al. 2019; Maignan 2001; Salmones et al. 2005; Sen et al. 2006; Wagner et al. 2009). Hence, in combination with H1b, we expect a mediational chain of effects between exposure to nationalistic appeals and brand reputation via CSR- and COOSR associations.

H2b

Consumers’ social responsibility associations in relation to foreign brands (CSR) and their countries of origin (COOSR) mediate the effect of exposure (vs. no exposure) to nationalistic appeals on brand reputation.

Effects of CET on brand reputation

Highly ethnocentric consumers believe that purchasing foreign brands is morally wrong, threatens the domestic industry and causes unemployment (Shankarmahesh 2006; Shimp and Sharma 1987; Verlegh 2007; Winit et al. 2014). Therefore, CET should be negatively associated with foreign brand reputation. Further, since exposure to nationalistic appeals may not only enhance CET (H1a) but also elicit enhanced foreign brand reputation in line with the reactance paradigm (H1b), it is conceivable that exposure to nationalistic appeals moderates the effect of CET on foreign brand reputation. In particular, we expect for the condition without exposure to nationalistic appeals a negative effect of CET on reputation. However, as a corollary of our preceding set of hypotheses we expect for the condition with exposure to nationalistic appeals that the negative effect of CET on reputation turns positive.

H3

Exposure to nationalistic appeals moderates the relationship between CET and foreign brand reputation so that it is negative in the no appeal condition but positive in the appeal condition.

Contingency (“Clean Conscience Hypothesis”)

What people think and how they behave depends in many ways on what their social environment considers acceptable (Cialdini et al. 1990). Thus, socially objectionable or unacceptable behaviors may promote psychological conflicts between “heard and mind,” (e.g., one’s individual preferences compared to what the social norm determines as acceptable) that people strive to resolve (Shiv and Fedorikhin 2002). Exposure to nationalistic appeals may create such a conflict in consumers, as such appeals likely increase the salience of the idea that appreciating foreign brands is objectionable or socially undesirable. This psychological conflict may be pronounced in China, a collectivistic society, where great importance is placed on social conformity (e.g., Markus and Kitayama 1991).

Alden et al. (1999) suggested that global marketers should consider one of three brand positioning strategies: A local brand positioning associates the brand with local cultural meanings, a foreign brand positioning links the brand to a specific foreign culture, and a global brand positioning identifies the brand with globally shared meanings. Significant prior research has demonstrated a positive effect of source similarity (i.e., the degree to which a message source or an adviser and a recipient are alike) on persuasion (e.g., Gino et al. 2009; Jiang et al. 2010). One explanation for the source-similarity effect relevant to the present study is that higher similarity induces feelings of certainty in recipients, which validates the message or the advice received as a decision input and increases persuasion (Faraji-Rad et al. 2015). That is, consumers may misattribute positive feelings of certainty induced by source similarity to their brand evaluations (cf., Schwarz 2011), suggesting that a foreign brand’s closeness to the consumer’s own culture (i.e., a local brand positioning) legitimizes positive thoughts or attitudes about the foreign brand. We term this expectation the “Clean Conscience Hypothesis.” Thus, we expect brand positioning to moderate reactance effects caused by nationalistic appeals (H1b), so that the increased brand reputation resulting from exposure to nationalistic appeals will be higher when the foreign brand adopts a local positioning compared to a foreign or a global positioning.

H4

The positive effect of exposure (vs. no exposure) to nationalistic appeals on the reputation of foreign luxury brands is stronger for brands that adopt a local positioning than for brands that adopt a global or a foreign positioning.

Methodology

Experimental Design

The experimental design was a 3 (exposure to a nationalistic pride or a CET appeal, no exposure) × 3 (brand positioning: local, foreign, global) between-subjects design. We used the two types of nationalistic appeals (described below) as a replication factor for a more robust test of our hypotheses. First, each respondent was randomly assigned to one of the two experimental (exposure to a nationalistic pride or CET appeal) or the control (no exposure) condition. We then measured the generic dispositional constructs in layer 1 of our conceptual model (i.e., patriotism, local identity, and CET). Subsequently, respondents were randomly assigned to one of the three brand positioning conditions (local vs. foreign vs. global positioning, described below), and within these three conditions they were again randomly assigned to one out of six foreign luxury car brands (described below). We then measured the brand specific constructs in layer 2 of our conceptual model (i.e., CSR- and COOSR associations and brand reputation).

Stimuli and Manipulation Checks

Nationalistic Appeals

Stimuli We presented participants in the experimental “exposure to nationalistic appeal” condition with a mock webpage reminiscent of Quora.com, a social media platform that allows users to ask questions to the community, which are then answered and discussed by members of the community. The stimuli were written in Mandarin and graphically designed to emulate real posts made by Quora community membersFootnote 1. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two posts that we framed either as a nationalistic pride appeal, or a nationalistic CET appeal. We expected both types of nationalistic appeals to affect out-group biases against foreign brands (Balabanis et al. 2001; Zeugner-Roth et al. 2015). The pride appeal began with the following heading “Chinese Pride: Why are you proud of China?” followed by an answer text presented as provided by a Quora user. That answer elaborated on historical, cultural, and economic achievements of China, as well as the pride of being Chinese and buying Chinese products. Similarly, the CET appeal began with the heading “China First: Why we should protect China?” followed by an answer text that elaborated more explicitly on the importance of protecting the Chinese economy and the moral duty that Chinese have to buy domestic instead of foreign products. We asked participants to read the post, and take a few minutes to think about it. Participants in the control condition were not exposed to any webpage.

Manipulation Check We pretested the stimuli qualitatively with six Chinese graduate students. In one-to-one interviews with one of the researchers, the participants were asked to read the stimuli and talk about the feelings and thoughts that they elicited in them. Participants believed that both appeals had been taken from real social media discussions. Moreover, all participants broadly noted that both appeals elicited feelings of belongingness to China and patriotism, and that the stimuli reminded them of the moral duties that Chinese people have towards China, its people and its economy. We then asked participants to classify each appeal as either one that predominantly aims at raising a general sense of national pride (i.e., the pride appeal), or at inciting people to prefer Chinese over foreign brands (i.e., the CET appeal). All participants classified the two types of nationalistic appeals correctly, in support of the appropriateness of our experimental stimuli.

Brand Positioning

Stimuli We exposed each participant to one mock ad for a foreign luxury car brand employing either a local, a foreign or a global brand positioning. The ads were written in Mandarin and depicted altogether six popular luxury car brands that are currently available in China and that originate from six different countries (Germany: Mercedes Benz; Italy: Maserati; Japan: Lexus; Sweden: Volvo; UK: Land Rover; USA: Cadillac) (Sha et al. 2013). Hence, we created 18 mock ads in total (3 positioning strategies × 6 foreign brands). All ads showed similar types of luxury cars (i.e., second-tier luxury cars) with similar colors (i.e., dark gray or black). The brand positioning manipulations varied in regard to the ethnicity of the spokesperson, the copy text, and the pictorial illustrations. For example, ads employing a local brand positioning displayed a typical Chinese spokesperson together with a picture of the Great Wall of China and a copy text highlighting the popularity of the brand in China. Global brand positioning ads displayed people from various cultural backgrounds (oriental, occidental and African) as spokespersons together with a picture of the globe and a copy text highlighting the popularity of the brand worldwide. Finally, foreign brand positioning ads used images of foreign people representative of the geographic origin of the brand in question (e.g., occidental for Germany or the US) together with typical symbols of the specific country of brand origin in question (e.g., the Brandenburg gate for Germany or the statue of liberty for the USA) and a copy text highlighting the popularity of the brand in its country of origin. Moreover, all ads stated the brand’s country of origin (see footnote 1).

Manipulation Check We used a convenience sample of 28 Chinese graduate students to ensure the efficacy of the mock ads. We presented the students with operational definitions of Alden et al.’s (1999) three positioning strategies and provided pertinent examples for each. We then asked them to state if each of the 18 mock ads (six countries of brand origin × three positioning strategies) reflected either a local, a global, or a foreign brand positioning strategy and to identify each brand’s country of origin. Respondents correctly classified 97% of the ads with a local brand positioning, 92% of the ads with a foreign brand positioning, and 94% of the ads with a global brand positioning, thus confirming the effectiveness of the brand positioning manipulations. Moreover, all respondents correctly identified each brand’s country of origin for all mock ads.

Data Collection Procedures

We collected data in 2018 from N = 554 prospective Chinese luxury car buyers living in China. Focusing on prospective luxury car buyers is warranted because part of the success of luxury brand marketing is actually reflected in the ability that the brand has to generate positive attitudes beyond its actual consumer base, as such attitudes help harness the value of scarcity (a key element of luxury marketing, see for example Bian and Forsythe 2012; Kemp 1998) and contribute to building the dream value of the luxury brand (Kapferer 2015; Kapferer and Valette-Florence 2016).

Chinese research assistants distributed the online questionnaire to Chinese non-student participants that they approached through popular social media platforms such as RenRen or WeChat. They also recruited participants they knew personally (family, friends, co-workers), and whom they encouraged to recruit further participants (Salganik and Heckathorn 2004). We established the suitability of respondents as prospective luxury car buyers ex ante and ex post. Ex ante, we explained on the welcome page to the online survey that questions were targeted at people interested in luxury cars and encouraged those without such interest not to continue with it. Ex post, we confirmed the suitability of our respondents as such targets by contrasting their demographic profile with that of luxury car owners in China, as described below.

We took various measures to ensure high data quality. First, the questionnaire contained a standard attention check (“To show me your attention, please select ‘strongly agree’”) (Kees et al. 2017). A total of N = 48 participants failed to answer the attention check correctly and their responses were eliminated. Second, we asked participants in the priming conditions (pride- or CET appeal) to indicate how interesting they found the social media discussion (not interesting at all; moderately interesting; very interesting). A total of N = 117 participants who found the discussion not- or only moderately interesting were excluded from the subsequent analyses based on Krosnick’s (1991) theory of satisficing in survey responses. Following this theory, less interested participants increase attrition, produce attenuated effects, and generate findings of limited generalizability (cf., Krosnick 1991; Oppenheimer et al. 2009). The final usable sample therefore consisted of N = 389 participants. This sample is broadly reflective of the typical luxury car owner in China in terms of age, gender and education (Daily 2017; Du 2016), as 87% of the respondents are 25 years or older, 43.2% are female, and 87.9% are University educated.

We measured the constructs of interest using established scales (see Appendix 1). Layer 1 We used six items to measure consumer patriotism (Kosterman and Feshbach 1989), four items to measure Chinese local identity (Tu et al. 2012; Zhang and Khare 2009), and four items to measure CET (Sharma 2014). Layer 2 Three items from Wagner et al. (2009) served to measure CSR associations that consumers hold for a brand, and we adapted that same measure of CSR associations to measure social responsibility associations in relation to a brand’s country-of-origin (COOSR) (five items). We confirmed the face validity of the COOSR scale by consulting with four fellow researchers, who concurred that different facets of the construct that our items tap into provide a reasonably good reflection of the conceptual scope of what one may associate with the social responsibility associations that people have with a country. Finally, we used four items to measure overall brand reputation (Homer 1995; Wagner et al. 2009). We developed the questionnaire in English and translated it into Mandarin using the collaborative iterative translation method (Douglas and Craig 2007). The scale to measure Chinese local identity (Tu et al. 2012; Zhang and Khare 2009) was readily available in Mandarin. We used seven-point rating scales throughout.

Results

We first examined the psychometric qualities of the employed measures. An exploratory factor analysis with a six-factor oblique rotation (PROMAX) showed that most items loaded strongly (λ > 0.7) and significantlyFootnote 2 on their target factor with weak cross-loadings on the other factors. Only one (reverse coded) item from the brand reputation scale loaded weakly on its target factor and lowered the internal consistency of that scale considerably. We removed this item from the subsequent analyses (see Appendix 1). We then built composite scores of the constructs by averaging item scores. Table 1 displays descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for scale reliabilities, as well as well as bi-variate correlations between the various constructs. Results show that conceptually similar constructs that measure patriotism, local identity and CET (layer 1) are strongly positively correlated with each other, and conceptually similar constructs that measure CSR, COOSR and brand reputation (layer 2) are strongly positively correlated with each other. Moreover, constructs from layer 1 are not or only weakly correlated with constructs from layer 2.

Test of H1a, b (“Ambivalence Hypothesis”)

The tests of the H1a, b rely on ANOVA assessments with the various constructs from layer 1 and layer 2 as the dependent variables, and the experimental exposure to nationalistic appeals (no exposure, pride appeal, CET appeal) as factors. The treatment cell means appear in Table 2.

Results show that exposure to the pride appeal (vs. no appeal) leads to significantly enhanced patriotism (MNo appeal = 6.14 vs. MPride appeal = 6.65, F(1, 290) = 13.95, p < 0.01), slightly enhanced local identity (MNo appeal = 5.46 vs. MPride appeal = 5.68; F(1, 290) = 2.37, p < 0.10), and significantly enhanced dispositional CET (MNo appeal = 2.97 vs. MPride appeal = 3.57, F(1, 290) = 7.19, p < 0.01). Similarly, exposure to the CET appeal (vs. no appeal) leads to significantly enhanced patriotism (MNo appeal = 6.14 vs. MCET appeal = 6.43, F(1, 292) = 3.94, p < 0.05), significantly enhanced local identity (MNo appeal = 5.46 vs. MCET appeal = 5.86, F(1, 292) = 8.29, p < 0.01), and significantly enhanced dispositional CET (MNo appeal = 2.97 vs. MCET appeal = 4.31, F(1, 292) = 40.48, p < 0.01). Overall, these results lend support to H1a.

We also find that exposure to the pride appeal (vs. no appeal) leads to slightly enhanced CSR associations (MNo appeal = 4.08 vs. MPride appeal = 4.29, F(1, 290) = 2.32, p < 0.10), significantly enhanced COOSR associations (MNo appeal = 4.26 vs. MPride appeal = 4.85, F(1, 290) = 12.91, p < 0.01), as well as to a significantly higher brand reputation (MNo appeal = 4.78 vs. MPride appeal = 5.31, F(1, 290) = 11.31, p < 0.01). Similarly, exposure to the CET appeal (vs. no appeal) leads to a significant increase of CSR associations (MNo appeal = 4.08 vs. MCET appeal = 4.77, F(1, 292) = 23.11, p < 0.01), significantly enhanced COOSR associations (MNo appeal = 4.26 vs. MCET appeal = 4.87, F(1, 292) = 14.12, p < 0.01), as well as to significantly higher brand reputation (CET appeal: MNo appeal = 4.78 vs. MCET appeal = 5.36, F(1, 292) = 12.2, p < 0.01). Overall, these results lend support to H1b.

In combination, these results broadly support the “Ambivalence Hypothesis,” which predicted, on the one hand (layer 1), that exposure to nationalistic appeals would lead to enhanced national identity dispositions and CET (H1a) and, on the other hand (layer 2), that exposure to nationalistic appeals would lead to higher social responsibility associations in relation to foreign brands as well as higher brand reputation (H1b).

Test of H2a, b (Mediations)

We used Hayes’ (2012) PROCESS tool (model 4) with 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals and 1,000 resamples to test the proposed mediation hypotheses.

The previously reported results show that exposure (vs. no exposure) to nationalistic appeals positively impacts all dependent variables and that the proposed mediators are positively related to the dependent variables in the model. The empirical conditions for mediation to occur are therefore fulfilled. We created dummy variables for each of the manipulations (i.e., one for exposure to the pride appeal vs. no exposure; and one for the exposure to the CET appeal vs. no exposure) and used them separately as independent variables in PROCESS to replicate the tests of our mediation hypotheses on both layers of our conceptual model.

Regarding layer 1 (H2a), we find consistently positive indirect effects of exposure (vs. no exposure) to nationalistic appeals on dispositional CET for both types of nationalistic appeals and for both mediators (patriotism, local identity). In particular, for the pride appeal the results (Table 3) show a significant indirect effect via patriotism (B = 0.150; p < 0.05), and a positive but non-significant indirect effect via local identity (B = 0.072; p > 0.05). This suggests that the pride appeal affects CET mainly by enhancing people’s feelings of patriotism and to a lesser extent by enhancing their local identity. Moreover, for the CET appeal we find significant indirect effects via both patriotism (B = 0.068; p < 0.05) and local identity (B = 0.091; p < 0.05). Hence, H2a is broadly supported by the data.

Regarding layer 2 (H2b), we find consistently positive indirect effects of exposure (vs. no exposure) to nationalistic appeals on foreign brand reputation for both types of nationalistic appeals and for both mediators (CSR and COOSR associations). Results for the pride appeal (Table 4) show non-significant indirect effect via CSR associations (B = 0.093; p > 0.05) and a significant positive indirect effect via COOSR associations (B = 0.109; p < 0.05). Such differing findings suggest that the pride appeal affects foreign brand reputation by enhancing the social responsibility associations that people hold for foreign countries (COOSR) but not by enhancing the social responsibility associations that they hold for foreign brands (CSR). We discuss these differential effects in the conclusions section. Moreover, for the CET appeal we find strong and significant indirect effects via CSR associations (B = 0.397; p < 0.05) as well as via COOSR associations (B = 0.127; p < 0.05). Overall, the data broadly support H2b.

Test of H3 (Effect of CET on Brand Reputation)

We used Hayes’ (2012) PROCESS tool (model 1) with dispositional CET as the independent variable and brand reputation as the dependent variable to test H3. The previously created dummy variables for each of the manipulations served as moderators and allowed us to replicate the test of this hypothesis for both types of nationalistic appeals. The results show, as expected, a significant negative effect of dispositional CET on brand reputation (B = − 0.103; p < 0.05) for the condition without exposure to nationalistic appeals. However, the effect of dispositional CET on brand reputation becomes positively significant for both conditions with exposure to nationalistic appeals, for both the pride appeal (B = 0.155; p < 0.05) and the CET appeal (B = 0.140; p < 0.1). Moreover, the effect differences of dispositional CET on brand reputation are statistically significant for both, the no exposure vs. the exposure to the pride appeal conditions (B = 0.258; p < 0.05), as well as for the no exposure vs. the exposure to the CET appeal conditions (B = 0.243; p < 0.05). Hence, H3 is supported by the data.

Test of H4 (“Clean Conscience Hypothesis”)

The test of H4 relies again on ANOVA assessments with brand reputation as the dependent variable and the experimental exposure to nationalistic appeals, as well as the experimental brand positioning manipulations (local, global, foreign), as factors. With H4 we expected reactance reactions caused by nationalistic appeals to be contingent on brand positioning, such that the positive effect of nationalistic appeals on brand reputation would be stronger for brands with a local positioning than for brands with a global or a foreign positioning.

The ANOVA results show a marginally significant interaction effect of the pride appeal (vs. no appeal) with the three positioning strategies on brand reputation (F(2, 286) = 2.40, p < 0.1). The comparison of the mean difference scores (Table 2) shows that the effect of the pride appeal on brand reputation is positively stronger for brands with a local positioning (MPride appeal − MNo appeal: 5.76 − 4.75 = 1.01) than for brands with a global positioning (MPride appeal − MNo appeal: 5.01 − 4.76 = 0.25). The difference between these two effects is statistically significant (z = 2.00; p < 0.05). Similarly, the effect of the pride appeal on brand reputation is positively stronger for brands with a local positioning (MPride appeal − MNo appeal: 5.76 − 4.75 = 1.01) than for brands with a foreign positioning (MPride appeal − MNo appeal: 5.17 − 4.83 = 0.34). The difference between these effects is statistically significant (z = 1.71; p < 0.05; one-tailed test). Moreover, the results for the pride appeal show that brand reputation is higher for brands with a local positioning than for brands with a global positioning (M = 5.76 vs. M = 5.01; p < 0.05) and higher for brands with a local positioning than for brands with a foreign positioning (M = 5.76 vs. M = 5.17; p < 0.05; one-tailed test). Likewise, results show a marginally significant interaction effect of the CET appeal (vs. no appeal) with the three positioning strategies on brand reputation (F(2, 288) = 2.70, p < 0.1). The comparison of the mean difference scores shows that the effect of the CET appeal on reputation is positively stronger for brands with a local positioning (MCET appeal − MNo appeal: 5.85 − 4.75 = 1.10) than for brands with a global positioning (MCET appeal − MNo appeal: 4.96 − 4.76 = 0.20), and the difference between these effects is statistically significant (z = 2.39; p < 0.01). Similarly, the effect of CET appeal on reputation is positively stronger for brands with a local positioning (MCET appeal − MNo appeal: 5.85 − 4.75 = 1.10) than for brands with a foreign positioning (MCET appeal − MNo appeal: 5.25 − 4.83 = 0.42), and difference between these effects is again significant (z = 1.51; p < 0.1; one-tailed test). Finally, the results for the CET appeal show that brand reputation is higher for brands with a local positioning than for brands with a global positioning (M = 5.85 vs. M = 4.96; p < 0.01) and higher for brands with a local positioning than for brands with a foreign positioning (M = 5.85 vs. M = 5.25; p < 0.1, one-tailed test).

In summary, the combined results clearly support the “Clean Conscience Hypothesis” (H4). Brand positioning strategies alter the effects of our nationalistic pride and CET appeals on luxury car brand reputation. While both types of nationalistic appeals promote a higher brand reputation, the effect is particularly pronounced for brands with a local positioning. This is in line with our proposition that a local brand positioning may help people solve the moral conflict arising from increased positive perceptions of foreign brands following reactance reactions.

Discussion and Conclusion

Theoretical Contributions and Implications

Consumer research only rarely considers ambivalence in people’s reactions despite many counterintuitive findings reported in attitudinal research studies in apparent support of it. Examples are studies showing that higher levels of consumer ethnocentrism enhance the belief in global citizenship (Strizhakova et al. 2008) as well as those showing that ego-focused emotional appeals elicit more favorable evaluations from collectivist consumers (Aaker and Williams 1998). Recent research into hypocrisy, i.e., the idea that a person’s deeds do not align with her words (cf., Batson et al. 2006; Gillani et al. 2019; Wagner et al. 2009) suggests that there may often be some parallel conflicting thought processes that people negotiate and that guide their judgments.

The present research studies how, in the context of luxury car brand advertising in China, exposure to nationalistic appeals provokes psychological conflicts in Chinese consumers. Such conflicts arise as appeals suggest that consumers should shun foreign brands for moral reasons. We find that exposure to nationalistic appeals can significantly enhance consumers’ national identity dispositions (local identity and patriotism) and ultimately increase the general belief in them that buying foreign brands is morally or ethically wrong (i.e., consumer ethnocentrism). On the other hand, we also find that exposure to such appeals promotes enhanced social responsibility associations that consumers hold for foreign luxury car brands (CSR), those brands’ countries of origin (COOSR), and ultimately increase the perceived reputation of those brands. We termed the juxtaposition of these apparently contradictory effects the “Ambivalence Hypothesis” and supported it theoretically based on theories on cognitive learning and belief assimilation (Cacioppo and Petty 1989; Stang 1975; Zajonc 1968) on the one side, and the theory of psychological reactance (Brehm 1966) on the other. A major theoretical contribution of the present study therefore relates to the conceptualization of ambivalent or conflicting cognitive processes behind consumer evaluations of foreign luxury brands.

Our findings on ambivalent reactions also raise questions about the ethicality of nationalistic appeals. Indeed, the ambivalent reactions that we find in our study suggest that appeals to people’s nationalism as a moral duty may curtail people’s freedom of choice or freedom of will, a major psychological underpinning of the reactance paradigm (Brehm and Brehm 1981; Grandpre et al. 2003). The ethics literature notes two main concerns related to freedom of choice, namely whether such freedom is a necessary condition for moral responsibility, and whether, and to what degree, freedom of choice is valuable at all (Enflo 2012). The current neo-nationalistic tendencies and related nationalistic discourses may thus be ethically questionable in that they depict nationalism and consumer ethnocentrism as the morally correct course of action. However, such a stance promotes nationalism merely as an affective phenomenon, hence a manifestation of emotion and perhaps atavistic drives, rather than as the consequence of rational deliberation (cf., Freeden 1998; Weinstock 1996). It is therefore not surprising that moral circumcisions of people’s freedom trigger backlash among consumers.

Our study also supports the “Clean Conscience Hypothesis,” which posited that reactance to nationalistic appeals may create a psychological conflict between “heart and mind” in Chinese consumers (cf., Shiv and Fedorikhin 2002). Drawing from prior research on source similarity (e.g., Faraji-Rad et al. 2015; Gino et al. 2009; Jiang et al. 2010), we conjectured that a foreign luxury brand’s closeness to the local consumers’ culture (i.e., a local brand positioning) would induce feelings of certainty in consumers that they may misattribute to their evaluations of that brand. In particular, we hypothesized that a local brand positioning (compared to a foreign or a global positioning) would be more likely to legitimize the holding of positive thoughts about the foreign brand, therefore enhancing the reactance reaction.

Furthermore, our research expands the boundaries of reactance theory into the realm of nationalistic appeals in relation to consumers’ sustainability perceptions of luxury brands. In doing so, our findings add to research on reactance toward warning messages about binge drinking (Dillard and Shen 2005), drug use (Burgoon et al. 2002) or tobacco consumption (Grandpre et al. 2003). Extant research has mostly considered reactance as potentially harming, rather than supporting, the effect of public policies geared toward ethical or sustainable behavior. For instance, studies have considered how policies devised to encourage social responsibility in relation to transport (Tertoolen et al. 1998) or conservation of environmental resources (Clayton et al. 2013) might not elicit the intended positive effect, as consumers perceive social responsibility messages as curtailing their behavioral freedom. Instead, in this study we find that reactance reactions can support consumer perceptions of the social responsibility of brands. In particular, we find that reactance toward nationalistic appeals increases, rather than reduces, consumer perceptions of social responsibility in relation to foreign luxury brands.

Finally, we also find that reactance reactions leading to increased foreign luxury brand reputation are related to the enhanced social responsibility associations that people hold for brands (i.e., CSR associations) as well for the countries from which those brands originate (i.e., COOSR associations). This finding emphasizes the importance of considering social responsibility associations as explanatory variables of brand reputation (Wagner et al. 2009; Berens et al. 2005). Further, our study also shows differential effects related to two types of social responsibility associations considered (i.e., CSR and COOSR). In particular, while exposure to the pride appeal elicits reactance only at the country level (COOSR), the CET appeal elicits reactance at both the brand level (CSR) and the country level (COOSR). These differential effects add to the robustness of our findings, as they align with the idea that pride and CET appeals share the common basis of an in-group bias. In the case of the national pride appeal the bias is generic in nature while the CET appeal incorporates an additional consumption-focus (related to firm and brand perceptions) (cf., Balabanis et al. 2001; Shimp and Sharma 1987).

Practical Implications

Populist communication and nationalistic appeals are highly relevant today given a generic increase in nationalism across the world and especially because many popular media outlets such as Fox News in the USA (Hutton 2020) or the Global Times in China (Yuan 2020) tend to support a nationalistic worldview. Against that backdrop, our findings have significant implications for governments, media editors, and luxury brand marketers.

Our findings show that governments and media editors intent on raising nationalistic views via moralizing discourses with their people and audiences may fail. They may do so because appeals to a moral duty will, on the one hand, increase general preference for domestic over foreign goods while, on the other hand, eliciting reactance reactions in form of increased perceptions of foreign luxury brands, thus questioning their sensibleness. These findings are in line with research on populistic media communication and campaigns. Campaigns of populist candidates are more negative and contain more character attacks and more fear messages than campaigns of non-populist candidates (Nai 2018) and research shows that such messages also increase resistance against, rather than support of, populism (Krämer 2014; Muller et al. 2017). Thus, our findings suggest that the nationalistic appeals popular with governments such as those of Brazil or India (Harris et al. 2020) may deliver their intended effects only on the surface.

Our findings also have significant implications for luxury brand marketers. On the one hand, our findings suggest that foreign luxury brands operating in markets characterized by nationalism and where nationalistic appeals are prevalent in the media may not experience a loss in brand equity owing to the reactance reactions that we identified. Further, our findings suggest that foreign luxury brand marketers may even be able to benefit from nationalistic appeals as such appeals amplify positive effects of a local brand positioning on brand reputation. Moreover, our study confirms the important role that social responsibility associations play in shaping the reputation of foreign luxury brands. Specifically, our findings suggest that luxury brands can increase their reputation by building their social responsibility credentials in two ways: first, by cultivating CSR associations, for example through appropriate CSR initiatives; second, by highlighting their countries of origin when those countries demonstrate social responsibility in the eyes of consumers. For instance, by highlighting Germany as its country of origin, Mercedes Benz could improve perceptions of brand reputation in consumers because of the social responsibility credentials that the country, rather than the brand itself, has. These findings may explain the consequences of the Chinese powdered milk scandal of 2008. Back then, milk tainted with a toxic compound caused several deaths and thousands of ill infants in China (Jourdan 2013). The backlash arising from that scandal seriously harmed not only the reputation of dairy giant Shijiazhuang Sanlu Group, but also of other food producers originating from China (Bandurski 2008). The reputational damage persists, as even a decade later Chinese consumers still trust foreign powdered milk brands more than domestic ones, thus emphasizing that social responsibility associations do not only matter in relation to brands (CSR) but also in relation to the countries from which brands originate (COOSR). Overall, our findings on the importance of social responsibility associations in luxury branding support the view of Laurent Claquin, president of Kering Americas (the owner of luxury brands such as Gucci, Yves Saint Laurent, and Balenciaga), that “Sustainability is a necessity, not an option” for luxury brands (Lein 2018). We therefore advise luxury marketers to nurture and reinforce social responsibility associations in the mind of consumers.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has limitations that point at interesting avenues for future research. First, we acknowledge that our study is based on data from prospective rather than actual luxury car buyers. Although we believe that our approach is warranted for the present study, which focuses on brand attitudes rather than purchase behavior, we suggest that future research should examine effects of nationalistic appeals on luxury car purchasing intentions, price acceptance, or real choice behavior using data from confirmed luxury car buyers.

Second, our focus on one single product category (luxury cars) and one single context (China) limits the external validity of our conclusions and calls for more research in different settings and with different types of products. For instance, consumer reactance to nationalistic appeals may be less pronounced for lower-involvement products (e.g., accessories or beauty products) than for higher-involvement products (e.g., luxury cars or watches). Similarly, as our focal brands can be considered to represent the second-tier segment of the market for luxury cars, future research should extend our work into high-end or first-tier luxury car brands such as Lamborghini, Ferrari or Aston Martin.

Third, the effect of nationalistic appeals may vary depending on whether people belong to majority vs. minority cultural groups as well as depending on their religious beliefs, as those different groups may take different views on the government issuing those appeals. We are unable to test for these possibilities, as we did not gather data on these variables, so future research should explore them.

Fourth, we measured reactance in a context, luxury car consumption in China, where consumers have no or only limited access to local products in that category. Thus, we cannot rule out that the lack of availability of domestic brand alternatives may have enhanced reactance reactions to nationalistic appeals. Nationalistic appeals may be less likely to promote reactance when domestic brands are widely available because such domestic alternatives would reduce the impact of the appeals on consumers’ freedom of choice for a luxury brand. Future research should therefore test our “Ambivalence Hypothesis” in different settings to establish its boundary conditions.

Fifth, our study follows the literature in viewing reduced freedom of choice as the theoretical explanation for reactance reactions (Brehm and Brehm 1981; Grandpre et al. 2003). However, it is conceivable that the role that threatened freedom plays in reactance reactions may vary depending on individuals’ collectivistic versus individualistic orientations, as research suggests that reactance reactions may vary by cultural orientation (Graupmann et al. 2012). Similarly, effects of nationalistic appeals may be contingent on an individual’s ethical ideology or ethical beliefs position, as people with a higher ethical stance, i.e., idealism and/or utilitarianism (Forsyth 1980), may be more likely to feel that nationalistic appeals infringe their individual freedoms.

Sixth, future research should test the impact of COOSR associations on consumer perceptions of brand reputation in other countries as well as employ a structured scale development approach (Churchill 1979) to further the development of a potentially more comprehensive multi-dimensional scale to measure social responsibility associations that people have with countries.

Finally, future research should deepen our understanding of the differential effects that we find for different types of nationalistic appeals (national pride vs. CET appeals) on brand reputation by considering other types of nationalistic appeals, such as appeals to boycott specific foreign companies as well as appeals to xenophobia (Harun and Shah 2013) or animosity (Klein et al. 1998). Such appeals are topical, as reflected by the recent consideration of the US government to ban Huawei from 5G networks in the USA (Sanger et al. 2019).

Appendix 1: Measures

Construct/Items | Source |

|---|---|

Patriotism I love my country I am proud to be a Chinese I am emotionally attached to China My commitment to China always is strong I feel a great pride in China When I see the Chinese flag flying I feel great | Kosterman and Feshbach (1989) |

Local Identity I care about knowing local events My heart mostly belongs to my local community I respect my local traditions I identify that I am a local citizen | Tu et al. (2012) |

Consumer Ethnocentrism We should purchase products manufactured in China instead of letting other countries get rich off of us A real Chinese should always buy China-made products It is not right to purchase foreign products, because it puts Chinese out of jobs Chinese should not buy foreign products, because this hurts China’s businesses and causes unemployment | Sharma (2014) |

Corporate Social Responsibility Associations I think this company … … is a socially responsible company … is concerned to improve the well-being of our society … follows high ethical standards | Wagner et al. (2009) |

Country of Origin Social Responsibility** I think that [country] … … is an environmentally and socially very responsible country … aims to improve people’s well-being … is characterized by high ethical standards … is very respectful of ethical principles … has a government that ensures sustainable development | New measure |

Brand Reputation In general, my feelings toward this brand are … … unfavorable/favorable … bad/good … unpleasant/pleasant … positive/negative* |

Notes

Stimuli are available on request.

Following Hair et al.’s (2006, p. 128) guidelines for identifying significant factor loadings, factor loadings of .6 and above are considered significant (p < .05) with a sample of N = 85 or more subjects.

References

Aaker, J. L., & Williams, P. (1998). Empathy versus pride: The influence of emotional appeals across cultures. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(3), 241–261.

Alden, D. L., Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., & Batra, R. (1999). Brand positioning through advertising in Asia, North America, and Europe: The role of global consumer culture. Journal of Marketing, 63(1), 75–87.

Alden, D. L., Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., & Batra, R. (2006). Consumer attitudes toward marketplace globalization: Structure, antecedents and consequences. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 23(3), 227–239.

Balabanis, G., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2016). Consumer xenocentrism as determinant of foreign product preference: A system justification perspective. Journal of International Marketing, 24(3), 58–77.

Balabanis, G., Diamantopoulos, A., Mueller, R. D., & Melewar, T. (2001). The impact of nationalism, patriotism and internationalism on consumer ethnocentric tendencies. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(1), 157–175.

Bandurski, D. (2008). Press controls feed China's food problem. Retrieved Mar 15, 2019 from https://web.archive.org.

Bargh, J. A., Chen, M., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 230–244.

Batson, C. D., Collins, E., & Powell, A. A. (2006). Doing business after the fall: The virtue of moral hypocrisy. Journal of Business Ethics, 66(4), 321–335.

Berens, G., van Riel, C. B. M., & van Bruggen, G. H. (2005). Corporate associations and consumer product responses: The moderating role of corporate brand dominance. Journal of Marketing, 69(3), 35–48.

Bergman, M., Bergman, Z., & Berger, L. (2017). An empirical exploration, typology, and definition of corporate sustainability. Sustainability, 9(5), 1–13.

Bian, Q., & Forsythe, S. (2012). Purchase intention for luxury brands: A cross cultural comparison. Journal of Business Research, 65(10), 1443–1451.

Bieber, F. (2018). Ethnopolitics. Ethnopopulism and the Global Dynamics of Nationalist Mobilization, 17(5), 558–562.

Black, J. (2001). Semantics and ethics of propaganda. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 16(2–3), 121–137.

Block, E., & Negrine, R. (2017). The populist communication style: Toward a critical framework. International Journal of Communication, 11, 178–197.

Bos, L., & Brants, K. (2014). Populist rhetoric in politics and media: A longitudinal study of the Netherlands. European Journal of Communication, 29(6), 703–719.

Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Oxford, UK: Academic Press.

Brehm, J. W. (1989). Psychological reactance: Theory and applications. In T. K. Srull (Ed.), NA - Advances in consumer research (Vol. 16, pp. 72–75). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Brehm, S. S., & Brehm, J. W. (1981). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control. New York: Academic Press.

Brock, T. C., & Mazzocco, P. J. (2004). Responses to scarcity: A commodity theory perspective on reactance and rumination. In R. A. Wright, J. Greenberg, & S. S. Brehm (Eds.), Motivational analyses of social behavior: Building on Jack Brehm’s contributions to psychology (pp. 129–148). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68–84.

Burgoon, M., Alvaro, E., Grandpre, J., & Voulodakis, M. (2002). Revisiting the theory of psychological reactance. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Busch, J. (2019). Chinese luxury car market continues to grow. Retreived Dec 19, 2019 https://www.china-certification.com.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1989). Effects of message repetition on argument processing, recall, and persuasion. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 10(1), 3–12.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Carvalho, S. W., & Luna, D. (2014). Effects of national identity salience on responses to ads. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 1026–1034.

Churchill, G. A. J. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015–1026.

Clayton, S., Litchfield, C., & Geller, E. S. (2013). Psychological science, conservation, and environmental sustainability. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 11(7), 377–382.

Cunningham, S. B. (1993). Sorting out the Ethics of Propaganda. Communication Studies, 3, 233–245.

Daily, J. (2017). Why Chinese women buy more luxury cars than the global average. Retrieved Mar 15, 2019 from https://www.scmp.com.

Dekhili, S., & Achabou, M. A. (2015). The influence of the country-of-origin ecological image on ecolabelled product evaluation: An experimental approach to the case of the European ecolabel. Journal of Business Ethics, 131(1), 89–106.

Demandt, B. (2019). China car sales analysis 2018: Brands. Retrieved Aug 24, 2019 from https://carsalesbase.com.

Dillard, J. P., & Shen, L. (2005). On the nature of reactance and its role in persuasive health communication. Communication Monographs, 72(2), 144–168.

Dimitrova, B. V., Kim, S., Bell, M., & Frantz, N. (2017). Global country social responsibility: What is it? An abstract. In N. Krey & P. Rossi (Eds.), Academy of marketing science annual conference (pp. 17–18). Cham: Springer.

Douglas, S. P., & Craig, C. S. (2007). Collaborative and iterative translation: An alternative approach to back translation. Journal of International Marketing, 15(1), 30–43.

Downs, E. S., & Saunders, P. C. (1999). Legitimacy and the limits of nationalism: China and the Diaoyu Islands. International Security, 23(3), 114–146.

Druckman, D. (1994). Nationalism, patriotism, and group loyalty: A social psychological perspective. Mershon International Studies Review, 38(1), 43–68.

Du, X. (2016). Chinese consumers go for hi-tech premium cars, says hurun report. Retrieved Mar 15, 2019 from https://www.chinadaily.com.cn.

Enflo, K. (2012). Measures of freedom of choice. Doctoral Thesis, Uppsala University,

Faraji-Rad, A., Samuelsen, B. M., & Warlop, L. (2015). On the Persuasiveness of similar others: The role of mentalizing and the feeling of certainty. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(3), 458–471.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Fooks, G., Gilmore, A., Collin, J., Holden, C., & Lee, K. (2013). The limits of corporate social responsibility: Techniques of neutralization, stakeholder management and political CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(2), 283–299.

Forsyth, D. R. (1980). A taxonomy of ethical ideologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(1), 175.

Freeden, M. (1998). Is nationalism a distinct ideology? Political Studies, 46(4), 748–765.

Gabriel, T. (2018). Two visions of patriotism clash in the midterm elections. Retrieved Aug 15, 2019 from https://www.nytimes.com.

Gillani, A., Kutaula, S., Leonidou, L. C., & Christodoulides, P. (2019). The impact of proximity on consumer fair trade engagement and purchasing behavior: The moderating role of empathic concern and hypocrisy. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04278-6.

Gino, F., Shang, J., & Croson, R. (2009). The impact of information from similar or different advisors on judgment. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(2), 287–302.

Grandpre, J., Alvaro, E. M., Burgoon, M., Miller, C. H., & Hall, J. R. (2003). Adolescent Reactance and Anti-Smoking Campaigns: A Theoretical Approach. Health Communication, 15(3), 349–366.

Graupmann, V., Jonas, E., Meier, E., Hawelka, S., & Aichhorn, M. (2012). Reactance, the self, and its group: When threats to freedom come from the ingroup versus the outgroup. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(2), 164–173.

Greenfield, R. (2013). China's apple smear campaign has totally backfired. Retrieved Mar 15, 2019 from https://www.theatlantic.com.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis, 6edn. Upper Saddele River, NJ: Pearson.

Hameleers, M., Bos, L., & de Vreese, C. H. (2017). "They did it": The effects of emotionalized blame attribution in populist communication. Communication Research, 44(6), 870–900.

Hanson, K., & O’Dwyer, E. (2019). Patriotism and nationalism, left and right: Aq-methodology study of American National Identity. Political Psychology, 40(4), 777–795.

Harris, B., Stott, M., & Kazmin, A. (2020). Jair Bolsonaro finds unlikely ally in Hindu Nationalist Modi. Retrieved Jan 25, 2019 from https://www.ft.com.

Harun, H., & Shah, K. A. M. (2013). Xenophobia and Its effects on foreign products purchase: A proposed conceptual framework. International Journal of Business, Economics and Law, 3(1), 88–94.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). Process: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. https://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

Homer, P. M. (1995). Ad size as an indicator of perceived advertising costs and effort: The effects on memory and perceptions. Journal of Advertising, 24(4), 1–12.

Hutton, W. (2020). The Bbc is a pillar of civilisation. No wonder populists want to destroy it. Retrieved Jan 26, 2019 from https://www.theguardian.com.

Jiang, L., Hoegg, J., Dahl, D. W., & Chattopadhyay, A. (2010). The persuasive role of incidental similarity on attitudes and purchase intentions in a sales context. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(5), 778–791.

Jourdan, A. (2013). China threatens heavier fines after milk powder probe. Retrieved Mar 15, 2019 from https://www.reuters.com.

Jung, C. (2018). How Beijing’s propaganda dents China’s image, rather than burnishes it. Retrieved Mar 15, 2019 from https://www.scmp.com.

Kapferer, J.-N. (2015). Kapferer on luxury: how luxury brands can grow yet remain rare. London: Kogan Page.

Kapferer, J.-N., & Valette-Florence, P. (2016). Beyond rarity: The paths of luxury desire how luxury brands grow yet remain desirable. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 25(2), 120–133.

Kees, J., Berry, C., Burton, S., & Sheehan, K. (2017). An analysis of data quality: Professional panels, student subject pools, and amazon's mechanical turk. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 141–155.

Keillor, B. D., & Hult, T. M. G. (1999). A five-country study of national identity: Implications for international marketing research and practice. International Marketing Review, 16(1), 65–84.

Kemp, S. (1998). Perceiving Luxury and Necessity. Journal of Economic Psychology, 19(5), 591–606.

Kinnick, K. N. (2003). How corporate America grieves: Responses to September 11 in public relations advertising. Public Relations Review, 29(4), 443–459.

Klein, J. G., Ettenson, R., & Morris, M. D. (1998). The animosity model of foreign product purchase: An empirical test in the People's Republic of China. The Journal of Marketing, 62(1), 89–100.

Kosterman, R., & Feshbach, S. (1989). Toward a Measure of patriotic and nationalistic attitudes. Political Psychology, 1(2), 257–274.

Krämer, B. (2014). Media populism: A conceptual clarification and some theses on its effects. Communication Theory, 24(1), 42–60.

Krosnick, J. A. (1991). Response strategies for coping with the cognitive demands of attitude measures in surveys. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 5(3), 213–236.

Lantz, G., & Loeb, S. (1998). An examination of the community identity and purchase preferences using the social identity approach. In J. W. Alba & J. W. Hutchinson (Eds.), NA - Advances in consumer research (pp. 486–491). UT: Provo.

Lasswell, H. D. (1927). The theory of political propaganda. American Political Science Review, 21(3), 627–631.

Lee, S. Y., Zhang, W., & Abitbol, A. (2019). What makes CSR communication lead to CSR participation? Testing the mediating effects of CSR associations, CSR credibility, and organization-public relationships. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(2), 413–429.

Lein, S. (2018). Why sustainable branding matters. Retrieved Mar 20, 2019 from https://www.forbes.com.

Maignan, I. (2001). Consumers' perceptions of corporate social responsibilities: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Business Ethics, 30(1), 57–72.

MarketWatch. (2019). Luxury Car Market Share,Size 2019 Industry Development Analysis, Global Trends, Growth Factors, Cagr Status, Industry Insights by Top Key Players and, Forecast to 2024. https://www.marketwatch.com.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253.

Mazis, M. B., Settle, R. B., & Leslie, D. C. (1973). Elimination of phosphate detergents and psychological reactance. Journal of Marketing Research, 10(4), 390–395.

McMellon, C. A., & Long, M. (2006). Sympathy, Patriotism and cynicism: Post-9/11 New York City newspaper advertising content and consumer reactions. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 28(1), 1–18.

Moon, L. (2019). Chinese shoppers say they would Shun American Brands during the world’s busiest 24 hours of online shopping. https://www.scmp.com.

Morsing, M., & Roepstorff, A. (2015). CSR as corporate political activity: Observations on Ikea’s CSR identity-image dynamics. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(2), 395–409.

Muller, P., Schemer, C., Wettstein, M., Schulz, A., Wirz, D. S., Engesser, S., et al. (2017). The polarizing impact of news coverage on populist attitudes in the public: Evidence from a panel study in four European democracies. Journal of Communication, 67(6), 968–992.

Nai, A. (2018). Fear and loathing in populist campaigns? Comparing the communication style of populists and non-populists in elections worldwide. Journal of Political Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2018.1491439.

Nijssen, E. J., & Douglas, S. P. (2004). Examining the animosity model in a country with a high level of foreign trade. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21(1), 23–38.

Oppenheimer, D. M., Meyvis, T., & Davidenko, N. (2009). Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 867–872.

Ouellet, J.-F. (2007). Consumer racism and its effects on domestic cross-ethnic product purchase: An empirical test in the United States, Canada, and France. Journal of Marketing, 71(1), 113–128.

Papadopoulos, N., Cleveland, M., Bartikowski, B., & Yaprak, A. (2018). Of countries, places and product/brand place associations: An inventory of dispositions and issues relating to place image and its effects. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 27(7), 735–753.

Reuters (2019). China's Xi Appeals to Youth Patriotism on Centenary of Student Protests. Retrived Aug 1, 2019 from https://uk.reuters.com.