Abstract

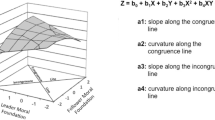

Ethical leadership research has primarily relied on social learning and social exchange theories. Although these theories have been generative, additional theoretical perspectives hold the potential to broaden scholars’ understanding of ethical leadership’s effects. In this paper, we examine moral typecasting theory and its unique implications for followers’ leader-directed citizenship behavior. Across two studies employing both survey-based and experimental methods, we offer support for three key predictions consistent with this theory. First, the effect of ethical leadership on leader-directed citizenship behavior is curvilinear, with followers helping highly ethical and highly unethical leaders the least. Second, this effect only emerges in morally intense contexts. Third, this effect is mediated by the follower’s belief in the potential for prosocial impact. Our findings suggest that a follower’s belief that his or her leader is ethical has meaningful, often counterintuitive effects that are not predicted by dominant theories of ethical leadership. These results highlight the potential importance of moral typecasting theory to better understand the dynamics of ethical leadership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although most leaders are themselves followers of higher level leaders, we suggest that in general a given follower will seldom experience this first-hand. For instance, a low-level employee will seldom directly observe high-level meetings between his leader and a top management team. In other words, on average, leaders are more likely to be perceived as moral agents than employees not in leadership positions.

Of course, unethical leaders are likely to receive less help from their followers for a wide variety of reasons. However, the curvilinear hypothesis is uniquely predicted by moral typecasting theory. For instance, social exchange theory might explain why unethical leaders receive little help from their followers, but it does not predict a curvilinear effect.

We did not use Settoon and Mossholder’s (2002) task-focused scale because the items imply that the follower is able to help the leader with his or her specific job duties, and many followers might lack the knowledge or ability to engage in this type of helping behavior.

References

Ashforth, B., Gioia, D., Robinson, S., & Treviño, L. (2008). Re-viewing organizational corruption. Academy of Management Review, 33, 670–684.

Avolio, B. (2007). Promoting more integrative strategies for leadership theory-building. American Psychologist, 62, 25–33.

Avolio, B., Walumbwa, F., & Weber, T. (2009). Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 421–441.

Baldwin, M. (1992). Relational schema and processing of social information. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 461–484.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Barnes, C. M., Schaubroeck, J., Huth, M., & Ghumman, S. (2011). Lack of sleep and unethical conduct. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115, 169–180.

Bastian, B., Laham, S., Wilson, S., Haslam, N., & Koval, P. (2011). Blaming, praising, and protecting our humanity: The implications of everyday dehumanization for judgments of moral status. British Journal of Social Psychology, 50, 469 –483.

Bird, F., & Waters, J. (1989). The moral muteness of managers. California Management Review, 32, 73–88.

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: John Wiley.

Bornstein, R. (1994). Dependency as a social cue: A meta-analytic review of research on the dependency—helping relationship. Journal of Research in Personality, 28, 182–213.

Broverman, I., Vogel, S., Broverman, D., Clarkson, F., & Rosenkrantz, P. (1972). Sex-role stereotypes: A current appraisal. Journal of Social Issues, 28, 59–78.

Brown, M., & Mitchell, M. (2010). Ethical and unethical leadership: Exploring new avenues for future research. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20, 583-616.

Brown, M., & Treviño, L. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadership Quarterly, 91, 954–962.

Brown, M., Treviño, L., & Harrison, D. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 117–134.

Butterfield, K., Treviño, L., & Weaver, G. (2000). Moral awareness in business organizations: Influences of issue-related and social context factors. Human Relations, 53, 981–1018.

Caprara, G., & Steca, P. (2005). Self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of prosocial behavior conducive to life satisfaction across ages. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24, 191–217.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd edn.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

De Cremer, D., Mayer, D., van Dijke, M., Schouten, B., & Bardes, M. (2009). When does self-sacrificial leadership motivate prosocial behavior? It depends on followers’ prevention focus. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 887–899.

Doh, J. (2003). Can leadership be taught? Perspectives from management educators. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 2, 54–67.

Doherty, A. (1997). The effect of leader characteristics on the perceived transformational/transactional leadership and impact of interuniversity athletic administrators. Journal of Sport Management, 11, 275–285.

Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38, 1715–1759.

Dvir, T., & Shamir, B. (2003). Follower developmental characteristics as predicting transformational leadership: A longitudinal field study. Leadership Quarterly, 14, 327–344.

Eagly, A., & Chin, J. (2010). Diversity and leadership in a changing world. American Psychologist, 65, 216–224.

Eagly, A., & Crowley, M. (1986). Gender and helping behavior: A meta-analytic review of the social psychological literature. Psychological Bulletin, 100, 283–308.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 21, 1–22.

Fehr, R., Yam, K. C., & Dang, C. T. (2015). Moralized leadership: The construction and consequences of ethical leader perceptions. Academy of Management Review, 2, 182–209.

Fiske, A. (1992). The four elementary forms of sociality: Framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychological Review, 99, 689–723.

Fletcher, J. K. (2004). The paradox of postheroic leadership: An essay on gender, power, and transformational change. Leadership Quarterly, 15(5), 647–661.

Frey, B. (2000). The impact of moral intensity on decision making in a business context. Journal of Business Ethics, 26, 181–195.

Graen, G., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi- level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 6, 219–247.

Grant, A. M. (2007). Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Academy of Management Review, 32, 393–417.

Grant, A. M. (2008a). The significance of task significance: Job performance effects, relational mechanisms, and boundary conditions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 108–124.

Grant, A. M. (2008b). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 48–58.

Grant, A. M., & Campbell, E. M. (2007). Doing good, doing harm, being well and burning out: The interactions of perceived prosocial and antisocial impact in service work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80, 665–691.

Grant, A. M., Campbell, E. M., Chen, G., Cottone, K., Lapedis, D., & Lee, K. (2007). Impact and the art of motivation maintenance: The effects of contact with beneficiaries on persistence behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103, 53–67.

Grant, A. M., & Gino, F. (2010). A little thanks goes a long way: Explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology, 98, 946–955.

Gray, H., Gray, K., & Wegner, D. (2007). Dimensions of mind perception. Science, 315, 619.

Gray, K. (2010). Moral transformation: Good and evil turn the weak into the mighty. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1, 253–258.

Gray, K., & Wegner, D. (2009). Moral typecasting: Divergent perceptions of moral agents and moral patients. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 505–520.

Gray, K., & Wegner, D. (2010). Dimensions of moral emotions. Emotion Review, 3, 258–260.

Gray, K., & Wegner, D. (2011). Morality takes two: Dyadic morality and mind perception. In P. Shaver & M. Mikulincer (Eds.), The social psychology of morality (pp. 109–127). Washington, DC: APA Press.

Gray, K., Young, L., & Waytz, A. (2012). Mind perception is the essence of morality. Psychological Inquiry, 23, 101–124.

Greitemeyer, T., & Osswald, S. (2010). Effects of prosocial video games on prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 211–221.

Haidt, J. (2008). Morality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 65–72.

Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and condition process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychological of interpersonal relationships. New York: Wiley.

Highhouse, S. (2009). Designing experiments that generalize. Organizational Research Methods, 12, 554–566.

Hollenbeck, J. R. (2008). The role of editing in knowledge development: Consensus shifting and consensus creation. In Y. Baruch, A. M. Konrad, H. Aguinis & W. H. Starbuck (Eds.), Opening the black box of editorship (pp. 16–26). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jones, T. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16, 366–395.

Kacmar, K., Bachrach, D., Harris, K., & Zivnuska, S. (2011). Fostering good citizenship through ethical leadership: Exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 633 –642.

Kalshoven, K., Hartog, D., De Hoogh, D., A (2011). Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Leadership Quarterly, 22, 51–69.

Kelley, P., & Elm, D. (2003). The effect of context on moral intensity of ethical issues: Revising Jones’s issue-contingent model. Journal of Business Ethics, 48, 139–154.

May, D., & Pauli, K. (2002). The role of moral intensity in ethical decision making: A review and investigation of moral recognition, evaluation, and intention. Business and Society, 41, 84–117.

Mayer, D., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 151–171.

Mayer, D., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108, 1–13.

McMahon, J., & Harvey, R. (2006). An analysis of the factor structure of Jones’ moral intensity construct. Journal of Business Ethics, 64, 381–404.

McMahon, J. M., & Harvey, R. J. (2007). The effect of moral intensity on ethical judgment. Journal of Business Ethics, 72, 335–357.

Miao, Q., Newman, A., Yu, J., & Xu, L. (2013). The relationship between ethical leadership and unethical pro-organizational behavior: Linear or curvilinear effects? Journal of Business Ethics, 116, 641–653.

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2015). Ethical leadership: Meta-analytic evidence of criterion-related and incremental validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 948–965.

Nohria, N., & Khurana, R. (2010). Handbook of leadership theory and practice. Harvard Business Press.

Piccolo, R., Greenbaum, R., Hartog, D., & Folger, R. (2010). The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31, 259–278.

Podsakoff, P., Whiting, S., Welsh, D., & Mai, M. (2013). Surveying for “artifacts”: The susceptibility of the OCB-performance evaluation relationship to common rater, item, and measurement context effects. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98, 863–874.

Reynolds, S. (2006). Moral awareness and ethical predispositions: Investigating the role of individual differences in the recognition of moral issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 233–243.

Rosette, A. S., Leonardelli, G. J., & Phillips, K. W. (2008). The White standard: Racial bias in leader categorization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 758–777.

Rubin, R., Dierdorff, E., & Brown, M. (2010). Do ethical leaders get ahead? Exploring ethical leadership and promotability. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20, 215–236.

Schaubroeck, J., Hannah, S., Avolio, B., Kozlowski, S., Lord, R., Treviño, L., Dimotakis, N., & Peng, A. (2012). Embedding ethical leadership within and across organizational levels. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 1053–1078.

Settoon, R., & Mossholder, K. (2002). Relationship quality and relationship context as antecedents of person- and task-focused interpersonal citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 255–267.

Shamir, B. (2007). From passive recipients to active co-producers—The roles of followers in the leadership process. In B. Shamir, R. Pillai, M. Bligh & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), Follower-centered perspectives on leadership: A tribute to J. R. Meindl. Stamford, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Stouten, J., van Dijke, M. H., Mayer, D., De Cremer, D., & Euwema, M. (2013). Can a leader be seen as too ethical? The curvilinear effects of ethical leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 24, 680–695.

Tepper, B. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 2, 178–190.

Tourish, D. (2013). The dark side of transformational leadership: A critical perspective. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Tsalikis, J., Seaton, B., & Shepherd, P. (2008). Relative importance measurement of the moral intensity dimensions. Journal of Business Ethics, 80, 613–626.

Twenge, J., Baumeister, R., DeWall, C., Ciarocco, N., & Bartels, J. (2007). Social exclusion decreases prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 56–66.

Uhl-Bien, M. (2006). Relational leadership theory: Exploring the social processes of leadership and organizing. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 654–676.

Uhl-Bien, M., Riggio, R. E., Lowe, K. B., & Carsten, M. K. (2014). Followership theory: A review and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 25, 83–104.

van Knippenberg, B., & van Knippenberg, D. (2005). Leader self-sacrifice and leadership effectiveness: The moderating role of leader prototypicality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 25–37.

Vianello, M., Galliani, E. M., & Haidt, J. (2010). Elevation at work: The effects of leaders’ moral excellence. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 390–411.

Walumbwa, F., Mayer, D., Wang, P., Wang, H., Workman, K., & Christensen, A. (2011). Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader-member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115, 204–213.

Walumbwa, F., & Schaubroeck, J. (2009). Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating role of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1275–1286.

Waytz, A., Gray, K., Epley, N., & Wegner, D. (2010). Causes and consequences of mind perception. Trends in Cognitive Science, 14, 383–388.

Wegner, D., & Vallacher, R. (1977). Implicit psychology: An introduction to social cognition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Yam, K. C., Fehr, R., Keng-Highberger, F., Klotz, A., & Reynolds, S. J. (2016). Out of control: A self-control perspective on the link between surface acting and abusive supervision. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101, 292–301.

Yukl, G., Mahsud, R., Hassan, S., & Prussia, G. (2013). An improved measure of ethical leadership. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 20, 38–48.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank Christopher Barnes, Terry Mitchell, and Scott Reynolds for constructive comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Appendices

Appendix A: Items in Scales

Ethical leadership (Pilot Study and Study 1; Brown et al. 2005)

-

1.

My supervisor conducts his/her personal life in an ethical manner

-

2.

My supervisor defines success not just by results but also the way that they are obtained

-

3.

My supervisor listens to what employees have to say

-

4.

My supervisor disciplines employees who violate ethical standards

-

5.

My supervisor makes fair and balanced decisions

-

6.

My supervisor can be trusted

-

7.

My supervisor discusses business ethics or values with employees

-

8.

My supervisor sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics

-

9.

My supervisor has the best interests of employees in mind

-

10.

When making decisions, my supervisor asks “what is the right thing to do?”

Moral intensity (Study 1; adapted from McMahon and Harvey 2006)

-

1.

The consequences of my organization’s actions (positive or negative) are significant

-

2.

The overall good or bad produced by my organization’s actions is very high

-

3.

There is a high likelihood that my organization’s actions help or harm people

-

4.

The decisions that my organization makes are likely to help or harm many people

-

5.

My organization’s actions are likely to help or harm people in the immediate future

-

6.

The positive or negative effects of my organization’s actions are likely to be felt very quickly

Leader-directed citizenship behavior (Study 1; adapted from Settoon and Mossholder 2002)

-

1.

My supervisee listens to me when I have something to get off my chest

-

2.

My supervisee takes time to listen to my problems and worries

-

3.

My supervisee takes a personal interest in me

-

4.

My supervisee shows concern and courtesy toward me, even under the most trying business situations

-

5.

My supervisee takes an extra effort to understand the problems I face

-

6.

My supervisee goes out of the way to make me feel welcome

-

7.

My supervisee tries to cheer me up when I am having a bad day

-

8.

My supervisee compliments me when I succeed at work

Perceived potential for prosocial impact (Study 2; adapted from Grant 2008a; Grant and Campbell 2007)

-

1.

I feel that I can make a positive difference in John’s life

-

2.

I can really make John’s life better

-

3.

I am very aware of the ways in which I can benefit John

-

4.

I am very conscious of the positive impact that I can have on John

-

5.

I can have a positive impact on John on a regular basis

Moral agency (Pilot Study; adapted from Gray and Wegner 2009)

-

1.

My supervisor is responsible for his/her own behavior

-

2.

My supervisor’s behavior is intentional

-

3.

My supervisor deserves the praise/blame for the action he/she commits

Moral patiency

-

1.

My supervisor is in frequent need of help

-

2.

My supervisor is very dependent on the help of others

-

3.

My supervisor often requires the assistance of others to succeed

-

4.

My supervisor needs other people to succeed

-

5.

My supervisor cannot manage things well on his/her own

Appendix B: Study 2 Leadership Vignettes

High Moral Intensity/High Ethical Leadership Condition

John is Chief Director of a medical research laboratory in the United States. He currently has 50 full-time employees working in his laboratory. The mission of his lab is to conduct research to help eradicate cancer in the United States. In the past few years, his lab’s research has made major medical advances, influencing government policy and promising to improve the lives of thousands of people.

As a leader of the team, John always has the best interests of his employees in mind and always listens to what employees have to say. The decisions he makes at work are widely regarded as fair. He defines success not just by results but also the way they are obtained. John’s employees often regard him as a person who leads with moral conviction. Several visitors to his lab have also made praiseworthy comments about the values that underlie his leadership.

High Moral Intensity/Control Condition

John is Chief Director of a medical research laboratory in the United States. He currently has 50 full-time employees working in his laboratory. The mission of his lab is to conduct research to help eradicate cancer in the United States. In the past few years, his lab’s research has made major medical advances, influencing government policy and promising to improve the lives of thousands of people.

High Moral Intensity/Low Ethical Leadership Condition

John is Chief Director of a medical research laboratory in the United States. He currently has 50 full-time employees working in his laboratory. The mission of his lab is to conduct research to help eradicate cancer in the United States. In the past few years, his lab’s research has made major medical advances, influencing government policy and promising to improve the lives of thousands of people.

As the leader of the team, John rarely keeps the best interests of his employees in mind and rarely listens to what employees have to say. The decisions he makes at work are widely regarded as unfair. He defines success by results, but is indifferent about the way they are obtained. John’s employees often regard him as a person who leads without moral conviction. Several visitors to his lab have also made critical comments about the values that underlie his leadership.

Low Moral Intensity/High Ethical Leadership Condition

John is Chief Director of a geology research laboratory in the United States. He currently has 50 full-time employees working in his laboratory. The mission of his lab is to conduct research to help identify different types of rock formations. In the past few years, his lab’s research has made some moderate advances, increasing geologists’ understanding of rock formations.

As a leader of the team, John always has the best interests of his employees in mind and always listens to what employees have to say. The decisions he makes at work are widely regarded as fair. He defines success not just by results but also the way they are obtained. John’s employees often regard him as a person who leads with moral conviction. Several visitors to his lab have also made praiseworthy comments about the values that underlie his leadership.

Low Moral Intensity/Control Condition

John is Chief Director of a geology research laboratory in the United States. He currently has 50 full-time employees working in his laboratory. The mission of his lab is to conduct research to help identify different types of rock formations. In the past few years, his lab’s research has made some moderate advances, increasing geologists’ understanding of rock formations.

Low Moral Intensity/Low Ethical Leadership Condition

John is Chief Director of a geology research laboratory in the United States. He currently has 50 full-time employees working in his laboratory. The mission of his lab is to conduct research to help identify different types of rock formations. In the past few years, his lab’s research has made some moderate advances, increasing geologists’ understanding of rock formations.

As the leader of the team, John rarely keeps the best interests of his employees in mind and rarely listens to what employees have to say. The decisions he makes at work are widely regarded as unfair. He defines success by results, but is indifferent about the way they are obtained. John’s employees often regard him as a person who leads without moral conviction. Several visitors to his lab have also made critical comments about the values that underlie his leadership.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yam, K.C., Fehr, R., Burch, T.C. et al. Would I Really Make a Difference? Moral Typecasting Theory and its Implications for Helping Ethical Leaders. J Bus Ethics 160, 675–692 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3940-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3940-0