Abstract

Purpose

Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among post-menopausal breast cancer patients is an important survivorship care issue. We explored factors associated with endocrine therapy adherence and survival in a large real-world population-based study.

Methods

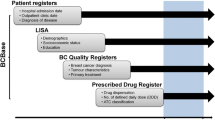

We used health administrative databases to follow women (aged ≥ 66 years) who were diagnosed with breast cancer and started on adjuvant endocrine therapy from 2005 to 2010. Adherence was measured by medical possession ratio (MPR) and characterized as low (< 39% MPR), intermediate (40–79% MPR), or high (≥ 80% MPR) over a 5-year period. We investigated factors associated with adherence using a multinomial logistic regression model. Factors associated with all-cause mortality (5 years after starting endocrine therapy) were investigated using a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

We identified 5692 eligible patients starting adjuvant endocrine therapy who had low, intermediate, and high adherence rates of 13% (n = 749), 13% (n = 733), and 74% (n = 4210), respectively. Lower rates of adherence were associated with increased age [low vs. high adherence: odds ratio (OR) 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.05 (per year); intermediate vs. high adherence: OR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.04 (per year)]. High adherence was associated with previous use of adjuvant chemotherapy (low versus high adherence OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.30–0.59) and short-term follow-up with a medical oncologist within 4 months of starting endocrine therapy (low versus high adherence OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.69–0.99). Unadjusted analysis showed increased survival among patients with high endocrine therapy adherence. However, an independent association was no longer clearly detected after controlling for confounders.

Conclusion

Interventions to improve adjuvant endocrine therapy adherence are warranted. Non-adherence may be a more significant issue among elderly patients. Short-term follow-up visit by a patient’s medical oncologist after starting endocrine therapy may help to improve compliance.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Pan H, Gray R, Davies C et al (2016) Predictors of recurrence during years 5–14 in 46,138 women with ER+ breast cancer allocated 5 years only of endocrine therapy (ET). J Clin Oncol 34:505

Davies C et al (2013) Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years after diagnosis of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: ATLAS, a randomised trial. Lancet 381(9869):805–816

Gray R (2013) aTTom: long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years in 6,934 women with early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 31:5

Goss PE et al (2016) Extending aromatase-inhibitor adjuvant therapy to 10 years. N Engl J Med 375(6):209–219

Chlebowski RT, Kim J, Haque R (2014) Adherence to endocrine therapy in breast cancer adjuvant and prevention settings. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 7(4):378–387

Murphy CC et al (2012) Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors in clinical practice: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 134(2):459–478

Osterberg L, Blaschke T (2005) Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 353(5):487–497

ICES., www.ices.on.ca. Accessed 1 May 2019

Charlson ME et al (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA (1992) Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 45(6):613–619

Tu K et al (2010) Validation of physician billing and hospitalization data to identify patients with ischemic heart disease using data from the Electronic Medical Record Administrative data Linked Database (EMRALD). Can J Cardiol 26(7):e225–e228

Schultz SE et al (2013) Identifying cases of congestive heart failure from administrative data: a validation study using primary care patient records. Chronic Dis Inj Can 33(3):160–166

Hux JE et al (2002) Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care 25(3):512–516

Jaakkimainen RL et al (2016) Identification of physician-diagnosed alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in population-based administrative data: a validation study using family physicians’ electronic medical records. J Alzheimers Dis 54(1):337–349

Fiest KM et al (2014) Systematic review and assessment of validated case definitions for depression in administrative data. BMC Psychiatry 14:289

O’Donnell S, G. Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System Osteoporosis Working (2013) Use of administrative data for national surveillance of osteoporosis and related fractures in Canada: results from a feasibility study. Arch Osteoporos 2013(8):143

Alotaibi GS et al (2015) The validity of ICD codes coupled with imaging procedure codes for identifying acute venous thromboembolism using administrative data. Vasc Med 20(4):364–368

Peterson AM et al (2007) A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health 10(1):3–12

Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA (2007) Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 297(2):177–186

Chirgwin JH et al (2016) Treatment adherence and its impact on disease-free survival in the breast international group 1-98 trial of tamoxifen and letrozole, alone and in sequence. J Clin Oncol 34(21):2452–2459

Verma S et al (2011) Patient adherence to aromatase inhibitor treatment in the adjuvant setting. Curr Oncol 18(Suppl 1):S3–S9

Trialists Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative, G et al (2011) Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 378(9793):771–784

Coombes RC et al (2004) A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med 350(11):1081–1092

Baum M et al (2002) Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet 359(9324):2131–2139

Wigertz A et al (2012) Adherence and discontinuation of adjuvant hormonal therapy in breast cancer patients: a population-based study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 133(1):367–373

Huiart L, Dell’Aniello S, Suissa S (2011) Use of tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors in a large population-based cohort of women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer 104(10):1558–1563

Hershman DL et al (2010) Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 28(27):4120–4128

van Herk-Sukel MP et al (2010) Half of breast cancer patients discontinue tamoxifen and any endocrine treatment before the end of the recommended treatment period of 5 years: a population-based analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 122(3):843–851

Partridge AH et al (2003) Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 21(4):602–606

Partridge AH et al (2008) Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 26(4):556–562

Pistilli B, Paci A, Michaels S et al (2018) Serum assessment of non-adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET) among premenopausal patients in the prospective multicenter CANTO cohort. Ann Oncol 29(8 Suppl):1850

Saha P et al (2017) Treatment efficacy, adherence, and quality of life among women younger than 35 years in the international breast cancer study group text and soft adjuvant endocrine therapy trials. J Clin Oncol 35(27):3113–3122

Puts MT et al (2014) Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 25(3):564–577

Nekhlyudov L et al (2011) Five-year patterns of adjuvant hormonal therapy use, persistence, and adherence among insured women with early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 130(2):681–689

Farias AJ, Du XL (2017) Association between out-of-pocket costs, race/ethnicity, and adjuvant endocrine therapy adherence among medicare patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 35(1):86–95

Riley GF et al (2011) Endocrine therapy use among elderly hormone receptor-positive breast cancer patients enrolled in Medicare Part D. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. https://doi.org/10.5600/mmrr.001.04.a04

Kimmick G et al (2009) Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 27(21):3445–3451

Madarnas Y et al (2011) Models of care for early-stage breast cancer in Canada. Curr Oncol 18(Suppl 1):S10–S19

Follow-up after treatment for breast cancer (1998) The steering committee on clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer. CMAJ 158(Suppl 3):S65–S70

Runowicz CD et al (2016) American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. J Clin Oncol 34(6):611–635

Halpern MT et al (2015) Models of cancer survivorship care: overview and summary of current evidence. J Oncol Pract 11(1):e19–e27

Heiney SP et al (2018) A systematic review of interventions to improve adherence to endocrine therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 173(3):499–510

Dickinson R et al (2014) Using technology to deliver cancer follow-up: a systematic review. BMC Cancer 14:311

Grunfeld E et al (2011) Evaluating survivorship care plans: results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29(36):4755–4762

Cheng KKF et al (2017) Home-based multidimensional survivorship programmes for breast cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8:CD011152

Ziller V et al (2013) Influence of a patient information program on adherence and persistence with an aromatase inhibitor in breast cancer treatment–the COMPAS study. BMC Cancer 13:407

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the ICES Western site. ICES is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). Core funding for ICES Western is provided by the Academic Medical Organization of Southwestern Ontario (AMOSO), the Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry (SSMD), Western University, and the Lawson Health Research Institute (LHRI). This research was also funded by an AMOSO opportunities Grant. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) and Cancer Care Ontario (CCO). The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding or data sources. We thank IMS Brogan Inc. for use of their Drug Information Database. No endorsement by ICES, MOHLTC, AMOSO, SSMD, LHRI, CIHI, or CCO is intended or should be inferred.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

KIP has consulted for Pfizer, Roche, Amgen, Novartis, Eisai, Genomic Health, and Myriad Genetics Laboratories. TV has consulted for Novartis and Roche. AL has consulted for AstraZeneca and received honoraria from Varian Medical Systems Inc. JR has received honoraria from F. Hoffmann-La Roche. All other authors report no conflicts.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. The use of data in this project was authorized under Section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require review by a research ethics board.

Informed consent

ICES is a prescribed entity under Section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act. Section 45 authorizes ICES to collect personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of analysis or compiling statistical information with respect to the management of, evaluation or monitoring of, the allocation of resources to, or planning for all or part of the health system. This project was conducted under Section 45, and approved by ICES’ Privacy and Compliance Office.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Blanchette, P.S., Lam, M., Richard, L. et al. Factors associated with endocrine therapy adherence among post-menopausal women treated for early-stage breast cancer in Ontario, Canada. Breast Cancer Res Treat 179, 217–227 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05430-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05430-6