Abstract

Numerous conservation activities in Africa have been of little effect. In this study, we investigate socio-economic trade-offs that might have been overlooked, yet may undermine conservation action in discret pathways. Data was collected in three study sites with fragile forest ecosystems in south-eastern Kenya, through locally adapted structured surveys and semi-structured expert guides. These analyses are drawn from 827 structured surveys and 37 expert interviews, which were done during 2016–2018. We found general coherences between age, gender, ethnicity, indigenous knowledge, formal education, and higher incomes, which shapes forest conservation attitudes. Indigenous knowledge is marginal, and most people with formal education in the rural setting are likely to be young without legal land rights or among the minority with off-farm employment. The reluctance to address historical land injustices and inequitable sharing of entitlements and management authority overrides positive attitudes and intentions towards forest conservation in all three study sites. However, we found considerable discrepancies among the three study sites. For Arabuko Sokoke forest, the awareness of forest conservation was relatively low when compared with the other two study sites. Forests play a major role against the backdrop of resource use in all three regions. But, different ecosystem services are used among the three study sites. For environmental education and communication, internet plays a comparatively minor role. Strategies to preserve forest differ among the three study sites: Reforestation is proposed in cloud forests of Taita Hills and riparian forests, whereas off-farm employment and alternative income sources plays a major role in Arabuko Sokoke forest. Our findings underline that locally specific conservation management is needed to conduct efficient nature conservation, particularly in countries with very heterogeneous ethnicities and environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Anthropocene is characterized by rapid destruction and degradation of intact ecosystems (Jaeger, 2000; Hansen et al. 2020), and subsequent loss of biodiversity and ecosystem functions (Myers et al. 2000; Balmford et al. 2001). This may also undermine human livelihood quality (Büscher & Whande, 2007; Agrawal et al. 2008). Achieving a win-win situation between ecological conservation and human wellbeing remains an urgent global concern (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005). In the African context, the conservation of forests and woodlands is sporadic (Balmford et al. 2001; Miles et al. 2006) and deserves more attention (Riggio et al. 2019; Nzau et al. 2020; 2021a). An efficient nature conservation is a challenge, especially in rapidly shifting socio-economic landscapes (Igoe & Brockington, 2007; Githiru, 2007; Kavousi et al. 2020).

Participatory Forest Management (PFM) is often considered as a fundamental approach towards reconciling biodiversity conservation and human livelihood needs (Kellert et al. 2000; Schreckenberg & Luttrell, 2009; Vyamana, 2009; Nzau et al. 2020). PFM encompasses diverse initiatives towards the co-management of natural resources by varied actors, including state agencies, civil society, and local people (Wily, 2002; Schreckenberg & Luttrell, 2009). Management of natural resources is understood as the right to regulate internal use patterns and transform the resource by making improvements (Ostrom & Schlager, 1996) wherein two or more social actors negotiate, define, and guarantee amongst themselves a fair sharing of the management functions, entitlements and responsibilities for a given area or set of natural resources (Borrini-Feyerabend et al. 2007). Although many different co-management principles exist within PFM schemes, the extent to which these principles are applicable in real-world scenarios depends on local conditions (Kellert et al. 2000; Brockington, 2004; Borrini-Feyerabend et al. 2007; Schreckenberg & Luttrell, 2009). Numerous case studies from Africa have revealed the shortcomings of PFM (Githiru, 2007; Ming’ate & Bollig, 2016).

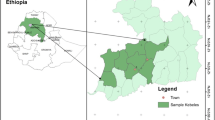

In this study, we analyze coherences and trade-offs that underpin the acceptance and legitimacy of conservation initiatives within PFM schemes in three different study sites with fragile forest ecosystems across south-eastern Kenya. We consider gallery forests in semiarid drylands in Kitui County, the dryland coastal Arabuko Sokoke forest, and the cloud forests of Taita Hills. While these three regions represent divergent agro-ecological, topographical, and geophysical conditions, they all are characterized by severe human demographic and rapid land-use pressure and a loss of natural forest with subsequent losses of natural habitats, species, and ecosystem functions (Habel et al. 2015). We conducted structured surveys among local smallholder farmers living in close vicinity of the respective forests (< 0.5 km distant). Additionally, we performed semi-structured interviews with representatives of different governmental and non-governmental agencies, working in the field of land management, forestry, agriculture, and/or nature and resource conservation. Data were collected during the years 2016–2019. Based on the results obtained we will answer the following questions:

-

1.

Which socio-economic predictors impact the awareness, perceptions, and attitudes towards biodiversity for the respondents of the study sites?

-

2.

Do environmental communication sources influence biases and conservation behaviors for the three study sites?

-

3.

Which socio-cultural conditions are the prerequisite for successful Participatory Forest Management?

Materials and methods

Study sites

This study was carried out in three areas in south-eastern Kenya (Fig. 1). These areas include the gallery forests along Nzeeu River in Kitui County, the coastal dryland Arabuko-Sokoke forest (ASF) along the coastline of the Indian Ocean in Kilifi County, and the cloud forests of Taita Hills, in Taita-Taveta County. All these three areas harbor fragile ecosystems with high levels of biodiversity, including many endemic plant and animal species (see Burgess et al. 1998). Despite the partially strict protection (especially for ASF and some cloud forest fragments of Taita Hills), these forest ecosystems suffer extremely under illegal deforestation and the exploitation of natural resources (Burgess et al. 1998). All three areas differ in respect of abiotic conditions (semi-arid, high mountain, coastal region), forest types (gallery forest, dry coastal forest, cloud forest), and ethnicity of the local human population (Kamba in Kitui County, Giriama and Waatha around ASF, Taitas in Taita Hills). The dry coastal ASF is comparatively large forest fragment and officially protected, while the Taita Hills cloud forests and particularly the gallery forests along rivers in the semi-arid Kitui County are highly fragmented and anthropogenic modified, and invaded by exotic plant species (Teucher et al. 2018). A detailed description of the socio-economic status of each of the three study sites is given in Appendix S1.

Data collection

Data collection was done through a standardized questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed in English and subsequently translated into Swahili. In total, we obtained 827 filled questionairs (191 along the Nzeeu River in Kitui County, 336 around ASF, 300 around Taita Hill cloud forest fragments). We employed convenience sampling for the selection of survey participants. The sampling criteria included geographical proximity (< 0.5 km distant to the forest) to respective forests. The interviews were deliberately conducted exclusively with people living around the forest, as it can be assumed that these people benefit from the forest on the one hand (fruits, animals, wood, see REFS), but also suffer from human-wildlife conflicts (REFS). Further criterial were participant availability at the time of the survey, and their willingness to participate (Dörnyei, 2007). Household members nominated only one member per household, mainly the head of the household, to participate. A household encompassed all people who cooked together every evening. During expert interviews representatives of governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working in the field of land management, forestry, agriculture and conservation were asked an open-ended question regarding their ideas to protect the forest, namely reforestation, education and awareness, sustainable extraction of resources, streamlining and enforcement of environmental law, the providence of good quality water sources, co-management of natural resources, modern sustainable agriculture, alternative energy sources, nature-based livelihood opportunities and markets, and off-farm employment. These topics were used to judge the local priorities for forest conservation action. A detailed description of the questionnaire including the coding of answers is provided in Appendix S2. Data on the relevance and role of NGOs were only available for ASF and Taita, but not for Kitui County.

Data analyses

Qualitative answers were coded into themes using MAXQDA version 2020 (Appendix S2). We combined the answers to the questions about the benefits living close to the forest using principal component analysis (variance-covariance matrix) and used the dominant eigenvector EB as a proxy to the perceived benefits of near forest living. This eigenvector explained 33.9% of variance, higher values indicate more perceived benefits. Similarly, we calculated the dominant eigenvector EA (45.7% variance explanation) from the answers to the questions of whether plant and animals should be protected and to the willingness of keeping buffer zone and willingness of replanting trees. We interpreted this eigenvector as quantifying conservation awareness. For four paired questions regarding the awareness of ecological problems with respect to whole Kenya and own farm land (exotic tree plantations, land size, soil fertility, and erosion) we calculated the difference between the answer ranks for own farm and Kenya (ΔR = Rlocal – RKenya) as a relative proxy to perceived conservation problems. Negative values of ΔR indicate that the respondents see the local ecological problems of being small in comparison to the perceived status in whole Kenya.

We used generalized linear nested models (Poisson error structure, identity link function) as implemented in STATISTICA 12.0 to link our quantitative (number of children, farm size) and categorical predictors (study site, level of education) to the benefit and awareness indices (response variables). As we were mainly interested in the differences between the three study sites, site identify was nested within the other predictors. We compared quantitative answers with one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tuckey tests.

Results

Environmental and sociodemographic characteristics

Landscape and socioeconomic status of the local people strongly differed between the three study sites. Participants from ASF were comparably less educated, more often unemployed and had lower monthly incomes than people from Kitui County and Taita Hills (Fig. 2; Table 1). People from all three regions were comparatively poorly educated and had on average low income (Fig. 2). The mean number of people per household was 7.40 in the ASF study site, and 4.43 in Taita Hills (no data available for Kitui County).

Socio-economic comparisons of the participants in the three study sites. Except for children and land size (mean absolute values) mean codes according to the coding Table A1 are given. Error bars denote standard errors. The black lines denote the mean rank value. Gender: prevalence of female respondents, age classes: prevalence of older people in Kitui County, education and income: prevalence of lower education/income. Different letters above bars denote significant statistical differences between regions (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.01). The different colors of bars indicate the three different study sites. Red: ASF = Arabuko Sokoke forest; green: Kitui = riparian forests in Kitui County; blue: Taita = cloud forests of Taita Hills

Ecological awareness

The appreciation for the benefits of ecosystem services significantly differed between the study sites (Table 2). People from Kitui County perceived the socioeconomic and ecological benefits from close by forests highest, people from aSF lowest (Fig. 3a). Importantly, these differences were only marginally significant for people with higher education (Fig. 3a; Table 2). Within each study site, gender, age, monthly income, and numbers of children did not significantly influence the levels of perceived benefits (Table 2). Water availability, availability of fertile soils, good soils for brick production, and good pastures for livestock were of high relevance for survey participants living along with the gallery forests (Appendix B). At ASF and Taita Hills, the availability of shade (cooler microclimate) was important. In turn, illegal logging was listed as the leading threat to forest conservation in all three study sites.

a), b) Differences between the three study sites (red: ASL, green: Kitui County, blue: Taita) in the degrees of the index of perceived benefits from living near a forest EB and conservation awareness EA in dependence on the level of education. c) Perceived socioeconomic benefits living close to forest: IS: infrastructure, LA: land availability, TR: tradition. In c) no data for Taita Hills are available. Higher levels indicate higher awareness/benefits. Error bars denote standard error. The different colors of bars indicate the three different study sites. Red: Arabuko Sokoke forest; green: Riparian forests in Kitui County; blue: Cloud forests of Taita Hills

Awareness for conservation significantly differed between the three study sites (Fig. 3b; Table 2). Awareness was highest at the Kitui County site, and lowest at the ASF site (Fig. 3b). Again, other socioeconomic predictors did not significantly enter the glm model (Fig. 3b; Table 2).

Protection attitudes

Participants of all three regions voted in the majority in favour of plant and animal protection (all average answer scores > 4) but preferred the protection of plants over animals (p(F1,812) < 0.001), most pronounced in Taita Hills. Irrespective of study site, participants saw the local ecological situation better than the perceived situation in whole Kenya (Fig. 4a). Soil erosion (average score 4.30 ± 0.10; mean ± standard error) and soil fertility (4.33 ± 0.09) were most often mentioned in Kitui County (least negative ΔR values, Fig. 4a), while not seen as a problem in Taita Hills (2.94 ± 0.07 and 3.48 ± 0.06, respectively) and ASF (1.73 ± 0.06 and 3.08 ± 0.08, respectively). Also, too small fields were not mentioned as a problem (all average scores < 3.5), while the planting of non-indigenous trees was even seen slightly positively (all average scores < 3.0), most so in Kitui County (2.28 ± 0.0.16).

a) Perceived conservation problems ΔR of local people from Kitui County, ASF and Taita Hills. Personal ideas (b) and information sources (c) on how to improve forest conservation in their localities (proportions of mentioning with respect to the total number of answers to a given question). The vertical black line in c) denotes the average rescaled rank score indicating higher > 1) or lower (< 1) proportions of mentioning than expected from a random distribution around the mean score value. Errors denote standard errors. NGO data were not available for Kitui County. The different colors of bars indicate the three different study sites. Red: ASF = Arabuko Sokoke forest; green: Kitui = riparian forests in Kitui County; blue: Taita = cloud forests of Taita Hills

We found also highly significant differences between the study sites in respect of suggestions about conservation efforts (Fig. 4b). Reforestation was the major issue for respondents from Taita Hills, while in Kitui County sustainable resource extraction dominated. For local people from ASF, off-farm employment and alternative water sources dominated. Comparatively few mentions (< 10% respondents) gained alternative livelihoods, and water sources, as well as alternative energy sources (Fig. 4b). Rarely mentioned (≈ 10%) were also sustainable agriculture and participant resource management (Fig. 4b).

Overall, participants below the age of 50 considered off-farm employment as a key strategy to reduce pressure on forest ecosystems (ANOVA: F2,343 = 5.4, p < 0.01). Participants with higher formal education emphasized the need for reforestation (F3,732 = 5.6, p < 0.001), while sustainable extraction of natural resources was most often mentioned by respondents with secondary education and with higher income although the latter trends were only marginally significant (F3,731 = 2.8, p = 0.03 and F2,252 = 2.9, p = 0.06, respectively). Finally, people from Kitui County were significantly more prone to do mixed cropping (F2,817 = 37.2, p < 0.001), while people from ASF were less prone to abandon livestock grazing (F2,812 = 158.7, p < 0.001).

Environmental communication

Communication of information by local authorities and mass media (radio / TV) were often mentioned, while internet sources and NGOs played only a minor role in environmental communication (Fig. 4c). Importantly, mass media and local authorities were also assessed as being most useful information sources (Fig. 4c). The respondents found internet sources and at ASF also NGO information of being less useful (Fig. 4c). These general trends were independent of study site although there were significant site-specific differences. Particularly, the local people at ASF tended to be more skeptical against all sources of environmental information (Fig. 4c: F2,824 = 95.7, P < 0.001) and prefer alternative dissemination channels like group meetings, so called barrazas.

Discussion

Environmental and sociodemographic characteristics

We found that age, gender, ethnicity, indigenous knowledge, formal education, and higher incomes shapes attitudes towards the use of forest resources and forest conservation, across all three study sites. We found a rather low level of education and very low income for all three study sites. The people of ASF and Taita Hills positively affirm a general interest in forest conservation (Nzau et al. 2020; 2021a), although at different levels (with highest levels in Taita Hills). Most of the inhabitants record a historical interrelationship with conservation (Njogu, 2004; Shepheard-Walwyn, 2014). This becomes particularly clear when we take a closer look at the situation at ASF. This forest and region is currently experiencing accelerated urbanization, immigration influx, and lack of land-use planning (Bendzko et al. 2019). In this region, most people had lived for less than 20 years around the forest (REF). These factors accelerates parceling of land per capita (Bendzko et al. 2019; Schürmann et al. 2020; Nzau et al. 2020). Indigenous and local ecological knowledge systems are hardly integrated into the forest management of ASF, as is evident by the marginalization of the Waatha indigenous community there (Nzau et al. 2020). Residents surrounding ASF demonstrated the most negligible spatial bias yet showed the highest indifference towards forest conservation (Nzau et al. 2020; Nzau, 2021). The relatively high protection status and large size of the forest may contribute to illusions that the forest resources are finite (Nzau et al. 2020; Nzau, 2021). Furthermore, ASF still host large megafauna, such as elephants. The residents around the forest acknowledged the aesthetic (and touristic) value of wildlife, unlike in Kitui County and Taita Hills (Nzau et al. 2020; 2021a; Nzau, 2021). In comparison to ASF, the Taita Hills inhabitants showed a higher awareness of the threats to their forests due to their place-based experiences and longer relationship with their environment (Njogu, 2004; Hohenthal, 2018, Nzau, 2021). We found that age, gender and education shape behavior and attitudes towards forest and nature protection. In ASF, men and long-term residents were likely to be involved in making rules of forest use, while in Taita Hills, people with higher incomes and education likely to be involved. In both cases, many people were thereby excluded from decision-making processes, such as women, recent settlers, and full-time farmers (Nzau, 2021).

Relevance of forest ecosystem services

The fact that the forest is of great relevance for the quality of life of people was clear to most of the respondents. The appreciation for tangible ecosystem services provided by the forest was highest in Kitui County, a semi-arid region, where riparian river zones are often a lifeline for sustaining human livelihoods (Habel et al., 2018). Ecosystem services awareness differed among the three regions, and different services have been mentioned as being of relevance, such as soil i.e. soil fertility in Kitui County, and mesoclimatic conditions i.e. shade in Taita Hills and ASF. Awareness was highest in Kitui County and lowest in ASF. Surprisingly, there was only little consideration payed on water springs and access to water, which is of relevance to most of the regions, particularly the Taita Hills, where the planting of exotic eucalyptus trees caused the drying out of many springs (Hohenthal, 2018). Surprisingly, the planting of exotic trees is considered positive by the local people across all three study sites. The establishment of so-called wood-lots (tree plantations consisting of exotic, fast-growing tree species) is widespread in Kenya and provides a basic supply of timber and firewood, and is highly appreciated by the local population and authorities. In Kitui County, educated people notably showed a deep bias to protect plants over animals. Instead, people with no formal education in Kitui County, who were also likely to be older, showed heightened support for the protection of animals (this could be traced back to the histories of the inhabitants of these as revered hunters with intricate human-wildlife interrelationships (Steinhart, 2000; Nzau, 2021). On the contrary, older people in Taita (also likely not to have formal education) showed the least protection attitudes. Similarly, this negative relationship can be traced back to the wildlife conservation histories of the Taita Hills region, which is home to one of the oldest and largest National Parks in Kenya, The Tsavo (Njogu, 2004; Rülke et al. 2020; Nzau et al. 2021a).

Awareness and attitudes towards forest conservation

Historical land injustices and recent unequal benefit-sharing combats positive attitudes towards nature conservation (Njogu, 2004; Githiru, 2007; Nzau et al. 2020; 2021a). The promise of PFM to address these inequalities (see Kellert et al. 2000) has so far achieved mixed results in improving people’s livelihoods around ASF (Ming’ate & Bollig, 2016; Busck-Lumholt & Treue, 2018) and Taita Hills (Hohenthal, 2018; Rülke et al. 2020), as well as in ecological conservation outcomes (Cuadros-Casanova et al. 2018; Bendzko et al. 2019; Schürmann et al. 2020; Teucher et al. 2020). We recorded low awareness on biodiversity for all three study sites, despite the fact that ASF and Taita Hills are listed as global biodiversity hotspots and still hold a large number of endemic endangered plant and animal species (Nzau et al. 2020; Rülke et al. 2020; Nzau et al. 2021a). Logging is ranked as major threat to the forest and was associated with the exclusion of local people, corruption, and pervasive lack of benefit-sharing arrangements (Nzau et al. 2020; 2021a). Generally, men of intermediate education showed higher awareness than women, who are closely associated with place-based knowledge and experiences in the context of local labour migration and marriage patterns (Nzau et al. 2021a; Nzau, 2021).

Income and the level of poverty (land availability) also affects attitudes towards forest conservation. Most of the participants were full-time small-holder farmers, with minimal monthly incomes (< 50 USD). We observed that wealthier households tended to purchase charcoal, firewood, poles, and timber from more impoverished farmers, who in turn sourced these products directly from the forest (in ASF and Taita Hills) or their private land properties (in Kitui County). Consequently, resource overexploitation pressures may be shifted from wealthier to the more impoverished landowners (Stern, 2004; Mills & Waite, 2009; Vyamana, 2009). This scenario is especially evident in Kitui County, where landholdings per household were relatively small (≤ 1 acre) (Nzau et al. 2018) and in the Taita Hills, where landholdings per household are highly fragmented into small distinctive parcels (Hohenthal, 2018; Teucher et al. 2020).

Environmental communication

Radio and TV are the most important media for communicating information to the population. The internet, on the other hand, played a subordinate role. Overall, there was a high spatial bias among educated people, which correlated positively with access to mass media, the internet, and NGOs (Nzau, 2021). Spatial biases have been linked to environmental communication when global environmental concerns are given dominance over immediate problems (Schultz et al. 2014; Nzau et al. 2018). Spatial biases impact conservation action in that when people underestimate the magnitude of environmental problems at their local scales, they are unlikely to implement timely solutions (Gifford et al. 2009; Schultz et al. 2014). In Kitui County and Taita Hills, the highest spatial bias was among part-time farmers and participants with higher incomes which may be explainable by their higher purchasing power (Stern, 2004; Mills & Waite 2009) for consistent access to mass media and the internet as well as circular migration which constantly exposes them to comparative environmental at locally and elsewhere (Nzau et al. 2021a). Full-time farmers notably showed lesser trust for all external environmental information (Nzau et al. 2021a). This trend can be tied to long-term experiences with disenfranchisement (Brockington, 2004; Githiru, 2007; Rülke et al. 2020).

In general, environmental information from governmental- and non-governmental organizations was met with distrust (Nzau et al. 2020; 2021a), while local chiefs were regarded as important sources of environmental information, even though they were hardly trained as environmental experts (Nzau, 2021). This distrust may arise from past alienation experiences with conservation agencies, and creates communication anomalies that derail the success of co-management conservation initiatives (Hohenthal, 2018; Busck-Lumholt & Treue, 2018; Nzau et al. 2020; 2021a). Although the usage of all sources of environmental information was prevalent in Taita Hills, it coincided with a general distrust for all external sources of environmental information, which increased with age (Nzau et al. 2021a). In ASF, the distrust for environmental information from government agencies increased with higher formal education. In contrast, trust for governmental information increased with the education level in Kitui County. Simultaneously, distrust for all external sources of information was pronounced among full-time farmers in Kitui County (Nzau, 2021).

Suggestions for forest protection

Activities to protect the forest differed considerably among the three forest regions. The proposals for forest protection and conservation and the corresponding measures differed among the three regions. For example, reforestation was proposed for the Taita Hills, and more sustainable use of resources was proposed for Kitui County. Sustainable agriculture did not play a central relevance in any of the three regions as a possible measure to conserve nature and the forest. Furthermore, other different concrete solutions were presented, depending on age and education level. People with intermediate to higher formal education levels considered reforestation, and those with higher incomes favoured sustainable extraction of natural resources. These trends can be tied again to increased purchasing powers among the educated people who can negotiate off-farm employment and thereby less reliant on immediate ecosystem services (Stern, 2004; Vyamana, 2009). Other prominent local opinions included the water availability for agriculture, education and awareness, enforcement of environmental law and the co-management of environmental resources (Nzau, 2021). Tree planting was the most common alternative livelihood strategy among people living in Taita Hills, with men likely to engage in it. On the other hand, butterfly farming was common in ASF, irrespective of gender (Gordon & Ayiemba, 2003). The long-term residents surrounding ASF were also highly likely to keep bees (Nzau, 2021). While young people demonstrated the highest willingness to implement good environmental practices, they were less likely to have the resources, especially land rights (Bendzko et al. 2019; Schürmann et al. 2020) and the decision-making authority to release their good intentions (Nzau, 2021). Young people, therefore, held the opinion that off-farm employment would reduce resource extraction pressure from forests which was in parallel to the ideas of alternative income strategies such as butterfly farming and beekeeping that are often advanced by governmental and non-governmental agencies (Nzau et al. 2020; 2021a).

Conclusions

The principles of co-management and Participatory Forest Management (PFM) offer a valuable framework for conserving tropical forests. However, the degree to which these principles can be implemented is dependent on distinct and discreet social-ecological factors that can contribute and reinforce inverse trade-offs and significantly undermine positive conservation outcomes. We found various discrepancies among the three study sites, which needs to be considered when developing and implementing efficient conservation strategies. In the ASF forest, many people live there for less than 20 years; at the same time, the awareness of forest conservation was relatively low there compared to the other two study sites. Forests play a major role against the backdrop of resource use in all three regions, with significant differences in the ecosystem services used in the three different regions. Likewise, the proposals for efficient forest conservation differ: Reforestation is proposed in Taita Hills and Kitui County, whereas off-farm employment plays a major role in ASF. The proposed conservation measures also differed according to age and education level. For environmental education and communication, the internet plays a comparatively minor role. Based on our findings, we argue that the implementation of locally specific conservation action needs to be developed and applied, particularly in countries with very heterogeneous ethnicities and environments. Overall, the lack of transparency and equity in natural resource management overrides positive conservation attitudes, intentions, and willingness with negative implications for governmental and non-governmental conservation experts’ legitimacy and ultimately for the conservation agenda.

Data Availability

All data are provided as electronic appendix.

References

Agrawal A, Chhatre A, Hardin R (2008) Changing Governance of the World’s Forests. Science 320(5882):1460–1462. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1155369

Bendzko T, Chigbu UE, Schopf A, de Vries WT (2019) Consequences of Land Tenure on Biodiversity in Arabuko Sokoke Forest Reserve in Kenya: Towards Responsible Land Management Outcomes. In: Bamutaze Y, Kyamanywa S, Singh BR, Nabanoga G, Lal R (eds) Agriculture and Ecosystem Resilience in Sub Saharan Africa. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12974-3_8

Borrini-Feyerabend G, Farvar T, Nguinguiri JC, Ndangang V (eds) (2007) Co-management of natural resources: Organising, negotiating and learning-by-doing (2., rev. Aufl.). Heidelberg: Kasparek

Brockington D (2004) Community conservation, inequality, and injustice: Myths of power in protected area management. Conserv Soc 2:411–432

Büscher B, Whande W (2007) Whims of the Winds of Time? Emerging Trends in Biodiversity Conservation and Protected Area Management.Conservation and Society, (5),22–43

Busck-Lumholt LM, Treue T (2018) Institutional challenges to the conservation of Arabuko-Sokoke Coastal Forest in Kenya. Int Forestry Rev 20(4):488–505. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554818825240665

Cuadros-Casanova I, Zamora C, Ulrich W, Seibold S, Habel JC (2018) Empty forests: Safeguarding a sinking flagship in a biodiversity hotspot. Biodivers Conserv 27(10):2495–2506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-018-1548-4

Dörnyei Z (2007) Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies. Oxford University Press, Oxford; New York, N.Y

Gifford R, Scannell L, Kormos C, Smolova L, Biel A, Boncu S, Uzzell D (2009) Temporal pessimism and spatial optimism in environmental assessments: An 18-nation study. J Environ Psychol 29(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.06.001

Githiru M (2007) Conservation in Africa: But for whom? Oryx 41(2):119–120. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605307001937

Gordon I, Ayiemba W (2003) Harnessing Butterfly Biodiversity for Improving Livelihoods and Forest Conservation: The Kipepeo Project. J Environ Dev 12(1):82–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496502250439

Habel JC, Teucher M, Ulrich W, Schmitt T (2018) Documenting the chronology of ecosystem health erosion along East African rivers. Remote Sens Ecol Conserv 4(1):34–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/rse2.55

Habel J, Christian, Teucher M, Hornetz B, Jaetzold R, Kimatu JN, Kasili S, Lens L (2015) Real-world complexity of food security and biodiversity conservation. Biodivers Conserv 24(6):1531–1539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-015-0866-z

Hansen AJ, Burns P, Ervin J, Goetz SJ, Hansen M, Venter O, Armenteras D (2020) A policy-driven framework for conserving the best of Earth’s remaining moist tropical forests. Nat Ecol Evol 4(10):1377–1384. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1274-7

Hohenthal J (2018) Local ecological knowledge in deteriorating water catchments: Reconsidering environmental histories and inclusive governance in the Taita Hills, Kenya. Retrieved from http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-2946-8

Jaeger JAG (2000) Landscape division, splitting index, and effective mesh size: New measures of landscape fragmentation. Landscape Ecol 15(2):115–130. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008129329289

Kavousi J, Goudarzi F, Izadi M, Gardner CJ (2020) Conservation needs to evolve to survive in the post-pandemic world. Glob Change Biol 26(9):4651–4653. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15197

Kellert SR, Mehta JM, Ebbin SA, Lichtenfeld LL (2000) Community Natural Resource Management: Promise, Rhetoric, and Reality. Soc Nat Resour 13(8):705–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/089419200750035575

Miles L, Newton AC, DeFries RS, Ravilious C, May I, Blyth S, Gordon JE (2006) A global overview of the conservation status of tropical dry forests. J Biogeogr 33(3):491–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01424.x

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Program) (Ed.). (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: Synthesis. Washington, DC:Island Press

Mills JH, Waite TA (2009) Economic prosperity, biodiversity conservation, and the environmental Kuznets curve. Ecol Econ 68(7):2087–2095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.01.017

Ming’ate FLM, Bollig M (2016) Local Rules and Their Enforcement in the Arabuko-Sokoke Forest Reserve Co-Management Arrangement in Kenya. J East Afr Nat History 105(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.2982/028.105.0102

Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J (2000) Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403(6772):853–858. https://doi.org/10.1038/35002501

Njogu JG, Afrika-Studiecentrum (2004) Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden, &. Community-based conservation in an entitlement perspective: Wildlife and forest biodiversity conservation in Taita, Kenya. Leiden: African Studies Centre. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1887/12921

Nzau JM, Gosling E, Rieckmann M, Shauri H, Habel JC (2020) The illusion of participatory forest management success in nature conservation. Biodivers Conserv 29(6):1923–1936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-01954-2

Nzau JM, Rogers R, Shauri HS, Rieckmann M, Habel JC (2018) Smallholder perceptions and communication gaps shape East African riparian ecosystems. Biodivers Conserv 27(14):3745–3757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-018-1624-9

Riggio J, Jacobson AP, Hijmans RJ, Caro T (2019) How effective are the protected areas of East Africa? Global Ecol Conserv 17:e00573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00573

Rülke J, Rieckmann M, Nzau JM, Teucher M (2020) How Ecocentrism and Anthropocentrism Influence Human–Environment Relationships in a Kenyan Biodiversity Hotspot. Sustainability 12(19):8213. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198213

Schreckenberg K, Luttrell C (2009) Participatory forest management: A route to poverty reduction? Int Forestry Rev 11(2):221–238. https://doi.org/10.1505/ifor.11.2.221

Schultz PW, Milfont TL, Chance RC, Tronu G, Luís S, Ando K, Gouveia VV (2014) Cross-Cultural Evidence for Spatial Bias in Beliefs About the Severity of Environmental Problems. Environ Behav 46(3):267–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512458579

Schürmann A, Kleemann J, Fürst C, Teucher M (2020) Assessing the relationship between land tenure issues and land cover changes around the Arabuko Sokoke Forest in Kenya. Land Use Policy 95:104625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104625

Shepheard-Walwyn E (2014) Culture and conservation in the sacred sites of Coastal Kenya. University of Kent

Steinhart EI (2000) Elephant Hunting in 19th-Century Kenya: Kamba Society and Ecology in Transformation. Int J Afr Hist Stud 33(2):335. https://doi.org/10.2307/220652

Stern DI (2004) The Rise and Fall of the Environmental Kuznets Curve. World Dev 32(8):1419–1439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.03.004

Teucher M, Schmitt CB, Wiese A, Apfelbeck B, Maghenda M, Pellikka P, Habel JC (2020) Behind the fog: Forest degradation despite logging bans in an East African cloud forest. Global Ecol Conserv 22:e01024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01024

Vyamana VG (2009) Participatory forest management in the Eastern Arc Mountains of Tanzania: Who benefits? Int Forestry Rev 11(2):239–253. https://doi.org/10.1505/ifor.11.2.239

Acknowledgements

We thank the local populations and representatives of governmental and non-governmental organizations of the three study sites for participating in our study. We are grateful to Lozi Maranga for the collection of data in the field. We thank Mike Teucher for producing Fig. 1. The German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) granted a PhD fellowship to JMN. We are grateful for two very valuable and critical reviews about a draft version of our manuscript.

Funding

Funding is reported in the Acknowledgement section.

Open access funding provided by Paris Lodron University of Salzburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JMN and JCH designed the study, JMN performed data collection, WU run analyses, all contributed while data interpretation and writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is not conflict of interest.

Animal Research

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent to Publish

All approved to publish this data and article.

Plant Reproducibility

Not applicable.

Clinical Trials Registration

Not applicable.

Additional information

Communicated by Dirk Sven Schmeller.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nzau, J.M., Ulrich, W., Rieckmann, M. et al. The need for local-adjusted Participatory Forest Management in biodiversity hotspots. Biodivers Conserv 31, 1313–1328 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-022-02393-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-022-02393-x