Abstract

General public inclusion in nature conservation is crucial to accomplish wildlife species recovery. Mammal and bird species usually receive most of the research and general public attention, leaving aside other taxa species. It is necessary to obtain general public support towards other taxa species by emphasizing ecological attributes. Here we test if the disclosure of the threatened and endemic status of amphibians, fish, and invertebrates, could increase general public support. Additionally, we wanted to identify if the threatened and endemic status could implicate a difference in support. Interviews (N: 359) were conducted among the general public in Valdivia, Chile, to elicit the support, allocation of a fictional fixed amount of conservation funds (WTS), towards native wildlife species. The species were two mammals, and four bird species, none threatened nor endemic, and two amphibians, one fish, and three invertebrates, all threatened and endemic. The WTS was derived on two occasions for each participant. Firstly presenting colorful pictures with the name of the species and, secondly, adding the threatened and endemic status in two separate treatments. Results indicated mammal and bird species with significantly higher WTS when pictures and names were provided. The main driver was a misperception of the threatened status of these species. When the threatened and endemic status was disclosed, the WTS significantly shift towards the amphibians, fish, and invertebrates. No difference in the WTS was spotted between the threatened or endemic status. As our results indicate participants associate charismatic species (mammal and birds) with threatened status. We encourage nature conservation entities to promote a broader spectrum of wildlife species by emphasizing conservation needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Large-sized vertebrates species, like mammals and birds, have been the focus of research studies over non-mammalian and bird species as reptiles, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates species (Donaldson et al. 2017), possibly owing to low public preferences for this last group of species (Jarić et al. 2019). Additionally, the general public tends to support mammal and bird species over other taxa (Albert et al. 2018; Colléony et al. 2017; Kellert 1996; Knight 2008; Liordos et al. 2017; Tisdell et al. 2006; Tisdell and Wilson 2006). As a result, mammal and bird species have been widely used in marketing and fundraising strategies developed by conservation NGOs (Albert et al. 2018), like the Giant Panda by the WWF and the polar bear by Green Peace U.S.A. Also, in consumer products, like U.S.A. conservation and nature magazines; mammal and bird species usually are on their front covers (Clucas et al. 2008).

Aesthetic and negativistic attitudes of the general public could explain, to some extent, non-mammalian and bird species being ignored in research and general public attention. Aesthetic and negativistic attitudes have been described as the physical appeal and beauty of wildlife and as fear, aversion, and alienation from wildlife, respectively (Kellert 1996). Liordos et al. (2017) and Knight (2008) had quantified these concepts to predict the main drivers of support by the general public towards wildlife species. Their results revealed that mammal and bird species overall received a high aesthetic score and low negativistic value, being the opposite for non-mammalian and bird species. Similarly, Albert et al. (2018) identified that the general public associated large-sized vertebrates with charismatic species, usually perceived with high aesthetic value (Knight 2008; Liordos et al. 2017). A potential side effect of this is that non-mammalian and bird species remain anonymous to the general public.

The threatened status is an attribute generally used to increase general public support towards wildlife species. Information disclosure of wildlife species promotes an increase in support independently of the aesthetic or negativistic attitudes of the general public towards certain species (Tisdell 2006; Tisdell et al. 2007; Tisdell and Wilson 2004, 2006). Additionally, information disclosure induces an equal distribution of support, e.g., allocation of a fictional fixed amount of conservation funds, among species independent of their physical appearance (Tisdell and Wilson 2006). Specifically, the threatened status increases general public support towards wildlife species with a low aesthetic value (Tisdell et al. 2006, 2007; Tkac 1998). However, the endemic status of a species has not been empirically assessed as an ecological attribute that increases general public support or contrasted with the threatened status.

The “Carlos Anwandter” Nature Sanctuary (CANS) is a protected wetland located in the south of Chile, surrounding the city of Valdivia. Nowadays, due to the increasing loss of human-nature interactions (Kellert 1996; Soga and Gaston 2016), different strategies to “reconnect” people with nature have been conducted. The usage of digital social media by environmental institutions has been a strategy to increase awareness and support of wildlife species among the general public (Jarić et al. 2019; Kidd et al. 2018). A Chilean local NGO, in Valdivia, has been promoting native wildlife species through their social media platforms. Their species selection criteria are mostly based on threatened or endemic status rather than charisma. As the endemic rate of wildlife species in Chile is globally one of the highest (Mittermeier et al. 2011), we considered the study area appropriate to identify if the disclosure of the threatened and endemic status of wildlife species could raise a difference on support by the general public. Consequently, a higher promotion of reptiles, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates species, could be translated into pecuniary and non-pecuniary resources donated by the general public to promote conservation activities for these taxa species (Veríssimo et al. 2017).

To elicit general public support towards wildlife species, Stated Preferences Techniques to value non-market goods, specifically the Contingent Valuation Method (CVM), have been used. This involves directly asking people how much they would be willing to pay or accept (WTP/WTA) for a specific wildlife species to increase or decrease in a certain time and area (Richardson and Loomis 2009; Tisdell and Wilson 2004). A variation of the WTP has been the allocation of a fixed amount of money/conservation fund, also coined as “fixed pie” or “constant-sum game”, to be distributed among wildlife species or ecological species attributes (DeKay and McClelland 1996; Gunnthorsdottir 2001; Meuser et al. 2009; Samples et al. 1986; Tisdell and Wilson 2004, 2006; Tkac 1998). The “constant sum game”, from now on referred as willingness to support (WTS), has proven to be effective in identifying changes in support, e.g., money allocation, among wildlife species depending on an increase or correction of knowledge about the species (Tisdell et al. 2007; Tisdell and Wilson 2006).

Studies that had investigated the influence of information disclosure on the WTS wildlife species by the general public, have been done through methods not recommended in developing countries. These studies imply a longitudinal design (Newing 2010), capable of tracking changes over time. Researchers who had conducted these studies had collected their data mainly in developed countries by a mixture between workshop attendance and post (Tisdell et al. 2006; Tisdell and Wilson 2004, 2006). The guidelines to develop Contingent Valuation Methods in developing countries, “Applications of the contingent valuation method in developing countries” (Alberini and Cooper 2000), recommend these studies should be developed through face-to-face interviews. Likewise, Bandara and Tisdell (2005), justified face-to-face interviews in Sri Lanka, because telephone or post approaches could be biased towards certain socio-demographic groups of the study area. Therefore we needed to adjust previous methodologies used to identify changes of support towards wildlife species, after the provision of information, in a single face-to-face interview.

Our study differs from previous research that had assessed the effect of information disclosure on the WTS wildlife species by the general public to some extent. The present study was conducted among the general public, from a major city, through an experimental design, i.e., with a control group. Previous studies that had considered a control group have been conducted among university students using wildlife species that do not cohabit with the interviewees (Samples et al. 1986; Tkac 1998). On the other hand, those conducted among the general public with wildlife species cohabitating with the participants and current threatened status had not considered a control group in the experimental design (Tisdell et al. 2005, 2006, 2007; Tisdell and Wilson 2004, 2006).

The aim of this study was, firstly, to test if information disclosure of the threatened and endemic status of wildlife species perceived with a low aesthetic value could influence the WTS. Secondly, to identify if a difference in the WTS could occur if the threatened or endemic status of the same wildlife species is disclosed. Thirdly, assess how the drivers behave, before and after the threatened, and endemic status is presented to the participants. Finally, assess the survey administration method applied in terms of suitability and effectiveness.

Methodology

Study area

The study area corresponded to the City of Valdivia, located approximately 900 km south of Santiago, the capital of Chile. Valdivia has an area of 1016 km2 and 166,080 inhabitants. The male and female proportion corresponds to 48.38% and 51.62%, respectively. The main economic activities, in descending order, correspond to retail, real estate, construction, transportation and communication, agriculture, and livestock—forestry activities.

The CANS, located in the River “Cruces” Wetland (RCW), has a surface of 4877 hectares. Much of the RCW surrounds the City of Valdivia. The National Forest Corporation has described approximately 172 wildlife vertebrates species present in the area, with a high level of endemism and a high percentage of them in a threatened status since the NSCA is located in one of the 36 Biodiversity Hotspots, “Chilean Winter Rainfall and Valdivian Forest” (Mittermeier et al. 2011).

Survey design

A quantitative questionnaire for conducting interviews was chosen to test the correlation and direction between variables. The questionnaire consisted of the following sections: (i) Influence of information disclosure on the WTS, (ii) drivers of WTS: aesthetic and negativistic attitudes; general and specific knowledge of the species, and (iii) socio-demographic characteristics. These sections are described below (An English translation of the questionnaire is provided as Supplementary material, Appendix N° 1).

Influence of information disclosure on the WTS wildlife species by the general public

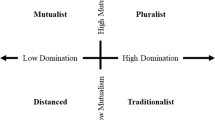

The WTS was assessed as the allocation of conservation funds, a fixed hypothetical amount of money to measure changes in support after disclosing ecological attributes of wildlife species through the use of labels (Tisdell and Wilson 2004, 2006). Twelve simulated bills (each bill with a value of 1,000.000 CLP) were given to the participants. Additionally, it was told to the participants that all bills should be distributed among the species, and the money would be delivered to environmental organizations to conduct conservation activities for the selected species. Therefore, a high allocation of money for a species could be translated into more possibilities to maintain or increase that species population. The WTS was registered on two occasions for each participant: (i) first WTS: presenting colorful pictures and their names, and afterward, (ii) second WTS, disclosing ecological attributes of the wildlife species (Fig. 1). Once the participant allocates the money among the species (I-$), it was registered by the interviewer. Later, the participants were randomly placed in one of the three treatments. One-third of the sample the threatened status was disclosed, the other third the endemic status, and the last third the taxonomic group of the wildlife species, this last as a control group. Finally, the participants were asked if, with the new information, they would like to reallocate the money among the species. The final amounts allocated were registered for each treatment (TH-$, EM-$, and TAXA-$).

Conceptual model of the study where the WTS towards twelve wildlife species was derived, left, providing colorful pictures and names, and afterward, right, disclosing ecological attributes in three different treatments: i. threatened status, ii. endemic status, and iii. the taxa of the species, this last as a control group

The design allowed us to test the following hypotheses:

H1

Without information on the threatened and endemic status, mammal and bird species will receive a higher WTS compared to non-mammalian and bird species

H2

After the disclosure of the threatened and endemic status, the WTS will increase towards species in a threatened and endemic status

H3

It will make a difference in the WTS for the same wildlife species whether the threatened or endemic status is disclosed.

Species selection criteria

The species to be included in the study had to satisfy two criteria. The first half should be mammal and bird species, which usually have public support due to their charisma (Albert et al. 2018), and the other half not-mammalian and bird species usually receiving less support from the general public (Knight 2008; Liordos et al. 2017). This last half should be in a threatened and endemic status and the opposite for the mammal and bird species. To avoid confusion to the participants, if the species were in any of the IUCN threatened categories (critically endangered, endangered and vulnerable), they were told that the species was in a threatened status. Different source to identify the threatened and endemic status of each species was consulted, including the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN 2020) and the national inventory of wildlife species of Chile (Ministry of Environment 2020). The species included were two mammals, four birds, two amphibians, one fish, and three invertebrates (Table 1).

Drivers of WTS

A set of independent variables was taken from similar studies to predict the WTS towards the wildlife species by the general public. Authors have identified values to explain the types of relations or connections between human-kind and the natural world (Kellert 1996; Kellert and Wilson 1995). Some researchers have taken these values to predict the main drivers of support towards wildlife species, as aesthetic and negativistic attitudes (Knight 2008; Liordos et al. 2017; Veríssimo et al. 2009). Aesthetic attitude (ATH) has been defined as the tendency to place primary focus on the larger, more colourful, mobile, and diurnal species, e.g., mammals and birds (Kellert and Wilson 1995). Negativistic attitude (NEG) is related to hostility and negative feelings as aversion, fear, or dislike. To assess these attitudes, questions and wording were taken from Liordos et al. (2017). To measure ATH, participants were asked: “could you please tell me what your initial reaction to each of the animals shown in the photographs is?” and for NEG they were asked: “how relaxed or afraid would you feel around each of the animals shown in the photographs in an encounter in the wilderness?” The answers were measured by a Likert-like scale ranging from very ugly (− 2) to very attractive (2) and very relaxed (− 2) to very afraid (2), respectively.

Additionally (before the treatments), the knowledge (perception) of the threatened and endemic status of each of the species was asked (KLDG-TH and KLDG-EM), as well as the general knowledge (KLDG-GNRL). Wilson and Tisdell (2005) assessed a higher allocation of a hypothetical fixed amount of money towards species that were better known and common among the citizens of Brisbane, Australia. For threatened and endemic status, a brief definition was given of both concepts before the participant could answer. Afterward, each participant was asked: “According to your knowledge or perception, could you please tell me which species is threatened/endemic?” The answers were: (i) In a threatened / endemic status or ii. not. To measure the general knowledge of the species, participants were asked: “Could you please tell me how much information do you have of each of the species?” E.g. where does it live, what does eat, the size of the population? The answer was measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from very little information (− 2) to adequate information (2).

To assess socio-demographic characteristics, participants were asked to indicate their gender, age, education level, and monthly income (categories of each variable are presented in Appendix N° 1).

Sampling protocol

The sample units were citizens of Valdivia, as is recommended when the objective is to study attitudes between people and some natural environment components (Colléony et al. 2017; Liordos et al. 2017; Veríssimo et al. 2009). The minimum age to be included in the survey was sixteen years old. The questionnaire was pre-tested by the authors, to test the wording and the functionality of the materials. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with the citizens of Valdivia in public places. The survey was applied during March and April 2019, by three trained university students (interviewers), with the supervision of the first author. A simple random method was applied to obtain a representative sample of the population of Valdivia. Every fifth potential participant to be included in the data set was asked if he or she would be interested in participating in an interview with an average duration of 20 min. To increase the response rate, each person was told that after completing the questionnaire, a lottery ticket would be given for participation in a voucher of 50,000 CLP (approximately 55 €), to be used at a local grocery store. After receiving consent from the participant, ethical clearance was provided, explaining the context, purpose, and possible outcomes of the study and ensuring that her or his anonymity was guaranteed.

Analysis

Two groups of species were constituted to conduct the data analysis and test the stated hypothesis (except for the regressions), mammalian and bird species, and non-mammalian and bird species (Table 1). The overage values for each group of species was calculated as the sum of the money allocation in each of the six species (I-$) divided by sample size (n: 359). To identify significant correlations or differences of (i) WTS and the taxonomic group of the wildlife species (TAXA; mammal and bird species: 1, non-mammalian and bird species: 0), before and after disclosing ecological attributes; (ii) WTS only providing colorful pictures and their names, and each treatment; and (iii) between the treatments, different statistical tests were conducted. For the first, a Spearman’s correlation coefficient was performed between the variables I-$ and TAXA. For the second, a Wilcoxon signed-ranked test, and for the last, a Kruskal–Wallis test with a Dunn’s post hoc test with a Bonferroni adjustment to assess differences within the treatments.

To predict the drivers of support towards the wildlife species, Binary Logistic Regressions were conducted. All the species assessed by each participant were included in the regression, not been grouped by taxa. The variables assessed each time for each species were included as independent: ATH, NEG, KLDG-TH, KLDG-EM, KLDG-GNRL, and TAXA. The dependent variables, I-$, TH-$, EM-$, and TAXA-$, were significant to the Shapiro–Wilk test, been transformed into dichotomous variables: I-E$, TH-E$, EM-E$, and TAXA-E$, respectively. The variable I-E$ was included as an independent variable in the regressions for threatened status and endemic status treatment. In the case of the taxonomic group treatment, I-E$ was not included to avoid multicollinearity. The socio-demographic variables were left aside from the regressions since they fall away from the scope of our hypothesis. From the regressions presented in Table 2, when the socio-demographic were included, for the above regression (before information disclosure), only age was a negative predictor, and for the treatments, only for the threatened status treatment, one variable was significant, being gender as negative predictor. The interpretation of the first would be, younger participants are willing to support a higher diversity of species than older participants. For the second would be female participants support a wider variety of wildlife species when the threatened status is disclosed. Therefore to maintain the focus of our hypothesis, the socio-demographic variables were not included in the results.

Finally, all statistical analysis was performed using the software SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp 2019) for Windows® platform.

Results

Questionnaire response and socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 359 questionnaires were completed with 211 refusals, yielding a response rate of 59%. The sample size for the treatments, threatened status, endemic status, and taxonomic group were 138, 123, and 94, respectively. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 3. The gender proportion is constituted by 50.1% females and 47.9% males. The most common age range was 21–30 years (35.9%). The highest percentage of education corresponds to complete University or Technical degree (43.7%), and the highest percentage of monthly income is none (18.7%), probably due to the high percentage of students in the sample.

WTS presenting colorful pictures and names of the wildlife species

The overage WTS presenting colorful pictures and the names of the wildlife species were 1,466.015 CLP for mammal and bird species and 531.657 CLP for the amphibians, fish, and invertebrates species (Table 4). The results of the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient identify a positive correlation between the variables I-$ and TAXA (rs(4296) = 0.511, p < 0.001). Additionally, based on the binary logistic regression (Table 2) the Odds Ratio of the variable TAXA indicates 4697 more likely a mammal or bird species to be supported instead of an amphibian, fish, or invertebrate species.

Influence of information disclosure on the WTS wildlife species

For the threatened status and endemic status treatments, a negative correlation was found between the variables TAXA and, TH-$ and EM-$, rs(1657) = − 0.466, p < 0.001 and rs(1476) = − 0.466, p < 0.001, respectively. For the taxonomic group treatment, a positive correlation between the variables TAXA and TAXA-$ was spotted, rs(1128) = 0.302, p < 0.001. These results indicate a shift of the WTS towards amphibians, fish, and invertebrates species when the threatened and endemic status was disclosed. For the taxonomic group treatment (mentioning the taxa of each species) the WTS did not shift, and the mammal and bird species still had a higher WTS. Additionally, the Wilcoxon Ranked Test results identify significant differences between the variable I-$ and all treatments (Table 5).

Differences between the threatened and endemic status effect on the WTS wildlife species

The Kruskall–Wallis test shows a statistically significant difference in the WTS between the treatments, both for mammal and bird species and amphibians, fish, and invertebrates species (Table 6). The pairwise comparison identified a statistically significant difference between the control group (taxonomic group) and both treatments, i.e., threatened and endemic status. Contrarily no statistically significant difference between the threatened and endemic treatment was spotted.

Drivers of the WTS before and after disclosing the threatened and endemic status of the wildlife species

The WTS before disclosing the threatened and endemic status of the species had as statistically significant positive predictors the following variables: ATH, KLDG-TH, KLDG-EM, and TAXA. The variables NEG and KLDG-GNRL were negative predictors. After disclosing the threatened and endemic status, the significant positive predictors for both groups were: I-ES, ATH, and KLDG-EM, and negative predictors were KLDG-GNRL and TAXA. The significant positive predictors for the taxonomic group treatment were: ATH, KLDG-TH, KLDG-EM, and TAXA, and negative predictors were NEG and TAXA (Table 2).

Discussion

Three main results, according to our hypotheses, can be derived from the present study: Firstly, mammal and bird species received a higher WTS than the amphibians, fish, and invertebrates species when only pictures and their names were presented, accepting H1. Secondly, after the provision of the threatened and endemic status of the species, there was a significant shift of the WTS from mammal and bird species towards amphibians, fish, and invertebrates species, accepting H2. Thirdly, there was no difference if the participant was informed that a wildlife species is threatened or endemic to promote support among the general public, rejecting H3. Additionally, the method used successfully tested the proposed hypothesis through a single face-to-face interview. The discussion section will be structure as follow. First, our results will be contrasted with previous findings; secondly, the method used will be commented.

WTS presenting colorful pictures and names of the wildlife species

Mammal and bird species, overall, received a higher WTS than the other taxa species included in the study when only colorful pictures and the names were presented to the participants. All the variables included in the regression (Table 2) were either significant positive predictors: ATH, KLDG-T, KLDG-EM, KLDG-GNRL and TAXA, or significantly negative NEG. It has already been assessed that the general public intrinsically will support large-sized vertebrates, particularly mammal and bird species, over other taxa species (Albert et al. 2018; Liordos et al. 2017). What stands out from the present study (not been yet empirically reported) is the perceived threatened and endemic status and aesthetic value as predictors of the WTS. From the sample, 60% of the participants perceived as threatened the mammal and bird species, and only 30% for the amphibians, fish, and invertebrates species (Table 4). Contrary, according to the Red List Index (The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019), overall, non-mammalian and bird species need more conservation efforts, a situation also described for Chile (Giglio 2019). It is possible that the general public associates mammal and bird species as the taxa with more conservation priorities, among others. If this is the case, it would be necessary to continue studying this phenomenon to develop corrective measures to overcome this situation.

Influence of information disclosure on the WTS wildlife species

The results indicate that information disclosure, regardless of the type, has a significant effect on the WTS for wildlife species perceived with low aesthetic value, such as amphibians, fish, and invertebrates species. However, the threatened and endemic status has a major influence. For all treatments (i.e., threatened status, endemic status, and taxonomic group of the wildlife species), the WTS shift towards the amphibians, fish, and invertebrates species when the information was disclosed (Table 5). Similar results were obtained by Samples et al. (1986). He measured information effect on the support towards a wildlife species among university students with a control group. WTP was found to be significantly higher after information was disclosed regarding the species threatened status. In the case of the threatened and endemic treatments, the variables behave in the same way: positive predictors, IE-$, ATH, KLDG-EM, KLDG-GNRL, and negative TAXA. The variable IE-$ indicates when information was disclosed to the participants; in most cases, the reallocation of money among the species was not entirely different, leaving some of the money on the species selected prior to information disclosure. This last could also explain the positive significance of the variable ATH for both treatments. Despite non-mammals and bird species overall were perceived as ugly species (Table 4), and for the threatened status and endemic status treatments, non-mammals and bird species received overall a higher WTS (Table 4), still, the variable ATH was a positive predictor of support (Table 2). The variable KLDG-EM, opposed to KLDG-TH, remained significant, possibly due to the common name of the two amphibians, “Chilean Toad” and “Mehuín Frog”, easily assessed as endemic by the participants due to their common names representing localities in Chile. The primary purpose of the taxonomic group treatment (control group) was to identify the effect of highlighting the amphibians, fish, and invertebrates species with specific ecological characteristics. In the experiment, it was assumed that indicating to which taxonomic group each species belongs would not be relevant information to reallocate the money by the participants. For this last treatment, the predictor variables behave in the same way before information disclosure, except for KLDG-GNRL, not being significant (Table 2). To our knowledge, no studies had tested the effect of information disclosure on the WTS wildlife species by the general public in developing countries and South America. Our findings are congruent with the available literature on the topic, evidencing a shift on the WTS among the species towards those with conservation priorities (Samples et al. 1986; Tkac 1998; Tisdell 2006; Tisdell & Wilson 2004, 2006; Tisdell et al. 2007). Additionally, our results suggest that the type of information delivered can generate a higher or lower WTS. In this case, the threatened and endemic status of the species produced a higher WTS than mentioning the taxonomic group of each species (Samples 1986; Tkac 1998; Tisdell & Wilson 2004; 2006).

Differences between the threatened and endemic status effect on the WTS wildlife species

Disclosing the threatened or endemic status of the same wildlife species to the participants does not imply a difference in the WTS. Based on the fact that the study area is located in one of the 25 hotspots, characterized by “…exceptional concentration of endemic species…” (Mittermeier et al. 2011), we expected the general public could empathize with this ecological attribute to a higher extent than the threatened status, but our results indicate the contrary (Table 4). Into which extend general public empathize or support the endemic status of wildlife species over other attributes, could be context-dependent as different researchers have found contrast results. A study conducted by (Garnett et al. 2018b) indicates that Australian public will support bird species conservation activities independently of their taxonomic distinctiveness. Conversely, some authors have identified that among a series of ecological attributes, including endemism status, this was prioritized among the survey participants (Shapiro et al. 2016; Veríssimo et al. 2009). The complexity of the information should be considered when the general public is asked to manage this specific type of information. For example, an assessment conducted among the citizens of Brisbane, Australia, estimated that few participants managed basic knowledge of ecological features of well-known mammal species (Tisdell et al. 2007; Tisdell and Wilson 2004, 2006). Furthermore, according to Courchamp et al. (2018) the number of correct answers given of the threatened status of the ten most cherished species was infrequent among science university students. Even so, the results of the present study and those cited evidence a disconnection between relative general knowledge managed by researchers and conservationists, and the general public.

Methodological approach

The method used was an effective way to measure the effect of information disclosure on the support towards wildlife species through a single face-to-face interview in public areas, besides obtain a representative sample of the citizens of a major city. Two main points will be discussed regarding the method used. First, a comparison of the results with similar methods but different experimental settings. Secondly, an interpretation of the relation between the perceived threatened status of the wildlife species and the WTS previous information disclosure.

Studies measuring the effect of information disclosure on the WTS towards wildlife species can be categorized into two groups based on the validity of the research design (Newing 2010). One group conducted among university students with a control group and wildlife species that do not cohabit with the interviewed, presenting a high “internal validity”. The other group, conducted among the general public with wildlife species that cohabit with them, without a control group, with a high “context validity”. From the first group, Samples et al. (1986), included two experimental groups to identify differences in the WTP for the conservation of a whale species before and after a video of the species was presented. A control group was included, showing an unrelated whale video (“The Sixty Second Spot: The Making of a Television Commercial”). The results indicated an increase on the WTP for both groups, but the control was lower. Similarly, Tkac (1998) used two groups of students from different university fields, economic and wildlife-related careers. For the economic group, a significant change in the WTP was identified but not for the wildlife group. This was explained partly due to the high previous knowledge of the wildlife group. In the other research design context conducted among the general public by Tisdell and collaborators (Tisdell et al. 2007; Tisdell and Wilson 2004, 2006), the effect of information disclosure among Brisbane citizens was assessed. In the experiment, 24 wildlife species of different taxa with different conservation status were included. Overall, the results identified a change in the WTS towards particular wildlife species after information was disclosed. Our experimental setting included a control group and was applied among the general public, giving to some extent, "internal" and "context" validity to the results. This confirms the results of previous findings giving more validity to the research identifying the effect of information disclosure to increase the support towards certain wildlife species.

As the study was conducted through a face-to-face interview, the social desirability bias could have a major effect on the relationship between mammal and species and being perceived in a threatened status by the participants. Specifically in CVM, the social desirability bias generally is reflected in higher WTS, or WTP, stated by the participants than they would genuinely give, compared to, e.g., self-administered questionnaires (Leggett et al. 2003). In the present study, we used allocation of a fixed amount of money, therefore the bias could not be translated into a higher or lower WTS, or WTP. Instead, a social desirability bias related to give correct answers regarding the threatened and endemic status of the species could have happened. To illustrate this, and for simplicity, we will only refer to the threatened status. At the beginning of the interview, the participant was told that the money allocated to each species will be used to promote conservation activities to “…increase or maintain the selected species population…”. It is likely that the participants have allocated the money in those species with a high aesthetic value, such as mammal and bird species (Knight 2008; Liordos et al. 2017) or were driven by a resemblance pattern, i.e. phylogenetic closeness or principle of similarity to humans (Gunnthorsdottir 2001; Kellert 1996). Afterward, the threatened status of the species was asked and it could be that the participants (and recalling the purpose of the interview) indicate those species as threatened based on their initial money allocation.

Despite these limitations, the methods turn out to be suitable and effective. It could be replicated in similar socio-demographic contexts, where currently there is a lack of studies measuring the support towards wildlife species and information effects for the general public.

New research question and conservation and management implications

An unexpected result from the study, even a surprise, indicates that the general public wrongly perceives mammals and bird species with higher conservation needs, and the WTS could be due to that misperception. If we leave aside the possible effect of the social desirability bias in our study, the following research question stands opened: does the general public perceive mammals and birds more threatened than other taxa species? The correlation between general public support and mammal and bird species over other taxa has been empirically assessed (Albert et al. 2018; Gunnthorsdottir 2001; Knight 2008; Tisdell et al. 2006). But, to the best of our knowledge, the correlation between general public perceiving mammal and bird species, comparatively, in a higher percentage of threatened status than other taxa species, not. The implication of this misperception could be beyond our interpretations, e.g. it has been described that research or social attention towards certain species or taxa could be at the expend of others (Douglas and Winkel 2014). We encourage researchers to continue investigating this topic, firstly to answer the question, and secondly to take the necessary measures.

Based on our results and considering that non-mammalian and bird species currently face the following situations: they are (i) in a higher extinction rate than mammals and bird species, (ii) are left aside of the general public by environmental institutions, due to their low perceived charisma, thus the chances that the general public could know or manage basic information of it is unlikely, and (iii) due to their generally low aesthetic value, they will not be intrinsically supported by the general public. As community-based conservation is crucial to achieve natural resources management and conservation (Berkes 2004; Brooks et al. 2013; McKinley et al. 2017), the use of a broader range of taxa species by conservation practitioners might be a strategy to deliver an objective spectrum and state of all wildlife species to the general public (Bowen-Jones and Entwistle 2002; Entwistle 2000; Garnett et al. 2018a; Tisdell et al. 2006; Troudet et al. 2017). For example, conservation practitioners could use species not based on their aesthetic value but on relevant ecological attributes such as the threatened and endemic status (Brambilla et al. 2013).

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alberini A, Cooper J (2000) Applications of the contingent valuation method in developing countries: a survey. Food & Agriculture Org

Albert C, Luque GM, Courchamp F (2018) The twenty most charismatic species. PLoS ONE 13:e0199149. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199149

Bandara R, Tisdell C (2005) Changing abundance of elephants and willingness to pay for their conservation. J Environ Manag 76:47–59

Berkes F (2004) Rethinking community-based conservation. Conserv Biol 18:621–630

Bowen-Jones E, Entwistle A (2002) Identifying appropriate flagship species: the importance of culture and local contexts. Oryx 36:189–195

Brambilla M, Gustin M, Celada C (2013) Species appeal predicts conservation status. Biol Cons 160:209–213

Brooks J, Waylen KA, Mulder MB (2013) Assessing community-based conservation projects: a systematic review and multilevel analysis of attitudinal, behavioral, ecological, and economic outcomes. Environ Evid 2:2

Clucas B, McHugh K, Caro T (2008) Flagship species on covers of US conservation and nature magazines. Biodivers Conserv 17:1517

Colléony A, Clayton S, Couvet D, Saint Jalme M, Prévot AC (2017) Human preferences for species conservation: animal charisma trumps endangered status. Biol Conserv 206:263–269

Courchamp F, Jaric I, Albert C, Meinard Y, Ripple WJ, Chapron G (2018) The paradoxical extinction of the most charismatic animals. PLoS Biol 16:e2003997

DeKay ML, McClelland GH (1996) Probability and utility of endangered species preservation programs. J Exp Psychol Appl 2:60

Donaldson MR, Burnett NJ, Braun DC, Suski CD, Hinch SG, Cooke SJ, Kerr JT (2017) Taxonomic bias and international biodiversity conservation research. FACETS 1:105–113. https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2016-0011

Douglas LR, Winkel G (2014) The flipside of the flagship. Biodivers Conserv 23:979–997

Entwistle A (2000) Flagships for the future? Oryx 34:239–240

Garnett ST, Ainsworth GB, Zander KK (2018a) Are we choosing the right flagships? The bird species and traits Australians find most attractive. PLoS ONE 13:e0199253

Garnett ST, Zander KK, Hagerman S, Satterfield TA, Meyerhoff J (2018b) Social preferences for adaptation measures to conserve Australian birds threatened by climate change. Oryx 52:325–335

Giglio (2019): Country Report 2018, State of the Environment Chile. Public Policy Analysis Center, Institute of Public Affairs, University of Chile, Santiago

Gunnthorsdottir A (2001) Physical attractiveness of an animal species as a decision factor for its preservation. Anthrozoös 14:204–215

Corp IBM (2019) IBM SPSS statistics for windows. Armonk, NY

IUCN 2020: (International Union for the Conservation of Nature). 2020. IUCN red list of threatened species. Version 2019–3. IUCN, Glands, Switzerland. Available form www.iucnredlist.org (accessed Mar 2020)

Jarić I, Correia RA, Roberts DL, Gessner J, Meinard Y, Courchamp F (2019) On the overlap between scientific and societal taxonomic attentions—insights for conservation. Sci Total Environ 648:772–778

Kellert SH (1996) The value of life: biological diversity and human society. Island, Washington, D.C.

Kellert SR, Wilson EO (1995) The biophilia hypothesis. Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Kidd LR, Gregg EA, Bekessy SA, Robinson JA, Garrard GE (2018) Tweeting for their lives: visibility of threatened species on twitter. J Nat Conserv 46:106–109

Knight AJ (2008) “Bats, snakes and spiders, Oh my!” how aesthetic and negativistic attitudes, and other concepts predict support for species protection. J Environ Psychol 28:94–103

Leggett CG, Kleckner NS, Boyle KJ, Dufield JW, Mitchell RC (2003) Social desirability bias in contingent valuation surveys administered through in-person interviews. Land Econ 79:561–575

Liordos V, Kontsiotis VJ, Anastasiadou M, Karavasias E (2017) Effects of attitudes and demography on public support for endangered species conservation. Sci Total Environ 595:25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.241

McKinley DC, Miller-Rushing AJ, Ballard HL, Bonney R, Brown H, Cook-Patton SC, Evans DM, French RA, Parrish JK, Phillips TB (2017) Citizen science can improve conservation science, natural resource management, and environmental protection. Biol Conserv 208:15–28

Meuser E, Harshaw HW, Mooers AØ (2009) Public preference for endemism over other conservation-related species attributes. Conserv Biol 23:1041–1046

Ministry of Environment 2020: National inventory of species of Chile. Ministry of Environment, Santiago. Available from especies.mma.gob.cl/CNMWeb/Web/WebCiudadana/default.aspx (accessed Mar 2020)

Mittermeier RA, Turner WR, Larsen FW, Brooks TM, Gascon C (2011) Global biodiversity conservation: the critical role of hotspots. In: Zachos FE, Habel JC (eds) Biodiversity hotspots. Springer, Berlin, pp 3–22

Newing H (2010) Conducting research in conservation: social science methods and practice. Routledge, London

Richardson L, Loomis J (2009) The total economic value of threatened, endangered and rare species: an updated meta-analysis. Ecol Econ 68:1535–1548

Samples KC, Dixon JA, Gowen MM (1986) Information disclosure and endangered species valuation. Land Econ 62:306–312

Shapiro HG, Erickson KA, Peterson MN, Frew KN, Stevenson KT, Langerhans RB (2016) Which species to conserve: evaluating children’s species-based conservation priorities. Biodivers Conserv 25:539–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1067-0

Soga M, Gaston KJ (2016) Extinction of experience: the loss of human-nature interactions. Front Ecol Environ 14:94–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1225

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (2019) Red List Index. https://www.iucnredlist.org/assessment/red-list-index. Accessed 13 Dec 2019

Tisdell C (2006) Knowledge about a species’ conservation status and funding for its preservation: analysis. Ecol Model 198:515–519

Tisdell C, Nantha HS, Wilson C (2007) Endangerment and likeability of wildlife species: how important are they for payments proposed for conservation? Ecol Econ 60:627–633

Tisdell C, Wilson C (2004) The public’s knowledge of and support for conservation of Australia’s tree-kangaroos and other animals. Biodivers Conserv 13:2339–2359

Tisdell C, Wilson C, Nantha HS (2005) Association of public support for survival of wildlife species with their likeability. Anthrozoös 18:160–174. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279305785594216

Tisdell C, Wilson C (2006) Information, wildlife valuation, conservation: experiments and policy. Contemp Econ Policy 24:144–159. https://doi.org/10.1093/cep/byj014

Tisdell C, Wilson C, Nantha HS (2006) Public choice of species for the ‘Ark’: phylogenetic similarity and preferred wildlife species for survival. J Nat Conserv 14:97–105

Tkac J (1998) Award-winning undergraduate paper: the effects of information on willingness-to-pay values of endangered species. Am J Agric Econ 80:1214–1220

Troudet J, Grandcolas P, Blin A, Vignes-Lebbe R, Legendre F (2017) Taxonomic bias in biodiversity data and societal preferences. Sci Rep 7:1–14

Veríssimo D, Fraser I, Groombridge J, Bristol R, MacMillan DC (2009) Birds as tourism flagship species: a case study of tropical islands. Anim Conserv 12:549–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2009.00282.x

Veríssimo D, Vaughan G, Ridout M, Waterman C, MacMillan D, Smith RJ (2017) Increased conservation marketing effort has major fundraising benefits for even the least popular species. Biol Conserv 211:95–101

Wilson C, Tisdell C (2005) What role does knowledge of wildlife play in providing support for species’ conservation. J Soc Sci 1:47–51

Acknowledgements

Firstly appreciate all the support of the “Río Cruces” Research Center (www.cehum.org) and their staff; Patricia Möller, Daniela Contreras y Jorge A. Tomasevic. Also we want to thank the interviewers: Victor Bahamonde, Guisella Paredes y Marcelo Echeverria. The endless corrections by Carlos Molina and Thomas W. McGraw. The authors also appreciate the reviews by Catharina Druckerbrod and Regina Neudert for the review of earlier versions of the manuscript. Finally to Pablo Galaz for all the support during the fieldwork.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was partially supported by the DAAD (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst) and the River Cruces Research Center (Centro de Humedales del Río Cruces).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: VB, IARJ & MEM; data curation: MEM; formal analysis: VB & MEM; funding acquisition: IARJ & MEM; investigation: MEM; methodology: VB & MEM; project administration: MEM; resources: VB, IARJ & MEM; supervision: VB; validation: VB; visualization: MEM; writing—original draft: MEM; writing—review & editing: VB &MEM.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

All participants in the interview were told the objective of the study, the context, the use that the data collected would have, and that anonymity would be guaranteed.

Consent for publication

All authors give their consent for the publication of this article.

Additional information

Communicated by Stephen Garnett.

"This article belongs to the Topical Collection: Biodiversity appreciation and engagement".

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Espinosa-Molina, M., Rodriguez-Jorquera, I.A. & Beckmann, V. Effect and difference between the threatened and endemic status on the general public support towards wildlife species in a biodiversity hotspot. Biodivers Conserv 30, 3219–3241 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-021-02245-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-021-02245-0