Abstract

Agri-environment schemes (AES) have been established to counteract negative effects of agricultural intensification on e.g. semi-natural pastures and meadows. The efficiency of most AESs have, however, been poorly evaluated. We evaluated the success of a Swedish AES for the management of semi-natural pastures by comparing species richness and composition of vascular plants (except trees), epiphytic lichens and trees among pastures receiving higher (high value pastures) and lower levels of AES paymens (general value pastures). There was no difference in the number of tree species among high and general value pastures, even though AES regulations allow a maximum of 60 and 100 trees/ha in general and high value pastures, respectively. High value pastures had, however, a higher number of plant and epiphytic lichen species than common value pastures. Moreover, a higher number of pasture specialist plant species were indicative of high value pastures than of general value pastures. No lichen species indicating high value pastures are associated with habitats with low canopy cover (such as e.g. pastures). Finally, tree identity was an important factor for explaining the number and composition of epiphytic lichen species. Our study highlights that species groups can respond differently to agri-environment schemes and other conservation measures. Even though the effects are the desired on the diversity of one assessed taxon, this is not always the case for non-target organism groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anonymous (2012) Landsbygdsprogram för Sverige 2007–2013. http://www.regeringen.se/content/1/c6/08/27/24/0421beef.pdf. Accessed 30 Sept 2014

Berg Å, Ehnström B, Gustafsson L, Hallingbäck T, Jonsell M, Weslien J (1994) Threatened plant, animal, and fungus species in Swedish forests—distribution and habitat associations. Conserv Biol 8:718–731

Blom S (ed) (2010) Nya regler kring träd och buskar i betesmarker—hur påverkas miljön genom förändrade röjningar? Rapport 2010:8. Jordbruksverket

Bommarco R, Lindborg R, Marini L, Öckinger E (2014) Extinction debt for plants and flower-visiting insects in landscapes with contrasting land use history. Divers Dist 20:591–599

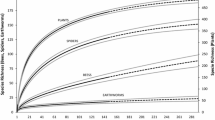

Colwell RK (2006) Estimate S: statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples. Version 8.2.0. Persistent URL <purl.oclc.org/estimates>

Colwell RK, Mao CX, Chang J (2004) Interpolating, extrapolating, and comparing incidence-based species accumulation curves. Ecology 85:2717–2727

Cousins SAO (2009) Landscape history and soil properties affect grassland decline and plant species richness in rural landscapes. Biol Conserv 142:2752–2758

Cousins SAO, Eriksson O (2001) Plant species occurrences in a rural hemiboreal landscape: effects of remnant habitats, site history, topography and soil. Ecography 24:461–469

Dengler J, Janisová M, Török P, Wellstein C (2014) Biodiversity of Palaearctic grasslands: a synthesis. Agricult Ecosyst Environ 182:1–14

Development Core Team R (2011) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. ISBN 3-900051-07-0

Dufrene M, Legendre P (1997) Species assemblages and indicator species: the need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol Monogr 67:345–366

Ekstam U, Forshed N (1992) Om hävden upphör: kärlväxter som indikatorarter i ängs- och hagmarker. Statens Naturvårdsverk, Solna

Ellis CJ (2012) Lichen epiphyte diversity: a species, community and trait-based review. Perspect Plant Ecol Evol Syst 14:131–152

Ellis CJ, Coppins BJ (2007) 19th century woodland structure controls stand-scale epiphyte diversity in present-day Scotland. Divers Dist 13:84–91

Geiger F, Bengtsson J, Berndse F, Weisser WW, Emmerson M et al (2010) Persistent negative effects of pesticides on biodiversity and biological control potential on European farmland. Basic Appl Ecol 11:97–105

Gelman A, Hill J (2007) Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Gilbert O (2000). Lichens. New Naturalist, Trafalgar Square

Gotelli NJ, Colwell RK (2001) Quantifying biodiversity: procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecol Lett 4:379–391

Hallingbäck T (1995) Ekologisk katalog över lavar. [The lichens of Sweden and their ecology]. ArtDatabanken SLU, Uppsala

Hanski I (1999) Metapopulation ecology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hawksworth DL, Rose F (1976) Lichens as pollution monitors. Studies in biology no 66. Edward Arnold Publishers, UK

Helm A, Hanski I, Pärtel M (2006) Slow response of plant species richness to habitat loss and fragmentation. Ecol Lett 9:72–77

Johansson V, Ranius T, Snäll T (2012) Epiphyte metapopulation dynamics are explained by species traits, connectivity, and patch dynamics. Ecology 93:235–241

Jonsell M, Weslien J, Ehnström B (1998) Substrate requirements of red-listed saproxylic invertebrates in Sweden. Biodivers Conserv 7:749–764

Jordbruksverket (2014) Vilken miljöersättning för betesmarker och slåtterängar kan jag söka? http://www.jordbruksverket.se/amnesomraden/stod/jordbrukarstod/miljoersattningar/betesmarkerochslatterangar/vilkenmiljoersattningkandusokafordinmark.4.51c5369e120aee363f080001848.html. Accessed 30 Sept 2014

Kleijn D, Sutherland WJ (2003) How effective are European agri-environment schemes in conserving and promoting biodiversity? J Appl Ecol 40:947–969

Kleijn D, Rundlöf M, Scheper J, Smith HG, Tscharntke T (2011) Does conservation on farmland contribute to halting the biodiversity decline? Trends Ecol Evol 26:474–481

Krauss J, Bommarco R, Guardiola M, Heikkinen RK, Helm A, Kuussaari M, Lindborg R, Öckinger E, Pärtel M, Pino J, Pöyry J, Raatikainen KM, Sang A, Stefanescu C, Teder T, Zobel M, Steffan-Dewenter I (2010) Habitat fragmentation causes immediate and time-delayed biodiversity loss at different trophic levels. Ecol Lett 13:597–605

Krok T, Almquist S (2001) Svensk flora, 28th edn. Liber utbildning, Stockholm

Lindborg R, Eriksson O (2004) Historical landscape connectivity affects present plant species diversity. Ecology 85:1840–1845

Lindenmayer DB, Margules CR, Botkin DB (2000) Indicators of biodiversity for ecologically sustainable forest management. Conserv Biol 14:941–950

Loreau M, Naeem S, Inchausti P, Bengtsson J, Grime JP, Hector A, Hooper DU, Huston MA, Raffaelli D, Schmid B, Tilman D, Wardle DA (2001) Ecology—Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: current knowledge and future challenges. Science 294:804–808

Nilsson SG (1997) Forests in the temperate-boreal transition: natural and man-made features. Ecol Bull 46:61–71

Öckinger E, Smith HG (2007) Semi-natural grasslands as population sources for pollinating insects in agricultural landscapes. J Appl Ecol 44:50–59

Öckinger E, Niklasson M, Nilsson SG (2005) Is local distribution of the epiphytic lichen Lobaria pulmonaria limited by dispersal capacity or habitat quality? Biodivers Conserv 14:759–773

Öckinger E, Hammarstedt O, Nilsson SG, Smith HG (2006) The relationship between local extinctions of grassland butterflies and increased soil nitrogen levels. Biol Conserv 128:564–573

Öckinger E, Lindborg R, Sjödin NE, Bommarco R (2012) Landscape matrix modifies richness of plants and insects in grassland fragments. Ecography 35:259–267

Plummer M (2003) Jags: a program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling. DSC Working Papers

Plummer M (2010) JAGS Version 2.0.0 user manual

Rundlöf M, Smith HG (2006) The effect of organic farming on butterfly diversity depends on landscape context. J Appl Ecol 43:1121–1127

Santesson R, Moberg R, Nordin A, Tönsberg T, Vitikainen O (2004) Lichen-forming and lichenicolous fungi of Fennoscandia. Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University, Uppsala

Thor G, Johansson P, Jönsson MT (2010) Lichen diversity and red-listed lichen species relationships with tree species and diameter in wooded meadows. Biodivers Conserv 19:2307–2328

Vessby K, Söderström B, Glimskär A, Svensson B (2002) Species-richness correlations of six different taxa in Swedish seminatural grasslands. Conserv Biol 16:430–439

Wilson JB, Peet RK, Dengler J, Pärtel M (2012) Plant species richness: the world records. J Veg Sci 23:796–802

Acknowledgments

Mattias Lif and Anders Eriksson assisted with the field work and Måns Svensson assisted with identification of lichens. Johan Ekroos gave valuable comments on a previous manuscript version. This study was funded by the Carl Trygger foundation. EÖ received additional support from the Swedish research council Formas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Daniel Sanchez Mata.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caruso, A., Öckinger, E., Winqvist, C. et al. Different patterns in species richness and community composition between trees, plants and epiphytic lichens in semi-natural pastures under agri-environment schemes. Biodivers Conserv 24, 1729–1742 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-015-0892-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-015-0892-x