Abstract

The prevention of aquatic invasive species is one of the most cost-effective management strategies for reducing negative ecological, economic, and social impacts to freshwater ecosystems. The release of leftover baitfish via the live bait trade has been identified as a high-risk pathway for introducing invasive species beyond physical barriers (e.g., mountains, dams). To assess differences in behavior surrounding live bait use and angler knowledge of invasive species, we conducted in-person angler surveys at waterbody access sites (i.e. boat ramps with available shore fishing and a shore fishing location with no boat ramp) along the Missouri River, above and below Gavins Point Dam (Yankton, South Dakota, USA). We were primarily interested in whether angler behavior and knowledge differed among fishing locations over the course of a year because of potential variation in risk. Gavins Point Dam is impervious to fish passage and prevents the spread of invasive silver carp Hypophthalmichthys molitrix and bighead carp H. nobilis (collectively known as bigheaded carp), but bigheaded carp could be transported above this dam by the use of live baitfish. Regardless of where respondents fished (above the dam/carp absent, below the dam/carp present, or both), 70% ± 11.12 of anglers used live baitfish and 57% ± 3.14 participated in ‘higher risk’ baitfish practices including release. Knowledge of bigheaded carp was limited, as only 2% ± 1.31 of respondents identified both bigheaded carp as invasive in an image collage, 51.82% ± 4.48 could not identify where invasive carp are present/absent, and 40% ± 3.34 of anglers had not received any information regarding bigheaded carp. These findings highlight limitations in angler knowledge, compliance, and identification of native and invasive species. Future implementable actions could include invasive species and baitfish release outreach via electronic media sources or additional signage that address these knowledge gaps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anthropogenic pathways, such as the aquarium and plant trade, can introduce species outside their current range (Hulme 2009). Recreational fishing is considered a high-risk anthropogenic pathway for the secondary spread of invasive species via the use and transport of live baitfish (McEachran et al. 2022). As juvenile invasive fish species appear similar to native baitfish species, they can be accidentally harvested commercially or recreationally and end up in angler bait buckets (Snyder et al. 2020). Once an angler has completed their fishing trip, they may decide to illegally release their baitfish into a waterbody instead of properly disposing of it, often unaware of the species they could be releasing (Kilian et al. 2012; Snyder et al. 2020). The release of live baitfish and water from bait buckets has been linked with introductions of invasive species (i.e., fish, pathogens, invertebrates) and subsequent declines in biodiversity (Kilian et al. 2012; Nathan et al. 2014). Therefore, managers might limit aquatic invasive species (AIS) introductions through preventative actions that target the activities of anglers that use live bait.

Managers can leverage information collected about angler behavior and knowledge, if it is available, to enact effective education and outreach programs aimed at overcoming knowledge gaps and increasing personal responsibility for compliance. Personal responsibility in fisheries can be defined as an angler’s feeling of obligation to sustain and enhance the environment and may cause an angler to be more likely to engage with management and comply with regulations (Larson et al. 2011). Outreach on invasive species, such as the “Stop Aquatic Hitchhikers! ™ (SAH!)” or the “Clean, Drain, Dry” campaigns, have been widely distributed across the United States to increase knowledge of AIS and promote feelings of personal responsibility towards preventing their spread (Seekamp et al. 2016). The presence of these campaigns and additional public education and outreach efforts has increased knowledge of invasive species, but additional approaches that target the activities of anglers are needed to successfully reduce risk (Seekamp et al. 2016).

In many river systems where they are invasive, silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) and bighead carp (H. nobilis; collectively known as bigheaded carp) are abundant but limited in their spread by physical barriers such as dams. Dams can be partial barriers or impervious to fish passage and have the ability to slow the spread of invasive species. The live bait pathway could spread bigheaded carp beyond current barriers because juvenile bigheaded carp can appear similar to many native species that are legal baitfish (Nathan et al. 2015). Bigheaded carp environmental DNA has also been found in water samples collected from bait retailers which could be a concern for the presence of invasive species within live bait (e.g., Nathan et al. 2015; Snyder et al. 2020; Mulligan et al. 2023). Additional spread of these species could impact habitat diversity, fishing and boating opportunities, and native fish species (Kolar et al. 2007; Kaemingk et al. 2007; Lu et al. 2020). Increased angler knowledge of AIS and baitfish best practices could help reduce the risk of invasive species introductions.

In this study, we assessed the risk of introductions via the live bait trade by surveying anglers on their baitfish use and invasive species knowledge upstream and downstream of a dam impervious to bigheaded carp spread without human assistance—Gavins Point Dam on the Missouri River (USA). Specifically, we surveyed 1) angler behavior (i.e., use, disposal, location) regarding live baitfish use and 2) angler knowledge of bigheaded carp identification and distribution. We were primarily interested in whether angler behavior and knowledge differed among fishing locations (above the dam/carp absent, below the dam/carp present, and fished at both locations) over the course of a year because of potential variation in risk. A combination of lacustrine conditions and anglers targeting specific species (i.e., walleye Sander vitreus) above the dam may contribute to increased baitfish use and pose a higher risk of invasive species spread via live baitfish release. We expected anglers to be familiar with bigheaded carp given their high profile as an invasive species (e.g., media coverage) and outreach focus by natural resource agencies in the Midwestern US (Mando and Stack 2019). Understanding angler behavior and knowledge will provide information on the role that anglers play in this invasive species pathway and identify opportunities for outreach and education.

Methods

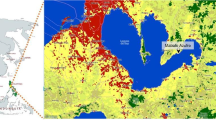

We conducted an in-person intercept survey to collect information on baitfish use and invasive species knowledge at waterbody access sites along the Missouri River below (bigheaded carp present) and above (bigheaded carp absent) Gavins Point Dam near Yankton, South Dakota, USA (Fig. 1). We surveyed anglers at and around boat ramps (n = 3) and a shore fishing location (n = 1; i.e., a public fishing dike). Anglers were able to fish from the shore at all locations, and the only location that anglers were not able to launch a boat was the public fishing dike. Surveys were only conducted at South Dakota access sites, but anglers licensed in either South Dakota or Nebraska both used these areas. We selected two locations to survey above the dam and two locations below the dam (Fig. 1). Surveys were conducted with two people on Friday, Saturday, or Sunday for approximately 9 h per day from September 22nd, 2023 to October 15th, 2023 (10 days total). Weekends were selected for sampling to maximize contact with anglers as they represent high use times with more interview opportunities (Dainys et al. 2022). September and October also represent high-fishing effort months within this system (Wickstrom and Schuckman 2006). One surveyor rotated between one of the three boat ramp locations for the duration of a sample day and approached anglers as they were arriving or leaving. The remaining surveyor drove between the remaining three sample locations (i.e., roving survey) and opportunistically approached anglers at boat ramps or while they were fishing from shore. At locations where anglers were not actively fishing or launching boats the roving surveyor would switch locations to maximize the number of anglers being surveyed. If an angler agreed to participate in the survey, they were shown our consent form and prompted to record their responses on a paper copy of the survey pamphlet. Anglers that did not consent to take the survey were thanked for their time and no further questioning was initiated due to our Institutional Review Board (IRB) requirements.

In-person angler survey locations for above the dam (bigheaded carp [Hypophthalmichthys sp.] absent; Gavin Point Boat Ramp, East Midway Boat Ramp) and below the dam (bigheaded carp present; Training Dike [shore fishing only], Riverside Boat Ramp) surrounding Gavins Point Dam in Yankton, South Dakota

The survey questions included three main areas of focus: angler behavior regarding baitfish, invasive species knowledge, and demographics (survey pamphlet containing questions and possible responses in Supplementary Fig. S1). Anglers were asked to report how many days they had fished, whether and where (above, below, both) they used live baitfish, and how they disposed of live baitfish above and/or below Gavins Point Dam in 2022. Responses for baitfish disposal were combined into smaller categories based on risk for analysis: ‘dispose of onshore’ and ‘dispose of in a designated area’ [lower risk] and ‘give to another angler’, ‘release into the waterbody’, ‘retain’, and ‘use in another waterbody’ [higher risk]. Dispose of onshore and dispose of in a designated area are recommended disposal methods to reduce the risk of AIS introduction or transfer. Although ‘give to another angler’ and ‘retain’ are legal baitfish practices in South Dakota, risk for AIS spread is increased in these scenarios. ‘Use in another waterbody’ and ‘release into the waterbody’ are considered the riskiest disposal methods and could result in AIS spread. Anglers that selected multiple disposal options were grouped with their higher risk response. For the invasive species knowledge section of the survey, anglers were asked to identify which species were invasive from an image collage (Supplementary Fig. S2) that included commonly used baitfish (creek chub Semotilus atromaculatus, common shiner Luxilus cornutus, and fathead minnow Pimephales promelas, gizzard shad Dorosoma cepedianum), other native species (river carpsucker Carpiodes carpio), and both species of juvenile invasive bigheaded carp (one image for each species). Pictures of the fish on the image collage were numbered, and respondents were asked to circle which numbers on the survey they thought were invasive. Additionally, anglers were asked to report, to the best of their knowledge, whether bigheaded carp are present above/below the dam and where they have received information regarding bigheaded carp. Anglers were considered accurate for bigheaded carp presence above and below the dam if they responded “no” and “yes”, respectively, for both questions. For the demographic section, anglers were asked to report what age category they fall into (i.e., 18 to 24, 25 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54, 55 to 64, and 65 or older) and the zip code of their primary residence.

For analyses, we first grouped anglers based on their responses to where they had fished in 2022 (above Gavins Point Dam [above], below Gavins Point Dam [below], both above and below Gavins Point Dam [both]) and tested for differences in other responses by fishing location using Fisher’s exact test followed by pairwise comparisons if statistically significant (Bonferroni corrected). If responses were not significantly different among locations, we averaged the percentages across the three locations and calculated standard error (± SE). Incomplete responses for specific questions were omitted from analysis and sample sizes are noted for each question within parentheses. Data analysis for the survey was carried out in program R (v. 4.2.2; R Core Team 2022), and comparisons were assessed for significance at α = 0.05.

Results and discussion

Out of the 198 licensed anglers that were asked to participate, we received 103 surveys from individuals who participated in recreational fishing above and/or below the dam in 2022 (55 [above] and 48 [below]. After grouping responses based on fishing location, we received surveys from 22 individuals (0 shore anglers, 22 boat anglers) that fished only above, 28 individuals (10 shore, 18 boat) that only fished below, and 53 individuals (13 shore, 40 boat) that fished above and below Gavins Point Dam in 2022.

Our survey results indicate that most anglers (70% ± 11.12; N = 98) use live baitfish and sometimes engage in risky or illegal behaviors when disposing of leftover live bait. Live baitfish use was higher for anglers that fished at both locations (N = 51; 84.3%) or only above the dam (N = 22; 77%), than anglers that fished only below (N = 25; 48%; different among locations, P = 0.006; Fig. 2). Walleye are intensively stocked in Missouri River reservoirs (Erickson et al. 2008) such as above Gavins Point Dam and are commonly targeted with live baitfish. High baitfish use above the dam may have been influenced due to lacustrine species presence. Of the respondents that used live baitfish, 57% ± 3.14 (N = 73) engaged in ‘higher risk’ practices and the proportion of these practices did not differ between locations (P = 0.681; Supplementary Fig. S3). 6.85% of anglers using live bait admitted to releasing live bait and other studies using in-person surveys have estimated slightly higher rates of baitfish release (18%, McEachran et al. 2022). However, online surveys result in much higher release rate estimates (20–60%; Kilian et al. 2012; Anderson et al. 2014; Snyder et al. 2020) indicating that social desirability bias for in-person surveys could be resulting in an underestimation of actual live bait release (McEachran et al. 2022). The combination of high baitfish use and ‘higher risk’ behaviors in an area where invasive bigheaded carp are not present and dispersal is impeded by a dam demonstrates the value of targeting invasion front locations with education and outreach to reduce the potential for anthropogenic invasive species spread.

a The percentage of anglers (N = 19) correctly identified both juvenile silver carp and bighead carp as invasive from the image collage of common baitfish, other native species, and bigheaded carps (not different among locations, P < 0.484; Supplementary Table S9). b The percentage of anglers (N = 99) that accurately or inaccurately identified the presence of bigheaded carp [Hypophthalmichthys sp.] above and below Gavins Point Dam

Nearly half of anglers had not received information regarding bigheaded carp and few anglers were able to identify these species, indicating an elevated risk of invasive species introductions via live baitfish release. The proportion of anglers who had not received information about bigheaded carp was not significantly different for anglers that fish above, below, or both above and below the dam (P = 0.725), with 40% ± 3.34 of anglers (N = 102) reporting to have not received information from word of mouth, electronic media sources, nor non-electronic media sources (Supplementary Fig. S4). Additionally, 19% of respondents that had heard about bigheaded carp had solely received information via word of mouth, which could have implications for the spread of potential misinformation (Seekamp et al. 2016). Therefore, public outreach events targeted towards all user groups and using a variety of communication methods could combat the spread of potential misinformation via word of mouth and decrease risky behavior (Eiswerth et al. 2011). Understanding the social networks of anglers may also be beneficial to combat misinformation. Only 2% ± 1.31 (N = 92) of anglers were able to solely (did not identify an incorrect species) identify both juvenile bigheaded carp as invasive (not different among locations, P = 0.484; Supplementary Fig. S5) and only 19% ± 3.17 were able to solely identify at least one species of bigheaded carp as invasive from the image collage. Interestingly, 44% ± 4.26 of anglers identified gizzard shad as an invasive species in the image collage. It is illegal in South Dakota to transport live gizzard shad away from waters in which they were harvested due to physical similarities with juvenile bigheaded carp (§ 41:09:04:04.). Harvesting gizzard shad below Gavins Point Dam and in certain waters of South Dakota is also illegal due to the presence of invasive species; however, live gizzard shad can be harvested and used as baitfish in Lake Lewis and Clark and the Missouri River above Gavins Point Dam (§ 41:09:04:03.). Prohibition of their transportation as a live baitfish in South Dakota could have contributed to respondents classifying them as invasive. Additionally, 48% ± 4.48 (N = 99) of anglers correctly identified that carp were present below the dam and not above the dam (not significantly different among locations, P = 0.571; Fig. 2). Results from our survey do indicate an improvement (+ 9%) in angler awareness of bigheaded carp presence below Gavins Point Dam from a previous survey (87% of anglers in our study; 78% in Bouska and Longhenry 2009). However, anglers are still commonly unable to identify invasive species (Drake and Mandrak 2014); therefore, a holistic approach may be needed to promote invasive species recognition to prevent AIS spread.

Although we expected to see variation in behavior and knowledge depending on fishing location (e.g., reservoir/above, river/below, or both), our results suggest that physical barriers may not create social barriers nor contribute to different levels of invasive species knowledge and risk. Instead, other demographic factors appeared to be more influential regarding AIS risk. For instance, age did not significantly differ between locations and ranged from 5.9% of anglers in the 18 to 24 age group to 21% of anglers in the 65 or older age group (P = 0.116; Supplementary Fig. S6). The age and state of residence of our surveyed angler population was similar to previous annual surveys in South Dakota (Gigliotti 2004; Bouska and Longhenry 2009). Differences in demographic characteristics, such as age, can contribute to differences in invasive species risk (McEachran et al. 2022) and prevention may require the use of a variety of outreach methodologies to reach different age groups. Younger ages may respond to educational outreach from electronic media sources, whereas older age groups may respond more to non-electronic media sources (McEachran et al. 2022). Although not the focus of this study, we found an interesting relationship between age and the source of information received regarding bigheaded carp. Word of mouth was prevalent in all age groups; however, anglers below the age of 54 received information predominantly from electronic media sources, whereas anglers above the age of 54 predominantly had not received any information regarding bigheaded carp (Supplementary Fig. S7). Future research should investigate this heterogeneity across age groups and the corresponding efficacy of educational campaigns. Additionally, travel distance may also be a factor that contributes to differences in behavior and knowledge among anglers. Surveyed anglers were from six different states which consisted of South Dakota (58% of respondents), Nebraska (32%), Iowa (6%), Minnesota (2%), Illinois (1%), and Michigan (1%) (N = 98). Approximately 41% of anglers surveyed were not South Dakota residents, which is similar to a previous study conducted from April–October in this area that found 47% of anglers fishing were not South Dakota residents (Bouska and Longhenry 2009). Of these individuals, 36.8% (n = 19; Supplementary Fig. S8) traveled more than 100 km; therefore, anglers may be unfamiliar with local fishing regulations. Additionally, educational programs related to AIS are typically state-specific, although multiple national campaigns exist (e.g., U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Clean, Drain Dry), which may result in anglers being unaware of regulations outside of the state in which they reside (Seekamp et al. 2016).

The combination of high baitfish use, risky behavior, and limited knowledge of bigheaded carp in this study highlights the need for AIS prevention strategies to incorporate regional education and regulations. Regional outreach could include a live baitfish guide that covers regulations from multiple states, identification of AIS of interest, and best baitfish disposal practices to increase AIS awareness and regulation compliance (Ludwig and Leitch 1996). Managers can use education programs to address the live bait pathway as boaters and anglers that use live baitfish are willing to learn about AIS and participate in prevention activities (Eiswerth et al. 2011). For example, implementing online AIS training or an invasive species examination at the time of purchasing a fishing license could increase angler knowledge and compliance. In turn, if boaters and anglers perceive that AIS is an environmental issue that negatively impacts them, they are more willing to act and promote positive social norms to reduce the risk of invasive species introduction and spread (Levers and Pradhananga 2021). Increased AIS information and personal responsibility could also reduce the spread of misinformation or misconceptions via word-of-mouth communication among anglers. Future research should investigate the effectiveness of educational campaigns among heterogeneous angler groups, the influence of the source of baitfish on AIS awareness (self-harvest vs purchase), and other factors influencing participation in biosecurity measures over a longer time period.

References

Anderson LG, White PCL, Stebbing PD, Stentiford GD, Dunn AM (2014) Biosecurity and vector behaviour: evaluating the potential threat posed by anglers and canoeists as pathways for the spread of invasive non-native species and pathogens. PLoS ONE 9(4):e92788. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092788

Bouska W, Longhenry C (2009) Annual fish population and angler use and sportfish harvest surveys on Lewis and Clark lake and the lower Missouri river, South Dakota, 2009. South Dakota department of game, fish and parks, wildlife division, annual report 10–07, Pierre.

Dainys J, Gorfine H, Mateos-González F, Skov C, Urbanavičius R, Audzijonyte A (2022) Angling counts: harnessing the power of technological advances for recreational fishing surveys. Fish Res 254:106410

Drake DAR, Mandrak NE (2014) Ecological risk of live bait fisheries: a new angle on selective fishing. Fisheries 39(5):201–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/03632415.2014.903835

Eiswerth ME, Yen ST, Van Kooten GC (2011) Factors determining awareness and knowledge of aquatic invasive species. Ecol Econ 70:1672–1679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.04.012

Erickson J, Rath M, Best D (2008) Operation of the Missouri River reservoir system and its effect on fisheries management. In: Allen MS, Sammons S, Maceina MJ (eds) Balancing FISHERIES management and water uses for impounded river systems. American fisheries society, Bethesda, Maryland, pp 117–134

Gigliotti LM (2004) Fishing in south Dakota, 2003 fishing activity, harvest, and angler opinion survey. HD-6-(2)-04.AMS. South Dakota department of game, fish and parks, Pierre.

Hulme PE (2009) Trade transport and trouble: managing invasive species pathways in an era of globalization. J Appl Ecol 46(1):10–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2008.01600.x

Kaemingk MA, Graeb BDS, Hoagstrom CW, Willis DW (2007) Patterns of fish diversity in a mainstem Missouri River reservoir and associated delta in South Dakota and Nebraska, USA. River Res Appl 23:786–791. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.1002

Kilian J, Klauda RJ, Widman S, Kashiwagi M, Bourquin R, Weglein S, Schuster J (2012) An assessment of a bait industry and angler behavior as a vector of invasive species. Biol Invasions 14(7):1469–1481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-012-0173-5

Kolar CS, Chapman DC, Courtenay WR, Housel CM, Williams JD, Jennings DP (2007) Bigheaded carps: a biological synopsis and risk assessment. American fisheries society, Bethesda, Maryland

Larson DL, Phillips-Mao L, Quiram G, Sharpe L, Stark R, Sugita S, Weiler A (2011) A framework for sustainable invasive species management: environmental, social, and economic objectives. J Environ Manage 92(1):14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.08.025

Levers LR, Pradhananga AK (2021) Recreationist willingness to pay for aquatic invasive species management. PLoS ONE 16(4):0246860. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246860

Lu G, Wang C, Zhao J, Liao X, Wang L, Luo M, Zhu L, Bernatzhez L, Li S (2020) Evolution and genetics of bighead and silver carps: native population conservation versus invasive species control. Evol Appl 13(6):1351–1362. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12982

Ludwig HR, Leitch JA (1996) Interbasin transfer of aquatic biota via anglers’ bait buckets. Fisheries 21(7):14–18. https://doi.org/10.1577/15488446(1996)021%3c0014:ITOABV%3e2.0.CO;2

Mando J, Stack G (2019) Convincing the public to kill: Asian carp and the proximization of invasive species threat. Environ Commun 13(6):820–833

McEachran MC, Mohr AH, Lindsay T, Fulton DC, Phelps NBD (2022) Patterns of live baitfish use and release among recreational anglers in a regulated landscape. N Am J Fish Manag 43:295–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/nafm.10747

Mulligan H, Schiller BJ, Davis T, Coulter AA (2023) Opportunities for regional collaboration and prevention: assessing the risk of the live bait trade pathway of invasive species. Biol 287:110342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.110342

Nathan LR, Jerde CL, McVeigh M, Mahon AR (2014) An assessment of angler education and bait trade regulations to prevent invasive species introductions in the Laurentian great Lakes. Manag Biol Invasions 5(4):319–326. https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2014.5.4.02

Nathan LR, Jerde CL, Budny ML, Mahon AR (2015) The use of environmental DNA in invasive species surveillance of the great lakes commercial bait trade. Conserv Biol 29(2):430–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12381

R Core Team (2022) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 1 November 2023

Seekamp E, McCreary A, Mayer J, Zack S, Charlebois P, Pasternak L (2016) Exploring the efficacy of an aquatic invasive species prevention campaign among water recreationists. Biol Invasions 18(6):1745–1758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-016-1117-2

Snyder MR, Stepien CA, Marshall NT, Scheppler HB, Black CL, Czajkowski KP (2020) Detecting aquatic invasive species in bait and pond stores with targeted environmental (e)DNA high-throughput sequencing metabarcode assays: angler, retailer, and manager implications. Biol Conserv 245:108430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108430

Wickstrom G, Schuckman J (2006) 2005 Angler use and harvest survey of the Missouri river in South Dakota and nebraska from fort randall dam to gavins point dam. South Dakota department of game, fish and parks, wildlife division, Annual report 06–16, Pierre.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station. H. Mulligan was funded by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks (SDGFP), South Dakota State University Graduate School and Department of Natural Resource Management, and the South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station. We gratefully thank the survey respondents who took the time to participate and Shane B. Bertsch (SDGFP), Justin Scholl (USACE), and Todd R. Larson (Yankton Parks, Recreation City Events) for site permission. We also thank Riley Mounsdon and Riley Wollschlager for taking the time to look over and provide feedback on the survey. We would also like to thank Benjamin J. Schall for providing a friendly review of the manuscript and reviewers at Biological Invasions for their comments on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AG, HM, AC conceived the project. AG, HM, MK, and AC planned the project and developed the survey. AG and HM collected and analyzed data. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. This research involved human subjects. Procedures carried out in this manuscript were approved by the South Dakota State University Institutional Review Board (IRB-2209006-EXM).

Data availability

Datasets used in this work are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gerber, A.L., Mulligan, H., Kaemingk, M.A. et al. Angler knowledge of live bait regulations and invasive species: insights for invasive species prevention. Biol Invasions (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-024-03378-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-024-03378-3