Abstract

This paper aims to discuss a well-known concept from argumentation theory, namely the principle of charity. It will show that this principle, especially in its contemporary version as formulated by Donald Davidson, meets with some serious problems. Since we need the principle of charity in any kind of critical discussion, we propose the way of modifying it according to the presupponendum—the rule written in the sixteenth century by Ignatius Loyola. While also corresponding with pragma-dialectical rules, it also provides additional content. This will be termed the dialectical principle of charity, and it offers a few steps to be performed during an argument in order to make sure that the participants understand each other well and are not deceived by any cognitive bias. The meaning of these results could be of great significance for argumentation theory, pragma-dialectics and the practice of public discourse as it enhances the principle of charity and makes it easier to apply in argumentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This goal of this paper is to carefully analyse the concept of the principle of charity (PC), and to show that it requires improvement in order to be applicable in a critical discussion. We will show that this can be done by utilising a rule formulated almost 5 centuries ago by Ignatius Loyola. This improvement employs a dialectical way of thinking about a discussion, thus we call it the Dialectical Principle of Charity (DPC). The concept is closely connected to the paradigm of pragma-dialectics, but—as will be shown—it is not limited to it. Therefore, this paper should be understood as seeking to improve PC, but also as a development of pragma-dialectics, and linking the concept of PC to pragma-dialectics.

2 The Principle of Charity—What Is It and Why Do We Need It?

The principle of charity (hereinafter PC) is a notion which is broadly used in the contemporary literature concerning interpretation and argumentation. However, there is no consensus on what exactly PC consists of. To the best of our knowledge, the first known mention of the principle of charity can be found in Jewish writings from the early third century BC:

הלטבב וירבד איצומ םדא ןיא

A person does not say things for naught.Footnote 1

This suggests that if any person makes a statement, then it is reasonable to assume that there is a rational reason for the person to have said this. Therefore, it is rational to take into consideration that, despite the fact that it seems to be pure nonsense, there is some rationale which justifies it.

In short, PC is a philosophical or communicational rule that encourages—when interpreting someone’s statement—that one should always assume the best possible interpretation (Baillargeon 2007, 78). Thus, as a rule of thumb, PC is about assuming that the speaker’s intended interpretation was the most rational, when there are several ways in which the claim may be interpreted. Neil Bearden in his talk Principle of Charity identifies two components (IDEASxP&G 2015):

A. Realising that the given situation (proposition, argument) is ambiguous;

B. Finding the best possible interpretation, which make it reasonable.

PC, according to Bearden, is based on two assumptions: “Most people aren’t that stupid,” and “Most people aren’t rude.” PC could be applied in several contexts and with distinguishable aims respectively. Firstly, it can be used to determine the reference of the interlocutor’s words (and, consequently, the meaning of her utterances). Let us consider the following example taken from Neil Wilson’s article (1959, 527):

Suppose that somebody—let’s say “Charles”—makes just the following five statements on “Caesar.” Let us also suppose we are ignorant of Roman history.

A. Caesar conquered Gaul.

B. Caesar crossed the Rubicon.

C. Caesar was murdered on the Ides of March.

D. Caesar was addicted to the use of the ablative absolute.

E. Caesar was married to Boudicca.

We may now consider what is the reference of “Caesar” in Charles’ intent. If we have some knowledge of history or literature, we will be aware that if Charles means Julius Caesar, statements from A to D are true. If, however, he meant Prasutagus (Boudicca’s husband), then the last claim (E) is true. Put simply, PC demands that we act in the first way. When interpreting we choose the best possible version that makes the largest number of statements of the opponent true, in this case Julius Caesar.Footnote 2 As Douglas Walton expresses in the dialectical rules, “when interpreting an ambiguous term in a text of discourse, the interpretation that makes sense of the discourse should be preferred. A meaning that makes the text absurd or meaningless should be avoided” (2000, 267). At this level W.V.O. Quine and Donald Davidson focus on radical translation and radical interpretation respectively in their writings (as far as those philosophical theories are the starting point for our considerations in this paper, we will present them below in more detail).

Secondly, PC might be used in the discussion process as a rule aiding the interpretation of the interlocutor’s arguments. In this case it is assumed that each participant in the discussion understands her interlocutor’s point of view, recognizes that it differs in some respects from her own, and tries to persuade the other person to change her mind.Footnote 3

In such cases, PC demands that if there are two possible interpretations of a statement or argument made by the interlocutor and one of them makes it false or fallacious and the other sound and rational, we should adopt the latter. Thus, to apply the principle of charity, one should not attribute logical fallacies, irrationality or falsehoods to the argument of another when an alternative interpretation of the utterance is available (after having taken all relevant contextual features into account)—an interpretation that makes it rational and plausible. We may therefore formulate two components of PC applied to argumentation:

-

A.

When interpreting, choose the best possible interpretation and skip the minor mistakes of the opponent’s argument.

When the proposition or the argument is ambiguous, one should choose the best interpretation, that this, the most reasonable one. If the argument contains some irrelevant problems or obvious mistakes in the argument, it is better to ignore them (if they are not crucial to the main point that the opponent is trying to make).

-

B.

Assume the good will of the opponent’s intentions

To put it in more simple terms, if the interlocutor’s argument seems problematic, it is good to assume that it is unintentional on their part, as long as it is reasonable to do so. It means that, if possible, one should give people the benefit of the doubt, and attribute issues in their arguments to a misunderstanding on their part, rather than to a malicious intent to deceive.Footnote 4

The third component might not seem essential, but it proves to be very useful in any discussions which are truth-oriented and especially in academic debates. It might be overwhelming, misunderstood or even redundant in everyday life arguments, but some authors include it in the charitable interpretation.

-

C.

Consider using a logically structured approach to the opponent’s argument.

It is highly beneficial, but very rare, to attempt to re-express your opponent’s position so clearly, logically structured, and fairly so your opponent might say: “Thank you for putting my thoughts so clearly!”

The component (c) might seem controversial however—sometimes putting one’s argument in a logical form may seem uncharitable to the interlocutor—especially if the discussion is not a purely philosophical debate between scholars. Arguments which have a maximal commitment to truth would certainly benefit from this procedure (actually, this is a good practice of such debates), but in more common arguments this may seem uncharitable to the person, who is “being corrected,” for it suggests the superiority of one side.Footnote 5

We may then summarise PC in general that it consists of (A) assuming the best possible interpretation (when the claim or argument may be understood in various ways), (B) assuming the good intent of the interlocutor, and optional (C), putting the argument in the logical form (if one needed).

Some would develop the third component even further, following Daniel Dennett, and improve the claim or argument on one’s own in order to criticise the best version of it (this has been termed a “steel man argumentFootnote 6”). Thus it is not limited to structuring the argument in a solely logical form, but also it enhances the argument in a way that seems to make the conclusion more justified. This, however, goes far beyond the interpretation, but might be—and in certain contexts we believe it is—a standard of a good discussion.

Now we may ask, why do we need to be charitable in a discussion? Obviously, there are several reasons for it (Stevens 2021a, 69–73). We will mention just two here, with the first being a methodological one. There are strong reasons to believe that PC is a necessary presupposition of any act or process of interpretation. That methodological assumption—i.e. that the people we try to understand share a common rationality and generally adequate picture of the world with us—justifies further expectations that those people would accept the clarifications and improved versions of their arguments, justifies the above outlined pragmatic applications of PC.

Of course, another reason for applying PC in a discussion may be found in pragma-dialectics.Footnote 7 For example, the founders of pragma-dialectics, Frans H. van Eemeren and Rob Grootendorst, say the say in rule 3 (the original version of rules):

A party's attack on a standpoint must relate to the standpoint that has indeed been advanced by the other party. (van Eemeren and Grootendorst 1995, 136)

This is the one of the basic rules that prevents us from committing the straw man fallacy when discussing, that is, attacking “on a view that the speaker attributes to his adversary, but that does not correspond to the adversary’s actual position, but rather to a distorted (misrepresented) version of it” (Macagno and Walton 2017, xiii). The arguer may only critique the argument that was formulated (and directed) by the other party. Therefore, if we want to increase the chances for a productive discussion, we should adopt PC.

Let us now move on to the more specific formulation of PC by Quine and (especially) Davidson. The reason for this is that both of them argued that PC is not some optional practice, but a rule which makes the very understanding of another person possible. As a consequence, the application of PC as postulated by Quine and Davidson seems to constitute a crucial step before any conversation or discussion can take place. It is worth noting that Davidson, as a philosopher of language, only referred to the PC understood as an interpretative tool, not a “procedure for critical discussion”—although his findings will be very useful for formulating the “argumentative PC.”

3 Davidson’s Principle of Charity

Quine formulated his version of PC in the context of radical translation. He holds that “fair translation preserves logical laws” because “even the most audacious system builder is bound by the law of contradiction” (2013, 53). There is a fundamental maxim of translation that “assertions startlingly false on the face of them are likely to turn on hidden differences of language” (2013, 54). “The common sense behind the maxim is that one’s interlocutor’s silliness, beyond a certain point, is less likely than bad translation—or, in the domestic case, linguistic divergence” (2013, 54). The last phrase reveals that, according to Quine, we are in a similar position regardless of whether we are trying to understand people from a completely foreign tribe or our long-term neighbour who speaks the same language as we do. The reason is that in both cases there are some sounds (or signs) made by a person to be understood, which we perceive and which await interpretation as meaningful expressions. Therefore, there are no essential epistemic differences between these two situations.

Quine’s perspective was further developed by Donald Davidson in his theory of radical interpretation.Footnote 8 Davidson also recognises that all the empirical evidence we have when interpreting the speech of another person are his or her utterances and behaviour. What we may reasonably assume (here Davidson agrees with Quine) is that those utterances are expressions of the beliefs of the person we are interpreting, i.e. she holds true. However, Davidson argues, “if all we have to go on is the fact of honest utterance, we cannot infer the belief without knowing the meaning, and have no chance of inferring the meaning without the belief” (2001, 142). In consequence,

“if all we know is what sentences a speaker holds true, and we cannot assume that his language is our own, then we cannot take even a first step towards interpretation without knowing or assuming a great deal about the speaker’s beliefs. Since knowledge of beliefs comes only with the ability to interpret words, the only possibility at the start is to assume general agreement on beliefs. (2001, 196)”

According to Davidson, therefore,

If we cannot find a way to interpret the utterances and other behaviour of a creature as revealing a set of beliefs largely consistent and true by our own standards, we have no reason to count that creature as rational, as having beliefs, or as saying anything. (2001, 136–37)Footnote 9

PC is then a methodological rule which constitutes a necessary condition for efficient and successful communication: “Charity is forced on us; whether we like it or not, if we want to understand others, we must count them right in most matters” (2001, 197).

Davidson also agrees with Quine that in this respect there is no difference between the interpretation of a foreign language and a mother tongue. The reason for that is that before one interprets the other person’s utterance, one cannot know that the interpreted person speaks the same language as the interpreter, i.e. one has to apply PC in order to find out that the other person is speaking the same language as one’s own. In consequence, “all understanding of the speech of another involves radical interpretation (see Davidson 2001, 125).Footnote 10

PC, when applied, leads to such an interpretation of the other person’s language utterances that “optimizes agreement” (Davidson 2001, 136). What is important, however, is the fact that this is agreement from our point of view, i.e. an agreement “optimised” by our interpretation of another’s utterances, an interpretation led by our standards of what is reasonable and true.

4 Problems with the Principle of Charity

The above-mentioned reason for Quine’s and Davidson’s versions of PC have been criticised by some philosophers as too strong. Critics hold that this version of PC not allows for an interpreter to recognize that the interpreted person might have made cognitive mistakes and could hold false beliefs. If we followed Quine and Davidson—it is claimed—it would be impossible for any disagreement of opinions between an interpreter and the person’s being interpreted to appear.

The problem may be formulated in a more detailed way when one takes into account a more refined formulation of the PC that one can find in the paper by Paul Thagard and Richard E. Nisbett (1983). They remark that the most general PC can be stated as follows: “Avoid interpreting people as violating normative standard” (1983, 251), and acknowledge that it should be differently stated with respect to the different domains in which PC could be applied, namely: translation, inferential behaviour, and choice behaviour. They propose the following three formulas for PC:

“Translation: Avoid translating subjects' utterances in such a way as to accuse them of holding contradictory or absurd beliefs.

Inference: Avoid interpreting subjects' inferences in such a way as to accuse them of violating normative rules of deductive or inductive reasoning.

Choice: Avoid interpreting subjects' economic behavior or other choices as violating normative standards of decision making. (Thagard, Nisbett 1983, 251)”

What is even more important for Thagard and Nisbett is that PC can be understood in a weaker or stronger sense. They detect several “force levels” of PC:

(1) Do not assume a priori that people are irrational.

(2) Do not give any special prior favour to the interpretation that people are irrational.

(3) Do not judge people to be irrational unless you have an empirically justified account of what they are doing when they violate normative standards.

(4) Interpret people as irrational only given overwhelming evidence.

(5) Never interpret people as irrational. (1983, 252)

Thagard and Nisbett then show that only levels (1)–(3) could reasonably be applied. However, according to them, there are no reasons to accept either (4) nor (5). Thagard and Nisbett argue that Quine’s rule that fair translation always preserves the laws of logic amounts to the strongest sense of PC, namely (5). They endorse, however, some examples which show that people sometimes deliberately violate the laws of logic—see for example paradoxical claims in religious discourse. In such cases a reasonable theory is available to us as to why those people are doing this. There are also sociological findings that people make a statistically significant number of logical fallacies (e.g. affirming the consequent or concluding post hoc ergo propter hoc) and psychological theories explaining why such mistakes are so widespread in society.

Thagard and Nisbett rightly remark that too strong understanding of PC, that is (4) or (5), is at odds with striving to educate society and improve our normative standards of rationality.

According to Trudy Govier (2018, 213), Thagard and Nisbett’s arguments also apply to Davidson’s understanding of PC, i.e. that Davidson account demands we accept (4) and even (5).

The critical remarks outlined above may be correct as regards Quine’s formulation of PC, but they miss the point with respect to Davidson’s view. First of all, Davidson explicitly states that we should take interpreted statements as true not always but only “in most cases,” that is “when plausibly possible,” and that according to his understanding of PC we “make maximum sense of the words and thoughts of others when we interpret in a way that optimizes agreement (this includes room, as we said, for explicable error, like differences of opinion)” (2001, 197).

As Jonathan Adler has remarked, Davidson’s choice of optimizing agreement over maximizing it is of crucial importance here (1996, 337). Optimized agreement could include the recognition of as many mistakes on the part of the person interpreted as it is reasonable, given all the empirical evidence concerning her cognitive situation, speech, and behaviour. This is what Davidson explicitly holds:

“the aim is not the absurd one of making disagreement and error disappear. The point is rather that widespread agreement is the only possible background against which disputes and mistakes can be interpreted. Making sense of the utterances and behaviour of others, even their most aberrant behaviour, requires us to find a great deal of reason and truth in them. To see too much unreason on the part of others is simply to undermine our ability to understand what it is they are so unreasonable about. If the vast amount of agreement on plain matters that is assumed in communication escapes notice, it’s because the shared truths are too many and too dull to bear mentioning. What we want to talk about is what's new, surprising, or disputed. (2001, 153; see also 200)”

In other words, Davidson’s version of PC assumes that any disagreement is only possible against a background of broader agreement, and any recognition of a mistake from the part of our interlocutor is only possible in the case she is right (by our standards) in many more matters. Without such a background of shared beliefs we would be unable to understand what we and our interlocutor disagree about. This background, however, may escape our notice, because it is too obvious to be spoken out. The inconspicuousness of what is salient for communication may seem paradoxical, but—as Adler remarks—it is in accordance with Gricean rules of conversation (1996, 335). Adler concludes: “Thus massive agreement in beliefs is compatible with extensive disagreement in what is said” (335)—for what is agreed about remains—for good reasons—unsaid.

Given the above remarks it seems implausible to believe that Davidson’s version of PC excludes disagreement between the interpreter and the interpreted person. Nevertheless, it still remains the case that these are the interpreter’s standards of rationality from the Davidsonian perspective and his or her views of what is true are used without question in the process of the interpretation and evaluation of any other statement. There is no room in the process of interpretation, as described by Davidson, for the acknowledgment of the possibility that it is the interpreter who has made a mistake and whose worldview is based at least partly on her cognitive biases, and—conversely—this is the person interpreted who is right in some cases of disagreement. Given the fact that human cognition is limited and not inerrant, we take this feature of PC to be a serious weakness. This weakness can also impair the other aspects of PC that we discuss below. Contrary, however, to the Govier’s worry that “the otherness of other minds and cultures may be lost if charity goes too far” (2018, 213), we suggest that the otherness of other minds and cultures is threatened if charity does not go far enough.

Our criticism of PC may be expressed briefly: (i) it assumes that the interpreter’s view is true,Footnote 11 and (ii) it reduces the possibility for a rational confrontation of beliefs. In consequence, the interpreter cannot really learn anything from the interlocutor, nor can the interlocutors know about their own potential mistakes.

We can also support the first (i) weakness of PC by referring to the bias blind spot (also called “better-than-average effect”), according to which the vast majority of people (over 75% in Pronin’s study)Footnote 12 rate their thinking skills as better than average. Being aware of this tendency, we should improve the principle of charity so it can help us avoid or mitigate this bias. What is more, the procedure of interpreting requires also the possibility of detecting one’s own mistakes, deceptions, or fallacies.

Regarding the second weakness (ii)—imagine person A and person B, where A makes a proposition P that seems absurd to B, but B—after employing PC—interprets P in a way that makes P true (acceptable). As a result, neither B confronts own’s view (and potentially find out that is wrong about P), nor A’s view is being confronted—so A cannot find out that is wrong about P, but also B cannot know A’s reason for believing P (and therefore, B cannot even try to question this reason).

Based on this, we conclude that PC in its current shape limits the chances for both sides to learn something new on the discussed matter, and additionally it is exposed to the blind spot bias. It is now clear that we need a modified form of PC which steers clear of the mentioned difficulties, but at the same time serve as a help for understanding one another, preventing us from fallacies such as the straw man, and contribute to critical discussion. This is why it would be epistemically beneficial if we could find a modification of PC which allows us to make such improvements. We suggest that in this endeavour one might draw on an old rule formulated by a sixteenth-century theologian, Ignatius of Loyola.

5 Presupponendum and the Dialectical Principle of Charity

Ignatius Loyola, a nobleman, soldier, and later a priest, at the beginning of his only book, Spiritual Exercises, proposed a ground rule, termed the presupponendum.Footnote 13 It reads:

“Every good Christian ought to be more eager to put a good interpretation on a neighbour's statement than to condemn it. Further, if one cannot interpret it favourably, one should ask how the other means it. If that meaning is wrong, one should correct the person with charity; and if this is not enough, one should search out every appropriate means through which, by understanding the statement in a good way, it may be saved. (1992, 7)”

Obviously, Ignatius wrote it for Christians, and only in a specific context. However, we will try to show that this may serve as an inspiration for creating a procedure which preserves all the insights leading to PC while allowing us to learn from encounters with different epistemic perspectives and substantially improving one’s own worldview.

Within Ignatius’ rule we may distinguish four steps, which in fact amount to a procedure of “presupposing,” which will be very useful for modelling a dialectical principle of charity (DPC):

-

1.

RETRIEVE (“to be more eager to put a good interpretation on a neighbour's statement than to condemn it.”)

If one cannot interpret it favourably, then:

-

2.

ASK (“One should ask how the other means it.”)

If that meaning is wrong, then:

-

3.

CORRECT (“One should correct the person with charity.”)

If this is not enough, then

-

4.

FIND OTHER WAY (“Search out every appropriate means through which, by understanding the statement in a good way, it may be saved.”)

Let us now analyse each of these steps carefully.

5.1 AD 1. Retrieve

The first step includes the PC discussed above (A–B): to put a good interpretation on the statement, and on the other’s intent. However, Ignatius says something more here: “be more eager to put …”—we may explain this, according to an idea of the social psychologist Thomas Gilovich:

For desired conclusions, we ask ourselves, “Can I believe this?”, but for unpalatable conclusions, we ask, “Must I believe this?” (1991, 84)

This means that human nature, according to psychologists, has the tendency to adjust the reason to pre-rational intuition. Jonathan Haidt explains this idea further:

when we want to believe something, we ask ourselves, “Can I believe it?” Then (as Kuhn and Perkins found), we search for supporting evidence, and if we find even a single piece of pseudo-evidence, we can stop thinking. We now have permission to believe. We have a justification, in case anyone asks. In contrast, when we don’t want to believe something, we ask ourselves, “Must I believe it?” Then we search for contrary evidence, and if we find a single reason to doubt the claim, we can dismiss it.” (2012, 98)

Ignatius, having a deep understanding of the human psyche (even though he lived in the sixteenth century!), asks us to change the direction of our own thinking (or rather pre-thinking) and to ask yourself “Can I believe in this—embodying a charitable interpretation?” Thus, instead of searching for any issues and mistakes in what the opponent has said, one should take the attitude of searching for any good ideas in it. Therefore, Ignatius emphasises in this first step that putting a good interpretation requires the virtue of constant searching for the good in everything.Footnote 14 It is not something more than the principle of charity, but it is rather the instruction of how to implement principle of charity. It is not only about “Did I understand it correctly?”, but also “Do I want to understand it correctly?” We think that this is a better question, for it acknowledges the tendency to accept what is already accepted. Thus such a question is a better safeguard from the confirmation bias described by the contemporary psychologists. The first step includes then asking this question and applying PC—which already shows that presupponendum is something more than PC.

Sometimes in public discourse we skip this step—when we hear something that seems to be “a nonsensical or dangerous absurd” we attribute the property of being afraid to face the truth, of being ignorant or simply bad to our opponent. Only when the answer is positive—that is, one wants to apply PC to what he or she hears—then one may proceed with the further steps.

5.2 AD 2. Ask

Most of the debates on PC do not take into account the fact that interpretation need not be a one way and a one-step act, but that in most cases it can be rather a two-way and multistep process. That is why we propose extending the principle into a procedure of acting between two sides in order to discuss the given matter in a critical and honest way.Footnote 15

During this process we formulate the initial interpretation of the statements of the interpreted person applying the PC. Keeping the issues mentioned in the above section in mind, we can question this initial interpretation, treating it as only hypothetical and then ask our interlocutor if our hypothesis was correct.

There is, of course, the broad issue of understanding the questions and answers. In such a process PC, especially at its methodological level endorsed by Davidson, has to be applied. The very possibility of recognizing a question as a question presupposes some commonality and agreement between the person who asks and the person who answers. The logic of questions and answers in the context of PC remains to be resolved. But what is important here is the clear acknowledgment that the process of interpretation should include questions as an integral part.Footnote 16

5.3 AD 3. Correct

The third step of the process inspired by Ignatius’ presupponendum fits perfectly with the aspect of PC which concern argumentation, like all the efforts one takes in order to reformulate our opponent’s arguments in a logically structured manner (component C of PC) or even creating a steel man argument according to Dennett’s idea. However, the interlocutor might not be willing to modify or improve his or her (controversial) argument or proposition. That is why one should present some critical comments, not for the purpose of engaging in a discussion, but only for the purpose of obtaining a charitable understanding of what it is that the interlocutor means to express in the argument. It does not entail entering the discussion and evaluating the issue itself, but rather simply presenting some initial critique, which would need to be addressed if one decides to persist in believing the controversial claim or argument. Therefore, it is also about outlining the possible weaknesses of a given stance or argument, just to make sure that one really understands it. After this step, one might be more willing to revise his or her argument. We call it an “initial critique,” since the line between critical questions and critique or counter-argument seems to be blurred—consider, for example, a discussion between, person A and person B, where A says p, which seems highly controversial to B. It is hard to determine when B asks “but if p, as you said, then it would imply q, wouldn’t it?”, and if q is obviously unacceptable then it is obviously an argument against p. Obviously, as a speech act this is “disagreeing”—but such an assertive question could also be considered as making sure that A persists in claiming that p (despite of difficulties involved) or whether A would want to reject p before moving on to the further discussion. Additionally, this step may result in knowing the reasons that A has for believing p. Therefore, this step is precisely this: presenting an initial critique, getting to know the interlocutor’s arguments, and possibly, improving his or her proposition or argument.

However, it should not be overlooked that according to the presupponendum we should correct errors “with charity” (also translated as “with kindness”). This is of great significance for the discussion, since it may help us to avoid fighting instead of cooperating—and this what argument really is—a form of cognitive cooperation rather than a conflict.Footnote 17 That is why formulating this step in such way seems to be crucial for any critical discussion. Given the fact that any actual process of interpretation and argumentation is not a purely logical endeavour (many non-cognitive biases may affect it) such an attitude of cognitive cooperation may constitute an important factor facilitating or even ensuring that we learn from those we are interpreting and improve our own worldview and criteria of rationality.

It’s also common today that people want to avoid arguments (understood as a reasonable and cultured debate rather than everyday arguments), and when they encounter differences in their views, they resign from further discussion. Even if what the interlocutor said was “absolutely ridiculous and fallacious or simply false,” people tend to avoid arguing with the other in order to avoid offending him or her. In fact, it may result in judging him or her as having a poor understanding of the subject. Only entering the argument may result in confirming whether one’s own view is better and more well-grounded than our opponent’s. Therefore, the presupponendum also preserves us from this, encouraging us to present a critique or one’s own argument and confront it with the other, so at least one side of the argument can benefit.Footnote 18

5.4 AD 4. Find Another Way

The last step is the most important one. In the original formulation of Ignatius it reads: “Search out every appropriate means through which one’s statement can be improved and one could be right.” Here we propose understanding this step as an acknowledgment that in cases in which we recognize the differences between our worldview and the interpreted views of the world it is not our worldview but the other one that may be right.

Such cases demand that we modify PC in its methodological aspect developed by Davidson. As a reminder, his method “is intended to solve the problem of the interdependence of belief and meaning by holding belief constant as far as possible while solving for meaning” (2001, 136), and “this is accomplished by assigning truth conditions to alien sentences that make native speakers right when plausibly possible, according, of course, to our own view of what is right” (2001, 136).

The problem, however, is that presupponendum’s fourth step suggests that one should question one’s own view of what is right.Footnote 19 Having adopted such an attitude, it demands that we change PC into DPC, or we question one’s own view of the discussed matter. Stevens formulates a similar proposal (2021a, 73). She does not explain, however, how one can fulfil Davidson’s PC postulate. Stevens only remarks vaguely that “completely taking the perspective of another is impossible; it would require the interpreter to become the other” and “that every interpretation carries some of the interpreter with it” (2021a, 74). However, if we adopt a dialectical understanding for the principle of charity, such a weakness is no longer related to interpretation. This is because DPC requires a few interactions between the interpreter and interpreted, such as feedback question, rephrase, improving one’s argument and some initial critique—all of these are employed in order to agree on what one wanted to say. Therefore, we are no longer “closed in the infinite mental process” of figuring out what one wanted to say. The DPC procedure provides both sides with a clarification (and optionally, an improvement) of what was said.

The problem of the interdependence of belief and meaning must now be solved in a more complicated way than Davidson himself suggests: namely by holding meaning constant as far as possible, while solving for belief (and holding a belief constant only when necessary).

Such a modification does not amount to a denial that “disagreement and agreement alike are intelligible only against a background of massive agreement,” or that “applied to language, this principle reads: the more sentences we conspire to accept or reject (whether or not through a medium of interpretation), the better we understand the rest, whether or not we agree about them” (Davidson 2001, 136). It does, however, amount to adopting the procedure which can be characterised as follows: start with the application of PC as Davidson describes it; having reached, however, some amount of agreement,Footnote 20 seek any signs of disagreement: try to find the statements you are able to interpret as an expression of opinions different than yours (holding meaning constant, while solving for belief). Having identified such statements, try to shift your epistemic perspective, i.e. try to imagine how the world would look like if any of that statements were true (and your previous belief on the issue in question were false), try to find any possible reason for its truth, try to act as if it were true, etc.—i.e. make every possible effort to save that statement (assuming we initially agree as regards its meaning while disagreeing with respect to its truth value); on the basis of the previous steps, adjust the rest of your initial beliefs accordingly.

This 4-step procedure of DPC can be summarised as follows:

When you encounter a situation where the interlocuter believes in a proposition or argument which seems unjustified or even false:

-

(1)

(1) Presuppose the best interpretation of the proposition or the argument;

if it still seems absurd, then

-

(2)

(2) Ask the interlocutor how he or she understands the proposition or the argument;

if it still seems absurd, then

-

(3)

Formulate initial critique of the proposition or the argument and analyse the interlocutor’s reasons for it. Eventually, modify or improve the proposition.

if it still seems absurd, then

-

(4)

Question your own view which contradicts the discussed proposition.

It is worth to note that after questioning one’s own view (step 4) the DPC procedure may be repeated—in principle, the process of interpreting and improving could never stop, however, looking at how people actually discuss, at some point the interpretation and improvements stop.

In order to prove this model for critical discussion, let us consider various scenarios in which DPC can be applied in a discussion. Let us start with person A claiming that P. To person B P seems absurd, but B presupposes that A is rational and searches for such an interpretation of P which could make it true (step 1). After this fail, then B moves to the second step—B asks A whether he or she really means P (this is a pure question—aimed at obtaining an answer).Footnote 21 B can also rephrase P (“so you are saying that …”) in order to make sure that he or she really has a good understanding of what A said. Now, A has two choices: either A changes his claim to P’ or A stands pat and claims that P. In the first scenario B may consider whether P’ is acceptable, and if there is a reason S for not accepting P’, whether it is possible to reject S (step 4). In the second scenario, when A sticks to P, B may express the initial critique of P (step 3)—it might refer to P itself (“isn’t that a case that not-P?”) or it might refer to the negative consequences of P (“if P, then Q, and Q is not acceptable, right?”).

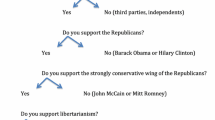

Such an initial critique may also lead B to slightly improve P (creating a steel man argument), that is to propose P’ instead of P. Obviously A may refuse or reject such an improvement—then A would have to propose some reason R justifying P. In this case B will consider such a reason and try to question his or her own view in order to accept it (step 4). If, however, A would accept the improvement, then B would have to consider accepting P’ or, if there is a reason S for not accepting P’, whether it is possible to reject S (step 4). All the DPC steps and scenarios in a discussion are presented in Fig. 1.

Let us consider the following example to show how the discussants would benefit if they adopt DPC. We will refer to a discussion that took place on Channel 4 News between the Canadian psychologist, Jordan Peterson, and the British journalist, Cathy Newman.Footnote 22 The discussion is mainly focused on the male and female roles in the postmodern world, and the following extract is mainly dedicated to the gender pay gap. Peterson tries to explain that the gender pay gap, if it occurs, is caused by multiple reasons, not simply by gender—and one of them is a difference between female and masculine traits:

-

Peterson: [Female traits] don’t predict success in the workplace. The things that predict success in the workplace are intelligence and conscientiousness. Agreeableness negatively predicts success in the workplace. And so does high negative emotion.

-

Newman: So you are saying that women aren’t intelligent enough to run these top companies.

-

Peterson: No, I didn’t say that at all.

-

Newman: You said that female traits don’t predict success.

-

Peterson: But I didn’t say that intelligence wasn’t. I didn’t say that intelligence and conscientiousness weren’t female traits…

-

Newman: Well, you were saying that intelligence and conscientiousness by implication are not female traits.

-

Peterson: No, no. I’m not saying that at all!

-

Newman: Are women less intelligent than men?

-

Peterson: No, they’re not. No, that’s pretty clear. The average IQ for a woman and the average IQ for a man is identical. There is some debate about the flatness of the distribution. Which is something that James Damore pointed out, for example, in his memo. But there’s no difference at all in general cognitive ability. There’s no difference to speak of in conscientiousness. Women are a bit more orderly than men and men are a little bit more industrious than women. The difference isn’t big. (Channel 4 News 2013)

Peterson’s claim is that (C) one of the reasons that women statistically make less money than men is the difference between the personality traits. This is supported by the following premise: (P) women are more agreeable than men. However, he also mentions two other traits which might be understood as an implicature that intelligence and conscientiousness are not female traits, which might be seen as a different claim (C’).

Now Newman is trying to interpret what Peterson said, but (most likely because of these implicatures interpreted as a part of C) Newman rephrases his claim in such a distorted way (R): “So you’re saying that women are less intelligent than men?” This however, is a very good proof of whether she understood the claim well. Of course, it is not what Peterson said, and should be seen as a strawman fallacy, but in response Peterson reminds her (twice!) that this is not what he said. In his second response he makes it clear that he did not say that intelligence and conscientiousness are not female traits—and finally express his initial claim more precisely, so it no longer includes the implicature (C).

Therefore, we may see how the discussion benefits from a DPC procedure: the feedback question (step 2) helps Newman to understand Peterson well, and thanks to the initial critique (step 3) the starting claim is slightly modified. We may simplify the discussion as below:

-

P: C

-

N: R?

-

P: No, I didn’t say R.

-

N: Yes, but you said C’.

-

P: Yes, I said C, but I didn’t say R.

-

N: But C implies R, right?

-

P: No, I didn’t say that!

-

N: Is R the case?

-

P: No, obviously R is false.

Obviously, there is a lot to say how it could benefit more from employing DPC—firstly, by adopting the best possible interpretation in step 1, which would most probably reduce the occurrence of strawman questions, and lead to clarifying the implicatures.

In the actual discussion, neither Newman nor Peterson made the fourth step of DPC. It would be worth imagining how such a move might look like. Let’s take Newman’s perspective. Her initial assumption seemed to be that it is gender itself that is the cause of the gender pay gap. So, the fourth DPC step would be at least to allow that Peterson might be right when he claimed that these are some female traits which are one of the causes of the gender pay gap. Had she allowed that, she might actively seek out those female traits, which might enable her to carefully investigate similarities and differences between genders. On the other hand, had Peterson allowed that Newman was right in that it is gender itself that is the main reason for the gender pay gap, he might actively seek out gender stereotypes widespread in society and all of the unjust inequalities which are based on those stereotypes. It is impossible to predict the outcome of the discussion in a case both sides had made the fourth step of DPC, nevertheless it would looked like differently than in the actual case, being less confrontational and epistemically more productive.

6 Discussion

There might be various problems which seemed important to discuss after the presentation of DPC, namely: (1) what is the relation between PC and DPC, and what makes the latter better for a critical discussion? (2) PC is about interpreting what one said, and DPC extends this—should any kind of principle of charity include argumentation? (3) Many of the components of DPC may be found in pragma-dialectics—what is the difference between DPC and pragma-dialectical rules for critical discussion? We will examine each of these points below.

6.1 Why is the Dialectical Principle of Charity Better than the Principle of Charity for a Critical Discussion?

DPC is an enhanced version of PC, which constitutes a better procedure for a critical discussion and helps it to avoid several fallacies which impact PC.

Firstly, it not only tells us to adopt the best possible interpretation before we evaluate one’s argument (which is only the first step), but also to make sure we understood it correctly by means of clarifying questions (the second step). In this way it “opens us” to what one really thinks, where PC closes us in what we think that one thinks (based on what they said). Therefore, it is no longer a mental activity, but a procedure of a cognitive cooperation that we call a discussion.

Then, if we are sure that the argument is fallacious, it requires that we present our counterargument with kindness, and diligently analyse our own reasons (third step). In this way it forces us to understand one’s reasons for believing in the proposition, and invites us to critically examine them. Additionally, it also exposes our view to the critical evaluation, so we can not only find out why one believes in the proposition, but also why our reasons might be insufficient to refuse to accept the proposition.

Finally, we question our own reasons for rejecting the argument of another (fourth step). In this way it decreases the potential for fallacy and helps to build a substantive, efficient, and cultured discussion. We may even call it a “procedure,” for it refers to a two-way and multistep process engaging at least two agents who investigate the given issue together (steps 2 and 3). Based on the fact that it requires two sides to cooperate (asking, answering, arguing) in order to achieve a common goal (cognitive benefit) we have termed it the “dialectical” principle of charity (in this way it also corresponds to pragma-dialectical heritage). The fourth step makes it even more critical, for it requires that we question our own beliefs and the reasons supporting them.

Now we need to consider how DPC avoids the critique formulated against PC in Sect. 3. To weakness (i) we can answer that it does not assume that the interpreter is right, but rather we compel the interpreter to imagine that he or she is wrong in that matter (the fourth step). It counteracts the bias blind spot and requires that we question our own beliefs and their reasons. To weakness (ii) we would answer that it gives the interpreter the opportunity to better understand the interlocutor (the second step), and also that it compels a rational confrontation (not only increasing its possibility), in which both arguers can identify their own fallacies, unjustified beliefs or weak inferences (the third step). If the arguers hold conflicting views, they will certainly identify this difference, and have greater chances to determine the better idea in the discussed matter.

It is worth mentioning that the procedure described here is not something that has been created by a few philosophers from their armchairs. It is rather based on observations of how good critical discussions are conducted in order to increase the cognitive benefits for all participants. The Ignatian presupponendum is an example of best practice which has inspired the formulation of the four-step procedure employing principle of charity.

6.2 Should the Principle of Charity Include Argumentation?

As mentioned above, some authors (see Lewiński 2012, Stevens 2021a, b) claim that PC developed and used in the philosophy of language (as a principle governing interpretation, hereafter called “charitable interpretation”) and PC applied in argumentative theory (hereafter called “charitable argumentation”) are so different that they can be considered and discussed separately. The main differences between the two are presented as follows: (1) while a charitable interpretation is seen as necessary condition in the process of understanding, charitable argumentation can take place when understanding is secured; (2) while charitable interpretation assumes a basic consensus of beliefs between the interpreter and her interlocutor, charitable argumentation assumes that there is recognized differences of opinions between interlocutors. According to the perspective developed here, however, i.e. when PC is transformed into DPC, charitable interpretation and charitable argumentation should not be separated.

First of all, if Quine and Davidson are right that interpretative PC is obligatory for any kind of communication, then charitable interpretation is also applied in discussion—which blurs the line between the charitable interpretation and charitable argumentation. Therefore, charitable argumentation includes charitable interpretation as its internal part.

On the other hand, we have shown that the radical interpretation described by Davidson not only requires us to assume that both interlocutors share the majority of beliefs, but also that they are able to recognize some disagreements between them. For that reason, charitable interpretation does not preclude the exchange of arguments and attempts to persuade one’s interlocutor of to one’s own point of view.

Finally, PC as described by Davidson closely links interpretation, i.e. ascribing meanings to the interpreted utterances, with (charitably) ascribing beliefs to the subjects who use those utterances. For that reason, when interpretative PC is extended into DPC—a procedure which includes questions, answers and the exchange of arguments—one cannot expect a clear distinction between the process of interpretation and the process of discussion, since the former includes elements of the latter.

6.3 Is the Dialectical Principle of Charity Different than Pragma-Dialectical Rules for a Critical Discussion?

However, another issue needs to be addressed here—one may ask, what is the difference between pragma-dialectics (PD) and DPC? Aren’t they very similar descriptions of how a critical discussion should look like?Footnote 23 Obviously, the dialectical principle of charity corresponds closely to DP, which “constitutes a separate and different standard or norm for critical discussion” (van Eemeren and Grootendorst 1995, 136).Footnote 24

As mentioned above, the authors of PD partly describe DPC—the pragma-dialectical rules required to interpret the opponent’s claims “as carefully and accurately as possible.” We read in rule 10:

“[One] must interpret the other party's formulations as carefully and accurately as possible. (van Eemeren and Grootendorst 1995, 136)”

This clearly refers to the process of interpreting and rephrasing the opponent’s argument or claim—which is step 1 of DPC. In later formulation of pragma-dialectical rules, van Eemeren and Grootendorst advise to ask for clarification, if needed:

“To be on the safe side, discussants who doubt the clarity of their formulation do well to replace it by a formulation that they consider to be clearer, and discussants who doubt their interpretation do well, to be on the safe side, to put it to the other discussant and to ask for an amplification, specification or other usage declarative. (van Eemeren and Grootendorst 2003, 384)”

This obviously covers step 2 of DPC—asking how the interlocutor understands the claim, and ensures that before the discussants start to develop arguments and criticise, they share the same understanding of the claim or the argument. Finally, as already mentioned, rule 3 of PD only allows arguing over the standpoint that has been advanced (van Eemeren and Grootendorst 1995, 136). This refers to the step 3 of DPC—formulating an argument against the interlocutor's claim, and analyse the reasons supporting it.

However, it misses the most important aspect. Step 4 requires an additional self-reflection, and questioning one’s own view, which was not included in pragma-dialectical for critical discussion. We believe that this is of a great significance for improving the way we conduct discussions—the final step,Footnote 25 which enforces questioning one’s own view, helps to aim the disagreement at the cognitive purpose (this however needs a complete change of how the discussion is commonly perceived—it is more a war than a dance, to use Lakoff and Johnson’s metaphor).

There is also another reason for developing DPC—the notion of the principle of charity, commonly used in informal logic, argumentation theory and critical thinking, is known and referred to also outside the paradigm of pragma-dialectics. Therefore, the improved concept is independent of pragma-dialectics in the methodological sense—one does not need to know and follow all of the PD rules in order to adopt DPC. What is more, since DPC is similar to some degree PD, we believe that it links two different concepts: pragma-dialectical rules for critical discussion and the concept of principle of charity (developed initially in the philosophy of language and later in argumentation theory).

7 Conclusion

In this paper the concept of the principle of charity has been analysed in its contemporary formulations. Some of the relevant difficulties have been discussed, namely exposure to biases and reducing the possibilities for cognitive benefit. Since the principle of charity is needed for critical discussion, the following modification has been proposed: the dialectical principle of charity. DPC is based on Ignatius Loyola’s rule, presupponendum, and consists of four steps: (i) presupposing the best interpretation of what one said; if needed—(ii) asking whether it was understood it correctly; if needed—(iii) formulating some argument against it, analysing its reasons; if needed—(iv) questioning our own view which contradicts the discussed proposition. We believe that DPC can avoid the weaknesses of PC, and that it constitutes a good procedure for any critical discussion.

Notes

Attributed to Rabbi Meir (a Jewish sage), in Arakhin 5a (published in the early third century BC), also in Ketuvot 58b (see: Talmudology 2015).

Alternatively, PC could result in mixed disambiguation, such as all statements are true, but they refer to different objects—the name “Caesar” in propositions A–D refers to one, and “Caesar” in proposition E it refers to the other Caesar.

Some call it “Hanlon’s razor,” (“Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity”) (Bloch 1980, 52). This rule, named after and attributed to Robert J. Hanlon, suggests that one should not attribute malice to actions or words of the person when it can be explained by other causes such as misunderstanding the topic. Hanlon’s razor can be treated as a supplement to the PC, so it consists of not only assuming the intelligence but also the good will of the interlocutor. There is a problem here, however, for—as the above quote from Bloch suggests—sometimes good will (“never attribute to malice”) is assumed on the cost of intelligence (“that which is adequately explained by stupidity”).

We are grateful to Daniel Spencer from the University of St. Andrews for this remark. We may answer to this remark that this depends on the way in which one improves or clarifies the other’s claim, and the context in which the argument is rooted (in some discussions it is desirable, and in some is not). Nevertheless, one may always try to logically organise the opponent’s view without expressing this loudly and respond to the improved version of it, e.g., when person A says “Men always become less loving after 20 years of marriage,” then person B may address this claim with a tacit limitation of it (“Most men than person A knows gets less involved after 20 years of marriage”) and argue with the corrected person A’s claim without correcting A’s claim explicitly.

Dennett not only advises us to choose the best possible interpretation of the given statement, but to improve the statement on our own and to criticise the strongest version of the argument that you can build (2013, 39). By doing this, you are essentially creating a steel man argument, which is an improved version of your opponent’s argument. This is the opposite of a straw man argument, which involves distorting your opponent’s views in order to make it easier to attack. Dennett proposes fours steps of PC (he attributes it originally to A. Rapoport): (1) attempt to re-express your target’s position so clearly, vividly and fairly that your target says: “Thanks, I wish I’d thought of putting it that way;” (2) list any points of agreement (especially if they are not matters of general or widespread agreement); (3) mention anything you have learned from your target; (4) only then are you permitted to say so much as a word of rebuttal or criticism (2013, 39).

It needs to be noted here that the pragma-dialectical approach to a critical discussion does not refer to the notion of PC. As will be shown here, it covers a lot of its components, but they are included at various stages in the pragma-dialectical procedure for discussions. This is also the main reason for developing the concept of PC (instead of simply adopting pragma-dialectical rules for critical discussion)—one may derive a similar procedure for a critical discussion from a simple and already well-known concept such as the principle of charity.

The analysis of the difference between radical translation and radical interpretation lies beyond the scope of this paper. Here we can acknowledge that: (1) despite all the differences between their views, Quine and Davidson agree on the importance of the “charitable” attitude; (2) this is precisely the point which is relevant for the further investigations.

Accordingly, it is reasonable to apply two principles to the interpreted person (see Davidson 1991, 158):

The principle of coherence, which “prompts the interpreter to discover a degree of logical consistency in the thought of the speaker.”.

The principle of correspondence, which “prompts the interpreter to take the speaker to be responding to the same features of the world that he (the interpreter) would be responding to under similar circumstances.”.

Trudy Govier has objected that such an assimilation of the cases of interpretation a foreign tribe and that of understanding a close neighbour is too hasty (2018, 207–8). She acknowledges that one “can build up a spectrum of cases of varying degrees of difficulty in understanding, such that the foreign tribe is at one end of the spectrum and close individuals in our own ‘tribe’ are at the other,” but argues that “differences of degree can accumulate to make significant differences” (2018, 208) and concludes that such a significant difference emerges between the “foreign tribe” case and the “close neighbour” case. Govier’s argument seems unconvincing to us —she neither presents the supposed difference in a detailed way nor meets the arguments endorsed by Quine or Davidson.

This also leads to an interesting paradox in democratic societies, as Scott R. Stroud terms it a “democratic riddle”: on the one hand we want to be charitable and open to others and their different views, but on the other hand we argue for certain political and social ideas, which seem right to us. a puzzle of democracy: “The puzzle of democracy concerns how we balance openness and assertion with our tendencies to be hardened partisans even when we think we are being open. An orientation of deep charity toward the others involved in our social interactions and disputes is a vital part to solving such a puzzle concerning assertion of views and openness to the assertions of other partisans” (2017, 9).

This study was conducted on Stanford undergraduates, where 75–85% rated their themselves “better than others within their group”—which obviously cannot be true (Pronin, Lin, and Ross 2002; Pronin, Gilovich, and Ross 2004). The study was repeated with similar results, and developed (Pronin and Kugler 2007; Chandrashekar et al. 2021).

Carl Starkloff, a Jesuit, claimed it can be implemented in any form of discourse. He, for examples, advises how to apply Ignatius’ presupponendum to intercultural dialogue (1996, 11).

The very fact that Ignatius referred to “putting a good interpretation” shows that the idea of the principle of charity (yet not named in that way) was known far more before Davidson’s formulation or pragma-dialectical rules for discussing).

The same was also suggested in the later formulation of the pragma-dialectical rule (rule 2): “discussants who doubt their interpretation would do well, to be on the safe side, to put it to the other discussant and ask for an amplification, specification, or other usage declarative” (van Eemeren and Grootendorst 2004).

A recent study also recommends this is as a rescue from a strawman fallacy “a more cooperative structure is required, one that asks arguers to help each other in developing positions and arguments and that often requires charitable interpretation” (Stevens 2021b, 118).

According to Lakoff and Johnson’s famous metaphor “argument as a dance” (see: Lakoff and Johnson 1980).

Either the interpreted interlocutor will benefit by knowing their own mistake or the interpreter will benefit by knowing that his or her critique is weak or unjustified. Therefore, the confrontation increases the chances for a cognitive profit anyway, and including it as an element of the dialectical principle of charity can avoid the weaknesses of PC.

A similar idea of including such a self-critical question to the principle of charity was recently presented by Katharina Stevens: “Charity as I describe it asks more of the interpreter than identifying a version of the offered argument that she finds convincing as strong charity does. Rather, it requires the attempt to gain insight into the reasons her interlocutor is trying to offer from the interlocutor’s point of view … It asks the interpreter to imagine herself different than she really is. So it may require large amounts of intellectual and emotional energy, empathy, and open-mindedness, and it can be painful” (Stevens 2021b, 74; see also: Lewiński 2012).

This is where one finds the suggestion of how to resolve the problem endorsed by Stevens, that “every interpretation carries some of the interpreter with it” (2021a, 74). However, as we noted according to Davidson, there is a significant level of agreement between the discussants, which makes possible to detect a disagreement. This shared part of beliefs is the starting point of interpretation, and this is basically what “interpretation carries with it.”.

We refer here to the distinction to four types of questioning: pure questioning, assertive questioning, rhetorical questioning and challenge questioning. For more on questions in argumentative dialogue see: (Hautli-Janisz, et al. 2021).

The discussion became famous as an example of a strawman fallacy, committed several times by Newman, and manoeuvred very well by Peterson.

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for this remark.

By “critical discussion” we mean a procedure, in which “the protagonist and the antagonist try to find out systematically whether the protagonist’s standpoint is capable of withstanding the antagonist’s criticism” (Eemeren and Grootendorst 2003, 365).

Additionally, this final stage may lead to the belief change—and that would happen in the “argumentation stage,” not in “concluding stage,” as PD names it. Therefore, this constitutes another difference—in PD the processes of interpretation, argumentation, and belief change (or at least questioning one’s own view) are far more interwoven.

References

Adler, Jonathan E. 1996. Charity, Interpretation, Fallacy. Philosophy & Rhetoric 29 (4): 329–343.

Baillargeon, Normand. 2007. Intellectual Self-Defense. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Bloch, Artur. 1980. Murphy's law, book two : more reasons why things go wrong. Los Angeles: Price Stern Sloan.

Chandrashekar, Subramanya Prasad, Siu Kit Yeung, Ka Chai Yau, Chung Yee Cheung, Tanay Kulbhushan Agarwal, Cho Yan Joan. Wong, Tanishka Pillai, Thea Natasha Thirlwell, Wing Nam Leung, Colman Tse, Yan Tung Li, Bo Ley Cheng, Hill Yan Cedar. Chan, and Gilad Feldman. 2021. Agency and Self-other Asymmetries in Perceived Bias and Shortcomings: Replications of the Bias Blind Spot and Link to Free Will Beliefs. Judgment and Decision Making 16 (6): 1392–1412.

Channel 4 News. 2013. Jordan Peterson debate on the gender pay gap, campus protests and postmodernism. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aMcjxSThD54.

Davidson, Donald. 2001. Inquiries into Truth and Interpretation. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Davidson, Donald. 1991. "Three varieties of knowledge." In Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement, edited by A. Phillips Griffiths, 153–66. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dennett, Daniel. 2013. Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking. New York: W. W. Norton Company.

Gilovich, Thomas. 1991. How We Know What Isn’t So. New York: The Free Press.

Govier, Trudy. 2018. Problems in Argument Analysis and Evaluation. 2nd edition. Windsor: Windsor Studies in Argumentation. 1987.

Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Vintage Books.

Hautli-Janisz, Annette, Katarzyna Budzynska, Conor McKillop, Brian Plüss, Valentin Gold, and Chris Reed. 2022. Questions in Argumentative Dialogue. Journal of Pragmatics 88: 56–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.10.029.

IDEASxP&G. 2015. Neil Bearden—Principle of Charity. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y9KcgVu-QRI. Accessed 25 Aug 2021.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lewiński, Marcin. 2012. The Paradox of Charity. Informal Logic 32 (4): 403–439. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v32i4.3620.

Loyola, Ignatius. 1992. The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius. Translated by George E. Ganss. St. Louis: Institute of Jesuit Sources.

Macagno, Fabrizio, and Douglas Walton. 2017. Interpreting Straw Man Argumentation: The Pragmatics of Quotation and Reporting. Amsterdam: Springer.

Pronin, Emily, and Matthew B. Kugler. 2007. Valuing Thoughts, Ignoring Behavior: The Introspection Illusion as a Source of the Bias Blind Spot. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43 (4): 565–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.05.011.

Pronin, Emily, Daniel Y. Lin, and Lee Ross. 2002. The Bias Blind Spot: Perceptions of Bias in Self-versus Others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 28: 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202286008.

Pronin, Emily, Thomas Gilovich, and Lee Ross. 2004. Objectivity in the Eye of the Beholder: Divergent Perceptions of Bias in Self Versus Others. Psychological Review 111 (3): 781–799. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.111.3.781.

Quine, Willard van Orman 2013. Word and Object. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England: The MIT Press.

Stevens, Katharina. 2021. Charity for Moral Reasons?—A Defense of the Principle of Charity in Argumentation. Argument and Advocacy 57 (2): 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511431.2021.1897327.

Stevens, Katharina. 2021b. Fooling the Victim: Of Straw Men and Those Who Fall for Them. Philosophy & Rhetoric 54 (2): 109–127. https://doi.org/10.5325/philrhet.54.2.0109.

Stroud, Scott R. 2017. Rhetoric, Ethics, and the Principle of Charity: Pragmatist Clues to the Democratic Riddle. Language & Dialogue 7 (1): 26–44. https://doi.org/10.1075/ld.7.1.03str.

Talmudology. 2015. Rabbi Meir on Maximizing Meaning. http://www.talmudology.com/jeremybrownmdgmailcom/2015/3/29/ketuvot-58b-meaning. Accessed 25 Aug 2021.

Thagard, Paul, and Richard E. Nisbett. 1983. Rationality and Charity. Philosophy of Science 50 (2): 250–267.

Van Eemeren, FH., and R Grootendorst. 1995. "The Pragma-Dialectical Approach to Fallacies." In Fallacies: Classical and Contemporary Readings, edited by Hans V. Hansen and Robert C. Pinto, 130–44.

Eemeren, FH., and R Grootendorst. 2004. A systematic theory of argumentation. The pragma-dialected approach. Camrbidge: Cambridge University Press.

Van Eemeren, F.H., and R. Grootendorst. 2003. A Pragma-Dialectical Procedure for a Critical Discussion. Argumentation 17: 365–386.

Walton, Douglas. 2000. New Dialectical Rules for Ambiguity. Informal Logic 20 (3): 261–274.

Wilson, Neil L. 1959. Substances Without Substrata. The Review of Metaphysics 12 (4): 521–539.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pruś, J., Sikora, P. The Dialectical Principle of Charity: A Procedure for a Critical Discussion. Argumentation 37, 577–600 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-023-09615-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-023-09615-8