Abstract

Falls among older adults are influenced by both physical and psychological risk factors. This pilot study specifically examined the impact of integrating Dance/Movement Therapy (DMT) into a regimen of physical therapy exercises (PTE) for fall prevention. The primary objectives included examining the effect of post-PTE+DMT intervention on heart rate variability (HRV), a psychophysiological marker, and fall risk factors. Additionally, this study aimed to examine correlations between HRV and levels of fall risk. Eight community-dwelling older adults (median = 83 [interquartile ranges: 80.5–85.75]) from a day center for senior citizens were randomly assigned to either a PTE+DMT group or a PTE group. A post intervention battery of HRV, physical and psychological fall risk assessments, was conducted. The results of nonparametric analysis demonstrated the potential impact of the PTE+DMT intervention in improving balance and self-efficacy measures related to falls when compared to participation in PTE alone. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups in term of HRV and other physical and psychological fall risk factors. The emerging trends in the associations between HRV, fall risk, and balance levels suggest the potential utility of HRV as an objective psychophysiological marker for assessing fall risk levels. Moreover, the results underscore the potential advantages of interventions that integrate both physical and psychological components to mitigate fall risk in older adults, emphasizing the intricate mind–body connection.

The ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05948735, July 7, 2023.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Falls are a prominent cause of unintentional mortality globally and a major contributor to morbidity among the older adult population (World Health Organization, 2021a). Falls can result in severe consequences, such as physical and psychological harm, diminished quality of life and loss of independence (Ganz & Latham, 2020; Pereira et al., 2020). Research underscores the complexity of falls in older adults, influenced by a combination of intrinsic factors (patient-related), extrinsic factors (environment-related), and behavioral aspects (activity-related) (World Health Organization, 2021b). Among these, intrinsic factors can be classified into physical and psychological factors, which significantly impact falls (Yi et al., 2022). Physical factors encompass an age-related reduction in balance, muscle strength, sensory functions, and walking abilities (Li et al., 2023; Qian et al., 2021). Psychological factors include fall-related psychological concerns such as fear of falling (FOF) (Lenouvel et al., 2022; Pauelsen et al., 2020), falls self-efficacy (FSe; confidence in executing daily tasks without falling) (Pauelsen et al., 2020), and depression (Gambaro et al., 2022).

There are numerous structured, effective fall prevention programs that are conceptualized and practically designed to reduce physical fall risk factors, such as decreased balance, through the incorporation of physical exercise (Sherrington et al., 2019). However, a notable drawback in many of these programs is the neglect of psychological issues which predict falls. This constrained approach likely hinders the effectiveness of these programs due to the untreated aspects of certain fall risk factors (Lee & Yu, 2020).

Dance/Movement Therapy for Fall Prevention

The researchers of this study have proposed, in prior studies, an innovative intervention, a distinctive integration of physical therapy exercise (PTE) with Dance/Movement Therapy (DMT), designed to address both physical and psychological fall risk factors among older adults (Pitluk Barash et al., 2023a, 2023b). Findings of these studies demonstrate the feasibility of this intervention and its potential benefits in enhancing balance and reducing FOF compared to PTE only. This unique conceptual and practical approach synthesizes the principles of PTE and DMT to provide a more comprehensive solution for fall prevention.

As a mental health profession, DMT recognizes that physical, emotional, cognitive, and perceptual aspects are interrelated in the experience of the self and invites the emotional processing of a physical experience with the goal of enhancing health and mental wellbeing (American Dance Therapy Association, 2021). This therapeutic approach emphasizes that the body and mind are not separate entities (Rosendahl et al., 2021), and that human experiences are embodied, internalized, and presented in the body (Standal, 2020). Previous research has shown that body movements and postures can trigger emotions, aid in their identification, and regulate emotional experiences (Melzer et al., 2019; Shafir et al., 2016). Both extensive theoretical (Bräuninger, 2014; de Tord & Bräuninger, 2015) and clinical (Capello, 2018) data have shown that the unique framework of this treatment allows physical activity to adapt to the physical, emotional, and social needs and limitations of an older person. In DMT, the therapist’s sensitive attunement to an individual’s spontaneous movement serves to encourage its expansion and encounter its resources; hence, it represents a source for experiencing the renewal and development of mental resilience in old age (Capello, 2018). Previous studies have shown that DMT decreases depression, anxiety, and negative mood and increases quality of life in older adults (Ho et al., 2020; Koch et al., 2019b; Shuper Engelhard, 2020). In addition, several studies have found that group DMT yields positive physiological, functional, and psychological outcomes in older adults with dementia (Ho et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2022), Parkinson’s disease (Fisher et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2022), and psychiatric conditions (Jiménez et al., 2019).

Grounding techniques of DMT focus on stability and balance and are based on psychosomatics, positing that physical and emotional processes are intertwined (Pitluk et al., 2021; Shuper Engelhard et al., 2021). The perception of the position of the body parts in space, balance, and the tactile system promote the processing of an emotional experience arising through physical movement. Empathetic therapists who are attentive to the patient’s needs and the therapist–patient relationship facilitate this process (Norcross & Lambert, 2018). Grounding techniques can be applied in a group format, with evidence from clinical examples suggesting positive effects on creating mutual relationships between group members, fostering social empowerment, and reducing the feeling of loneliness (de Tord & Bräuninger, 2015; Havsteen-Franklin et al., 2019).

The Present Study

As part of a broader study, the current pilot study examined the impact of integrating DMT into physical exercise on heart rate variability (HRV), a psychophysiological marker, as a potential mediating factor in addressing both physical and psychological fall risk factors. This measure, which delineates fluctuations in the intervals between normal heartbeats (Pham et al., 2021), is a marker for cardiac vagal tone and reflects the parasympathetic nervous system’s role in cardiac regulation. Higher HRV is associated with enhanced self-regulation at cognitive, emotional, social, and health levels (Laborde et al., 2017). Studies have shown that lower HRV correlates with depression (Koch et al., 2019a) and predicts fall risk in hypertensive older adults (Castaldo et al., 2017) and institutionalized older adults with mild cognitive impairment (Suh, 2023). To our knowledge, there is a lack of investigations into the impact of fall prevention programs that include both PTE and DMT on HRV. Furthermore, no prior studies have explored the association between HRV and fall risk factors among community-dwelling older adults, except for one dissertation that indicated declines in postural control and vestibular function associated with alterations in HRV (Higgins, 2022).

The primary objectives of this study were as follows:

-

1.

To examine differences in HRV, and physical and psychological fall risk factors post-intervention between two intervention groups (PTE+DMT group versus PTE group).

-

2.

To assess correlations between HRV and the level of fall risk among community-dwelling older adults post-intervention.

-

3.

To examine correlations between HRV and the levels of both physical (balance) and psychological (FOF, FSe, depression) fall risk factors in community-dwelling older adults post-intervention.

Methodology

This pilot study employed a two-group, parallel randomized controlled trial (RCT) design. Simple randomization assignment was achieved using a random number table. Half the participants received PTE only, the other half received PTE+DMT. For this pilot study, we only report post-intervention measures of HRV, and physical and psychological fall risk factors, due technical and budgetary considerations.

Participants

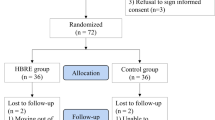

Fifteen participants were recruited for the study from a day center for senior citizens through convenience sampling by a social worker who was not involved in the intervention process. Inclusion criteria required participants to be community-dwelling older adults aged 65 years or older, capable of walking independently for at least 10 m, with or without the use of an assistive device. Additionally, participants needed to demonstrate the ability to walk for 2 min without any assistive device. Exclusion criteria comprised individuals with heart disease or respiratory disease, a history of stroke, Parkinson’s disease, or any other neurological disorder affecting walking. Exclusion criteria also included individuals with blindness or deafness that might impede safe walking and following instructions, individuals with vestibular disorder such as vertigo, acute joint or musculoskeletal pain in the lower limbs, limiting continuous walking for 2 min, and those with significant sensory impairments in the lower limbs. Of the initial 15 participants who agreed to participate, 12 participants were ultimately deemed suitable for the study according to the eligibility criteria. Three participants withdrew after a single intervention session due to extended illness. One participant opted not to participate before the intervention began. Eight participants (four in each group) were included in the following analyses (See Fig. 1).

Interventions-PTE+DMT and PTE

Intervention setting: the interventions were conducted in a 36 m2 (387.5 square feet) room, suitable for movement in the space, within the day center. The room was arranged with chairs in a circular formation.

Intervention structure: both groups engaged in 12 group sessions, with each session lasting 45 min. These sessions occurred twice a week over the course of 6 weeks. In the PTE+DMT group, six of the sessions lasted 50 min. Both groups performed the same OEP exercises, however, the PTE+DMT group occasionally performed fewer repetitions. These modifications were due to the integration of elements from DMT, as described below.

Intervention description: both groups participated in a program based on the Otago Exercise Program (OEP) (Campbell et al., 1997; Chiu et al., 2021). The OEP is a widely accepted physical therapy (PT) program for fall prevention that has been proven effective among older adults, which included a structured sequence of exercises (Peng et al., 2023). These exercises increased in complexity on a weekly basis, adhering to the following structure: an 8-min warm-up, 10-min of strength exercises, 20-min of balance exercises, and a 7-min cool-down.

PTE+DMT group: in addition to PTE, the PTE+DMT group underwent an intervention that seamlessly integrated techniques from the OEP and DMT. This approach aimed to address the emotional aspects that may arise during physical exercise. The supplement of DMT included the following components: 8-min warm-up based on the OEP protocol during which the therapist directed the participants to pay attention to their somatic experience, quality of movement, rhythm, muscle tension, transfer of weight, and breathing. The objective of the warm-up stage was to promote relaxation and reduce distractions from daily experiences, attaining availability to the therapeutic process, practicing somatic listening techniques, and deepening the awareness of feelings associated with the sensory experience. The core component of the DMT intervention involved “expressive movement,” which was integrated with the OEP protocol, including 10-min strength exercises and 20-min balance exercises. This was achieved by focusing on the dynamic aspects of the participants’ movements using the following operational ingredients:

-

1.

The therapist encouraged the participants to attend to sensations, emotions, images, experiences, memories, and associations that arose following different movements. For example, during an exercise when participants raised onto their tiptoes from a standing position, the instructor prompted them to focus on their gaze direction, back posture, and any mental imagery that may have emerged during the exercise.

-

2.

The therapist encouraged the participants to expand the exercise with spontaneous movements expressing diverse feelings and emotions. They were encouraged to reach these goals by experiencing different rhythms, using different forces, personal space, and muscle contraction and relaxation.

-

3.

Mirroring movement and synchronization—participants were encouraged to mirror the movement characteristics of other group members in terms of rhythm/speed/intensity, etc. The goal was to become exposed to the body stories through ‘kinesthetic empathy’ and to contribute to the sense of visibility and group cohesion.

-

4.

Invitation for verbal reflection and sharing the “here and now” experience—the participants were encouraged to share feelings, sensations, and thoughts that emerged during movement (e.g., familiarity, strangeness, emotions, memories, etc.).

The end of the session included a 7-min cool-down period of body relaxation and the therapist’s summary of the emotional issues that emerged during the meeting.

The groups were led by a dance movement therapist who received supervision from two experts in DMT and PTE, both with over 20 years of experience. The therapist had also undergone training in OEP. To ensure fidelity to the interventions, the instructor completed a treatment fidelity questionnaire after each session, confirming adherence to the required intervention protocol.

Measurement

Participant Characteristics

A self-report questionnaire was used to collect data on demographic characteristics and clinical information, which included details such as age, marital status, medications, and background illnesses.

HRV

The HRV analysis was conducted based upon the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) between normal heartbeats in milliseconds. RMSSD is a recognized marker of vagal tone, and it is considered to be less influenced by respiration compared to frequency domain measures (Laborde et al., 2017). The median RMSSD in short-term HRV measures among healthy adults aged 18 and over was found to be 42 ms (range: 19–75 ms) (Nunan et al., 2010). A higher RMSSD index indicates better HRV. Data were collected using a photoplethysmograph finger sensor while patients were in a seated position, during daytime hours (10:00–12:00 AM). The data were collected using the “Ifeel Well” application (Ifeel Labs, Israel). This application has previously been utilized in research by Yerushalmy-Feler et al. (2022), to assess HRV as a predictor of clinical outcomes in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. The application was installed on a Galaxy S10e Android 11 device with an octa core 2.73 GHz processor and 6 GB of RAM.

Level of Fall Risk

Fall risk assessment was performed using the Fall Risk Questionnaire (FRQ), a self-report questionnaire with 12 items rated on a dichotomous scale (“yes” or “no”) (Rubenstein et al., 2011). The overall score is calculated by summing the items with a “yes” response, resulting in a score range from 0 to 14. A score of 4 or higher indicates a fall risk level warranting consultation with a healthcare provider. The English version of the FRQ has demonstrated internal consistency reliability and concurrent validity (α = .746; Kappa = .875, p < .0001).

Objective Balance

Objective balance assessments were performed using the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test (Podsiadlo & Richardson, 1991) and the Five Times Sit to Stand (5STS) test (Whitney et al., 2005). The TUG test measures the time participants take to rise from a chair (46 cm height), walk 3 m, turn, walk back, and sit down again. The TUG test was performed twice, and the average of the two scores determined the overall performance. A score exceeding 13.5 s indicates a fall risk for community-dwelling older adults (Shumway-Cook et al., 2000). The TUG test has demonstrated inter-rater reliability and convergent validity (ICC = .99; r = − .81) (Podsiadlo & Richardson, 1991).

In the 5STS test, the time taken by participants to transition from a seated position in a chair to standing up and sitting down five times was measured. Norm scores for ages 70 to 79 and 80 to 89 are 12.6 s and 14.8 s, respectively (Bohannon, 2006). The 5STS test has demonstrated test–retest reliability (ICC = .957) (Bohannon et al., 2007) and convergent validity (r = .918) (Schaubert & Bohannon, 2005).

FOF

Assessment of FOF was performed using the FOF single item question (FOF SIQ) (Lachman et al., 1998), which is a single self-report question: “Are you afraid of falling?” The question is rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (no, not afraid) to 4 (yes, indeed afraid). The English version of the question has demonstrated convergent validity (r = − .59).

FSe

Assessment of FSe was performed using the Short Falls Efficacy Scale-International (Short FES-I), which is a self-report questionnaire that includes seven items rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all concerned) to 4 (extremely concerned) (Kempen et al., 2008). The overall score of the questionnaire is the sum of its items, and the score range is between 7 and 28. A lower score indicates better self-efficacy related to falls. The English version of the questionnaire has demonstrated test–retest reliability and convergent validity (α = .92; ρ = .97).

Depression

Depression was assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a self-report questionnaire consisting of 9 items that list major depressive symptoms according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Kroenke et al., 2001). Participants rated their experience on a 4-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). For example, a question asks, “Over the last two weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling tired or having little energy?” The overall score is the sum of the items, ranging from 0 to 27, with a higher score indicating a higher level of distress and depression. Scores of 0 to 4 indicate no depression symptoms, scores of 5 to 9 indicate mild depression symptoms, scores of 10 to 14 indicate moderate depression symptoms, scores of 15 to 19 indicate moderate to severe depression symptoms, and scores of 20 to 27 indicate severe depression symptoms. The Hebrew version of the questionnaire has demonstrated internal consistency reliability (α = .82) among community-dwelling older adults (Ayalon et al., 2010).

Procedure

All participants received both written and verbal explanations regarding the study, followed by providing their written informed consent before any evaluations. Prior to the intervention, participants completed a self-report questionnaire to provide demographic and clinical information. Participants were then randomly assigned to either the PTE+DMT group or PTE. Following the last intervention session, participants rested for 5 to 10 min for HRV recording. They were instructed to sit quietly, breathe regularly, and avoid speaking or moving during the recording. A one-min measurement was then recorded to assess HRV. Within a week after the intervention’s conclusion, all participants completed self-report questionnaires to assess physical and psychological fall risk factors. If necessary, participants received assistance in reading the questions to ensure consistent presentation and account for varying levels of vigilance and attentiveness. This approach aimed to prevent potential bias among participants. Additionally, objective measurements were performed to assess participants’ balance levels.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including medians and interquartile ranges, were calculated for the primary characteristics and outcome measures of all participants. In order to examine differences in HRV and fall risk factors post-intervention between the groups, one-tailed Mann/Whitney U test analyses were performed. To assess correlations between HRV and fall risk factors, a one-tailed Spearman correlation was calculated. Correlation values of 0 < r < .1 are considered to indicate a negligible correlation, values of .1 < r < .39 indicate a weak correlation, values of .4 < r < .69 indicate a moderate correlation, values of .7 < r < .89 indicate a strong correlation, and a very strong correlation is indicated by values of .9 < r < 1 (Schober et al., 2018). All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and significance was determined at p values ≤ .05.

Results

Participants

Eight participants (six women and two men), between ages 77 and 88 years (median = 83 [interquartile ranges: 80.5–85.75]) participated in the study. Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics of participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics in each group.

Post-intervention Between Groups Differences

Table 2 displays the post-intervention differences between the PTE+DMT group and the PTE group. Following the intervention, no significant differences were observed in RMSSD scores between the groups. The PTE+DMT group achieved a significantly lower 5STS score (i.e., higher balance) compared to the PTE group (U = 2, p < .05). In addition, the PTE+DMT group exhibited a significantly lower Short FES-I score (i.e. higher FSe) than the PTE group (U = 0, p < .01). No other significant differences in outcome variables were observed between the groups.

The Levels of Fall Risk and HRV Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults

The participants’ FRQ score indicated a risk of falling (median = 7 [interquartile range = 3.75–9.75]). The participants’ RMSSD score indicated a low value of HRV (median = 14.46 [interquartile range = 8.97–25.89]), as would be expected from older adults.

Correlations Between HRV and the Level of Fall Risk

The results revealed a moderate negative correlation between lower RMSSD level and higher fall risk level, although it showed only a trend for statistical significance (r = − .59, p = .06) (refer to Fig. 2).

Correlations Between HRV and the Levels of Physical and Psychological Fall Risk Factors

Table 3 displays the results of descriptive analysis, including median and interquartile range, and Spearman correlation analysis between HRV and physical and psychological fall risk factors. The results revealed a moderate negative correlation between lower RMSSD level and higher TUG level (r = − .57, p = .07), although it showed only a trend for statistical significance (refer to Fig. 3). No other significant correlations between the variables were observed.

Discussion

The present study explored the effects of a fall prevention program which integrates PTE and DMT on HRV and factors contributing to fall risk in older adults. The findings revealed that the integrated PTE and DMT intervention had a potential positive effect on balance and muscle strength, as indicated by the 5STS test score, in the PTE+DMT group compared to the PTE group alone. These results are consistent with those of our previous pilot study, which involved older women participating in six sessions of the PTE+DMT intervention (Pitluk Barash et al., 2023b). In that study, a notable difference in balance outcome was observed between the integrated intervention group and the PTE-only group. These current findings emphasize the comprehensive nature of DMT, reinforcing the well-established, bidirectional relationship between mental and physical states (American Dance Therapy Association, 2021; Koch et al., 2019b). Additionally, interventions based on dance often incorporate key movement elements found in DMT, such as rhythm, synchronization, and spontaneity. These have been acknowledged for their benefits in addressing physical risk factors related to falls in older adults. These interventions have demonstrated positive effects on mobility functions and endurance performance in healthy older individuals (Liu et al., 2021). They have also been effective in improving balance and walking abilities in older adults with various health conditions (Hackney et al., 2013; Hewston et al., 2023; Ismail et al., 2021).

The current study’s findings showed a potential positive impact on FSe, as measured by the FES-I score, in the PTE+DMT group compared to the PTE group. This highlights the importance of integrating emotional therapy alongside physical activity to effectively address both physical and psychological fall risk factors. In support of this approach, a recent qualitative study by Haynes et al. (2023) focused on a dance program tailored for older individuals. This program not only aimed to improve physical and mental health but also incorporated engaging dance sequences with evidence-based fall prevention strategies. The study’s findings indicate that participating in dance not only fosters increased self-efficacy but also could extend these benefits beyond the dance setting, such as in FSe. Furthermore, clinical cases demonstrate that grounding techniques, commonly utilized in DMT, contribute to enhance physical awareness, improved sensory perception, and consequently strengthen sense of security (de Tord & Bräuninger, 2015). This aligns with Bandura’s social cognitive theory, which posits that self-efficacy, encompassing control and security, significantly influences emotional, cognitive, and behavioral patterns across various psychosocial and physical functional areas (Bandura, 1997). Additionally, a strong sense of self-efficacy has been linked to improved balance (McCarty et al., 2021), corroborating the current study’s observation of increased FSe and enhanced balance abilities among participants in the PTE+DMT group.

The study observed a trend toward a moderate negative correlation between HRV, as measured by the RMSSD, and fall risk level, though this was not statistically significant (p = .06). This trend aligns with previous research identifying correlations between HRV and the risk of falls (Castaldo et al., 2017; Suh, 2023), thereby reinforcing HRV’s potential as an objective psychophysiological marker for assessing fall risk. Accurate fall risk assessment is vital for customizing treatment strategies and preventative efforts, considering all contributing factors (Strini et al., 2021). Additionally, there was a similar trend indicating a moderate negative correlation between HRV (RMSSD) and balance and gait abilities, as measured by the TUG test score (p = .07). This is in line with a previous study of 77 older adults in a senior housing community, which found that higher HRV significantly correlated with lower TUG scores, suggesting better functional status (Graham et al., 2019). Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to determine if these trends reach statistical significance, and should explore additional correlations and effects resulting from interventions which integrate physical and psychological components.

The current study has several limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the results and in guiding future research. One major limitation is the small sample size, which may be highly sensitive to variability among participants and inevitably restricts the scope of statistical analyses as well as the statistical significance of the findings. Expanding the sample size in future studies would enable more robust parametric analyses, leading to a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the subject. Additionally, this study focused solely on post-test outcomes and did not employ a pre-post intervention research design. This was due to the nature of the intervention groups beginning their participation within a broader study framework. As such, caution is advised in drawing definitive conclusions from the results. Nevertheless, the use of random assignment in this study aimed to minimize potential differences between groups prior to the initiation of intervention, but after randomization.

Practical Implication

The integration of structured physical exercise instructions with open instructions that encourage the expression of emotional experiences during physical activities, is significant for highlighting psychological aspects related to falling (Pitluk Barash et al., 2023a). Achieving open instructions involves the therapist addressing the content brought forth by the patient, a process known as “picking up.” This concept, fundamental to DMT and first introduced by Chace, refers to the therapist’s ability to integrate patients’ spontaneous movements and expressions into the therapy session and respond to them effectively (Imus & Young, 2023; Sandel et al., 1993). Previous focus group findings suggest that the efficacy of dance interventions in reducing fall risk can be maximized by combining creative and didactic dance elements (Britten et al., 2017). Therefore, a semi-structured approach which integrates exercises grounded in physiological principles for balance improvement with movements focused on experiential aspects may present an optimal strategy for fall prevention. This approach allows for both the necessary physical training and the emotional expression, possibly crucial for comprehensive fall risk prevention.

This study highlights the importance of HRV in providing the necessary scientific evidence and framework for exploring and understanding the psychophysiological mechanisms that connect psychological factors to physical outcomes, such as falls. Future research with larger sample sizes is expected to yield a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between physical and psychological factors which contribute to fall risk. Future studies with a larger sample size as well as pre–post intervention research design can also perform better statistical mediation analyses to examine whether the benefits of adding DMT to PTE on balance-related outcomes are due to vagal nerve activation (HRV) and/or due to reducing psychological fall risk factors. Additionally, while our pilot study’s small sample size limits the power to detect statistically significant differences, future studies that calculate effect sizes could provide valuable information about the magnitude of the intervention’s impact. Effect size measures can quantify the strength of the relationship between the intervention and outcomes (HRV and fall risk factors), offering a clearer understanding of the potential clinical relevance of our intervention, even in the absence of statistical significance. These studies could offer biologically and psychologically plausible explanations for the ways in which fall prevention programs might influence both physical and psychological factors.

Conclusion

The results indicated the potential impact of the PTE+DMT intervention in enhancing balance and self-efficacy related to falls, compared to participating in PTE alone. However, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups in terms of HRV and other physical and psychological fall risk factors. The observed trends in the relationships between HRV, fall risk, and balance levels highlight the potential of HRV as an objective psychophysiological marker for assessing fall risk levels and its contributing factors. Additionally, the findings underscore the potential advantages of interventions that integrate physical and psychological components in reducing fall risk among older adults, thereby highlighting the complex interplay between the body and the mind.

Data Availability

The data are available upon reasonable request.

References

American Dance Therapy Association. (2021). What is dance/movement therapy? Retrieved December 30, 2022, from https://adta.memberclicks.net/

Ayalon, L., Goldfracht, M., & Bech, P. (2010). ‘Do you think you suffer from depression?’ Reevaluating the use of a single item question for the screening of depression in older primary care patients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(5), 497–502. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2368

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Bohannon, R. W. (2006). Reference values for the five-repetition sit-to-stand test: A descriptive meta-analysis of data from elders. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 103(1), 215–222. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.103.1.215-222

Bohannon, R. W., Shove, M. E., Barreca, S. R., Masters, L. M., & Sigouin, C. S. (2007). Five-repetition sit-to-stand test performance by community-dwelling adults: A preliminary investigation of times, determinants, and relationship with self-reported physical performance. Isokinetics and Exercise Science, 15, 77–81. https://doi.org/10.3233/IES-2007-0253

Bräuninger, I. (2014). Dance movement therapy with the elderly: An international Internet-based survey undertaken with practitioners. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 9(3), 138–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/17432979.2014.914977

Britten, L., Addington, C., & Astill, S. (2017). Dancing in time: Feasibility and acceptability of a contemporary dance programme to modify risk factors for falling in community dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0476-6

Campbell, A. J., Robertson, M. C., Gardner, M. M., Norton, R. N., Tilyard, M. W., & Buchner, D. M. (1997). Randomised controlled trial of a general practice programme of home based exercise to prevent falls in elderly women. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 315(7115), 1065–1069.

Capello, P. P. (2018). Dance/movement therapy and the older adult client: Healing pathways to resilience and community. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 40(1), 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-018-9270-z

Castaldo, R., Melillo, P., Izzo, R., De Luca, N., & Pecchia, L. (2017). Fall prediction in hypertensive patients via short-term HRV analysis. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 21(2), 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1109/jbhi.2016.2543960

Chiu, H. L., Yeh, T. T., Lo, Y. T., Liang, P. J., & Lee, S. C. (2021). The effects of the Otago Exercise Programme on actual and perceived balance in older adults: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 16(8), e0255780. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255780

de Tord, P., & Bräuninger, I. (2015). Grounding: Theoretical application and practice in dance movement therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 43, 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2015.02.001

Fisher, M., Kuhlmann, N., Moulin, H., Sack, J., Lazuk, T., & Gold, I. (2020). Effects of improvisational dance movement therapy on balance and cognition in Parkinson’s disease. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 38(4), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703181.2020.1765943

Gambaro, E., Gramaglia, C., Azzolina, D., Campani, D., Molin, A. D., & Zeppegno, P. (2022). The complex associations between late life depression, fear of falling and risk of falls. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 73, 101532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2021.101532

Ganz, D. A., & Latham, N. K. (2020). Prevention of falls in community-dwelling older adults. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(8), 734–743. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1903252

Graham, S. A., Jeste, D. V., Lee, E. E., Wu, T.-C., Tu, X., Kim, H.-C., & Depp, C. A. (2019). Associations between heart rate variability measured With a wrist-worn sensor and older adults’ physical function: Observational study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 7(10), e13757. https://doi.org/10.2196/13757

Hackney, M. E., Hall, C. D., Echt, K. V., & Wolf, S. L. (2013). Dancing for balance: Feasibility and efficacy in oldest-old adults with visual impairment. Nursing Research, 62(2), 138–143. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0b013e318283f68e

Havsteen-Franklin, D., Haeyen, S., Grant, C., & Karkou, V. (2019). A thematic synthesis of therapeutic actions in arts therapies and their perceived effects in the treatment of people with a diagnosis of cluster B personality disorder. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 63, 128–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2018.10.001

Haynes, A., Tiedemann, A., Hewton, G., Chenery, J., Sherrington, C., Merom, D., & Gilchrist, H. (2023). “It doesn’t feel like exercise”: A realist process evaluation of factors that support long-term attendance at dance classes designed for healthy ageing. Frontiers in Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1284272

Hewston, P., Bray, S. R., Kennedy, C. C., Ioannidis, G., Bosch, J., Marr, S., Hanman, A., Grenier, A., Hladysh, G., & Papaioannou, A. (2023). Does GERAS DANCE improve gait in older adults? Aging and Health Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahr.2023.100120

Higgins, L. Q. (2022). Heart rate variability as an assessment of fall risk in older adults (Publication Number 29256857) [Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/heart-rate-variability-as-assessment-fall-risk/docview/2718150381/se-2?accountid=14544

Ho, R. T. H., Fong, T. C. T., Chan, W. C., Kwan, J. S. K., Chiu, P. K. C., Yau, J. C. Y., & Lam, L. C. W. (2020). Psychophysiological effects of dance movement therapy and physical exercise on older adults with mild dementia: A randomized controlled trial. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(3), 560–570. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby145

Imus, S. D., & Young, J. (2023). Aesthetic mutuality: A mechanism of change in the creative arts therapies as applied to dance/movement therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 83, 102022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2023.102022

Ismail, S. R., Lee, S. W. H., Merom, D., Kamaruddin, P. S. N. M., Chong, M. S., Ong, T., & Lai, N. M. (2021). Evidence of disease severity, cognitive and physical outcomes of dance interventions for persons with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02446-w

Jiménez, J., Bräuninger, I., & Meekums, B. (2019). Dance movement therapy with older people with a psychiatric condition: A systematic review. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 63, 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2018.11.008

Kempen, G. I., Yardley, L., Van Haastregt, J. C., Zijlstra, G. R., Beyer, N., Hauer, K., & Todd, C. (2008). The Short FES-I: A shortened version of the falls efficacy scale-international to assess fear of falling. Age and Ageing, 37(1), 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afm157

Koch, C., Wilhelm, M., Salzmann, S., Rief, W., & Euteneuer, F. (2019a). A meta-analysis of heart rate variability in major depression. Psychological Medicine, 49(12), 1948–1957. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291719001351

Koch, S. C., Riege, R. F. F., Tisborn, K., Biondo, J., Martin, L., & Beelmann, A. (2019b). Effects of dance movement therapy and dance on health-related psychological outcomes. A meta-analysis update. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1806. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01806

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Laborde, S., Mosley, E., & Thayer, J. F. (2017). Heart rate variability and cardiac vagal tone in psychophysiological research—Recommendations for experiment planning, data analysis, and data reporting [Review]. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00213

Lachman, M. E., Howland, J., Tennstedt, S., Jette, A., Assmann, S., & Peterson, E. W. (1998). Fear of falling and activity restriction: The survey of activities and fear of falling in the elderly (SAFE). The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53(1), P43–P50. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/53B.1.P43

Lee, S. H., & Yu, S. (2020). Effectiveness of multifactorial interventions in preventing falls among older adults in the community: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 106, 103564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103564

Lenouvel, E., Novak, L., Biedermann, A., Kressig, R. W., & Kloppel, S. (2022). Preventive treatment options for fear of falling within the Swiss healthcare system: A position paper. Zeitschrift Für Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 55(7), 597–602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-021-01957-w. Praventive Behandlungsoptionen bei Sturzangst im Schweizer Gesundheitssystem : Ein Positionspapier.

Li, Y., Hou, L., Zhao, H., Xie, R., Yi, Y., & Ding, X. (2023). Risk factors for falls among community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Medicine. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1019094

Liu, X., Shen, P. L., & Tsai, Y. S. (2021). Dance intervention effects on physical function in healthy older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(2), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-019-01440-y

McCarty, K., Kennedy, W., Logan, S., & Levy, S. (2021). Examining the relationship between falls self-efficacy and postural sway in community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Kinesiology & Wellness, 10(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.56980/jkw.v10i.85

Melzer, A., Shafir, T., & Tsachor, R. P. (2019). How do we recognize emotion from movement? Specific motor components contribute to the recognition of each emotion. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1389. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01389

Norcross, J. C., & Lambert, M. J. (2018). Psychotherapy relationships that work III. Psychotherapy, 55, 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000193

Nunan, D., Sandercock, G. R. H., & Brodie, D. A. (2010). A quantitative systematic review of normal values for short-term heart rate variability in healthy adults. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 33(11), 1407–1417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02841.x

Pauelsen, M., Jafari, H., Strandkvist, V., Nyberg, L., Gustafsson, T., Vikman, I., & Roijezon, U. (2020). Frequency domain shows: Fall-related concerns and sensorimotor decline explain inability to adjust postural control strategy in older adults. PLoS ONE, 15(11), e0242608. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242608

Peng, Y., Yi, J., Zhang, Y., Sha, L., Jin, S., & Liu, Y. (2023). The effectiveness of a group-based Otago exercise program on physical function, frailty and health status in older nursing home residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatric Nursing, 49, 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.10.014

Pereira, C., Bravo, J., Raimundo, A., Tomas-Carus, P., Mendes, F., & Baptista, F. (2020). Risk for physical dependence in community-dwelling older adults: The role of fear of falling, falls and fall-related injuries. International Journal of Older People Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12310

Pham, T., Lau, Z. J., Chen, S. H. A., & Makowski, D. (2021). Heart rate variability in psychology: A review of HRV indices and an analysis tutorial. Sensors, 21(12), 3998.

Pitluk, M., Elboim-Gabyzon, M., & Shuper Engelhard, E. (2021). Validation of the grounding assessment tool for identifying emotional awareness and emotion regulation. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2021.101821

Pitluk Barash, M., Elboim-Gabyzon, M., & Shuper Engelhard, E. (2023a). Investigating the emotional content of older adults engaging in a fall prevention exercise program integrated with dance movement therapy: A preliminary study. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1260299

Pitluk Barash, M., Shuper Engelhard, E., & Elboim-Gabyzon, M. (2023b). Feasibility and effectiveness of a novel intervention integrating physical therapy exercise and dance movement therapy on fall risk in community-dwelling older women: A randomized pilot study. Healthcare, 11(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11081104

Podsiadlo, D., & Richardson, S. (1991). The timed “Up & Go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 39(2), 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x

Qian, X. X., Chau, P. H., Kwan, C. W., Lou, V. W. Q., Leung, A. Y. M., Ho, M., Fong, D. Y. T., & Chi, I. (2021). Investigating risk factors for falls among community-dwelling older adults according to WHO’s risk factor model for falls. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 25(4), 425–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1539-5

Rosendahl, S., Sattel, H., & Lahmann, C. (2021). Effectiveness of body psychotherapy. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 709798. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.709798

Rubenstein, L. Z., Vivrette, R., Harker, J. O., Stevens, J. A., & Kramer, B. J. (2011). Validating an evidence-based, self-rated fall risk questionnaire (FRQ) for older adults. Journal of Safety Research, 42(6), 493–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2011.08.006

Sandel, S. L., Chaiklin, S., & Lohn, A. (Eds.). (1993). Foundations of dance movement therapy: The life and work of Marian Chace. Marian Chace Memorial Fund of the American Dance Therapy Association.

Schaubert, K. L., & Bohannon, R. W. (2005). Reliability and validity of three strength measures obtained from community-dwelling elderly persons. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 19(3), 717–720. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-15954.1

Schober, P., Boer, C., & Schwarte, L. A. (2018). Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 126(5), 1763–1768. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000002864

Shafir, T., Tsachor, R. P., & Welch, K. B. (2016). Emotion regulation through movement: Unique sets of movement characteristics are associated with and enhance basic emotions. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02030

Sherrington, C., Fairhall, N. J., Wallbank, G. K., Tiedemann, A., Michaleff, Z. A., Howard, K., Clemson, L., Hopewell, S., & Lamb, S. E. (2019). Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1(1), CD012424. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012424.pub2

Shumway-Cook, A., Brauer, S., & Woollacott, M. (2000). Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go Test. Physical Therapy, 80(9), 896–903. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/80.9.896

Shuper Engelhard, E. (2020). Free-form dance as an alternative interaction for adult grandchildren and their grandparents. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00542

Shuper Engelhard, E., Pitluk, M., & Elboim-Gabyzon, M. (2021). Grounding the connection between psyche and soma: Creating a reliable observation tool for grounding assessment in an adult population. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 621958. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.621958

Standal, Ø. F. (2020). Embodiment: Philosophical considerations of the body in adaptive physical education. In J. A. Haegele, S. R. Hodge, & D. R. Shapiro (Eds.), Routledge handbook of adapted physical education (pp. 227–238). Routledge.

Strini, V., Schiavolin, R., & Prendin, A. (2021). Fall risk assessment scales: A systematic literature review. Nursing Reports, 11(2), 430–443.

Suh, M. (2023). Increased parasympathetic activity as a fall risk factor beyond conventional factors in institutionalized older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Asian Nursing Research, 17(3), 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2023.05.001

Whitney, S. L., Wrisley, D. M., Marchetti, G. F., Gee, M. A., Redfern, M. S., & Furman, J. M. (2005). Clinical measurement of sit-to-stand performance in people with balance disorders: Validity of data for the Five-Times-Sit-to-Stand Test. Physical Therapy, 85(10), 1034–1045. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/85.10.1034

World Health Organization. (2021a). Falls. Retrieved April 26, 2021, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls

World Health Organization. (2021b). Step safely: Strategies for preventing and managing falls across the life-course. World Health Organization.

Wu, C.-C., Xiong, H.-Y., Zheng, J.-J., & Wang, X.-Q. (2022). Dance movement therapy for neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.975711

Yerushalmy-Feler, A., Cohen, S., Lubetzky, R., Moran-Lev, H., Ricon-Becker, I., Ben-Eliyahu, S., & Gidron, Y. (2022). Heart rate variability as a predictor of disease exacerbation in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 158, 110911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.110911

Yi, D., Jang, S., & Yim, J. (2022). Relationship between associated neuropsychological factors and fall risk factors in community-dwelling elderly. Healthcare, 10(4), 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10040728

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the participants for their participation and interest. They would also like to extend their appreciation to Shalhevet day center management and team for their cooperation.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Haifa. This research was funded by the Marian Chace Foundation; the Emili Sagol Creative Arts Therapies Research Center (CATRC) at the University of Haifa; and Institutional Excellence Scholarships for Outstanding Doctoral Students Academic Year 2022–2023 Graduate Studies Authority at the University of Haifa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Michal Elboim-Gabyzon, Einat Shuper Engelhard, Yori Gidron, and Michal Pitluk Barash; Methodology: Michal Elboim-Gabyzon, Einat Shuper Engelhard, Yori Gidron, and Michal Pitluk Barash; Formal analysis and investigation: Michal Pitluk Barash, and Yori Gidron; Writing—original draft preparation: Michal Pitluk Barash; Writing—review and editing: Michal Elboim-Gabyzon, Einat Shuper Engelhard, and Yori Gidron; Funding acquisition: Michal Elboim-Gabyzon and Einat Shuper Engelhard; Supervision: Michal Elboim-Gabyzon, Einat Shuper Engelhard, and Yori Gidron.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel (Approval 2699).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pitluk Barash, M., Shuper Engelhard, E., Elboim-Gabyzon, M. et al. Effects of Physical Therapy Integrated with Dance/Movement Therapy on Heart Rate Variability and Fall-Related Variables: A Preliminary Controlled Trial. Am J Dance Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-024-09407-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-024-09407-x