Abstract

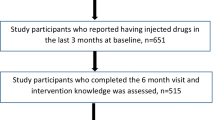

We sought to disentangle effects of the components of a peer-education intervention on self-reported injection risk behaviors among people who inject drugs (n = 560) in Philadelphia, US. We examined 226 egocentric groups/networks randomized to receive (or not) the intervention. Peer-education training consisted of two components delivered to the intervention network index individual only: (1) an initial training and (2) “booster” training sessions during 6- and 12-month follow up visits. In this secondary data analysis, using inverse-probability-weighted log-binomial mixed effects models, we estimated the effects of the components of the network-level peer-education intervention upon subsequent risk behaviors. This included contrasting outcome rates if a participant is a network member [non-index] under the network exposure versus under the network control condition (i.e., spillover effects). We found that compared to control networks, among intervention networks, the overall rates of injection risk behaviors were lower in both those recently exposed (i.e., at the prior visit) to a booster (rate ratio [95% confidence interval]: 0.61 [0.46–0.82]) and those not recently exposed to it (0.81 [0.67–0.98]). Only the boosters had statistically significant spillover effects (e.g., 0.59 [0.41–0.86] for recent exposure). Thus, both intervention components reduced injection risk behaviors with evidence of spillover effects for the boosters. Spillover should be assessed for an intervention that has an observable behavioral measure. Efforts to fully understand the impact of peer education should include routine evaluation of spillover effects. To maximize impact, boosters can be provided along with strategies to recruit especially committed peer educators and to increase attendance at trainings.

Clinical Trials Registration Clinicaltrials.gov NCT00038688 June 5, 2002.

Resumen

Intentamos desenmarañar los efectos de los componentes de una intervención de educación entre pares sobre los comportamientos de inyección de riesgo autorreportados entre personas que se inyectan drogas (n = 560; 226 grupos/redes egocéntricos(as)) aleatorizados(as) a recibir (o no) la intervención en Filadelfia, EUA. Dos componentes fueron administrados a índices de redes de intervención: una capacitación inicial y sesiones de “refuerzo” durante visitas de seguimiento. Usando modelos log-binomial de efectos mixtos ponderados por probabilidad inversa, estimamos los efectos de dichos componentes sobre los comportamientos de riesgo posteriores. Encontramos que en comparación con las redes control, en las redes de intervención, las tasas generales de comportamientos de inyección de riesgo fueron más bajas en ambas aquellas expuestas recientemente a un refuerzo (razón de tasas [intervalo de confianza del 95%]: 0.61 [0.46–0.82]) y aquellas no expuestas recientemente (0.81 [0.67–0.98]). Solamente los refuerzos tuvieron efectos derrame (i.e., contraste de las tasas de resultados si es miembro [no índice] de una red en una red con exposición reciente versus bajo la condición control) significativos (p. ej., 0.59 [0.41–0.86] para la exposición reciente).

Adapted from [14, 42]. To control for unmeasured baseline differences between indexes and non-indexes, the index effect (i.e., a contrast of the outcome rates under index status versus network member status if the network is a control network) is subtracted when estimating the direct and composite effects using the outcome model [14] [Buchanan et al. medRxiv 2022]

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

HPTN 037 Protocol can be found in the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) website https://www.hptn.org/research/studies/28. HPTN data might be available by request to the Statistical Center for HIV/AIDS Research and Prevention through the ATLAS Science Portal https://atlas.scharp.org/cpas/project/HPTN.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Latkin C, Friedman S. Drug use research: drug users as subjects or agents of change. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47(5):598–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2012.644177.

Ghosh D, Krishnan A, Gibson B, Brown SE, Latkin CA, Altice FL. Social network strategies to address HIV prevention and treatment continuum of care among at-risk and HIV-infected substance users: a systematic scoping review. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(4):1183–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1413-y.

Heckathorn DD, Broadhead RS, Anthony DL, Weakliem DL. AIDS and social networks: HIV prevention through network mobilization. Sociol Focus. 1999;32(2):159–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.1999.10571133.

Sergeyev B, Oparina T, Rumyantseva TP, et al. HIV prevention in Yaroslavl, Russia: a peer-driven intervention and needle exchange. J Drug Issues. 1999;29(4):777–804. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204269902900403.

Latkin CA, Sherman S, Knowlton A. HIV prevention among drug users: outcome of a network-oriented peer outreach intervention. Health Psychol. 2003;22(4):332–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.332.

Booth RE, Lehman WEK, Latkin CA, Brewster JT, Sinitsyna L, Dvoryak S. Use of a peer leader intervention model to reduce needle-related risk behaviors among drug injectors in Ukraine. J Drug Issues. 2009;39(3):607–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260903900307.

Latkin CA, Donnell D, Metzger D, et al. The efficacy of a network intervention to reduce HIV risk behaviors among drug users and risk partners in Chiang Mai, Thailand and Philadelphia, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(4):740–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.11.019.

Booth RE, Lehman WEK, Latkin CA, et al. Individual and network interventions with injection drug users in 5 Ukraine cities. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(2):336–43. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.172304.

Tobin KE, Kuramoto SJ, Davey-Rothwell MA, Latkin CA. The STEP into action study: a peer-based, personal risk network-focused HIV prevention intervention with injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addiction. 2011;106(2):366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03146.x.

Li J, Weeks MR, Borgatti SP, Clair S, Dickson-Gomez J. A social network approach to demonstrate the diffusion and change process of intervention from peer health advocates to the drug using community. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47(5):474–90. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2012.644097.

Hoffman IF, Latkin CA, Kukhareva PV, et al. A peer-educator network HIV prevention intervention among injection drug users: results of a randomized controlled trial in St. Petersburg, Russia. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2510–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0563-4.

Go VF, Frangakis C, Le Minh N, et al. Effects of an HIV peer prevention intervention on sexual and injecting risk behaviors among injecting drug users and their risk partners in Thai Nguyen, Vietnam: a randomized controlled trial. Soc Sci Med. 2013;96:154–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.006.

Latkin C, Donnell D, Liu TY, Davey-Rothwell M, Celentano D, Metzger D. The dynamic relationship between social norms and behaviors: the results of an HIV prevention network intervention for injection drug users. Addiction. 2013;108(5):934–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12095.

Buchanan AL, Vermund SH, Friedman SR, Spiegelman D. Assessing individual and disseminated effects in network-randomized studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(11):2449–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy149.

US National Institutes on Drug Abuse. Common comorbidities with substance use disorders research report. 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK571451/. Accessed 24 Mar 2023.

Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Colledge S, et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(12):e1192–e207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30375-3.

Strike C, Rudzinski K, Patterson J, Millson M. Frequent food insecurity among injection drug users: correlates and concerns. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1058. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-1058.

Marshall Z, Dechman MK, Minichiello A, Alcock L, Harris GE. Peering into the literature: a systematic review of the roles of people who inject drugs in harm reduction initiatives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;151:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.002.

Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood: Prentice Hall; 1977.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press; 1995.

Latkin CA, Knowlton AR. Social network assessments and interventions for health behavior change: a critical review. Behav Med. 2015;41(3):90–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2015.1034645.

Benjamin-Chung J, Arnold BF, Berger D, et al. Spillover effects in epidemiology: parameters, study designs and methodological considerations. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(1):332–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx201.

Collins LM, Kugler KC, Gwadz MV. Optimization of multicomponent behavioral and biobehavioral interventions for the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 1):S197–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1145-4.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, Group C. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):726–32. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232.

Latkin C, Celentano D, Metzger D. Protocol for HPTN 037 A phase III randomized study to evaluate the efficacy of a network-oriented peer education intervention for the prevention of HIV transmission among injection drug users and their network members: a study of the HIV Prevention Trials Network. 2003. https://www.hptn.org/sites/default/files/2016-05/HPTN037v2.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2023.

Lewis MA, DeVellis BM, Sleath B. Social influence and interpersonal communication in health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 240–64.

Turner JC. Social comparison and social identity: some prospects for intergroup behaviour. Eur J Social Psychol. 1975;5(1):1–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420050102.

Van Knippenberg D. Group norms, prototypicality, and persuasion. In: Terry DJ, Hogg MA, editors. Attitudes, behavior, and social context: the role of norms and group membership. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000. p. 157–70.

Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):550–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011.

Hernan MA, Brumback B, Robins JM. Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of HIV-positive men. Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):561–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-200009000-00012.

Wacholder S. Binomial regression in GLIM: estimating risk ratios and risk differences. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123(1):174–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114212.

Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. Hoboken: Wiley; 2012.

Skov T, Deddens J, Petersen MR, Endahl L. Prevalence proportion ratios: estimation and hypothesis testing. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27(1):91–. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/27.1.91. 5.

Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data-analysis using generalized linear-models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/73.1.13.

Huber PJ. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. Proc Fifth Berkeley Symp Math Statist Prob. 1967;1(1):13.

Cole SR, Hernan MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(6):656–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn164.

Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):199–200. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi188.

Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh090.

Miettinen OS. Theoretical epidemiology: principles of occurrence research in medicine. New York: Wiley; 1985.

Simmons N, Donnell D, Ou SS, et al. Assessment of contamination and misclassification biases in a randomized controlled trial of a social network peer education intervention to reduce HIV risk behaviors among drug users and risk partners in Philadelphia, PA and Chiang Mai, Thailand. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(10):1818–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-015-1073-3.

Aroke H, Buchanan A, Katenka N, et al. Evaluating the mediating role of recall of intervention knowledge in the relationship between a peer-driven intervention and HIV risk behaviors among people who inject drugs. AIDS Behav. 2023;27(2):578–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03792-5.

Halloran ME, Struchiner CJ. Study designs for dependent happenings. Epidemiology. 1991;2(5):331–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-199109000-00004.

Acknowledgements

R.U.H-R., A.L.B., and D.S. were supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01AI112339. R.U.H-R. and D.S. were also supported by NIH Grant P30MH062294. A.L.B. and D.S. were also supported by NIH Grant DP1ES025459. A.L.B. was also supported by NIH grant DP2DA046856. A.L.B, D.S., and L.F. were supported by NIH Grant R01MH134715. J.J.L. was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) DMS-1854934. We thank C.A.L. and Dr. Deborah Donnell for access to the HPTN 037 data. We also thank the study participants. Data from the HPTN 037 Study were obtained with support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the National Institute of Mental Health under NIH Grants UM1AI068619 (HPTN Leadership and Operations Center), UM1AI068617 (HPTN Statistical and Data Management Center), and UM1AI068613 (HPTN Laboratory Center). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the NSF.

Funding

National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: R01AI112339, P30MH062294, DP1ES025459, DP2DA046856, R01MH134715, UM1AI068619, UM1AI068617, and UM1AI068613. National Science Foundation, Grant/Award Number: DMS-1854934.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: All. Data analysis: RUH-R and ALB. Data interpretation: All. Writing of first draft of the manuscript: RUH-R. Revising the manuscript critically: All. Approval of final manuscript: All.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Ethical Approval

Approved by Yale University Institutional Review Board.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hernández-Ramírez, R.U., Spiegelman, D., Lok, J.J. et al. Overall, Direct, Spillover, and Composite Effects of Components of a Peer-Driven Intervention Package on Injection Risk Behavior Among People Who Inject Drugs in the HPTN 037 Study. AIDS Behav 28, 225–237 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-023-04213-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-023-04213-x