Abstract

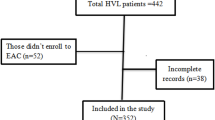

Little is known about clinical presentation and cascade of care among patients living with HIV (PLWH) in Beirut, Lebanon. The study aims to examine the reasons for HIV testing and to evaluate the clinical characteristics of, predictors of advanced HIV stage at presentation in, and rates of ART initiation, retention in care, and viral load suppression among PLWH in Lebanon. We conducted a retrospective study of PLWH presenting to a tertiary-care centre-affiliated outpatient clinic from 2008 to 2016 with new HIV infection diagnoses. We identified a total of 423 patients: 89% were men, 55% were 30–50 years old, and 58% self-identified as men who have sex with men. About 35% of the patients had concurrent sexually transmitted diseases at the time of HIV diagnosis. Thirty percent of infection cases were identified by provider-initiated HIV testing, 36% of cases were identified by patient-initiated testing, and 34% of patients underwent testing for screening purposes. The proportion of individuals presenting with advanced HIV disease decreased from 40% in 2008–2009 to 24% in 2014–2015. Age older than 50 years and identification of HIV by a medical provider were independent predictors of advanced HIV infection at presentation. Among patients having indications for treatment (n = 253), 239 (94%) were prescribed antiretroviral therapy, and 147 (58%) had evidence of viral suppression at 1 year. Furthermore, 266 patients (63%) were retained in care. The care continuum for PLWH in Lebanon is comparable with those in high-income countries yet still far behind the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 90–90–90 set target.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

UNAIDS. Fact sheet—Latest statistics on the status of the AIDS epidemic. 2016.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Data 2017. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20170720_Data_book_2017_en.pdf. Accessed 2 June 2018.

UNAIDS. Country factsheets LEBANON. 2016.

Heimer R, Barbour R, Khouri D, et al. HIV risk, prevalence, and access to care among men who have sex with men in Lebanon. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2017;33(11):1149–54.

Remien RH, Chowdhury J, Mokhbat JE, Soliman C, Adawy ME, El-Sadr W. Gender and care: access to HIV testing, care, and treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(Suppl 3):S106–110.

Kaplan RL, El Khoury C. The elephants in the room: sex, HIV, and LGBT populations in MENA. Intersectionality in Lebanon comment on "Improving the Quality and Quantity of HIV Data in the Middle East and North Africa: Key Challenges and Ways Forward". Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;6(8):477–9.

Mahfoud Z, Afifi R, Ramia S, et al. HIV/AIDS among female sex workers, injecting drug users and men who have sex with men in Lebanon: results of the first biobehavioral surveys. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 2):S45–54.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). AIDS-Defining Conditions. 2008.

WHO. Guidelines: HIV. HIV/AIDS Web site. https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/en/. Published 2018. Accessed 29 Apr 2018.

Ministry of Public Health. National AIDS Control Program in Lebanon. Ministry of Public Health. https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/2/4000/aids. Published 2018. Accessed 26 June 2018.

Mugavero MJ, Davila JA, Nevin CR, Giordano TP. From access to engagement: measuring retention in outpatient HIV clinical care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(10):607–13.

Labhardt ND, Bader J, Lejone TI, et al. Should viral load thresholds be lowered? Revisiting the WHO definition for virologic failure in patients on antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(28):e3985.

Jain V, Hartogensis W, Bacchetti P, et al. Antiretroviral therapy initiated within 6 months of HIV infection is associated with lower T-cell activation and smaller HIV reservoir size. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(8):1202–11.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505.

Dokubo EK, Shiraishi RW, Young PW, et al. Awareness of HIV status, prevention knowledge and condom use among people living with HIV in Mozambique. PLoS ONE. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12846.

Johnson AS, Heitgerd J, Koenig LJ, et al. Vital signs: HIV testing and diagnosis among adults-United States, 2001–2009 (reprinted from MMWR, vol 59, pg 1550–1555, 2010). J Am Med Assoc. 2011;305(3):244–6.

Miranda AC, Moneti V, Brogueira P, et al. Evolution trends over three decades of HIV infection late diagnosis: the experience of a Portuguese cohort of 705 HIV-infected patients. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(4 Suppl 3):19688.

Chkhartishvili N, Chokoshvili O, Bolokadze N, et al. Late presentation of HIV infection in the country of Georgia: 2012–2015. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10):e0186835.

Downing A, Garcia-Diaz JB. Missed opportunities for HIV diagnosis. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2017;16(1):14–7.

Fetene NW, Feleke AD. Missed opportunities for earlier HIV testing and diagnosis at the health facilities of Dessie town, North East Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:362.

Wanyenze RK, Kamya MR, Fatch R, et al. Missed opportunities for HIV testing and late-stage diagnosis among HIV-infected patients in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e21794.

Baral S, Turner RM, Lyons CE, et al. Population size estimation of gay and bisexual men and other men who have sex with men using social media-based platforms. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2018;4(1):e15.

Burke RC, Sepkowitz KA, Bernstein KT, et al. Why don't physicians test for HIV? A review of the US literature. AIDS. 2007;21(12):1617–24.

Dandachi D, Dang BN, Wilson Dib R, Friedman H, Giordano T. Knowledge of HIV testing guidelines among US internal medicine residents: A decade after the centers for disease control and prevention's routine HIV testing recommendations. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32(5):175–80.

Dokuzoguz B, Korten V, Gökengin D, et al. Transmission route and reasons for HIV testing among recently diagnosed HIV patients in HIV-TR cohort, 2011–2012. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(4 Suppl 3):19595.

Mutchler MG, McDavitt BW, Tran TN, et al. This is who we are: building community for HIV prevention with young gay and bisexual men in Beirut, Lebanon. Cult Health Sex. 2017; 20(6):1–14.

HIV self testing and partner notification. Supplement to consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services. Vol Supplement: World Health Organization; 2016.

Clark KA, Keene DE, Pachankis JE, Fattal O, Rizk N, Khoshnood K. A qualitative analysis of multi-level barriers to HIV testing among women in Lebanon. Cult Health Sex. 2017;19(9):996–1010.

Kaplan RL, Khoury CE, Field ERS, Mokhbat J. Living day by day: the meaning of living with HIV/AIDS among women in Lebanon. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2016;3:2333393616650082.

Wagner GJ, Tohme J, Hoover M, et al. HIV prevalence and demographic determinants of unprotected anal sex and HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Beirut, Lebanon. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(4):779–88.

Tohme J, Egan JE, Stall R, Wagner G, Mokhbat J. HIV prevalence and demographic determinants of unprotected anal sex and HIV testing among male refugees who have sex with men in Beirut, Lebanon. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(Suppl 3):408–16.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Understanding the HIV Care Continuum. 2017.

Kay ES, Batey DS, Mugavero MJ. The HIV treatment cascade and care continuum: updates, goals, and recommendations for the future. AIDS Res Ther. 2016;13:35 (eCollection 2016).

Funding

Not applicable. This research was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

We declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson Dib, R., Dandachi, D., Matar, M. et al. HIV in Lebanon: Reasons for Testing, Engagement in Care, and Outcomes in Patients with Newly Diagnosed HIV Infections. AIDS Behav 24, 2290–2298 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02788-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02788-3