Abstract

This paper interrogates afresh what the various Igbo-Ukwu site contexts, carefully examined and closely documented by Shaw, represent in terms of depositional history (that is, the sequence and interrelation of events and processes embodied in the archaeologically observable site features). To this end, the paper re-specifies key contextual relationships at the three excavated sites and addresses the time-depth that each series of site contexts represents. It also considers what the spatial and artifactual relationships—both within and between the sites—may reveal about the ordering of settlement locally and regionally. There has been an understandable assumption that there must be more buried bronzes and elaborate artifacts, like those discovered beneath the Anozie family compounds between 1937 and 1964, to be found in the close vicinity and in the broader Igbo-Ukwu area. Although there will undoubtedly be much to discover, including early ceramics, this article concludes that the principal items recovered 50 years ago, and to a degree also their circumstances of deposition, may represent a unique situation and a key juncture in early Igbo history.

Resumé

Cet article pose un regard nouveau sur ce que représentent les différents contextes du site d’Igbo-Ukwu soigneusement examinés par Shaw, plus particulièrement l’histoire des dépôts archéologiques (c’est-à-dire la séquence et l’interrelation des événements et des processus, parties intégrantes des caractéristiques archéologiques observables du site). A cette fin, l’article réaffirme les principaux liens contextuels sur les trois sites fouillés et aborde la chronologie de chaque série de contextes dans les différents sites. On examine également ce que les relations spatiales et “artefactuelles” dans chaque site et entre les sites peuvent révéler sur l’agencement des foyers de peuplement, à la fois localement et au-delà. On a supposé, à juste titre, qu’il devait y avoir d’autres bronzes enfouis et d’autres artefacts élaborés, comme ceux découverts entre 1937 et 1964 sous les enclos de la famille Anozie, à trouver dans le proche voisinage et dans la région d’Igbo-Ukwu. Au moins en ce qui concerne les céramiques anciennes originales, il y aura sans doute encore beaucoup à découvrir. Cet article s’achève cependant sur l’idée que les principaux objets retrouvés il y a cinquante ans, et dans une certaine mesure aussi les circonstances de leur dépôt, peuvent représenter une situation unique et un moment clé de l’histoire ancienne des Igbo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Thurstan Shaw’s excavations in the northernmost part of Igbo-Ukwu town near Awka in eastern Nigeria, in 1959–1960 and 1964, involved the investigation of three distinct locations, one of which was 50 m to the southwest of the other two (Shaw, 1970). This spatial relationship is one among several basic observations that can help to elucidate the cultural and temporal relationship among the sites. There has been an understandable tendency, given the thousands of ancient artifacts recovered during the excavations, to regard them as coming from a single context.

As a result, the idea that there might be a considerable difference in the times of deposition for the various groups of items has not received the attention that it merits. This article contributes to a better understanding of the character and significance of the Igbo-Ukwu sites and their associated items by focusing primarily, though not exclusively, on the deposition of the excavated site features and materials. At its core, this article features an analysis of the site findings through the principles of contextual association. However, it also considers several other aspects of interrelationship (including the symbolic cross-referencing of artifact forms and motifs) and reviews what the new dating of organic samples from the site might add to future interpretations.

This contribution is based upon a re-analysis, carried out by present author from 1982 to 1987, of the excavation contexts encountered, investigated, and recorded at Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw and his field team up to 25 years earlier (see McIntosh, this issue). While working on West African archaeological materials during the period 1977–1982, including as a Research Assistant to Professor Shaw, I realized that close re-study of the Igbo-Ukwu sites and materials could be an instructive medium for exploring ideas that I was formulating about material culture and history more generally. Between 1982 and 1984, I had the opportunity not only to spend two years on the academic staff at the University of Nigeria at Nsukka, but also to work closely with Dr. Fred Anozie and to observe, albeit somewhat superficially under the circumstances, several aspects of the cultural life and history of the people of both the Nsukka area and the Awka-Anambra uplands.

Context and the Study of Symbolic Representation in Archaeology

To begin, it may be helpful to briefly summarize the approach to context and material culture interpretation that informed the doctoral research on which this contribution is based (Ray, 1987, 1988). This work took place during the early- to mid-1980s when there was a philosophical reaction in archaeology against regarding past cultures as systems whose underlying economic and symbolic structures were the objects of inquiry. Cultural phenomena were often fit within globalizing, normative, and functional schemes, and explained according to processes that inexorably led to greater cultural complexity through time, featuring universal underlying social evolutionary trends (O’Brien, 1996; Redman et al., 1978; Shennan, 2002). The reaction against this archaeological paradigm manifested (among other ways) in the interest in symbols and meanings expressed in and through objects, drawing most productively upon the work of the cultural philosopher Pierre Bourdieu (1977) and the social theorist Anthony Giddens (1979).

In my doctoral thesis, this theoretical grounding was complemented by ideas about the active deployment of objects allusively, and the workings of metaphor in both objects and ritual, developed from insights from the studies of anthropologists Victor Turner (1957, see also 1969, 1975), Clifford Geertz (1972, see also 1973), James Fernandez (1974, 1977), and from the hermeneutic and interpretive theory of Paul Ricoeur (1976). The approach to archaeological interpretation developed in my thesis was therefore grounded in a view of material culture as actively constituted through the fundamentally allusive character of social communication—especially through the workings of metaphor. Summarizing the view of Giddens that societies are comprised of people actively engaged in the negotiation of the terms of social engagement, I wrote: “Thus individuals are perceived fundamentally as strategising. They reproduce social relations through the active deployment of existing, habitual social practices and codes (‘rules’) and of material, ideological, and sociopolitical resources. The resources available include (the manipulative potential of) both time and space” (Ray, 1988, p. 16). And, after Bourdieu: “People are both discursively and practically conscious, rule-manipulative and again strategising. Strategies concern the alignment of ideology and interests in the negotiation of power, and tradition naturalises social inequality” (Ray, 1988, p. 17).

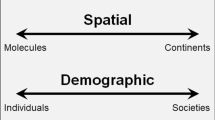

I explained how these ideas affect archaeological interpretation through reference to the often-deliberate ordering of deposits and residues and the active manipulation of artifact forms and decoration. The meaning and purpose behind this management of the material world can be recovered through an appreciation of the enactment of cultural and behavioral codes in specific archaeological contexts, using careful observation and analogy. The physical context of archaeological remains (e.g., where objects are located in the ground, why we see specific placements and associations) and the fundamentally allusive character of complex material forms together provide clues to understanding why certain symbols and forms have been created and deployed—often metaphorically—and thus what historical circumstances have led to observable archaeological dispositions.

Beyond their physical context, archaeological remains also have an historical context (the historic juncture or concatenation of circumstances that led to the artifact arrangement we observe). So, an understanding of the interrelation of site contexts and material cultural practices is vital to our historical understanding of the residues and artifacts we encounter, rather than incidental to them. Both theory and observation inform our judgment regarding past meanings and purposes: The task of interpretation is to sift out what is most germane (significant) to an understanding of past cultural practices and dynamics.

Reinforcing initial inquiries by Shaw and the colonial anthropologist M. D. W. Jeffreys (1934), the studies of Michael Onwuejeogwu (1981) elaborated on Igbo rituals associated with the investiture and subsequent death and burial of a titled leader referred to, at least in the early twentieth century, as a “sacred king.” An interesting aspect of the putative correlation between such a personage and the burial at Igbo Richard was the close specificity to how the chosen individual was seated and then ritually inhumed at coronation, while the placement of the corpse when he died was similarly fixed upon a stool and placed in a chamber lined with elaborately carved panels. As will be noted below, such specification extended to what items were to be included in the burial, and even how they were to be arranged. The fact that the testimony recorded by Jeffreys pre-dated the initial archaeological discovery of Igbo-Ukwu is important since the prescriptions to be followed were not fully observed in the most recent sacred king burials, while the “archaeological” items retrieved from the burial chamber did closely reflect what was supposed to be included.

But why study the Igbo-Ukwu phenomena in this light? The answer is that the material culture and history embodied in the remains are almost unimaginable in their expressive richness and sophistication. Moreover, these materials and site contexts had been retrieved through one of the most accomplished episodes of archaeological examination in an African setting up to that time, enabling their interpretation through reference to cultural histories and practices (Afigbo, 1982; Onweujeogwu, 1981). However, there had been insufficient attention to the interrelation of material cultural forms and representations and to the spatial arrangement of artifacts and residues, or indeed to any details in the early testimony recorded by Jeffreys.

Evolving Interpretations of Igbo-Ukwu by Thurstan Shaw

Fifty years on, it remains an incredible feat that Thurstan Shaw was able to secure multiple specialized analyses and carry out his own studies of the huge number of objects from the 1964–1969 excavations, while also working full-time to establish Archaeology as an independent academic discipline at the University of Ibadan (including recruiting new staff, setting up laboratories, and carrying out excavations at Iwo Eleru rockshelter). Shaw’s exemplary publication of this work has been widely noted, but what has received less notice was his publication of Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu (1977) by Oxford University Press in Nigeria. This book, written “for both the student of Nigeria’s history and the general reader,” included a first-person account of the complexities of the excavation itself, as well as a reflective narrative about “what it all meant”—the interpretations of the sites and the symbolic representations of individual objects and the wider significance of the discoveries.

In the time between these publications—and subsequently (Shaw, 1995)—there was considerable (and at times heated) debate about the Igbo-Ukwu discoveries, not least concerning the radiocarbon dates (see below; also McIntosh & Cartwright, this issue). This debate took place because the early radiocarbon dates (apparently ninth century) disrupted what had been settled views about the origins of complex West African “forest” political-cultural entities and the character of regional political organization more generally. Igbo society was supposed to have been “stateless” (cf. Horton, 1971) from time immemorial, while institutional complexity was held to be unique to highly ranked societies featuring craft and other specializations (including military), tribute and taxation, and so on.

This view of political and ritual authority in Anglophone West Africa had become embedded through the requirements of “efficient” colonial administration. Simply put, it was desirable for subject peoples to possess chiefship to more easily institute “indirect rule.” Where fixed hierarchical statuses did not exist, colonial regimes deemed it necessary to create them. This explains British colonial interest in Nri sacred kingship in the Awka-Agukwu area east of the Niger River southeast of Onitsha and why they sought to create “warrant chiefs” among the Igbo, where none had formerly existed (Afigbo, 1972).

When Thurstan Shaw published the full report on his 1959–1964 excavations, he sought to define an “Igbo-Ukwu Culture” following the archaeological interpretive traditions of the day. He began with the deceptively simple but crucial observation that “the Igbo-Ukwu sites must surely represent something exceptional rather than something typical and commonly repeated in the society that was responsible…(and in particular because) accumulated wealth is represented and, one would suppose, a considerable vesting of social and spiritual power and prestige” (Shaw, 1970, p. 268). While awaiting research on local history, Shaw was able to point to a tradition claiming that the northwestern area of Igbo-Ukwu town was once part of the adjacent town of Oreri, which, like nearby Agukwu (north-westwards again), possessed a sacred kingship system in living memory (cf. Anadi, 1967, cited in Shaw, 1970, p. 271). Shaw also noted some similarities of practice between the burial and adornment of the “chiefly” figure buried at the Igbo Richard site and the sacred kingship system described in a report by the colonial government administrator M. D. W. Jeffreys, which was later converted into a dissertation at the University of London (Jeffreys, 1934). By these means, Shaw identified correlations, but not necessarily continuities, in practice across the millennium separating these ethnographic observations from the archaeological remains of Igbo-Ukwu.

By 1977, M. A. Onwuejeogwu had completed his doctoral research on the Igbo kingdom of Nri (later published as a book in 1981). When Shaw wrote Unearthing Igbo Ukwu, he reported some of Onwuejeogwu’s interim findings, highlighting practices connected with the “Nri ritual system” that might explain aspects of the burial of an important titled man (see below) and the reasons why the “store-house of regalia” could be regarded as an obu, a kind of temple situated within a titled man’s compound (Shaw, 1977, p. 94–102). Among the most interesting of Onwuejeogwu’s findings, certainly from an archaeological standpoint, are the congruences between recent artifacts and their ancient counterparts. These included coiled snakes, distinctive facial scarifications (and the iron knives used to cut them), grasshoppers and beetles, title staffs, bronze bells, and so on. This led Shaw to conclude that “these objects belonged to a highly symbolic and ritualized culture comparable to (those) still existing in the present Awka and Onitsha provinces and parts of Nsukka, Udi, Okigwe and Orlu, but centred around two cores: the one core at Nri and the other at Oreri” (Shaw, 1977, p. 100).

In comparison to his interpretations of material symbolism or sociopolitical context, Shaw understandably felt himself to be on safer ground when tracing the sources of metal ores used in the recovered metalwork and estimating what he termed “the economic foundation” of the early Igbo-Ukwu cultural manifestations (1977, p. 103–107). Although he acknowledged Onwuejeogwu’s view that the great wealth accompanying the Igbo Richard burial was potentially most appropriate for a rich secular leader such as a high-ranking titled ozo man, Shaw remained content to see the Igbo-Ukwu finds as belonging ultimately to the system presided over by the “priest Kings of Nri” (Shaw, 1977, p. 94–102).

Igbo Richard: Stratigraphic and Associative Relationships

Igbo Richard was the western-most of the three sites selected by Shaw for excavation in 1959–1964. It had the most deeply buried remains, the deepest of which featured a richly adorned and accoutered corpse that was deduced to have been carefully arranged upright within a wood-lined burial chamber. As will be explained below, re-examination of the 1960 site records in 1986 identified contextual associations not previously thought to be significant, including the form and location of a distinctive stone bead.

The Igbo Richard burial complex was first encountered through the digging and lining of a narrow-shafted water cistern, when this means of capturing and storing rainfall for drinking water was still commonly practiced in the eastern Awka uplands. The realization that finds made while digging this cistern were archaeologically significant came when Shaw began to question whether items similar to those discovered in 1938 at Isaiah Anozie’s compound had been discovered elsewhere. In 1959, excavation revealed the presence of another cistern in the same area as the first. This comprised an access shaft (0.5 m wide) which extended to a depth of 5 m, at which point it expanded into a bulbous water storage chamber at least 2.5 m in diameter. It was deduced that this cistern had become in-filled gradually with at least two stages of refuse deposition. As the excavation season continued into 1960, another sounding (1 m wide, but narrowing to 0.5 m) was opened 5 m to the southwest of the cistern; this encountered the burial chamber and reached its former floor at a depth of nearly 8 m below the modern ground level. Besides these features, excavations at Igbo Richard found (at varying depths) two shaft-like water storage cisterns, two pits, and a discrete cluster of objects (Fig. 1). A group of human bones was also discovered directly above the burial chamber. These associated finds had seemingly served to mark the approximate position of the burial chamber, but their character as deposits merited re-assessment. It should be noted that the two outlines of the “shrine” shown in Fig. 1 are intermediate between the top and base of the deposit (which mostly contained whole or substantially intact decorated ancient pots). The pit base was found at 2.6 m depth, but the shape shown in this figure is the plan of the pit at 1.83 m depth.

Igbo Richard: The Focal Burial and its Resonances

All the key stratigraphic and spatial relationships between the excavated artifacts and structural traces at Igbo Richard were recorded carefully by Thurstan Shaw and his team in the early weeks of 1960. My re-assessment in 1986–1987 involved close study of both the published material and of copies of Shaw’s original finds register (Ray, 1988, p. 106–107). To begin with, the published aggregate feature plan for the burial chamber (Shaw, 1970, p. 68, fig. 14) was set on one side. Then the full range of excavated features and items was re-characterized, and the dispositions were re-assessed, re-measured, and segregated into three groups. The first of these groups included the structural elements and mortuary fittings (Fig. 2). The second included the “grave goods” which accompanied the burial, but were not items of dress or direct personal adornment (Fig. 3). The third group included dress items found alongside the recorded human bones (Fig. 4).

The elaboration of the burial chamber architecture and choreography of furnishings had long been appreciated, along with the richly adorned corpse seated upon a wooden stool that had been decorated by two rings of bronze studs at top and base. However, what became clear from my re-examination was that it was possible to reconstruct not only the process of decay and collapse of the corpse itself (outlined by Shaw [1970, p. 264–266] in terms of two alternative scenarios), but also the direction of collapse of the wooden boards of the chamber that had been held together by iron nails and staples. In practice, the first collapse (of the seated and accoutered corpse) and the second collapse (of the surrounding wooden chamber roof and walls) could have been either temporally coincidental or overlapping.

The deposition of items within the chamber indicated that a set of highly prescribed interment practices had been followed. As noted above, ethnohistoric data indicated that these represented an elaborate and carefully furnished entombment of a sacralized authority figure. While the symbolism of key artifacts had long been established (e.g., the power of the leopard in the bronze casting of a leopard-skull, title-taking ceremonies in a cast bronze fly-whisk handle), others had not been subject to the same level of scrutiny (e.g., the multiple representations of snakes’ heads on the copper “crown” [Ray, 1988, p. 255–256]).

The symbolism of artifacts within the chamber was clearly intricate, as were the arrangement of the artifacts. In my doctoral thesis, I explored the links between practices surrounding the sacred kingship system of Agukwu-Oreri, which had been documented circa 1910–1969, and the materials from the Igbo Richard burial chamber to resolve a controversy: was the deceased an eze nri (sacred king, of whom, historically, there had been relatively few) or a more secular holder of the ozo title (of whom there had always been many)? The fact that the individual was buried seated on a stool was not deemed sufficiently conclusive, given that ozo men had also been buried this way in some circumstances. The presence of a diadem (technically not a “crown”) ought perhaps to have been regarded as more indicative, but something more definitive was required (Ray, 1988, p. 97–105, 112–118, 124–131).

The nature of the “beaded cylinders” (beads strung on an openwork copper wire frame) as armlets was correlated with testimony recorded at Agukwu by Jeffreys (1934, p. 31–33): “While alive he (the sacred king, Eze Nri) will wear a few Aka beads from Idu on his arm but when he is buried the Adama (cult priests) demand enough to cover his arm.” As described above, both Jeffreys and the ethnohistorian/anthropologist M. A. Onwuejeogwu (1981) had noted that the coronation ritual for an Eze Nri (involving symbolic inhumation and resurrection) precisely prefigured his eventual burial. During the investiture ceremonies, a diadem with eight eagle feathers was placed upon his head, and the apertures in the Igbo Richard copper circlet are best explained as having been created to facilitate the insertion of feathers. There are also, perhaps not coincidentally, eight such apertures (Ray, 1988, p. 130).

Equally significant is the prescription that two copper anklets were to be placed around the dead king’s ankles and “a carnelian bead, aka, was tied on his right wrist” (Onwuejeogwu, 1981, p. 87). Was there such a bead present in the Igbo Richard chamber? There is no reference to one in Onwuejeogwu’s comparisons between the excavated artifacts and historically attested practices (1981, p. 163–165), and Shaw made no mention of any such individual bead as being significant. I reasoned that, to be distinctive as a particular item, this bead would need to be large. And in fact, while several large carnelian beads were recovered from the Igbo Richard burial chamber, the largest of them had been distinctive enough to be given its own finds number during excavations (IR 355; Shaw, 1970, plate VIII, f). In addition to its pronounced facets, the distinctiveness of this bead was due to its perforation for suspension, which was bored to one side (rather than axial) so that it could be attached as a separate item (rather than strung in a necklace, for example). I then consulted Shaw’s finds register to locate it precisely within the chamber: If his (and my own) reconstruction of the chamber’s arrangement is correct, with the corpse placed on its stool facing southwards, then the bead, located at lower right within the primary burial deposit could very plausibly have been attached to the right wrist (Fig. 4; see also Ray, 1988, p. 130–131, Fig. 3.3).

Igbo Richard: Commemorative Deposits and Shrines

The form of the Igbo Richard chamber is difficult to reconstruct precisely, but the combination of iron staples and nails, and the observation of flat boards or panels indicates that there was likely a substantial box-like superstructure. The rings of bosses presumed to form the top and bottom of a wooden stool, the Y-shaped copper brackets, and the scattered items arranged where they fell from the corpse also indicates that the body would likely have sat upright in a wooden chamber. This structure, replicating the seating of the sacred king in his audience-chamber would have been regarded as a “shrine” suitable for making commemorative and propitiatory offerings when backfilled with earth (Ray, 1988, p. 237–241).

At some point after the burial chamber had been sealed, at least three distinct deposits were made close to or directly over its location (Fig. 1). The first, which had been placed directly over the chamber, was encountered at a depth of 1.5–2.0 m (approximately halfway between the top of the chamber deposit and the modern ground-surface). This deposit comprised human bones from at least five individuals, accompanied by shapeless groups of beads and two copper wristlets—one of which had bones inside indicating interment with its sometime wearer (cf. Shaw, 1977, p. 48). Three meters to the north was a narrow, shaft-like pit with uneven sides (unlike a cistern) that had been dug to a depth of 1.83 m; its backfill included finely decorated pottery sherds. The second deposit, at a significantly higher level, was an accumulation of items thought to be a series of pots and other material (again including beads) heaped upon one another. This was denoted a “shrine” based on analogy with other such piles of offerings attested in historically recent shrines. Finally, the third deposit, at the same shallow depth as the second, was a group of three metal-and-wood rod-shaped artifacts that had been placed on another former ground surface together with a sticky clay-like substance (Shaw, 1970, p. 64–67).

It was clear, therefore, that while there had been superposition of some of the Igbo Richard remains (Fig. 1), there was also some spatial segregation. Accordingly, I attempted in the 1987 analysis to correlate activities (temporally) between the different contexts by trying to identify trends in the rate of the localized deposition of miniature (presumed votive) objects—deliberately ground-down pieces of potsherd that Shaw had termed “pottery pegs.” As shown in Fig. 5, three areas were chosen for a peg count of recorded densities at different levels to sample different parts of the site where the pegs were recorded as having high concentration (Ray, 1988, p. 266–268). These areas were as follows: (1) Shaw’s excavation zone “Area XA” situated in the southeast corner directly over the burial area; (2) the discrete clustering of finds within the backfilled shaft denoting the “ancient cistern”; and (3) the closely recorded sequence from the balk initially retained between Areas XIA and XIIA towards the northeastern quarter of the Igbo Richard excavation area (Shaw, 1970, Fig. 11).

The “shrine” appears to have involved a rapid accumulation at a relatively high level in the excavation area. The peg counts associated with this feature were high (1500–2000 items), supporting its interpretation as a shrine in receipt of the most votive offerings, but there was no meaningful correlation to be observed with depth. The pegs from the area of the “shrine” itself (Fig. 1) were not included because this was a single discrete deposit and was relatively high (late) in the site sequence (Shaw, 1970, Fig. 19). It was therefore deduced that the pegs in its vicinity did not accumulate over an extended period. The depth-related incidence of pegs does not directly correlate with the processes of accumulation and infilling, which varied from context to context (see below).

The three selected contexts are somewhat varied in terms of their genesis and stratigraphic character, so the timing, duration, and periodicity of activity likely differed between them. For example, the cistern was likely dug in one episode and used over a relatively brief period before being infilled gradually by dumping refuse into it. Accordingly, the discovery of pegs within “Spit 20,” where the ancient cistern was observed, does not indicate contemporaneity based on the pegs in the area above the burial chamber, because the depositional history of each location, including the rates and nature of soil deposition, would have been different.

Although the dates for each context are by no means certain, Shaw denoted the deepest-cut feature the “ancient cistern” because it had no items similar to more recent artifact forms. Meanwhile, the area above the burial chamber would have been infilled twice: first rapidly, after the chamber was closed, and then by stages as the chamber decayed and collapsed. We would expect that areas away from these infilled features would have a more limited vertical distribution of items. This is, in fact, what we find, with the pegs in the balk only observed in the upper 12 excavated spits, but with two “peaks” in deposition (Fig. 5). However, the vertical distribution of pegs in the other two areas give us some indication that there were periods of faster and slower deposition of these presumed offertory items everywhere in the vicinity of the burial chamber. For example, frequencies of 20 or more pegs were recorded at three different levels directly above the burial area, and two of these corresponded directly with the human bones, copper bracelets, and beads found at roughly this same level.

The greatest quantities of pegs in the ancient cistern were recorded at a level that presumably represented the most rapid rate of deposition (across a relatively brief time-period) from soon after the infilling began through to when that process was complete. In contrast, the distribution of pegs across the burial area indicates a prolonged period of deposition, perhaps suggesting that there had been some long-term active awareness of the presence of the past burial of a significant authority figure here. Of some interest is the correlation between a “late” peak over the burial area, in the “balk” location east of the “shrine” deposit, and in the level at which the “shrine” deposit was found. One is left to wonder whether this could mark a historically distinct and late (but still nonetheless chronologically “ancient”) revival of interest in the oral tradition concerning the Igbo Richard burial.

Some of the “peaks” in the area over the burial could represent periodic episodes when the “shrine” attracted more attention and use. At the same time, the digging and infilling of the cistern could have been carried out at a time when, maybe coincidentally, there was a lot of “shrine-related” activity nearby, resulting in considerable quantities of pegs having been deposited within a relatively short period. What is evident is that during the (likely relatively short) period of infilling the cistern, there was a sustained high level of ritual activity associated with probable shrine offerings, or perhaps alternatively, a period of shrine destruction and the tipping of “damaged” shrine material into the cistern when it was being used as a disposal pit.

The foregoing concludes that there were probably two periods of high-intensity ritual deposition at the Igbo Richard site following the closure of the burial chamber. The first probably coincided with the upper interment of human bones. The second was apparently marked by the deposition of the pots in the “shrine,” the infilling of the ancient cistern, and the placement of the rods—all three potentially having constituted a commemorative “re-sacralization” of the spot. Given the similar ornate character of the Igbo Richard pots from the “shrine” and the pit, as well as the pottery found in the principal deposit at Igbo Isaiah, it is reasonable to propose that the timing of this activity may have been broadly synchronous with the final use and abandonment of the structure within which the wealth of items from the Igbo Isaiah site had been placed.

Igbo Isaiah: The Concentration and Disposition of Material Items

During my research reappraisals in 1987–1988, I questioned assumptions about the significance of the layout within the much shallower burial of artifacts in the rich and complex assemblage situated 50 m away at Igbo Isaiah, particularly in reference to the structure within which they had been placed. Caroline Sassoon’s excellent reconstruction painting manifest Shaw’s interpretation of the deposit as a “store-house of regalia” placed upon a dais that would have measured approximately 3 m × 1.5 m at one end of a lineage shrine of indeterminate length. From sword scabbards and calabash-fittings, to strings of beads and miniature crotal bells, Shaw was able to piece together all the various and often composite items that were (or had been) present (Fig. 6).

There can be no question that the various kinds of artifact found in the main grouping of items had been placed together on a flat surface, which one can reasonably assume was somewhat raised above ground level. It would in this way correspond to “altars” belonging to maximal lineage leaders that in some sense preserved the history of their lineages (Onwuejeogwu, 1981, p. 112–119). The fact that several of the items had been wrapped in cloth indicates that they were stored in the lineage-house and were only occasionally brought out to participate in key ceremonies.

One aspect not previously discussed in detail was the likely size and orientation of the structure within which the objects had been placed. Of particular significance to the redefinition effected in my study, the southwestern corner of the structure once surrounding the deposit was defined in reference to two post-holes (Shaw’s “Ph 5 and 6”) located some 4 m south of the concentration of objects. There is thus reason to suppose that the deposit may once have extended further southwards, and that the overall structure could have been up to 10 m long. Furthermore, the orientation of the reconstruction differed slightly from the description given in Shaw’s reports. The excavation area (Fig. 5, dotted outline) was clearly configured to facilitate a working area centered on the rich artifact deposit, insofar as it survived the digging that had unearthed the first objects found in the 1930s. This places the “store-house” on a decidedly northwest to southeast orientation.

Igbo Jonah: Questions of Pit Burial and Empty Space

The vast majority of the considerable area (ca. 140 m2) excavated at Igbo Jonah was found to be devoid of ancient features. Four pits were intercepted at the edges of the excavated area, and only two of the other five pits were more than 1 m in diameter. The deeply dug Pit IV has understandably been the focus of interpretive attention at Igbo Jonah, with less attention paid to the dispersal of features (mostly pits) and the site’s potential significance for the spatial organization of early settlement. Excavations covering 225 m2 across the three Igbo-Ukwu sites led to the full excavation of eight pits and the interception of four others. Apparently, all these pits had been deliberately and rapidly backfilled with differing degrees of orderly deposition, so they likely indicate the absence of occupied structures. This situation is significant because it correlates with an absence of observed post-holes and, in conjunction with the existence of several pits, suggests that the sites were once open space within a domestic compound. This enables (with some caveats) a tentative reconstruction of the spatial and functional relationships among the three sites.

The Reintegration of Activities at Igbo-Ukwu

Practices of Burial and Spatial Ordering

The disposition of archaeological remains within and between the three Igbo-Ukwu sites is potentially more informative than has previously been appreciated. For example, the eastward-pointing orientation of the two principal locations, where masses of artifacts were excavated, may be significant. Beyond the Igbo Isaiah “storehouse” to the east, it seems likely that there were no standing structures, and that this was an open space in antiquity. The “storehouse” itself likely faced outwards to the east, quite possibly with an area of restricted access behind it, such as an area of protected forest (“grove”) in which the Igbo Richard burial was located, its presence being commemorated by a lengthy series of offering deposits and possibly by individual shrines (Fig. 7). This suggested placement of the burial chamber and associated shrine deposits in a “grove” is informed by the historically attested setting of the Agukwu Nri “royal” obu with a thickly wooded area behind it, and the tradition that the sacred king was buried at Oreri “in a piece of bush set aside for the purpose” (Jeffreys, 1934, cited in Shaw, 1977, p. 98).

The Igbo Isaiah deposit represented an orderly laying out of objects, with groups of functionally similar or related items placed together. The idea that they had been abandoned rapidly during an episode of warfare is not credible since they would surely have been looted or otherwise removed in such a circumstance. It is reasonable to suppose that they were regarded as protected by unseen forces and therefore dangerous to approach or touch, leading them to be avoided and gradually absorbed back into the surrounding forest. There were no indications of later commemorative deposits having been placed in association with them; there was effectively a process of forgetting their former presence and significance.

The contrast between the sites of Igbo Isaiah and Igbo Richard is therefore not limited to depth of burial. The Igbo Richard burial was commemorated, at least for a reasonable length of time. In contrast, the Igbo Isaiah “storehouse” had been abandoned, and potentially more readily forgotten. As recounted to Thurstan Shaw at the time of excavations (1977, p. 94), the oral tradition of warfare having broken out between the people of Oreri and Igbo-Ukwu towns, with the consequent sequestration of the southeastern part of the former and its absorption to become the northwestern part of the latter is an entirely plausible explanation, but of course this hypothesis requires further evidence.

Chronology and Sequence

The three Igbo-Ukwu excavation sites clearly encapsulate complex processes and timescales whose correlation represents a significant interpretive challenge. Although their spatial relation throws light on cultural and functional relationships over an extended period, and some contemporaneity cannot be doubted, the period encompassed by the sites deserves closer attention. To establish a clear sequence in their depositional histories, both across the stratigraphic sequence at Igbo Richard and between the three sites, it was obvious from the outset that chronometric dating of appropriate samples would be necessary.

As Susan McIntosh (this issue) notes, there is a considerable contrast between when Shaw took his samples for dating in the early 1960s and contemporary practice in the 2020s. Not only do we have the advances of accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS), but the samples for radiocarbon dating can be smaller and drawn from a wider range of organic materials. Equally important are the requirements to sample short-lived materials (for instance, sapwood and twigs, rather than heartwood from trees) and to date adequate numbers of samples for modeling statistically significant trends. The interrelation of contextual and chronometric data from sites enables us to gain yet greater precision concerning the duration of episodes of activity.

What this means in practice is that the dates obtained on wood from Igbo Richard can no longer be regarded as unproblematic, nor can dates obtained from carbon or charcoal drawn simply from “bulk” (e.g., sieved, dispersed) samples. This is why the dates obtained recently by McIntosh and Cartwright (this issue) are so important, despite the sampled fabric having been attached to a bronze object found by casual digging in 1938, rather than from among the items recovered during Shaw’s carefully controlled excavations. As noted by the authors, this establishes a date for the “final wrapping” of the item, and by extension the wrapping of other items in the deposit, sometime between the mid-eleventh and late twelfth century CE.

This possibly provides a broadly coincident date-bracket for at least the terminal phase of all three Igbo-Ukwu sites. If the “final wrapping” of the Igbo Isaiah items represents a “terminal phase” at that site (close to its final demise as an active “depository” or “lineage shrine”), the question therefore becomes what would constitute “terminal activity” at Igbo Richard and Igbo Jonah? Based on the interment of at least the “pottery pile” shrine at Igbo Richard and the digging of Pit IV at Igbo Jonah, one answer would have to be that there was in effect a commemoration, but also a ritual “shutting down” (or ritual seclusion) of the formerly venerated site. As outlined by Onwuejeogwu (1981, p. 57–61), this could have represented the onset or advent of a prolonged period of extensive disruption including the rise of the Aro trading and warfare network and ultimately the impact of the rise of Benin and the Atlantic slave trade.

Igbo-Ukwu Reintegrated: Historical Juncture and the Igbo Past

The close re-study of the Igbo-Ukwu artifacts that I undertook over 30 years ago pointed out, even more categorically than Shaw, that the patterns of artifactual and contextual association were intricate and above all dense. By that latter term, I mean that figurative and symbolic allusions were piled upon one another with notable frequency. If there were material “statements” concerning symbolism, the role of institutions, the qualities of leadership, and above all a historical narrative, then they were made with great precision and multiple reference. It was as if there were key points of symbolism and meaning that the artifacts were not only designed to convey, but also in a real sense to define. This is what I meant when I identified the workings of “historical metaphor” at ancient Igbo-Ukwu (Ray, 1987, 1988, 2000).

The period of the original manufacture of the Igbo-Ukwu items therefore can be seen as a “cultural horizon,” and I have argued that this articulated with oral histories about the development of ritualized kingship in this part of Igboland. Put another way, the manufacture of these items, coincident with the inhumation of the “ritual authority figure,” took place at a time when the Igbo past became deliberately historicized. The items concerned were not simply “regalia”—they were deliberately created to make manifest a particular version of the history of a “coming-into-being” of key beliefs, practices, and ritual-political relationships. This circumstance makes it likely that the creation of this rich body of material was a one-off, and therefore unlikely to have been repeated. It represented a concatenation of unique historical circumstance and process.

However long the complex regalia and treasures of Igbo-Ukwu were in use, it seems likely that the production of fine and elaborate allusive ceramics and intricate lost-wax castings came to an end so long ago that their presence in the soil was forgotten. While there were evident continuities in both ritual practice and in manufacture (for example, in iron smithing, but not smelting), the historical juncture that had led to the production of the fine bronzes was long past by the advent of the colonial era over 100 years ago.

In trying to establish the historical context of ancient Igbo-Ukwu, archaeologists have largely looked for relationships with other institutions of kingship and emerging states in geographically proximate areas, such as Ile-Ife and the other Yoruba kingdoms, Benin, and Igala. There are undoubtedly cultural and historical parallels and continuities—elephant tusks, depictions of leopards, the use of fly-whisks and crowns/diadems to denote power—but what emerged in those other Yoruba, Benin, and Igala kingdoms was a parallel sacred and secular centralization of authority, ultimately backed up by both the threat and the exercise of military might.

Retrospect and Prospect: The Futurity of Igbo-Ukwu Archaeology

There has been, and continues to be, an assumption that more sites with a material culture similar to Igbo Richard, Igbo Isaiah, and Igbo Jonah will eventually be encountered in the environs of Igbo-Ukwu or further afield. It is almost certainly the case, as we heard during the “Igbo-Ukwu at 50” symposium, that more pottery corresponding to the zenith of Igbo-Ukwu will be found as more archaeological work is undertaken in the region. And discoveries of artifacts such as distinctive broad-grooved fine pottery will no doubt be made even further afield, as has been demonstrated in the Nsukka area (Ray, 1984, 1988, p. 226–228). Nevertheless, it may be that there will be no further discoveries of elaborate bronze-work together with beads and finely wrought copper items. If that is the case, then what would we make of the Igbo-Ukwu material in the context of the development of what many have called “social complexity” in the forest regions of West Africa?

A pervasive idea in the late twentieth century was that the most important interpretive task for historians and archaeologists was to chart the “evolution to complexity” (e.g., Earle, 1997). In this framing narrative of world history, Igbo society, past and present, was long held to be a “stateless” or “acephalous” society without leaders (cf. Fortes & Evans-Pritchard, 1940; Horton, 1971; Northrup, 1978). In recent years, however, the notion that the complexity of societies in sub-Saharan Africa was somehow less significant in the apparent absence of ascribed statuses and fixed social stratification has been questioned, and sometimes with explicit reference to Igbo history (Henderson, 1972; McIntosh, 1999a, 1999b; Oriji, 2011; Stahl, 1999). There have also been influences from neighboring, militarily venturous, polities, leading to the adoption of kingly paraphernalia, for example, in areas close to the Igala kingdom in the Nsukka Igbo and other northern territories (Cole & Aniakor, 1984; Oguagha & Okpoko, 1985). Nowhere, however, has this been more evident than in the areas west of the Niger River and Onitsha, where the institution of obi-ship developed in response to the proximity of the Empire of Benin (Ejiofor, 1982).

In terms of the fixity of hierarchy and institutions, historical Igbo societies certainly never witnessed the development of states with inter-generational, ascribed, social stratification, and the apparatus of a centralized bureaucracy, standing armies, and so forth. However, it has long been understood that the political economies of Igbo societies were based upon sometimes hotly contested status rivalries and achieved statuses that often resonated from generation to generation in leading families (e.g., Falola, 2005; Ifemesia, 1979; Isichei, 1976). The Igbo people nonetheless were—and remain—diligent farmers, expert craftspeople, and highly successful traders. Historically, the establishment of conditions conducive to trade was always of paramount importance. The Igbo-Ukwu remains indicate that not only were there many past “pathways” to social complexity, but that ritual authority and raw political dominance (cf. Asombang, 1999) could also provide a path to the creation (and in some cases, burial) of astonishingly rich and accomplished artifacts, as Susan McIntosh (1999a, 1999b) pointed out some while ago (see also, Ray, 1987, 1988).

References

Afigbo, A. E. (1972). The warrant chiefs: Indirect rule in southeastern Nigeria, 1891–1929. Longman.

Afigbo, A. E. (1982). Ropes of sand (studies in Igbo history and culture). University Press Ltd.

Anadi, I. C. K. (1967). Our history and cultural heritage. Etudo Ltd.

Asombang, R. (1999). Sacred centers and urbanisation in West-Central Africa. In S. K. McIntosh (Ed.), Beyond chiefdoms: Pathways to complexity in Africa (pp. 80–87). Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline for a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

Cole, H. M., & Aniakor, C. G. (1984). Igbo arts: Community and cosmos. UCLA Museum of Cultural History.

Earle, T. (1997). How chiefs come to power: The political economy in prehistory. Stanford University Press.

Ejiofor, L. U. (1982). Igbo kingdoms: Power and control. Africana Publishers Ltd.

Fernandez, J. (1974). The mission of metaphor in expressive culture. Current Anthropology, 15(2), 119–145.

Fernandez, J. (1977). The performance of ritual metaphors. In D. Sapir & J. C. Crocker (Eds.), The social use of metaphor (pp. 100–131). University of Pennsylvania Press.

Falola, T. (Ed.). (2005). Igbo history and society: The essays of Adiele Afigbo. Africa World Press.

Fortes, M., & Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1940). Introduction. In M. Fortes & E. E. Evans-Pritchard (Eds.), African political systems (pp. 1–25). Oxford University Press.

Geertz, C. (1972). Deep play: Notes on the Balinese cockfight. Daedalus, 101, 1–38.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books.

Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems in social theory. Macmillan.

Henderson, R. N. (1972). The king in every man: Evolutionary trends in Onitsha Ibo society and culture. Yale University Press.

Horton, R. (1971). Stateless societies in the history of West Africa. In J. F. A. Ajayi & M. Crowder (Eds.), the history of West Africa (Vol. 1, pp. 78–119). Longman.

Ifemesia, C. (1979). Traditional humane living among the Igbo: An historical perspective. Fourth Dimension Publishers.

Isichei, C. (1976). A history of the Igbo people. Macmillan.

Jeffreys, M. D. W. (1934). The divine Umu Ndri: Kings of Igboland. University of Cambridge.

McIntosh, S. K. (1999a). Pathways to complexity: An African perspective. In S. K. McIntosh (Ed.), Beyond chiefdoms: Pathways to complexity in Africa (pp. 1–30). Cambridge University Press.

McIntosh, S. K. (Ed.). (1999). Beyond chiefdoms: Pathways to complexity in Africa. Cambridge University Press.

Northrup, D. (1978). Trade without rulers: Pre-colonial economic development in south-eastern Nigeria. Clarendon Press.

O’Brien, M. J. (1996). Evolutionary archaeology: Theory and application. University of Utah Press.

Oguagha, P., & Okpoko, I. (1985). History and ethnoarchaeology in Eastern Nigeria: A study of Igbo-Igala relations. Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 11 Archaeopress.

Onwuejeogwu, M. A. (1981). An Igbo civilisation: Nri kingdom and hegemony. Ethiope Publishing Corporation.

Oriji, J. N. (2011). Political organisation in Nigeria since the Late Stone Age: A history of the Igbo People. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ray, K. (1984). Field research bulletin on excavations at Lejja. Mimeo report, Department of Archaeology, University of Nigeria.

Ray, K. (1987). Material metaphor, social interaction and historical reconstruction: Exploring patterns of association and symbolism in the Igbo-Ukwu corpus. In I. Hodder (Ed.), The archaeology of contextual meanings (pp. 66–77). Cambridge University Press.

Ray, K. (1988). Context, meaning and metaphor in an historical archaeology: Igbo Ukwu, eastern Nigeria. University of Cambridge.

Ray, K. (2000). Material metaphor, social interaction and historical reconstruction: Exploring patterns of association and symbolism in the Igbo-Ukwu corpus. In J. Thomas (Ed.), Interpretive archaeology: A reader (pp. 398–417). Leicester University Press.

Redman, C. L., Langhorne, W. T., Berman, M. J., Versaggi, N. M., Curtin, E. V., & Wanser, J. C. (Eds.). (1978). Social archaeology: Beyond subsistence and dating. Academic Press.

Ricoeur, P. (1976). Interpretation theory: Discourse and the surplus of meaning. Texas A&M University Press.

Shaw, C. T. (1970). Igbo–Ukwu: An account of archaeological discoveries in Eastern Nigeria (Vols. 1-2). Faber and Faber Limited.

Shaw, C. T. (1977). Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu: Archaeological discoveries in eastern Nigeria. Oxford University Press.

Shaw, C. T. (1995). Those Igbo-Ukwu dates again. Nyame Akuma, 44, 43.

Shennan, S. (2002). Genes, memes and human history: Darwinian archaeology and cultural evolution. Thames and Hudson.

Stahl, A. B. (1999). Perceiving variability in time and space: The evolutionary mapping of African societies. In S. K. McIntosh (Ed.), Beyond chiefdoms: Pathways to complexity in Africa (pp. 39–55). Cambridge University Press.

Turner, V. W. (1957). Schism and continuity in an African Society. Manchester University Press.

Turner, V. W. (1969). The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. Transaction Publishers.

Turner, V. W. (1975). Dramas, fields and metaphors: Symbolic action in human society. Cornell University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ray, K. A Contextual Reintegration of Shaw’s 1959–1964 Igbo-Ukwu Excavation Sites and Their Material Culture. Afr Archaeol Rev 39, 387–404 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-022-09505-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-022-09505-6