Abstract

This systematic review aimed to provide an overview of reablement interventions according to the recently published ReAble definition and their effect on Activities of Daily Living (ADL). In addition, the most common and promising features of these reablement interventions were identified. Four electronic bibliographic databases were searched. Articles were included when published between 2002 and 2020, which described a Randomised or Clinical Controlled Trial of a reablement intervention matching the criteria of the ReAble definition, and had ADL functioning as an outcome. Snowball sampling and expert completion were used to detect additional publications. Two researchers screened and extracted the identified articles and assessed methodological quality; discrepancies were resolved by discussion and arbitration by a third researcher. Twenty relevant studies from eight countries were included. Ten of these studies were effective in improving ADL functioning. Identifying promising features was challenging as an equal amount of effective and non-effective interventions were included, content descriptions were often lacking, and study quality was moderate to low. However, there are indications that the use of more diverse interdisciplinary teams, a standardised assessment and goal-setting method and four or more intervention components (i.e. ADL-training, physical and/or functional exercise, education, management of functional disorders) can improve daily functioning. No conclusions could be drawn concerning the effectiveness on ADL functioning. The common elements identified can provide guidance when developing reablement programmes. Intervention protocols and process evaluations should be published more often using reporting guidelines. Collecting additional data from reablement experts could help to unpack the black box of reablement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With increasing age, older adults often experience functional disability, which is described as difficulty or dependency in the execution of daily functioning or Activities of Daily Living (ADL) (Covinsky et al. 1997; Fried et al. 2004; Lafortune 2007). ADL can be divided into basic self-care skills such as eating, bathing or dressing (bADL); more complex and instrumental activities such as using a telephone, doing the laundry or managing medications (iADL); and advanced culture and gender-specific activities not necessary for independent living such as hobbies, religion and working (aADL) (Reuben and Solomon 1989). Difficulties in executing ADL are associated with poor quality of life, depression, hospitalisation and nursing home placement, and increased disability (Arnau et al. 2016). It is therefore important to optimise older adults' active involvement and participation in daily functioning (Aspinal et al. 2016).

Older adults can generally rely on help from health and social care staff in performing everyday activities. However, these professionals often work in a task-oriented fashion; they are used to doing tasks for or to the individual, rather than doing tasks with them in a more rehabilitative and person-centred manner (Aspinal et al. 2016; Kitson et al. 2014). This task-oriented approach can lead to a downward spiral, with a greater loss of functions and paradoxically greater care consumption (Gingerich 2016; Schuurmans et al. 2020; Whitehead et al. 2015). Therefore, a paradigm shift in health, respectively, social care is needed, which focuses on person-centeredness and promotes older adults' active involvement and participation.

An innovative approach that can guide this shift is reablement. As there was ambiguity on the concept of reablement, a Delphi study was conducted among 81 international experts that saw reablement defined as: “A person-centred, holistic approach that aims to enhance an individual’s physical and/or other functioning, to increase or maintain their independence in meaningful activities of daily living at their place of residence and to reduce their need for long-term services. Reablement consists of multiple visits and is delivered by a trained and coordinated interdisciplinary team. The approach includes an initial comprehensive assessment followed by regular reassessments and the development of goal-oriented support plans. Reablement supports an individual to achieve their goals, if applicable, through participation in daily activities, home modifications, and assistive devices as well as involvement of their social network. Reablement is an inclusive approach irrespective of age, capacity, diagnosis or setting” (Metzelthin et al. 2020).

Due to the use of different definitions of reablement before the existence of the ReAble definition, divergent results were found regarding the effectiveness. Reablement has shown positive effects on improving or maintaining ADL and physical functioning, quality of life, and reducing the risk of death or permanent residential care and healthcare costs (Ryburn et al. 2009; Sims-Gould et al. 2017; Tessier et al. 2016; Whitehead et al. 2015), while other reablement reviews have demonstrated no effects, reported a lack of intervention descriptions or could not include studies (Cochrane et al. 2016; Legg et al. 2016; Mjøsund et al. 2020). The contradictory evidence seems to link back to the conceptualisation of reablement. First, existing systematic reviews defined reablement differently, which led to different inclusion criteria and requirements. Consequently, different conclusions were drawn on the effects of reablement. As a result, one systematic review found no indication that reablement led to less dependency in ADL functioning (Cochrane et al. 2016). In contrast, four systematic reviews found that reablement showed positive results in optimising ADL functioning (Resnick et al. 2013; Sims-Gould et al. 2017; Tessier et al. 2016; Whitehead et al. 2015). Second, reablement is often used interchangeably with other interventions; for example, in the review of Sims-Gould et al. (2017), four different types of interventions were included, namely reactivation, restorative, rehabilitation, and reablement. Lastly, another shortcoming is that the studied interventions show great variation in how reablement and its components are applied and shaped in practice. This is highlighted by Doh et al. (2019), who point out the variation of reablement interventions between and even within different countries.

Currently, it is unknown what the evidence on reablement is when this definition is used as a starting point. Given the objective of reablement, increasing independence, it is particularly interesting to look at daily functioning. Therefore, using the ReAble definition as a starting point, this systematic review aims to provide a current overview of reablement interventions internationally, and their effect on clients’ daily functioning, combined with identifying common and possibly promising features. This systematic review is guided by the following three research questions: (1) What are the effects of reablement on daily functioning among individuals in need of care irrespective of age, capacity, diagnosis, or setting?; (2) What are the common features of reablement interventions according to the elements addressed in the ReAble definition (e.g. assessment, goal-setting tools, and staff training)?; and (3) What are the most promising reablement features?

Methods

A systematic review was conducted following the guidelines published by the Cochrane Collaboration and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and META-analyses (PRISMA) statement (Akl 2019; Moher et al. 2009). A review protocol was established a priori and registered with PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, ID CRD42020215245).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible when the described intervention was in line with the criteria of the ReAble definition (Metzelthin et al. 2020). Therefore, participants included were ≥ 18 years old, and in need of care, irrespective of capacity, diagnosis or setting. Studies were included when interventions aimed to enhance an individual’s physical and/or other types of functioning; increase or maintain independence in meaningful ADLs at the place of residence; or reduce the need for long-term services. The interventions had to be delivered by an interdisciplinary team, include an initial assessment followed by regular assessments and contained a goal-oriented support plan. Interventions were excluded when problem-oriented (e.g. malnutrition, pain, falls); focussed on assessment and/or care management only; not delivered at the place of permanent residence (e.g. group sessions or at a community centre); delivered by different disciplines, but did not include interdisciplinary collaboration and coordination; and when studies compared outpatient with inpatient care. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials (CCTs) were included if ADL functioning was used as an outcome measure in terms of basic ADL/instrumental ADL/advanced ADL, if reablement was compared to usual care, and when they were published in English or Dutch between 2002 and 2020. The year 2002 was chosen because the study by Tinetti et al. (2002) is the first known study to introduce the term reablement.

Search strategy

The following electronic bibliographic databases were searched in July 2020 and repeated in July 2021: PubMed, CINAHL (EBSCO), PsycInfo (EBSCO) and the Cochrane Library. An information specialist at Maastricht University verified the search string (see Appendix 1). It used terms relating to or describing the population, intervention, outcome and study design. The search strategy used Medical Subject Headings (MeSH); if MeSH were not available, appropriate keywords were used. The initial search was conducted in PubMed, and search terms were modified if necessary, to make them applicable in other databases. To check the adequacy of the search string, two well-known references (Lewin et al. 2013; Tuntland et al. 2015) were used as key references to check whether they were identified by the initial search. This method is known for optimising the search and assuring that all relevant studies will be identified (Booth 2008; Cooper et al. 2018). The initial search string did not filter on the ageing population, however, as a result, we found many articles on rehabilitation (that were diagnosis-specific), which did not meet the criteria of the definition. To enhance the specificity of the search results, the choice was made to filter on the ageing population as most studies on reablement have been aimed at this cohort. However, also studies that were not explicitly aimed at older adults were eligible for our systematic review. To guarantee that no relevant studies were missed we conducted snowball sampling by checking the references of the included papers and consulted experts in the field of reablement. The experts were specifically asked for studies that were conducted on younger people.

Study selection

All search results from the different databases were merged, after which duplicates were removed. To facilitate the screening of results, the web-based application Rayyan was used (Ouzzani et al. 2016). Two researchers (LB and SM) independently screened the studies on title and abstract. If the inclusion criteria were met, both assessed the full text for eligibility. LB and SM decided independently whether the inclusion criteria were met. Both screened 5% of the studies using the title and abstract first; when the consensus was < 80% overall, an additional 5% was screened, after which at least 80% consensus was reached. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and, where required, arbitration by a third researcher (SZ). An additional snowball sampling was used on studies included in the final sample (Wohlin 2014). Their reference lists were screened and studies were included according to the screening process described above. Reference lists of existing reviews on reablement (Cochrane et al. 2016; Legg et al. 2016; Resnick et al. 2013; Ryburn et al. 2009; Sims-Gould et al. 2017; Tessier et al. 2016; Whitehead et al. 2015) were checked to ensure that no key publications were missed. After these steps, SZ performed a final check of which studies to include. The authors of the included studies were contacted, as were 39 experts affiliated with the ReAble network (https://reable.auckland.ac.nz/reable-network), with a request to check whether any important studies had been missed. When additional studies were suggested, they were screened for inclusion according to the process described above.

Data extraction and analyses

All information was extracted using a data extraction template, as shown in Appendix 2, which was created in Microsoft Excel for the current study (Microsoft 2016). Study characteristics (i.e. design, aims, hypotheses and target group), common intervention components (i.e. team composition, duration, assessment, and goal setting) and outcome data concerning the effects on daily functioning were also extracted. Study protocols and additional related publications were also used.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed by LB and checked by SM using the Critical Appraisal Checklists provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (Tufanaru et al. 2020). The checklist included the following criteria that were assessed: adequate method of randomisation (if applicable), allocation concealment, the similarity of groups at baseline, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors, method of measurement, statistical analyses and appropriate use of trial design. Risk of bias was rated for selection-, performance-, attrition-, detection- and reporting bias. Each aspect of methodological quality, the risk of bias assessment and the overall risk of bias for the entire set of the included studies were reported in tabular and narrative forms for each study. When an answer on the checklist items was "yes", a score of 1 was given, when the answer was "unclear" or "no", a score of 0 was given. The impact of methodological quality of studies was assessed using a narrative synthesis.

Results

Study selection

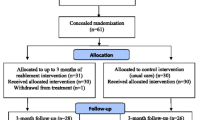

Searches of the electronic databases were carried out in July 2020 and yielded 7844 articles. A total of 1830 duplicates had been removed. The repeated search in July 2021 yielded an additional 876 unique articles. In total, 6,860 titles and abstracts were screened. Of these titles and abstracts, 104 studies were included for full-text screening. A total of fifteen articles describing fifteen independent intervention studies eventually met the eligibility criteria. An additional snowball sampling of the included studies and systematic reviews on reablement resulted in an extra thirteen studies. Finally, after consulting experts (from the ReAble network and the first authors of included studies), an additional eight studies were obtained. After the full-text screening of the snowball sample and studies suggested by experts, five were included in the final sample (n = 20). The flow chart of the screening process according to the PRISMA statement (Moher et al. 2009), including reasons for exclusion, can be found in Fig. 1.

Study and participant characteristics

The study and participant characteristics of the twenty included studies are shown in Table 1. Sixteen studies were RCTs and four were CCTs. The studies were conducted in eight countries. The twenty studies comprised a total of 6798 participants (range 61–1382), most were female 69.8% (range 21.6–87.5) and had a mean age of 79.5 ± 7.8 years old (range 34.5–87.7). Thirteen studies were conducted in community care and seven studies in institutionalised long-term care. Four studies used the diagnosis of dementia as their main focus group instead of a specific setting.

Outcomes and effects of reablement interventions on ADL functioning

Outcome measures, follow-up periods and outcome effects are shown in Table 2. ADL outcomes were measured with twelve different measures, of which ten were validated and/or standardised. Seventeen studies used validated and/or standardised outcome measures, while three studies used a self-developed non-standardised tool (Gitlin et al. 2006; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010). The most common measure, used in six studies, was the (unmodified) Barthel Index (Galik et al. 2014, 2015; Henskens et al. 2017; Powell et al. 2002; Resnick et al. 2011; Sackley et al. 2009). Six studies used a separate outcome measure concerning iADL (Gitlin et al. 2006, 2010; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Rooijackers et al. 2021; Szanton et al. 2019; Tinetti et al. 2002). In five studies, ADL was a secondary outcome measure (King et al. 2012; Lewin et al. 2013; Parsons et al. 2020, 2017; Rooijackers et al. 2021). In general, the total study duration varied from 4 to 48 months. Within these periods, the first follow-up varied from 10 weeks to 6 months, and the second to fourth follow-ups varied from 6 to 12 months.

With regards to the effects, ten studies described a significant improvement in ADL functioning in terms of bADL and/or iADL at the first follow-up (Galik et al. 2014; Gitlin et al. 2006, 2010; Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Powell et al. 2002; Szanton et al. 2019; Tinetti et al. 2002; Tuntland et al. 2015). At the second follow-up, six studies showed either a significant improvement in favour of the intervention group (Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Powell et al. 2002; Tuntland et al. 2015) or improvements were sustained from the first follow-up (Gitlin et al. 2006). The studies that also measured iADL demonstrated significant improvements at the first follow-up in all except one study (Szanton et al. 2019). One study showed that improvements were sustained at the first follow-up (Gitlin et al. 2006), and another study showed significant treatment effects in favour of the intervention group (Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010).

Intervention characteristics

To identify common features of the included interventions, the following results discuss the features that the interventions (n = 20) had most in common in terms of setting, duration, intensity, team composition, staff training, target group and the different intervention components. All interventions used a person-centred and holistic approach. These intervention characteristics and content, based on the criteria of the ReAble definition, are shown in Table 3.

Setting

In thirteen interventions, the setting was the participant's home (Gitlin et al. 2006, 2010; King et al. 2012; Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Parsons et al. 2020, 2017; Powell et al. 2002; Rooijackers et al. 2021; Szanton et al. 2019; Tinetti et al. 2002; Tuntland et al. 2015), while in seven interventions, the setting was a long-term care facility (Galik et al. 2014, 2015; Gronstedt et al. 2013; Henskens et al. 2017; Kerse et al. 2008; Resnick et al. 2011; Sackley et al. 2009).

Intervention duration and intensity

Thirteen interventions were time-limited and had a mean duration of 15.7 weeks (range 5–60) (Gitlin et al. 2006, 2010; Gronstedt et al. 2013; Henskens et al. 2017; Kerse et al. 2008; Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Parsons et al. 2020; Powell et al. 2002; Sackley et al. 2009; Szanton et al. 2019; Tuntland et al. 2015). In two studies, the intervention could also end earlier, when participants had achieved their set goals (Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010). Seven studies did not specify a maximum duration (Galik et al. 2014, 2015; King et al. 2012; Parsons et al. 2017; Resnick et al. 2011; Rooijackers et al. 2021; Tinetti et al. 2002), in addition, ten studies specified the intensity of the intervention, in terms of the amount and duration of sessions given (Gitlin et al. 2006, 2010; Gronstedt et al. 2013; Kerse et al. 2008; Langeland et al. 2019; Powell et al. 2002; Sackley et al. 2009; Szanton et al. 2019; Tinetti et al. 2002; Tuntland et al. 2015). Sessions varied from one session every four weeks to three sessions per week, with an average duration ranging from 0.1 to 6 h per week. On average, the effective interventions had a slightly shorter duration compared to non-effective interventions (mean 15.4 weeks, range 5–60 vs. mean 17.5 weeks, range 6–52). The intensity in terms of sessions and minutes spent per week could not be compared due to a lack of intervention details.

Interdisciplinary teams

Most interdisciplinary teams consisted of registered nurses (RN), nursing assistants (NA), occupational therapists (OT) and physical therapists (PT). In two studies, a medical specialist was also involved (Henskens et al. 2017; Parsons et al. 2017). On average, effective interventions had a more diverse team of health care professionals as a part of their interdisciplinary team than non-effective interventions (mean 3.5, range 2–6 vs. mean 3.2, range 2–7). In addition, results showed that OTs and PTs were a standard part of the team in seven of the effective interventions (Gitlin et al. 2006; Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Powell et al. 2002; Tinetti et al. 2002), in contrast to four of the non-effective interventions (Gronstedt et al. 2013; Kerse et al. 2008; King et al. 2012; Parsons et al. 2020; Sackley et al. 2009).

All studies described a coordinated collaboration between care professionals, only the method of collaboration and communication was not always specified. Four studies reported details on the frequency of these team meetings, which took place weekly (Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Parsons et al. 2020). Five effective interventions described that a member of the interdisciplinary team coordinated the intervention; this was often an RN, OT, or PT (Gitlin et al. 2006; Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Szanton et al. 2019), other effective interventions did not provide further details on the coordinator. Six of the non-effective interventions described that a registered nurse was appointed as the intervention coordinator (Kerse et al. 2008; King et al. 2012; Parsons et al. 2020, 2017; Resnick et al. 2011; Rooijackers et al. 2021), other non-effective interventions did not provide further details on the coordinator. The coordinators took the initial assessment and reassessment, set out goals with participants, monitored progress and coordinated team meetings and the education of staff.

Training of the interdisciplinary teams

In all but two studies (Parsons et al. 2020; Powell et al. 2002), staff training was described. Staff received specific training regarding care delivery (e.g. goal-setting tools, assessment procedures, etc.) in the form of lectures, seminars, courses, and education by other members of the team. This training varied in duration from one day to the form of weekly educational meetings over the intervention period varying from 5 to 60 weeks. Staff training could not be compared between effective and non-effective interventions due to a lack of detail regarding the contents of the training sessions given.

Target group

The thirteen studies conducted in community care described their target group in general as individuals in need of home care services or experiencing a functional decline. All interventions were aimed at individuals of ≥ 60 years old, except for three interventions that also included individuals of ≥ 18 years (Gitlin et al. 2010; Langeland et al. 2019; Tuntland et al. 2015), and one intervention including individuals between 16 and 65 years old (Powell et al. 2002). In terms of participant capacity, all interventions were aimed at individuals that required assistance with one or more ADLs, and/or experienced functional decline but were not completely care-dependent. One intervention was not only aimed at individuals with a diagnosis of dementia but also their caregivers (Gitlin et al. 2010); another was specifically aimed at individuals with Traumatic Brain Injury (Powell et al. 2002). The eighteen other interventions specifically excluded individuals in case of terminal illness, neurological disorder, and diagnosis of dementia because, according to the authors of these studies, these groups would benefit the least from the intervention or would eventually require institution-based rehabilitation or nursing home placement. Because only four non-effective interventions took place in community care (King et al. 2012; Parsons et al. 2020, 2017; Rooijackers et al. 2021), the target group cannot be compared with the target groups of the fifteen effective interventions that took place in community care.

The seven studies conducted in institutionalised long-term care described the target group as residents with a minimum expected stay of 3 months, and a minimum age of 55 years old. Three interventions were specifically aimed at individuals with a diagnosis of dementia (Galik et al. 2014, 2015; Henskens et al. 2017). Regarding the participants' capacity, all interventions were aimed at individuals needing assistance in their ADLs, and not meant for individuals in rehabilitation or cases of terminal care. As only one effective intervention that took place in institutionalised long-term care showed effects (Galik et al. 2014), the target group could not be compared with the target groups of the non-effective interventions.

Intervention components

Initial comprehensive assessment and regular reassessments

The assessment used in all interventions was generally interdisciplinary. A standardised instrument was used in ten interventions (King et al. 2012; Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Parsons et al. 2020, 2017; Powell et al. 2002; Szanton et al. 2019; Tinetti et al. 2002; Tuntland et al. 2015), for example, the interRAI Home Care Assessment (Landi et al. 2000). Six interventions used either a semi-structured interview method or a profession-specific intake assessment (Gitlin et al. 2006, 2010; Gronstedt et al. 2013; Henskens et al. 2017; Kerse et al. 2008; King et al. 2012) and four interventions did not use a standardised or protocoled assessment (Galik et al. 2014, 2015; Resnick et al. 2011; Rooijackers et al. 2021). Reassessments took place at intervals ranging from 10 to 52 weeks in seven interventions (King et al. 2012; Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Parsons et al. 2017; Szanton et al. 2019; Tuntland et al. 2015). The other interventions did not specify either if or when the reassessment took place. The results show that in seven effective interventions (Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Powell et al. 2002; Szanton et al. 2019; Tinetti et al. 2002; Tuntland et al. 2015), a standardised or protocoled assessment method was used, whereas this was the case in three of the non-effective interventions (King et al. 2012; Parsons et al. 2020, 2017).

Goal-oriented support plan

In sixteen interventions, the assessment method was also used to identify activities the participant perceived as meaningful and to develop a person-centred goal-oriented support plan (Gitlin et al. 2006, 2010; Gronstedt et al. 2013; Henskens et al. 2017; Kerse et al. 2008; King et al. 2012; Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Parsons et al. 2020, 2017; Powell et al. 2002; Sackley et al. 2009; Szanton et al. 2019; Tinetti et al. 2002; Tuntland et al. 2015). Four effective interventions and one non-effective intervention used validated and standardised goal-setting instruments (King et al. 2012; Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Tuntland et al. 2015), for example, the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (Law et al. 1990). In the other interventions, semi-structured interviews, the SMART method (Day and Tosey 2011), lists of important activities for the participant or input from other healthcare professionals and their families were used to set goals.

Interventions to reach clients’ goals

Five intervention components were identified. Effective interventions contained a broader offer of intervention components to reach clients’ goals than non-effective interventions (mean 4, range 2–5 vs. mean 2.8, range 2–4). ADL training, physical and/or functional exercise and education were the most common, and functional disorder management the least common components. Environmental adaptations were also an identified intervention component but did not recur as often as the other four. The specifications of these interventions are as follows.

First, ADL training was a recurring component in all effective and non-effective interventions. This entailed individual training in activities such as personal care and eating by encouraging clients to do (a part of) the activity themselves, followed by repeating and incorporating this training within the clients’ daily life. The participant also learned strategies to adapt an activity and make use of helping aids. OTs or RNs usually gave ADL training. No statements about effectiveness can be made because the same amount of effective and non-effective interventions included ADL training.

Second, physical and/or functional exercise was also a recurring component in all effective and non-effective interventions. Physical and/or functional exercises focused on physical activity in the training of strength, balance, endurance, and fine motor skills, but also on promoting active engagement in social and group activities. Training took place both individually as well as in group sessions. In most cases, it was not specified who provided the exercises, but if they did, it was often the PT who offered them. No statements about effectiveness can be made because the same amount of effective and non-effective interventions included physical and/or functional exercise.

Third, education played a role in reaching clients' goals in nine out of ten effective interventions (Galik et al. 2014; Gitlin et al. 2006, 2010; Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Szanton et al. 2019; Tinetti et al. 2002; Tuntland et al. 2015) and five non-effective interventions (Galik et al. 2015; Gronstedt et al. 2013; Henskens et al. 2017; Resnick et al. 2011; Rooijackers et al. 2021). Participants were educated on self-management, building confidence, healthy ageing, problem-solving, prevention strategies, stimulating (physical) activity and medication use. In addition to educating the participants, five effective interventions specifically described family and/or caregivers also receiving education to stimulate the participant in becoming less dependent on care (Galik et al. 2014; Gitlin et al. 2010; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Tinetti et al. 2002), this was also the case in one non-effective intervention (Galik et al. 2015). It was often not specified which member of the interdisciplinary team provided education.

Fourth, environmental adaptations played a role in six effective interventions (Gitlin et al. 2006, 2010; Langeland et al. 2019; Szanton et al. 2019; Tinetti et al. 2002; Tuntland et al. 2015) and four non-effective interventions (Galik et al. 2015; Gronstedt et al. 2013; Resnick et al. 2011; Sackley et al. 2009). Adaptations mentioned were the use of assistive technology (e.g. walking aids), home environment adaptations or repairs (e.g. safety rails), and providing medical equipment (e.g. blood pressure monitor). An OT often provided adaptations.

Last, the management of functional disorders, such as pain, continence, nutrition, skin integrity, testing of blood and urine, and management of medication, was incorporated in five effective interventions (Gitlin et al. 2010; Lewin et al. 2013; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Szanton et al. 2019; Tinetti et al. 2002) and one non-effective intervention (King et al. 2012). The coordinator or RN involved often provided functional disorder management.

Risk of bias

Findings on the risk of bias are shown in Table 4. The RCTs scored 62% (range 38–92) on average on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Randomised Controlled Trials (Joanna Briggs Institute 2017b), and the CCTs 53% (range 44–56) on the JBI Checklist for Quasi-Experimental (Joanna Briggs Institute 2017a). Four of the twenty studies were judged at low risk of bias (Gitlin et al. 2006; Parsons et al. 2020; Szanton et al. 2019; Tuntland et al. 2015), eleven at moderate risk, and four at high risk (Galik et al. 2015; Lewin et al. 2013; Resnick et al. 2011; Tinetti et al. 2002). No RCT was able to blind participants and delivery personnel to treatment assignment. In seven studies treatment groups were similar at baseline (Galik et al. 2014; Gitlin et al. 2006; Gronstedt et al. 2013; Parsons et al. 2020; Powell et al. 2002; Rooijackers et al. 2021; Tuntland et al. 2015). Risk of bias assessment demonstrated that in all CCTs the effect could also be explained by other exposures or treatments occurring at the same time. In most studies, follow-up was not adequately described and analysed and lacked appropriate statistical analysis. The latter was mainly due to a lack of power.

Overall, within the effective interventions, three studies scored low (Gitlin et al. 2006; Szanton et al. 2019; Tuntland et al. 2015), five scored moderate (Galik et al. 2014; Gitlin et al. 2010; Langeland et al. 2019; Lewin and Vandermeulen 2010; Powell et al. 2002) and two scored high on the risk of bias assessment (Lewin et al. 2013; Tinetti et al. 2002). Within the non-effective interventions, one study scored low (Parsons et al. 2020), seven moderate (Gronstedt et al. 2013; Henskens et al. 2017; Kerse et al. 2008; King et al. 2012; Parsons et al. 2017; Rooijackers et al. 2021; Sackley et al. 2009) and two high on the risk of bias assessment (Galik et al. 2015; Resnick et al. 2011).

Discussion

Using the ReAble definition as a starting point, this systematic review aimed to provide a current overview of reablement interventions internationally and their effect on clients’ daily functioning. Twenty relevant studies from eight countries were included in this systematic review. Ten of these studies were effective in improving ADL functioning. In addition, we intended to identify the most common and possibly promising features in an attempt to "unpack" existing reablement interventions. However, the identification of the most promising features was challenging as an equal amount of effective and non-effective interventions were identified and intervention content was poorly described. Nevertheless, there are some indications that interdisciplinary teams with more diverse disciplines, the use of standardised assessment/goal-setting instruments and four recurring intervention components (i.e. ADL-training, physical and/ or functional exercise, education, management of functional disorders) positively influence the effectiveness of reablement concerning clients’ daily functioning.

Concerning the outcome ADL functioning, we see a great variation in outcome measures used. Roughly, they can be divided into two groups: ADL measures that are goal-oriented and tailored to the individual (e.g. COPM), and more generic ADL measures (e.g. Barthel Index). These generic measures are less sensitive to detect small changes, which is essential when establishing minor improvements in independence (Hartigan 2007). However, combining more subjective measures, like the COPM, with more generic measures, such as the Barthel Index, helps to place the subjective assessment of ADL functioning in the right context (Mlinac and Feng 2016). Unfortunately, in this systematic review it is not possible to conclude how the chosen ADL outcomes have influenced the study findings.

As for factors impacting the effectiveness of reablement, the included studies show that both the size and composition of the interdisciplinary team may influence the effectiveness, with a more diverse team showing more often positive outcomes regarding daily functioning. These positive effects might be explained by the fact that, within a more diverse interdisciplinary team, there is a much broader base of knowledge, skills and resources available, allowing the problem to be approached from more different perspectives (Phillips and O'Reilly 1998). However, with increasing team size, the complexity of interdisciplinary collaboration also increases, especially when it comes to dividing tasks and responsibilities, which makes coordination of teams of utmost importance (Schmutz et al. 2019). In two-thirds of the included interventions, we see that often the RN, OT, and PT are a standard part of the reablement team. These disciplines could be valuable to include in a reablement team due to their educational background. For example, goal setting is part of their curricula and they often have interdisciplinary training, which has shown to contribute towards better collaborative skills and attitudes with other healthcare professions (Reeves et al. 2016; Rossler et al. 2017). Although, due to the differences in educational background, team members also have different values, beliefs, attitudes and behaviours, which emphasises the importance of training in teamwork (Schmutz et al. 2019). Other factors that should be taken into account concerning interdisciplinary collaboration are team familiarity, team members' experience, task complexity and time pressure (Schmutz et al. 2019). Close cooperation and evaluation, as well as time for communication, shared planning and decision making, and goal setting by the client contribute positively to interdisciplinary cooperation (Birkeland et al. 2017).

All included studies used an assessment/goal-setting instrument, as goal setting plays an essential role within reablement. Goal setting involves the client in the decision-making process and ensures that the client's values, autonomy and preferences are respected (Levack 2009; Munthe et al. 2012). However, care professionals often indicate that they lack the knowledge and skills to involve clients in goal setting, that clients are sometimes difficult to motivate, remain passive in the recovery process, and feel overwhelmed to take control of their rehabilitation (Rose et al. 2017). Based on our systematic review there are indications that the use of a standardised assessment/goal-setting tool may lead to more positive outcomes regarding daily functioning. Also, Rose et al. (2017) advise using standardised goal-setting tools to better involve clients in the process (Rose et al. 2017), such as TARGET (Parsons and Parsons 2012) and COPM (Law et al. 1990), which both facilitate the professional to identify activities meaningful to the client and set goals correspondingly. Nevertheless, it remains challenging to set good person-centred goals. To improve goal setting and shared decision, it is also recommended to train both health professionals and clients in shared decision making and the associated communication skills (Rose et al. 2017).

Regarding promising intervention components, it seems like effective interventions contained on average more diverse components. Complex interventions have gained increasing attention over the last years, but their content is often briefly reported or unknown, which makes it difficult to assess their effectiveness and to determine why they work or fail (Smit et al. 2018). Ideally, the modelling and processes of outcomes of complex interventions should be described to identify why the intervention works or does not work (Richards and Hallberg 2015; Smit et al. 2018). This is necessary to understand underlying mechanisms within and between the different intervention components and to properly determine their effectiveness. As addressed earlier, we also had to deal with poor intervention descriptions in many studies. Nevertheless, four possibly promising intervention components were identified.

First, ADL training is a recurring intervention component, which is included in all identified reablement programmes. Within the occupational therapy literature, great benefits are found when ADL training in the elderly population is carried out in their home environment (Liu et al. 2018). The use of home visits or home assessments is recommended to identify problems between the individual's capabilities and the environment. Based on this home assessment, interventions and evaluations can be more tailored and thus increase effectiveness (Liu et al. 2018).

Second, physical and/or functional exercises were also included in each reablement intervention. Mjøsund et al. (2020) studied how physical activity is integrated within reablement programmes. They found that most client goals were set in terms of functional mobility (such as walking, climbing stairs, outdoor walking). These exercises often focus on strength, balance or endurance, but specific details of the programmes were lacking. Liu et al (2018) found that physical exercise is often integrated into ADL training. When exercises are functional, task-specific, and meet client's wishes, they have more favourable outcomes on ADL performance than when they are more structured, constructive and repetitive. (Liu et al. 2018). According to the review by Blankevoort et al. (2010) it is recommended to combine different exercises such as strength, endurance and balance training to improve progress in physical functioning and performance in ADL rather than only providing progressive resistance training. The best results were achieved with the highest training volume. These results are also confirmed by the review by Theou et al. (2011) who looked at managing frailty in older people through exercise. The reviews both emphasise that exercise programmes that last longer than 12 weeks with an intensity of 3 times a week and sessions of 30–45 min produce the best results in functional, physical and psychosocial terms, and help prevent adverse health effects.

Third, education is regularly integrated into (effective) reablement programmes targeting the client and/ or their informal carers. On the one hand, education was given during educational meetings making use of handouts and leaflets, for example on how to motivate clients in daily and physical activities. On the other hand, advice was given by care professionals during regular care moments. Topics of education were, for example, on how to carry out (i) ADL activities, use of (mobility)aids and self-management.

Additionally, management of functional disorders, which is often provided by nurses, was included in five out of six effective interventions. The literature on essential nursing care (Kitson et al. 2010; Kitson and Muntlin Athlin 2013) emphasises the importance of care activities like eating and drinking, comfort (including pain management), safety, prevention and medication. However, this field of nursing care is often overlooked, undervalued and taken for granted, which can have a negative impact on client outcomes (Zwakhalen et al. 2018).

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this review is the process of obtaining the final study selection as a) the entire screening process was conducted independently by two reviewers, b) the final sample was checked and supplemented by experts with a broader view than only geriatrics, c) snowball sampling was used to reduce the risk of missing possible important articles, and d) the search was repeated after one year as the review should be as up to date as possible according to the methodological standards of the Cochrane Collaboration (Chandler et al. 2013). Moreover, grey literature was used to supplement the extracted data when available. The risk of bias assessment is another strength, as the reviewers completed the JBI checklists independently and reached a consensus through discussion in case this was necessary. Our systematic review focused on ADL functioning. Consequently, promising reablement features concerning other outcomes such as physical functioning, quality of life and fewer hospital admissions were not taken into account. Another limitation is that conclusions cannot be confidently drawn, as more than three-quarters of the included studies were of moderate to poor quality which hindered us to exclude the lower quality studies.

Methodological reflection

Reflecting on the capability of the used research design in answering the research questions, this review has been able to provide an overview of current evidence and reflect on the effects on ADL functioning. While we have been able to identify (promising) components of the programmes, we do not yet know much about the details of these components in practice and whether they were implemented as intended. Since the latter is not usually discussed within effect studies, including results of process evaluations could be potentially valuable. In addition, it is suggested to conduct multiple case studies to gather more in-depth information about existing reablement programmes.

Conclusions and practical implications

This study has several important implications for future practice regarding reablement interventions. First, reablement interventions should be delivered by a diverse interdisciplinary team, preferably including nurses, occupational therapists and/ or physical therapists, while attention should be paid to the training and coordination of the team and other factors that influence the quality of interdisciplinary collaboration. Second, reablement interventions should make use of standardised assessment and goal-setting tools, which should be combined with training for both healthcare professionals and clients. Third, promising intervention components are (i) ADL-training, physical and/or functional exercise, education and management of functional disorders.

A start has been made with 'unpacking' reablement; however, the review has only scratched the surface in terms of a better understanding of the determining factors for the effectiveness of reablement interventions. More research is needed to open the black box of reablement. First, more intervention protocols should be published that make use of reporting guidelines such as the TIDieR checklist (Hoffmann et al. 2014) and the use of process evaluations should be emphasised to assess the variation in results of effect studies within the right context (Moore et al. 2015). Second, collecting additional data from reablement experts, who have developed, evaluated and implemented reablement interventions, can provide more in-depth information about available reablement interventions. Third, more high-quality studies using outcomes tailored to the client's goals (e.g. COPM) are needed that aim to identify reablement features that are more promising than others and investigate which combination of features is most effective.

Data availability

Data generated and analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Material availability

Data generated and analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Akl E (2019) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane, London. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119536604

Arnau A, Espaulella J, Serrarols M, Canudas J, Formiga F, Ferrer M (2016) Risk factors for functional decline in a population aged 75 years and older without total dependence: a one-year follow-up. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 65:239–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2016.04.002

Aspinal F, Glasby J, Rostgaard T, Tuntland H, Westendorp RG (2016) New horizons: reablement—supporting older people towards independence. Age Ageing 45(5):572–576. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw094

Birkeland A, Tuntland H, Forland O, Jakobsen FF, Langeland E (2017) Interdisciplinary collaboration in reablement—a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc 10:195–203. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S133417

Blankevoort CG, van Heuvelen MJ, Boersma F, Luning H, de Jong J, Scherder EJ (2010) Review of effects of physical activity on strength, balance, mobility and ADL performance in elderly subjects with dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 30(5):392–402. https://doi.org/10.1159/000321357

Booth A (2008) Unpacking your literature search toolbox: on search styles and tactics. Health Info Libr J 25(4):313–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2008.00825.x

Chandler J, Churchill R, Higgins J, Lasserson T, Tovey D (2013) Methodological standards for the conduct of new Cochrane Intervention Reviews. Sl Cochrane Collaboration 3(2):1–14

Cochrane A, Furlong M, McGilloway S, Molloy DW, Stevenson M, Donnelly M (2016) Time-limited home-care reablement services for maintaining and improving the functional independence of older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010825.pub2

Cooper C, Booth A, Varley-Campbell J, Britten N, Garside R (2018) Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: a literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 18(1):85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0545-3

Covinsky KE, Justice AC, Rosenthal GE, Palmer RM, Landefeld CS (1997) Measuring prognosis and case mix in hospitalized elders. The importance of functional status. J Gen Intern Med 12(4):203–208. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012004203.x

Day T, Tosey P (2011) Beyond SMART? A new framework for goal setting. Curriculum J 22(4):515–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2011.627213

Doh D, Smith R, Gevers P (2019) Reviewing the reablement approach to caring for older people. Ageing Soc 40(6):1371–1383. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0144686x18001770

Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G (2004) Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59(3):255–263. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255

Galik E, Resnick B, Hammersla M, Brightwater J (2014) Optimizing function and physical activity among nursing home residents with dementia: testing the impact of function-focused care. Gerontologist 54(6):930–943. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt108

Galik E, Resnick B, Lerner N, Hammersla M, Gruber-Baldini AL (2015) Function focused care for assisted living residents with dementia. Gerontologist 55(Suppl 1):S13-26. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu173

Gingerich BS (2016) Restorative care nursing for older adults: a guide for all care settings. Home Health Care Manag Pract 19(1):78–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822306292220

Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Corcoran M, Schinfeld S, Hauck WW (2006) A randomized trial of a multicomponent home intervention to reduce functional difficulties in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 54(5):809–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00703.x

Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hodgson N, Hauck WW (2010) A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers: the COPE randomized trial. JAMA 304(9):983–991. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1253

Gronstedt H, Frandin K, Bergland A, Helbostad JL, Granbo R, Puggaard L, Andresen M, Hellstrom K (2013) Effects of individually tailored physical and daily activities in nursing home residents on activities of daily living, physical performance and physical activity level: a randomized controlled trial. Gerontology 59(3):220–229. https://doi.org/10.1159/000345416

Hartigan I (2007) A comparative review of the Katz ADL and the Barthel Index in assessing the activities of daily living of older people. Int J Older People Nurs 2(3):204–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3743.2007.00074.x

Henskens M, Nauta IM, Scherder EJA, Oosterveld FGJ, Vrijkotte S (2017) Implementation and effects of Movement-oriented Restorative Care in a nursing home—a quasi-experimental study. BMC Geriatr 17(1):243. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0642-x

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman DG, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston M, Lamb SE, Dixon-Woods M, McCulloch P, Wyatt JC, Chan A-W, Michie S (2014) Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ Br Med J 348:g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687

Joanna Briggs Institute (2017a) Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies (non-randomized experimental studies). https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

Joanna Briggs Institute (2017b) Checklist for Randomized Controlled Trials. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

Kerse N, Peri K, Robinson E, Wilkinson T, von Randow M, Kiata L, Parsons J, Latham N, Parsons M, Willingale J, Brown P, Arroll B (2008) Does a functional activity programme improve function, quality of life, and falls for residents in long term care? Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 337:a1445. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1445

King AI, Parsons M, Robinson E, Jorgensen D (2012) Assessing the impact of a restorative home care service in New Zealand: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Health Soc Care Community 20(4):365–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01039.x

Kitson A, Conroy T, Wengstrom Y, Profetto-McGrath J, Robertson-Malt S (2010) Defining the fundamentals of care. Int J Nurs Pract 16(4):423–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01861.x

Kitson AL, Muntlin Athlin A (2013) Development and preliminary testing of a framework to evaluate patients’ experiences of the fundamentals of care: a secondary analysis of three stroke survivor narratives. Nurs Res Pract 2013:572437. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/572437

Kitson AL, Muntlin Athlin A, Conroy T (2014) Anything but basic: Nursing’s challenge in meeting patients’ fundamental care needs. J Nurs Scholarsh 46(5):331–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12081

Lafortune (2007) Trends in severe disability among elderly people: assessing the evidence in 12 OECD countries and the future implications. OECD Health Working Papers No. 26. https://doi.org/10.1787/217072070078

Landi F, Tua E, Onder G, Carrara B, Sgadari A, Rinaldi C, Gambassi G, Lattanzio F, Bernabei R, Bergamo S-HSG (2000) Minimum data set for home care: a valid instrument to assess frail older people living in the community. Med Care 38(12):1184–1190. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200012000-00005

Langeland E, Tuntland H, Folkestad B, Forland O, Jacobsen FF, Kjeken I (2019) A multicenter investigation of reablement in Norway: a clinical controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 19(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1038-x

Law M, Baptiste S, McColl M, Opzoomer A, Polatajko H, Pollock N (1990) The Canadian occupational performance measure: an outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther 57(2):82–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749005700207

Legg L, Gladman J, Drummond A, Davidson A (2016) A systematic review of the evidence on home care reablement services. Clin Rehabil 30(8):741–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215515603220

Levack WM (2009) Ethics in goal planning for rehabilitation: a utilitarian perspective. Clin Rehabil 23(4):345–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215509103286

Lewin G, Vandermeulen S (2010) A non-randomised controlled trial of the Home Independence Program (HIP): an Australian restorative programme for older home-care clients. Health Soc Care Community 18(1):91–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00878.x

Lewin G, De San Miguel K, Knuiman M, Alan J, Boldy D, Hendrie D, Vandermeulen S (2013) A randomised controlled trial of the Home Independence Program, an Australian restorative home-care programme for older adults. Health Soc Care Community 21(1):69–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01088.x

Liu CJ, Chang WP, Chang MC (2018) Occupational therapy interventions to improve activities of daily living for community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2018.031252

Metzelthin SF, Rostgaard T, Parsons M, Burton E (2020) Development of an internationally accepted definition of reablement: a Delphi study. Ageing Soc. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0144686x20000999

Microsoft (2016) Excel. In (Version Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2016) Microsoft Coorporation. https://office.microsoft.com/excel

Mjøsund HL, Moe CF, Burton E, Uhrenfeldt L (2020) Integration of physical activity in reablement for community dwelling older adults: a systematic scoping review. J Multidiscip Healthc 13:1291–1315. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S270247

Mlinac ME, Feng MC (2016) Assessment of activities of daily living, self-care, and independence. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 31(6):506–516. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acw049

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, Moore L, O’Cathain A, Tinati T, Wight D, Baird J (2015) Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 350:h1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258

Munthe C, Sandman L, Cutas D (2012) Person centred care and shared decision making: implications for ethics, public health and research. Health Care Anal 20(3):231–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-011-0183-y

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. In Syst Rev (Version 2016/12/07) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27919275

Parsons J, Parsons M (2012) The effect of a designated tool on person-centred goal identification and service planning among older people receiving homecare in New Zealand. Health Soc Care Community 20(6):653–662. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01081.x

Parsons M, Senior H, Kerse N, Chen MH, Jacobs S, Anderson C (2017) Randomised trial of restorative home care for frail older people in New Zealand. Nurs Older People 29(7):27–33. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop.2017.e897

Parsons M, Parsons J, Pillai A, Rouse P, Mathieson S, Bregmen R, Smith C, Kenealy T (2020) Post-acute care for older people following injury: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 21(3):404-409e401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.015

Phillips K, O’Reilly C (1998) Demography and diversity in organizations: a review of 40 years of research. Res Org Behav 20:77–140

Powell J, Heslin J, Greenwood R (2002) Community based rehabilitation after severe traumatic brain injury: a randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 72(2):193–202. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.72.2.193

Reeves S, Fletcher S, Barr H, Birch I, Boet S, Davies N, McFadyen A, Rivera J, Kitto S (2016) A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME Guide No. 39. Med Teach 38(7):656–668. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173663

Resnick B, Galik E, Gruber-Baldini A, Zimmerman S (2011) Testing the effect of function-focused care in assisted living. J Am Geriatr Soc 59(12):2233–2240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03699.x

Resnick B, Galik E, Boltz M (2013) Function focused care approaches: literature review of progress and future possibilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc 14(5):313–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.019

Reuben DB, Solomon DH (1989) Assessment in geriatrics. Of caveats and names. J Am Geriatr Soc 37(6):570–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb05691.x

Richards DA, Hallberg IR (2015) Complex interventions in health: an overview of research methods, 1st edn. Routledge, Abington. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203794982

Rooijackers TH, Kempen G, Zijlstra GAR, van Rossum E, Koster A, Lima Passos V, Metzelthin SF (2021) Effectiveness of a reablement training program for homecare staff on older adults’ sedentary behavior: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17286

Rose A, Rosewilliam S, Soundy A (2017) Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 100(1):65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.030

Rossler KL, Buelow JR, Thompson AW, Knofczynski G (2017) Effective learning of interprofessional teamwork. Nurse Educ 42(2):67–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/nne.0000000000000313

Ryburn B, Wells Y, Foreman P (2009) Enabling independence: Restorative approaches to home care provision for frail older adults. Health Soc Care Community 17(3):225–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00809.x

Sackley CM, van den Berg ME, Lett K, Patel S, Hollands K, Wright CC, Hoppitt TJ (2009) Effects of a physiotherapy and occupational therapy intervention on mobility and activity in care home residents: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 339:b3123. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b3123

Schmutz JB, Meier LL, Manser T (2019) How effective is teamwork really? The relationship between teamwork and performance in healthcare teams: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 9(9):e028280. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028280

Schuurmans M, Lambregts J, Grotendorst A, Merwijk C (2020) Deel 3 Beroepsprofiel verpleegkundige

Sims-Gould J, Tong CE, Wallis-Mayer L, Ashe MC (2017) Reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation and restorative interventions with older adults in receipt of home care: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 18(8):653–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.12.070

Smit LC, Schuurmans MJ, Blom JW, Fabbricotti IN, Jansen APD, Kempen GIJM, Koopmans R, Looman WM, Melis RJF, Metzelthin SF, Moll van Charante EP, Muntinga ME, Ruikes FGH, Spoorenberg SLW, Suijker JJ, Wynia K, Gussekloo J, De Wit NJ, Bleijenberg N (2018) Unravelling complex primary-care programs to maintain independent living in older people: a systematic overview. J Clin Epidemiol 96:110–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.12.013

Szanton SL, Xue QL, Leff B, Guralnik J, Wolff JL, Tanner EK, Boyd C, Thorpe RJ Jr, Bishai D, Gitlin LN (2019) Effect of a biobehavioral environmental approach on disability among low-income older adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 179(2):204–211. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6026

Tessier A, Omi M-D, Beaulieu N, Sc M, Mcgi Nn CA, Née RE, Atulippe L (2016) Effectiveness of Reablement A Systematic Review Efficacité de l’ autonomisation une revue systématique. Healthc Policy 11(4):49–59

Theou O, Stathokostas L, Roland KP, Jakobi JM, Patterson C, Vandervoort AA, Jones GR (2011) The effectiveness of exercise interventions for the management of frailty: a systematic review. J Aging Res 2011:569194. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/569194

Tinetti ME, Baker D, Gallo WT, Nanda A, Charpentier P, O’Leary J (2002) Evaluation of restorative care vs usual care for older adults receiving an acute episode of home care. JAMA 287(16):2098–2105. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.16.2098

Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L (2020) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Vol. Chapter 3: Systematic Reviews of Effectiveness). https://doi.org/10.46658/jbimes-20-04

Tuntland H, Aaslund MK, Espehaug B, Forland O, Kjeken I (2015) Reablement in community-dwelling older adults: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 15:145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0142-9

Whitehead PJ, Worthington EJ, Parry RH, Walker MF, Drummond AE (2015) Interventions to reduce dependency in personal activities of daily living in community dwelling adults who use homecare services: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil 29(11):1064–1076. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215514564894

Wohlin C (2014) Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering—EASE '14

Zwakhalen SMG, Hamers JPH, Metzelthin SF, Ettema R, Heinen M, de Man-Van Ginkel JM, Vermeulen H, Huisman-de Waal G, Schuurmans MJ (2018) Basic nursing care: the most provided, the least evidence based—a discussion paper. J Clin Nurs 27(11–12):2496–2505. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14296

Funding

This work was supported by the Living Lab in Ageing and Long-Term Care (Maastricht University) and Stichting Cicero Zorggroep.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by LB and SM, while SZ resolved screening disagreements. The first draft of the manuscript was written by LB. SM, SV, RK and SZ supervised the study and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Matthias Kliegel

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Buma, L.E., Vluggen, S., Zwakhalen, S. et al. Effects on clients' daily functioning and common features of reablement interventions: a systematic literature review. Eur J Ageing 19, 903–929 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-022-00693-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-022-00693-3