Abstract

Aim

This study evaluated the impact of a web-based nudging intervention aimed at reducing alcohol consumption among Danish university bachelor and master students.

Methods

To evaluate the impact of the intervention, we conducted a clustered randomized controlled experiment among 961 university students. The intervention combined a survey on self-affirmation to reduce defensive progression with information on key beliefs about binge drinking and tools to avoid excessive drinking. We measured the impact of the intervention on outcomes using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test scale capturing key aspects of youth drinking.

Results

Compared to the students in the control group, the students in the intervention group had a 20% reduction on number of episodes per month with alcohol intake. We find no effect on binge drinking or measures of harmful alcohol consumption.

Conclusions

Our study shows that it is possible to change young people’s alcohol consumption through a relatively cost-effective web-based intervention based on the theory of planned behavior.

Clinical trial registration

The trial was registered at the American Economic Association’s registry for randomized trials with RCT ID: AEARCTR-0004703. https://www.socialscienceregistry.org/trials/4703

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In most Western countries, alcohol use typically begins during adolescence, with many young people developing an early pattern of binge drinking, i.e., drinking more than five drinks on one occasion (Kuntsche and Labhart 2012; Kuntsche et al. 2004). Young people’s alcohol use tends to accelerate in the late teens, peak in the early 20s, and decrease in the late 20s (Andrade 2019). However, university students often maintain a high level of alcohol consumption up until their late 20s (Van Hal et al. 2018; Karam et al. 2007). While most students will not experience negative consequences for later life outcomes, students who drink heavily expose themselves to immediate risks, such as low academic performance, physical injuries, traffic accidents, and unwanted or unprotected sexual encounters (Andrade and Järvinen 2017; Porter and Pryor 2007; Hingson et al. 2002; Wechsler et al. 1994).

When asked in surveys and qualitative interviews about their alcohol consumption, university students tend to refer to a distinctive drinking culture that includes two motivational factors (Lannoy et al. 2017; Järvinen et al. 2018; Measham and Brain 2005; Kuntsche et al. 2005; Demers et al. 2002). The first motivational factor is that alcohol use helps dealing with stress, coping with personal problems, and relieving boredom (Mohr et al. 2005). The second motivational factor is that alcohol facilitates socialization. As most young people experience starting university as a major transition, alcohol plays a vital role in the transition as the organizing driver for new students to meet and bond with the other students (Utpala-Kumar and Deane 2012; Dempster 2011). Many university students find it difficult to go against the dominant drinking culture (Supski and Lindsay 2017). As drinking too much—or too little—can lead to low popularity among peers, the new students quickly learn the “right” way to drink alcohol (Fjær and Pedersen 2015; Østergaard 2009).

Research suggests that young people’s drinking cultures are formed by a multiplicity of actors, including peers, family members, university authorities, policymakers, and the alcohol industry (Savic et al. 2016; Room 1992). Governmental interventions, such as increasing taxes and reducing the availability of alcohol, have previously been shown to reduce the overall level of alcohol consumption (Anderson et al. 2009; Stockwell 2001). Nevertheless, experiences from past interventions aimed at changing the student drinking show that social norms are not easily changed and that most students view binge drinking as a cornerstone of university life (Kypri et al. 2018; Anderson and Baumberg 2006). Research reveals that social norms are among the best predictors of college student drinking (Neighbors et al. 2007; Fairlie et al. 2021; Lewis and Neighbors 2006). Thus to reduce students’ alcohol consumption, it is important not only to focus on how the individual consumes alcohol but also how the consumption pattern is embedded in a network of friendships with a similar drinking culture. Previous research suggests that social norms may negatively affect students’ participation and outcome in interventions targeting behavioral strategies (Larimer et al. 2007; Barnett et al. 2007).

Extensive literature shows that web-based alcohol interventions are an effective and cost-efficient tool to successfully change alcohol-related behavior among young people (Martinez-Montilla et al. 2020; Riper et al. 2010; Donoghue et al. 2014; Bannink et al. 2014; Schulz et al. 2013; Bewick et al. 2008). However, few web-based alcohol interventions combine randomized control trials with elements that target the young people’s drinking culture (Riper et al. 2010; Haug et al. 2012; Bendtsen et al. 2012; White et al. 2010; Cooke et al. 2016). A recent web-based UK intervention targeting first-year university students is a notable exception. On the basis of the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1988), the researchers combined text messages and “if–then” plans to significantly reduce the frequency of the first-year university students’ binge drinking and change their cognitions about binge drinking (Norman et al. 2018).

The aim of this study was to develop, implement, and evaluate a web-based intervention aimed at reducing alcohol consumption among university students. Compared to previous web-based interventions that tend to focus on first-year students only, this study included students at all levels at the university. The intervention was hereby targeting both bachelor and master students’ engagement with and attitudes toward the dominant drinking culture at the university. We implemented the intervention in Denmark, which constitutes a highly useful case for targeting student drinking. Together with their British counterparts, Danish university students are among the heaviest drinkers in Europe (Järvinen and Room 2007). As the level of alcohol consumption among young people in most of Europe has been converging since the early 2000s (Kraus et al. 2020), additional knowledge about the Danish youth is likely valuable to peer groups in other countries.

Compared to the web-based interventions in previous studies, this intervention was relatively short (answering the questionnaire takes no more than 15 min). Drawing on the theory of planned behavior, the intervention included three different elements focusing on pre-commitment strategies, social norms, and reminders. A central element in the development of the intervention was the collaboration with the local student organizations to adapt the intervention to the current social norms of campus. We hypothesized that the participating students would report improvements in self-reported measures about their alcohol consumption.

Method

Design

In this study, we conducted a stratified randomized control experiment among students from Aarhus University in Denmark. The participants were stratified by both gender and their answer to the question “how often have you been drinking five or more standard drinks at one event during the preceding month?” and randomly assigned to either a control or an intervention group. The trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Danish Centre for Social Science Research on September 16, 2019, and registered prior to the implementation on September 24, 2019, in the American Economic Association’s registry for randomized trials with RCT ID: AEARCTR-0004703. No significant changes were made between the start of the trial and the registration confirmation.

Participation

The participants were recruited by the student association at Aarhus University over 2 weeks between September 11 and September 25, 2019 (see Appendix 1 for a detailed description of the recruitment channels). To be eligible for the experiment, the students had to meet four criteria: be a student at Aarhus University, drink alcohol (answer “yes” to the question “Do you ever drink alcohol?”), sign up voluntarily, and provide a valid phone number. The participants signed up online via a questionnaire that asked them for background information, including their drinking behavior, and background characteristics such as gender, age, and parents’ education. The participants received a follow-up questionnaire 2 months after the intervention had started. To increase participation, we offered a lottery in which the students could win tickets to concerts or the movies.

The study sample size was determined using an effect size of 32 g (means of 176 and 199) alcohol per week, standard deviations of 100 g per week, statistical power of 0.80 at a 2-sided significance level of an alpha of 0.05. This power calculation resulted in 310 participants (50% in treatment and 50% in control group). As the participants were registered automatically, as soon as they answered the first questionnaire, and as there were no marginal cost of including more participants, we end up oversampling participants.

The intervention

The intervention included a link to an online questionnaire and to three short text blocks followed by videos. The students in the intervention group received a text message by SMS and an e-mail with the link. Furthermore, to remind the students about the content of the intervention, three text messages were sent out by SMS. While inspired by a validated self-affirmation questionnaire and a web-based intervention in the UK (Stock et al. 2009), the online questionnaire and short text blocks and videos was adapted to the local Danish university setting. The text messages send out by SMS were developed specifically for this study. Both the questionnaire, and use of text blocks, videos, and text messages draw on a well-established technique, nudging, that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without using either prohibition or economic incentives. We used three sets of nudging tools—pre-commitment strategies, social norms, and reminders—aimed at enhancing the students’ self-control and self-image, and thereby reduce the alcohol consumption.

Pre-commitment strategies help people reflect on their behavior and commit to a certain course of action. Following Gollwitzer (1999), Hagger et al. (2012), and Norman et al. (2018), we included pre-commitment in the intervention by focusing on implementation intentions. The students were asked to specify “if–then” plans, targeting critical situations in the process toward the desired goal. Thus, the students were asked to write a strategy for how they plan to avoid getting drunk in a specific situation.

We used social norms in the intervention by using the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1988), which focuses on beliefs as the primary determinant of individual behavior. Inspired by Norman et al. (2018), the three text blocks and videos focused on the extent to which the students differed from one another relative to three beliefs about drinking behaviors at the university: (a) that social events at the university always include alcohol consumption, (b) that irresponsible drinking behavior does not necessarily affect ones studies, and ©) that most university students drink large amounts of alcohol. In the intervention, each belief is presented with a text block explaining why it is not necessarily true, in combination with a short video in which fellow students talk about their contradictory beliefs and explain what they do to avoid heavy drinking.

For the first belief, the students were introduced to alternative social activities at either the university or in the city, activities that do not include alcohol consumption. For the second belief, the students were presented with fact-based information about the negative effects of alcohol consumption on academic performance. For the third belief, the students were presented with studies showing that most university students drink responsibly. The students were also given reasons for avoiding heavy drinking.

The final element in the intervention was three reminders, sent as text messages to the students’ cell phones. The text messages are intended to remind the student of the specific elements of the intervention. For example, the text message referring to the “if–then” plan reads “It can sometimes be a good idea to make a plan for how much to drink when going to a party to avoid bad experiences. Have you thought about how much you want to drink at the next party you are going to?” Reminders have proven to be a simple but effective tool for combating procrastination, laziness, and forgetfulness, and for completing obligations (Sunstein 2014). For sending out reminders, the timing is essential. In our study, the messages were sent at 2:00 p.m. on three Fridays as this is the time where most student bars begin.

The web-based intervention included insights from self-affirmation theory (Steele 1988), which posits that individuals may protect their self-integrity by ignoring messages targeting their behavior. To prevent students from ignoring our text messages, we used self-affirmation manipulation to reduce defensive processing (Harris and Epton 2009). We introduced the self-affirmation manipulation through a version of the Values in Action Strength Scale, adapted for the Danish setting, and sent it to all participants (Napper et al. 2009). We hypothesized that, as they answered the questionnaire, the students would become more familiar with their positive strengths and thus be more open to suggestions for self-improvement.

Measures

We investigated the effects of the intervention on four individual outcomes related to alcohol consumption: (a) the number of times the student drank alcohol during the preceding month, (b) the number of times the student had been binge drinking alcohol during the preceding month (i.e., drinking more than five standard drinks at one event), (c) the total number of alcoholic drinks the student consumed on a typical day when drinking during the preceding month, and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) score based on the three questions (Higgins-Biddle and Babor 2018). We include both the total AUDIT score and three items of the AUDIT score as outcome measures, as we believe that the specific item carries valuable information about drinking behavior that is masked by total score. All outcomes are measures 2 months after starting the intervention.

Besides information on alcohol, drinking patterns, and reasons for drinking, the survey included questions about age, gender, immigrant status, region of residence, parental education, self-rated health, smoking behavior, drug use, and their study program. We collected the additional background to (1) check for balance between intervention and control group, (2) study the attrition out for the experiment, and (3) compare the intervention sample with the average student at the university.

Statistical analysis

The randomization of participants into the intervention group and the control group by strata (i.e., gender and answers to the survey question “How often have you had five or more standard drinks at one event during the preceding month?”) were performed using the RAND function in SAS. The primary analysis where conducted using the REGRESS command in Stata. We used ordinary least square regression models, where the strata are included as controls. We estimated the average effect of the intervention and applied robust standard errors for each of the four outcomes. We conduct both intention-to-treat and complete case analysis for each outcome. This amounts to a total of eight tests. P values were computed accounting for multiple hypothesis testing (eight tests) using the method proposed in List et al. (2019). We use the Stata package ice (MICE, Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations) for imputations of missing data for the intention-to-treat analysis. Details on the imputation procedure is available in Appendix 2.

Results

Participation flow

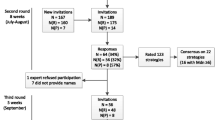

In total, 961 students signed up for participation. Figure 1 illustrates the participant flow. The intervention was sent to 480 participants of whom 225 responded to the follow-up survey. In the control group, 284 participants responded to the follow-up survey. The complete case sample comprised 458 participants, implying a drop-out rate of 0.52. The intention-to-treatment sample includes all initial 961 participants.

Descriptive statistics

As part of the analysis, we have performed detailed descriptive statistics between various relevant subsamples in three steps. In the first step, we began by testing the balance between the treatment and control group in the complete case sample. Table S3.1 in Appendix 3 presents the descriptive statistics on the complete case sample for the treatment and control group. The control group consist of 63% (160/254) women and the average age is 23.8 (SD 2.7) years. Furthermore, for the control group, average number of times drinking alcohol during the past month is 5.4 (SD 3.9), average number of times binge drinking during the past month is 3.2 (SD 3.0), and the average number of standard drinks on a day drinking alcohol during the past month is 5.8 (SD 2.7). The treatment and control group do not differ significantly on these characteristics.

In the second step of our descriptive analysis, we examined sample selection out of the experiment. This involved testing whether the group of students who answered the follow-up surveys differed from those who did not (results can be found in Table S3.2 in Appendix 3). Among the 29 variables included in the analysis, only two yielded p values less than .10, and none had a p value below 0.05. These findings suggest that students did not systematically opt out of the experiment.

As a third and final step of our descriptive analyses, we compared the participants in the experiment to the full population of students at Aarhus University. The results, available in Table S3.3 in Appendix 3, show that students who participated in the experiment are on average two years older that the average student in the full student population and 10% points more likely to be a woman.

Fidelity

Appendix 4 includes an implementation fidelity study, the results of which show that 56.7% (272/480) of the students in the intervention group completed the online intervention: 298 students (62.1%) opened the link and answered at least one question, 287 students (59.8%) answered all questions, and 272 students (56.7%) wrote down a behavioral strategy (see Table S4.1). While we only have counts on video views for the full group, we know that for each time the video was started, 71-77% of the students watched the video to the end; 45.6% (219/480) answered question on the treatment intensity linked to the follow-up questionnaire for the intervention group. They answered that they on average read 2.4 (SD 0.8) of the three text messages: only 6 students read zero text messages, 25 students read 1 message, 44 students read 2 messages, and the majority, 127 students, read 3 messages. The intervention made the majority of the students think more seriously about their alcohol consumption (146/219, 66.7%).

Alcohol consumption

Table 1 presents the effect of the intervention on four measures of alcohol consumption: the AUDIT score, the number of times the student had drunk alcohol during the preceding month, the number of times the student had been binge drinking during the preceding month, and the typical number of drinks on a day when the student was drinking alcohol within the preceding month. The estimations in Table 1 are conditioned on the strata, i.e., baseline information on gender at answers to the question “How often have you had five or more standard drinks at one event during the preceding month?”

In Table 1, we show the outcome means for the complete case sample for the treatment and the control group. For the outcomes AUDIT score and number of times drinking alcohol during the past week the outcome means where larger for the control group than the treatment group. For the outcome “number of times binge drinking during the past month” the outcome means were the same for treatment and control group and for the outcome measuring the typical number of drinks on a day drinking alcohol, the treatment group has a higher outcome mean than the control group. The regression results in Table 1 show that the intervention had a significant effect on the number of times the student drank alcohol during the preceding month. As the control and intervention group are similar at baseline (see Table S3.1 in Appendix 3), the estimated effects in Table 1 show that the effect of the intervention was a reduction in the number of times the students drank alcohol during the preceding month by almost one time (intention-to-treat estimate: mean −0.94, P = .03; compete case estimate: mean −0.87, P = .049), corresponding to a reduction of 17.0% for the intention-to-treat estimate and 15.6% for the complete case. This calculation is based on the average number of times the control group drank alcohol during the preceding month (5.58). We find no significant effect of the intervention on the three other measures of alcohol consumption, i.e., AUDIT score, binge drinking, and number of drinks on a day drinking alcohol.

To control for the students’ baseline drinking behavior and sociodemographic background, we also ran regression with 35 variables measuring, besides baseline drinking behavior, aspects such as age, ethnicity, parental educational background, experience with illegal substances, and variables for motivational factors (for complete list of variables see Table S5.1 in Appendix 5). Results of the regression model can also be found in Table S5.1, which shows similar results to the ones presented in Table 1. Furthermore, we found no effect on harmful alcohol consumption, see Table S5.2 in Appendix 5. On the basis of cost-effectiveness calculations, which can be found in Table S6.1 in Appendix 6, our intervention is relatively inexpensive. We estimated the cost for reducing the frequency of drinking by one per month is between 14 and 28 Euros.

Discussion

Main findings of this study

The aim of this intervention study is to test whether a web-based intervention, making use of various nudging tools, can reduce alcohol consumption among university students. The intervention included both a questionnaire, text including videos of peers telling, among other things, about life at the University without drinking alcohol, a written down strategy to opt out of drinking, and reminders of the intervention. As the elements in the intervention were not randomized, we can only evaluate the total effect of the intervention, including all elements. However, we find that most of the students received the intervention and that most of the students found liked or were neutral about the intervention. The intervention was tested on Danish university students who are among the heaviest drinkers in Europe. We conducted a stratified randomized controlled trial that provided a group of students with tools that helped them to make pre-commitment strategies to avoid getting drunk and to change their views on social norms that result in excessive alcohol intake. The intervention significantly reduced the number of times the students drank alcohol during the preceding month. The intention-to-treat estimate corresponds to a reduction of 17.0% in the number of times the students drank alcohol. The result is virtually the same in the complete case analysis and robust to multiple hypothesis testing.

While the number of times the students drank alcohol was reduced, the number of drinks when drinking was not changed. One explanation for this result could be that, as the question is retrospective, it may be easy for the students to remember if they did not drink alcohol, while it may be difficult to remember how many drinks they consumed. Thus, we might expect a higher measurement error in the variables measuring the number of drinks compared to whether they drank or not. However, another explanation could be that the students continue to consume the same number of drinks when they drink, or that the times they do not drink anymore were the times when they drank few drinks. In the latter case, we would expect to see an increase in the average number of drinks when they drink. In fact, the results show a small, but insignificant, increase in the number of drinks when they drink.

The study demonstrates the cost-effectiveness of an easy-to-implement web-based intervention, targeting the individuals’ engagement with and attitudes toward the dominant drinking culture, for reducing alcohol consumption among university students. Compared to most web-based health interventions, our intervention was relatively short (answering the questionnaire takes no more than 15 min).

While the intervention had only a significant effect on one of the drinking variables, i.e., number of times drinking alcohol per month, at a 2-month follow-up, these short-term changes indicate that providing students with simple psychological tools can enhance their abilities to go against the dominant drinking culture. Implementation of the study requires access to the students’ mobile number, which may not be possible in other settings. However, the intervention could be implemented by using any kind of platform, e.g., school managed IT platforms or through e-mails.

The overall result is important for making the environment among university students not only healthier but also more inclusive for students from different cultural backgrounds. Nonetheless, more research is needed for understanding the complex relationship between the many actors that create, maintain, and change drinking cultures in higher education. This study provides a first step toward making young people more aware of their preferences and thereby reduce their alcohol consumption.

What is already known on this topic

In most Western countries, excessive alcohol intake among university students is a cause of concern. Previous research has shown that inventions aimed at changing the social norms and behaviors that affect young people’s drinking can be both expensive and time consuming, as they typically involve targeting various actors beyond the young people, including family members, university authorities, policymakers, and the alcohol industry. In an intervention similar to ours, tested on British university students, a study by Norman et al. (2018) finds that the students that received treatment significantly reduced their frequency of units of alcohol consumed, binge drinking, and the AUDIT score compared to the control group. The study does not, however, report the impact on the number of times the students drank alcohol.

What this study adds

We demonstrated that simple nudging tools grounded in the theory of planned behavior can help young people in reducing their alcohol consumption. Our study hereby adds to the growing line of research utilizing nudging techniques, particularly within the framework of theory of planned behavior, aimed at altering young people’s drinking culture (Norman et al. 2018). We found no effect on binge drinking, the number of drinks per event and AUDIT score. The difference in our findings compared to Norman et al. (2018) can be due to the dominant drinking culture at the Danish university, which seems difficult to change, and the fact that we include university students at all levels and not only first-year students. While older students are likely to have developed appropriate protective strategies against alcohol interventions, first-year students are less embedded in the social norms and practices of the drinking culture and may be more likely to comply with the intervention (Tanner-Smith and Lipsey 2015; Moreira et al. 2009). Still, while we only find significant effects on the number of times the students drank alcohol, the average number of standard drinks on a day drinking alcohol during the past month was 5.8 for the control group, i.e., more than five drinks as is the definition of binge drinking. More research is needed to understand how web-based interventions work among young people with different drinking cultures.

Limitations

The study has limitations. First, it relies on self-reported measures. Although the intervention is based on validated measures, they are still subject to response bias and may potentially inflate the parameter estimate in the statistical analyses. In addition, the retrospective approach—asking the students about past alcohol-related events, such as those used in the study—has also been shown to be a potential source of bias (Järvinen et al. 2018). Second, as in all panel studies, our study suffers from attrition. Nonetheless, we find comparable estimates in the complete case and the intention-to-treat analysis. Third, our study involves a relatively small sample size. Therefore, we cannot provide more detailed information about the intervention and control groups by, for example, dividing the intervention group into subgroups with distinctive characteristics relative to more detailed patterns of drinking, specific fields of study, parental background, or other such subgroups.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ajzen I (1988) Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Dorsey, Homewood

Anderson P, Chisholm D, Furh DC (2009) Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet 373:2234–2246

Anderson P, Baumberg B (2006) Alcohol in Europe: a public health perspective. Institute of alcohol studies, London

Andrade SB (2019) The temporal rhythm of alcohol consumption: on the development of young people’s weekly drinking patterns. Young 27:225–244

Andrade SB, Järvinen M (2017) More risky for some than others: negative life events among young risk-takers. Health Risk Soc 19(7–8):387–410

Bannink R, Broeren S, Joosten-van Zwanenburg E, van As E (2014) Effectiveness of a web-based tailored intervention (E-health4Uth) and consultation to promote adolescents’ health: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 16:e143

Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM (2007) Efficacy of counselor vs. computer-delivered intervention with mandated college students. Addict Behav 32:2529–2548

Bendtsen P, McCambridge J, Bendtsen M, Karlsson N (2012) Effectiveness of a proactive mail-based alcohol Internet intervention for university students: dismantling the assessment and feedback components in a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 14:e142

Bewick BM, Trusler K, Barkham M, Hill AJ (2008) The effectiveness of web-based interventions designed to decrease alcohol consumption–a systematic review. Prev Med 47:17–26

Bewick BM, West R, Gill J, O’May F (2010) Providing web-based feedback and social norms information to reduce student alcohol intake: a multisite investigation. J Med Internet Res 12:e59

Cooke R, Dahdah M, Norman P, French DP (2016) How well does the theory of planned behaviour predict alcohol consumption? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev 10:148–167

Demers A, Kairouz S, Adlaf EM, Gliksman L (2002) Multilevel analysis of situational drinking among Canadian undergraduates. Soc Sci Med 55:415–424

Dempster S (2011) I drink, therefore I’m man: gender discourses, alcohol and the construction of British undergraduate masculinities. Gender Educ 23:635–653

Donoghue K, Patton R, Phillips T, Deluca P (2014) The effectiveness of electronic screening and brief intervention for reducing levels of alcohol consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 16:e142

Fairlie AM, Lewis MA, Waldron KA, Wallace EC (2021) Understanding perceived usefulness and actual use of protective behavioral strategies: the role of perceived norms for the reasons that young adult drinkers use protective behavioral strategies. Addict Behav 112

Fjær EG, Pedersen W (2015) Drinking and moral order: drunken comportment revisited. Addict Res Theory 23:449–458

Gollwitzer PM (1999) Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. Am Psychol 54:493–503

Hagger MS, Lonsdale A, Koka A, Hein V (2012) An intervention to reduce alcohol consumption in undergraduate students using implementation intentions and mental simulations: a cross-national study. Int J Behav Med 19:82–96

Harris PR, Epton T (2009) The impact of self-affirmation on health cognition, health behaviour and other health-related responses: a narrative review. Social Personal Psychol Compass 3:962–978

Haug S, Sannemann J, Meyer C, John U (2012) Internet and mobile phone interventions to decrease alcohol consumption and to support smoking cessation in adolescents: a review. Gesundheitswesen 74:160–177

Higgins-Biddle JC, Babor TF (2018) A review of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), AUDIT-C, and USAUDIT for screening in the United States: past issues and future directions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 44:578–586

Hingson RW, Heeren T, Zakocs RC, Kopstein A (2002) Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24. J Stud Alcohol 63:136–144

Järvinen M, Room R (2007) Youth drinking cultures: European experiences. Routledge, London

Järvinen M, Andrade SB, Østergaard SV, Demant J (2018) Unge, alkohol og stoffer: Et 10-årigt forløbsstudie. Copenhagen University, Copenhagen

Karam E, Kypri K, Salamoun M (2007) Alcohol use among college students: an international perspective. Curr Opin Psychiatry 20:213–221

Kraus L, Room R, Livingston M, Pennay A, Holmes J, Törrönen J (2020) Long waves of consumption or a unique social generation? Exploring recent declines in youth drinking. Addict Res Theory 28(3):183–193

Kuntsche E, Labhart F (2012) Investigating the drinking patterns of young people over the course of the evening at weekends. Drug Alcohol Depend 124:319–324

Kuntsche E, Rehm J, Gmel G (2004) Characteristics of binge drinkers in Europe. Soc Sci Med 59:113–127

Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R (2005) Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clin Psychol Rev 25:841–861

Kypri K, Maclennan B, Cousins K, Connor J (2018) Hazardous drinking among students over a decade of university policy change: controlled before-and-after evaluation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(10):2137

Lannoy S, Billieux J, Poncin M, Maurage P (2017) Binging at the campus: motivations and impulsivity influence binge drinking profiles in university students. Psychiatry Res 250:146–154

Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano PM (2007) Personalize d mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 75:285–293

Lewis MA, Neighbors C (2006) Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: a review of the research on personalized normative feedback. J Am Coll Health 54:213–218

List JA, Shaikh AM, Xu Y (2019) Multiple hypothesis testing in experimental economics. Exp Econ 22:773–793

Martinez-Montilla JM, Mercken L, de Vries H, Candel M (2020) A web-based, computer-tailored intervention to reduce alcohol consumption and binge drinking among Spanish adolescents: cluster randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 22:e15438

Measham F, Brain K (2005) ‘Binge’ drinking, British alcohol policy and the new culture of intoxication. Crime, Media, Culture 1:262–283

Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Temple M (2005) Moving beyond the keg party: a daily process study of college student drinking motivations. Psychol Addict Behav 19:392–403

Moreira MT, Smith LA, Foxcroft D (2009) Social norms interventions to reduce alcohol misuse in university or college students. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8(3)

Napper L, Harris PR, Epton T (2009) Developing and testing a self-affirmation manipulation. Self Identity 8:45–62

Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N (2007) Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? J Stud Alcohol Drugs 68:556–565

Norman P, Cameron D, Epton T, Webb TL (2018) A randomized controlled trial of a brief online intervention to reduce alcohol consumption in new university students: combining self-affirmation, theory of planned behaviour messages, and implementation intentions. Br J Health Psychol 23:108–127

Østergaard J (2009) Learning to become an alcohol user: adolescents taking risks and parents living with uncertainty. Add Res Theory 17:30–53

Porter SR, Pryor J (2007) The effects of heavy episodic alcohol use on student engagement, academic performance, and time use. J College Student Dev 48:455–467

Riper H, Andersson G, Christensen H, Cuijpers P (2010) Theme issue on e-mental health: a growing field in internet research. J Med Internet Res 12:e74

Room R (1992) The impossible dream?–Routes to reducing alcohol problems in a temperance culture. J Subst Abuse 4:91–106

Savic M, Room R, Mugavin J, Pennay A (2016) Defining “drinking culture”: a critical review of its meaning and connotation in social research on alcohol problems. Drugs: Educ 23:270–282

Schulz DN, Candel MJ, Kremers SP, Reinwand DA (2013) Effects of a web-based tailored intervention to reduce alcohol consumption in adults: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 15:e206

Steele CM (1988) The psychology of self-affirmation: sustaining the integrity of the self. Adv Exp Social Psychol 21:261–302

Stock C, Mikolajczyk R, Bloomfield K, Maxwell AE (2009) Alcohol consumption and attitudes towards banning alcohol sales on campus among European university students. Public Health 123:122–129

Stockwell T (2001) Effects of price and taxation. In: Heather N, Peters TJ, Stockwell T (eds) International handbook of alcohol dependence and problems. Wiley, New York, pp 685–698

Sunstein CR (2014) Why nudge?: the politics of libertarian paternalism. Yale University Press, New Haven

Supski S, Lindsay J (2017) ‘There’s something wrong with you’: how young people choose abstinence in a heavy drinking culture. Young 25:323–338

Tanner-Smith EE, Lipsey MW (2015) Brief alcohol interventions for adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Subs Abuse Treatment 51:1–18

Utpala-Kumar R, Deane FP (2012) Heavy episodic drinking among university students: drinking status and perceived normative comparisons. Subst Use Misuse 47:278–285

Van Hal G, Tavolacci MP, Stock C, Vriesacker B (2018) European University students’ experiences and attitudes toward campus alcohol policy: a qualitative study. Subst Use Misuse 53:1539–1548

Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B (1994) Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college. A national survey of students at 140 campuses. JAMA 272:1672–1677

White A, Kavanagh D, Stallman H, Klein B (2010) Online alcohol interventions: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 12:e62

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Danish Centre Of Applied Social Science The intervention was financed by Aarhus Municipality and Carlsberg in Denmark. The sponsors were not involved in the research design, evaluation, or interpretation of the results. The Danish Center for Social Science Research financed the preparation of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Stefan Bastholm Andrade: Creating the research design, searching for literature, analyzing the literature, collecting and/or preparing data, describing the results, writing up the paper, reviewing and commenting on the written paper and approving the final version of the paper.

Jane Greve: Creating the research design, searching for literature, analyzing the literature, collecting and/or preparing data, describing the results, writing up the paper, reviewing and commenting on the written paper and approving the final version of the paper.

Rune Vammen Lesner: Creating the research design, searching for literature, analyzing the literature, collecting and/or preparing data, describing the results, writing up the paper, reviewing and commenting on the written paper and approving the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical statement

The study protocol and trial information have been evaluated and approved by the Internal Review Board at the Danish Center for Social Science Research. Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Participants were provided with clear information about the nature and purpose of the research, as well as any potential risks or benefits associated with their participation. Measures were taken to ensure the confidentiality and anonymity of participants, and their right to withdraw from the study at any time was respected. Furthermore, the study upholds the principles of integrity, transparency, and fairness in all aspects of the research process. Any conflicts of interest or biases that may influence the research findings have been disclosed and addressed.

Ethics approval

The study has been subject to a Human Subjects Protection Review and was approved by the Internal Review Board at the Danish Center of Social Science and Research September 12, 2019.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Andrade, S.B., Greve, J. & Lesner, R.V. Changing university students’ alcohol use with a web-based intervention: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. J Public Health (Berl.) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-024-02302-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-024-02302-2