Abstract

Aim

This scoping review explores key concepts related to the prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation of COVID-19, offering insights for future pandemic preparedness and response strategies.

Subject and methods

A scoping review was conducted using electronic databases including PubMed, EBSCO (CINAHL, APA PsycINFO), and Cochrane. The results were filtered for papers published in English, German, Italian, Spanish, and Dutch until 31 December 2022. Eighty-one articles were selected for the scoping review. Moreover, gray literature on guidelines was retrieved from reports by each country’s main institution for pandemic management, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Results

From the analyzed articles several key points emerged, highlighting main issues facing the COVID-19 pandemic. The challenges in prevention include emphasizing airborne precautions, addressing diverse adherence to social distancing, and overcoming challenges in digital contact tracing. In the realm of treatment, essential considerations include personalized patient management and the significance of holistic care. Rehabilitation efforts should prioritize post-COVID conditions and explore suggested management models. Addressing the social impact involves recognizing psychological effects, advocating for quality improvement initiatives, and for the restructuring of public health systems.

Conclusion

This scoping review emphasizes the profound impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the global and European population, resulting in a significant death toll and widespread long-term effects. Lessons learned include the critical importance of coordinated emergency management, transparent communication, and collaboration between health authorities, governments, and the public. To effectively address future public health threats, proactive investment in infrastructure, international collaboration, technology, and innovative training is crucial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan and soon became a global public health issue (Lai et al. 2020; Wu and McGoogan 2020). The coronavirus disease, or COVID-19, causes flu-like symptoms such as fever, dry cough, dyspnea, and fatigue and can lead to life-threatening pneumonia (Choi et al. 2020). The clinical spectrums range widely from asymptomatic infections to severe illness. Up to 80% of those infected by the virus could have had no symptoms or mild to moderate symptoms (WHO 2020, 2023). Severe illness and death were more likely to occur with increasing age and comorbidities (WHO 2020). By June 2023, the COVID-19 pandemic had resulted in 6.94 million deaths globally, according to the World Health Organization (WHO Data 2023). In Europe alone, there were 276 million confirmed cases and 2.24 million deaths during the various pandemic waves between February 2020 and January 2022 (Mathieu et al. 2020). Italy and Spain reported a higher number of deaths than Germany and the Netherlands, as European countries were impacted significantly in different ways and times. Various parameters and reporting structures were introduced at both national and international levels to quickly identify and minimize the impact of the virus (Gabutti et al. 2021). Table 1 shows the impact of the pandemic in four European countries.

Prevention

In the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, controlling the spiraling infection rates took precedence. To prevent the spread of the coronavirus, several protective measures were introduced, such as wearing masks in public, hand hygiene and disinfection, and ventilation of public areas and objects. Moreover, social distancing was implemented through restrictions on personal mobility. Further measures included border control and closure of public transport, workplaces, and schools, isolation of cases, contact tracing, screening testing, and quarantine.

Although physical distancing was the primary measure adopted by many European governments at the onset of the pandemic, public compliance with these measures varied significantly. Mortality and virus transmission rates in relation to social distancing measures (particularly lockdown) showed a decrease in mortality rates in Italy and Spain (Tobias 2020) and a 1.27 lowering of the R0 index in Italy (pre-lockdown 2.03, post-lockdown 0.76) (Guzzetta et al. 2021). With the advent of COVID-19 vaccines by December 2020, mass vaccination plans were launched in several countries (Haas et al. 2021). The vaccines became an essential tool to significantly reduce COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. Large-scale clinical trials and real-world data have shown that COVID-19 vaccines are safe, well tolerated, and highly effective in preventing COVID-19 infections, severe disease, hospitalizations, and deaths caused by the virus (Baden et al. 2021).

Treatment

Treatment protocols for COVID-19 infections varied throughout the pandemic as several variants of SARS-CoV-2 emerged. Initially, due to the lack of specific preventive and therapeutic measures, various pre-existing medications were used "off-label" for the treatment of patients infected with SARS-CoV2. Choice of drugs, possible combinations, dosages, and duration of treatment have been based on physician opinion and previous experience with similar conditions. The medications used combined antiviral activity, immunomodulatory action, and inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Oliver et al. 2022). However, the scientific evidence supporting the use of these has been limited.

Rehabilitation

As the pandemic progressed, reinfections and persisting cases gave rise to the challenge of the so-called long COVID or post-COVID syndrome and the psychological impact of the pandemic.

While most patients recovered within a few weeks after acute infection, evidence quickly emerged that some people reported persistence or development of various symptoms of varying intensity, regardless of the severity of their initial symptoms. The condition was named post-COVID syndrome, characterized by the continuation or development of new symptoms for at least 2 months after the initial infection. More than 17 million people in the WHO European Region may have experienced post-COVID syndrome during the first 2 years of the pandemic (WHO 2022).

Aims and objectives

This scoping review presents an overview of a large body of literature on the COVID-19 pandemic aimed at identifying and synthesizing evidence-based guidelines for the prevention, treatment, and long-term care related to COVID-19 in the European context using the examples of Italian, Spanish, German, and Dutch policies and experiences. Moreover, it identifies the psychosocial and educational lessons learnt during the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim is to provide an overview for the management of COVID-like situations in case of future pandemics. Recognizing European countries` errors and best practices is a promising step towards better management of future challenges.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted as part of the GLIDE-19 project, which is a collaboration of four different European institutions and funded by the European Union’s Erasmus+ program (2022-1-IT01-KA220-VET-000088032). Each partner of the GLIDE-19 consortium retrieved articles on one of the four main themes: prevention (Germany), treatment (Italy), long-term treatment/rehabilitation (Netherlands) and psychosocial impact (Spain) of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Search strategy

We searched the databases of PubMed, EBSCO (CINAHL, APA PsycINFO), and Cochrane using several combinations of keywords related to COVID-19 prevention, treatment, care, and rehabilitation. The combined searches resulted in 395 articles. The results were filtered for papers published in English, German, Italian, Spanish, and Dutch until 31 December 2022. After titles and abstracts screening, 138 papers were selected for full-text screening. Eighty-one articles were eligible for the scoping review. Gray literature (non-research evidence) on guidelines for COVID-19 prevention, treatment, care, and rehabilitation was retrieved from reports by WHO, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), and from each country’s respective institution for pandemic management. Reports from the Robert Koch Institute in Germany, the Italian and Spanish Ministries of Health, and the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) were screened in the gray literature analysis.

Study selection

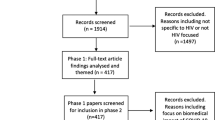

Studies that met the following criteria were included: (1) studies reporting at least one of the following types of information: best practices on prevention, care/treatment, or COVID-19 rehabilitation; (2) study designs: any existing literature (qualitative and quantitative studies)—in the case of too many results, the search was limited to reviews and meta-analyses up to 31 December 2022 and original research papers from 1 August 2022 to 31 December 2022; and (3) any type of population—in the case of too many papers, the search was narrowed down to healthcare professionals and social workers. For the study selection, see also Fig. 1.

Studies were excluded based on one or more of the following: (1) studies that did not include at least one European country; and (2) non-English (including Italian, Spanish, German, or Dutch articles).

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction for each article was performed using Microsoft Excel and included literature characteristics (e.g., journal, year of publication, title, authors), characteristics related to study method (e.g., article type, country where the study was conducted or included countries, healthcare setting), and key findings. As the data extraction process unfolded, we also enhanced the data extraction form, with new or more precise categories as needed. Reviewers had regular meetings to address any challenges and to ensure concordance with their abstraction methods. For data analysis, we descriptively summarized the data. The findings are presented in a narrative form.

Results

Prevention

This part focuses on prevention of COVID-19 infection. Based on research findings, control measures and best and worst practices in response to the COVID-19 pandemic are considered.

A paper by Bahl and colleagues (2022) showed that SARS-CoV-2 can be detected in the air and remains viable 3 hours after aerosolization. The transmission of COVID-19 is similar to SARS, which can spread through contact, droplets, and airborne routes. Airborne transmission is possible due to the presence of viral loads in the respiratory tract and the persistence of the virus in the air. They suggest precautions against airborne dispersal for the occupational health and safety of health workers treating patients with COVID-19 (Bahl et al. 2022).

A survey conducted online with over 2000 adults living in North America and Europe aimed to study the adherence rates and factors influencing compliance with social distancing recommendations during the early stages of the pandemic. The results showed that people’s adherence to these recommendations varied significantly among individuals and may depend on the specific actions they are being asked to take. The most effective factors that promoted adherence to social distancing guidelines include a desire to safeguard oneself, a sense of responsibility to protect the community, and the ability to work or study remotely. The most significant obstacles to compliance were having friends or family who required assistance and a need for social interaction to avoid feelings of isolation. To enhance adherence to social distancing measures, future interventions should combine personalized approaches aimed at overcoming the identified barriers with institutional measures and public health interventions (Coroiu et al. 2020).

Identifying secondary cases before the onset of infection by setting up quarantine and testing is a prevention measure that was heavily invested in during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic by developing digital contact tracing apps. However, the international experience of digital contact tracing apps during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how challenging their design and deployment are, including ethical issues such as data protection and privacy. In this field, there is potential for promising advancements through the integration of blockchain technology, ultra-wideband technology, and artificial intelligence in app design (O’Connell et al. 2021).

In vaccination campaigns, prioritization of certain population groups can influence the success of the campaign itself. A study which evaluated the vaccine allocation in Rhode Island and Massachusetts found that allocating a substantial proportion of vaccine supply to individuals at high risk of mortality is an effective strategy for reducing total cumulative deaths. The study suggests that a median of 327 to 340 deaths could be avoided in Rhode Island by optimizing vaccine allocation and vaccinating the elderly first. While the study focused on individuals over the age of 70, the results could be applied to other high-mortality groups (i.e., obesity, diabetes, past lung disease, lack of healthcare access) by allocating a higher proportion of vaccines to them. However, it is important to note that the study did not explicitly model other high-mortality groups, so the results would need to be interpreted with caution. In addition, individuals who have high-contact rates with high-mortality risk groups or cohabit with them should similarly be prioritized for vaccination. Though, vaccination of only high-contact groups cannot be considered as one of the best practices, mainly due to the wide mortality differences between the youngest and oldest age groups (Tran et al. 2021).

Treatment/care

Patients with a SARS-CoV-2 infection can experience a wide range of clinical manifestations, ranging from no symptoms to critical illness. Common symptoms include fatigue, fever, cough, loss of smell or tasting, and headache, among others. In addition, approximately 30% of patients also reported gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, nausea, and stomach pain (Struyf et al. 2022).

In general, adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection can be grouped into five severity categories (Struyf et al. 2022):

-

Asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic infection, positive test for SARS-CoV-2 but no symptoms consistent with COVID-19.

-

Mild illness, individuals who have any of the various signs and symptoms of COVID-19 (e.g., fever, cough, sore throat, malaise, headache, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of taste and smell) but do not have shortness of breath, dyspnea, or abnormal chest imaging.

-

Moderate illness, evidence of lower respiratory disease during clinical assessment or imaging and oxygen saturation ≥ 94% on room air at sea level.

-

Severe illness, previous listed symptoms, breathlessness, and increased respiratory rate which may indicate pneumonia and oxygen need.

-

Critical illness, individuals who have respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction requiring intensive support (Struyf et al. 2022).

It is important to differentiate between these conditions because they require different patient management. Therefore, there are three targets for current SARS-CoV-2 infection:

-

Asymptomatic or symptomatic infection of any severity.

-

Mild or moderate COVID-19 disease.

-

Severe or critical COVID-19 pneumonia (Struyf et al. 2022).

Bellino (2022) reported that most COVID-19 patients experience mild to moderate symptoms and can recover without needing special treatment. However, up to 15% of patients may develop severe or critical symptoms. Even though vaccination has significantly reduced the number of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths, managing severe cases remains a challenge due to the multisystemic nature of the infection, which can affect several body systems. This was especially true during the first stages of the pandemic, during which, due to the lack of specific preventive and therapeutic measures, various pre-existing medications were used "off-label" for the treatment of patients infected with SARS-CoV2. COVID-19 has been treated with antivirals, immunomodulators, antibiotics, stem cells, plasma therapy, and others (Oliver et al. 2022). Each of these treatment methods had benefits and drawbacks, and their effectiveness varied depending on the specific medication, the severity of the disease, and the stage of the illness. In summary, as reported in a review of Haddad and colleagues (Haddad et al. 2022), some antiviral agents, such as remdesivir, ivermectin, and lopinavir have shown some effectiveness in reducing the duration of hospitalization and improving clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19.

Corticosteroids usage, such as dexamethasone, is supported by robust evidence and has been shown to reduce mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients. However, the use of other medications, such as immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory drugs (Tocilizumab, sarilumab, Chloroquine) is quite conflicting. Moreover, conflicting data are present on the usage of convalescent plasma and vitamin D (Haddad et al. 2022). In Table 2, findings on other medications and their efficacy are reported. Subsequent randomized studies are needed to warrant the determination of their usefulness.

In addition, to explore the efficacy of existing drugs, scientists worldwide tried to develop new treatment options, such as new drugs, immunotherapies, and host-directed therapies.

These treatments can be divided into two main categories: those that directly target the virus replication cycle, and those that aim to boost the immune response or reduce inflammation (Jiang et al. 2022). Two main processes are thought to drive the pathogenesis of COVID-19. During the early stages of COVID-19, virus replication was the primary cause of the disease, and drugs such as antivirals were likely to be most effective. These work by preventing the virus from replicating and spreading throughout the body. As the disease progresses, however, the immune response can become dysregulated, leading to excessive inflammation and tissue damage. At this stage, treatments that focus on regulating the immune response or reducing inflammation may be more effective (Treatment Guidelines 2023).

In addition to the drugs discussed, and to the symptomatic treatment of most common clinical manifestations (antipyretics, analgesics, and antitussives for fever, headache, myalgias, and cough), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines (Treatment Guidelines 2023) suggest holistic patient care, based on the biopsychosocial model. It is so essential to encourage patients to drink fluids regularly to prevent dehydration and rest as needed during the acute phase of the illness. Patients can gradually increase their activity level based on their tolerance. Psychological support is an essential aspect of caring for COVID-19 patients. The pandemic has led to significant levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. Patients with COVID-19 may experience fear, isolation, and uncertainty, which can contribute to their overall psychological distress. Therefore, it is crucial to provide psychological support, as well as video-based therapy in case of lockdowns, to help patients cope with their illness and its associated challenges. Psychological support can include interventions such as counseling, psychotherapy, and cognitive–behavioral therapy, which can help patients manage their emotions, develop coping strategies, and improve their overall mental health. It is also important to provide patients with accurate and clear information about their illness, including its course, treatment options, and prognosis, to reduce anxiety and uncertainty (Karekla et al. 2021).

In conclusion, according to the review by Pandolfi and colleagues (Pandolfi et al. 2022), main aspects of the treatment policy for COVID-19 include the following:

-

1.

Significance of post-mortem investigations on COVID-19-caused deaths in developing effective treatment protocols in the early stages of the disease based on its etiopathogenesis.

-

2.

The early treatment of COVID-19 with common painkillers may not effectively address the illness and could even worsen SARS-CoV-2 symptoms in patients.

-

3.

Importance of having a comprehensive understanding of the demographic composition of each country to implement effective safety procedures for at-risk groups, such as the elderly.

-

4.

Decentralized medical coverage highly connected in large communities is better than centralized hospitals; in fact, better management of decentralized medical resources could have prevented a significant number of hospitalizations, thereby reducing the mortality rate.

-

5.

Sharing information, expertise, and skills between physicians and care personnel is crucial to speed up the development of a nationally agreed-upon and successful therapy protocol for COVID-19.

It is important to note that the best timing and combination of treatments for COVID-19 is still being studied, and treatment recommendations may vary depending on the severity of the disease.

Rehabilitation

Many patients with previous COVID-19 infection report persistent symptoms. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK elaborated three possible conditions after the infection (Pandolfi et al. 2022):

-

1.

Acute COVID-19, where signs and symptoms of the infection persist up to a maximum of 4 weeks

-

2.

Ongoing symptomatic COVID-19, where signs and symptoms of the infection last from 4 to 12 weeks

-

3.

Post-COVID-19 syndrome, in which signs and symptoms that develop during or after the infection are present even after 12 weeks and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis (NICE 2020)

Post-COVID symptoms are varied and can affect different organic systems. Therefore, the nature of these symptoms leads to the need of a holistic, tailored, and multidisciplinary rehabilitative intervention plan focused particularly on self-management (NICE 2020). The UK National Health Service (NHS) guidelines propose three models for the management of post-COVID patients according to the severity of the acute infection and on whether the patient has been hospitalized (NHS 2021):

-

1.

Non-hospitalized patients. A central role in this scenario is played by the general practitioner, who must be adequately trained on the topic of post-COVID rehabilitation to identify those symptoms that may have been caused by the infection and play a connection between patients and needed specialists.

-

2.

Patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19. These patients should undergo a 12-week post-discharge assessment, comprising chest X-ray and a review of symptoms for an eventual further continuation of the rehabilitation.

-

3.

Patients who required intensive care unit (ICU) admission. They should undergo a multidisciplinary reassessment at 4–6 weeks post-discharge. If conditions have improved, patients will be treated like other hospitalized individuals (NHS 2021).

WHO has identified the following conditions as the most important sequelae of COVID-19 that may require rehabilitation [Negrini et al. 2022; WHO 2022]:

-

Fatigue, exhaustion

-

Breathing impairment

-

Autonomic nervous system dysfunctions

-

Post-exertional symptom exacerbation (PESE)

-

Dysphagia and dysphonia

-

Arthralgia

-

Olfactory impairment

-

Cognitive impairment, such as attention deficit, memory impairment, concentration impairment, executive dysfunction, and cognitive communication disorder

-

Other psychological disorders: anxiety and depression

Staffolani and colleagues (2022), in their comprehensive narrative review of 2022, revised possible treatments for most of the common post-COVID manifestations. According to this review, for symptoms like pain and myalgia, symptomatic treatment may be used, while for patients with pulmonary or neurologic sequelae, chest physiotherapy and neurorehabilitation are useful. A multidisciplinary approach is recommended for respiratory symptoms, where non-pharmacological strategies such as breathing exercises, pulmonary rehabilitation, and postural relief may be helpful. Cardiovascular symptoms, such as tachycardia, may benefit from treatment with beta-blockers, while myocarditis usually resolves over time. For fatigue and cognitive and neuropsychiatric disorders, self-management, cognitive behavioral therapy, graded exercise treatment, and pacing may be used. Medications such as methylphenidate, donepezil, and modafinil may also be considered. Group therapy and supportive listening can also be effective. Sleep disturbances, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, and other mental health problems must be managed according to specific guidelines. Emerging treatments such as hyperbaric oxygen, breath exercise, and singing are being studied to treat respiratory symptoms of post-COVID. Other adjuvant therapies such as vitamin C, nicotinamide, probiotic supplements, leronlimab, tocilizumab, and melatonin are also being studied. Home-based and community rehabilitation can be delivered through different strategies, such as tele-rehabilitation or direct care (Lugo-Agudelo et al. 2021).

Social impact of pandemic and teaching methodologies to manage COVID-19 and prepare for future pandemics in Europe

The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is widely reported in the scientific literature. Already in 2020, Hossain and colleagues (Hossain et al. 2020) suggested that a psychiatric epidemic was co-occurring with the COVID-19 pandemic, which necessitates the attention of the global health community. People affected by COVID-19 may develop mental health problems, including depression, anxiety disorders, stress, panic attack, irrational anger, impulsivity, somatization disorder, sleep disorders, emotional disturbance, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and suicidal behavior (Hossain et al. 2020).

Regarding healthcare workers, the work overload, lack of resources, and uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have generated feelings of fear, exhaustion, anxiety, frustration, and sadness (Pinazo-Hernandis et al. 2022).

In relation to the differences between frontline personnel and the rest of the professionals, Western studies showed that the greatest psychological impact occurred in cases of direct contact with infected patients (Danet 2021).

According to a systematic review conducted by García-Iglesias and colleagues in 2020 (García-Iglesias 2020), which analyzed 13 studies from around the world, healthcare professionals working on the front line during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic experienced compromised mental well-being, with medium–high levels of anxiety, depression, nervousness, insomnia, and, to a lesser extent, stress. As noted by Lluch in 2022 (Lluch et al. 2022), burnout levels among healthcare professionals increased from medium–high to high during the pandemic, while compassion fatigue went from medium to high. These factors had a significant negative impact on the well-being and quality of life of healthcare professionals. The stress and anxiety experienced by professionals, in general, not only influences their health but also has an impact on the health system. Due to the emotional impact of COVID-19, it is advisable to offer psychological help to the professionals, ensuring not only their health but also the healthcare they offer (Santamaria et al. 2021).

Several sociodemographic variables including gender, profession, age, place of work, and department of work, and psychological variables such as poor social support and self-efficacy were associated with increased stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and insomnia in healthcare workers. There is increasing evidence that suggests that COVID-19 can be an independent risk factor for stress in these professionals (Spoorthy et al. 2020).

Yin and colleagues in their scoping review (Yin et al. 2022) highlight the importance of using quality improvement (QI) frameworks to guide response efforts during large-scale emergencies. QI is defined as "the use of deliberate and defined methods in continuous efforts to achieve measurable improvements in efficiency, effectiveness, performance, accountability, outcomes, and other quality indicators in services or processes" (Yin et al. 2022). The review identified 26 relevant records related to QI in emergency management during the COVID-19 pandemic. These cover five topics and, in order to fully reap the benefits of QI methodologies, focus on both the individual project level and the organizational level, with a seamless integration of these approaches into the overall management philosophy and culture of the organization: (1) collaborative problem solving and analysis with stakeholders; (2) supporting learning and capacity development in QI; (3) learning from past emergencies; (4) implementing QI methods during COVID-19; and (5) evaluating performance using frameworks/indicators.

Collaborative problem-solving and analysis with stakeholders emerged as the most common topic, highlighting the importance of stakeholder engagement in facilitating public health emergency response. The review also identified sixteen records related to learning and capacity building, with a focus on improving capacity among individuals involved in the public health response to COVID-19. The records discussed various QI methods, tools, and techniques to prepare participants for learning, including educational resources and training programs. Overall, the review concludes that improving access to educational resources and building capacity in QI may represent key actions (Yin et al. 2022).

Following Filip and colleagues (Filip et al. 2022), there is a need to restructure public healthcare systems to be better prepared for other diseases. Systems need to be reshaped for efficient and capable management around five measures: (1) management (limiting entry to healthcare facilities to ensure the safety of patients and professionals); (2) protection (developing protocols and measures to retain, protect, and support patients and staff); (3) containment through transmission control and suppression (redirecting non-urgent cases from hospitals to outpatient facilities); (4) information (facilitating and coordinating communication between different professionals); and (5) support (developing best-practice guidelines and legislation to coordinate global cooperative action) (Filip et al. 2022).

During the pandemic, there was a great need to train professionals to respond to the challenges faced and to acquire the necessary skills and knowledge.

Traditional training methods were adapted to the context of the pandemic, considering the mandatory safety distance and the demand for short and effective training. In this context, the Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda (Madrid, Spain) implemented a digital training strategy based on the production and publication of training pills through a mobile application (Revuelta-Zamorano et al. 2021). The design of the training pills was based on mobile learning and micro-learning teaching–learning methodologies as useful and effective tools to respond to the training needs of a university hospital in a health emergency. Mobile learning is an advanced method of digital learning in which content is accessed through wireless devices. It is a support for the continuity of education and training. Micro-learning is a variant of m-learning, which consists of the fragmentation of content into small units of digital information in a state of constantly updating those deals with a specific topic, in a short period of time (no more than 15 min). Both tools have received huge success among healthcare workers (Revuelta-Zamorano et al. 2021).

Discussion

In this scoping review, the impact of COVID-19 on the European and global population emerges in its full force, resulting in a significant number of deaths and numerous mid- and long-term sequelae on the entire population.

The pandemic has highlighted the critical importance of managing health-related emergency events across multiple levels, including initial response, information management, communication, and resource preparedness and distribution. The lessons learned from this experience should guide future emergency management. One of the crucial takeaways is the importance of cooperation and collaboration between health authorities, governments, and the public. Effective and transparent communication, guidelines, and proper preparation by healthcare professionals and government agencies are also essential to a successful response to future emergencies.

To accurately measure the impact of the pandemic on public health and investigate alternative policy options, it is crucial to have reliable death toll measurements. Reported deaths provide only a partial count of the total death toll, while excess mortality (i.e., the net difference between observed or estimated all-cause mortality during the pandemic and expected mortality based on past trends) provides a more accurate assessment of the pandemic’s total mortality impact. A study published in the Lancet (COVID-19 Excess Mortality Collaborators 2022) leveraged data from locations where all-cause mortality data were available from before and during the pandemic to estimate excess mortality at global and country level due to the pandemic. They also explored the statistical relationship between excess mortality rate and key covariates and population health-related metrics. The study found that by December 31, 2021, the estimated number of excess deaths due to COVID-19 was nearly three times greater than reported deaths. The magnitude of the excess mortality burden varied substantially between countries, with high excess mortality rates in eastern and central Europe, among others. Despite all GLIDE consortium partner countries reporting a higher population vaccination rate than the European average, and in particular Italy and Spain had a primary course vaccination rate of about 80%, they reported a higher number of deaths than Germany and the Netherlands. Overall, we have to say that the differences in the number of deaths reported in each of these countries are likely the result of a complex interplay between many different factors and cannot be fully explained by vaccination rates alone. While vaccination is a crucial tool in controlling the spread of COVID-19 and reducing the severity of the illness, it is not a guarantee of complete protection against the virus. Additionally, the effectiveness of vaccines may vary based on factors such as the specific variant of the virus (Shao et al. 2022) that is circulating and individual differences in immune response.

Some of the factors that can contribute to the different mortality rates between these countries are differences in the age distribution of the population, the prevalence of pre-existing health conditions, the quality of healthcare systems, the education of healthcare professionals and the psychological support provided to them, and the timing, clarity, and effectiveness of public health measures implemented to control the spread of the virus (Kerr et al. 2022). In vaccination campaigns, some of these factors need to be carefully considered; for example, it is crucial to balance the needs of high-mortality/high-risk groups with the need to protect essential workers and maintain essential services.

In addition to vaccines, preventive measures put in place to counter the rapid spread of the virus have not always had the desired effect, mainly due to poor public adherence (Coroiu et al. 2020; de Noronha et al. 2022). This can be attributed to, among other things, a lack of shared consensus at an international level (Abu El Kheir-Mataria et al. 2023). In fact, not all countries have adopted these measures in the same way and with the same timing. For example, at the beginning of the pandemic, some countries underestimated the importance of social distancing and the use of masks, while others implemented these measures only after the virus had already spread widely. In other cases, errors were related to lack of resources or difficulty in coordinating actions among different regions or countries. For example, some countries had difficulty providing personal protective equipment to health workers or ensuring equitable access to testing and treatment. In addition, there have been some critical issues inherent in the measures themselves, as was the case with the green pass and contact tracing apps (O’Connel et al. 2021; Campanozzi et al. 2022).

From what has been discussed, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that it is important for governments and national authorities to take timely and coordinated action. They should work together to communicate a unified scientific message and avoid fragmented responses. This will help to build trust between governments, citizens, and the scientific community. It is also important to develop effective strategies for communication and information dissemination through modern channels, such as social media platforms.

The COVID-19 pandemic has generated many conflicting opinions about available treatments due to the lack of specific information about the virus. As a result, many therapies were tried and tested empirically, with varying results. Some physicians followed their own experience and opinions rather than official guidelines, which may have been a result of the lack of clear and specific information, as well as the urgency to find life-saving solutions.

While scientific studies were accelerated to find effective treatments, to date, there is still no specific therapy approved for the treatment of COVID-19. This highlights the importance of a rigorous scientific approach in the research and development of new treatments. Developing specific treatments takes time and resources. COVID-19 experience has allowed for the recognition and understanding of this, and that prevention is always the best initial strategy in health emergencies.

In the future, focusing on prevention and relying on robust scientific processes to develop effective specific treatments will be essential. Additionally, it is important to recognize that without controlled clinical studies, it is not possible to establish the efficacy and safety of any treatment. Therefore, official guidelines based on rigorous scientific evidence are necessary to ensure that patients receive the best possible care.

To better equip individuals to protect themselves, their families, and their communities, in the first stages of a pandemic, it is therefore important to build knowledge-based capacity through early education and enabling environments. This can be achieved by integrating the scientific basis of infectious disease prevention and control, hygiene, and public health into primary and lifelong education programs, starting from an early age and promoting safe and healthy behaviors. Additionally, health authorities can engage the health workforce to provide accurate health communication during times of crisis and invest in modern communication channels and tools such as video, social media, and games to improve communication and education efforts (WHO 2022).

As extensively discussed in the results, COVID-19 infection as a multisystemic disease led to several long-term effects on various organs, requiring rehabilitation. Although to date it is not yet possible to know with certainty what the long-term effects of the pandemic will be, cognitive impairment following COVID-19 is being increasingly recognized as an acute and possibly long-term sequelae of the disease. The virus may directly enter the brain or contribute to neuroinflammation through systemic mechanisms such as a cytokine storm. COVID-19-related long-term olfactory dysfunction and early damage to olfactory and limbic brain regions suggest a pattern of degeneration like that seen in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Lewy body dementia (Kay 2022). Biomarkers of COVID-19-induced cognitive impairment are currently lacking, but there is some limited evidence that SARS-CoV-2 could preferentially target the frontal lobes, as suggested by behavioral and dysexecutive symptoms, frontotemporal hypoperfusion on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electroencephalography (EEG) slowing in frontal regions, and frontal hypometabolism (Toniolo et al. 2021). These data suggest a possible wave of post-COVID dementia in the coming decades, even if more research is needed to fully understand the mechanism and extent of this potential association. In addition, overall, the evidence suggests that COVID-19 can have a significant impact on mental health, with increased rates of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and sleep disturbances among those who have been infected (Hossain et al. 2020; Tu et al. 2021).

The presented evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has posed an intricate challenge for disaster management and healthcare professionals, with a much greater impact in terms of size, scope, and transmission compared to other disasters. The response to this crisis has been complex and has been hindered by a shortage of established models and prior experience, which has put significant strain on existing systems. Countries’ capacity to respond to the pandemic was uneven, with some countries having well-resourced and organized health systems, guaranteeing their populations acceptable levels of protection for life and health, while others had insufficient health coverage. The importance of having specialized and updated media and communication resources in the healthcare setting that allow and facilitate the training of professionals with respect to action protocols and clinical evidence with immediacy has become evident. In this regard, future work should be aimed at improving the resources for producing content and measuring its impact on healthcare practice.

Raising healthcare professionals and public awareness of mental health and its role before, during, and after a major epidemic or outbreak is essential. Developing community-based mental health initiatives and programs that focus on mental health training and education can be particularly effective. By prioritizing preventive mental health, we can improve overall well-being and resilience, ultimately contributing to more effective pandemic and epidemic preparedness. Particular attention should be given to post-traumatic stress disorder, which is a common consequence of all emergency events. Therefore, educating health professionals but also the population, providing psycho-education on the topic, is optimal in the perspective of possible new emergencies. Moreover, preventive mental health should become a key element to improve pandemic and epidemic preparedness. This can be achieved by strengthening the assessment of mental and psychological impact of public health and social measures prior to their implementation and establishing effective monitoring mechanisms (WHO 2022).

Limitations

Although this scoping review was conducted according to the suggested methodology, we acknowledge our study has some limitations. We restricted our search to only four databases and focused on papers in English from the EU, which might impact the comprehensiveness of our search results. This limitation could introduce bias related to societal and cultural aspects. Furthermore, given the ongoing presence of COVID infections in our population, the guidelines, as well as the scientific evidence related to rehabilitation and treatment, are continuously evolving. Consequently, this scoping review provides data that should be recognized as subject to updates.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented a significant challenge in the twenty-first century. Our global society is more interconnected than ever, and emerging pathogens do not respect geopolitical boundaries. This pandemic has illustrated that infectious diseases are complex and influenced by various interconnected factors, revealing weaknesses in our health, socioeconomic, environmental, and political systems. To effectively respond to pandemics like COVID-19 and prepare for future public health threats, proactive investment in public health infrastructure and capacity is crucial. It is also essential to continue improving international surveillance, cooperation, coordination, and communication. To better prepare for future infectious threats, we need to maximize investment in training and harness the potential of emerging technologies. By doing so, we can enhance our ability to respond to public health crises and improve outcomes. Simulation exercises on a city level can be considered to identify gaps in training, skills, and operations, while multilateral, multidisciplinary exercises and training programs can be developed to build future skill agendas. The xxxx project aims to support healthcare professionals in achieving enhanced skills and competencies to manage current and (possible future) pandemics by developing a multidimensional training program ( https://www.glide19.eu). In conclusion, we are called to shift our mindset and adopt new approaches different from what we are accustomed to.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Abu El Kheir-Mataria W, El-Fawal H, Chun S (2023) Global health governance performance during Covid-19, what needs to be changed? a Delphi survey study. Glob Health 19(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-023-00921-0

Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, Diemert D et al, COVE Study Group (2021) Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. New Engl J M 384(5): 403–416. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

Bahl P, Doolan C, de Silva C, Chughtai AA, Bourouiba L, MacIntyre CR (2022) Airborne or droplet precautions for health workers treating coronavirus disease 2019? J Infect Dis 225(9):1561–1568. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa189

Bellino S (2022) COVID-19 treatments approved in the European Union and clinical recommendations for the management of non-hospitalized and hospitalized patients. An Med 54(1):2856–2860. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2022.2133162

Campanozzi LL, Tambone V, Ciccozzi M (2022) A Lesson from the green pass experience in Italy: a narrative review. Vaccines 10(9):1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10091483

Choi H, Qi X, Yoon SH, Park SJ, Lee KH, Kim JY et al (2020) Extension of coronavirus disease 2019 on chest CT and implications for chest radiographic interpretation. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2(2):e200107. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryct.2020200107

Coroiu A, Moran C, Campbell T, Geller AC (2020) Barriers and facilitators of adherence to social distancing recommendations during COVID-19 among a large international sample of adults. PLoS ONE 15(10):e0239795. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239795

COVID-19 Excess Mortality Collaborators (2022) Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020-21. Lancet 399(10334): 1513–1536.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02796-3

COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel (2023) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. National Institutes of Health. Available at https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ Accessed on 20 June 2023

Danet A (2021) Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in Western frontline healthcare professionals. A systematic review. Impacto psicológico de la COVID-19 en profesionales sanitarios de primera línea en el ámbito occidental. Una revisión sistemática. Medicina Clinica 156(9): 449–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2020.11.009

De Noronha N, Moniz M, Gama A, Laires PA, Goes AR, Pedro AR, Dias S, Soares P, Nunes C (2022) Non-adherence to COVID-19 lockdown: who are they? A cross-sectional study in Portugal. Public Health 211:5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.07.001

Filip R, Gheorghita Puscaselu R, Anchidin-Norocel L, Dimian M, Savage WK (2022) Global Challenges to public health care systems during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review of pandemic measures and problems. JPM 12(8):1295

Gabutti G, d’Anchera E, De Motoli F, Savio M, Stefanati A (2021) The epidemiological characteristics of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe: focus on Italy. IJERPH 18(6):2942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062942

García-Iglesias JJ, Gómez-Salgado J, Martín-Pereira J, Fagundo-Rivera J, Ayuso-Murillo D, Martínez-Riera JR, Ruiz Frutos C (2020) Impacto del SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) en la salud mental de los profesionales sanitarios: una revisión sistemática. Rev Esp Salud Publica 94(1):e1–e20

Guzzetta G, Riccardo F, Marziano V, Poletti P, Trentini F, Bella A et al (2021) Impact of a nationwide lockdown on SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility. Italy EID 27(1):267–270. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2701.202114

Haas EJ, Angulo FJ, McLaughlin JM, Anis E, Singer SR, Khan F et al (2021) Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet 397(10287):1819–1829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00947-8

Haddad F, Dokmak G, Karaman R (2022) A comprehensive review on the efficacy of several pharmacologicagents for the treatment of COVID-19. Life 12(11):1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/life12111758

Hossain MM, Tasnim S, Sultana A, Faizah F, Mazumder H, Zou L, McKyer ELJ, Ahmed HU, Ma P (2020) Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Research 9: 636. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.24457.1

Imagining the future of pandemics and epidemics: a 2022 perspective (2022) Geneva: World Health Organization Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

Jiang Y, Zhao T, Zhou X, Xiang Y, Gutierrez-Castrellon P, Ma X (2022) Inflammatory pathways in COVID-19: Mechanism and therapeutic interventions. MedComm 3(3):e154. https://doi.org/10.1002/mco2.154

Karekla M, Höfer S, Plantade-Gipch A, Neto DD, Schjødt B, David D, Schütz C, Eleftheriou A, Pappová PK, Lowet K, McCracken L, Sargautytė R, Scharnhorst J, Hart J (2021) The role of psychologists in healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned and recommendations for the future. Europ J Psychol Open 80(1–2):5–17

Kay LM (2022) COVID-19 and olfactory dysfunction: a looming wave of dementia? J Neurophysiol 128(2):436–444. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00255.2022

Kerr S, Vasileiou E, Robertson C, Sheikh A (2022) COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 outcomes from Delta AY.4.2: cohort and test-negative study of 5.4 million individuals in Scotland. J Glob Health 12: 05025. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.12.05025

Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, Tang HJ, Hsueh PR (2020) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents 55(3):105924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924

Lluch C, Galiana L, Doménech P, Sansó N (2022) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction in healthcare personnel: a systematic review of the literature published during the first year of the pandemic. Healthcare 10(2):364. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020364

Lugo-Agudelo LH, Sarmiento K, Brunal, MAS, Correa, JCV, Borrero, AMP, Franco, LFM et al (2021) Adaptations for rehabilitation services during the covid-19 pandemic proposed by scientific organizations and rehabilitation professionals. J Rehab Med 53(9): jrm00228. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2865

Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, Hasell J, Macdonald B, Dattani S, Beltekian D, Ortiz-Ospina E, Roser M (2020) Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus' Accessed on 14 June 2023

National Health Service (2021) National guidance for post-COVID syndrome assessment clinics; Version 2

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2020) COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19

Negrini S, Kiekens C, Cordani C, Arienti C, De Groote W (2022) Cochrane "evidence relevant to" rehabilitation of people with post COVID-19 condition. What it is and how it has been mapped to inform the development of the World Health Organization recommendations. Eur J Phys Rehab Med 58(6):853–856. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.22.07793-0

O’Connell J, Abbas M, Beecham S, Buckley J, Chochlov M, Fitzgerald B (2021) Best practice guidance for digital contact tracing apps: a cross-disciplinary review of the literature. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 9(6):e27753. https://doi.org/10.2196/27753

Oliver JC, Silva EN, Soares LM, Scodeler GC, Santos AS, Corsetti PP, Prudêncio CR, de Almeida LA (2022) Different drug approaches to COVID-19 treatment worldwide: an update of new drugs and drugs repositioning to fight against the novel coronavirus. Therap Adv Vaccines Immunother 10:25151355221144844. https://doi.org/10.1177/25151355221144845

Pandolfi S, Valdenassi L, Bjørklund G, Chirumbolo S, Lysiuk R, Lenchyk L, Doşa MD, Fazio S (2022) COVID-19 medical and pharmacological management in the European countries compared to Italy: an overview. IJERPH 19(7):4262. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074262

Pinazo-Hernandis S, Galvañ Bas A, Dosil Diaz C, Pinazo-Clapés C, Nieto-Vieites A, Facal Mayo D (2022) El peor año de mi vida. Agotamiento emocional y burnout por la COVID-19 en profesionales de residencias. Estudio RESICOVID [The worst year of my life. Emotional exhaustion and burnout due to COVID-19 in nursing home professionals. RESICOVID study]. Revista Espanola de Geriatria y Gerontologia 57(4): 224–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2022.06.001

Revuelta-Zamorano M, Vargas-Núñez JA, de Andrés-Gimeno B, Escudero-Gómez C, Rull-Bravo PE, Sánchez-Herrero H (2021) Estrategias de formación durante la pandemia por covid-19 en un hospital universitario. Metas de Enfermería, 16–25

Santamaría MD, Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Rodríguez IR, Alboniga-Mayor JJ, Gorrotxategi MP (2021) Impacto psicológico de la COVID-19 en una muestra de profesionales sanitarios españoles. Revista De Psiquiatría y Salud Mental 14(2):106–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2020.05.004

Shao W, Chen X, Zheng C, Liu H, Wang G, Zhang B, Li Z, Zhang W (2022) Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in real-world: a literature review and meta-analysis. Emerg Microbes Infect 11(1):2383–2392. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2022.2122582

Spoorthy MS, Pratapa SK, Mahant S (2020) Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic-A review. Asian J Psychiatry 51:102119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119

Staffolani S, Iencinella V, Cimatti M, Tavio M (2022). Long COVID-19 syndrome as a fourth phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Le Infezioni in Medicina 30(1): 22–29. https://doi.org/10.53854/liim-3001-3

Struyf T, Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, Takwoingi Y, Davenport C, Leeflang MM, Spijker R, Hooft L, Emperador D, Domen J, Tans A, Janssens S, Wickramasinghe D, Lannoy V, Horn SRA, Van den Bruel A, Cochrane COVID-19 Diagnostic Test Accuracy Group (2022) Signs and symptoms to determine if a patient presenting in primary care or hospital outpatient settings has COVID-19. Cochrane Database System Rev 5(5):CD013665. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013665.pub3

Tobías A (2020) Evaluation of the lockdowns for the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Italy and Spain after one month follow up. Sci Total Environ 725:138539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138539

Toniolo S, Scarioni M, Di Lorenzo F, Hort J, Georges J, Tomic S, Nobili F, Frederiksen KS, Management Group of the EAN Dementia and Cognitive Disorders Scientific Panel (2021) Dementia and COVID-19, a bidirectional liaison: risk factors, biomarkers, and optimal health care. JAD 82(3): 883–898.https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-210335

Tran TN, Wikle NB, Albert E, Inam H, Strong E, Brinda K et al (2021) Optimal SARS-CoV-2 vaccine allocation using real-time attack-rate estimates in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. BMC Med 19(1):162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-02038-w

Tu Y, Zhang Y, Li Y, Zhao Q, Bi Y, Lu X, Kong Y, Wang L, Lu Z, Hu L (2021) Post-traumatic stress symptoms in COVID-19 survivors: a self-report and brain imaging follow-up study. Mol Psychiat 26(12):7475–7480. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01223-w

World Health Organization (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 46. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331443. Accessed on 17 September 2023

World Health Organization (2022) Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID). https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition. Accessed on 14 June 2023

World health organization (2022) Clinical management of Covid-19: living guideline, 15 september 2022. Geneva

World Health Organization (2023) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses. Accessed on 26 September 2023

World Health Organization Data (2023) WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/?mapFilter=cases. Accessed on 14 June 2023

Wu Z, McGoogan JM (2020) Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA 323(13):1239–1242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648

Yin XC, Pang M, Law MP, Guerra F, O’Sullivan T, Laxer RE, Schwartz B, Khan Y (2022) Rising through the pandemic: a scoping review of quality improvement in public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 22(1):248. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12631-0

Funding

This work is part of the project GLIDE-19 (https://www.glide19.eu/) which is funded by the Erasmus+ programme (no. 2022–1-IT01-KA220-VET-000088032).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the work. Literature search and content analysis was performed by all authors. V.F. and G.S. wrote the draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Formica, V., Piccinni, A., Saraff, G. et al. COVID-19 prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation: a scoping review of key concepts for future pandemic preparedness. J Public Health (Berl.) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-024-02298-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-024-02298-9