Abstract

Aim

To assess the reliability of the Colombian version of the Kidscreen-52 in school children and adolescents ages 8 to 18 in the city of Bucaramanga, Colombia.

Subject and methods

An evaluation of diagnostic technology was performed with 121 children and adolescents who completed the Colombian version of Kidscreen-52. The population was selected by cluster sampling in five public schools. Age, sex, socioeconomic condition, school grade, and the 10 dimensions of Kidscreen-52 were analyzed. The internal consistency of the responses was estimated via Cronbach’s alpha coefficient as a measure of the reliability of the Kidscreen scores; the test–retest reproducibility was evaluated calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient and the Bland–Altman limits of agreement method after the students completed the questionnaire twice.

Results

The mean age was 11.9 ± 2.5 years, and 67 (55.4%) were girls. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.61 to 0.89 and intraclass correlation coefficient from 0.70 to 0.90. The mean difference was close to zero (–4.5) with narrow limits of agreement (–27.0 to 18.1). The Colombian version of the Kidscreen-52 showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95).

Conclusion

The values for test–retest reproducibility were similar by sex, but the intraclass correlation coefficient was lower in the age 8 to 11 group compared to the age 12 to 18 group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defined quality of life as “the perception that an individual has of their position in life, in the context of the culture and value system in which they live in relation to their goals, expectations and concerns” (The WHOQOL Group 1995). This concept includes the health of the individuals, their psychological state, their degree of independence, their relationships with others and with the environment, and their religious or spiritual beliefs (Saxena et al. 1997). However, some authors suggest that it is more appropriate to refer to “Health-Related Quality of Life” (HRQoL) because its construct encompasses the WHO definition of health and includes the dimensions of social, physical and cognitive functioning, mobility, personal care, and emotional well-being (Guyatt et al. 1993; Karimi and Brazier 2016; Rajmil et al. 2001).

Thus, since 1990, numerous self-report instruments have been designed with the intention of measuring HRQoL in children and adolescents (Solans et al. 2008). These must satisfy certain criteria, such as being available in several languages, evaluating different health states, having been included in scientific studies and having adequate psychometric properties (Ravens-Sieberer et al. 2014b).

Among them is the Kidscreen-52, which was developed and applied simultaneously in 13 European countries (Ravens-Sieberer et al. 2005). This instrument has shown satisfactory internal consistency values (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.77 and 0.89) for the 10 dimensions. Likewise, test–retest reproducibility has been evidenced in an interval of 2 weeks, with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) between 0.56 and 0.77 (Ravens-Sieberer et al. 2008).

Despite these data, few studies have reported test–retest reproducibility (European Kidscreen Group 2006; Hong et al. 2007; Ng et al. 2015; Tebe et al. 2008). To date, there are no known publications that show information on the limits of agreement of Bland and Altman in the same participants, if one takes into account that this is a worldwide known method (Bland and Altman 1986). In this regard, several authors point out the importance of evaluating test–retest reproducibility because it indicates how robust the instrument is when applied under similar conditions (Aaronson et al. 2002; Janssens et al. 2015). Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the reliability of the Colombian version of the Kidscreen-52 in school children and adolescents in the city of Bucaramanga, Colombia.

Methods

Participants and sampling

This study followed the regulations established in Resolution No. 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Colombia and was classified as “risk-free research” (República de Colombia & Ministerio de Salud 1993). The Ethics Committee for Scientific Research of the Universidad Industrial de Santander approved this research according to the EPI2023 code.

A diagnostic technology evaluation study was conducted with students ages 8 to 18 linked to five public educational institutions in Bucaramanga, Colombia. Bucaramanga is located in northeastern Colombia, with a population of 581,130 inhabitants and was considered one of the cities with the best social indicators in the country (Aguilera 2014).

The calculation of the sample size of 118 students was obtained by taking into account a power of 80%, a significance level of 5%, and an ICC value of 0.70 (European Kidscreen Group 2006). Probabilistic cluster sampling of the educational institutions was performed, and then the sample was selected by random probability sampling from the class lists.

Children and adolescents from 8 to 18 years of age of both sexes were included. Sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, socioeconomic status, and school grade) and variables related to the Kidscreen-52 were analyzed.

Measures

The Kidscreen Group authorized the use of the Colombian version of Kidscreen-52 for this study. The questionnaire consists of 10 dimensions (physical well-being, psychological well-being, moods & emotions, self-perception, autonomy, financial resources, parent relation & home life, social support & peers, school environment, and social acceptance). The responses are based on a Likert scale of frequency and intensity with a time frame of one week. A high score indicates a better HRQoL (European Kidscreen Group 2006; Jaimes-Valencia et al. 2019). Additionally, the instrument contains a binary item on the presence of limitation, disease or permanent health problem with the options of Yes or No.

Data collection

Initially, the authorization of the educational institution was requested through the signing of the Institutional Informed Consent by the rector or coordinator. The class lists of the 3rd to 11th grades were obtained to make the random selection of the students who were then given information about the project and the informed consent to be completed by their parents or caregivers.

The application of the Kidscreen-52 was carried out during school hours in a quiet and comfortable place provided by the institution. Authorized students were told what the questionnaire consisted of, and their verbal assent was requested. During the application, doubts about certain questions or words were resolved. The completion time ranged from 10 to 20 minutes. The second application of the questionnaire was conducted after an interval of 2 to 3 weeks in the same place and at the time in which it had been completed for the first time.

The information was typed in duplicate and validated with Epidata 3.1 software; the database without errors was exported to Stata I/C version 14.0. The variables age and socioeconomic status were categorized (8 to 11 vs. 12 to 18 years and low vs. middle, respectively), and the 14 items of the Kidscreen-52 formulated in a negative way were recoded according to the indications of the Kidscreen Questionnaires Handbook (European Kidscreen Group 2006).

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and proportions were calculated for the qualitative variables, and measures of central tendency and dispersion were calculated for the quantitative variables. To determine the reliability, the applicability of the questionnaire was assessed through the evaluation of the floor and ceiling effect, which was considered acceptable with a value lower than 15% (Terwee et al. 2007). Subsequently, the internal consistency was estimated using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, the test–retest reproducibility was calculated with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC2.1) in a random effects model, and the functional limitation variable was evaluated with the Kappa coefficient of Cohen. The analysis was performed for each dimension and for the entire questionnaire. Values between 0.70 and 0.79 were interpreted as satisfactory, values between 0.80 and 0.89 were considered good, and values greater than or equal to 0.90 were considered excellent (Fayers and Machin 2016).

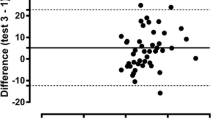

The Bland and Altman limits of agreement graphically represented the average of the differences between the first and second application of the Kidscreen-52. An average of the differences close to zero with narrow limits favored a good level of agreement (Bland and Altman 1986).

Results

Sixty-seven (55.4%) female students participated with an average age of 12.1 ± 2.4 years (95% CI 11.5–12.6); the average age of male students was 11.8 ± 2.6 years (95% CI 11.1–12.5). No statistically significant difference was found for age according to sex (p = 0.771). The description of the participants is shown in Table 1. When evaluating the applicability of the questionnaire, there were no maximum and minimum scores.

Internal consistency

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entire questionnaire was 0.95, which is considered excellent. Good coefficients were obtained (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.80 and 0.89) in six dimensions; in three, they were satisfactory (Cronbach’s alpha from 0.70 to 0.79), and the self-perception dimension presented a coefficient lower than 0.70 (Table 2).

Test–retest reproducibility

Excellent reproducibility was found for the entire questionnaire (ICC 0.91 95% CI 0.86–0.94). Satisfactory coefficients were obtained that ranged between 0.70 and 0.77 in five dimensions, and four were considered to have good reproducibility (0.80 to 0.87). It should be noted that parental relationship and home life dimension showed excellent reproducibility (ICC 0.90 95% CI 0.86–0.93) (Table 2).

When analyzing reproducibility for the entire questionnaire according to sex and age group, ICCs greater than 0.90 were found in men and women and in the age group of 12 to 18 years. When taking into account the 10 dimensions in both sexes, it was observed that the female sex recorded lower coefficients in the dimensions physical well-being (0.72) and social support & peers (0.71), while the male sex obtained lower coefficients in self-perception (0.70) and autonomy (0.68). On the other hand, the age group of 8 to 11 years had lower ICC in seven of the ten dimensions (Table 3).

With respect to the presence of functional limitation, good test–retest reproducibility was observed (κ 0.83 95% CI 0.67–0.93). However, when analyzed according to sex and age groups, excellent reproducibility was found for females (κ 0.92 95% CI 0.78–1.00) but was unsatisfactory for males (κ 0.68 95% CI 0.37–0.92). In the two age groups (8 to 11 and 12 to 18), reproducibility was good (κ 0.84 95% CI 0.63–0.06 and κ 0.80 95% CI 0.51–1.00, respectively).

Bland and Altman agreement limits

The average of the differences was –4.5 with a standard deviation of 11.5 and limits of agreement between –27.0 and 18.1. Figure 1 shows that the distribution of the scores did not present a defined pattern; there was a greater number of data from the 180 score, and five (4.1%) scores were not included in the limits of agreement, which indicates that the questionnaire has a good level of agreement. Likewise, there was a normal distribution of the average of the differences (p = 0.71).

With respect to the averages of the differences for each dimension, negative values close to zero with narrow limits of agreement were found. The autonomy dimension obtained a perfect average of the differences, while the physical well-being and moods & emotions dimensions were the only ones that registered values different from zero (–1.0 and –1.3, respectively). Table 4 shows narrow ranges in all dimensions, indicating a good level of agreement and precision in the estimates. In relation to sex and age group, negative values were found for the averages of the differences, being lower in males and in the age group of 12 to 18 years (Table 4).

Discussion

The internal consistency and test–retest reproducibility of the Colombian version of the Kidscreen-52 were excellent according to the criteria suggested by Fayers and Machin (Fayers and Machin 2016). Likewise, there was a good level of agreement when finding an average value of the differences close to zero with narrow limits (Bland and Altman 1986).

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.95 for the entire questionnaire, and the values for the 10 dimensions ranged between 0.61 and 0.89. Six dimensions had coefficients greater than 0.80, and only one (self-perception) had a value lower than 0.70. These findings are not surprising given that the Kidscreen-52 contains 52 items and it has been shown that the more items an instrument contains, the greater the Cronbach’s alpha since the length of the questionnaire positively influences the coefficient (Streiner et al. 2015; Tavakol and Dennick 2011).

Although few studies reported internal consistency values for the complete questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients greater than 0.90 were recorded. An example of this is the work of Hong et al. (2007) with 405 participants (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94), Parizi et al. (2014) with 328 students (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94) and Zhu et al. (2019) that included 4385 adolescents aged 11 to 17 years (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96).

Some studies show similar values of internal consistency, lower than 0.70 in the self-perception dimension. Jaimes-Valencia et al. (2019) found a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.59 when evaluating 146 students, and Parizi et al. (2014) and Stevanovic et al. (2013) observed Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.60 and 0.58, respectively (Jaimes-Valencia et al. 2019; Parizi et al. 2014; Stevanovic et al. 2013). It is possible that some words contained in the items of this dimension were not understood by the smallest participants who had a limited vocabulary. An example of this is the term “appearance,” which was contained in two of the five items and was a constant concern during the application of the questionnaire among the youngest participants in this study.

In relation to test–retest reproducibility, it was observed that the ICCs ranged between 0.70 (95% CI 0.58–0.78) in the social acceptance dimension and 0.90 (95% CI 0.86–0.93) in the parent relation & home life dimension. These findings are similar to those reported by Zhu et al., who found ICCs between 0.72 (social acceptance) and 0.84 (school environment); however, it is important to mention that this study included participants aged 11 to 17 years (Zhu et al. 2019).

Other studies have reported lower values, such as those observed by Ravens-Sieberer et al., who found ICCs between 0.56 and 0.77 when applying the questionnaire to 10% of the sample evaluated in 10 European countries with an interval of two weeks; three dimensions obtained ICCs of less than 0.60 (moods & emotions, autonomy and social acceptance) (Ravens-Sieberer et al. 2008). On the other hand, Tebe et al. observed that six of the ten dimensions presented values lower than 0.70, with the autonomy dimension being the one that obtained the lowest value (ICC 0.55) (Tebe et al. 2008).

The differences in the ICC values could be attributed to the time interval between the first and second application of the questionnaire, the subjectivity of the evaluated dimension, and the possibility that the instrument is “reactive,” that is, the participant has been sensitized by answering the questionnaire on the first occasion and had more time to think about their answers the second time (Streiner et al. 2015; Orozco 2010).

Fayers and Machin (2016) consider another factor that affects test–retest reproducibility, the characteristics of the participants, given that lower values have been obtained when participants are very young (Fayers and Machin 2016). In this study, children ages 8 to 11 obtained lower ICC in all dimensions with the exception of self-perception and social acceptance.

In relation to the results obtained by sex, it was found that girls and younger individuals had higher coefficients in the dimensions of self-perception and autonomy, while boys and younger participants obtained better ICC in the dimensions of physical well-being, social support & peers; the values in the other dimensions were similar. These findings could be because females are more likely to report worse physical well-being (OR 3.32 95% CI 2.12–5.21) that also varies over time due to the marked physical changes that occur during adolescence (Bisegger et al. 2005; Galarraga et al. 2009).

Although the item on the presence of functional limitation is specific to the Kidscreen, the publications do not mention its test–retest reproducibility. In this study, a good result was obtained (κ 0.83 95% CI 0.67–0.93), which would be expected because a permanent limitation does not change in a short time interval.

In relation to the level of agreement of Bland and Altman, an average of the differences close to zero was found with narrow limits of agreement that indicate a good level of agreement. If the range of the scores of the questionnaire is considered (52–260), the average of the differences represented 2.2% of this range, which could be considered negligible. In the literature, one study showed the limits of agreement to assess the concordance between parents and children and the magnitude of the possible discrepancies when using the Kidscreen-52 (Robitail et al. 2007). To our knowledge, there are no other published reports that use this methodology when applying this instrument to the same population on two different occasions.

The results obtained in this research were excellent when evaluating the internal consistency, test–retest reproducibility, and limits of agreement of Bland and Altman of the Colombian version of the Kidscreen-52. However, the limited literature on these psychometric properties of a questionnaire such as the Kidscreen-52 is striking, given that it is a widely known instrument that has been validated in various countries on all continents (Berra et al. 2013; Ng et al. 2015; Parizi et al. 2014; Ravens-Sieberer et al. 2014a; Zhu et al. 2019).

A limitation of this study could be the inclusion of students residing in a single city; however, the variability of the sample was ensured by obtaining a complete range of values as suggested by some authors (Berra et al. 2013; Tebe et al. 2008). In addition, the type of sampling allowed the inclusion of participants from different communes (areas of the city that group different neighborhoods). Although all students attended public educational institutions, this situation was to be expected given that only 12.5% of the students in the city attended private schools.

Having valid and reliable instruments designed for this population is a necessity if one takes into account the scarce evidence on Health-Related Quality of Life in Colombian children and adolescents. The Colombian version of the Kidscreen-52 presented excellent reliability when obtaining values higher than 0.90 for the internal consistency and for the test–retest reproducibility. Likewise, this version has a good level of agreement. These findings raise the possibility of applying this questionnaire in studies aimed at evaluating various types of interventions aimed at optimizing the quality of life of children and adolescents in school.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- HRQoL :

-

Health-Related Quality of Life

- WHO :

-

The World Health Organization

- ICC :

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

References

Aaronson N, Alonso J, Burnam A, Lohr KN, Patrick DL, Perrin E, Stein RE (2002) Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res 11:193–205. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015291021312

Aguilera M (2014) Bucaramanga: capital humano y crecimiento económico. In: L. A. Galvis (ed) Economía de las grandes ciudades en Colombia: Seis estudios de caso. Banco de la República de Colombia, p 55-107

Berra S, Tebe C, Esandi ME, Carignano C (2013) Reliability and validity of the KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in the 8 to 18 year-old Argentinean population. Arch Argent Pediatr 111:29–35. https://doi.org/10.5546/aap.2013.eng.29

Bisegger C, Cloetta B, von Rueden U, Abel T, Ravens-Sieberer U, European Kidscreen Group (2005) Health-related quality of life: gender differences in childhood and adolescence. Sozial- und Praventivmedizin 50:281–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-005-4094-2

Bland JM, Altman DG (1986) Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1:307–310

European Kidscreen Group (2006) The KIDSCREEN questionnaires: Quality of life questionnaires for children and adolescents. Pabst Science Publishers, Lengerich

Fayers PM, Machin D (2016) Quality of Life. The assessment, analysis and interpretation of patien-reported outcomes, 3rd edn. Wiley, Chichester

Galarraga RV, Aguila SL, Rajmil L (2009) Gender and self-perceived health in childhood and adolescence in Spain. Gac Sanit 23:433–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2009.01.014

Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL (1993) Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med 118:622–629. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009

Hong SD, Yang JW, Jang WS, Byun H, Lee MS, Kim HS, Oh MY, Kim JH (2007) The KIDSCREEN-52 quality of life measure for children and adolescents (KIDSCREEN-52-HRQOL): reliability and validity of the Korean version. J Korean Med Sci 22:446–452. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2007.22.3.446

Jaimes-Valencia ML, Perpina-Galvan J, Cabanero-Martinez MJ, Cabrero-Garcia J, Richart-Martinez M (2019) Adjusted linguistic validation and psychometric properties of the Colombian version of KIDSCREEN-52. J Child Health Care 23:20–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493518777291

Janssens A, Rogers M, Thompson Coon J, Allen K, Green C, Jenkinson C, Tennant A, Logan S, Morris C (2015) A systematic review of generic multidimensional patient-reported outcome measures for children, part II: evaluation of psychometric performance of English-language versions in a general population. Value Health 18:334–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2015.01.004

Karimi M, Brazier J (2016) Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics 34:645–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0389-9

Ng JY, Burnett A, Ha AS, Sum KW (2015) Psychometric properties of the Chinese (Cantonese) versions of the KIDSCREEN health-related quality of life questionnaire. Qual Life Res 24:2415–2421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-0973-z

Orozco LC (2010) Confiabilidad o de la consistencia, reproducibilidad, acuerdo y algo más. In: Medicion en salud: Diagnostico y evaluacion de resultados: Un manual critico mas alla de lo basico. Universidad Industrial de Santander, p 74-103

Parizi AS, Garmaroudi G, Fazel M, Omidvari S, Azin SA, Montazeri A, Jafarpour S (2014) Psychometric properties of KIDSCREEN health-related quality of life questionnaire in Iranian adolescents. Qual Life Res 23:2133–2138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0655-2

Rajmil L, Estrada MD, Herdman M, Serra-Sutton V, Alonso J (2001) Health related quality of life [HRQOL] in childhood and adolescence: a review of the literature and instruments adapted in Spain. Gac Sanit 15:34–43

Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Rajmil L, Erhart M, Bruil J, Duer W, Auquier P, Power M, Abel T, Czemy L, Mazur J, Czimbalmos A, Tountas Y, Hagquist C, Kilroe J, European Kidscreen Group (2005) KIDSCREEN-52 quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 5:353–364. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737167.5.3.353

Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Rajmil L, Erhart M, Bruil J, Power M, Duer W, Auquier P, Cloetta B, Czemy L, Mazur J, Czimbalmos A, Tountas Y, Hagquist C, Kilroe J, KIDSCREEN Group (2008) The KIDSCREEN-52 quality of life measure for children and adolescents: psychometric results from a cross-cultural survey in 13 European countries. Value Health 11:645–658. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00291.x

Ravens-Sieberer U, Herdman M, Devine J, Otto C, Bullinger M, Rose M, Klasen F (2014a) The European KIDSCREEN approach to measure quality of life and well-being in children: development, current application, and future advances. Qual Life Res 23:791–803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0428-3

Ravens-Sieberer U, Karow A, Barthel D, Klasen F (2014b) How to assess quality of life in child and adolescent psychiatry. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 16:147–158. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.2/usieberer

República de Colombia & Ministerio de Salud (1993) Resolución No. 08430 de 4 de octubre de 1993. Bogotá

Robitail S, Siméoni M-C, Ravens-Sieberer U, Bruil J, Auquier P, KIDSCREEN Group (2007) Children proxies' quality-of-life agreement depended on the country using the European KIDSCREEN-52 questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol 60:469–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.09.007

Saxena S, Orley J, WHOQOL Group (1997) Quality of life assessment: The World Health Organization perspective. Eur Psychiat 12(Suppl 3):263s–266s. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(97)89095-5

Solans M, Pane S, Estrada MD, Serra-Sutton V, Berra S, Herdman M, Alonso J, Rajmil L (2008) Health-related quality of life measurement in children and adolescents: a systematic review of generic and disease-specific instruments. Value Health 11:742–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00293.x

Stevanovic D, Tadic I, Novakovic T, Kisic-Tepavcevic D, Ravens-Sieberer U (2013) Evaluating the serbian version of the KIDSCREEN quality-of-life questionnaires: reliability, validity, and agreement between children’s and parents’ ratings. Qual Life Res 22:1729–1737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0286-4

Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J (2015) Selecting the items. In: Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J (eds) Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use, 5th edn. Oxford University Press, pp 76–99

Tavakol M, Dennick R (2011) Making sense of cronbach's alpha. Int J Med Educ 2:53–55. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

Tebe C, Berra S, Herdman M, Aymerich M, Alonso J, Rajmil L (2008) Reliability and validity of the Spanish version of the KIDSCREEN-52 for child and adolescent population. Med Clin (Barc) 130:650–654. https://doi.org/10.1157/13120999

Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR, van der Windt DAWM, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 60:34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

The WHOQOL Group (1995) The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med 41:1403–1409. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k

Zhu Y, Li J, Hu S, Li X, Wu D, Teng S (2019) Psychometric properties of the mandarin Chinese version of the KIDSCREEN-52 health-related quality of life questionnaire in adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Qual Life Res 28:1669–1683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02158-0

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Colombia Consortium. This study was partially supported by a Grant from Universidad Santo Tomás (XI Convocatoria Interna Acta 154 de 2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Martha J. Rodríguez: contributed to the planification of the study, collected the data, digited the information, performed the analysis, co-wrote and reviewed this manuscript.

Diana M. Camargo: contributed to the conceptualization of the study, co-wrote and reviewed this manuscript.

Luis C. Orozco: conceived and designed the analysis, performed the analysis, co-wrote and reviewed this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The Ethics Committee for Scientific Research of the Universidad Industrial de Santander approved this research according to the EPI2023 code.

Consent to participate

Informed written consent was obtained from the parents or guardians, and the child/adolescent gave his or her assent to be included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez, M.J., Camargo, D.M. & Orozco, L.C. Reliability of the Colombian version of the Kidscreen-52 for a child and adolescent student population. J Public Health (Berl.) (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-02058-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-02058-1