Abstract

Purpose

Because of the growing emphasis on place-based interventions to improve health, we sought to identify commonly measured, resident-reported neighborhood characteristics for use in evaluation studies.

Methods

A review was conducted of resident-reported neighborhood indicators in 27 published PubMed articles and eight non-academic gray literature sources. Neighborhood domains and items were evaluated across the literature to identify patterns in resident reporting on neighborhoods.

Results

A diverse range of survey items across reviewed literature comprised the following broad domains: physical conditions, social conditions, community resources, social agency, and neighborhood dynamics. Academic and gray literature varied in their assessments’ focus and the populations considered, with gray literature exploring a wider array of persons, such as those with disability, and positive aspects of neighborhoods. In general, there was a lack of a cohesive framework for measuring neighborhood well-being and no clear agreement on appropriate language and key definitions. Measures relevant to the elderly were largely absent from the US literature.

Conclusions

Most published articles on neighborhood measurement were derived from the criminology and sociology literature on the origins of violence and poverty. Their measures reflected this negative orientation. Gray literature included a broader perspective on neighborhoods and consideration of alternative populations such as the elderly and people with disability. This review’s identification of common metrics in neighborhood domains paves the way for building consolidated and standardized neighborhood measurement tools that will also fill current gaps in the literature, such as those concerning elderly residents or those with disabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The ways in which neighborhood characteristics influence health outcomes, daily functioning, and quality of life have drawn attention from fields of public health research and policy. Neighborhood characteristics have been associated with a wide range of health outcomes, including behavioral health (Hosokawa and Katsura 2020), sleep quality (Johnson et al. 2016; Troxel et al. 2020), preterm births (Giurgescu et al. 2017), obesity (Tamayo et al. 2016; Hoenink et al. 2019), tobacco dependence (Reitzel et al. 2012), and limited life spans (General OotS 2021). Given these associations, it is unsurprising that the US Department of Health and Human Services included “neighborhood and built environment” as one of the five defined domains of social determinants of health (“Social Determinants of Health” n.d.), underscoring the role of neighborhoods in health outcomes.

Tools that capture residential measurements are important for engaging residents and stakeholders while assessing the effectiveness of community development initiatives. The history of community development and renewal in the United States can be traced back to reform movements during the Progressive Era (Hoffman 2012) and continues into today. Initially, such efforts failed to include community input, but that has slowly changed. Collaborative partnerships with community groups create multifaceted teams guided by both bottom-up and top-down approaches. These partnerships have taken place in urban, suburban, and rural communities, in the United States and abroad (Savage et al. 2018; Freudenberg and Golub 1987; Liss-Levinson et al. 2020). A review of the strategies utilized by these partnerships yields mixed results in their ability to improve population health outcomes, community behaviors, public policy, or community environments (Roussos and Fawcett 2000). Despite supportive evidence of community change prompted by these partnerships, the degree of change has been called into question due to a lack of clear standards for measuring neighborhood quality of life or change (Roussos and Fawcett 2000).

Efforts have been made to identify and define neighborhood measurements while differentiating temporary from permanent features (Ndjila et al. 2019) to better determine how neighborhoods may affect resident health and the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving these neighborhoods. Neighborhood measurement methods include in-person evaluation, administrative data (e.g., police records), census data, and review of video recordings (Sampson and Raudenbush 2004). Other examples include the presence of alcohol and tobacco stores, commercial building security, crime data, and neighborhood walk scores (Sampson and Raudenbush 2004; Diez Roux et al. 2017). However, measurements such as resident perceptions of neighborhood characteristics hold predictive power that administrative or built environment measurements cannot capture. For example, perceived neighborhood characteristics have been reported as more accurately predicting physical activity than built environment assessments (Orstad et al. 2017).

As the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and health becomes clearer, it is increasingly important that collaborative partnerships and healthcare organizations are equipped with standardized, comprehensive tools for assessing changes in community development. This is especially true when large investments are made from multiple sectors with expectations for demonstrated improvement.

Resident-reported measures of neighborhood characteristics come from two primary sources. First, academic publications include a variety of surveys employed, especially from criminology and sociology literature. Naturally, these publications include an assessment of numerous characteristics of neighborhoods that are associated with violence and crime. Separate from the published literature are evaluation tools designed for neighborhoods and neighborhood interventions by third party organizations and governmental groups engaged in community development. These latter sources have produced neighborhood measurement tools to assist community development programs and published them in what is called “gray literature” (19-27 Stiefel et al. 2020; “User’s Guide for the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study Public Data” 2018, Mulcahy et al. 2020; Mulcahy 2017; “The Healthy Housing Outcomes Survey” 2019; “National Survey of Children’s Health Questionnaire” 2020; “CHIS Questionnaires” 2021; “Secondary Student Community Health In-School and Hybrid Only Module” 2020; “2021 State and Local Youth Risk Behavior Survey” 2021). This review aimed to assess the state of both academic and gray literature, while identifying resident-reported measures of neighborhoods currently being utilized and reported in the domestic and international literature to consider domains of coverage, populations included in the assessments, and characterizations of neighborhoods.

Methods

Search strategy and criteria selection

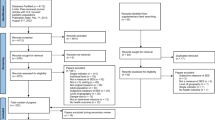

A scoping literature review was conducted on resident self-reported measurements of neighborhoods to identify commonly assessed neighborhood characteristics and the items chosen to represent them in the academic and gray literature, the latter of which is defined as publications outside of traditional academic scholarships, including reports, keynote addresses, briefs, and similar. A PubMed search of the Major MeSH term “Self-Report” AND “neighborhood disorder” yielded 28 results in the academic literature. A second PubMed search was conducted with the Boolean search terms “neighborhood disorder,” “neighborhood safety,” “neighborhood poverty,” “neighborhood cohesion,” and “self-report” and yielded 408 results. Filters applied in both searches isolated full-text English language articles published between 2010 and 2021. The results of these two searches underwent a title and abstract screening, in which any paper that indicated having self-reported neighborhood conditions as a variable was included for a full manuscript review. Throughout the screening, reference sections of the articles became a source for finding additional publications to increase the breadth and depth of the findings. Once the review reached a point at which the researchers observed that trends in neighborhood measures were apparent, and questionnaire items ceased to yield new information or additional insights (suggesting that a point of saturation had been reached), the review was concluded. At the conclusion of the screening, 27 published articles were included in the review (Table 1).

An advanced search using Google Scholar was conducted to identify gray literature sources for neighborhood measurements. This search was conducted using the Boolean terms “self-report,” “self-assessed,” “self-rated,” “self-estimated,” to search for papers that contained “neighborhood” in relation to health, safety, community, poverty, or disorder. Gray literature meeting inclusion criteria comprised surveys published in English since 2010 and those items evaluating resident self-reported measurement of one or more neighborhood characteristics through a primary source. While reviewing gray literature data sets, surveys, and websites, additional resources surfaced that were then evaluated for inclusion. The review of gray literature sources continued until the neighborhood domains assessed and their qualifying items became redundant. At the conclusion of the gray literature review, surveys developed by eight different organizations were included (Table 2).

Data extraction and organization

Information regarding self-reported neighborhood measures in published studies was extracted and compiled to identify trends in measured domains and items (Table 1). These items included the country and setting in which the study took place; method of self-reported data collection; characteristics these measurements assessed; and the validated scales used or modified in the resident survey. Although the majority of surveys were implemented in respondent residential areas, Kim et al. (2019) and Giurgescu et al. (2017) administered surveys at urban hospitals; therefore, gathering information potentially representative of many different neighborhoods simultaneously. These studies were categorized as urban, despite the possibility that a portion of the participants resided in rural and suburban areas.

Self-administered methods of data collection included online or paper surveys completed by respondents. Paper surveys were mailed out or dispersed at local centers. Interviews were conducted in-person, over the phone, or online. During review, if a survey item did not name the domain it was intended to capture, the item was assigned to a descriptive term commonly seen in the literature. After reviewing survey items within each category individually, recategorization and relabeling occurred when necessary to allow for comparison across all collected literature.

Details regarding the gray literature survey respondents and questionnaires were extracted and organized for comparison purposes (Table 2). The domain of neighborhood characteristics assessed in each gray literature source was recorded. Nomenclature from the source itself was reported, when possible, to define the measured neighborhood qualities. When necessary, the authors applied appropriate terminology used across the literature to review self-report questionnaire items that did not explicitly identify their measurement.

Categorization methodology and rationale

After extracting all items and questions available in the selected sources, categories of the most common domains measured were developed from terminology available in the literature (Table 3). These domains were further stratified into subcategories. For example, items comprising the domain “physical conditions” were organized and counted as either “physical order” or “physical disorder.” If items and survey questions described the same characteristic but under a different name, they were organized into the same subcategory and domain pairing. If a literature source provided questions without explicitly stating the aspect of neighborhoods they intended to measure, appropriate descriptive terms seen in other literature were assigned to them in the “characteristics assessed” column.

The several sources that noted what domains were measured, but did not directly provide all survey items, were still added to the “instances” count. Depending on the survey phrasing, the same item could be arguably used to support different neighborhood domains. For example, items concerning violence could be categorized as reflecting violence if asking about its presence as a neighborhood problem (Troxel et al. 2020), safety if asking about its absence (Palumbo et al. 2019), crime if inquiring after the frequency of criminal occurrences (Tamayo et al. 2016), fear of crime if reporting residential fear of being attacked, raped, or robbed (Giurgescu et al. 2017; Prado et al. 2017; Loh et al. 2019), or more broadly social disorder (Ndjila et al. 2019). Each item was evaluated to determine which aspects were most specifically addressed to ensure proper item placement. For concision, redundant or differently phrased items were grouped together or omitted from tables. For example, “attractive sites” and “interesting things to look at” both can be combined into “interesting and attractive things to look at” to qualify the term “neighborhood aesthetics. Overall, a comparison between academic and gray sources indicated that gray literature includes more survey items for diverse populations, such as elderly and disabled communities, and more positive attributes of neighborhood conditions.

Results

Following the search and screening process, 28 papers and eight gray literature sources were included in this review. Survey items from 22 published papers and one gray literature source were derived from previously reported or validated scales (Appendix Table 4). Surveys reported in the collected literature could be grouped into one of the following five domains: physical conditions, social conditions, community resources, social agency, and neighborhood dynamics. Domain items suggesting laudatory or positive connotations were placed in a separate subcategory from items capturing a similar neighborhood characteristic with negative connotations.

Of the 29 instances of physical condition measures, 18 measured aspects of physical disorder, while 11 measured aspects of physical order. Social conditions were evaluated by the number of studies asking questions regarding safety (20), social cohesion (16), social support (16), social trust (13), crime (13), violence (12), social disorder (12), engagement with community activities (6), fear (5), social disconnectedness (4), and social order (4). There were 21 instances of community resources measurements that were observed and broken down further into subcategories of amenities (12) and community services (10) available in the neighborhood. Social agency was measured most often at an organizational level as civic engagement (6) or more interpersonally as social control (5). Neighborhood dynamics were assessed by measures of community stability (7) and community development (3). Examples of items used to qualify subcategories are listed in Table 3 to demonstrate the range observed in the literature.

Differences between literature published in the United States and internationally were evident in both the populations of focus and the framing of neighborhood characteristics. Additionally, gray literature sources and academic literature differed in terms of target populations and content of survey tools. These differences suggest implications for practice and require further consideration to improve the measurement of neighborhoods.

Discussion

This study examined articles and gray literature that used resident-reported measures to understand neighborhood characteristics. Although international self-reports’ survey items distinguished them from domestic ones, these differences may be explained by demographic, economic, and cultural differences. To date, this appears to be the first review of resident-reported neighborhood measures inclusive of surveys from the gray literature.

Characteristics of neighborhood self-report toolkits in international literature

Academic studies conducted outside of the United States were closer to gray literature publications in two ways. First, they often included more information on diverse age groups, such as the elderly. Second, they often assessed neighborhood characteristics with a more positive connotation. Investigating the neighborhood friendliness suitability for the elderly sets international publications apart from American articles. Two international studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries measured neighborhood friendliness toward elderly and disabled communities (Shagdarsuren et al. 2017) or focused on adults over the age of 65 (Hsueh et al. 2016). Of all the US sources, Success Measures, a source from the gray literature, was the only one to measure neighborhood characteristics specifically for the elderly (Mulcahy et al. 2020; Mulcahy 2017). Older adults may be the most affected by disparate neighborhood characteristics as their mobility declines and dependence on their social network increases. Negative neighborhood characteristics have been associated with hastened cognitive decline and functional limitations (“Today’s Research on Aging” 2017).

Survey items that were most often characterized in negative terms in the US literature were often presented positively in the international literature. For example, Hosokawa and Katsura (2020) developed Likert scale survey items regarding physical conditions and safety to reflect positive aspects of the neighborhood. This is in contrast to many US studies that orient questions to be about the presence of disorder or crime. Shagdarsuren et al. presented positive statements of physical order and safety featuring both manmade and environmental characteristics, including the quality and cleanliness of the soil, air, river water, drinking water, and nature (Shagdarsuren et al. 2017).

Characteristics of neighborhood self-report toolkits in gray and academic literature

Patterns in survey content, format, and target population became apparent when analyzing survey items reported in gray and peer-reviewed literature. The peer-reviewed literature placed a greater emphasis on certain measurements, most notably physical disorder (14/18), physical order (9/11), social disorder (10/12), fear of crime (4/4), crime (11/13), and violence (8/12). Meanwhile, gray literature placed a greater emphasis on civic engagement (4/6) and community stability (5/7). While the majority of published surveys contained categorical scales, some gray literature included free response portions to better solicit resident perspectives. Additionally, gray literature sources were more child- and family-oriented in their target audience and survey content. Some surveys captured child neighborhood perceptions with direct survey administration (“CHIS Questionnaires” 2021; “Secondary Student Community Health In-School” 2020; “2021 State and Local Youth Risk Behavior Survey” 2021)), while others targeted parents to respond on behalf of their child (“National Survey of Children’s Health Questionnaire” 2020; “CHIS Questionnaires” 2021).

Gray literature measured similar neighborhood domains to those in the academic literature, contributing to a greater number of overall items measured. Although only two gray literature sources contributed to the six instances of measurement of neighborhood engagement with community activities, they accounted for 13 of the 18 measurement items (Mulcahy et al. 2020;“National Survey of Children’s Health Questionnaire” 2020). Four of the six sources measuring civic engagement were from gray literature (Stiefel et al. 2019; Mulcahy et al. 2020; Mulcahy 2017; “CHIS Questionnaires” 2021; “Secondary Student Community Health In-School” 2020). Notably, only one gray literature collection (Mulcahy et al. 2020; Mulcahy 2017) inquired about disability accessibility features and another about eco-friendly outdoor features (Mulcahy et al. 2020).

Terminological variability in residential self-reports

Although both academic and gray literature include similar aspects of resident reports on neighborhoods, there is little consistency in the language used to describe these aspects across the literature. Even when there is agreement in the terminology for the domain and subcategory being measured, the illustrating items vary greatly. In cases where the items substantively agree, varying specificity or cultural differences led to a breadth of survey items. For example, although some studies listed “trash” to support physical disorder (Hosokawa and Katsura 2020; Johnson et al. 2016; Troxel et al. 2020; Palumbo et al. 2019), others listed “litter,” (Johnson et al. 2016; ;“National Survey of Children’s Health Questionnaire” 2020; Matthews et al. 2019) “garbage,” (“User’s Guide for the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing” 2018) “rubbish” (Matthews et al. 2019) or specific forms of trash such as “broken bottles” in addition to “trash” or in place of it.

Our results are similar to those previously reported by Ndjila et al. who found linguistic variability and diversity in the peer-reviewed literature’s survey items supporting synonyms of physical and social conditions (Ndjila et al. 2019). Not only are many synonyms used, but the same items are interpreted as evidence for different neighborhood characteristics. While Palumbo et al. (2019) categorized “using/selling drugs” and “drug dealers have the most money” as physical disorder, other studies cited the use and selling of drugs as an example of social disorder (Giurgescu et al. 2017; Pruitt et al. 2012; Hastings and Snowden 2019) or more generally as a neighborhood problem. (“Secondary Student Community Health In-School and Hybrid Only Module” 2020). It is of course unsurprising that a qualitative domain such as neighborhood perceptions, which has arisen organically over time, would lack conceptual clarity. Bringing clarity to the terms of this reporting is an important task ahead.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. As discussed previously, the dissimilarity of items and language in literature created difficulty in evaluating and organizing characteristics and items (Table 3). Nonetheless, though this is a limitation, it might also be considered a finding given this study’s parameters and aims. Although a consistent strategy was applied in sorting items, it relied heavily on interpretation. Many measures used Likert scales, which may lead to an underestimation of attention paid to positive or negative aspects of neighborhoods. International studies translated either questionnaires or study findings, which may imprecisely convey the characteristics that the researchers in those settings attempted to measure.

Conclusions & recommendations

Items in resident self-report surveys were organized into the following domains: physical conditions, social conditions, community resources, social agency, and neighborhood dynamics. Within these domains, there is great variability in terminology and items used to evaluate neighborhoods. This review highlights the need for future research to develop a systematic approach for characterizing and categorizing resident neighborhood perceptions. Few studies define geographical boundaries or inquired as to how long respondents had resided in their neighborhoods, limiting the strength and reliability of gathered information to inform community development practices.

There remains a need to generate items that intentionally include currently overlooked and vulnerable residents in communities, such as older adults and those with disabilities. In addition, clear definitions, standardized scales, and the consolidation of items representing the domains presented in this review would lead to better appraisal of community development efforts, more generalizable results, and easier comparisons of related work.

References

Arcaya MC, Schnake-Mahl A, Binet A, Simpson S, Church MS, Gavin V, Coleman B, Levine S, Nielsen A, Carroll L, Ursprung S, Wood B, Reeves H, Keppard B, Sportiche N, Partirdge J, Figueora J, Frakt A, Alfonzo M, Abreu D, … Youmans T (2018) Community change and resident needs: designing a participatory action research study in Metropolitan Boston. Health Place 52:221–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.05.014

Abramson D, Stehling-Ariza T, Gareld R, Redlener I (2008) Prevalence and predictors of mental health distress Post-Katrina: findings from the Gulf Coast child and family health study. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2(2):77–86

Cerin E, Suen YN, Barnett A, Huang WYJ, Mellecker RR (2017) Validity of a scale of neighbourhood informal social control relevant to pre-schoolers’ physical activity: A cross-sectional study. SSM - Population Health 3:57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.11.007

CHIS Questionnaires (2021) UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/design/Pages/questionnairesEnglish.aspx. Accessed 2/7/2023

Chola L, Alaba O (2013) Association of neighbourhood and individual social capital, neighbourhood economic deprivation and self-rated health in South Africa–a multi-level analysis. PloS one 8(7):e71085. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071085

Coulton CJ, Korbin JE, Su M (1996) Measuring neighborhood context for young children in an urban area. Am J Commun Psychol 24:5–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02511881

Dawson CT, Wu W, Fennie KP, Ibañez G, Cano MÁ, Pettit JW, Trepka MJ (2019) Perceived neighborhood social cohesion moderates the relationship between neighborhood structural disadvantage and adolescent depressive symptoms. Health Place 56:88–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.01.001

Diez Roux A, Moore K, Melly S, Wang X, Joshi R (2017). Neighborhood health and poverty in Philadelphia. Urban collaborative data brief number 2. Dornsife School of Public Health, Drexel University. https://drexel.edu/uhc/resources/briefs/Neighborhood-Poverty/. Accessed 2/7/2023

Donnelly L (2015) Neighborhood disadvantage and school dropout: a multilevel analysis of mediating contexts (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from RUcore: Rutgers University Community Repository. https://doi.org/10.7282/T37S7QRD

Elder GH, Eccles JS, Ardelt M, Lord S (1995) Inner-city parents under economic pressure: perspectives on the strategies of parenting. J Marriage Fam 57(3):771–784. https://doi.org/10.2307/353931

Freudenberg N, Golub M (1987) Health education, public policy and disease prevention: a case history of the New York City Coalition to End Lead Poisoning. Health Educ Q 14:387–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818701400402

General OotS (2021) Community Health and Economic Prosperity Engaging Businesses as Stewards and Stakeholders— A Report of the Surgeon General

Giurgescu C, Zenk SN, Templin TN, Engeland CG, Kavanaugh K, Misra DP (2017) The Impact of neighborhood conditions and psychological distress on preterm birth in African-American women. Public Health Nurs 34:256–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12305

Grow HM, Saelens BE, Kerr J, Durant NH, Norman GJ, Sallis JF (2008) Where are youthactive? Roles of proximity, active transport, and built environment. Med Sci Sports Exerc 40:2071–2079

Hastings JF, Snowden LR (2019) African Americans and Caribbean Blacks: Perceived neighborhood disadvantage and depression. J Commun Psychol 47(2):227–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22117

Hoenink JC, Lakerveld J, Rutter H, Compernolle S, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Bárdos H et al (2019) The moderating role of social neighbourhood factors in the association between features of the physical neighbourhood environment and weight status. Obes Facts 12:14–24. https://doi.org/10.1159/000496118

Hosokawa R, Katsura T (2020) The relationship between neighborhood environment and child mental health in Japanese Elementary School students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155491

Hsueh MC, Liao Y, Chang SH (2016) Perceived neighborhood and home environmental factors associated with television viewing among Taiwanese older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13070708

Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Estrada-Martinez L, Zenk Viruell-Fuentes E, Villarruel AM, Stokes C (2006) Engaging urban residents in assessing neighborhood environments and their implications for health. J Urban Health 83(3):523–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-006-9053-6

Jack E, McCormack GR (2014) The associations between objectively determined and self-reported urban form characteristics and neighborhood-based walking in adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 11(1):71. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-11-71

Joe L, Carlson JA, Sallis JF (2008) Active Where? Individual item reliability statistics adolescent survey. http://www.drjamessallis.sdsu.edu/Documents/AW_item_reliability_Adolescent.pdf. https://activelivingresearch.org/sites/activelivingresearch.org/files/AW_item_reliability_Adolescent.pdf

Johnson DA, Lisabeth L, Hickson D, Johnson-Lawrence V, Samdarshi T, Taylor H et al (2016) The social patterning of sleep in African Americans: associations of socioeconomic position and neighborhood characteristics with sleep in the Jackson Heart Study. Sleep 39:1749–1759. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.6106

Kim Y, Lee S, Jung H, Jaime J, Cubbin C (2019) Is neighborhood poverty harmful to every child? Neighborhood poverty, family poverty, and behavioral problems among young children. J Community Psychol 47:594–610. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22140

Liss-Levinson R, Young G, Goddeeris L (2020) Successful collaborations between local government and public health: exploring multisector partnerships to improve population health. https://debeaumont.org/resources/successful-collaborations-between-local-government-and-public-health-exploring-multisector-partnerships-to-improve-population-health/

Litwak E, Messeri P, Wolfe S, Gorman S, Silverstein M, Guilarte M (1989) Organizational theory, social supports, and mortality rates: a theoretical convergence. Am Sociol Rev 54(1):49–66

Loh VHY, Veitch J, Salmon J, Cerin E, Thornton L, Mavoa S et al (2019) Built environment and physical activity among adolescents: the moderating effects of neighborhood safety and social support. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 16:132. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0898-y

Martinez ML (2000) Neighborhood context and the development of African American children. Garland, New York, NY

Martinez LM, Black M, Starr RH (2002) Factorial structure of the Perceived Neighborhood Scale (PNS): A test of longitudinal invariance. J Community Psychol 30(1):23–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.1048

Matthews T, Odgers CL, Danese A, Fisher HL, Newbury JB, Caspi A et al (2019) Loneliness and neighborhood characteristics: a multi-informant, nationally representative study of young adults. Psychol Sci. 30:765–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619836102

Messeri P, Silverstein M, Litwak E (1993) Choosing optimal support groups: a review and reformulation. J Health Soc Behav 34(2):122–137. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137239

Meyer OL, Castro-Schilo L, Aguilar-Gaxiola S (2014) Determinants of mental health and self-rated health: a model of socioeconomic status neighborhood safety and physical activity. Am J Public Health 104(9):1734–1741. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302003

Mulcahy J (2017) Measuring Health Outcomes: Success Measures Evaluation Tools for Community Development and Health. Success Measures, NeighborWorks America

Mulcahy J, Kopf N, Johnson C, Schaffer Bacon B, Shibata A, Dahab D (2020) Success measures creative community development evaluation tools. https://successmeasures.org/artsandculturetools. Accessed 2/7/2023

National Survey of Children’s Health Questionnaire – Children Ages 12-17 (2020) Data Resource Center for Child & Adolescent Health. https://www.childhealthdata.org/learn-about-the-nsch/survey-instruments. Accessed 2/7/2023

Ndjila S, Lovasi GS, Fry D, Friche AA (2019) Measuring Neighborhood Order and Disorder: a Rapid Literature Review. Curr Environ Health Rep. 6:316–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-019-00259-z

Orban E, Sutcliffe R, Dragano N, Jöckel KH, Moebus S (2017) Residential surrounding greenness, self-rated health and interrelations with aspects of neighborhood environment and social relations. J Urban Health 94(2):158–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-016-0112-3

Orstad SL, McDonough MH, Stapleton S, Altincekic C, Troped PJ (2017) A systematic review of agreement between perceived and objective neighborhood. Environ Measures Assoc Phys Activ Outcomes 49(8). https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916516670982

Palumbo AJ, Wiebe DJ, Kassam-Adams N, Richmond TS (2019) Neighborhood environment and health of injured urban Black men. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 6:1068–1077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00609-5

Parker KE, Salmon J, Villanueva K et al (2019) Ecological correlates of activity-related behavior typologies among adolescents. BMC Public Health 19:1041. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7386-9

Prado CV, Rech CR, Hino AAF, Reis RS (2017) Perception of neighborhood safety and screen time in adolescents from Curitiba, Brazil. Rev Bras Epidemiol 20:688–701. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-5497201700040011

Pruitt SL, Jeffe DB, Yan Y, Schootman M (2012) Reliability of perceived neighbourhood conditions and the effects of measurement error on self-rated health across urban and rural neighbourhoods. J Epidemiol Commun Health 66:342–351. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2009.103325

Reitzel LR, Vidrine JI, Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Cao Y, Mazas CA et al (2012) Neighborhood perceptions are associated with tobacco dependence among African American smokers. Nicotine Tob Res 14:786–793. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr285

Rosenberg D, Ding D, Sallis JF, Kerr J, Norman GJ, Durant N, Harris SK, Saelens BE (2009) Neighborhood environment walkability scale for youth (NEWS-Y): reliability and relationship physical activity. Prev Med 49(2–3):213–8

Roussos ST, Fawcett SB (2000) A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annu Rev Public Health 21:369–402. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369

Sallis JF, Kerr J, Carlson JA, Norman GJ, Saelens BE, Durant N, Ainsworth BE (2010) Evaluating a brief self-report measure of neighborhood environments for physical activity research and surveillance: physical activity neighborhood environment scale (PANES). J Phys Act Health 7(4):533–540. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.7.4.533

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW (2004) Seeing Disorder: Neighborhood Stigma and the Social Construction of “Broken Windows”; 67(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250406700401

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277:918–924

Savage A, Brune S, Hovis M, Spencer SE, Dinan M, Seekamp E (2018) Working together: a guide to collaboration in rural revitalization. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/working-together-a-guide-to-collaboration-in-rural-revitalization. Accessed 2/7/2023

Schulz AJ, Zenk SN, Israel BA, Mentz G, Stokes C, Galea S (2008) Do neighborhood economic characteristics, racial composition, and residential stability predict perceptions of stress associated with the physical and social environment? findings from a multilevel analysis in Detroit. J Urban Health 85:642–661

Schulz AJ, Mentz G, Lachance L, Zenk SN, Johnson J, Stokes C, Mandell R (2013) Do observed or perceived characteristics of the neighborhood environment mediate associations between neighborhood poverty and cumulative biological risk? Health Place 24:147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.09.005

Secondary Student Community Health In-School and Hybrid Only Module (2020) CalSCHLS. https://calschls.org/survey-administration/downloads/. Accessed 8 June 2023

Secretti T, Nunes MAA, Schmidt MI, Stein MC, Santos SM (2019) Characteristics of neighborhood environment (social cohesion and safety) and common mental disorders in ELSA-Brasil study: a multilevel analysis. Cadernos de saude publica 35(1):e00197017. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00197017

Shagdarsuren T, Nakamura K, McCay L (2017) Association between perceived neighborhood environment and health of middle-aged women living in rapidly changing urban Mongolia. Environ Health Prev Med 22:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-017-0659-y

Social Determinants of Health (n.d.). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health. Accessed 2/7/2023

State and Local Youth Risk Behavior Survey for High Schoolers (2021). Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/questionnaires.htm. Accessed 2/7/2023

Stiefel MC, McNeely E, Riley CL, Roy B, Straszewski T, VanderWeele T (2020) Well-being assessment (adult-24 items). Institute for Healthcare Improvement

Suen YN, Cerin E, Mellecker RR (2014) Development and reliability of a scale of physical activity-related informal social control for parents of Chinese pre-schoolers. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 11:87. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-014-0087-y

Suen YN, Cerin E, Wua SL (2015a) Parental practices encouraging and discouraging physical activity in Hong Kong Chinese preschoolers. J Phys Act Health 12(3):361–369. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.203-0123

Suen YN, Cerin E, Huang WYJ, Mellecker RR (2015b) Measures of environmental correlates of physical activity for urban chinese preschool-aged children: development and reliability. SAGE Open 5(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015604690

Tamayo A, Karter AJ, Mujahid MS, Warton EM, Moffet HH, Adler N et al (2016) Associations of perceived neighborhood safety and crime with cardiometabolic risk factors among a population with type 2 diabetes. Health Place 39:116–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.03.007

The Healthy Housing Outcomes Survey (2019) Enterprise Community Partners and Success Measures. https://www.greencommunitiesonline.org/integrative-design. Accessed 2/7/2023

Today’s Research on Aging (2017) Population Reference Bureau. https://www.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/TRA20Alzheimers20and20Dementia.pdf. Accessed 2/7/2023

Troxel WM, Haas A, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Holliday SB, Richardson AS, Schwartz H et al (2020) Broken windows, broken Zzs: poor housing and neighborhood conditions are associated with objective measures of sleep health. J Urban Health 97:230–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00418-5

User’s Guide for the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study Public Data, Year 3 (2018) The Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Well-being

Von Hoffman A (2012) The past, present, and future of community development in the United States. In: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and the Low Income Investment Fund. Investing in what works for America’s communities. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/jchs.harvard.edu/files/w12-6_von_hoffman.pdf

Witherspoon D, Schotland M, Way N, Hughes D (2009) Connecting the dots: how connectedness to multiple contexts influences the psychological and academic adjustment of urban youth. Appl Dev Sci 13(4):199–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888690903288755

Acknowledgements

Author 1 gratefully acknowledges the support of the author’s work by the L. B. Research and Education Foundation.

Funding

There is no financial interest to report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anna L. Farrell, Ashley R. Banks, Daniel Skinner, and Kelly J. Kelleher made substantial contributions to the conception of this work and interpretation of data. Anna L. Farrell and Ashley R. Banks were involved with the drafting and revising of it critically for important intellectual content, approving the submitted version for publication. Each listed author agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in, having ensured that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved. All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Farrell, A.L., Banks, A.R., Skinner, D. et al. Resident-reported measurements of neighborhood characteristics: a scoping review. J Public Health (Berl.) (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-01954-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-01954-w