Abstract

Aim

This study examined the relationships between stress, excessive drinking, including binge and heavy drinking, and health insurance status among a regionally representative sample of adults living in Northern Larimer County, Colorado, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Subject and methods

Data from 551 adults aged 18 to 64 years (62.98% aged 45 to 65 years; 73.22% female; 92.98% non-Hispanic White) were used. The sample was weighted by age and binary sex. A series of logistic regressions were applied to examine bivariate associations among stress, drinking, and health insurance status, with and without accounting for the effects of sociodemographic and health-related covariates. Stratified analyses were applied to explore differential associations of stress and drinking among individuals with different health insurance coverage.

Results

A total of 23.23% of the adult sample reported binge drinking, and 16.15% reported heavy drinking; 10.53% of the sample reported both binge and heavy drinking. Individuals with higher levels of stress were more likely to report binge drinking (OR: 1.65; 95% CI: 1.65, 1.68) and heavy drinking (OR: 2.61; 95% CI: 2.54, 2.67), after adjusting for sociodemographic and health-related covariates. Relative to individuals with private health insurance coverage, adults enrolled in Medicaid and those without health insurance coverage were more susceptible to the effect of stress on binge and heavy drinking.

Conclusion

Our results highlighted a need for continuing statewide and/or national efforts in closing the insurance coverage gap and providing affordable marketplace health insurance in the hope of preventing excessive drinking due to high levels of stress during a challenging time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study was set in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, an unprecedentedly stressful health-related life event since its outbreak in late 2019. The sudden, unexpected, and prolonged pandemic has caused stress and evoked negative emotions among different populations worldwide, significantly disrupting life for all walks of life at the individual and societal levels (Dubey et al. 2020). Excessive alcohol consumption is one of the maladaptive coping strategies for stress (Horton 1943; Tamers et al. 2014; Turner and Wheaton 1997) and is a behavioral pathway through which individuals’ health is compromised (Cohen et al. 2016; Rahe et al. 1964). In a time when access to alcohol was limited due to social distancing, this study sought to examine the associations of stress and excessive alcohol consumption during the pandemic. In addition, we explored whether and to what extent the associations of stress and drinking would differ between individuals who had or lacked health insurance coverage during this challenging time.

Binge drinking is defined as consuming five or more drinks on one 2-hour occasion for men and four or more drinks for women. Heavy drinking, on the other hand, is determined by the amount of drinking per day or week. More than four drinks per day or 14 drinks per week for men, or three or more drinks per day or more than seven drinks per week for women is considered heavy drinking (National Institutes on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 2020). The consequences of excessive alcohol are costly and life-threatening. In 2010, the nation estimated spending 249 billion dollars solely on alcohol (Sacks et al. 2015). Binge and heavy drinking are also responsible for an increase in chronic health diseases (e.g., high blood pressure, stroke, cancer, weakened immune system) and mental health problems (World Health Organization 2018). Immediate health and safety concerns as a result of excessive drinking were also well-documented, including violence (Greenfield 1998), poisoning (Kanny et al. 2015), and motor vehicle crashes (Smith et al. 1999). On average, excessive drinking has caused 140,000 more deaths per year, shortening lives by 26 years in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2022).

Unfortunately, excessive alcohol consumption remained prevalent during the pandemic. In a recent report, one in six US adults reported binge drinking, consuming on average more than eight drinks per occasion (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2022). Researchers found that one in five US adults had been drinking more alcohol since the pandemic than they were a year ago (Tran et al. 2020). The trend was also found in Australia (Neill et al. 2020) and the UK (Kim et al. 2020), raising notable public health concerns worldwide. In addition, these researchers found that being a heavier drinker pre-pandemic, being a middle-aged adult, having average or higher income, suffering from a current job loss, and having worse self-reported mental health were among the risk factors for an increased amount of drinking during the pandemic (Tran et al. 2020; Neill et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2020). In other words, except for being higher income, the socially disadvantaged were more likely to report excessive alcohol consumption and suffer from the consequences of it (Collins 2016). Among individuals of lower socioeconomic status (SES), those who were under higher levels of stress were particularly more susceptible to binge and heavy drinking (Wells et al. 2002).

The US health system is a mix of public and private, for-profit and nonprofit insurers and health care providers. In addition to employment-based private insurance for eligible working-age adults, the federal government provides various programs for qualified people, such as Medicare for adults aged 65 and older and Medicaid for lower-income and unemployed adults aged 18 to 64 (Davis et al. 2014). In general, the research found that access to health insurance, regardless of whether private or public, increases individuals' access to health care, consequently improving health-related outcomes (Sommers et al. 2017). Despite numerous efforts invested in closing the health insurance gaps, nearly half (43%) of working-age adults have had spotty health insurance coverage since the pandemic (Commins 2020).

Although access to quality health care with insurance coverage greatly impacts health outcomes, its impact on alcohol consumption has been mixed in the literature. There are at least two competing hypotheses. On the one hand, loss of health insurance coverage makes access to health care unaffordable, with dauntingly high deductibles and out-of-pocket costs for those in need of health care, which in turn triggers excessive alcohol consumption in response to mounting stress (Horton 1943). Loss of health insurance during the pandemic, in particular, could exacerbate the stress that the pandemic has already brought about in everyday life, for instance, making the hard choice of whether to pay the rent, buy food, or seek health care (Dave and Kaestner 2009; Ward and Martinez 2015). On the other hand, the ex ante moral hazard phenomenon suggests that health insurance coverage, especially public insurance (e.g., Medicaid), may decrease individuals' effort and sense of responsibility to maintain their health (Dave and Kaestner 2009). Therefore, ex ante moral hazard becomes a plausible mechanism whereby having insurance coverage could increase the likelihood of excessive alcohol consumption. In either of the two scenarios, evidence suggests that individuals would vary in their likelihood of reporting excessive alcohol consumption, depending on whether and which health insurance coverage they had access to.

To this end, more evidence is needed as to the direction and the strength of the associations between stress and excessive alcohol consumption among insured and uninsured adults, as well as between insured adults with public (e.g., Medicaid) and private health insurance coverage, after controlling for the effects of covariates. Investigating the effect of health insurance status is also of practical importance in this context, as health insurance coverage is a modifiable risk factor for detrimental health consequences of stress and excessive alcohol consumption.

The present study

This study investigated the associations between stress and excessive alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated demographic characteristics. We hypothesized a positive association between stress and excessive alcohol consumption patterns (Hypothesis 1). That is, higher stress levels would be associated with a higher likelihood of engaging in excessive alcohol consumption. We further expected that the associations would vary between insured and uninsured adults after controlling for an array of covariates. Specifically, uninsured adults under higher stress levels would be more likely to engage in excessive alcohol consumption than adults with private health insurance coverage (Hypothesis 2a). Furthermore, relative to privately insured adults, adults with public insurance would also be more susceptible to the detrimental effects of stress in terms of drinking behaviors (Hypothesis 2b).

Methods

Data

The 2020 COVID-19 Supplemental Survey of the Northern Larimer County Community dataset was used in the present study. The Health Survey 2020 is a follow-up survey of households that had previously participated in the 2019 Health Survey. The Health Districts’ 2019 Community Health Survey was distributed to about 12,000 households in Larimer County that were contacted by mail. The survey was available in both English and Spanish. A total of 2532 surveys were returned, resulting in a response rate of 21%. Among 2463 households invited to participate in the 2020 follow-up survey, 1463 (59.40%) responses were received. The sample was weighted by age and gender using the 2020 estimated Larimer County population from the Colorado State Demography office to closely represent the adult residents. With weights, the results would be more generalizable to adult residents of Larimer County. Of 1463 participants, we excluded data from participants who did not provide information on age (n = 19) and adults aged 65 and older (n = 669). For the purpose of the data analysis and interpretation, we excluded data from participants who self-identified as nondrinkers (n = 192). We also excluded data from the participants with missing values in the main variables of interest (i.e., excessive alcohol consumption patterns and health insurance). Thus, the data analyzed in the present study were from a total of 551 individuals aged 18 to 64 years. Please see Fig. 1 for information on the data selection process.

Measures

The main exposure was stress experienced over the past month. The outcome variable was excessive alcohol consumption, including binge drinking and heavy drinking, in accordance with the NIAAA definition (National Institutes on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 2020), and no insurance coverage. Potential confounders/covariates were selected from the review of the literature and included the following variables: age, binary gender (woman or man), race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White or Hispanic and non-White), income (<185% federal poverty level [FPL], 186–250% FPL, 250–400% FPL, or >400% FPL), education attainment (up to 12 years, 13 to 16 years, or 17+ years), employment (full-time, part-time, unemployed, retired, and other), and self-rated health. Finally, the stress in the past 6 months due to COVID-19 was included for exploring and controlling for its effects on predicting the likelihood of excessive drinking as a result of increased levels of stress.

Analysis procedures

A three-step analysis was undertaken to investigate the three research hypotheses. The first analysis was descriptive and categorized participants by demographics, SES, self-rated health, insurance type, and stress level as an entire group and by excessive alcohol consumption patterns. Frequency (column %) was reported and analyzed with chi-square tests for any significant differences among non-excessive alcohol drinkers and excessive alcohol drinkers with weights (Table 1). A p-value evaluated the difference between insured and uninsured adults at the level of α = .05. The secondary analysis was bivariate associations of stress and excessive alcohol consumption while also taking into account the effects of the covariates. The exposure in our model was stress level (none or minimum stress, moderate level of stress, or high level of stress), and the outcomes were binge drinking (0 = no, 1 = yes) and heavy drinking (0 = no, 1 = yes). In addition to the significance test (i.e., the p-value), a 95% confidence interval of the estimates (i.e., odds ratios) was reported for the effect size. The third analysis involved the health insurance status as the effect modifier. The associations between stress and excessive alcohol consumption were further stratified by private health insurance, public health insurance (i.e., Medicaid), and uninsured status. All analyses were conducted with SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Descriptive characteristics

The final sample consisted of 511 participants aged 18 to 64 years. Among them, 73.22% were women, 68.18% had income >400% FPL, 92.82% were non-Hispanic White, 6.25% had an education level below 12 years, 63.93% were full-time employees, 10.56% were retired, and 97.27% reported good to excellent health. The sample, on average, reported 15.11 out of 30 in terms of COVID-19-related stress and anxiety in the past month. Regarding the main variables of interest, the participants reported 3.06 out of 4 in terms of stress levels. In addition, 23.23% reported binge drinking and 16.15% reported heavy drinking. Among them, 10.53% reported both binge and heavy drinking. Finally, 89.84% had private health insurance coverage, 6.35% had public health insurance coverage (i.e., Medicaid), and 3.81% had no insurance coverage (Table 1).

With weights, the probability of reporting binge drinking varied across age group (χ2 (2) = 7451.03, p < .001), binary gender (χ2 (1) = 513.80, p < .001), race and ethnicity (χ2 (1) = 5555.43, p < .001), education attainment (χ2 (2) = 1601.57, p < .001), employment (χ2 (4) = 4608.72, p < .001), income (χ2 (3) = 1356.61, p < .001), self-rated health (χ2 (3) = 465.83, p < .001), and health insurance status (χ2 (2) = 605.44, p < .001). Binge drinkers reported significantly higher levels of stress than those who were not engaged in binge drinking, t(549) = −3.36, p < .001. The probability of reporting heavy drinking also varied across age group (χ2 (2) = 133.89, p < .001), binary gender (χ2 (1) = 415.43, p < .001), race and ethnicity (χ2 (1) = 2425.48, p < .001), education attainment (χ2 (2) = 373.31, p < .001), employment (χ2 (4) = 2942.38, p < .001), income (χ2 (3) = 1462.67, p < .001), self-rated health (χ2 (3) =1753.88, p < .001), and health insurance status (χ2 (2) = 178.67, p < .001). Heavy drinkers reported significantly higher levels of stress than those who were not engaged in heavy drinking, t(549) = −4.8, p < .001.

Regression analyses of stress on excessive drinking patterns

Tables 2 and 3 present the results of models that regressed excessive drinking patterns on stress. For binge drinking, a one-unit increase in stress was associated with a 65% increase in the odds of reporting binge drinking (odds ratio [OR] = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.62–1.68, p < .001). (Model 1; Table 2). Model 2, adjusted for covariates, showed that the positive association between stress and binge drinking held (OR = 2.26, 95% CI: 2.20–2.33, p < .001). In addition, each additional unit increase in COVID-19-related stress and anxiety was associated with a 7% decrease in the odds of reporting binge drinking (OR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.92–0.93, p < .001). For heavy drinking, a one-unit increase in stress was associated with a 1.61% increase in the odds of reporting heavy drinking (OR = 2.61, 95% CI: 2.54–2.67, p < .001; Model 1; Table 3). Model 2, which was adjusted for covariates, showed that the positive association between stress and heavy drinking also held (OR = 1.85, 95% CI: 1.79–1.92, p < .001). In addition, each additional unit increase in COVID-19-related stress and anxiety was associated with a 1% decrease in the odds of reporting binge drinking (OR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.985–0.998, p = .01).

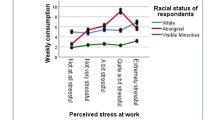

Effect of stress on binge drinking by health insurance status

Model 3 (Table 2) was estimated with the interaction terms for stress levels and three health insurance statuses to examine whether the association between stress and drinking would vary across health insurance groups. For binge drinking, the interaction of stress and health insurance status was significant, χ2(6) = 1919.37, p < .001. Astonishingly, each additional unit increase in stress was associated with a 12,821% increase in likelihood of reporting binge drinking among adults with Medicaid (OR = 129.21, 95% CI: 104.97–159.05, p < .001) and a 437% increase in the likelihood of reporting binge drinking among adults with no health insurance coverage (OR = 5.37, 95% CI: 4.71–6.12, p < .001), relative to the reference group of adults with private health insurance coverage. In other words, adults having public health insurance or lacking health insurance coverage were particularly likely to report binge drinking under stress relative to the reference group of adults with private health insurance coverage.

Effect of stress on heavy drinking by health insurance status

Model 2 (Table 3) was estimated with the interaction terms for stress and three health insurance statuses. The interaction terms of stress levels and health insurance group were significant, χ2(2) = 786.92, p < .001, suggesting that the effect of stress on heavy drinking would be contingent upon the level of health insurance. Each additional unit increase in stress was association with a 418% increase in likelihood of reporting heavy drinking among adults with Medicaid (OR = 5.18, 95% CI: 3.73–7.21, p < .001) and a 2334% increase in the likelihood of reporting binge drinking among adults with no health insurance coverage (OR = 23.34, 95% CI: 19.31–28.21, p < .001). In other words, adults having public health insurance or lacking health insurance coverage were particularly likely to report heavy drinking under stress relative to the reference group of adults with private health insurance coverage.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine whether the rates of excessive or binge drinking would persist with the change in alcohol sales regulations for retail liquor stores, bars, and restaurants in response to COVID-19. Furthermore, we examined to what extent the strength of the associations between stress and excessive alcohol consumption would be contingent on health insurance coverage. All the models were controlled for contextual and health-related factors such as demographic, socioeconomic, and self-reported health, as well as stress specific to COVID-19.

Our results showed that the rate of binge drinking was lower in our sample (23.23%) compared to a rate of 34.1% reported in 2020 with a convenience sample (Grossman et al. 2020). Selectivity bias may play a role here, as individuals who engage in binge drinking may be less likely to participate in a survey study. The rate of heavy drinking in our sample (16.15%) was similar to the recent public report in 2022 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2022). The differential rate of binge and heavy drinking signified a need to empirically report the effects of stress when it comes to excessive alcohol consumption. These numbers also suggested that the regulations may have only inhibited social drinking, and the regulations that indirectly limited individuals' access to alcohol did not necessarily reduce the rates of binge and heavy drinking. In fact, available evidence suggested that there was an astronomical increase in online alcohol sales (NielsenIQ 2020). Nowadays, relative to social drinking, at-home drinking may have become a new public health concern specific to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (Castaldelli-Maia et al. 2021).

Overall, our results supported our first hypothesis regarding the positive associations between stress and excessive alcohol consumption. With crude (i.e., covariates unadjusted) data, results showed that each unit increase in stress level was associated with a 65% increase in the likelihood of reporting binge drinking and a 161% increase in the likelihood of reporting heavy drinking. The expected associations also held after controlling for the impacts of demographic, socioeconomic, and health covariates, and stress specific to COVID-19. The results also supported the second hypothesis that difference in health insurance coverage would determine the strength of the associations between stress and alcohol consumption. In other words, while individuals with private health insurance were susceptible to excessive alcohol consumption under stress, those who did not have private health insurance coverage were much more susceptible when under stress during this challenging time. The patterns of the findings for the interaction terms also varied for binge and heavy drinking—in line with what the ex ante moral hazard hypothesis would predict, our results showed that publicly insured adults seemed to be more susceptible to binge drinking. On the other hand, the uninsured adults were substantially more likely to report heavy drinking in the face of increased levels of stress during the pandemic.

Strengths and limitations

An important contribution of the present study is that we explored whether and to what extent the negative impacts of stress on excessive alcohol consumption could vary among adults of different health insurance statuses. To address the research questions in a timely fashion, we conducted secondary analyses of the readily available 2020 Community Health Survey. The survey offered an opportunity of using a regionally representative dataset for which the data were rigorously collected. Most of the survey responses were designed with a Likert-type scale to capture the nuance of variables that could not be achieved with a dichotomous scale. Data were weighted, which allows for generalizing our findings to the Northern Larimer County population. In addition, the analyses were controlled for an array of covariates, which, to some extent, increased the reliability of our findings.

Still, the interpretation and generalizability of the findings would require caution. One major limitation was inherent to the cross-sectional nature of our data and the study design. The characteristics and behaviors of interest were assessed at a single time point, so we could not systematically evaluate and control for individuals' baseline levels of stress and alcohol consumption before the survey period. Similarly, under all circumstances, stress and socioeconomic and demographic characteristics would not be the only cause leading to excessive alcohol consumption. Alternative causes and covariates (e.g., genes; Anthenelli and Grandison 2012) not included in the current analyses are ideal but not possible to control for the current study. Finally, the self-report data were also associated with potential biases and measurement errors (e.g., response bias, recall bias, social desirability, or time-to-time variation in responses). In particular, self-report of alcohol consumption tends to be underestimated, as alcohol intake is notoriously susceptible to social desirability biases (Davis et al. 2010). There were also a few analytical concerns. For example, we had a relatively small sample of uninsured adults (n = 21) and adults with Medicaid (n = 35) compared to privately insured adults (n = 495). Although the chi-square test of independence does not assume equality in cells, the logistic models tend to not converge well with smaller sample sizes and worsen with sporadic missing values in key variables.

Future directions and policy implications

With refined analytical strategies (e.g., creating latent typologies of risk profiles among publicly insured and uninsured adults), future research could offer more comprehensive and holistic views regarding the effect of stress on health and health behaviors. Findings drawn from the study would hopefully raise awareness of increased social disparity in stress and excessive alcohol consumption during the pandemic. In all regards, quality primary care visits for adults reporting high levels of stress could be an alternative coping strategy to help intervene in problem drinking. However, our results also implied that providing public health insurance may not be sufficient for relieving the effect of stress on binge drinking. Thus, when it comes to eliminating risky alcohol consumption, policies and interventions may need to differentiate patterns of excessive alcohol consumption as the targets of intervention. Providing access to Medicaid for adults aged 18 to 64 may not be a panacea, and they would need to pay special attention to publicly insured adults at higher risk of binge drinking. Individuals who do not qualify for public health insurance (e.g., Medicaid) may still be eligible for some affordable marketplace private insurance. In these circumstances, our results highlighted a need for statewide and/or national efforts in reaching out to qualified uninsured adults to close the insurance coverage gap. Health First Colorado via Connect for Health Colorado, and the Affordable Care Act at both the state and national levels are examples of promising ways to effectively reduce the detrimental consequences of excessive drinking during a stressful time.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from Health District of the Northern Larimer County (Sue Hewitt shewitt@healthdistrict.org).

Code availability

SAS code for the analyses is openly available in the Open Science Forum at https://osf.io/p8zd9/

References

Anthenelli R, Grandison L (2012) Effects of stress on alcohol consumption. Alcohol Res: Curr Rev 34:381–382

Castaldelli-Maia JM, Segura LE, Martins SS (2021) The concerning increasing trend of alcohol beverage sales in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic. Alcohol 96:37–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2021.06.004

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022) Binge drinking. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/binge-drinking.htm. Accessed 17 December 2022

Cohen S, Gianaros PJ, Manuck SB (2016) A Stage model of stress and disease. Perspect Psychol Sci 11:456–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616646305

Collins CE (2016) Associations between socioeconomic factors and alcohol outcomes. Alcohol Res: Curr Rev 38:83–94

Commins F (2020) Health insurance survey finds widespread coverage gaps, financial stress. Health Leaders. https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/strategy/health-insurance-survey-finds-widespread-coverage-gaps-financial-stress. Accessed 17 December 2022

Dave D, Kaestner R (2009) Health insurance and ex ante moral hazard: Evidence from Medicare. Int J Health Care Fin Econ 9:367–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-009-9056-4

Davis CG, Thake J, Vilhena N (2010) Social desirability biases in self-reported alcohol consumption and harms. Addict Behaviors 35:302–31110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.001

Davis K, Stremikis K, Squires D, Scheoen C (2014) Mirror, mirror on the wall, 2014 update: How the U.S health care system compares internationally. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2014/jun/mirror-mirror-wall-2014-update-how-us-health-care-system Accessed 17 December 2022

Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R et al (2020) Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diab Metab Syndrome 14:779–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035

Greenfield LA (1998) Alcohol and crime: An analysis of national data on the prevalence of alcohol involvement in crime. In National Symposium on alcohol abuse and crime

Grossman ER, Benjamin-Nelson SE, Sonnenschein S (2020) Alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Cross-sectional survey of US adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:9189. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249189

Horton D (1943) The functions of alcohol in primitive societies: A cross-cultural study. Quart J Stud Alcohol 4:199–320. https://doi.org/10.15288/qjsa.1943.4.199

Kanny D, Brewer RD, Mesnick JB et al (2015) Vital signs: Alcohol poisoning deaths in the United States, 2010-2012. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6353a2.htm?s_cid=mm6353a2_w. Accessed 17 December 2022

Kim JU, Majid A, Judge R et al (2020) Effect of COVID-19 lockdown on alcohol consumption in patients with pre-existing alcohol use disorder. Lancet: Gastroenterol Hepatol 5:886–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30251-X

National Institutes on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2020) Drinking level defined. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking. Accessed 17 December 2022

Neill E, Meyer D, Toh WL et al (2020) Alcohol use in Australia during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic: Initial results from the COLLATE project. Psychiat Clin Neurosci 74:542–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13099

NielsenIQ (2020) Covid-19 fuels a 50% increase in omni-channel retail shopping across the U.S. https://nielseniq.com/global/en/insights/analysis/2020/covid-19-fuels-a-50-increase-in-omnichannel-shopping-across-the-u-s/. Accessed 17 December 2022

Rahe RH, Meyer M, Smith M et al (1964) Social stress and Illness onset. J Psychosomatic Res 8:35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(64)90020-0

Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE et al (2015) 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. Am J Prevent Med 49:73–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031

Smith GS, Branas CC, Miller TR (1999) Fatal nontraffic injuries involving alcohol: A meta-analysis. Annals Emerg Med 33:659–668

Sommers BD, Gawande AA, Baicker K (2017) Health insurance coverage and health: What the recent evidence tells us. New England J Med 377:586–593. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb1706645

Tamers SL, Okechukwu C, Bohl AA (2014) The impact of stressful life events on excessive alcohol consumption in the French population: Findings from the GAZEL cohort study. PloS One 9:e87653. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087653

Tran BX, Nguyen HT, Le HT et al (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on economic well-being and quality of life of the Vietnamese during the national social distancing. Front Psychol 11:565153. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565153

Turner RJ, Wheaton B (1997) Checklist measurement of stressful life events. In: Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon LU (eds) Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. Oxford University Press, pp 29–58

Ward BW, Martinez ME (2015) Health insurance status and psychological distress among US adults aged 18-64 years. Stress and Health 31:324–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2559

Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Sturm R et al (2002) Alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health care for uninsured and insured adults. Health Services Res 37:1055–1066. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.65.x

World Health Organization (2018) Global status report on alcohol and health. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639. Accessed 17 December 2022

Acknowledgements

We thank Angela Castillo, Sue Hewitt, and Suman Mathur from Northern Larimer County Health District for providing access to the dataset and for their valuable comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Han-Yun Tseng: manuscript writing, study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation; Sunhyun Chung: study concept and design, data interpretation, and manuscript writing; Lakshmi Ananda: study concept and manuscript revising; Linda Kim and Molly Gutilla: data acquisition, study concept, and manuscript revising.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) Committee of the Colorado State University [Protocol #3773].

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The participants have consented to the submission of the manuscript to the journal.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tseng, HY., Chung, S., Ananda, L. et al. Stress and excessive alcohol consumption among insured and uninsured adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Public Health (Berl.) (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-01927-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-01927-z