Abstract

Aim

I examined health/morbidity profiles across 20 countries, determined their associated demographic characteristics and risk factors and compared the distribution of these health/morbidity profiles across countries.

Subject and methods

I used population-based data drawn from the European Social Survey (N = 20092, 52% female, ages 40+) covering 20 mostly European countries (Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland) from 2014. Diverse indicators of health/morbidity were used, including self-rated health, self-rated disability, self-reported health problems and mental health symptoms using the CES-D. Latent class analysis was conducted to determine health/morbidity profiles across countries.

Results

I found that four distinct health profiles best describe overall health/morbidity status in the international sample, each associated with specific demographic and behavioural risk factors: ‘healthy’ profile (62% of participants), ‘unhappy but healthy’ profile (14%), ‘high morbidity, mostly physical’ profile (16%) and ‘high morbidity, mostly psychological’ profile (8%). With few exceptions, participants from Northern Europe and Western Europe were more likely to belong to the ‘healthy’ and the ‘unhappy but healthy’ profiles, whereas participants from Eastern Europe were more likely to belong to the ‘high morbidity, mostly physical’ profile. Distribution of the ‘high morbidity, mostly psychological’ profile appeared to be more uniform across regions.

Conclusions

Distinct morbidity/health profiles could be identified across countries, and countries varied regarding the relative distribution of these profiles. Specific prevention and treatment consequences associated with each profile are discussed. Future studies should further investigate the patterns of overall health and morbidity in Europe’s populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

With the increasing age of the world’s populations it is expected that there will be accompanying changes in health and health care, as for example proposed by the compression of morbidity and expansion of morbidity hypotheses (Gruenberg 1977; Fries 1980; Manton 1982; Fries et al. 2011). Consequently, several studies have been conducted to understand the health status of these populations. These studies have mostly focused on specific dimensions of health, such as specific diseases, self-rated health, depressive symptom burden or physical and cognitive functioning (e.g. Beller et al. 2019; Beller and Epping 2020; Safieddine et al. 2020; Schröder et al. 2020; Beller et al. 2020a; Sperlich et al. 2020; Grasshoff et al. 2021). However, health is seen as a complex biopsychosocial construct comprising diverging systems of diseases, syndromes and functioning (Huber et al. 2011). To adequately represent the multidimensionality of the individual health status, it is necessary to employ more comprehensive approaches that can account for multiple variables simultaneously.

One such approach that can capture the heterogeneity of individuals’ health status is latent class analysis (LCA), which has also been recommended in the literature (Zhou et al. 2018; Mori et al. 2020). LCA is a subset of classification methods, especially applicable for questionnaire data (Collins and Lanza 2010). LCA finds groups of cases with similar characteristics in multivariate categorical data. It has been favourably used in health studies (Ulbricht et al. 2018; Xiao et al. 2019; e.g. Mori et al. 2020). However, to my knowledge, no studies have used this approach to identify health/morbidity profiles in international comparisons of health status. This will be the focus of the current study. The study question is: Which health profiles can be identified internationally, and how do proportions of these profiles differ across countries? Thereby, the current study will be useful in understanding international variations in health status and morbidity. It will also inform public health policies, such as treatment guidelines and the development of targeted interventions approaches associated with each profile.

Methods

Sample

Data were drawn from the public release of the 7th round of the European Social Survey (ESS) that aims to provide comparative data on attitudes, beliefs and behaviour patterns of the various populations in Europe (Jowell et al. 2007). The ESS also includes rotating modules, which are dedicated to specific themes. I used data from the 20 countries (Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland) that participated in the 7th round of the ESS, sampled in 2014, which included a rotating module relating to health. To date, only the 7th round incorporated measures of overall health in the ESS, and as such only this wave could be included in the current study. The ESS provides population-based cross-sectional samples of non-institutionalized participants aged 14 years and older with the interviews conducted face-to-face at the respondent’s place of residence. In this study, only data from middle-aged and older adults will be used (ages 40+). Thusly, population-based cross-sectional samples of first-time responders were obtained. Response rates varied between 31% and 74% per country (Austria 57%, Belgium 68%, Czechia 52%, Denmark 60%, Finland 63%, France 51%, Germany 31%, Great Britain 44%, Hungary 53%, Ireland 61%, Israel 74%, Lithuania 69%; Netherlands 59%, Norway 54%, Poland 66%, Portugal 43%, Slovenia 52%, Spain 68%, Sweden 50%, Switzerland 53%). All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. After excluding participants with missing values listwise (approx. 20% of the sample), a final sample size of N = 20092 resulted (with country sample sizes ranging from n = 622 in Slovenia to n = 1867 in Germany).

Measures

Health/morbidity was measured with multiple instruments, including self-rated health, self-reported disability, self-reported health problems and the items of the Centre of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale 8 Item Version (CES-D 8). Self-rated health was measured by asking about participant’s self-rated health with answer options ranging from ‘very bad’, ‘bad’, ‘fair’, ‘good’ to ‘very good’. Self-rated health was dichotomized such that possible scores of (1) ‘very bad or bad health’ and (0) ‘fair, good and very good’ resulted. Furthermore, disability was measured by asking participants whether they were hampered in their daily activities. Participants could choose to response with either ‘no’, ‘yes to some extent’ or ‘yes a lot’. The latter two answer categories were combined such that a disability score of (0) represents ‘has no disability’ and (1) represents ‘has disability’. Health problems were measured by inquiring whether participants had health problems in the past 12 months regarding a list of items, including pain in back, pain in arms and hands, pain in legs and feet, stomach problems, skin problems, diabetes, breathing problems and heart problems. Pain in back, pain in arms and hands, pain in legs and feet was combined into one item ‘pain in back or extremities’ indicating whether participants reported pain in at least one of the three body areas. Scores of (0) indicate no problems regarding these health aspects, whereas scores of (1) indicate problems. Regarding the CES-D 8, multiple studies have demonstrated the scale’s validity, reliability and applicability to measure affective and somatic depressive symptoms in different cultures and throughout the lifespan (Karim et al. 2015; Vilagut et al. 2016; Kliem et al. 2020a, b; Beller et al. 2020b). The CES-D 8 measures the frequency of depressive symptoms, including affective and somatic components, in the week prior to the interview. Participants were asked whether they ‘felt depressed’, ‘felt lonely’, ‘felt sad’, (reverse scored) ‘were happy’, (reverse scored) ‘enjoyed life’, ‘felt everything was an effort’, ‘had restless sleep’ and ‘could not get going’. Participants could choose to respond with one of four response options ranging from ‘none or almost none of the time’, ‘some of the time’, and ‘most of the time’ to ‘all or almost all of the time’. Answers with ‘most of the time’ or ‘all or almost all of the time’ were coded as (1), other answer options as (0). Furthermore, information regarding participant’s health behaviours (less than weekly fruit consumption, less than weekly vegetables consumption, no physical exercise in previous week, daily smoking, daily alcohol consumption, obesity, general care contact in previous 12 months, specialist care contact in previous 12 months) was measured in such a way that scores of (0) represent the absence of the risk factor and scores of (1) represent the applicability of the risk factor. In general, all items were recoded such that scores of (1) represent morbidity/worse health outcomes. In addition, age, sex, education (measured via the years of full-time education completed) and income were measured. Income was measured by presenting participants with a list of 10 income categories, which represent the actual countries’ income deciles. Participants were asked to denote the income decile to which their household income belongs, such that answer options could range from (1) ‘lowest income decile’ to (10) ‘highest income decile’.

Data analysis

First, descriptive statistics of all variables across and within countries were computed. Then latent class analysis (LCA) was conducted, a statistical technique based on maximum likelihood estimation that identifies groups of similar cases, as defined by specific combinations of observed variables (Collins and Lanza 2010). In the case of the current study on health/morbidity profiles, groups of participants with similar health/morbidity characteristics were identified. Via LCA it was then possible to assign group membership to each participant by estimating the probability of the participant belonging to each subgroup. Participants were assigned class memberships based on modal probabilities. Then, prevalence of profiles across and within countries was calculated and demographic and risk factors were calculated for each profile. All statistical analyses were performed with R.

Results

Overall, participants were on average 59.7 (standard deviation [SD] = 12.3) years old, with 52% being female. Participants had on average 12.6 (SD = 4.2) years of education and belonged on average to the 5.3 decile regarding their country’s average household income (SD = 2.8). Furthermore, only 10% reported that they had bad health and 33% reported that they were limited in their daily activities. Further sample statistics are depicted in Table 1. Sample statistics for each country are reported in Table 2 and Table 3.

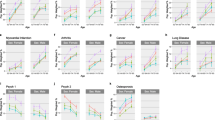

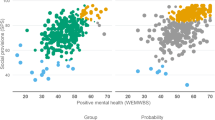

To determine health/morbidity profiles, latent class analysis was conducted. Via a scree plot, it was found that a four-class solution best fit the data (Fig. 2). Based on a plot of the class-specific response probabilities (Fig. 1), these profiles can be described as: ‘healthy’ profile (62% of participants; lowest probabilities of reporting morbidity regarding each aspect); ‘unhappy but healthy’ profile (14% of participants; very high probabilities of reporting unhappiness and no joy but comparatively low probabilities regarding each other indicator); ‘high morbidity, mostly physical’ profile (16% of participants; high probabilities of reporting morbidity on all indicators, with the highest probabilities of reporting physical morbidity indicators among all profiles); ‘high morbidity, mostly psychological’ profile (8% of participants; high probabilities of reporting morbidity on all indicators, with highest probabilities of reporting affective mental and affective somatic morbidity indicators among all profiles).

Furthermore, these profiles also varied regarding their associated socio-demographic and risk behaviour characteristics, as seen in Table 4. Participants belonging to the ‘healthy’ profile were in general slightly younger, more likely male, slightly more educated and had a slightly higher income. Furthermore, they had the lowest proportion of unmet needs for health care, the lowest contact with the health care system as well as the lowest prevalences of behavioural risk factors. In comparison to the ‘healthy’ profile, participants in the ‘unhappy but healthy’ profile were slightly more likely to be female, slightly less educated and had a slightly lower household income. Furthermore, they had a higher proportion of unmet needs for health care, similar rates of contact with the health care system and similar rates of prevalence of behavioural risk factors; only the prevalence of lack of physical exercise was much higher in this profile as compared to the ‘healthy’ profile. Participants belonging to the ‘high morbidity, mostly physical’ profile were, in comparison to the other profiles, slightly older, more likely to be female, slightly less educated and had a slightly lower income. Furthermore, they had the highest proportion of unmet needs for health care, higher probabilities of having had contact with the health care system and high prevalences of behavioural risk factors. Notably, prevalence of lack of physical exercise was highest in this profile. Finally, participants belonging to the ‘high morbidity, mostly psychological’ profile were, in comparison to the other profiles, slightly older, more likely to be female, the least educated and had the lowest household incomes. Furthermore, they had a high proportion of unmet needs for health care, and the highest contact with the health care system among the profiles as well as high prevalences of behavioural risk factors.

Distribution of profiles across countries is depicted in Table 5. With few exceptions, participants from Northern Europe and Western Europe were more likely to belong to the ‘healthy’ and the ‘unhappy but healthy’ profiles, especially Norway, Ireland and Denmark, whereas participants from Eastern Europe were more likely to belong to the ‘high morbidity, mostly physical’ profile, i.e. Poland, Hungary and Czechia. Results in Southern Europe and the distribution of the ‘high morbidity, mostly psychological’ profile appeared to be more varied and equally distributed across geographical regions. Notably, as compared to the other countries from Western Europe, Germany had a much lower proportion of participants belonging to the ‘healthy’ profile, and a much higher proportion of participants belonging to the ‘high morbidity, mostly psychological’ profile. Also, compared to the other countries, participants from Lithuania and Israel had a high prevalence of belonging to the ‘unhappy, but healthy’ profile.

Discussion

I investigated if and how the overall health status of the various European populations and Israel can be described more comprehensively and found empirical evidence for four health/morbidity profiles: (1) ‘healthy’, (2) ‘unhappy but healthy’, (3) ‘high morbidity, mostly physical’ and (4) ‘high morbidity mostly psychological’. International distribution of these profiles across countries was not random. Rather, as compared to the other countries, participants from countries in Northern and Western Europe tended to more likely belong to the ‘healthy’ profile and were less likely to belong to the ‘high morbidity mostly physical’ profile. Participants from Eastern Europe, however, were more likely to belong to the ‘high morbidity, mostly physical’ profile. Participants from countries of Southern Europe were more equally distributed across profiles. Therefore, the overall health/morbidity status seems to be clustered according to geographical regions.

These results suggest that there are supra-national variations in health status, seemingly specific to geographical regions. This supports theoretical considerations and practical approaches that define and investigate health as a complex interrelated system of at least physical health problems, mental health problems and aspects of functioning (Huber et al. 2011). Additionally, these results suggest that scientific studies on Europeans’ health status might not be limited to the countries they were conducted in but might be more generalizable within geographical regions. On the other hand, the current study also shows that there might be stark differences between regions such that generalizability between very different countries should not be automatically assumed (Henrich et al. 2010). This generalizability might also extend to prevention and treatment programs (St. Sauver et al. 2012). For example, based on the current results, a prevention approach that might have proven to be fruitful in Germany, might also be adaptable to France, but less so to Hungary.

Moreover, the current study suggests that the morbidity/health profiles are associated with specific socio-demographic and behavioural risk factors. Based on the results regarding the ‘unhappy but healthy profile’, more prevention efforts might be directed in medical care and prevention to those who appear to be healthy but report low levels of well-being (Tamosiunas et al. 2019; Trudel-Fitzgerald et al. 2019). As members of this profile were generally similar to the ‘healthy’ profile, but were much more likely to lack physical exercise, participants belonging to this profile might thus be much more likely to develop cardiovascular-related morbidity as they age (Nystoriak and Bhatnagar 2018; Kraus et al. 2019). Participants from both high morbidity profiles, on the other hand, were much more likely to report high levels of obesity. Thus, prevention and care for participants from these profiles might focus on preventing and treating obesity.

There are some limitations to the current study. First, the results of some countries diverged from main trends within regions. For example, Lithuania appeared to be very different from other countries in that a high proportion of participants were classified as belonging to the ‘unhappy’ profile. This is, however, in line with the literature, as Lithuania has been found to be among the countries with the highest suicide rates in the world, with increasing rates of social isolation as one potentially explaining factor (Värnik 2012; Zaborskis et al. 2016; Beller and Wagner 2018a, b, 2020). Additionally, as compared to the other countries from Western Europe, Germany had a low proportion of participants belonging to the ‘healthy’ profile. Germany, together with Poland, reported instead high proportions of participants belonging to the ‘high morbidity, mostly psychological’ profile. This is also in line with some previous studies, where increasing morbidity has been reported, especially for young and middle-aged adults in Germany and Poland (Beller et al. 2019, 2020b; Beller and Epping 2020). However, future studies must investigate the specific reasons for these cross-national variations empirically. As a second limitation, the current study could only use self-reports of health. As such, results might suffer from known self-report biases of health, especially regarding cross-cultural research (van de Vijver and Tanzer 2004; Bauhoff 2011). However, accepting these limitations, the current study could comprehensively study health/morbidity profiles and determine how these profiles vary across multiple countries. More research on health/morbidity profiles is needed. Given recent morbidity trends, it seems especially important to determine how the relative proportion of morbidity/health profiles has changed over time in the general population (Geyer and Eberhard 2021).

Availability of data and material

Data can be accessed for free after registration at https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/.

References

Bauhoff S (2011) Systematic self-report bias in health data: impact on estimating cross-sectional and treatment effects. Health Serv Outcomes Res Method 11:44–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-011-0069-3

Beller J, Bauersachs J, Schäfer A et al (2020a) Diverging Trends in Age at First Myocardial Infarction: Evidence from Two German Population-Based Studies. Sci Rep 10:9610. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66291-4

Beller J, Epping J (2020) Disability trends in Europe by age-period-cohort analysis: Increasing disability in younger cohorts. Disabil Health J 14:100948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100948

Beller J, Miething A, Regidor E et al (2019) Trends in grip strength: Age, period, and cohort effects on grip strength in older adults from Germany, Sweden, and Spain. SSM - Population Health 9:100456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100456

Beller J, Regidor E, Lostao L et al (2020b) Decline of depressive symptoms in Europe: differential trends across the lifespan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01979-6

Beller J, Wagner A (2018a) Disentangling loneliness: differential effects of subjective loneliness, network quality, network size, and living alone on physical, mental, and cognitive health. J Aging Health 30:521–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264316685843

Beller J, Wagner A (2018b) Loneliness, social isolation, their synergistic interaction, and mortality. Health Psychology 37:808–813. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000605

Beller J, Wagner A (2020) Loneliness and health: the moderating effect of cross-cultural individualism/collectivism. Journal of Aging and Health 089826432094333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264320943336

Collins LM, Lanza ST (2010) Latent class and latent transition analysis: with applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Wiley, Hoboken

Fries JF (1980) Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity. N Engl J Med 303:130–135. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198007173030304

Fries JF, Bruce B, Chakravarty E (2011) Compression of morbidity 1980–2011: a focused review of paradigms and progress. J Aging Res 2011:1–10. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/261702

Geyer S, Eberhard S (2021) Später krank und länger gesund? Die Morbiditätskompression und ihre Alternativen

Grasshoff J, Beller J, Kuhlmann BG, Geyer S (2021) Increasingly capable at the ripe old age? Cognitive abilities from 2004 to 2013 in Germany, Spain, and Sweden. PLoS ONE 16:e0254038. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254038

Gruenberg EM (1977) The Failures of Success. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly Health and Society 55:3. https://doi.org/10.2307/3349592

Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A (2010) The weirdest people in the world? Behav Brain Sci 33:61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L et al (2011) How should we define health? BMJ 343:d4163–d4163. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4163

Jowell R, Roberts C, Fitzgerald R, Eva G (eds) (2007) Measuring attitudes cross-nationally: lessons from the European Social Survey. SAGE, Los Angeles ; London

Karim J, Weisz R, Bibi Z, Ur Rehman S (2015) Validation of the eight-item center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) among older adults. Curr Psychol 34:681–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9281-y

Kliem S, Beller J, Tibubos AN et al (2020a) A reanalysis of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D) using non-parametric item response theory. Psychiatry Res 290:113132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113132

Kliem S, Beller J, Tibubos AN, Brähler E (2020b) Normierung und Evaluation der Messinvarianz der 8-Item-Kurzform der Center of Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D-8). Zeitschrift für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie 66:259–271. https://doi.org/10.13109/zptm.2020.66.3.259

Kraus WE, Powell KE, Haskell WL et al (2019) Physical activity. All-cause and cardiovascular mortality, and cardiovascular disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc 51:1270–1281. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001939

Manton KG (1982) Changing concepts of morbidity and mortality in the elderly population. Milbank Memorial Fund Q Health Soc 60:183. https://doi.org/10.2307/3349767

Marôco J (2021) Portugal: the PISA effects on education. In: Crato N (ed) Improving a country’s education. Springer, Cham, pp 159–174

Mori M, Krumholz HM, Allore HG (2020) Using latent class analysis to identify hidden clinical phenotypes. JAMA 324:700. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2278

Nystoriak MA, Bhatnagar A (2018) Cardiovascular effects and benefits of exercise. Front Cardiovasc Med 5:135. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2018.00135

Safieddine B, Sperlich S, Beller J et al (2020) Socioeconomic inequalities in type 2 diabetes in employed individuals, nonworking spouses and pensioners. SSM - Population Health 11:100596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100596

Schröder S, Beller J, Golpon H, Geyer S (2020) Are there social gradients in the occurrence of lung cancer and in the survival of lung cancer patients? Findings from an observational study using German claims data of Lower Saxony. BMJ Open 10:e036506. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036506

Sperlich S, Beller J, Epping J, et al (2020) Trends in self-rated health among the elderly population in Germany from 1995 to 2015 – the influence of temporal change in leisure time physical activity. BMC Public Health 20:113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8218-7

St. Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL et al (2012) Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester epidemiology project. Mayo Clinic Proc 87:151–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009

Tamosiunas A, Sapranaviciute-Zabazlajeva L, Luksiene D et al (2019) Psychological well-being and mortality: longitudinal findings from Lithuanian middle-aged and older adults study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 54:803–811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01657-2

Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Millstein RA, von Hippel C et al (2019) Psychological well-being as part of the public health debate? Insight into dimensions, interventions, and policy. BMC Public Health 19:1712. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8029-x

Ulbricht CM, Chrysanthopoulou SA, Levin L, Lapane KL (2018) The use of latent class analysis for identifying subtypes of depression: a systematic review. Psychiatry Research 266:228–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.003

van de Vijver F, Tanzer NK (2004) Bias and equivalence in cross-cultural assessment: an overview. European Review of Applied Psychology 54:119–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2003.12.004

Värnik P (2012) Suicide in the world. IJERPH 9:760–771. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9030760

Vilagut G, Forero CG, Barbaglia G, Alonso J (2016) Screening for depression in the general population with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D): a systematic review with meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 11:e0155431. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155431

Xiao Y, Romanelli M, Lindsey MA (2019) A latent class analysis of health lifestyles and suicidal behaviors among US adolescents. J Affect Disord 255:116–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.031

Zaborskis A, Sirvyte D, Zemaitiene N (2016) Prevalence and familial predictors of suicidal behaviour among adolescents in Lithuania: a cross-sectional survey 2014. BMC Public Health 16:554. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3211-x

Zhou M, Thayer WM, Bridges JFP (2018) Using latent class analysis to model preference heterogeneity in health: a systematic review. PharmacoEconomics 36:175–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-017-0575-4

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge the European Social Survey for providing me with the data used in the current study.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This paper was funded by the German Research Foundation (GE 1167/15-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for original data collection was obtained from the ESS ERIC Research Ethics Board.

Consent to participate

Informed consent by participants for data collection was obtained.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beller, J. Morbidity profiles in Europe and Israel: international comparisons from 20 countries using biopsychosocial indicators of health via latent class analysis. J Public Health (Berl.) 31, 1329–1337 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01673-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01673-0