Abstract

Aim

Former unaccompanied immigrant minors (UMs) now living in the USA are a uniquely vulnerable population. The US Office of Refugee Resettlement shelters provide health services, but most are discontinued once UMs leave the shelters. A systematic review was therefore designed to quantify access to medical, mental, and dental healthcare services by former UMs living in the USA.

Subject and methods

The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO. A search was made in Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and Academic Search Complete in June 2020. Full-text review, data extraction, and data analysis were completed by all authors.

Results

Searches returned a total of 2646 studies, of which 15 met all eligibility criteria. There was an overlap in the services investigated in the studies — 13 assessed mental health, ten assessed medical, and four included dental care. Sample sizes ranged from one to 4809, and there was a wide range of study designs. Some studies included multiple locations. Nine studies demonstrated success in community-based clinics or programs; one in a hospital, four in schools, three in group living settings, and one in U.S. Customs Border Patrol (CBP) custody. Three studies explored access to services post-release from shelters.

Conclusions

Healthcare programs at shelters, schools, and in the community have provided some screening and diagnosis of medical, mental health, and dental conditions for UMs, but multiple financial and cultural barriers make ongoing treatment difficult to access. Long-term studies following UMs in shelters and post-release through adulthood are needed to help create new, or modify existing, programs, to adequately support UMs now living in the USA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Over 400,000 asylum-seeking unaccompanied minors (UMs) have crossed the US–Mexico border since 2003, and rates of UMs fleeing to the US have been rising since, with 76,020 UMs apprehended at the US–Mexico border in 2019 (US CBP 2021). Although the US government classifies minors who cross the border without their parents as unaccompanied alien children (UAC), due to the negative and demeaning connotation of the terminology, UAC are referred to commonly and in this paper as UMs. UMs are uniquely vulnerable and different from unaccompanied refugee minors (URMs), because URMs come to the USA with legal status. UMs, however, are seeking asylum and until it is granted, they do not have legal status. The majority of UMs in the USA migrated from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, a region referred to as the “Northern Triangle” of Central America (Kandel 2019, Mossaad 2018). UMs from the Northern Triangle are a unique demographic of migrants entering the USA, and one for whom treatment, care, and long-term outcomes are largely unknown. Once UMs cross the US–Mexico border and enter the USA, they are often apprehended and detained by CBP for up to 72 h and then transferred to US Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) shelters located throughout the US. These shelters provide food, clothing, education, medical services, and case managers who work towards unification with a vetted caregiver who can act as a sponsor during immigration proceedings (Roth and Grace, 2015). The average stay for a UM in an ORR shelter in 2020 was 152 days, dependent upon the time needed to find a vetted caregiver. This statistic was up from the average of 66 days in 2019 (ORR 2021, Roth and Grace, 2015).

While ORR shelters are mandated to provide initial medical, dental, and mental health screenings and care, most services are discontinued once UMs leave the shelters, and there is no process in place to ensure follow-up. Access to healthcare services for former UMs is difficult post-release because they are often uninsured and living with under-resourced families who have limited access to services. With the upward trend in migration of UMs, the USA should strive to better understand the needs of contemporary migrants such as families and children seeking refuge from violence and poverty (Budiman 2020).

UMs often hide in the shadows due to a variety of legal and political fears (Hasson III et al., 2018). This is in part because the USA lacks universal immigration laws, policies, and agreements. Established laws and policies often conflict on the best treatment for UMs from a legal perspective (Kandel 2019). The majority of UMs arriving in the USA present with claims for asylum due to substantial fears of violence in their home countries (Sawyer and Márquez, 2017). The effects of trauma, extreme poverty, and discrimination pre-migration, during migration, and post-migration are likely to have long-term impacts on youth who arrived unaccompanied in the USA (Teitel 2016). While very few studies on the physical and mental health of UMs have been published in the USA, UMs are at high risk for developing physical and mental health conditions due to poor social determinants of health such as economic stability, education, healthcare, neighborhood/environment, and social context, both before, during, and after migration (Cardoso 2018, Chang 2019).

The precarious legal situations in which UMs live, in conjunction with past and current traumatic experiences, are likely to continue to impact the lives of these vulnerable youth. The shortage of bilingual, bicultural, and competent professionals, the lack of insurance coverage, and fear of exposure due to immigration status likely contribute to inequities in all forms of healthcare for UMs (Bishop and Ramirez, 2014). However, specific rates of healthcare access and utilization among current or former UMs are unknown. This systematic review aims to analyze literature on UMs in the USA to elucidate the extent to which UMs access and utilize health services.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with guidelines set by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO. PROSPERO is an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in healthcare, social care, welfare, and public health (PROSPERO 2021). From the original PROSPERO submission, only the title was changed. The original submission to PROSPERO had the title “Systematic Review of Utilization of and Access to Healthcare Services by Former Unaccompanied Minors”.

In June 2020, a medical librarian conducted a systematic review of the electronic databases Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and Academic Search Complete. The search was limited to those studies published in the USA. Language restrictions included English-only articles, and two authors were contacted for additional information and full-text articles. Medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and keywords used, as well as the search strategies performed, are shown in Table 1. The Ovid MEDLINE strategy was then translated to Embase, Scopus, and Academic Search Complete, resulting in a total of 1555 de-duplicated results. Articles that met search criteria were uploaded into the Rayyan database for blinding and organizational purposes. Screening of the articles was completed by three authors based on information provided in the abstracts. A minimum of two researchers reviewed each abstract independently. Selection of relevant articles was based on the information obtained from the abstracts and was agreed upon in discussion. If the abstract was not available, the full text was examined. In the case of discrepancies between two researchers, the full-text original paper was reviewed and read by all three researchers, and agreement reached after a group discussion.

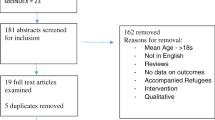

After the initial screening, 47 articles were reviewed by SM, NH, and AG. One article was excluded since the full text was in a foreign language. Seventeen articles were excluded due to reporting on the wrong intervention, as the studies did not directly address utilization of healthcare services by UMs. One article was eliminated because it contained the wrong outcome by studying a health-related topic without addressing access to healthcare. Three articles were excluded due to being the wrong publication types, and 11 others since they studied youth who were not UMs living in the USA. Following review and discussion, 15 scholarly articles were finally included in this review and reviewed by all authors. Figure 1 delineates the PRISMA flow chart, adapted from Moher et al. (Moher et al., 2009).

Results

Fifteen studies met inclusion criteria for this review. Sample sizes ranged from 1 to 4809, and the study design included program evaluations, quantitative studies, qualitative studies, longitudinal mixed-method studies, outcome evaluations, auto-ethnographic interviews, and case studies. Table 2 describes the key characteristics and results of the publications in alphabetical order by the first author’s last name.

Thirteen studies directly evaluated healthcare access by adolescents or young adults. A total of 5586 immigrant youths were assessed or screened for medical, dental, or mental healthcare conditions. Of these, 5200 participants were identified as UMs or former UMs originating from Mexico or Central America. Six studies differentiated participants by country of origin (total n = 178), with UMs being specifically from Honduras (n = 64) 36%, El Salvador (n = 51) 29%, Guatemala (n = 55) 31%, and Mexico (n = 8) 4%. Seven studies classified participants as being from “Mexico or Central America.” Additionally, six studies identified the gender of participants (n = 209) in which males accounted for 65%. Three studies utilized health provider or key informant (lawyers, social workers, educational professionals, community advocates, child sponsors, and foster parents) perspectives.

The 15 studies included a wide range of services in a variety of locations. Some included multiple services and/or multiple locations. Nine studies (60%) were in a community-based clinic or program, one (6.7%) was in a hospital, four (26.7%) were set in schools, three (20%) were in group living settings such as shelters or long-term foster care, and one (6.7%) was set in a CBP setting. Three studies specifically explored access to care services among UMs post-release from shelters or foster care.

There was overlap in the services assessed in each of the studies. Specifically, 13 assessed mental health care services, ten assessed medical care, and four included dental care. None of the studies addressed use of traditional practitioners or cultural healers.

Discussion

This systematic review on UMs’ access to healthcare demonstrates limited use of medical, dental, and mental health services by this vulnerable population. Barriers to accessing care are substantial and common. Qualitative studies, with data provided by UMs and professionals who work closely with UMs, report that healthcare access barriers include legal status, limited health insurance coverage, geography (difficulty reaching UMs living all over the USA), costs, availability of trained and Spanish-speaking providers, guardians’ consent for youth, and difficulty obtaining special authorizations for referrals. Healthcare programs at shelters, at schools, and in the community did provide screening and diagnosis of medical, mental health, and dental conditions, but ongoing therapy and treatment were difficult to access.

This review highlights that UMs appear to be successful in accessing care if living in a residential setting such as a foster home or shelter. UMs are also successful in obtaining care when it is provided in a holistic, coordinated, and comprehensive manner, such as in an integrated clinic or city-supported program that offers medical, mental health, and/or legal services. UMs also accessed services successfully when they were provided in school-based settings, but school-based clinics and services like these are uncommon. It should be noted that even in residential and school-based settings, where services such as screenings were accessed, referrals to specialists and ongoing mental health therapy were much more difficult to obtain. At times, these barriers made receiving care impossible. Due to a lack of empirical evidence, rates of access and use of healthcare services outside the school and shelter settings are less clear. However, studies following UMs post-release suggest that access to care is possible when needed. What is not known is how and where UMs are obtaining care, who is covering the cost of the care, and whether they are receiving culturally sensitive and trauma-informed care.

Studies have been published on access to care for URMs, which are not the same population as UMs, however. URMs are former unaccompanied refugee minors who are deemed to have refugee status by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UN Refugee Agency 2021). URMs who are living in the USA with legal status may have trauma and migration histories similar to those of UMs, but they face different challenges and barriers once they have reached the USA. Until, and if, UMs receive asylum through the judicial system, they have limited access to healthcare services and are subject to deportation. Very few UMs are granted asylum in the USA. As Kennedy noted: “URMs receive access to care until the age of 21 but UMs’ access to services ends upon release from the ORR shelters. UMs experience barriers to healthcare such as stigma around mental illness, poverty, food insecurity, lack of insurance, language difficulties, and cultural barriers. Short-term impacts of not receiving adequate holistic healthcare may affect immigration processes/proceedings, and long-term effects may include co-occurring substance abuse, lower educational attainment, unemployment, homelessness, and imprisonment” (Kennedy 2013).

Access to care for UMs is a recognizable need and an important area of research, as the number of UMs living in the US is increasing. These high-risk, vulnerable minors need access to all forms of healthcare, and our system should be strategic about providing that care. No comprehensive healthcare-specific governmental programs are in place to assist all UMs post-release. As initial screenings and treatments are conducted in ORR shelters, a collaborative process including ORR shelters, non-governmental organizations, and community partners is imperative to provide former UMs with access to comprehensive healthcare. Such a program could be modeled similarly to programs that support US-born foster children and children in the youth URM foster care system. Since coordination is critical to success, specialists such as caseworkers can be hired, trained, and assigned to follow and support UMs until they reach adulthood. Collaboration with schools and legal providers may be necessary to adequately reach and support UMs in such a program.

Availability of data and materials

Data available upon request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Acuña A, Escudero PV (2015) Helping those who come here alone. Phi Delta Kappan 97(4):42–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721715619918

Baily CDR, Henderson SW, Tayler R (2016) Global mental health in our own backyard: an unaccompanied immigrant child’s migration from El Salvador to New York City. J Clin Psychol 72(8):766–778. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22358

Bishop DS, Ramirez R (2014) Caring for unaccompanied minors from Central America. Am Fam Physician 90(9):656–659

Budiman A (2020) Key findings about U.S. immigrants. Pew Research Center, Washington DC. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/. Accessed 2020, September 22

Cardoso JB (2018) Running to stand still: trauma symptoms, coping strategies, and substance use behaviors in unaccompanied migrant youth. Child Youth Serv Rev 92:143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.04.018

Chang CD (2019) Social determinants of health and health disparities among immigrants and their children. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 49(1):23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2018.11.009

Crea TM, Lopez A, Hasson RG, Evans K, Palleschi C, Underwood D (2018) Unaccompanied immigrant children in long term foster care: identifying needs and best practices from a child welfare perspective. Child Youth Serv Rev 92:56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.12.017

Descilo T, Greenwald R, Schmitt TA, Reslan S (2010) Traumatic incident reduction for urban at-risk youth and unaccompanied minor refugees: two open trials. J Child Adolesc Trauma 3(3):181–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361521.2010.495936

Evans K, Pardue-Kim M, Crea TM, Coleman L, Diebold K, Underwood D (2018) Outcomes for youth served by the Unaccompanied Refugee Minors foster care program: a pilot study. Child Welfare 96(6):87–106

Hasson RG III, Crea TM, McRoy RG, Lê ÂH (2018) Patchwork of promises: a critical analysis of immigration policies for unaccompanied undocumented children in the United States. Child Fam Soc Work 24(2):275–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12612

Jani JS (2017) Reunification is not enough: assessing the needs of unaccompanied migrant youth. Fam Soc 98(2):127–136. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.2017.98.18

Kandel A (2019) Unaccompanied alien children: an overview (report no. 43599) Congressional Research Service, Washington DC. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R43599.pdf. Accessed 2021, march 13

Katsounari I (2014) Integrating psychodynamic treatment and trauma focused intervention in the case of an unaccompanied minor with PTSD. Clin Case Stud 13(4):352–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650113512021

Kennedy EG (2013) Unnecessary suffering: potential unmet mental health needs of unaccompanied alien children. JAMA Pediatr 167(4):319–320. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1382

Linton JM, Kennedy E, Shapiro A, Griffin M (2018) Unaccompanied children seeking safe haven: providing care and supporting well-being of a vulnerable population. Child Youth Serv Rev 92:122–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.043

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mossaad N (2018) Annual flow report refugees and asylees: annual flow: 2018. US Dept of Homeland Security, Washington DC

Nyangoma EN, Arriola CS, Hagan J et al (2014) Hospitalizations for respiratory disease among unaccompanied children from Central America—multiple states, June–July 2014 (notes from the field). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63(32):698–699

Office of Refugee Resettlement (2021) Unaccompanied children: facts and data. The Administration for Children and Families, Washington DC. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/about/ucs/facts-and-data. Accessed 2021, January 11

PROSPERO (2021) A registry for systematic review protocols. University of York, York, UK. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#aboutpage. Accessed 2021, may 17

Roth BJ, Grace BL (2015) Falling through the cracks: the paradox of post-release services for unaccompanied child migrants. Child Youth Serv Rev 58:244–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.10.007

Sawyer CB, Márquez J (2017) Senseless violence against Central American unaccompanied minors: historical background and call for help. J Psychol 151(1):69–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2016.1226743

Schapiro NA, Gutierrez JR, Gonzalez JL, Dai JS, Gutierrez I (2016) Unaccompanied minors: breaking down barriers to health. J Adolesc Health 58(2):S21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.10.056

Schapiro NA, Gutierrez JR, Blackshaw A, Chen JL (2018) Addressing the health and mental health needs of unaccompanied immigrant youth through an innovative school-based health center model: successes and challenges. Child Youth Serv Rev 92:133–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.04.016

Teitel YH (2016) Medical and mental health needs of unaccompanied, undocumented adolescents in New York City: a qualitative, interview-based study. J Adolesc Health 58(2):S44–S45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.10.102

Tello AM, Castellon NE, Aguilar A, Sawyer CB (2017) Unaccompanied refugee minors from Central America: understanding their journey and implications for counselors. J Prof Couns 7(4):360–374. https://doi.org/10.15241/amt.7.4.360

Tomczyk S, Arriola CS, Beall B et al (2016) Multistate outbreak of respiratory infections among unaccompanied children, June 2014–July 2014. Clin Infect Dis 63(1):48–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw147

UNHCR (2021) Figures at a glance. UNHCR, Geneva. https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html — Accessed 2021, February 2

U.S. CBP (Customs and Border Protection) (2021) Southwest land border encounters. U.S. CBP (Customs and Border Protection), Washington DC. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-land-border-encounters. Accessed 2021, February 1

Funding

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SMM conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated the review process, screened and reviewed the articles, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

NH and AB helped design the study, screened and reviewed the articles, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

KL conducted the review in the databases, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

JC, AG, NG, and PS reviewed the articles, and they reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

This research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards expected and required of authors.

Ethics approval

Not applicable (not human subjects research).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Misra, S.M., Holdstock, N., Baez, J.C. et al. Systematic review of former unaccompanied immigrant minors’ access to healthcare services in the United States. J Public Health (Berl.) 30, 2605–2617 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01652-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01652-5