Abstract

Aim

The study aimed to determine trends in the prevalence of underweight, overweight, obesity and their putative risk factors in different cohorts from a representative population of adolescents in Central Italy.

Subject and methods

After random sampling, five cohorts of adolescents attending public high schools – aged 14 to 18 years – were evaluated from 2005 to 2018 (n: 25,174). Collected information included self-reported body mass index (BMI), descriptors of family environment, eating behaviour, physical activity, screen use, bullying victimisation, sexual behaviour (age at first intercourse, number of partners) and perceived psychological distress. For these data, between-cohort prevalence differences were used to esteem prevalence variations across time. In the 2018 cohort, the association between these factors and body weight was evaluated through multinomial regressions with sex-specific crude relative risk ratios for different BMI categories.

Results

An increased prevalence of overweight was observed for both boys and girls. The study outlined a transition towards higher parental education and unemployment, reduced soft drinks consumption and higher psychological distress. Sex-specific changes were observed for physical and sexual activity, and a rising percentage of girls reported being bullied and distressing family relationships. Parental education and employment, together with physical activity, confirmed to be protective factors against pathological weight. The latter clustered with reduced soft drinks consumption, bullying victimisation, early sexual activity, worse family relationships and higher distress.

Conclusion

An increased prevalence of both overweight and underweight was observed across time. Economic factors associated with unemployment and changes in behavioural patterns may have contributed to this trend.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

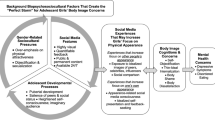

A steady increase in the prevalence of overweight among children and adolescents raised public concern in the past decades, given its long-term impact on individual health (Boyer et al. 2015). Excessive weight during adolescence is a multi-faceted phenomenon (Abarca-Gómez et al. 2017), and the identification of risk and protective factors may allow health institutions to establish adequate prevention programmes.

Within risk factors, lower socioeconomic status has been frequently reported (Rokholm et al. 2010), and sex differences – together with individual vulnerability (Devaux and Sassi 2013; Matthiessen et al. 2014) – were also described (Desai et al. 2009). A higher education level seems to exert a protective role against overweight (Apouey and Geoffard 2016), and a widespread educational expansion is likely to have contributed to reduced weight disparities in European countries (Etile 2014). The abovementioned social gradient is bound to the ‘low economic cost of becoming obese’ (i.e. the fact that energy-dense products are less expensive than healthier and fresh food) (Drewnowski and Specter 2004): indeed, the consumption of fruit and vegetables proved to diminish when employment rates and purchasing power fall (Milicic and DeCicca 2017). Furthermore, reduced physical activity and screen-based activities are associated with consumption of sweetened beverages (Gebremariam et al. 2015) and sedentary behaviour (Pearson and Biddle 2011; Börnhorst et al. 2015), whereas a lifestyle encompassing moderate to vigorous physical exercise has a protective role against overweight (Owen et al. 2010).

Beyond diet and lifestyle, adolescence overweight has been associated with a negative perception of body image, stigma (Puhl and Suh 2015), low self-worth (Danielsen et al. 2012) and bullying victimisation among peers (van Geel et al. 2014; Bacchini et al. 2015). Pathological weight is also known to be associated with risky sexual behaviour (Gordon et al. 2016), possibly because of underlying shared risk factors, such as childhood neglect or abuse (Gustafson and Sarwer 2004; Homma et al. 2012).

Family relationships have been implicated as well, since weight alterations are associated with high intra-familial distress (Cromley et al. 2010; Wertheim et al. 1992). More in general, overweight people tend to experience psychological difficulties, and to report a lower quality of life, eventually tied to mental health adverse outcomes (Needham and Crosnoe 2005; Hoare et al. 2016).

Considering the abovementioned factors, the present study aimed to investigate trends of prevalence of pathological weight in representative populations of adolescents of Central Italy across time, and to explore the role of environmental and behavioural factors associated with this condition. The present data are part of the largest epidemiological investigation on at-risk behaviour among Italian adolescents (Epidemiologia dei Determinanti dell'Infortunistica Stradale Toscana, EDIT).

Methods

Sample and data collection

Agenzia Regionale di Sanità (ARS) della Toscana enrolled a total of 32,665 adolescents – aged 14 to 18 years – attending public high schools of Tuscany (Italy), divided into five different cohorts from 2005 to 2018. The survey was carried in 2005, in 2008, in 2011, in 2015, and in 2018), and it consisted of a single, cross-sectional evaluation of the enrolled students. To avoid selection bias or inadequate representation of sex, age, family income, and geographic region, a subgroup of high schools was selected before each survey through a random sampling procedure, based on the complete sociodemographic data from the Regional Board of Studies. Subsequently, five classes were randomly chosen from different sections to avoid any bias related to specific characteristics of single school sections. Before inclusion in the study, the survey procedure was explained and informed consent was collected from participants, and from their parents or legal tutor (for individuals younger than 18 years old). The anonymous self-reported questionnaire was completed on a single occasion during school hours, and the confidentiality of participants was always ensured. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the sponsoring institution, and it was performed following the ethical standards contained in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Participants were excluded from analysis if informed consent was lacking, or if they did not report both their height and weight as requested, since it was not possible to calculate their body mass index (BMI). After excluding individuals who did not provide consent, the sample was checked for selective participation, to confirm that it did not significantly differ from the initial one regarding the criteria used for random sampling (i.e. sex, age, family income and geographic area where the students lived). The final sample included 25,174 adolescents: 4603 (1996 boys and 2607 girls) were enrolled in 2005; 5010 (2242 boys and 2768 girls) in 2008; 4448 (2404 boys and 2044 girls) in 2011; 4852 (2601 boys and 2251 girls) in 2015; and 6261 (3365 boys and 2896 girls) in 2018.

Measurements and variables

The dependent variable for analyses was self-reported BMI in kilograms per square meter (kg/m2), obtained from self-reported weight (kg) and height (m). BMI scores were divided into four categories based on normative cut-offs (Cole et al. 2000, 2007): ‘underweight’, ‘normal weight’, ‘overweight’ and ‘obesity’.

Behavioural, relational and sociodemographic factors were investigated through a self-reported questionnaire, which presented a progressive enrichment across different editions due to the implementation of new items.

Demographics and social context

Participants were asked to describe the parental employment condition (‘employed’ or ‘unemployed’) and highest education level (‘graduated’ or ‘not graduated’), and the perceived quality of family relationships, categorised as ‘good’ (if ‘very good’ or ‘quite good’), ‘so-so’ or ‘bad’ (if ‘not very good’ or ‘not good at all’).

Dietary behaviour

Participants were asked how frequently they consumed soft drinks. Possible answers were ‘at least once a day’, ‘at least once a week’ (i.e. from once to six times a week) and ‘hardly ever or never’ (i.e. less than once a week). Participants were also asked whether they ate at least three portions of fruits or vegetables (‘yes’ or ‘no’). These items were derived from the questionnaire of the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study (Currie et al. 2009), similarly to previous studies (Börnhorst et al. 2015).

Physical activity

The frequency of physical activity was self-reported as the number of days per week engaging in at least one hour of exercise. Answers were categorised into three groups: ‘never’, ‘one or two times a week’ and ‘three or more times a week’, following the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation for adolescents to perform at least one hour of physical activity per day, three times a week (World Health Organization 2010). Daily screen use (e.g. smartphone, computer, television or videogames) in hours was assessed through items derived from the WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (Börnhorst et al. 2015), and a dichotomous answer (less or more than five hours per day) was used for the analysis.

Bullying

Participants were queried whether they had been victims of bullying using the Italian adaptation of a questionnaire originally developed and validated by Olweus (Olweus 1996; Menesini and Giannetti 1997). Items covered physically and verbally abusive behaviour, and cyberbullying. Analyses were performed using data on presence or absence of any type of bullying victimisation in the previous year (‘yes’ or ‘no’).

Sexual behaviour

At-risk sexual behaviour was described through the lifetime number of sexual partners (‘zero or one’, ‘two’, ‘three or more’), and the age at first complete sexual intercourse (‘under 14 years old’ and ‘14 years old or more’), using the appropriate subscale of the Youth Risk Behaviour Surveillance System questionnaire (Everett et al. 1997; Pellai et al. 2002).

Distress symptoms

Perceived psychological distress was investigated through the K6 scale (Kessler et al. 2010), which contains six items evaluating self-reported feelings of hopelessness, depression, uselessness, nervousness, restlessness and feeling overwhelmed. Participants reported how often they had experienced each condition in the past 30 days on a five-point Likert scale (from 1, ‘never’, to 5, ‘always’), and scores >18 were classified as ‘high distress’. This scale showed favourable psychometric properties in both adults and adolescents, with substantial concordance with clinical evaluations (Kessler et al. 2010; Mewton et al. 2016).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics – divided by sex and survey year – were presented as absolute and relative frequency. Chi-square (χ2) test was performed to determine between-group differences regarding the data collected in the five cross-sectional observations. Given the random sampling process used, these differences were used as an estimate of the variation of the abovementioned variables across time.

For the 2018 survey data, associations between weight categories and explanatory variables were investigated by univariate multinomial regressions partitioned by sex, and they were expressed as crude relative risk ratios (RRRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) – using ‘normal weight’ as baseline class.

The null hypothesis was rejected at an alpha value <0.05. Analyses were performed using Stata 14 (StataCorp 2015).

Results

Prevalence trends for study variables

Across surveys, the percentage of students with a normal weight decreased from 85.1% in 2005 to 81.6% in 2018 (−3.5%), and overweight individuals increased from 10.3% to 13.3% (+3.0%). Conversely, underweight and obesity percentages appeared to be substantially stable in the cohorts presented, ranging between 2.0% and 3.2%, and between 2.0% and 2.9%, respectively (Fig. 1).

Boys

From 2005 to 2018, the percentage of individuals with a normal weight decreased from 82.0% to 79.0% (−3.0%), whereas overweight subjects increased from 13.8% to 16.6% (+2.9%) (see Supplementary Material). Trends for the explored variables and their tests for variation over time are shown in Table 1. Both parental education level and unemployment rates rose, and a relevant reduction in the daily consumption of soft drinks was observed (46.2% in 2011, 23.1% in 2018). Moreover, a significant increase in the number of individuals who did not engage in any physical activity was outlined (6.9% in 2011, 8.8% in 2018). To continue, there was a reduction in the percentage of people who had their sexual debut before the age of 14 (13.8% in 2005, 8.9% in 2018), the lifetime number of sexual partners significantly diminished and a significant variation in perceived distress was observed over the years. No differences were observed among the other factors analysed.

Girls

The percentage of individuals with a normal weight decreased from 87.5% in 2005 to 84.6% in 2018 (−2.9%) (see Supplementary Material). As compared to the subgroup of boys, the last survey outlined a higher percentage of underweight people (4.1% versus 1.5%), and a lower proportion of individuals with a condition of obesity (1.8% versus 2.8%) or overweight (9.5% versus 16.6%). Prevalence trends for the investigated variables are shown in Table 2. As for boys, an increasing number of individuals reported having a graduated or unemployed parent. Significant reductions were observed for daily consumption of soft drinks (37.5% in 2011, 16.6% in 2018), whereas vegetables consumption did not vary. Differently from the subgroup of boys, relevant variations were found for bullying victimisation (20.7% in 2008, 27.6% in 2018), and the percentage of girls doing physical activity at least three times a week rose significantly. No significant variations were observed in the early initiation of sexual activity or the total number of partners – a differing trend as compared to the subgroup of boys. On the contrary, a worsening quality of family relationships was detected, and perceived psychological distress increased over time.

Factors clustering with weight alterations

Multinomial logistic analyses outlined different roles for the abovementioned variables, with some of them exhibiting sex-specific patterns (Table 3).

Boys

Variables associated with underweight were having an unemployed parent, at least five hours of daily screen use, bullying victimisation, first sexual intercourse before 14 years, three or more sexual partners and problematic family relationships. On the contrary, doing physical activity more than twice a week, and a moderate soft drinks consumption (i.e. more than once a week but not every day) turned out to be protective factors. Factors associated with overweight were having an unemployed father, reduced use of soft drinks, eating at least three portions of fruit or vegetables per day, an early sexual debut and experiencing high distress. On the contrary, having a graduated parent proved to be a protective factor. To conclude, factors clustering with obesity were having an unemployed parent, using screens for at least five hours a day, early initiation of sexual activity, a higher number of partners, being bullied, bad family relationships and experiencing psychological distress. Conversely, protective factors were a higher parental education level and doing physical activity at least once a week.

Girls

Factors associated with underweight were having an unemployed father and deteriorated family relationships. Conversely, a reduced consumption of soft drinks (as compared to daily use) and doing physical activity more than three times a week had a protective value. Factors associated with overweight were a lower consumption of soft drinks, bullying victimisation and deteriorated family relationships. On the contrary, protective factors were the presence of a graduate as the highest familiar qualification and practicing physical activity at least three times a week. Factors clustering with obesity were parental unemployment, eating at least three portions of fruit or vegetables a day, being bullied, engaging in sexual activity before 14 years and reporting higher levels of distress. In contrast, having a graduated parent and doing frequent physical activity were outlined as protective factors. Because no woman suffering from obesity reported screen use for at least five hours a day, the RRR for this variable could not be esteemed.

Discussion

The present study attempted to elucidate the association of several socioeconomic and behavioural factors with underweight and overweight conditions. Furthermore, this is one of the few studies which provided a comprehensive description of weight pattern changes across two decades in representative samples of adolescents from a Western country.

First, potentially relevant increases in the prevalence of overweight among both boys and girls were detected – in line with the Italian and European overweight data (Rokholm et al. 2010) – but the rising percentage of underweight girls warrants specific attention considering the emergence of eating disorders in this population (Klump et al. 2009). Concomitantly, significant variations were outlined regarding family environment, eating behaviour, interpersonal factors and psychological distress, including sex-specific patterns for some of the variables presented, thus warranting continuous monitoring of these conditions.

Regarding family environment, the percentages of graduated parents and unemployment increased across time. In this sense, a higher familiar qualification turned out to be protective against overweight and obesity among adolescents of both sexes, in line with previous studies highlighting a protective value of parental education against overweight (Apouey and Geoffard 2016). Similarly, the association between parental unemployment and pathological weight confirmed the relevance of socioeconomic factors, in line with the higher prevalence of overweight among less affluent families of most Central and Western Europe countries (Due et al. 2009). This phenomenon should most probably be seen considering the relationship between a reduced purchasing power and the quality of eating habits (Drewnowski and Specter 2004; Milicic and DeCicca 2017). In this perspective, the outlined prevalence trends could be interpreted as a consequence of the widespread economic crisis of 2008. For this reason, even if the present study showed a progressive reduction in the consumption of soft drinks, the abovementioned recent economic trends require careful monitoring of this proxy of unhealthy eating behaviour and social disadvantage (Costa et al. 2018). Regarding the paradoxical association between fruit and vegetables consumption and overweight, it is possible that individuals with pathological weight may prefer healthier dietary choices, or that they may have produced a distorted self-report of eating habits: considering the cross-sectional design of these associations, further investigations are necessary to clarify this ambiguity.

Intensive screen use was associated with both underweight and obesity among male adolescents. From one side, screen-based activities may express sedentary attitudes which result in both loss of muscle mass and increased body fat; on the other hand, it has already been suggested that television and videogames use may cluster with unhealthy eating habits (Pearson and Biddle 2011). More in general, excessive screen use might underlie the presence of other dysfunctional behaviour, which can exert an impact on physical and mental health (Hoare et al. 2016), and current cultural trends are likely to emphasise the importance of this factor in the future.

Physical activity confirmed to have a protective role against both excessive and reduced body weight (Owen et al. 2010). Indeed, exercising once or twice a week was found to be inversely associated with obesity, reinforcing previous observations on the importance of physical activity during adolescence for physical and mental health (Holbrook et al. 2020).

As well as for other factors clustering with pathological weight, bullying victimisation – which proved to be increasing among young women – was associated with underweight and obesity among boys, and overweight among girls. As for most of the abovementioned variables, the relationship between pathological weight and bullying is complex and probably bidirectional. In fact, it is more likely for individuals with obesity to become victims of a bully (van Geel et al. 2014), but the reverse phenomenon might also play a role: indeed, cohort studies showed that people who were bullied at an early age were exposed to a greater risk of developing excessive weight (Baldwin et al. 2016). It can be speculated that the basis of this association is the increased risk of developing pathological eating behaviour for victims of appearance-related teasing, with solid evidence for emotional eating (Lie et al. 2019). On the other hand, victimisation based on physical appearance has already been found to involve underweight individuals (Lian et al. 2018).

The present study showed a decreasing proportion of boys who reported having had sex before the age of 14 and more than three sexual partners, whereas these data remained stable among girls. These results are in line with previous studies, according to which the proportion of sexually experienced adolescents declined over time (Santelli et al. 2000; Eaton et al. 2011). The association between dysregulated sexuality and weight problems may reflect the presence of common underlying factors – for example, adverse childhood experiences – as seen in a clinical sample of subjects suffering from eating disorders (Castellini et al. 2020). Among girls, another explanation of the association could be that a higher proportion of fat mass is associated with a lower age at menarche, which in turn is related to an earlier sexual debut (James et al. 2012).

A low quality of family relationships was found to be associated with pathological weight in both sexes, confirming that eating behaviour and body weight in the offspring are influenced by the emotional climate at home (Wertheim et al. 1992; Cromley et al. 2010). Indeed, lower levels of family cohesion already proved to be associated with overeating (Cromley et al. 2010), and with behaviour aimed at losing weight (Wertheim et al. 1992).

More in general, the present survey confirmed that overweight is associated with higher levels of psychological distress, in accordance with previous studies outlining poorer mental health among these individuals, and various explanations for this likely bidirectional association can be given (Needham and Crosnoe 2005; Hoare et al. 2016). Most probably, these findings should be seen and discussed in the light of each of the abovementioned environmental and behavioural sources of distress.

Some limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, adolescents tend to under-report weight and to over-report height (Chau et al. 2013). For this reason, the proportion of subjects with pathological weight may be underestimated. Second, the utilisation of a self-reported questionnaire may have led to a distorted report of some variables, as those which may be associated with feelings of shame in the respondents (e.g. unemployment rates of parents, which are considerably low as compared to national data; and unhealthy eating behaviour, as outlined by the unexpected association between soft drinks use and normal weight). Third, the broad categories used for the assessment of variables may have resulted in reduced variance, and the intrinsic characteristics of this evaluation necessarily provided a significant approximation of the complex phenomena investigated. In addition, even if random sampling minimises the risk of biases related to the value of the present findings, it is relevant to underline that putative prevalence variations were indirectly esteemed through between-group comparisons of independent cross-sectional observations. To conclude, the study design does not allow causal interpretation of the data presented, given the cross-sectional design for each cohort.

Conclusions and clinical implications

The increased number of adolescents with weight alterations deserves a close re-evaluation in the coming years. This epidemiological study confirmed that complex patterns of social, environmental, and behavioural changes intervene in determining the epidemiology of pathological weight. Considering that the variables presented depend on the economic status of the families, it is possible to hypothesise a relevant impact of socioeconomic crises on the physical and mental health of adolescents. Indeed, recent variations in the prevalence of these factors outline priorities for close monitoring and future interventions, which should not only focus on well-established risk factors (such as eating behaviour and sedentary lifestyle) but also on emerging social and interpersonal factors.

Availability of data and material

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Code availability

The code underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Abarca-Gómez L, Abdeen ZA, Hamid ZA et al (2017) Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 390:2627–2642. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3

Apouey BH, Geoffard P-Y (2016) Parents’ education and child body weight in France: the trajectory of the gradient in the early years. Econ Hum Biol 20:70–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2015.10.005

Bacchini D, Licenziati MR, Garrasi A et al (2015) Bullying and victimization in overweight and obese outpatient children and adolescents: an Italian multicentric study. PLoS One 10:e0142715. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142715

Baldwin JR, Arseneault L, Odgers C et al (2016) Childhood bullying victimization and overweight in young adulthood: a cohort study. Psychosom Med 78:1094–1103. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000388

Börnhorst C, Wijnhoven TMA, Kunešová M et al (2015) WHO European childhood obesity surveillance initiative: associations between sleep duration, screen time and food consumption frequencies. BMC Public Health 15:442. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1793-3

Boyer BP, Nelson JA, Holub SC (2015) Childhood body mass index trajectories predicting cardiovascular risk in adolescence. J Adolesc Health 56:599–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.01.006

Castellini G, D’Anna G, Rossi E, et al (2020) Dysregulated sexuality in women with eating disorders: the role of childhood traumatic experiences. J Sex Marital Ther 46:793–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2020.1822484

Chau N, Chau K, Mayet A et al (2013) Self-reporting and measurement of body mass index in adolescents: refusals and validity, and the possible role of socioeconomic and health-related factors. BMC Public Health 13:815. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-815

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH (2000) Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 320:1240. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240

Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D, Jackson AA (2007) Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: international survey. BMJ 335:194. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39238.399444.55

Costa CS, Del-Ponte B, Assunção MCF, Santos IS (2018) Consumption of ultra-processed foods and body fat during childhood and adolescence: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr 21:148–159. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017001331

Cromley T, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Boutelle KN (2010) Parent and family associations with weight-related behaviors and cognitions among overweight adolescents. J Adolesc Health 47:263–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.009

Currie C, Nic Gabhainn S, Godeau E (2009) The health behaviour in school-aged children: WHO collaborative cross-national (HBSC) study: origins, concept, history and development 1982-2008. Int J Public Health 54(Suppl 2):131–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-5404-x

Danielsen YS, Stormark KM, Nordhus IH et al (2012) Factors associated with low self-esteem in children with overweight. Obes Facts 5:722–733. https://doi.org/10.1159/000338333

Desai RA, Manley M, Desai MM, Potenza MN (2009) Gender differences in the association between body mass index and psychopathology. CNS Spectr 14:372–383. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852900023026

Devaux M, Sassi F (2013) Social inequalities in obesity and overweight in 11 OECD countries. Eur J Pub Health 23:464–469. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckr058

Drewnowski A, Specter SE (2004) Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am J Clin Nutr 79:6–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.1.6

Due P, Damsgaard MT, Rasmussen M et al (2009) Socioeconomic position, macroeconomic environment and overweight among adolescents in 35 countries. Int J Obes 33:1084–1093. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2009.128

Eaton DK, Lowry R, Brener ND et al (2011) Trends in human immunodeficiency virus- and sexually transmitted disease-related risk behaviors among U.S. high school students, 1991-2009. Am J Prev Med 40:427–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.010

Etile F (2014) Education policies and health inequalities: evidence from changes in the distribution of body mass index in France, 1981–2003. Econ Hum Biol 13:46–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2013.01.002

Everett SA, Kann L, McReynolds L (1997) The youth risk behavior surveillance system: policy and program applications. J Sch Health 67:333–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.1997.tb03468.x

Gebremariam MK, Altenburg TM, Lakerveld J et al (2015) Associations between socioeconomic position and correlates of sedentary behaviour among youth: a systematic review. Obes Rev 16:988–1000. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12314

Gordon LP, Diaz A, Soghomonian C et al (2016) Increased body mass index associated with increased risky sexual behaviors. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 29:42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2015.06.003

Gustafson TB, Sarwer DB (2004) Childhood sexual abuse and obesity. Obes Rev 5:129–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00145.x

Hoare E, Milton K, Foster C, Allender S (2016) The associations between sedentary behaviour and mental health among adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 13:108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0432-4

Holbrook HM, Voller F, Castellini G et al (2020) Sport participation moderates association between bullying and depressive symptoms in Italian adolescents. J Affect Disord 271:33–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.142

Homma Y, Wang N, Saewyc E, Kishor N (2012) The relationship between sexual abuse and risky sexual behavior among adolescent boys: a meta-analysis. J Adolesc Health 51:18–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.032

James J, Ellis BJ, Schlomer GL, Garber J (2012) Sex-specific pathways to early puberty, sexual debut, and sexual risk taking: tests of an integrated evolutionary-developmental model. Dev Psychol 48:687–702. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026427

Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ et al (2010) Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO world mental health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 19:4–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.310

Klump KL, Bulik CM, Kaye WH et al (2009) Academy for eating disorders position paper: eating disorders are serious mental illnesses. Int J Eat Disord 42:97–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20589

Lian Q, Su Q, Li R et al (2018) The association between chronic bullying victimization with weight status and body self-image: a cross-national study in 39 countries. PeerJ 6:e4330. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4330

Lie SØ, Rø Ø, Bang L (2019) Is bullying and teasing associated with eating disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord 52:497–514. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23035

Matthiessen J, Stockmarr A, Biltoft-Jensen A et al (2014) Trends in overweight and obesity in Danish children and adolescents: 2000-2008 – exploring changes according to parental education. Scand J Public Health 42:385–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494813520356

Menesini E, Giannetti E (1997) Il questionario sulle prepotenze per la popolazione italiana: problemi teorici e metodologici. In: “Il bullismo in Italia”. Giunti, Firenze

Mewton L, Kessler RC, Slade T et al (2016) The psychometric properties of the Kessler psychological distress scale (K6) in a general population sample of adolescents. Psychol Assess 28:1232–1242. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000239

Milicic S, DeCicca P (2017) The impact of economic conditions on healthy dietary intake: evidence from fluctuations in Canadian unemployment rates. J Nutr Educ Behav 49:632–638.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2017.06.010

Needham BL, Crosnoe R (2005) Overweight status and depressive symptoms during adolescence. J Adolesc Health 36:48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.015

Olweus, D (1996) The revised Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Research Center for Health Promotion (HEMIL Center), Bergen

Owen N, Sparling PB, Healy GN et al (2010) Sedentary behavior: emerging evidence for a new health risk. Mayo Clin Proc 85:1138–1141. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0444

Pearson N, Biddle SJH (2011) Sedentary behavior and dietary intake in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 41:178–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.002

Pellai A, Brizzi L, Curci R et al (2002) Valutazione del rischio di disturbi del comportamento alimentare negli adolescenti del Nord Italia. Risultati di uno studio multicentrico. Minerva Pediatr 54:139–145

Puhl R, Suh Y (2015) Health consequences of weight stigma: implications for obesity prevention and treatment. Curr Obes Rep 4:182–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-015-0153-z

Rokholm B, Baker JL, Sørensen TIA (2010) The levelling off of the obesity epidemic since the year 1999 – a review of evidence and perspectives. Obes Rev 11:835–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00810.x

Santelli JS, Lindberg LD, Abma J et al (2000) Adolescent sexual behavior: estimates and trends from four nationally representative surveys. Fam Plan Perspect 32:156–194. https://doi.org/10.2307/2648232

StataCorp (2015) Stata statistical software: release 14. StataCorp LP, College Station, TX

van Geel M, Vedder P, Tanilon J (2014) Are overweight and obese youths more often bullied by their peers? A meta-analysis on the relation between weight status and bullying. Int J Obes 38:1263–1267. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.117

Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ, Maude D et al (1992) Psychosocial predictors of weight loss behaviors and binge eating in adolescent girls and boys. Int J Eat Disord 12:151–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(199209)12:2<151::AID-EAT2260120205>3.0.CO;2-G

World Health Organization (2010) Global recommendations on physical activity for health. World Health Organization, Geneva https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241599979. Accessed 24 May 2021

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to the Regional Board of Studies (Ufficio Scolastico Regionale Toscana) for their effort in supporting the organisation of the present work and in data collection.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Firenze within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This work was entirely funded by Agenzia Regionale di Sanità (ARS) Toscana through its ordinary budget from Regione Toscana (Tuscany Regional Administration). ARS contributed to study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: GC, FV, CS; Data curation: GD, ER, ML, AB, FI; Formal analysis: EC, ML; Investigation: GC, GD, FV, CS, VR; Methodology: GC, ML, AB, FI; Project administration: FV, CS; Writing – original draft: GD, ER, EC; Writing – review & editing: GC, GD, FV, CS, VR.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the sponsoring institution, and it was performed in accordance with the ethical standards contained in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent to participate and consent to publication

Written informed consent was collected from participants, and from their parents or legal tutor (for individuals younger than 18 years old). This included the consent to data publication in aggregate form.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Fig. 1

Weight categories for the subgroup of boys (panel a) and girls (panel b), divided by survey year. (PNG 19893 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Castellini, G., D’Anna, G., Rossi, E. et al. Body weight trends in adolescents of Central Italy across 13 years: social, behavioural, and psychological correlates. J Public Health (Berl.) 31, 1165–1175 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01627-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01627-6