Abstract

Aim

One of the public health objectives of the Swedish and Danish alcohol policies is to reduce harm to individuals from the risky consumption of alcohol. In furtherance of this objective, it is interesting to research the purchasing and consumption patterns of drinkers, with a particular focus on clarifying the purchasing behavior of heavy drinkers relative to moderate and light drinkers. Thus, this article examines demand for alcoholic beverages in Denmark and Sweden.

Subjects and methods

Since there are significant differences in alcohol policy in Denmark and Sweden, it is interesting to study a comparative analysis of consumer behavior. Our study included a randomly drawn sample of the alcohol-buying population in both countries. A proportional odds model was applied to capture the natural ordering of dependent variables and any inherent nonlinearities.

Results

The findings show that individual demand for alcoholic beverages depends on economic, regional, and socio-demographic variables but that there is also a heterogeneity in consumer response to alcohol consumption under competition and monopoly.

Conclusion

This study provides some evidence and support to the notion that people can generally be characterized by certain factors associated with alcohol demand. This information can help policymakers when they discuss concepts related to public health issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Agresti A (2007) An introduction to categorical data analysis, 2nd edn. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY

Akerlof GA (1970) The market for lemons: quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Q J Econ 84(3):488–500

Anderson P, Baumberg B (2006) Alcohol in Europe: a public health perspective. London: Institute of Alcohol Studies. European Commission (OIL), Luxembourg, ISBN 92-79-02241-5

Assari S, Moghani Lankarani M (2016) Education and alcohol consumption among older Americans; black-white differences. Front Public Health 4:67

Batty GD, Lewars H, Emslie C, Benzeval M, Hunt K (2008) Problem drinking and exceeding guidelines for 'sensible' alcohol consumption in Scottish men: associations with life course socioeconomic disadvantage in a population-based cohort study. BMC Public Health 8:302

Berggren F (1997) Essays on the demand for alcohol in Sweden: review and applied demand studies, Lund Economic Studies no. 71., Lund University

Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, Williams DR, Jackson JS (2001) Neighborhood disadvantage, stress, and drug use among adults. J Health Soc Behav 42(2):151–165

Borders TF, Booth BM (2007) Rural, suburban, and urban variations in alcohol consumption in the United States: findings from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Rural Health 23(4):314–321

Bränström R, Andréasson S (2008) Regional differences in alcohol consumption, alcohol addiction and drug use among Swedish adults. Scand J Public Healt 36(5):493–503

Brinkley GL (1999) The causal relationship between socioeconomic factors and alcohol consumption: a Granger-causality time series analysis, 1950-1993. J Stud Alcohol 60:759–768

Britton A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Benzeval M, Ku D, Bell S (2015) Life course trajectories of alcohol consumption in the United Kingdom using longitudinal data from nine cohort studies. BMC Med 13:47

Bryden A, Roberts B, Petticrew M, McKee M (2013) A systematic review of the influence of community level social factors on alcohol use. Health Place 21:70–85

Capuano AW (2012) Constrained ordinal models with application in occupational and environments health. Ph.D dissertation, University of Iowa

Cerdá M, Johnson-Lawrence VD, Galea S (2011) Lifetime income patterns and alcohol consumption: investigating the association between long- and short-term income trajectories and drinking. Soc Sci Med 73(8):1178–1185

Chan CK, Leung J, Quinn C, Kelly AB, Connor JP, Weier M, Hall WD (2016) Rural and urban differences in adolescent alcohol use, alcohol supply, and parental drinking. J Rural Health 32(3):280–286

Cook P, Moore M (2001) Environment and persistence in youthful drinking patterns. In: Gruber J (ed) Risky behavior among youths: an economic analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 375–337

Crum RM, Helzer JE, Anthony JC (1993a) Level of education and alcohol abuse and dependence in adulthood: a further inquiry. Am J Public Health 83(6):830–837

Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF (1993b) Population-based norms for the mini-mental state examination by age and educational level. JAMA 12 269(18):2386–2391

Dawson DA, Hingson RW, Grant BF (2011) Epidemiology of alcohol use, abuse and dependence. In: Tsuang MT, Tohen M, Jones PB (eds) textbook in psychiatric epidemiology, 3rd edn. Wiley, Chichester

Dixon MA, Chartier KG (2016) Alcohol use patterns among urban and rural residents’ demographic and social influences. Alcohol Res 38(1):69–77

Droomers M, Schrijvers CT, Stronks K, van de Mheen D, Mackenbach JP (1999) Educational differences in excessive alcohol consumption: the role of psychosocial and material stressors. Prev Med 29(1):1–10

Gallet CA (2007) The demand for alcohol: a meta-analysis of elasticities. The Aust J Agric Resour Econ 51(2):121–135

Halldin J (1984) Prevalence of mental disorder in an urban population in central Sweden with a follow up of mortality. Thesis. Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, Stockholm

Higuchi S, Parrish KM, Dufour MC, Towle LH, Harford TC (1994) Relationship between age and drinking patterns and drinking problems among Japanese, Japanese-Americans, and Caucasians. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 18(2):305–310

Hu X, Stowe CJ (2013) The effect of income on health choices: physical activity and alcohol use, 2013 annual meeting, August 4-6, Washington, DC 149616. Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, Washington DC

Huckle T, Quan You R, Casswell S (2010) Socio-economic status predicts drinking patterns but not alcohol-related consequences independently. Addiction 105(7):1192–1202

Huerta MC, Borgonovi F (2010) Education, alcohol use and abuse among young adults in Britain. Soc Sci Med 71(1):143–151

Johnson W, Kyvik KO, Mortensen EL, Skytthe A, Battylan GD, Deary J (2011) Does education confer a culture of healthy behavior? Smoking and drinking patterns in Danish twins. Am J Epidemio 173(1):55–63

Jones SC, Magee CA (2011) Exposure to alcohol advertising and alcohol consumption among Australian adolescents. Alcohol and Alcoholism 46(5):630–637

Kendler KS, Larsson Lönn S, Salvatore J, Sundquist J, Sundquist K (2016) Effect of marriage on risk for onset of alcohol use disorder: a longitudinal and co-relative analysis in a Swedish national sample. Am J Psychiatry 173:911–918

Kerr WC, Fillmore KM, Bostrom A (2002) Stability of alcohol consumption over time: evidence from three longitudinal surveys from the United States. J Stud Alcohol 63:325–333

Leonard KE, Rothbard JC (1999) Alcohol and the marriage effect. J Stud Alcohol Suppl 13:139–146

Long JS (1997) Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA

McCullagh P (1980) Regression models for ordinal data. J R Stat Soc B 42(2):109–142

Milgrom P, Roberts J (1986) Price and advertising signals of product quality. J Polit Econ 94(4):796–821

Morrison C (2015) Exposure to alcohol outlets in rural towns. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39(1):73–78

National Rural Health Alliance (2014) Alcohol use in rural Australia, Victoria, Australia, Victoria

Nelson JP, Young DJ (2001) Do advertising bans work? An international comparison. Int J Advert 20(3):273–296

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt L (2006) Possible contributors to the gender differences in alcohol use and problems. J Gen Psychol 133(4):357–374

Parry CDH, Plüddemann A, Steyn K, Bradshaw D, Norman R, Laubscher R (2005) Alcohol use in South Africa: findings from the first demographic and health survey (1998). J Stud Alcohol 66:91–97

Penttilä R, Österberg E (2017) Information on the Nordic alcohol market. National Institute for health and welfare (THL), Helsinki

Plant M, Miller P, Plant M, Kuntsche S, Gmel G, Ahlstrom S (2008) Marriage, cohabitation and alcohol consumption in young adults: an international exploration. J Subst Use 13(2):83–98

Rao AR, Monroe KB (1988) The moderating effect of prior knowledge on cue utilization in product evaluations. J Consum Res 15(2):253–264

Rosenquist JN, Murabito J, Fowler JH, Christakisa NA (2010) The spread of alcohol consumption behavior in a large social network. Ann Intern Med 152(7):426–433

Saffer H, Dave D (2006) Alcohol advertising and alcohol consumption by adolescents. Health Econ 15(6):617–637

Saffer H, Dave D, Grossman M (2016) A behavioral economic model of alcohol advertising and price. Health Econ 25(7):816–828

Schulte MT, Ramo D, Brown SA (2009) Gender differences in factors influencing alcohol use and drinking progression among adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev 29(6):535–547

Snyder LB, Milici FF, Slater M, Sun H, Strizhakova Y (2006) Effects of alcohol advertising exposure on drinking among youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160(1):18–24

Stiving M (2000) Price-endings when prices signal quality. Manag Sci 46(12):1617–1629

The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs (2017) Alcohol consumption in Sweden. Stockholm, Sweden, Stockholm

Treno AJ, Ponicki WR, Remer LG, Gruenewald PJ (2008) Alcohol outlets, youth drinking, and self-reported ease of access to alcohol: a constraints and opportunities approach. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32(8):1372–1379

Victoria Health Promotion Foundation (2017) Brief insights drinking cultures in rural and regional settings, generation X and baby boomers. Victoria, Australia, Victoria

Wagenaar AC, Salois MJ, Komro KA (2009) Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: a meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction 104(2):179–190

Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm ND, Gmel G (2009) Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction 104(9):1487–1500

Ziebarth N, Grabka M (2009) In vino Pecunia? The association between beverage-specific drinking behavior and wages. J Labor Res 30(3):219–244

Acknowledgments

I thank two anonymous referees for their comments. Any remaining errors are my responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: Informed consent

Verbal consent was taken, i.e., the participants were verbally informed about the structure of the study and verbally agreed to participate. Information was presented to enable individuals to freely decide whether or not to participate in the process. The participants were informed about the study’s purpose and duration and assured of confidentiality and their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Proportional odds model (POM)

Since our response, i.e., the observations on our dependent variable, was a three-level ordinal variable, it is wise to consider the natural ordering to the response levels when modeling the effects of the explanatory variables on consumer behavior (Agresti 2007). Let:

and

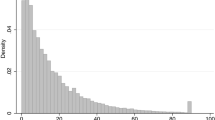

where π1(xi) is the probability of being a heavy alcohol consumer (HAC) at the ith setting of values of k explanatory variables xi = (x1i,..., xki), while π2(xi) and π3(xi) are the probabilities of being a moderate alcohol consumer (MAC) and being a low alcohol consumer (LAC), respectively. Thus, θ1(xi) and θ2(xi) represent cumulative probabilities: θ1(xi) is the probability of being an HAC, and θ2(xi) is the probability of being an MAC or even being an HAC. Let us define the two cumulative logits:

and

The first cumulative logit should be interpreted as the log odds of being an HAC compared with being an MAC or an LAC, and the second logit is the log odds of being an MAC or an HAC compared with an LAC. By assuming that the log odds are linear functions of the explanatory variables, we can write:

We maximized the log of the likelihood function to obtain maximum likelihood estimates:

subject to Eq, (5), where dhi = 1 if the ith individual gets the hth purchasing option i = 1, 2 …, n, h = 1, 2, 3 dhi = 0 otherwise.

However, this approach does not take into account the ordinal scale of the response variable. Thus, we suggest using the following, more parsimonious, model:

Hence, the effect of an explanatory variable on the log odds of being an HAC compared with being an MAC or LAC is the same as the log odds of being an MAC or HAC compared with being an LAC. Furthermore, to better grasp the consequences implied by the restriction, let x1 and x2 be two different settings of the explanatory variables. We then have the following result:

The log cumulative odds ratios are proportional to the distance between the values of the explanatory variables. This feature has also given the model its name as the POM model. However, maximizing the log of the likelihood function given by Eq. (6) subject to the constraints in Eq. (7) yields the parameter estimates of α1, α2, and β.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Irandoust, M. A non-linear approach to alcohol consumption decisions: monopoly versus competition. J Public Health (Berl.) 29, 1443–1453 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01264-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01264-5