Abstract

Before the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was scheduled to enter into force, the United States withdrew from the trade accord. Eleven other TPP signatories decided to revive the agreement, which led to the implementation of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for TPP (CPTPP). The objectives of this paper are threefold: (i) estimating economic welfare effects under alternative scenarios of the TPP/CPTPP, (ii) evaluating the extent of losses to the US from its withdrawal from TPP and expected gains from rejoining the Trans-Pacific trade accord, and (iii) examining whether the US economy would have to undergo extensive sectoral adjustments from its participation. To examine these issues, we employ a dynamic computable general equilibrium (CGE) model that incorporates agent-specific import preferences. The results suggest that the US loses an opportunity to gain approximately $100 billion per year in its long-run economic welfare by withdrawing from the TPP. However, it could recover most of its projected welfare gains by reengaging with the CPTPP. Since sectoral output adjustments in the US are relatively small, its adjustment costs from participation in the CPTPP would be limited.

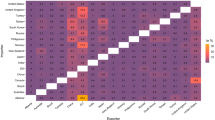

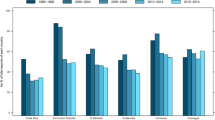

Source: model simulations

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Since only 33 days were left in 2022 when the CPTPP came into force in Malaysia, we assumed Malaysia started implementing CPTPP in 2023.

The founding members of the IPEF are Australia, Brunei, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, the US, and Vietnam.

The government is contained in consumers since the final demand includes its spending.

CPTPP7: Australia, Canada, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam. CPTPP8: CPTPP7 plus Peru. CPTPP9: CPTPP8 plus Malaysia. CPTPP13: CPTPP9 plus Brunei, Chile, Korea, and the UK.

TPP8: Australia, Canada, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore, the United States, and Vietnam. TPP9: TPP8 plus Peru. TPP10: TPP9 plus Malaysia. TPP14: TPP10 plus Brunei, Chile, Korea, and the UK.

A representative household’s utility is another welfare measure often used.

Although not reported in Table 5, percent changes in sectoral employment are similar to those in sectoral output.

References

Aguiar A, Chepeliev M, Corong E, McDougall R, van der Mensbrugghe D (2019) The GTAP data base: Version 10. J Global Econ Anal 4(1):1–27

Ahn J, Dabla-Norris E, Duval R, Hu B, Njie L (2019) Reassessing the productivity gains from trade liberalization. Rev Int Econ 27(1):130–154

Armington P (1969) A theory of demand for products distinguished by place of production. IMF Staff Pap 16:159–178

Balistreri EJ, Tarr DG (2020) Comparison of deep integration in the Melitz, Krugman and Armington models: the case of the Philippines in RCEP. Econ Model 85(C):255–271

Balistreri EJ, Tarr DG (2022) Welfare gains in the Armington, Krugman and Melitz models: comparisons grounded on gravity. Econ Inq 60(4):1681–1703

Chen N, Imbs J, Scott A (2009) The dynamics of trade and competition. J Int Econ 77:50–62

Ciuriak D, Xiao J, Dadkhah A (2017) Quantifying the comprehensive and progressive agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. East Asian Econ Rev 21(4):343–384

Deardorff AV, Stern RM (2011) The Michigan model of world production and trade. In: Stern, R.M., ed., Comparative Advantage, Growth, and the Gains from Trade and Globalization. London: World Scientific

Eichengreen B, Mehl A, Chiţu L (2021) Mars or Mercury redux: the geopolitics of bilateral trade agreements. World Econ 44(1):21–44

Ferrantino MJ, Maliszewska M, Taran S (2020) Actual and potential trade agreements in the Asia-Pacific: estimated effects. Policy Research Working Paper No. 9496, Washington, DC: World Bank

Gilbert J, Furusawa T, Scollay R (2018) The economic impact of the Trans-Pacific Partnership: what have we learned from CGE simulation? World Econ 41(3):831–865

Halpern L, Koren M, Szeidl A (2015) Imported inputs and productivity. Am Econ Rev 105(12):3660–3703

Hertel TW (ed) (1997) Global trade analysis: modeling and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hinz J (2017) The ties that bind: geopolitical motivations for economic integration. Kiel Working Paper No. 2085, Kiel Institute for the World Economy

Hummels DL, Schaur G (2013) Time as a trade barrier. Am Econ Rev 103(7):2935–2959

Ianchovichina E, McDougall R (2012) Theoretical structure of dynamic GTAP. In: Ianchovichina E, Walmsley TL (eds) Dynamic Modeling and Applications for Global Economic Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

International Monetary Fund (2022) World economic outlook database, October 2022. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund

International Trade Centre (2016) Market access map (MAcMap) tariff rates for 2016–2046 between TPP member countries under the TPP agreement

Laget E, Osnago A, Rocha N, Ruta M (2020) Deep trade agreements and global value chains. Rev Ind Organ 57(2):379–410

Lee H, Itakura K (2018) The welfare and sectoral adjustment effects of mega-regional trade agreements on ASEAN countries. J Asian Econ 55:20–32

Li C, Whalley J (2021) Effects of the comprehensive and progressive agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. World Econ 44(5):1312–1337

Liu X, Ornelas E (2014) Free trade agreements and the consolidation of democracy. Am Econ J Macroecon 6(2):29–70

Melitz MJ (2003) The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71(6):1695–1725

Minor P (2013) Time as a barrier to trade: a GTAP database of ad valorem trade time costs. ImpactEcon, Second Edition. http://mygtap.org/wpcontent/uploads/2013/12/GTAP%20Time%20Costs%20as%20a%20Barrier%20to%20Trade%20v81%202013%20R2.pdf

Petri PA, Plummer MG, Zhai F (2012) Trans-Pacific partnership and Asia-Pacific integration: a quantitative assessment. Peterson Institute of International Economics, Washington, DC

Petri PA, Plummer MG (2016) The economic effects of the TPP: new estimates. In: Cimino-Isaacs, C. & Schott, J.J., eds., Trans-Pacific Partnership: An Assessment. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics

Trefler D (2004) The long and short of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement. Am Econ Rev 94(4):870–895

United Nations (2022) World population prospects: the 2022 revision. Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Population Division. New York: United Nations

United States International Trade Commission (USITC) (2016) Trans-Pacific partnership agreement: likely impact on the U.S. economy and on specific industry sectors. Washington, DC: USITC

Walmsley T, McDougall R, Ianchovichina E (2012) Welfare analysis in the dynamic GTAP model. In: Ianchovichina E, Walmsley TL (eds) Dynamic Modeling and Applications for Global Economic Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Wang Z, Mohan S, Rosen D (2009) Methodology for estimating services trade barriers. Mimeograph, Rhodium Group and Peterson Institute for International Economics

World Bank (2016) Potential macroeconomic implications of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. In: Global Economic Prospects: Spillovers amid Weak Growth. Washington, DC: World Bank

Acknowledgements

We thank James M. Brady, two anonymous reviewers, and the participants at the 24th Annual Conference on Global Economic Analysis, 23–25 June 2021, for their helpful comments.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI, Grant Numbers JP16H03616 and JP19K01677.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Itakura, K., Lee, H. Should the United States rejoin the Trans-Pacific trade deal?. Int Econ Econ Policy 20, 235–255 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-023-00559-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-023-00559-8