Abstract

This paper discusses the scope for international macroprudential policy coordination in a financially integrated world economy. It begins with a review of the transmission channels associated with, and the empirical evidence on, financial spillovers and spillbacks. Limitations of the existing literature are also identified. The potential gains associated with cross-border macroprudential coordination, dwelling on both recent analytical contributions and quantitative studies based on multi-country models with financial frictions, are then evaluated. The issue of whether coordination of macroprudential policies simultaneously requires some degree of monetary policy coordination is also discussed. The analysis focuses on the potential for policy coordination between major advanced economies and a group identified as systemically-important middle-income countries (SMICs). Next, practical ways to promote international macroprudential policy coordination are considered. Following a discussion of Basel III’s Principle of reciprocity and ways to improve it, the paper advocates a further strengthening of the current statistical, empirical and analytical work conducted by international financial institutions to evaluate, and raise awareness of, the gains from international coordination of macroprudential policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the past three decades, and despite a slowdown coinciding with the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2007–09, the degree of international financial integration has increased at a rapid pace. Changes in gross capital flows (including cross-border bank claims), gross foreign assets and liabilities, or net international asset positions, capture this process fairly well. Figure 1, for instance, shows the evolution of advanced economies’ financial exposures to a group of large middle-income countries, split into portfolio exposures and bank exposures. It shows that both types of exposures have increased substantially since the late 1990s. The rapid pace of financial globalization over the past decades has also been reflected in an over six-fold increase in the external assets and liabilities of nations as a share of GDP – despite a marked slowdown in the growth of cross-border positions in the immediate aftermath of the GFC and, more recently, disruptions to the world economy associated with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 1

Financial Exposures of Advanced Economies to Selected Middle-Income Countries1. (As a percentage of GDP)2 1Advanced economies (AEs): Australia, Canada, Denmark, euro area, Hong Kong SAR, Israel, Japan, Norway, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Middle-income countries: Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, South Africa and Turkey. 2As a percentage of advanced economies’ GDP. Sources: IMF, Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey; BIS consolidated international banking statistics; BIS locational international banking statistics; BIS calculations

Despite significant potential benefits (in terms of improved efficiency in resource allocation, for instance) financial integration and increased global interconnectedness have led to new policy challenges, associated with the amplification of shocks during turbulent times and the transmission of excess financial volatility through international capital flows.Footnote 2 Indeed, there is robust evidence that private capital flows have been a major conduit of global financial shocks across countries and have helped fuel domestic credit booms that have often ended in financial crises, especially in developing economies. But international capital flows have created macroeconomic policy challenges for advanced economies as well. In particular, it has been argued that the rest of the world’s appetite for US safe assets was an important factor behind the credit and asset price booms in the United States that fueled the subsequent financial crisis and created turmoil around the world. It is also well documented that, since the GFC, the various forms of accommodative monetary policy pursued in the United States and the euro area have exerted significant spillover effects on other countries by influencing interest rates and credit conditions around the world – irrespective, at first sight, of the nature of the exchange rate regime.Footnote 3 In response, many countries chose not to allow their currency to float freely to insulate themselves (as textbook discussions would suggest) and used instead a combination of sterilized intervention and capital controls – in effect, retreating from open capital markets, if only temporarily.Footnote 4

At the same time, there is evidence to suggest that in recent years financial market volatility in some large middle-income countries has been transmitted back, and to a greater extent, to asset prices in advanced economies and other countries. For instance, the suspension of trading after the Chinese stock market drop on January 6, 2016 affected major asset markets all over the world.Footnote 5 Thus, international spillovers have become a two-way street – with the potential to create financial instability in both directions.

International spillovers, especially those associated with monetary policy in advanced economies, can be a source of concern for another reason. Even if monetary policy is optimally tailored to macroeconomic and financial conditions in the United States or the euro area – in the sense of being geared at promoting price and output stability domestically – recipient countries may face precarious initial conditions, such as strong inflationary pressures and significant risks to financial stability (Pereira da Silva (2013)). In a context where cyclical positions are not well synchronized, international monetary policy spillovers from advanced economies could well be destabilizing for the global economy. This has led observers and policymakers in several major middle-income countries (especially Brazil and India) to issue pleas for increased policy coordination. The argument, as it is usually presented (see, for instance, Mishra and Rajan (2016) and Shin (2015)), is that policymakers in advanced economies must go beyond their national mandate – which requires taking account of the external impact of their policies only insofar as they feed back onto their own economies, through spillback effects – and explicitly account for the cross-border effects of their policy decisions when they act independently.

At the same time, in both advanced and developing economies, there has been greater reliance in recent years on national macroprudential policies, in both their structural and countercyclical dimensions.Footnote 6 As documented in a number of studies, including Akinci and Olmstead-Rumsey (2018) and Borio et al. (2021), these policies (especially those of a time-varying nature) have been fairly effective in terms of improving the resilience of national financial systems. They also appear to have helped, at least to some degree, recipient countries to insulate themselves from global financial shocks and mitigate the systemic financial risks that international capital flows may create (see Ghosh et al. (2017)). Moreover, in response to these shocks, there have also been calls for greater coordination of these policies across countries.

The purpose of this paper is to discuss, from both an analytical and policy perspective, the role of, and scope for, international macroprudential policy coordination in a financially integrated world economy. Among the issues we address are the extent to which greater coordination of macroprudential policies may help to mitigate the effects of cross-border financial spillovers and spillbacks; the magnitude of potential gains from international coordination; and the role supranational authorities may, or should, play in monitoring system-wide financial risks and promoting international coordination in the area of macroprudential regulation.

At the outset, it is important to note that even though cross-border spillovers and spillbacks may be significant, and may indeed have increased in magnitude in recent years, it does not necessarily follow that they reduce global welfare and that cooperation is prima facie welfare improving. If, for instance, the global economy is experiencing a recession, the coordinated adoption of an expansionary fiscal policy stance by a group of large countries may, through trade and financial spillovers, benefit all countries. The magnitude of this gain may actually increase with the degree to which countries are interconnected, the degree of business cycle synchronization, and the very magnitude of spillovers. Alternatively, if a country becomes more resilient to global financial shocks as a result of more active macroprudential regulation, other countries may also benefit from greater stability through less volatile trade and financial flows with that country.

However, it is also possible that national policies themselves may generate greater volatility across countries, through abrupt changes in short-term capital flows induced by fluctuations in asset prices and relative rates of return. If maintaining financial stability is a key policy objective, the propagation of financial risks through these flows may become a source of concern. These risks – which may be magnified by domestic financial market imperfections – may or may not materialize in the same manner across countries, even when they are highly integrated, because short-term capital flows are not always driven by fundamentals or because countries can be at different stages of their business and financial cycles. But to the extent that financial risks represent negative externalities that tend to increase with the magnitude of spillovers and spillbacks, which may in turn be exacerbated (through cross-country leakages) by uncoordinated national macroprudential policies, there is a case for macroprudential policy coordination.Footnote 7

We focus our analysis on major advanced economies and a group of countries that we identify as systemically-important middle-income countries (SMICs), rather than “emerging markets” – a term that, in our view, has become largely obsolete.Footnote 8 Specifically, we identify this group as consisting of eight countries: Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, and Turkey.Footnote 9 Undoubtedly, these countries differ significantly in terms of a number of “real” structural characteristics (population size, shares of savings and investment in GDP, trade composition, and so on), the nature of their exchange rate regime, and their degree of international financial integration –with China and India being significantly less financially open than the others. However, they are also relatively homogeneous in terms of the type of frictions and imperfections that characterize their financial systems, their inability to borrow in their own currency, their vulnerability to global shocks and adverse tail events, their importance for commodity markets (both as suppliers and demanders), and the spillbacks that they can potentially generate for advanced economies – either in the recent past or in the foreseeable future.

Indeed, although SMICs remain predominantly a destination, rather than a source, of global financial spillovers, the main conduit for these spillovers (capital flows) can cause a gradual accumulation of imbalances that can later result in substantial spillbacks to advanced economies (Bank for International Settlements (2016)). The fact that SMICs account for a growing share of both world GDP (from 10.6% in the late 1990s to 18.9% in 2011–15) and world exports of goods and services (from about 10% in the late 1990s to 20% in 2011–15) also creates the possibility of a trade channel through which spillback effects may occur. These features are important from the perspective of this study. Moreover, these countries have been statistically identified by the International Monetary Fund (2016a, Chapter 2; 2016c)) as generating significant spillback effects on advanced economies in recent years, especially through equity markets. Our premise therefore is that they stand to benefit the most from international coordination with major advanced economies, and vice versa. More generally, our view is that promoting global macroprudential policy coordination, especially at the high-frequency level required for conducting countercyclical policy, can best be achieved by following a two-step approach – first by fostering coordination between major advanced economies and SMICs, that is, the countries with the largest stakes in the world economy and the strongest scope for influencing each other, through both spillovers and spillbacks, and then, in a second stage, by strengthening coordination with smaller economies.Footnote 10 To a significant extent, this process may be facilitated by the fact that SMICs, through their membership of major international financial institutions, the participation of their central banks in the bi-monthly meetings of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and their prominent role in the Group of Twenty (G20), are well positioned to influence global governance issues, and possibly make coordination arrangements more sustainable.Footnote 11

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Sections 2 and 3 set the stage by reviewing the transmission channels associated with, and the empirical evidence on, global financial shocks, in terms of both financial spillovers and spillbacks. Limitations of the literature are also identified. Section 4 evaluates the potential gains from international macroprudential coordination in responding to these shocks, dwelling on both recent analytical contributions and quantitative studies based on multi-country dynamic general equilibrium models with financial market frictions.Footnote 12 We also discuss whether international coordination of macroprudential policies should simultaneously involve some degree of monetary policy coordination, given that these instruments may be complementary in promoting jointly macroeconomic stability and financial stability. Sections 5 and 6 consider preconditions for and practical ways to promote cross-border macroprudential policy coordination. Basel III’s Principle of reciprocity and ways to improve it are examined first. A broader discussion of the role of multilateral institutions is then conducted. The final section brings together the key policy lessons that can be drawn from the analysis.

2 International financial spillovers: transmission channels

Understanding the nature and magnitude of financial spillovers and how they are transmitted across borders has been the subject of a large body of literature in recent years. From the perspective of this paper, such understanding is an essential step for assessing the potential benefits of international macroprudential policy coordination. This section begins by defining the nature of financial spillovers. It then describes the various channels, direct and indirect, through which they are propagated internationally. Given the focus of our analysis, particular emphasis is put on the role of cross-border, bank-related capital flows and arbitrage incentives created by domestically focused financial regulation.

2.1 Nature of financial spillovers

Cross-border financial spillovers are commonly defined as occurrences where fluctuations in the price of an asset in one country (or region) trigger changes in the prices of the same asset or other assets in another country (or region).Footnote 13 These fluctuations can reflect both desirable effects (resulting, for instance, from the incorporation of news into forward-looking asset prices) and less desirable ones (such as the transmission of excess volatility due to market distortions and financial frictions). This definition implies that the qualitative nature, and quantitative impact, of cross-border financial spillovers depend on several dimensions: a) the type of shocks that generate fluctuations in asset prices in the source country; b) the channels, real and financial, through which shocks are transmitted internationally; c) the amplification or mitigation mechanisms operating in source and recipient countries; d) the nature of the macroeconomic and macroprudential policy regime in source and recipient countries; and e) the scope for policymakers in recipient countries to respond in a timely fashion to shocks initiated in source countries.

2.2 Transmission channels

The cross-border transmission of financial shocks (triggered, for instance, by a temporary change in short-term policy interest rates in advanced economies or a sudden shift in market risk perceptions) may occur through a number of conventional channels. In addition, and particularly important from the perspective of this paper, recent studies have emphasized the role of cross-border banking (both as a direct conduit for the propagation of financial shocks, and an amplifying mechanism for these shocks) as well as leakages associated with differences in financial regulatory regimes across countries.

2.2.1 Conventional channels

The conventional channels through which financial spillovers are typically deemed to occur involve direct and indirect changes in financial prices, cross-border balance sheet exposures, information or confidence effects (including fundamentals-driven changes in expectations), trade linkages, and policy spillovers.

Spillovers via asset prices and portfolio effects represent the standard channel through which financial shocks are transmitted across borders. When financial markets are globally integrated, changes to prices on any asset market usually translate quickly into changes in asset prices and valuations in other economies, through arbitrage and risk premia effects. For instance, when monetary policy is eased in a core country, it tends to lower longer-term yields and to raise other asset prices in that country. Through portfolio balance effects among financially interconnected economies, this may lead to capital flows to, and lower yields and higher asset prices in, other countries. In turn, this may ease financial conditions in these countries. Thus, this channel may operate solely through portfolio reallocation by investors operating in several markets across countries, that is, cross-border financial flows; it does not necessarily depend on the existence of shared fundamentals between source and recipient economies—a phenomenon referred to generally as contagion.Footnote 14,Footnote 15

Spillovers via cross-border balance sheet exposures occur through the impact of changes in asset prices on balance sheets. If collateral values depend on the behavior of asset prices (as is the case with house prices) and if changes in collateral values determine access to credit (because real estate is used to secure loans) these effects can be large and affect both consumption and investment. In addition, the wealth effects associated with changes in asset prices can affect household consumption. For banks, a balance sheet weakening can also affect lending capacity.

Spillovers through trade linkages occur even if trade flows are considerably less volatile than financial flows – thereby preventing rapid transmission and amplification of shocks through large changes or reversals. In general, trade linkages operate through an income effect and a competitiveness effect (relative price changes), which can work in opposite directions (see, for instance, Ammer et al. (2016)). To the extent that financial shocks affect income (as noted earlier), they may also be amplified through changes in trade flows. Thus, a high degree of trade openness may facilitate the propagation of financial shocks across highly integrated economies.

Spillovers through information or confidence effects occur when perception or anticipation of changes in economic fundamentals by market participants are driven by policy announcements (or expectations of them) rather than the actual realization of these changes. They are important for explaining contagion effects, in particular in the context of wake-up call effects, which happen when new information concerning a country (or region) induces markets to reassess the vulnerability of other countries (or regions).

Finally, policy spillovers occur when domestic monetary and fiscal decisions in source countries have the potential to affect foreign financial variables not only indirectly (through the channels outlined earlier) but also directly, if policymakers in recipient countries respond in the same direction. In particular, to the extent that shocks to world interest rates are accommodated by lower domestic rates, they may generate large spillover effects by inducing domestic banks to borrow more, which in turn would increase their capacity to lend. Thus, the magnitude of financial spillovers depends also on the nature of policy responses, which itself depends on the degree of financial interconnectedness.

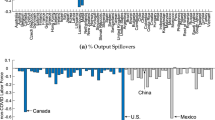

Although by their very nature trade flows tend to be less responsive to global financial shocks than capital flows, could they represent a significant transmission and amplifying channel? In particular, could they account for greater intensity of spillbacks from SMICs to advanced economies and the rest of the world? This is an important issue because (as noted in the introduction) SMICs now account for a significant share of world trade. China, specifically, accounts for a growing share of many countries’ exports, especially in the case of commodity exporters, and the impact of an increase in its spillover effects on them has grown over time (see Fig. 2).Footnote 16 And in contrast to the significant rise in exports destined to China, the share of most countries’ exports to the United States has remained stable or declined somewhat over the past 15 years. Despite this, US demand is still more important than China’s for most countries’ exports. Moreover, trade spillovers can also occur through a third country that imports intermediate inputs used in the production of its own exports. As a result, for many advanced and commodity-exporting SMICs, the indirect impact of a reduction in US imports is large relative to the direct effect. Spillovers from other major advanced economies also remain important for both advanced and systemic middle-income economies. The trade channel appears therefore to account for only a relatively small fraction of the spillback effects associated with global financial shocks.

Impact of a 10% Increase in Imports by China and the United States on Total Exports of a Given Economy or Group of Economies (Ratios for 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020, in percent). Notes: 1SMICs include Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, South Africa and Turkey; however, China is not part of that group in the top panel (only the bottom panel). The United States are not part of other AEs in the bottom panel. 2Shares of exports to China/the United States in the respective economies, multiplied by 10%. 3Direct effect of the respective economies, multiplied by the corresponding export shares. Sources: IMF, Direction of Trade Statistics; BIS calculations

More generally, the foregoing discussion suggests that financial spillovers and spillbacks are not necessarily bad if they allow new information about changes in economic fundamentals to be reflected accurately in asset prices across different countries. However, they may be undesirable when they contribute to the propagation of shocks across countries – even in the absence of significant economic linkages among them. This is the case, for instance, if portfolio re-balancing considerations induce fund managers in a core country to sell assets in a periphery country, as a result solely of constraints on exposure that they may face. Moreover, in addition to the degree of financial market integration and international portfolio diversification, the nature of policy responses, and the other factors highlighted earlier, the magnitude of financial spillovers may also depend on the cross-border activity of multinational banks and the nature of the regulatory regime in individual countries – two critical dimensions from the perspective of this study.

2.2.2 The role of global banks

Between the mid-1990s and the onset of the GFC, cross-border lending and investment activities of banks increased substantially. To a significant extent, this reflected a greater direct provision of loans and financial services by global banks, a greater share of foreign assets in banks’ trading books, and a proliferation of cross-border branches and subsidiaries, which in turn facilitated the provision of loans, investments and financial services. Indeed, as documented by Claessens and van Horen (2014), McCauley et al. (2015), and Claessens (2017), there are now large and growing networks of foreign branches and subsidiaries centered on global parent banks.Footnote 17

Figure 3 shows the classification of cross-border debt liabilities by type of counterparty (banks to banks, banks to non-banks, non-banks to banks, and non-banks to non-banks). It shows that cross-border liabilities where both creditor and debtor are banks are the largest of the four possible categories, and increased rapidly in the run-up to the GFC. Moreover, cross-border bank-to-bank funding (liabilities) can be decomposed into two distinctive forms: a) arms-length (interbank) funding that takes place between unrelated banks; and b) related (intragroup) funding that takes place in an internal capital market between global parent banks and their foreign affiliates (Reinhardt and Riddiough (2014)). Figure 4 shows that cross-border bank-to-bank liabilities also played a significant role in the expansion of domestic lending, particularly in advanced economies. At their peak, in 2007, these flows accounted for more than 25% of total private credit in recipient countries.

All Countries: Total Cross-Border Liabilities by Counterparty, 1995–2020 (Trillions of U.S. dollars). Notes: 1Cross-border claims in the form of loans and deposits of reporting countries’ banks on all countries. 2International debt securities; recipient (lender) sector is assumed to be the non-bank sector. Sources: BIS debt securities and locational banking statistics; BIS calculations

Various Country Groups: Cross-Border Bank-to-Bank Liabilities, 1995–20191. (As a percentage of private credit)2. Notes: 1Cross-border claims in the form of loans and deposits of all reporting banks in the different regions shown. 2Domestic credit to the private sector is defined as financial resources provided to the private sector by financial corporations (monetary authorities, deposit money banks and other financial corporations, such as leasing companies, money lenders, and insurance corporations, among others). This definition corresponds to the World Bank’s. 3Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, South Africa and Turkey. Sources: World Bank, World Development Indicators; BIS locational banking statistics; BIS calculations

A number of studies have documented that cross-border bank capital flows, increasingly channeled through a small group of large, global banks, have played a significant role in the international transmission of global financial shocks, including during the GFC (see, for instance, Ahrend and Goujard (2015), Buch and Goldberg (2015, 2017), and Claessens (2017)), with sizable macroeconomic and financial effects in countries where these banks operate (see Aldasoro et al. (2020)). These studies have also highlighted two main channels through which the transmission of financial risks can occur. First, if domestic lending standards are relaxed at the same time that cross-border lending is increasing (a common occurrence when banks are awash with liquidity), it can weaken the balance sheets of borrowers in recipient countries and heighten systemic risks there. Second, a global financial institution experiencing difficulties in one of the countries where it operates may fuel financial instability in the other jurisdictions where it is present. In a sense, cross-border banking may create a credit spillover channel, which may increase financial vulnerability.Footnote 18

2.2.3 Macroprudential policy leakages

It has also become increasingly clear that, in a financially integrated world, macroprudential measures taken in some countries can spill over to other countries through cross-border lending and capital flows—a phenomenon that has been referred to as policy leakages (Aiyar et al. (2014a) and Bengui and Bianchi (2018)). For instance, following a tightening of macroprudential restrictions (such as a lower loan-to-value ratio) at home, domestic banks with a regional or global presence may respond by increasing their lending abroad. If increased lending contributes to a credit boom or asset price pressures in the recipient economy or economies, a counterbalancing macroprudential response by regulators there may also be called for to mitigate heightened financial risks – especially if they are in the expansionary phase of their financial cycles.

The credit spillover channel through which cross-border arbitrage by foreign banks may occur can operate not only through direct lending to foreign-country borrowers (firms or households) but also through local lending to foreign branches, as well as a “rebooking” of loans, whereby loans are originated by subsidiaries, but then booked on the balance sheet of the parent institution. Leakages can be to banking institutions not directly covered by the specific policy instrument (Aiyar et al. (2014a)), to shadow banks (Claessens et al. (2021)), or to activities in other geographic regions (Houston et al. (2012) and McCann and O’Toole (2019)). Regardless of the precise channel through which these leakages occur, the presence of foreign branches of financial institutions that are not subject to host country regulation may undermine domestic macroprudential policies.Footnote 19 Thus, the relationship between macroprudential policies and international capital flows can go in both directions: not only are these policies responsive to capital flows, they may also affect these flows. Moreover, these interactions may generate undesirable international spillovers, thereby creating or exacerbating challenges in terms of both macroeconomic and financial stability.

Yet, this is not an unavoidable outcome. While measures aimed, for instance, at limiting risk-taking in a given country could lead to the relocation of risky financial activities to other countries, thereby making them more vulnerable to global financial shocks, macroprudential regulation may also generate positive cross-country spillovers. Indeed, if a country becomes more resilient to global financial shocks owing to macroprudential regulation, other countries may enjoy greater stability through less volatile trade and financial flows with that country. More importantly perhaps, policymakers typically have access to a range of tools to respond to macroprudential policy leakages and associated capital flows. From the perspective of an individual country, one option is for prudential authorities to avail themselves of supervisory power over both branches and subsidiaries of foreign banks, and impose their own uniform oversight (including on minimum capital requirements) on all lenders operating within the country and cross-border lending. However, if such uniform oversight is effective, the consequence may be simply to induce foreign financial institutions to shift their activities to other, less regulated countries – which may ultimately be costly for the world economy. The solution to this dilemma, as advocated by some, is harmonization of regulations across countries. But even with a high degree of coordination in setting regulatory standards – an issue we return to later on – banks facing stricter regulation in their home market may still end up taking greater risks in foreign markets, by weakening, for instance, lending standards. These effects are magnified when strict oversight in the home market is coupled with weak supervision abroad (Raman et al. (2016)).

3 Evidence on international financial spillovers

Over the last two decades, the empirical evidence on the importance of financial spillovers and spillbacks has grown significantly. Many of the recent studies have focused on the transmission of financial shocks across equity, foreign exchange, and sovereign bond markets, as well as interest rate and balance sheet effects.Footnote 20 This section begins with a brief overview of these studies. In line with our earlier analytical discussion of the transmission channels of global financial shocks, we devote more attention to the evidence on the credit spillover channel and cross-border bank flows, as well as regulatory leakages. Challenges in measuring financial spillovers are subsequently discussed.

3.1 Asset price movements and bond spreads

A common approach to measuring financial spillovers is in terms of the impact of domestic asset price movements on asset prices in other economies. Among the notable studies of this type are those of the IMF ( 2016a, 2016b, 2016c).Footnote 21 In IMF ( 2016a) spillovers are estimated using a vector autoregression (VAR) model of daily asset returns incorporating global control variables. The results suggest that over the last 20 years, spillovers of emerging market asset price shocks to equity prices and exchange rates in advanced and (other) emerging market economies have risen substantially, and now explain over a third of the variation in returns in these countries. In the years immediately following the GFC, average equity market spillovers from emerging market economies (essentially through the portfolio channel discussed earlier) increased by about 28%. These effects also differed significantly across countries; while financial market spillovers from financially open countries, such as Brazil, grew at an even faster pace, spillovers from other economies with financial markets that are less integrated internationally, such as China and India, remained quantitatively limited. For these countries, spillovers from major advanced economies are still stronger than the spillbacks that they may exert on the rest of the world.Footnote 22

Using the same methodology as the IMF, Fig. 5 shows spillovers from SMICs (as defined earlier) to an average advanced economy, with respect to exchange rate and equity returns. It suggests that, despite significant fluctuations over time, these spillovers appear to have increased on average since 2004 compared to the earlier period of 1996–2003 – especially for currency returns.

Spillover from SMICs to an Average Advanced Economy, 1996–2017. Exchange Rate and Equity Returns1 (In percentage points). 1SMICs: Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, South Africa and Turkey; Advanced economies: Australia, Canada, Denmark, the euro area, Hong Kong SAR, Israel, Japan, Norway, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. Financial market spillovers are defined as the fraction of the 12-day-ahead forecast error variance of a country’s local currency nominal equity return that can be accounted for by innovations in another country’s equity return. A similar definition holds for foreign exchange returns. Sources: Bloomberg; BIS calculations

The results of studies based on sovereign bond spreads are also consistent with a growing importance of portfolio flows as a conduit for financial spillovers. In particular, there is robust evidence of contagion – as captured by co-movements in measures of bond return risk premia that are unrelated to economic fundamentals – which reflect spillovers driven by exogenous global shifts in risk preferences.

3.2 Interest rate and balance sheet effects

Fluctuations in interest rates in major advanced economies tend to affect other countries through changes in the cost of external borrowing. For major middle-income countries, whose corporations and banks borrow heavily abroad mostly in US dollars and with little hedging – unlike other advanced economies – changes in US interest rates are a critical channel for financial spillovers. Indeed, Fig. 6 shows that SMICs have relatively high ratios of foreign currency debt to GDP. Financial spillovers may therefore amplify domestic leverage and generate large effects when borrowers face financial distress.

Selected Countries and Regions: Ratio of Total Foreign Currency Debt to GDP. (2000, 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2020, in percent). Notes: 1Total foreign currency debt of non-bank residents of the respective economies. Simple average across regions. End-of-year ratios. 2India, Indonesia, Russia and South Africa. Source: Bank for International Settlements

At the same time, the accumulation of a large stock of foreign currency-denominated debt in SMICs has heightened the potential for spillbacks to advanced economies. As noted in the introduction, low US interest rates and a depreciating US dollar boosted credit, asset prices and growth in SMICs in the aftermath of the GFC. A tightening in global financial conditions induced by prospects of higher US interest rates (as is the case at the time of this writing) could trigger a reversal of easy liquidity conditions for SMICs. Spillovers to advanced economies from SMIC holdings of specific advanced-economy assets, such as sovereign bonds, have increased (Bank for International Settlements (2016)). By contrast, spillovers to advanced economies through wealth effects from direct ownership of SMIC assets are generally small, in line with the share of SMIC assets in advanced economy portfolios.

Studies based on transmission through policy rates include Hofmann and Takáts (2015), who used quarterly panel data regressions over the period 2000–14.Footnote 23 In all their specifications, they explicitly controlled for the impact of domestic and global macroeconomic factors, as well as global financial factors. They found economically and statistically significant spillovers from the United States to a range of countries. These spillovers are present not only in short- and long-term interest rates but also in policy rates.Footnote 24

3.3 Cross-border bank flows and the credit spillover channel

Evidence on the determinants and effects of cross-border bank flows and the credit spillover channel is provided in a number of recent contributions. Studies by Cetorelli and Goldberg (2012), Bruno and Shin (2015), Tonzer (2015), Cerutti et al. (2017a) and Correa et al. (2018) focused on aggregate banking flows, whereas Reinhardt and Riddiough (2014) zeroed in on disaggregated (interbank and intragroup) flows. By and large, these studies have shown that cross-border bank capital flows are highly sensitive to changes in interest rates in advanced economies and changes in global risk perceptions, and that these changes tend to operate quickly – with potential consequences for financial stability in destination countries. Tonzer (2015), for instance, found that countries that are linked to more stable banking systems abroad through foreign borrowing or lending positions in interbank markets are significantly affected by positive spillover effects. Thus, in times of financial volatility, linkages in the banking system can contribute to the propagation of shocks. For their part, Correa et al. (2018) provided empirical support for the existence of an international portfolio rebalancing channel, whereby tighter monetary policy in source countries leads to a decrease in collateral values and the net worth of domestic borrowers, which prompts banks to substitute away from domestic credit and toward foreign credit. In a study focusing on disaggregated flows, Reinhardt and Riddiough (2014) found that intragroup funding appears to be unrelated to global or local cyclical factors, whereas interbank funding appears to respond procyclically. Thus, the composition of bank funding may also matter for the cross-border transmission of financial shocks.

3.4 Regulatory leakages and capital flows

Studies focusing on how regulatory leakages affect cross-border capital flows, which therefore act as a conduit to financial spillovers, include Houston et al. (2012), Bremus and Fratzscher et al. (2014), Aiyar et al. (2014a, 2014b), Karolyi and Taboada (2015), Reinhardt and Sowerbutts (2016), Avdjiev et al. (2017), Beirne and Friedrich (2017), Cerutti et al. (2017a), Forbes et al. (2017), Kang et al. (2017), and Takáts and Temesvary (2017).Footnote 25 Houston et al. used data aggregated at the country level and survey data on global regulations to argue that cross-border banking flows move to circumvent regulations. In the same vein, Bremus and Fratzscher found that inflows and outflows of international capital through banks around the time of the GFC responded to the stance of regulation and supervision. Using a broader sample covering the period 2000–14, Avdjiev et al. found that changes in macroprudential policy – in the form of loan-to-value limits and local-currency reserve requirements – have a significant impact on cross-border bank lending. Similar results are obtained by Takáts and Temesvary. Using also a large sample of countries and a broader variety of empirical techniques, Kang et al. found that while sectoral and liquidity based macroprudential policy measures tend to generate large cross-border bank credit spillovers, that is not the case for capital-based measures. Finally, using a sample of countries twice as large as Kang et al., Beirne and Friedrich (2017) examined the impact of eight different macroprudential policy measures on cross-border bank flows over the period 1999–2012. They found that the magnitude of cross-border spillovers associated with these measures were a function of banking sector conditions, both at home and abroad. In particular, in countries that are financially healthy (as measured by a high return on assets in the banking system), the magnitude of spillovers from the one implementing the policy measures was weaker.

Empirical evidence on cross-border spillovers associated with prudential measures has also been provided in the context of individual countries, both within the country where a macroprudential policy instrument is applied to domestic banks but not to foreign institutions competing in the same markets, and through reallocation of activity between domestic and international locations. Two important studies in that regard are those of Aiyar et al. (2014a, 2014b) for the United Kingdom, which focused on changes in capital requirements imposed by the national financial regulator (the Financial Services Authority, or FSA) on banks in the country. In the period under study, subsidiaries of foreign banks located in the United Kingdom were supervised by the FSA, whereas foreign bank branches in the country remained under the oversight of the authorities in their home country. Aiyar et al. found that when the FSA raised minimum capital requirements, there were substantial leakages, in the sense that lending shifted, from local banks and subsidiaries, to foreign-supervised branches located in the United Kingdom. They estimated the UK-wide leakages (offset) on domestic credit growth, owing only to bank branches, to be of the order of 30%. In the same vein, Reinhardt and Sowerbutts (2016) found in a broader study that cross-border leakages appear strong as well for capital requirements, especially in countries where affiliates are established as branches, but weaker for loan restriction instruments, such as loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios. Focusing on the euro area, Franch et al. (2019) found that foreign affiliates increase lending following a tightening of sector-specific capital buffers in the countries where their parent banks are located, and that bank size and liquidity play a significant role in determining the magnitude of cross-border spillovers.

Finally, some indirect evidence on cross-border spillovers is also available. Karolyi and Taboada (2015), for instance, studied how differences in bank regulation influence bank acquisition flows across countries and share price reactions to cross-border deal announcements. Using a large sample of domestic and majority cross-border deals announced between 1995 and 2012, they found evidence of a form of regulatory arbitrage, whereby acquisition flows involve acquirers from countries with stronger regulations than their targets. They also found that target and aggregate abnormal returns around deal announcements are positive and larger when acquirers come from more restrictive bank regulatory environments.

3.5 Challenges in measuring financial spillovers

The recent empirical literature discussed earlier provides convincing evidence of the increased importance of international financial market spillovers through bank and nonbank capital flows – especially those associated with portfolio reallocation or cross-border regulatory arbitrage. However, there are several dimensions in which the empirical literature can be improved. First, there is a need to examine domestic effects and international spillovers using more detailed micro-banking data, and to develop more precise measures of prudential regulation than were initially available to researchers studying cross-border spillovers. More recent databases on prudential instruments compiled by Cerutti et al. (2017b), Akinci and Olmstead-Rumsey (2018), and Alam et al. (2019), for instance, which put greater emphasis on the intensity, and not simply the direction, of macroprudential policy instrument use, are proving useful in that regard.

Second, for the most part existing econometric studies analyze the cross-border spillover effects of different shocks separately, which is useful to focus on their specific transmission mechanisms. However, in practice these shocks rarely occur in isolation, implying that there can be important interaction effects – which in turn may determine the magnitude and direction of spillover effects. For instance, shifts in global risk aversion may affect not only asset prices across countries but also world commodity prices, which may magnify interactions between trade and financial flows. An appropriate methodology is thus needed to better account for these interactions and assess their implications for cross-border spillovers and spillbacks, conditional on the nature of the macroprudential regime and the nature of global shocks.

Third, a better distinction between common shocks versus spillovers of country-specific shocks is needed. To differentiate co-movement due to spillovers from co-movement due to common and/or correlated shocks and permanent country-pair differences, spillovers are often identified with the transmission of a country-specific shock (or policy action) to other countries. To do so requires conditioning on common shocks. The challenge, however, is to separate common shocks from propagation of country-specific shocks through different channels. There may be direct spillovers (for instance, from the United States to Brazil) as well as indirect spillovers (for instance, from the United States to China, and subsequently from China to Brazil). To allow for the possibility of second-round spillovers, it is thus necessary to analyze multiple countries, or groups of countries, simultaneously. In the present setting, a basic framework would involve considering three groups -- advanced economies, SMICs (given their growing role in the world economy, as noted earlier), and the rest of the world as an aggregate.Footnote 26 One issue to be tested in that context is whether financial market spillovers between the first two groups of countries are, or have become, quantitatively stronger than real spillovers, and whether financial shocks have a disproportionate effect on cross-border real and financial spillovers during crisis periods.

4 International macroprudential policy coordination: rationale and potential gains

The scope for international macroprudential policy coordination to mitigate the adverse effects of cross-border financial spillovers and raise global welfare has been the subject of much interest in recent years. This section begins with a brief review of the link between systemic financial risks and the rationale for macroprudential regulation. The fundamental case for cross-border macroprudential policy coordination is discussed next. Quantitative evidence on the gains from cross-border macroprudential policy coordination is then examined. The section concludes with a discussion of whether monetary and macroprudential policies should be simultaneously coordinated across borders to some degree to be effective.

4.1 Systemic risks and the rationale for macroprudential regulation

The goal of macroprudential policy is commonly described as promoting financial stability by mitigating systemic risks to the financial system.Footnote 27 This contrasts with microprudential supervision, which focuses on the financial health of individual financial institutions. Systemic risks fall into four broad categories: excessive credit growth (often associated with procyclical risk-taking by financial institutions) and associated asset price inflation; excessive leveraging or deleveraging; systemic liquidity risks; and large and volatile capital flows. These risk categories often occur in combination with each other, and to varying degrees. In particular, SMICs have time and again been confronted with episodes of sudden floods in capital flows, rapid credit growth, asset price pressures, and excessive leveraging – followed by sudden stops in capital movements, which would throw the previous process into reverse (Agénor (2020, chapter 1) and Agénor et al. (2014, 2018)).

There is broad consensus that, from an operational standpoint, an aggregate that may serve as a proxy for financial stability is credit growth or changes in the credit-to-GDP ratio. On that basis, credit can be viewed as a “summary” indicator or intermediate target, which can be used to calibrate the effect of macroprudential instruments and design policies to dampen destabilizing swings in the credit cycle.Footnote 28

However, despite significant progress in recent years, no consensus has yet emerged on the transmission mechanism and effectiveness of macroprudential policies, their complementarity with microprudential policies, and the degree to which they should be coordinated with monetary policy – given that the regulatory regime may alter the monetary transmission mechanism and that changes in macroprudential instruments, through their impact on the cost and the availability of credit, can affect activity and prices.Footnote 29 Moreover, as documented in the previous section, cross-border activities of financial institutions may exacerbate challenges to macroprudential policies, with possibly unwelcome spillover effects weakening their domestic policy impact.

It is also well documented that macroprudential policy (just like many other policies) can be subject to a collective action problem, which arises from the existence of uncertainty over the benefits of macroprudential action, lobbying, and political pressure. This translates into the well-known challenge of “taking the punch bowl away just as the party gets going,” which makes the containment of financial excesses politically difficult at a national level. Thus, more often than not, the collective action problem results in too little, rather than too much, macroprudential policy response, relative to the level that would be necessary to promote financial stability or maximize national welfare. Indeed, as noted by Viñals and Nier (2014), while the benefit of macroprudential policy decisions typically accrue over time and can be difficult to measure with certainty, the cost of such decisions is often felt immediately by both borrowers and lenders. This makes it hard for financial regulators to demonstrate the will to intervene. The resulting bias in favor of inaction, or insufficiently timely and forceful action, is often compounded by lobbying and political pressure, as well as the need for domestic coordination between policymakers (say, the financial regulator and the central bank) and a lack of clarity about who is responsible for containing systemic risks. As discussed next, these problems tend to be magnified in a financially integrated world.

4.2 Fundamental case for cross-border macroprudential policy coordination

A fundamental rationale for policy coordination is the existence of externalities.Footnote 30 The literature has identified three types of externalities that might require coordination: those based on incomplete or asymmetric information, those due to asymmetries in incentives, and those due to spillovers (across agents or jurisdictions) associated with specific shocks or policies. These externalities could be either positive or negative, which implies that coordination could either prevent welfare losses or achieve welfare gains. The scope for coordination exists if there are cooperative strategies that could result in a Pareto-improving outcome.

For macroprudential policy in particular, the case for international coordination rests on the existence of cross-border financial sector externalities, related to interconnectedness of financial institutions and markets. As documented earlier, when regulatory leakages occur, the effectiveness of macroprudential policy measures applied solely to domestic financial institutions may be undermined by cross-border capital flows. Moreover, capital inflows induced by changes in financial regulation in a source country may lead to excessive credit growth and asset price pressures in recipient countries, which may only be partially mitigated by regulatory and macroeconomic policy responses in these countries. Conversely, and as noted earlier, effective domestic macroprudential policy that helps to contain systemic risks in one country may help to promote financial stability elsewhere, creating positive externalities. Indeed, lowering the probability of a financial crisis in one country through timely macroprudential policies may reduce the scope for negative trade and financial spillovers at the regional or international level. Thus, coordination is desirable when it enables countries to improve their policy trade-offs (Engel (2016)).

4.2.1 The financial trilemma

A broader case for macroprudential policy coordination among small open economies, regardless of the exchange rate regime, rests on what Claessens et al. (2010, Chapter 2), Schoenmaker (2011), and Obstfeld (2015), referred to as the financial trilemma – the fact that financial integration with global markets (with unrestricted cross-border financial flows), national control over financial supervision and regulation, and financial stability, are not all mutually compatible. That is, under a financial trilemma, a country can attain any pair of these goals: financial stability and international financial integration, financial stability and independently pursued financial policy making, or international integration and autonomous financial regulatory policies.Footnote 31 However, all three objectives cannot be achieved simultaneously.

The financial trilemma implies that, should countries choose to focus on domestic financial stability and to pursue an independent financial policy – assuming that macroprudential policies are effective in dealing with the various dimensions of financial stability issues – the goal of full integration with international financial markets cannot be achieved. National banking authorities may face significant pressures to insulate their financial systems from international competition. Such a strategy may result in financial protectionism (VanHoose (2016)). It may also imply a race to the bottom, involving unilateral capital controls (as discussed by Blanchard (2017)) or regulatory wars (as pointed out by Pereira da Silva and Chui (2017)), both of which would be detrimental to world welfare. By contrast, coordination among national regulators, which induces them to internalize the cross-border effects of their policies, may help to avoid these risks.Footnote 32 Thus, as long as obstacles to cooperative agreements can be mitigated in practice (an issue we return to later on), coordination may help to address the trade-offs highlighted by the financial trilemma.

4.2.2 Financial spillovers and international collective action problems

As noted earlier, macroprudential policy is subject to collective action problems, which often translate into insufficiently forceful and timely policy responses. In a financially integrated global economy, characterized by a high degree of cross-border interconnectedness of financial institutions and markets, these problems tend to be magnified. This is so, for instance, as a result of the first-mover disadvantage problem, which is caused by an inability of national regulators to internalize the cross-border externalities that a successful national macroprudential policy entails. In a world of integrated financial markets, a reduction of financial risks in an individual country contributes to financial stability in other countries (positive externality), whereas an inadequate response by a national regulator to home-country financial risks may increase the likelihood that financial instability may spread to other countries (negative externality). For instance, in a period of rapid credit growth and asset price pressures, a national regulator which chooses unilaterally to tighten its macroprudential policy (through, say, an across-the-board increase in capital requirements) would internalize only some of the financial stability benefits of this tightening while bearing all the potential costs in terms of reduced competitiveness of its national financial institutions.Footnote 33 Thus, no country will be willing to be the first to tighten its policies unless it believes that other countries are willing to do the same. When financial risks can be transmitted rapidly across national borders, and macroprudential measures – when applied solely to domestic financial institutions – can be promptly undermined by large capital movements across countries, there may be “too little” macroprudential policy response rather than “too much.” This may in turn reinforce biases in favor of inaction at the national level (Gaspar and Schinasi (2010) and Viñals and Nier (2014)).

Another type of collective action problem in an international context is the fact that advanced economies may claim that their mandate is narrowly defined to promote price stability and sustainable growth at home, which requires taking account of the external impact of their policies only insofar as they feed back onto their own economies. That is, only spillbacks, not spillovers per se, need to be internalized. Moreover, even when each country’s macroprudential policy is optimal at the national level, the overall combination of macroprudential policies may be suboptimal when financial cycles are not synchronized across countries or, as noted earlier, when global financial intermediaries can evade policy actions taken by national authorities through cross-border regulatory arbitrage.

What the foregoing discussion suggests is that, to reap the benefits of financial integration and ensure global financial stability, it is essential to implement measures designed to mitigate collective action problems at both the national and international levels, make regulatory arbitrage across borders more difficult (including by ensuring a high degree of international reciprocity of national macroprudential legislations, as discussed next), and establish cooperative mechanisms that can help to mitigate the financial risks that may be building up in systemic countries – including through international coordination of countercyclical macroprudential policies.Footnote 34 But before we can discuss these institutional mechanisms, we need a broader assessment of the gains from, and obstacles to, macroprudential policy coordination.

4.3 Gains from, and obstacles to, macroprudential policy coordination

To a large extent, the discussion of the gains (or lack thereof) associated with international macroprudential regulation has been based on comparing outcomes under a Nash equilibrium, in which countries act independently, and a cooperative solution, in which they act jointly. More formally, under uncoordinated policymaking, each country’s regulatory authority independently sets its policy instrument so as to minimize its own policy loss or maximize its own welfare, taking the choice of instrument of all other countries as given. The resulting policy outcomes typically fail to fully account for cross-border spillovers – that is, the real and financial externalities generated by domestic shocks, or national policy responses to these shocks, as discussed earlier. In contrast, if the regulatory authorities coordinate their choices by jointly determining their instruments with a view to minimizing a weighted sum of their policy loss functions, or maximizing a weighted sum of their national welfare functions, these spillovers would be internalized. As a consequence, and depending on the nature of the cross-border externality, coordination may enable all policymakers to attain lower policy losses or higher social welfare.

In what follows, we begin with a brief review of the analytical literature on cross-border macroprudential policy coordination. We then discuss the recent, model-based evidence on the gains associated with such coordination. We conclude by offering some suggestions for further research on measuring these gains.

4.3.1 Analytical contributions

The analytical literature on cross-border macroprudential policy coordination includes two somewhat disconnected but complementary sets of contributions – the first based on partial equilibrium models of international banking and the second (more recent) on multi-country general equilibrium macroeconomic models with financial frictions.

Partial equilibrium models of international banking

The banking and finance literature on international prudential policy coordination includes Acharya (2003), Dell’Ariccia and Marquez (2006), and Kara (2016).Footnote 35 DellAriccia and Marquez studied the incentives of national regulators to form a regulatory union in a two-country world, where a single bank from each country competes for loans in both markets in a Bertrand differentiated-products setting. Both regulators focus on the profitability of national institutions, but there is an exogenously specified asymmetry between them in terms of their preferences. The key result of the study is to show that under independent policymaking the outcome, in terms of prudential standards, could well be a race to the bottom. By contrast, a coordinated structure with higher prudential standards is more likely to emerge if: a) the impact upon profitability of prudential supervision is similar across countries; b) the weights assigned by supervisors to financial stability and banking sector competitiveness are similar; and c) the weight assigned to financial stability by supervisors is larger than that assigned to profitability and competitiveness.

Acharya (2003) focuses instead on practical issues that may impede cross-border regulatory coordination efforts. His key argument is that convergence in international capital adequacy standards cannot be effective unless it is accompanied by convergence in other aspects of financial regulation, such as bank closure policies. Thus, coordination in setting regulatory standards does not necessarily eliminate regulatory arbitrage – an important result, in light of the recent efforts to promote international cooperation (discussed later on) by the Basel Committee.

Both of the studies referred to above focused on the benefits of international coordination in financial regulation under externalities that operate through integrated loan or deposit markets in stable times. In contrast, Kara (2016) focused on pecuniary externalities between national financial markets that operate through asset markets and asset prices during times of distress.Footnote 36 In his model, banks invest in a single country and are therefore regulated only by their home supervisor – although they interact with each other in global asset markets. Systemic risk in international financial markets arises as banks experience correlated liquidity shocks, and financial amplification effects are triggered by fire sales. Regulators act simultaneously and choose the regulatory standard – a minimum capital ratio requirement, which is macroprudential in nature because it is motivated by systemic externalities – for banks in their own country. His key result is that regulation levels in the two countries are strategic substitutes: if one regulator tightens the standards in its jurisdiction, the other regulator optimally loosens its own standards. This follows from the fact that macroprudential regulation in an international context – or, more accurately, the global financial stability that it helps to promote – is fundamentally a public good. Moreover, Kara showed that the capital adequacy ratio in the non-cooperative equilibrium is inefficiently low compared to the ratio that a central regulator would choose. The key reason is that although national regulators internalize the positive effect of tighter capital requirements on asset prices, they have an incentive to free ride on regulations in the other country. Therefore, in a symmetric world, and if a binding commitment mechanism can be implemented, both countries can improve their own welfare by delegating regulatory oversight to a common regulator. However, as discussed further later on, the incentive to renege on cooperative agreements remains a key concern in practice.

Another branch of the literature considers the regulation of a multinational bank that operates across countries. Dalen and Olsen (2003) and Holthausen and Rønde (2004), for instance, focused on the tension between home and host country regulators of a global bank where informational asymmetries are the driving force of regulatory competition. In particular, Holthausen and Rønde examined issues related to information exchange between supervisory authorities, and concluded that centralization of the supervisory process within a supranational authority can yield welfare-improving bank-closure policies.

The banking and finance literature on international macroprudential policy coordination sheds useful light on a number of issues – including the structure of banking markets across countries and the objectives of financial regulators. However, the partial equilibrium nature of these models also means that they are not well suited for a full assessment of the policy or welfare gains associated with international macroprudential coordination – whether in its structural or countercyclical dimensions. To that end, general equilibrium macroeconomic models, which capture the various channels through macroprudential policies operate, are better suited.

Macroeconomic models

Recent analytical contributions on the international coordination of macroprudential policies from a macroeconomic perspective include Korinek (2014), Bengui (2014), and Jeanne (2014). Korinek showed that international cooperation is not warranted if small countries can use prudential capital controls to respond to domestic externalities. However, as noted earlier unilateral capital controls could trigger a race to the bottom, which would be detrimental to world welfare. Bengui studied the scope for international coordination in a model with public liquidity provision. He found that the noncooperative equilibrium between national regulators leads (in standard fashion) to an inefficiently low level of regulation, as national regulators do not internalize the benefits of their country’s provision of liquidity to the rest of the world. By contrast, Jeanne analyzed the scope for international coordination in a model where both domestic macroprudential policies and prudential capital controls generate international spillovers through their impact on capital flows. The uncoordinated use of macroprudential policies may lead to a “capital war” that depresses global interest rates. However, international coordination of macroprudential policies is not warranted, unless there is unemployment in some countries, or one part of the world is in a liquidity trap, while the rest of the world accumulates reserves for prudential reasons.

Obstacles to policy coordination

The banking-based and macro-based analytical literature reviewed earlier is somewhat mixed, in the sense that it suggests that coordinated macroprudential policies can potentially offer significant gains, even though this is not necessarily the case. Moreover, even if gains do exist, achieving and maintaining coordinated policies across countries in pursuit of these gains may prove difficult in practice.

First, suppose that a cooperative outcome can indeed be achieved, and that regulators have agreed to coordinate; each of them almost invariably has an incentive to cheat. Indeed, once one of the countries’ regulators has set its instrument at the agreed level, the others typically can set their own instrument at a different value and attain an even lower policy loss or higher welfare. As in standard game theory models, this incentive is stronger the smaller the perceived ex post cost of reneging on a cooperative agreement.

Second, cooperative solutions may be inefficient in the presence of third-party effects: in a policy game with three or more players, the welfare contribution of a subgroup coalition generally cannot be determined a priori, and it is very possible that policy coordination may worsen welfare (see Rogoff (1985) and Cai and McKibbin (2013)). This is important because, as discussed next, recent empirical contributions have generally been based on two-country models, in which a “core country” (which can be interpreted as an aggregate of major advanced economies) and a “periphery country” (which can be interpreted as the group of SMICs identified earlier) operate. However, while a two-country (or two-region) structure may be appropriate to generate analytical insights, as well as broad estimates of the gains from coordination, it does not account for the fact that in practice these groups are not homogeneous and face coordination issues of their own. Among advanced economies, for instance, these issues are equally important between the United States, Japan, and the euro area – even though these countries have in the past cooperated sporadically, often in the context of emergency macroeconomic policy responses to heightened risks to the world economy. This issue is even more problematic in the case of SMICs, given their historical record (or lack thereof) in that area.

Third, simple theoretical models assume that regulators across countries have the same targets and/or common national preferences, whereas in practice supervisory authorities may place diverging weights on similar goals or seek different objectives (see VanHoose (2016)). Fourth, theoretical models often assume that different countries share the same view of the world; however, in practice they often have fundamentally different perspectives on how the world economy operates. Thus, even well-intentioned regulators may not be able to carry on a coherent discussion of the potential gains from coordination – which involves assessing the costs and benefits of alternative policy choices – and how to achieve them. Indeed, as shown by Frankel and Rockett (1988) in the context of the debate on monetary policy coordination, if models are incorrect international coordination could worsen outcomes (by moving policies in the wrong direction) instead of improving them. Moreover, model perceptions could be endogenous with respect to individual country interests.Footnote 37 These problems are compounded if one thinks of policy coordination in terms of countercyclical responses (as opposed to permanent, or structural, settings of macroprudential policy instruments) because agreement on the origin and nature of shocks (common or idiosyncratic, permanent or transitory, and so on) also matters.

For all these reasons, maintaining a macroprudential policy coordination agreement is likely to be challenging in practice – even when mutual net gains from such coordination are potentially large.Footnote 38 A common response to the first challenge to maintaining coordinated policies across countries is to ensure that appropriate and credible sanctions are in place to eliminate the temptation to renege. To address the fourth challenge, a possible response might be for countries to entrust an assessment of the origin and nature of global shocks, and the need for a coordinated international response, to a group of multilateral institutions – in effect, a group of “honest brokers.” This could help not only to address the issue of model uncertainty and the magnitude of policy gains, but also to alleviate some of the collective action problems discussed earlier – inertia in policymakers’ reaction and the disadvantage of moving first –which combine to prevent a timely response to financial risks. This issue is further discussed later on.

4.3.2 Quantifying the gains from cross-border coordination

The early empirical literature on the gains from international monetary policy coordination, largely based on multi-country econometric models, has traditionally found gains to be modest.Footnote 39 This could be related to the fact that in these models international goods market spillovers tend to be very small, because a large part of the adjustment to shocks consists of relative price changes – which themselves tend to be relatively limited, especially with sticky prices and a low degree of trade integration.Footnote 40 Indeed, some studies based on alternative assumptions about real linkages between countries, based on calibrated, two-country simulation models did find potentially large gains from international monetary policy coordination (see, for instance, Liu and Pappa (2008)).

However, the most important reason as to why the early literature found only small gains from international monetary policy coordination may well be the fact that for the most part it did not account for various types of capital flows (bank and nonbank related) and largely abstracted from the financial system and its role in magnifying the response to shocks. Capturing the implications of greater international financial integration (including an increased role of global banks, as documented earlier) for capital flows, as well as financial frictions at home and abroad, could potentially make the welfare benefits from monetary policy coordination in response to the cross-border transmission of real and financial shocks significantly larger than the estimates provided by existing contributions.Footnote 41

In the area of macroprudential policy coordination, where contributions have only recently begun to emerge, these features have figured prominently in model design. In addition, some models also account for the fact that macroprudential regimes affect the monetary transmission mechanism – in line with the closed-economy literature on monetary policy.Footnote 42 As noted earlier, the international interconnectedness of financial markets, the possibility that regulatory leakages may weaken the ability of national policies to mitigate financial risks in a world with global financial institutions, and the fact that frictions in national financial systems can amplify the cross-border effects of domestic shocks, suggest indeed that significant gains from coordination may exist.Footnote 43

Nevertheless, model-based contributions focusing on the gains from international macroprudential policy coordination remain scarce. Instead, recent studies have focused more on measuring the magnitude of cross-border financial spillovers themselves, rather than providing quantitative estimates of the gains from coordination.Footnote 44 Among the few contributions available, based explicitly on a game-theoretic approach, are Chen and Phelan (2017), Agénor et al. (2018), and Agénor and Pereira da Silva (2019a).Footnote 45 The first study focuses on the case where financial frictions relate to the inability of countries to issue equity to each other. In that setting, coordinated macroprudential policies (in the form of borrowing limits) improves welfare. More related to our purpose in this paper, the second and third contributions study the gains from international macroprudential policy coordination in a two-region, core-periphery model with a global bank and financial frictions, with periphery banks borrowing from the core global bank to fund domestic lending. Both studies found that these gains, when unconstrained policies are used, are significant. In addition, gains are not equally distributed across countries; depending on the nature of the shock, gains for the periphery can be larger than those accruing to the core region. This could point to potential political-economy obstacles to the implementation of cooperative policies – an issue we return to later on.

4.3.3 Challenges in measuring the gains from coordination

The few studies summarized earlier provide several insights into what may affect, quantitatively, the gains from international macroprudential policy coordination. In particular, they suggest that the welfare gains from coordination are stronger when a) models are capable of generating large cross-border financial spillovers (as observed in recent years); b) financial frictions and financial amplification mechanisms at the level of individual countries are accounted for, as well as asymmetries in financial market imperfections across countries; and c) global regulators, entrusted to implement a cooperative solution, are able to internalize the fact that national regulators (despite being subject to collective action problems) may have a higher preference for financial stability. As a result, they may end up putting a higher weight on that objective in the global policy loss or welfare function. In fact, based on the previous discussion of the early literature on policy coordination, a better account of financial linkages between countries (especially through global financial institutions), assuming that they are associated with externalities that are not efficiently priced through movements in interest rates and real exchange rates, may be essential to generate large cross-border spillovers.