Summary

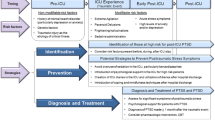

Critically ill patients, their relatives, and intensive care staff are consistently exposed to stress. The principal elements of this exceptional burden are confrontation with a life-threatening disease, specific environmental conditions at the intensive care unit, and the social characteristics of intensive care medicine. The short- and long-term consequences of these stressors include a feeling of helplessness, distress, anxiety, depression, and even posttraumatic stress disorders. Not only the patients, but also their relatives and intensive care staff are at risk of developing such psychopathologies. The integration of psychosomatic medicine into the general concept of intensive care medicine is an essential step for the early identification of fear and anxiety and for understanding biopsychosocial coherence in critically ill patients. Preventive measures such as the improvement of individual coping strategies and enhancing the individual’s resistance to stress are crucial aspects of improving wellbeing, as well as the overall outcome of disease. Additional stress-reducing measures reported in the published literature, such as hearing music, the use of earplugs and eye-masks, or basal stimulation, have been successful to a greater or lesser extent.

Zusammenfassung

Kritisch kranke Patienten sowie deren Angehörige und das betreuende medizinische Personal sind andauernden Stresssituationen ausgesetzt, die hauptsächlich mit der schweren Erkrankung selbst, der speziellen Umgebung der Intensivstation sowie den sozialen Interaktionen, welche die Intensivmedizin mit sich bringt, in Zusammenhang stehen. Gefühle von Hilflosigkeit, Verzweiflung, Angst, Depression und sogar posttraumatische Stressreaktionen können dabei als kurz- oder langfristige Folgen auftreten. Die Integration psychosomatischer Medizin ist bei Intensivpatienten ein wichtiger Schritt für das Erkennen von biopsychosozialen Zusammenhängen und deren Auswirkungen auf das Entstehen, den Verlauf und den Ausgang der Erkrankung. Präventive Maßnahmen, wie die frühzeitige Diagnose von Ängsten und Depressionen, die Förderung von Bewältigungsstrategien und die Stärkung der Resilienz können die Entwicklung von Psychopathologien bei gefährdeten Gruppen minimieren. Andere stressreduzierende Strategien, wie der Einsatz von basaler Stimulation, die Anwendung von Musik oder die Nutzung von Ohrstöpseln und Augenmasken haben sich als mehr oder weniger effizient herausgestellt.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Boer KR, van Ruler O, van Emmerik AA, et al. Factors associated with posttraumatic stress symptoms in a prospective cohort of patients after abdominal sepsis: a nomogram. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(4):664–74.

Fava GA, Cosci F, Sonino N. Current psychosomatic practice. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;86(1):13–30.

McGiffin JN, Galatzer-Levy IR, Bonanno GA. Is the intensive care unit traumatic? What we know and don’t know about the intensive care unit and posttraumatic stress responses. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61(2):120–31.

Cuesta JM, Singer M. The stress response and critical illness: a review. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(12):3283–9.

Lusk B, Lash AA. The stress response, psychoneuroimmunology, and stress among ICU patients. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2005;24(1):25–31.

Sukantarat K, Greer S, Brett S, et al. Physical and psychological sequelae of critical illness. Br J Health Psychol. 2007;12(Pt 1):65–74.

Carr J. Psychological consequences associated with intensive care treatment. Trauma. 2007;9:95–102.

Parker PA, Kulik JA. Burnout, self- and supervisor-rated job performance, and absenteeism among nurses. J Behav Med. 1995;18(6):581–99.

Wintermann GB, Brunkhorst FM, Petrowski K, et al. Stress disorders following prolonged critical illness in survivors of severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(6):1213–22.

Adler R, Herzog W, Joraschky P. et al. Psychosomatische Medizin, theoretische Modelle und klinische Praxis, 7th ed. München: Urban & Fischer; 2012.

Ganz FD. Tend and befriend in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurse. 2012;32(3):25–33.

Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):502–9.

Pochard F, Darmon M, Fassier T, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients before discharge or death. A prospective multicenter study. J Crit Care. 2005;20(1):90–6.

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422.

Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, et al. High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(7):686–92.

Embriaco N, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Burnout syndrome among critical care healthcare workers. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13(5):482–8.

Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, et al. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(7):698–704.

Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, et al. Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1871–6.

Malaquin S, Mahjoub Y, Musi A, et al. Burnout syndrome in critical care team members: A monocentric cross sectional survey. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2016; doi:10.1016/j.accpm.2016.06.011.

Jensen JF, Egerod I, Bestle MH, et al. A recovery program to improve quality of life, sense of coherence and psychological health in ICU survivors: a multicenter randomized controlled trial, the RAPIT study. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(11):1733–43.

Maley JH, Brewster I, Mayoral I, et al. Resilience in survivors of critical illness in the context of the survivors’ experience and recovery. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1351–60.

Pincock S. Bjørn Aage Ibsen. Lancet. 2007;370(9598):9598.

Master AM. Disturbances of rate and rhytm in acute coronary artery thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1937;11:735.

Lasch HG. Chances and limitations of intensive medicine. Med Welt. 1978;29(13):515–21.

Fenner E. Psychosomatische Forschung in Intensivstationen. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2001;51:T27–T45.

Gruen W. Effects of brief psychotherapy during the hospitalization period on the recovery process in heart attacks. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1975;43(2):223–32.

Foerster K. Supportive psychotherapy combined with autogenous training in acute leukemic patients under isolation therapy. Psychother Psychosom. 1984;41(2):100–5.

Cassem NH, Hackett TP. Psychiatric consultation in a coronary care unit. Ann Intern Med. 1971;75(1):9–14.

Kinzl J, Biebl W. Psychosomatischer Konsultationsdienst an der Universitätsklinik Innsbruck: Ein Kooperations- und Integrationsversuch. Prax Psychother Psychosom. 1992; 37:266–71.

Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1121–9.

Jackson JC, Hart RP, Gordon SM, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic stress symptoms following critical illness in medical intensive care unit patients: assessing the magnitude of the problem. Crit Care. 2007;11(1):R27.

Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(5):421–34.

Hu RF, Jiang XY, Hegadoren KM, et al. Effects of earplugs and eye masks combined with relaxing music on sleep, melatonin and cortisol levels in ICU patients: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2015;19:115.

Donchin Y, Seagull FJ. The hostile environment of the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2002;8(4):316–20.

Nikayin S, Rabiee A, Hashem MD, et al. Anxiety symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;43:23–9.

Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, et al. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(9):1744–53.

Zachariae R. Psychoneuroimmunology: a bio-psycho-social approach to health and disease. Scand J Psychol. 2009;50(6):645–51.

Le Blanc PM, de Jonge J, de Rijk AE, et al. Well-being of intensive care nurses (WEBIC): a job analytic approach. J Adv Nurs. 2001;36(3):460–70.

Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

Mealer ML, Shelton A, Berg B, et al. Increased prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in critical care nurses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(7):693–7.

Parshuram CS, Dhanani S, Kirsh JA, et al. Fellowship training, workload, fatigue and physical stress: a prospective observational study. Can Med Assoc J. 2004;170(6):965–70.

Fischer JE, Calame A, Dettling AC, et al. Experience and endocrine stress responses in neonatal and pediatric critical care nurses and physicians. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(9):3281–8.

Caplan RP. Stress, anxiety, and depression in hospital consultants, general practitioners, and senior health service managers. BMJ. 1994;309(6964):1261–3.

Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, et al. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):358–67.

Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, et al. Mental health of hospital consultants: the effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet. 1996;347(9003):724–8.

Ackerman AD. Retention of critical care staff. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(9 Suppl):S394–S5.

Weisman CS, Teitelbaum MA. Physician gender and the physician-patient relationship: recent evidence and relevant questions. Social science. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;20(11):1119–27.

McCue JD. The effects of stress on physicians and their medical practice. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(8):458–63.

Vahey DC, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, et al. Nurse burnout and patient satisfaction. Med Care. 2004;42(2 Suppl):II57–66.

Halbesleben JR, Rathert C. Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes: exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manage Rev. 2008;33(1):29–39.

Welp A, Meier LL, Manser T. Emotional exhaustion and workload predict clinician-rated and objective patient safety. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1573.

Borowitz SM, Waggoner-Fountain LA, Bass EJ, et al. Adequacy of information transferred at resident sign-out (in-hospital handover of care): a prospective survey. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(1):6–10.

Segall N, Bonifacio AS, Schroeder RA, et al. Can we make postoperative patient handovers safer? A systematic review of the literature. Anesth Analg. 2012;115(1):102–15.

Asch DA, Parker RM. The Libby Zion case. One step forward or two steps backward? N Engl J Med. 1988;318(12):771–5.

Fletcher KE, Parekh V, Halasyamani L, et al. Work hour rules and contributors to patient care mistakes: a focus group study with internal medicine residents. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(3):228–37.

Parshuram CS, Amaral AC, Ferguson ND, et al. Patient safety, resident well-being and continuity of care with different resident duty schedules in the intensive care unit: a randomized trial. Can Med Assoc J. 2015;187(5):321–9.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–94.

Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):618–24.

Lefkowitz DS, Baxt C, Evans JR. Prevalence and correlates of posttraumatic stress and postpartum depression in parents of infants in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17(3):230–7.

Shears D, Nadel S, Gledhill J, et al. Short-term psychiatric adjustment of children and their parents following meningococcal disease. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(1):39–43.

Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Gries CJ, et al. ICU care associated with symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder among family members of patients who die in the ICU. Chest. 2011;139(4):795–801.

Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, Kross EK, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression in family members after patient death in the ICU. Chest. 2010;137(2):280–7.

Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, et al. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(6):1722–8.

Rosendahl J, Brunkhorst FM, Jaenichen D, et al. Physical and mental health in patients and spouses after intensive care of severe sepsis: a dyadic perspective on long-term sequelae testing the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):69–75.

Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D, Schwartz TA, et al. Depressive symptoms in mothers of prematurely born infants. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(1):36–44.

Balluffi A, Kassam-Adams N, Kazak A, et al. Traumatic stress in parents of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5(6):547–53.

Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder-related symptoms in relatives of patients following intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):456–60.

Fröhlich A. Basale Stimulation: das Konzept. Düsseldorf: Selbstbestimmtes Leben; 2003.

Munninghoff B. Is basal stimulation with simultaneous noninvasive ventilation possible? Kinderkrankenschwester. 2008;27(8):333–8.

Ramsay P, Huby G, Merriweather J, et al. Patient and carer experience of hospital-based rehabilitation from intensive care to hospital discharge: mixed methods process evaluation of the RECOVER randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e012041.

Loomba R, Arora G, Shah P, et al. Effects of music on systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate: a meta-analysis. Indian Heart J. 2012;64(3):309–13.

Lee CH, Lee CY, Hsu MY, et al. Effects of music intervention on state anxiety and physiological indices in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit: a randomized controlled trial. Biol Res Nurs. 2017;19(2):137–44.

McGrath A, Reid N, Boore J. Occupational stress in nursing. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40(5):555–65.

Kentish-Barnes N, Lemiale V, Chaize M, et al. Assessing burden in families of critical care patients. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10 Suppl):S448–S56.

Hickey M. What are the needs of families of critically ill patients? A review of the literature since 1976. Heart Lung. 1990;19(4):401–15.

Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):469–78.

McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1484–8.

Mularski R, Curtis JR, Osborne M, et al. Agreement among family members in their assessment of the quality of dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(4):306–15.

Davidson JE, Daly BJ, Agan D, et al. Facilitated sensemaking: a feasibility study for the provision of a family support program in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2010;33(2):177–89.

Davidson JE. Facilitated sensemaking: a strategy and new middle-range theory to support families of intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Nurse. 2010;30(6):28–39.

Foa EB. Psychosocial therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 2):40–5.

Engstrom A, Andersson S, Soderberg S. Re-visiting the ICU Experiences of follow-up visits to an ICU after discharge: a qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2008;24(4):233–41.

Soderstrom IM, Saveman BI, Hagberg MS, et al. Family adaptation in relation to a family member’s stay in ICU. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2009;25(5):250–7.

Peskett M, Gibb P. Developing and setting up a patient and relatives intensive care support group. Nurs Crit Care. 2009;14(1):4–10.

Crocker C. A multidisciplinary follow-up clinic after patients’ discharge from ITU. Br J Nurs. 2003;12(15):910–4.

Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD, et al. Rehabilitation after critical illness: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(10):2456–61.

Wise TN. Psychosomatics: past, present and future. Psychother Psychosom. 2014;83(2):65–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

H. Abrahamian and D. Lebherz-Eichinger declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abrahamian, H., Lebherz-Eichinger, D. The role of psychosomatic medicine in intensive care units. Wien Med Wochenschr 168, 67–75 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-017-0575-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-017-0575-1