Abstract

Among African great apes, play is virtually absent between adult lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). Here, we report an extremely rare case of adult–adult play observed in the lowland gorilla group housed at La Vallée de Singes (France). We recorded three playful interactions between the silverback and an adult lactating female. Given the diverse causal and functional nature of play, different factors may join in promoting this behaviour. In our group, contrary to what has been shown by previous studies in wild and captive gorillas, adult females spent more time in spatial proximity with the silverback than with other females. Hence, the probability of social interaction (including play) between silverback and adult females was enhanced. Moreover, the motivation of the lactating female to play might be an effect of oxytocin, a hormone that reaches high concentration levels during lactation and that promotes social affiliation. The fact that play invitations were always performed by the female might support this hypothesis. Certainly, we cannot exclude the possibility that the play event is a group idiosyncrasy or an artefact of captivity, even though the subjects never showed abnormal behaviour. Structurally, play sessions showed a suitable degree of pattern variability and switching frequency from one pattern to another. The proportion of offensive patterns was higher in the female during play and in the male during aggression, which conforms to the role reversal play phenomenon. In conclusion, this report confirms that the absence of evidence is not the evidence of absence. It is likely that under particular physiological or socio-ecological conditions, adult–adult play may be manifested as an “unconventional” part of gorilla social behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In human and non-human primates, social play is widespread among immature individuals and is considered the main social interaction characterizing the juvenile developmental phase (Fairbanks 2000; Cordoni and Palagi 2011). Conversely, adult–adult play has been described in only about 50% of primate species (Pellis and Iwaniuk 1999, 2000). Following a phylogenetic logistic regression analysis, O’Meara and colleagues (2015) could not single out any correlations between the maintenance of play in adulthood and metabolic (e.g. basal metabolic rate), socio-ecological (e.g. group size) or life-history (e.g. age at sexual maturity) variables. This finding supports the diverse causal and functional nature of adult social play behaviour in primates.

African great apes show frequent and quite stable levels of social play in the immature phase (Fagen 1981; Palagi et al. 2007; Cordoni and Palagi 2011; Palagi and Cordoni 2012; Cordoni et al. 2018), but the level of play during adulthood varies greatly depending on the species. In bonobos (Pan paniscus), adult–adult play remains relatively frequent across different sex/age-class combinations and contexts (Palagi et al. 2006; Palagi and Paoli 2007; Palagi and Cordoni 2012). In chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), adult–adult playful interactions are less frequent compared to bonobos, although they can still be observed as a means for reducing social tension and strengthening affiliative bonds (Palagi et al. 2004; Cordoni and Palagi 2011; Yamanashi et al. 2018). Although infrequent, social play in adult mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) has mainly been reported between mature males living in multi-male or bachelor groups (Yamagiwa 1992; Watts and Pusey 1993; Grueter et al. 2016). In lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla), social play plummets when approaching sexual maturity and is virtually absent between adults (Stewart and Harcourt 1987; Palagi et al. 2007, 2019; Masi et al. 2009; Cordoni et al. 2018).

Here, we report and describe a rare case of adult–adult play in captive lowland gorillas that was observed between the silverback and an adult female. In the wild, lowland gorillas mainly constitute one-male units comprising an adult male (the silverback), several adult females and their offspring (Fleagle 2013). Mature males can temporarily associate in the so-called bachelor groups during the period of dispersion from their natal groups (Robbins and Robbins 2018; Forcina et al. 2019; Hagemann et al. 2019). Before their first reproductive event, females also disperse from their original groups, and they preferentially join smaller groups led by younger and stronger silverbacks (Stokes 2004; Manguette et al. 2020). Even if affinitive interactions may be present at variable levels in lowland gorillas (Forcina et al. 2019; Cooksey et al. 2020), social contacts (e.g. allo-grooming) between adults are less frequent compared to other great apes (Stokes 2004; Cordoni and Palagi 2007; Masi et al. 2009; Cordoni et al. 2018). In the wild, Stokes (2004) reported only eight affiliative events (i.e. sexual interactions and contact sitting) between adults during 802 hours of observation; intriguingly, six out of eight contacts occurred between the silverback and the reproductive females. In both captive and wild gorillas, first post-conflict affinitive contacts between former opponents (reconciliation sensu de Waal and Roosmalen 1979) occurred more frequently between the alpha male and adult females compared to other dyads, possibly aimed at restoring a peaceful relationship between these subjects (Watts 1995, 2000; Cords and Aureli 2000; Cordoni et al. 2006). Different results have been obtained for spatial proximity (Watts 1994; Stokes 2004; Lemasson et al. 2018). Indeed, in captive lowland gorillas, it has been observed that adult females (particularly females with newborns) did not maintain close proximity with the silverback, and they even preferred staying in spatial closeness with other group members (Fischer 1983; Nakamichi and Kato 2001; Stoinski et al. 2003). As concerns play, in two captive groups housed at the ZooParc de Beauval (France), Cordoni and co-authors (2018) reported extremely low frequencies of playful interactions between adults and immature subjects (mean individual hourly frequency = 0.023 ± 0.015SE), and social play was never observed between adults. In the wild (Odzala-Kokoua National Park; Congo), Forcina and colleagues (2019) qualitatively reported playful interactions between adult females of different groups, but never between adult females and the silverback.

Given the extremely rare occurrence of adult–adult play in lowland gorillas, very little is known about how adults engage in and manage playful interactions. In this report, we structurally describe the social play observed between the silverback and a lactating female, as a starting point for future research on modality, complexity and possible function/s of play in adult gorillas. Due to the complex nature of play, different factors, not mutually exclusive, may join in promoting adult–adult play, such as inter-individual closeness (e.g. spatial proximity), physiological conditions (e.g. lactating period) and individual characteristics (e.g. play propensity). We discuss different scenarios in the possible hypotheses explaining the occurrence of this playful event.

Study site and subjects

The study was carried out on the family group of lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) housed at La Vallée des Singes (Romagne, France). The group comprised 10 individuals (see Table 1). The silverback sired all immature subjects. Only one adult female (Virunga) in the group had no offspring. During the observations, the primiparous female Mahmah was lactating. The gorilla enclosure included both an indoor and an outdoor facility of about 150 and 3400 m2, respectively. The outdoor space was a natural wooded island surrounded by a water canal, and the indoor enclosure was enriched with lianas, trunks, straw and platforms. Gorillas were fed outdoors with fruit and vegetables five times per day during spring and summer (May–Aug: 11:15, 14:00, 15:30, 17:00 and 18:00) and twice per day starting from September (Sep–Apr: 11:15 and 15:30). Water was provided ad libitum. Gorillas were free to move between the indoor and outdoor enclosures and to socially interact. No aberrant or stereotypic behaviour was observed.

Data collection and operational definitions

We collected video data during August–October 2020 and March–June 2021 on a daily basis spanning morning and afternoon and including all feeding times. The videos were recorded by one author (SE) using a Panasonic HDC-SD9 video camera. In total, about 72.5 hours of videos were collected. The videos were analysed—also through a frame-by-frame analysis when necessary—via the freeware Avidemux 2.7.8. Before starting the video analysis, GC supervised LP in a training period of 15 hours to reach suitable agreement in individual gorilla recognition and in the classification of behavioural patterns and facial expressions. The interobserver reliability reached Cohen's κ value of 0.78 for individual recognition and 0.74 for behaviour classification (considered behaviours: play, playful facial expressions, aggression, affiliation).

Following Altmann (1974), we employed scan sampling for evaluating baseline activities and spatial distance between subjects (i.e. resting, moving, feeding, spatial proximity, body contact, grooming, play, aggression). Spatial proximity was defined as an arm-length distance between two gorillas. We carried out group scans at 10-minute intervals by collecting a total of 132 scans (22 hours of observation). We also employed all occurrences sampling for recording playful/aggressive events (50.5 hours of observation).

For each playful/aggressive event we reported (i) the identities of the interacting subjects (age and sex) and which of them initiated the session, (ii) behavioural patterns performed in their chronological order (see Table 2 for definition of behavioural patterns), and only for play, (iii) facial expressions (play face, PF; full play face, FPF; see Table 2) and their duration (centiseconds) and (iv) session duration (seconds).

We considered that a play session started when an individual performed any playful pattern (see Table 2) towards a companion and finished when both subjects stopped the interaction (Cordoni et al. 2021). As suggested in the play literature, two consecutive sessions were considered as different sessions if the play interaction stopped for more than 10 seconds (Mancini et al., 2013; Davila-Ross et al., 2015; Cordoni et al. 2016, 2018). In our case, between the first (duration = 35 seconds) and the second (duration = 30 seconds) play session there was a time gap of 35 seconds and between the second and the third session (duration = 270 seconds) the time gap was 20 seconds. Hence, we treated the sequences as three separate playful events. During the play-pause, the silverback and the adult female maintained their spatial proximity and performed self-grooming.

We considered that an aggressive session started when a gorilla directed any aggressive pattern (see Table 2) towards a group mate and usually ended with one of the opponents moving or fleeing.

We classified playful patterns into three categories (see Table 2): (1) offensive (i.e. attack/pursuit playful patterns giving one of the playmates a clear physical advantage over the partner); (2) defensive (i.e. playful patterns by which the player tries to shelter from the playful attack by the partner); (3) neutral (locomotor/acrobatic patterns, possibly involving an object).

To evaluate the asymmetry of each interaction, for each involved party we defined a play asymmetry index (PAI) as “the proportion of offensive patterns performed by A towards B plus the defensive patterns performed by B towards A” subtracted from “the proportion of offensive patterns performed by B towards A plus the defensive patterns performed by A towards B” divided by “the total number of patterns performed by both playmates” (Cordoni et al. 2016, 2018). The PAI ranges from −1 to +1, with main values indicating (i) complete symmetry of the session (zero), (ii) complete asymmetry of the session in favour of A (+1) and (iii) complete asymmetry of the session in favour of B (−1).

For comparative purposes, outside of the play context we also calculated an aggression asymmetry index (AAI). We considered as (i) “offensive” all patterns performed to threaten/attack/pursue an opponent, (ii) “defensive” all patterns performed to avoid/shelter from an opponent's attack and (iii) “neutral” all patterns not classified as offensive or defensive (see Table 2). AAI was defined as follows: “the proportion of offensive patterns performed by A towards B plus the defensive patterns performed by B towards A” subtracted from “the proportion of offensive patterns performed by B towards A plus the defensive patterns performed by A towards B” divided by “the total number of patterns performed by both opponents”. Like the PAI, the AAI ranges from −1 to +1, with main values indicating (i) complete symmetry of the session (zero), (ii) complete asymmetry of the session in favour of A (+1) and (iii) complete asymmetry of the session in favour of B (−1).

We carried out a sequential analysis to evaluate the temporal association between different behavioural patterns. We created a string for each play session by reporting the patterns separated by a break symbol (i.e. |). The resulting string represented the ordered concatenation of patterns as they occurred during each playful interaction. Then, we employed the free open-source software Behatrix 0.9.11 (http://www.boris.unito.it/pages/behatrix; Friard and Gamba, 2020) to analyse the sets of behavioural sequences and organize data into contingency tables. The program generates the code for a flow diagram (Graphviz script) of behaviour-to-behaviour transitions. Via Behatrix, we also calculated the Levenshtein distance, a string metric for measuring the difference between two sequences (Levenshtein 1966; Kruskal, 1999).

Results

General and contextual data

In the gorilla colony under study, we collected a total of 590 play sessions, 83 of which involved at least one adult subject. In particular, we recorded three sessions between the silverback (Yaoundé) and the lactating female (Mahmah) and 80 sessions between an adult and an immature subject (number of sessions: 62 Mahmah, 13 Hakuna and 5 Yaoundé). Moreover, we collected 226 aggressive interactions, three of which involved adults. The three aggressions were directed by the silverback towards two adult females (Virunga and Hakuna). No aggression was recorded between the silverback and the lactating female (Mahmah). The spatial proximity between the silverback and adult females accounted for 26% of the proximity bouts (mean dyadic value 1.6 ± 2.1 SD), whereas adult female dyads only accounted for 9.3% of the proximity bouts (mean dyadic value 0.8 ± 3.5 SD).

Adult playful interactions

On 27 September 2020, we video-recorded three playful sessions between the silverback (Yaoundé) and a lactating female (Mahmah). It was a rainy day and the gorillas spent the whole day indoors, although they had free access to the outdoor enclosure. The group did not receive any energy-rich or special food. No changes were made in the usual routine management. No particular social or environmental stressful event or aggression among group-members occurred during the day. Play sessions occurred during resting time (session #1 occurred at 16:11; session #2 at 16:12; session #3 at 16:15; see video clip in Supporting material), and the two players were in strict proximity or body contact with the immature individuals of the group, including Mahmah’s 3-month old son (Basoko; see Table 1). We did not observe any playful interactions among immature subjects immediately before the Mahmah–Yaoundé play sessions. In all cases, the adult female invited the silverback to play by directing playful contact patterns towards him (i.e. play bite and play pat; see Table 2). It is worth noting that throughout the three adult–adult play sessions, the immature individuals (excluding the newborn, Basoko) tried unsuccessfully to interrupt or join the interaction.

Play behavioural sequence

We recorded 13 different types of patterns constituting the three play sessions. A total of 37 transitions occurred between behavioural patterns (see Table 3). The Levenshtein distance values ranged from 6 to 20, thus indicating a difference in the composition of the three sessions, particularly between sessions #1 and #2 and #2 and #3 (Table 3).

Play and symmetry

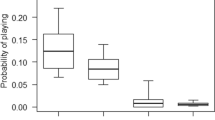

As concerns the symmetry of the session, the medians of PAI (−0.83) and AAI (1.00) indicated two opposite directions (Fig. 1). While in the aggressive context the interaction was completely asymmetric in favour of the silverback, during play the roles of playmates were reversed, with the adult female “dominating” the interaction with the silverback.

Histogram representing the median values of the AAI and PAI based on aggressive encounters and playful interactions involving the silverback and/or the lactating adult female. The value +1.0 of AAI indicates that during aggression, the silverback performed a higher proportion of offensive and less of defensive patterns compared to the adult female. Conversely, the value around −1.0 of PAI indicates that during play, the adult female performed a higher proportion of offensive and less of defensive patterns compared to the silverback. See the text for definitions of offensive and defensive aggressive/playful patterns

Playful facial expressions

Among the recorded playful patterns, 17.5% were facial expressions mainly performed by the silverback (two play faces, PF, and four full play faces, FPF). The sequential analysis (Fig. 2) showed that PF and FPF performed by both the silverback and the adult female were immediately followed or preceded by a typical playful offensive pattern, that is, play bite (transition occurrence % FPF ↔ play bite = 76.7%; transition occurrence % PF ↔ play bite = 73.4%). In one of the three sessions, namely session #2, the silverback directed a play bite towards the female, and immediately after he performed a FPF while engaging in a face-to-face interaction with Mahmah. Mahmah responded to Yaoundé with a PF and concomitantly directed a play bite towards him (see supporting video material).

Flow diagram representing behaviour-to-behaviour transitions in the three playful sessions recorded between the silverback and lactating adult female. Legend (see Table 2 for pattern definitions): abit attempt play bite, fpf full play face, pat play pat, pbit play bite, pf play face, pinv play invitation, plgr play grab, pps play push, ppu play pull, pre play retrieve, psh play push, psl play slap

Play and affiliation

During session #2, between two play-biting events the silverback groomed the female for less than 10 seconds (grooming was not part of play; transition occurrence % play bite → grooming 6.67% and grooming → play bite 100%). Generally, during grooming, a gorilla manipulates the fur, extremity or orifice of a companion; grooming may include both manual and oral components (Cordoni & Palagi, 2007). No other grooming bout involving the adults was recorded throughout the duration of our study.

Discussion

Presence of adult–adult play

In the current captive study on lowland gorillas, we structurally described three social play interactions between a silverback and an adult female. The novelty of our investigation relies on the report that adult–adult play—although extremely rare—is part of the behaviour of lowland gorillas and can be shown at least under certain circumstances. To our knowledge, no report on play modalities between the silverback and adult females is available in the literature for the study species. Considering that the two subjects involved in the play sessions were born and mother-reared in captivity and thus had no particular history of exploitation in the entertainment industry, we can reasonably exclude that the observed patterns have to be considered as abnormal behaviours. It is possible that the occurrence of such behaviour can be facilitated by the safe social and ecological environment in which the gorillas lived.

In this study, contrary to what is reported in the literature on wild and captive lowland gorillas (Fischer 1983; Stoinski et al. 2003; Stokes 2004; Nakamichi et al. 2014; Klailova and Lee 2014), adult females spent more time in spatial proximity to the silverback than to other females. In this view, the probability of social interaction (including play) between the silverback and adult females was enhanced. However, we observed social play between the silverback and one specific adult female, but not between the silverback and any female. Play specifically involved the only lactating female.

Greater concentrations of oxytocin—a neuropeptide hormone—are associated with lactation and milk ejection (Carter et al. 2007; White-Traut et al. 2009). Moreover, even though the relation between oxytocin and social behaviour is highly complex, this hormone could have an effect in creating mother–infant bond, increasing affinitive interactions, forming inter-individual relationships and, in some cases, promoting play (Wallen and Hassett 2009; Insel 2010; Carter 2014; Vanderschuren and Trezza 2014; Numan and Young 2016; Vanderschuren et al. 2016). Hence, in our study the motivation of the female to play might have been increased during lactation. This hypothesis is also supported by the fact that play invitations were always performed by the lactating female towards the silverback. Of course, a much larger sample is necessary to verify this hypothesis. In addition, general levels of play performed by adult females with both other adults and immature subjects should be evaluated before and after the lactation period and compared with levels during lactation. Higher general levels of play during lactation than during non-lactating periods would further support our hypothesis.

Play is considered a by-product of the interaction and rearrangement of different behavioural systems (e.g. aggressive and sexual domains), and its motor patterns resemble those used in these “serious” contexts (Pellis et al. 2019). One of the major risks of play is the misinterpretation of the pattern performed/received by playmates and the consequent escalation of the session into aggression (Pellis and Pellis 1996; Palagi et al. 2016a). In the wild, both mountain and lowland lactating female gorillas receive less aggression by the silverback compared to cycling and pregnant females (Robbins 2009; Breuer et al. 2016). Hence, in our case the risk of the lactating female of receiving an aggressive response by the silverback could be lowered, thus facilitating the start and maintenance of the playful interaction.

In wild mountain gorillas, Grueter and colleagues (2016) recorded two playful interactions between the silverback and adult females in one out of the three groups under observation. The authors did not exclude the possibility that social play could be an effect of food intoxication. In this respect, social play was considered an abnormal, toxin-induced behaviour. Intoxication due to plant consumption was never observed in the study group, and no toxic plants seem to be present in the outdoor enclosure. Therefore, it seems unlikely that social play in our study group was triggered by toxins.

It is also worth noting that during the day in which adult–adult play was observed, gorillas remained mainly inside, and they probably had been expending less energy compared to other ordinary days. The surplus energy theory of play (Barber 1991) proposed that animals can consume the energy in “excess of need” by playing. In this view, adult–adult play could be favoured by an excess of energy subjects have to expend. Nevertheless, in our case the gorilla keepers who have been working with this group for over 20 years told us that they had never observed Yaoundé playing with adult females during “less energy-expending days”.

We can hypothesize that under particular physiological and/or socio-ecological conditions—in our case the possible effects of oxytocin and more frequent spatial proximity—adult–adult play may be present as a rare and “unconventional” part of gorilla social behaviour. Certainly, we cannot exclude the possibility that what we observed is linked to idiosyncratic factors deriving from particular individual life history events that we ignore (e.g. behavioural acquisition caused by prolonged interactions with humans) or to more extroverted personality traits (Racevska and Hill 2017) favouring the play propensity of the lactating female. Moreover, we cannot rule out the possibility that play behaviour in adult gorillas might be an artefact of captivity, although we believe that if this were the case, play behaviour should be much more commonly observed in the captive groups of this species.

Structure of the play sessions

From a structural point of view, the recorded play sessions showed a degree of variability in the motor patterns performed (13 different types of play patterns; see Table 3) and in the frequency of switching from one pattern to another (37 transitions for a total of 40 patterns performed; see Table 3). In 2011, Burghardt (2011) proposed five criteria for a behaviour to be considered play. In particular, play behaviour (i) does not appear completely functional, (ii) is spontaneous, voluntary and rewarding, (iii) includes patterns exaggerated and modified in their sequences, (iv) comprises repeated but not stereotyped patterns and (iv) is performed in a relatively relaxed context. Our observations are in line with the third and the fourth criteria, which are mainly centred on the behavioural structure of play in terms of pattern repetition and exaggeration.

In our case, we observed that play facial expressions (PF and FPF) mainly occurred immediately before or after an offensive playful pattern. From a classical ethological point of view, PF and FPF are ritualized displays that drive information to the receiver on possible future actions of the play companion. By doing so, such displays reduce the uncertainty concerning the nature of the interaction (Bekoff and Allen 1998; Pellis and Pellis, 1996; Bekoff 2001). Play faces also convey a positive emotional state of playmates (Palagi et al. 2016b, 2019, 2020; but see: Bliss-Moreau and Moadab 2017). It is likely that PF and FPF not only function in communicating the benign intent of the playmate (particularly the silverback), but also allow individuals to potentially share their playful mood.

Finally, the partner roles during play were reversed; indeed, the adult female directed more offensive patterns towards the silverback than vice versa. This strategy is often used by strong, old and dominant individuals for maintaining play with partners having fewer physical abilities and lower hierarchical status (self-handicapping and role reversal; Power 2000; Petru et al. 2009).

In conclusion, this case report confirms that “the absence of evidence does not indicate the evidence of absence”. Although extremely rare, it can be stated that social play between adults is present in lowland gorillas, although its expression may occur in particular individuals living in particular social groups and under particular (if not exceptional) circumstances.

References

Altmann J (1974) Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour 49:227–267. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853974X00534

Barber N (1991) Play and energy regulation in mammals. Q Rev Biol 66:129–147. https://doi.org/10.1086/417142

Bekoff M (2001) Social play behaviour: cooperation, fairness, trust, and the evolution of morality. J Consc Stud 8:81–90

Bekoff M, Allen C (1998) Intentional communication and social play: how and why animals negotiate and agree to play. In: Bekoff M, Byers JA (eds) Animal play: evolutionary, comparative, and ecological perspectives. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 97–114

Bliss-Moreau E, Moadab G (2017) The faces monkeys make. In: Fernández-Dols JM, Russel JA (eds) The science of facial expression. Oxford University Press, Oxford (UK), pp 153–171

Breuer T, Robbins AM, Robbins MM (2016) Sexual coercion and courtship by male western gorillas. Primates 57:29–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-015-0496-9

Burghardt GM (2011) Defining and recognizing play. In: Nathan P, Pellegrini AD (eds) The Oxford handbook of the development of play. Oxford University Press, Oxford (UK), pp 9–18

Carter CS (2014) Oxytocin pathways and the evolution of human behavior. Ann Rev Psychol 65:17–39. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115110

Carter CS, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Kramer KM et al (2007) Oxytocin: behavioral associations and potential as a salivary biomarker. Ann NY Acad Sci 1098(1):312–322. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1384.006

Cooksey K, Crickette S, Thierry FE et al (2020) Socioecological factors influencing intergroup encounters in western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). Int J Primatol 41:181–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-020-00147-6

Cordoni G, Palagi E (2007) Response of captive lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) to different housing conditions: testing the aggression-density and coping models. J Comp Psychol 121(2):171–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7036.121.2.171

Cordoni G, Palagi E (2011) Ontogenetic trajectories of chimpanzee social play: similarities with humans. PlosOne 6:e27344. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027344

Cordoni G, Palagi E, Tarli SB (2006) Reconciliation and consolation in captive western gorillas. Int J Primatol 27(5):1365–1382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-006-9078-4

Cordoni G, Nicotra V, Palagi E (2016) Unveiling the ‘secret’ of dog play success: asymmetry and signals. J Comp Psychol 130(3):278–287. https://doi.org/10.1037/com0000035

Cordoni G, Norscia I, Bobbio M, Palagi E (2018) Differences in play can illuminate differences in affiliation: a comparative study on chimpanzees and gorillas. PLoS One 13(3):e0193096. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193096

Cordoni G, Gioia M, Demuru E, Norscia I (2021) The dark side of play: play fighting as a substitute for real fighting in domestic pigs, Sus scrofa. Anim Behav 175:21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2021.02.016

Cords M, Aureli F (2000) Reconciliation and relationship qualities. In: Aureli F, de Waal FBM (eds) Natural conflict resolution. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp 177–198

Davila-Ross M, Jesus G, Osborne J, Bard KA (2015) Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) produce the same types of ‘laugh faces’ when they emit laughter and when they are silent. PLoS ONE 10(6):e0127337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127337

de Waal FBM, van Roosmalen A (1979) Reconciliation and consolation among chimpanzees. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 5:55–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00302695

Fagen R (1981) Animal play behavior. Oxford University Press, New York

Fairbanks LA (2000) The developmental timing of primate play. A neural selection model. In: Parker ST, Langer J, McKinney ML (eds) Biology, brains, and behaviour—the evolution of human development. School of American Research Press, Santa Fe, pp 211–219

Fischer RB (1983) Maternal subgrouping in lowland gorillas. Behav Process 8:301–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/0376-6357(83)90019-0

Fleagle JG (2013) Primate adaptation and evolution. Academic press, Cambridge

Forcina G, Vallet D, Le Gouar PJ et al (2019) From groups to communities in western lowland gorillas. Proc R Soc B 286:20182019. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.2019

Friard O, Gamba M (2020) Behatrix: behavioral sequences analysis with permutations test. Retrieved from http://www.boris.unito.it/pages/behatrix. Accessed August 31, 2021

Grueter CC, Robbins MM, Abavandimwe D et al (2016) Elevated activity in adult mountain gorillas is related to consumption of bamboo shoots. J Mammal 97(6):1663–1670. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyw132

Hagemann L, Arandjelovic M, Robbins MM et al (2019) Long-term inference of population size and habitat use in a socially dynamic population of wild western lowland gorillas. Conserv Genet 20:1303–1314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-019-01209-w

Insel TR (2010) The challenge of translation in social neuroscience: a review of oxytocin, vasopressin, and affiliative behavior. Neuron 65:768–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.005

Klailova M, Lee PC (2014) Wild western lowland gorillas signal selectively using odor. PLoS One 9(7):e99554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099554

Kruskal JB (1999) An overview of sequence comparison. In: Sankoff D, Kruskal J (eds) Time warps, string edits and macromolecules. The theory and practice of sequence comparison, 2nd edn. CSLI, Stanford, pp 1–44

Lemasson A, Pereira H, Levréro F (2018) Social basis of vocal interactions in western lowland gorillas (Gorilla g. gorilla). J Comp Psychol 132(2):141–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/com0000105

Levenshtein VI (1966) Binary codes capable of correcting deletions, insertions, and reversals. Cybernet Contr Theor 10(8):707–710

Mancini G, Ferrari P, Palagi E (2013) Rapid facial mimicry in geladas. Sci Rep 3:1527. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01527

Manguette ML, Robbins AM, Breuer T et al (2020) Female dispersal patterns influenced by male tenure duration and group size in western lowland gorillas. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 74(7):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-020-02863-8

Masi S, Cipolletta C, Robbins MM (2009) Western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) change their activity patterns in response to frugivory. Am J Primatol 71:91–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20629

Nakamichi M, Kato E (2001) Long-term proximity relationships in a captive social group of western lowland gorillas. Zoo Biol 20:197–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.1020

Nakamichi M, Onishi K, Silldorf A et al (2014) Twelve-year proximity relationships in a captive group of western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) at the San Diego Wild Animal Park, California, USA. Zoo Biool 33(3):173–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21131

Numan M, Young LJ (2016) Neural mechanisms of mother–infant bonding and pair bonding: similarities, differences, and broader implications. Horm Behav 77:98–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.05.015

O’Meara BC, Graham KL, Pellis SM et al (2015) Evolutionary models for the retention of adult–adult social play in primates: the roles of diet and other factors associated with resource acquisition. Adap Behav 23(6):381–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059712315611733

Palagi E, Cordoni G (2012) The right time to happen: play developmental divergence in the two Pan species. PLoS One 7:e52767. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052767

Palagi E, Paoli T (2007) Play in adult bonobos (Pan paniscus): modality and potential meaning. Am J Phys Anthropol 134:219–225. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.20657

Palagi E, Cordoni G, Borgognini Tarli SM (2004) Immediate and delayed benefits of play behaviour: new evidence from chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Ethology 110(12):949–962. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2004.01035.x

Palagi E, Paoli T, Tarli SB (2006) Short-term benefits of play behavior and conflict prevention in Pan paniscus. Int J Primatol 27(5):1257–1270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-006-9071-y

Palagi E, Antonacci D, Cordoni G (2007) Fine-tuning of social play in juvenile lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). Dev Psychobiol 49(4):433–445. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.20219 (PMID: 17455241)

Palagi E, Burghardt GM, Smuts B et al (2016a) Rough-and-tumble play as a window on animal communication. Biol Rev 91:311–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12172

Palagi E, Cordoni G, Demuru E et al (2016b) Fair play and its connection with social tolerance, reciprocity and the ethology of peace. Behaviour 153:1195–1216. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568539X-00003336

Palagi E, Norscia I, Cordoni G (2019) Lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) failed to respond to others’ yawn: experimental and naturalistic evidence. J Comp Psychol 133(3):406–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/com0000175

Palagi E, Celeghin A, Tamietto M et al (2020) The neuroethology of spontaneous mimicry and emotional contagion in human and non-human animals. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 111:149–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.01.020

Pellis SM, Iwaniuk AN (1999) The problem of adult play fighting: a comparative analysis of play and courtship in primates. Ethology 105:783–806. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0310.1999.00457.x

Pellis SM, Iwaniuk AN (2000) Adult-adult play in primates: comparative analyses of its origin, distribution and evolution. Ethology 106:1083–1104. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0310.2000.00627.x

Pellis SM, Pellis VC (1996) On knowing it’s only play: the role of play signals in play fighting. Aggr Viol Behav 1:249–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/1359-1789(95)00016-X

Pellis SM, Pellis VC, Pelletier A et al (2019) Is play a behavior system, and if so, what kind? Behav Process 160:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2018.12.011

Petru M, Špinka M, Charvátová V et al (2009) Revisiting play elements and self-handicapping in play: a comparative ethogram of five Old World monkey species. J Comp Psychol 123:250–263. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016217

Power TG (2000) Play and exploration in children and animals. ErlbaumL, Mahwah, New Jersey

Racevska E, Hill CM (2017) Personality and social dynamics of zoo-housed western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). JZAR 5(3):116–122. https://doi.org/10.19227/jzar.v5i3.275

Robbins MM (2009) Male aggression toward females in mountain gorillas: courtship or coercion? In: Muller MN, Wrangham RW (eds) Sexual coercion in primates and humans: an evolutionary perspective on male aggression against females. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, pp 112–127

Robbins MM, Robbins AM (2018) Variation in the social organization of gorillas: life history and socioecological perspectives. Evolut Anthropol 27(5):218–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21721

Stewart K, Harcourt AH (1987) Gorillas: variation in female relationships. In: Smuts BB, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM, Wrangham RW, Struhsaker TT (eds) Primate societies. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 155–164

Stoinski TS, Hoff MP, Maple TL (2003) Proximity patterns of female western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) during the six months after parturition. Am J Primatol 61(2):61–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.10110

Stokes EJ (2004) Within-group social relationships among females and adult males in wild western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). Am J Primatol 64(2):233–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20074

Vanderschuren LJ, Trezza V (2014) What the laboratory rat has taught us about social play behavior: role in behavioral development and neural mechanisms. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 16:189–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2013_268

Vanderschuren LJ, Achterberg EM, Trezza V (2016) The neurobiology of social play and its rewarding value in rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 70:86–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.025

Wallen K, Hassett J (2009) Neuroendocrine mechanisms underlying social relationships. In: Ellison PT, Gray PB (eds) Endocrinology of social relationships. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, pp 32–53

Watts DP (1994) Social relationships of immigrant and resident female mountain gorillas. II. Relatedness, residence, and relationships between females. Am J Primatol 32:13–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.1350320103

Watts DP (1995) Post-conflict social events in wild mountain gorillas (Mammalia, Hominoidea). I. Social Interactions between opponents. Ethology 100:139–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.1995.tb00321.x

Watts DP (2000) Causes and consequences of variation in male mountain gorilla life histories and group membership. In: Kappeler P (ed) Primate males. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (UK), pp 169–179

Watts DP, Pusey AE (1993) Behavior of juvenile and adolescent great apes. In: Pereira ME, Fairbanks LA (eds) Juvenile primates: life history, development, and behavior. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 148–167

White-Traut R, Watanabe K, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H et al (2009) Detection of salivary oxytocin levels in lactating women. Develop Psychobiol 51(4):367–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.20376

Yamagiwa J (1992) Functional analysis of social staring behavior in an all-male group of mountain gorillas. Primates 33(4):523–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02381153

Yamanashi Y, Nogami E, Teramoto M et al (2018) Adult-adult social play in captive chimpanzees: is it indicative of positive animal welfare? App Anim Behav Sci 199:75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2017.10.006.E

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank La Vallée des Singes (France) and, in particular, the gorilla keepers for allowing and facilitating this work and for all the information they provided concerning the group and the individuals.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: GC; methodology: GC and IN; training for data collection: ED; data collection: SE; video analysis and data coding: LP; formal analysis and investigation: GC and IN; writing—original draft preparation: GC and IN; writing—review and editing: GC and IN; access to the study setting and MS revision: J-PG.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

No informed consent was needed.

Research involving human or animal participants

The current research was purely observational, with no manipulation of animals.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Video of an indoor playful interaction between the silverback (Yaoundé) and lactating female (Mahmah) of the lowland gorilla colony housed at La Vallée des Singes (France) on 27 September 2020. In the video-clip the salient parts of the playful interaction are described. The two infants (Kouam and Ivindo) and one of the two sub-adult males (Mawete) are in proximity of the players throughout the interaction and unsuccessfully try to join play. Mahmah sits in contact with her newborn (Basoko) during the interaction. Video by Stéphanie Elies. Editing by Giada Cordoni (MP4 125505 KB)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Cordoni, G., Pirarba, L., Elies, S. et al. Adult–adult play in captive lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). Primates 63, 225–235 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-022-00973-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-022-00973-7