Abstract

In November 2017, the European Global Navigation Satellite System Agency (GSA) released geometrical and optical information for the Galileo satellites which allowed for the composition of a box-wing model whose main goal is absorption of the direct solar radiation pressure, earth’s albedo, and infrared radiation. In order to evaluate the efficiency of the box-wing model, we test solutions based solely on the empirical models, the pure analytical box-wing model, and a series of hybrid models including the box-wing with different sets of additionally estimated empirical parameters. The hybrid solution, which is based on the box-wing model and on a reduced number of estimated empirical parameters, substantially reduces variabilities of the satellite laser ranging (SLR) residuals, especially for the low elevation angles of the sun above the orbital plane (β), i.e., for eclipsing Galileo satellites. The standard deviation of SLR residuals for |β| < 12.3° decreases from 37 to 25 mm between the solution based on the ECOM2 and the hybrid solution, respectively. We found significant mitigation of the spurious geocenter signal in the Z component and its formal errors, when reducing the number of estimated empirical parameters, and a substantial reduction of the dependency between geocenter coordinates, the geometry of Galileo orbital planes, and the position of the sun. The hybrid box-wing solution with a reduced set of empirical parameters provides thus the best solution for precise orbit determination, orbit predictions, and estimation of geodetic parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The European navigation satellite system Galileo has been under development since the beginning of the twenty-first century (Montenbruck et al. 2006; Steigenberger et al. 2011). Today, the Galileo constellation consists of 26 spacecraft, i.e., four in-orbit validation (IOV) satellites, out of which satellite GAL-104 transmits signal at one frequency, and 22 fully operational capability (FOC) satellites, out of which two fly at highly elliptical orbits and one has been removed from the operational services due to the clock issues (Steigenberger and Montenbruck 2017). The full operational capability is about to be reached when the constellation consists of 24 operational satellites with six spare spacecraft. The diversity of satellite types and different orbital geometries require dealing with different types of perturbing forces acting on Galileo satellites. All of this is crucial in terms of unification of orbit determination strategy for the International GNSS Service (IGS, Dow et al. 2009). Multi-GNSS Pilot Project, which evolved from the Multi-GNSS Experiment (MGEX, Montenbruck et al. 2017a, b), set up the goal to integrate all the possible navigation systems. Galileo satellites orbit at a nominal altitude of about 29,600 km, therefore, the greatest non-gravitational perturbing force acting on Galileo satellites is the direct solar radiation pressure (SRP). However, indirect radiation, i.e., albedo, together with infrared earth radiation also cause significant orbit perturbations.

Direct solar radiation pressure modeling

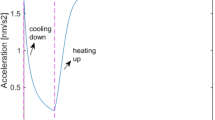

Direct SRP is the main non-gravitational source of accelerations acting on GNSS satellites. The accelerations reach the magnitude of 160 nm/s2 thus, when not absorbed, introduce perturbations at the level of 100 m over the time scales of one orbital revolution (Beutler and Mervart 2010). Coping with the direct SRP can be solved threefold by employing (1) analytical models, (2) semi-analytical or hybrid models with estimating parameters adopting to SRP perturbations, and (3) empirical models (Ziebart 2004).

Analytical models are based on dimensions and optical properties of the satellites, thus they are capable of describing the physical interaction between the SRP and the spacecraft. For the satellite bus which is covered by multilayer insulation for thermal protection, the re-radiation in the same direction may be considered as instantaneous. Hence, accelerations ab acting on a satellite bus due to SRP with immediate thermal re-radiation according to Lambert’s law can be described by the formula (Milani et al. 1987):

For the solar panels, the instantaneous re-radiation effect in the normal direction cannot be assumed, therefore for the accelerations asp due to absorbed as well as diffusely and specularly reflected photons are described by the formula:

In (1) and (2), c is the speed of light, A denotes an area of a single flat surface element, and m is the mass of the satellite element. An angle between the unit vector of the surface normal en and the unit vector of the direction of the illuminating source \( e_{ \odot } \) is described by θ. SRP results from the impulse transfer of the absorbed and emitted photons on the satellite’s surface illuminated by the sun. Fractions α, δ, and ρ describe absorbed, diffusely reflected, and secularly reflected photons, respectively (with α + δ + ρ = 1, Milani et al. 1987). In this study, we assume that the solar constant S equals 1367 W/m2 (Montenbruck et al. 2015c). However, the solar constant value has been revised based on re-analysis and re-calibration of satellite data by Dudok de Wit et al. (2017) who assessed its value at the level of 1361 W/m2. Nonetheless, the small difference between the two solar constant values will not affect the results due to the fact that they will be absorbed by the empirical parameters when estimated. Equations (1) and (2) comprise the basis for the analytical models which has been developed already at the beginning of the ‘90s when Fliegel et al. (1992) created the so-called ROCK models for the GPS satellites of Blocks II and IIA. The accelerations resulting from SRP were expressed as a Fourier expansion in the body-fixed frame coordinates X and Z, and an argument being the angle between the sun and the spacecraft’s Z-axis. The Y-bias has been reported in the ‘90s, which enforced the estimation of the scaling factor for the model acceleration. Both this, and further axis nomenclature used in this study, is consistent with the IGS conventions, and the description from Table 1, i.e., the + Z-axis pointing toward the earth center, thus the satellite illuminates the earth with its navigation signal, + X-axis points to hemisphere containing the sun, and the + Y-axis completes the right-handed orthogonal frame and is parallel to the rotation axis of the solar panels. For details, see Montenbruck et al. (2015a).

Equations (1) and (2) can also be used for the formulation of the so-called box-wing model which considers the satellite’s bus (the “box”) and the solar panels (the “wings”). Such models have been developed by Rodriguez-Solano et al. (2012) who created an adjustable box-wing model for GPS satellites. Apart from the aforementioned models, there is also a finite element representation and ray-tracing techniques which provide an even more accurate description of the satellite’s structure taking into account the mutual shadings and multiple reflections. Such analytical models have been developed for GPS Block IIR satellites (Li et al. 2018), for the old type of GLONASS satellites (Ziebart and Dare 2001), and for QZS-1 (Darugna et al. 2018).

Empirical models are based on parameter estimation, often to compensate deficiencies in a priori models. An empirical approach has been proposed by Beutler et al. (1994) who formulated the empirical CODE orbit model (ECOM). ECOM decomposes accelerations in three directions in the sun–satellite–earth frame (SSE), i.e., D—pointing from the satellite toward the sun, Y—along the solar panel rotation axis, and B—perpendicular to D and Y axes, completing the right-handed orthogonal frame. Due to the emerging of GNSS constellations, an extended ECOM2 was proposed by Arnold et al. (2015). The new ECOM2 considers the constant acceleration in each of the DYB directions, even periodic terms in direction D (currently, twice-per-revolution terms) and odd periodic parameters in direction B (currently, once-per-revolution terms). ECOM2 model is expressed as follows:

where Δu denotes an argument of latitude of the satellite with respect to the argument of latitude of the sun. The constant term in D absorbs the impact of the direct SRP on the solar panels and the mean SRP acting on the bus, including the solar wind. The constant terms Y and B absorb the Y-bias and B-bias, respectively. The biases occur due to the misalignment of the solar panels with reference to the sun position. Periodic cosine terms absorb variations of the direct SRP acting on satellite’s bus, whereas sine periodic terms may absorb thermal effects related to the delays in the heat re-radiation (Arnold et al. 2015). The addition of the even terms in direction D to the ECOM2 model significantly diminished the sun elongation-dependent systematic errors indicated by satellite laser ranging (SLR) residuals to microwave-based GLONASS precise orbits provided by the Center of Orbit Determination in Europe (CODE) (Sośnica et al. 2015). Prange et al. (2017) reported that the new ECOM2 is suitable not only for the GLONASS satellites but also for Galileo and QZSS. SLR residuals analysis performed by them indicates a significant reduction of the systematic dependency of SLR residuals on the sun elevation angle above the orbital plane. The median SLR offset for the Galileo satellites was reduced as well, from − 58 to − 47 mm. However, they considered neither albedo nor antenna thrust modeling. After considering both effects, the SLR residuals to the CODE orbits indicate an orbit accuracy with standard deviation at the level of 20 mm for Galileo-FOC when using observations only from selected high-performing SLR stations (Zajdel et al. 2017). As a result, if Galileo satellites were to be determined with sub-centimeter accuracy, one has to take into account a more sophisticated SRP approach. This is especially crucial when taking into consideration the current requirements imposed by the global geodetic observing system (GGOS, Plag and Pearlman 2009). In terms of the other navigation satellite systems, one can find several approaches which use a different set of the ECOM parameters, which is expected due to the different characteristic of different satellites. Such approaches can be found, e.g., for the BeiDou satellites in Liu et al. (2016) and for the Indian Regional Navigation Satellite System (IRNSS, Rajaiah et al. 2017).

The mixtures of the analytical and empirical approaches are the hybrid or semi-empirical SRP models. The extended ECOM model proposed by Springer et al. (1999) is based on a priori coefficients estimated in the processing. Bar-Sever and Kuang (2004) used the least squares method to compute a long time series of daily orbits provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to derive empirical orbit parameters which could serve as a priori parameters. In terms of the Galileo-IOV satellites, Montenbruck et al. (2015c) provided an a priori cuboid box-wing model based on the long-term set of Galileo-IOV observations. The cuboid model allowed for the decrease in the RMS of SLR residuals from 109 to 55 mm. Such a hybrid model has also been developed for the BeiDou Geostationary Earth Orbit satellites (Wang et al. 2018) and the very first satellite of the Japanese Quasi-Zenith Satellite System (QZSS), the QZS-1 (Montenbruck et al. 2017a). Duan et al. (2018) performed the evaluation of the optical properties for Galileo satellites and indicated only little corrections for the official parameters. Therefore, we present the a priori box-wing model for the Galileo satellites, based on the official parameters released by the European Global Navigation Satellite Systems Agency (GSA). In the case of the Galileo metadata usage, Duan et al. (2018), in the best case, obtained the RMS of SLR residuals at the level of 42 mm for the solution based on the box-wing model with the estimation of the classical ECOM. Li et al. (2019) performed the Galileo-FOC orbit determination using the box-wing model together with ECOM and obtained the STD of the SLR residuals at the level of 34 mm for the Galileo-FOC satellites. There is, however, little information in the literature, whether and how many ECOM parameters should still be estimated when using the a priori box-wing model.

Goal of this study

Our goal is to evaluate the Galileo precise orbit determination strategy which copes with SRP, albedo, the infrared earth radiation (IR), and the navigation antenna thrust. We perform the Galileo orbit solution for 200 days of 2017 in analytical, empirical, and hybrid approaches. We assess how the reduction of empirical parameters acts on the Galileo orbit solution when using the a priori box-wing model. Moreover, for the first time, we show the Z component of geocenter estimates together with their errors provided solely by the Galileo observations. We check whether the reduction of the estimated empirical parameters diminishes the error of the geocenter estimates which are correlated with the ECOM parameters and strongly depend on the satellite constellation geometry with respect to the sun.

Methodology

Owing to the fact that GSA released the metadata for the Galileo constellation, we have composed and implemented to the modified version of the Bernese GNSS Software 5.2 (Dach et al. 2015) the a priori box-wing whose assumptions for the SRP impact are consistent with those from Rodriguez-Solano et al. (2012). The box-wing model is implemented with the consideration of both the earth’s and the moon’s shadow including penumbra periods. This is crucial because ECOM parameters are set to 0 when the satellite enters the earth’s shadow. As a result, the box-wing model absorbs the acceleration which comes from, e.g., the infrared radiation.

We prepared 1-day Galileo orbit products based on the double-difference global GNSS solution. The orbit processing is consistent with the CODE-MGEX strategy (Prange et al. 2017). Processing details are provided in Table 1. We used the globally distributed network of 106 multi-GNSS stations (see Fig. 1).

In order to evaluate the impact of the box-wing model, we performed calculations in three variants which are different in terms of (1) the box-wing application, (2) estimation of the different set of the empirical orbit parameters and (3) usage of albedo, IR, and antenna thrust (see Table 2). Three main strategies are calculated, strategy “B” denotes the hybrid solution with the application of the box-wing model, albedo, IR and the antenna thrust modeling. The number in the strategy name denotes the number of additionally estimated empirical parameters. “0” denotes only the constant terms of the accelerations in DYB, “1” stands for the parameters used in ECOM model, and “2” represents the set of the latest ECOM2 parameters.

Strategies “E” are consistent with strategies “B”; however, the a priori box-wing model was not applied. The strategy “N2” considers the ECOM2 parameters without either the box-wing model or the application of the antenna thrust or albedo and IR modeling. Additionally, we tested the solution using solely the box-wing model, which is called “BB”.

The internal quality of the orbit is evaluated based on the boundary discontinuities for each consecutive 1-day orbital arc. Moreover, the orbit was checked independently using the SLR validation. Finally, we calculate the 5-day orbit predictions and check their quality and stability based on the comparison with the final post-processed orbit from the corresponding day. Eventually, we assess the impact of the particular solutions on the Z component of the geocenter coordinates.

Results

Now we present the result of the Galileo orbit strategies with particular attention to the box-wing model application and the reduction of the empirical parameters in the hybrid solutions. We check both the internal and external consistency of all the orbit determination strategies by the analysis of the orbit misclosures and the SLR residual analysis, respectively. Finally, we investigate the impact of the box-wing model application on the Z component of the geocenter estimates.

Orbit discontinuity analysis

The internal consistency of all solutions has been assessed based on the 1-day orbit discontinuities. Figure 2 shows that the solution based solely on the box-wing model is significantly worse than for the strategies which consider estimation of any set of the empirical parameters. Despite different approaches and considering different force models all the remaining solutions are consistent at a similar level apart from solutions BB and E1. The figure depicts the orbit discontinuities decomposed in the radial, along-track and cross-track directions. Apart from solutions BB and E1, the maximum absolute values of the discontinuities do not exceed 200 mm. The inter-quartile range (IQR) for the solution based on ECOM1 is significantly higher than for solutions based on ECOM2 (E2) and all the box-wing model-based solutions. The internal quality of theoretically the worst modeled solution, N2, is at a comparable level to both B1 and E2 solutions.

Orbit discontinuities for particular solutions decomposed in the radial, along-track, and cross-track components presented in the form of the box-plots. The bottom and the top line of the box indicate the first (Q1) and the third (Q3) quartile, respectively. The height of the box denotes the inter-quartile range (IQR). Top and bottom whisker indicate the value of Q3 + 1.5∙IQR and Q1 − 1.5∙IQR, respectively. Individual outliers are not shown

SLR residual analysis

The inferior quality of the solution N2 is visible when using the SLR technique as an independent validation tool (Fig. 3). SLR residual analysis is especially effective for the radial direction because it is based on the direct range measurements with low incidence angles at GNSS altitudes. As a result, it is well suited for the investigation of the systematic errors related to the orbit perturbing forces. It is clearly stated that the application of the antenna thrust, albedo, and IR diminishes the systematic offset by approximately 23–33 mm (see mean values for N2 and E2 in Table 3). However, when applying the box-wing model, systematic offset at the level of 15–16 mm appears for the Galileo-FOC satellites. Figure 3 illustrates SLR residuals for the particular Galileo types.

SLR residuals for the Galileo satellites decomposed into satellites types, Galileo-IOV, Galileo-FOC, and Galileo-FOC on eccentric orbits. The nomenclature of the box-plot is consistent with Fig. 2

The standard deviation (STD) in all the cases is at a similar level of 30 mm apart from the solution E1 for which the STD exceeds about 50 mm. The SLR residuals for the solution based solely on the box-wing model are less precise than for the box-wing based solutions in which the empirical parameters are estimated, especially for the Galileo-IOV satellites., i.e., the STD of SLR residuals reaches 42.8 mm for solution BB.

For all solutions, the Galileo-IOV satellites indicate a negative offset, even for the E2 solution. In contrast to the IOV generation, Galileo-FOC satellites indicate a positive offset. When analyzing SLR residuals illustrated in Fig. 3 one would deduce that the solution E2 provides one of the most reliable orbit results. However, when taking into consideration the STD for SLR residuals solely for the Galileo-FOC, the residuals for the hybrid solution are less scattered than for the solution E2, i.e., the STD of the SLR residuals for the solution E2 is at the level of 27.3 mm as compared to 25.0 mm for the solution B1.

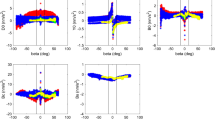

Moreover, when analyzing the SLR residuals as a function of the position of the satellite in the SSE frame for the solution E2, one can notice a significant increase in the SLR residuals when the |β| angle assumes values lower than 12.3°. Figure 4 presents the SLR residuals for three solutions, (1) consistent with CODE, i.e., the solution E2 (Fig. 4, top), (2) the hybrid solution B1 using box-wing model with the estimation of the limited set of empirical parameters, neglecting the periodic terms in the sun–satellite direction (Fig. 4, middle), (3) and the solution BB based solely on the box-wing model (Fig. 4, bottom). Despite an offset in the solution B1, the distribution of SLR residuals is significantly less dependent on the satellite positions in the SSE frame. The STD of the SLR residuals for the low β angle is diminished from 36.5 mm in the solution E2 to 24.7 mm in the solution B1, and 23.3 mm in the solution B0 for which the distribution of the SLR residuals is similar to that obtained for the solution B1. Although the solution BB is characterized with an offset of SLR residuals smaller by the factor of 2 than for the solution B1 for the Galileo-FOC satellites, the spread of the SLR residuals is significantly higher than for the box-wing solutions with an additional estimation of empirical parameters (B1). The box-wing solution BB, on the other hand, is less vulnerable relative to |β| angles below 12.3° than the solution E2, i.e., the STD of the SLR residuals reaches 31.5 mm for the solution BB.

SLR residuals for the Galileo-FOC satellites for solutions E2 (top), B1 (middle), and BB (bottom) as a function of the absolute height of the sun above the orbital plane (β) and the argument of latitude of the satellite with respect to the argument of latitude of the sun (Δu). All values are expressed in mm

To conclude, when employing the SLR validation, the box-wing provides the most precise orbit solutions, however, a small set of empirical orbit parameters has to be additionally estimated in order to diminish the STD of the SLR residuals, especially during the eclipsing periods with low |β| angles. Regarding ECOM2, the terms D2C and D2S can be neglected when using the box-wing model.

Quality of the orbit prediction

A reliable orbit solution ensures the stability of the orbit predictions. GNSS satellites transmit within the navigation signal information about the constellation almanac and the satellites’ positions as part of the broadcast ephemerides. According to IGS, the accuracy of the broadcast orbits equals approximately 1 m. The broadcast ephemerides are calculated on a daily routine by the ground segment of each GNSS provider. In our analysis, we provide the calculation of the 5-day Galileo orbit predictions and tested all solution strategies.

Figure 5 presents the box-plot illustrating the quality of the 5-day orbit predictions for the radial and cross-track components. As to internal consistency of solutions and the SLR residuals analysis, the solution E1 does not provide stable orbit predictions. The solutions E2 and N2 show similar results despite the usage of the different force models. It is not the matter of the same set of the empirical parameters being used in the solutions E2 and N2, because the solution B2 is also based on the ECOM2 and yet is characterized with the median value of the STD in the radial direction of 33 cm as compared to 45 and 44 cm for E2 and N2, respectively.

Five-day orbit prediction quality for the particular processing strategy for the radial (top) and cross-track components (bottom). The box-plots illustrate the STD (left) and RMS (right) of the predicted orbit positions. The nomenclature of the box-plot is consistent with Fig. 2

The fewer empirical parameters are estimated in the hybrid solution, the more stable the prediction becomes. The median value of the STD for the orbit predictions in the radial direction for the solution B1 equals 32 cm, with the variability of STD, i.e., IQR at the level of 39 cm as compared to 42 cm for the solution B2. On the other hand, the solution based on the box-wing model with the estimation of the constant acceleration terms (B0) is characterized with the median value of STD at the level of 47 cm in the radial direction despite a significantly lower IQR of the STD at the level of 30 cm. The cross-track component is predicted the most reliably. Here, the most reliable orbit predictions are provided by the solution B0, for which the median values of the STD equals 14 cm with the IQR at the level of 12 cm. The remaining box-wing solutions do not diverge from the B0 solution. However, in the solution BB, we neglect all the empirical parameters which absorb the accelerations resulting from, e.g., the solar wind (D0) or misalignment of the solar panel with reference to the sun (Y0).

As a result, the solution based solely on the box-wing model (BB) is insufficient in terms of the orbit predictions, i.e., the mean STD in the cross-track direction exceeds 22 cm for BB when compared to 14 cm for the solution B1. When analyzing the RMS values for the radial and cross-track components, all the values are only slightly higher than for the STD, thus their distance for the expected value, i.e., 0, is relatively small. The worst predicted is the along-track component (shown only for B1 in Fig. 6) for which for all the solutions the median value of the STD exceeds 2 m with the IQR at the level of 10–12 m.

The quality of all the components is illustrated in Fig. 6, where both the median STD and the RMS are depicted as a function of time expressed in the 12-h intervals. The median STD describes the internal accuracy of the orbit prediction, whereas the RMS describes the standard deviation from the expected value (i.e., the estimated orbits based on true observations). The internal accuracy of the orbit prediction is of moderate quality and does not exceed 0.4 m STD until 48 h in the along-track direction. The good prediction in the along-track direction is important in terms of the SLR tracking for the proper orientation of the SLR telescope. The RMS does not exceed 20 m even after 6 days. Moreover, the quality of the Galileo broadcast ephemerides which was checked by Montenbruck et al. (2015b) was at the level of 0.6 m 2.7 and 2.3 m in the radial, along-track, and cross-track direction, respectively. The orbit predictions calculated using the orbit solution B1 exceed the 2.7 m level of accuracy only after 48 h. As a result, such predictions based on the hybrid box-wing-empirical model may comprise an alternative for the broadcast ephemerides and could be uploaded to the operational constellation.

Impact of the box-wing model on the Z component of the geocenter coordinates

In the global geodetic solutions the suggested technique for the determination of the origin of the terrestrial reference frame is SLR owing to the sub-centimeter precision in the two-way range measurements between SLR stations and geodetic satellites (Otsubo et al. 2018) and the low vulnerability of geodetic satellites to the non-gravitational perturbing forces (Sośnica et al. 2014). As a result, the geocenter coordinates (GCCs) used in the current realization of the origin of the International Terrestrial Reference Frame (ITRF2014, Altamimi et al. 2016) are determined using SLR-derived time series.

The issues of GCC estimation from GNSS are well known (Wu et al. 2012; Meindl et al. 2013; Rebischung et al. 2014). The signal of the GNSS-derived geocenter is the result of the orbit modeling, as well as the ground station distribution and the sensitivity of the GNSS technique to the motion of the geocenter. As a result, the actually observed signal is usually called the “apparent geocenter coordinates” (Rebischung and Garayt 2013). The GCC time series derived using GNSS suffers from both the correlations with the empirical orbit parameters and the clocks which are simultaneously estimated during the processing as well as the mutual geometry of satellites in the SSE frame. Meindl et al. (2013) noticed the correlation between the Z component of GCC and D0 empirical parameter. On the other hand, Rebischung et al. (2014) indicated rather a minor impact of the single D0 term. The significant increase in the collinearity with GCC has been noticed only when simultaneously estimating D0 with the B1C, and B1S terms [see (3)]. The Z component of the estimated geocenter coordinates is especially sensitive to GNSS orbit modeling issues. Figure 7 illustrates the Z component of GCC, together with their errors, estimated for the solutions: E2, B2, B1, and B0. We also show the spectral analysis for both the estimated Z component of GCC and its formal errors (Fig. 8). We focus on GCC-Z component only, as it clearly shows the improvement when the box-wing model is applied in the orbit determination. The changes for GCC X and Y components are insignificant, thus not described here.

Figure 7 (bottom) shows how do the formal errors of GCC-Z component change in time. The pattern significantly differs for the particular solutions which are different in terms of the set of the empirical orbit parameters being estimated. The time series of the formal errors of the Z component clearly depends on the mutual orientation of the orbital planes with respect to the position of the sun (denoted as a β angle). For the solution E2 and B2, the formal errors increase when two planes have a similar orientation to the sun confirming the results reported by Scaramuzza et al. (2018) for the GLONASS constellation.

When neglecting the periodic D2C and D2S terms, i.e., in the solution B1, the error dependence on the satellite positions significantly diminishes and nearly disappears in the solution B0, which neglects also terms B1C and B2S, which is consistent with results of Rebischung et al. (2014). The GCC error for solution E2 and B2 is almost by the factor of 2 higher than for the other solutions. Nonetheless, the systematic offset of the error signal in the solution B0 is mitigated by a factor of 2, to the value of 1.3 mm, as compared to the solution B1. In summary, the consideration of the box-wing based orbit solution with the limited number of the empirical parameters significantly diminishes the formal error of the Z component of GCC and reduces its dependence on the SSE configuration and mutual orbital plane orientations.

Figure 8 (top) shows the spectral analysis of the time series presented in Fig. 7. When applying the box-wing model, we get rid of the peak of the 1/7 harmonic of the draconitic year in the E2 solution of the amplitude of 8 mm. The draconitic year equals 355.6 days for the Galileo satellites (Sośnica et al. 2018). However, when using the box-wing solutions we introduce another peak which corresponds to the 1/3 of the draconitic year of the Galileo satellites (Fig. 8, top). The characteristic peak exceeds the level of 10 mm for both B2 and B1 solutions, whereas for the solution B0 the peak does not exceed the value of 6 mm. Moreover, the usage of the solution B2 causes the occurrence of the 1/5 peak whose amplitude is below 5 mm. The formal geocenter errors depend on the constellation geometry with respect to the sun (Fig. 7, bottom). As a result, the characteristic periods occur when the orientation of two Galileo planes with respect to the sun direction is the same, i.e., up to six times for every Galileo draconitic year. These periods are irregular because every orbital plane has a different orientation with respect to the ecliptic, despite the same inclination angle with respect to the equator. Moreover, the orientation with respect to the ecliptic slowly changes due to the revolution of the Galileo nodal point with the period of 37 years. The characteristic peaks in the error of the Z component of the geocenter do not exceed 0.8 mm and are mostly visible for the solutions B2 and E2 due to the same set of empirical parameters applied. The peaks are significantly diminished for the solution B1 and almost vanish for B0. To conclude, the solution B0 significantly diminishes the dependence on the mutual orbital plane orientations and GCC errors as well as the magnitude of the spurious draconitic signal in the Z component, due to the fact that we avoid the correlation with the simultaneously estimated periodic parameters in the D and B directions. Moreover, the B0 solution suppresses the characteristic peak equal to 1/7 of the draconitic year, whereas the introduced peak, which corresponds to 1/3 of the draconitic year, is by about 1 mm lower than the suspended one. However, the test study should be extended to a longer time series to fully evaluate its geophysical interpretation.

Discussion and summary

Based on the metadata for the Galileo satellite we composed the box-wing model for the absorption of SRP, albedo, and IR. In order to validate the effectiveness of the box-wing model and to formulate the optimal orbit determination strategy, we performed a series of processing strategies. We checked both the internal and external consistency of all solutions using the 1-day orbital arc discontinuities and the SLR residual analyses, respectively.

The internal quality of all solutions is at a similar level, apart from the solution based solely of the box-wing model (BB), which is significantly worse. The external quality analysis indicated that there is a systematic offset in SLR residuals depending on the satellite type, i.e., the IOV satellites are characterized by the negative offset whereas the FOC satellites are characterized by the positive offset. However, the solutions based on the box-wing model with the simultaneous estimation of the empirical parameters (solutions B0, B1, and B2) are characterized with slightly lower STD of the SLR residuals to the FOC satellites than the solution based on the ECOM2 model (E2). The real supremacy of the box-wing “B” solutions is visible when taking into consideration the SLR residuals as a function of Δu and β angles. A significant decrease in the SLR residuals is visible for solutions “B” especially for |β| angles < 12.3°. For such a geometry, the STD of SLR residuals is mitigated from 36.5 mm for the solution E2, to 24.7 mm for the solution B1, and to 23.3 mm for the solution B0. The hybrid solutions B0 and B1 provide the Galileo-FOC orbit accuracy, as measured by SLR, at the level of 25.3 and 25.0 mm, respectively, which is by 9 mm better than obtained by Li et al. (2019) and by 17 mm better than given by Duan et al. (2018). We also checked the stability of the orbit predictions calculated based on particular solutions. The most stable predictions are derived from the hybrid solutions B0 and B1 which suggests that the fewer empirical parameters are estimated in the hybrid solution the better. Based on the hybrid solution B1, one can provide orbit prediction with the accuracy better than 3 m for at least 48 h.

Finally, we took a closer look at the geocenter Z component estimates provided for the first time using only Galileo observations. The formal error of the Z component of GCC, which is dependent on the set of the estimated ECOM parameters and the geometry of the Galileo planes with respect to the sun, significantly diminishes when reducing the ECOM2 by the terms D2C and D2S, and almost disappears when estimating only the constant DYB terms.

The empirical orbit models do not fully absorb the direct SRP, especially during the eclipsing periods, which is due to the fact that the empirical models are truncated and neglect the higher-order perturbation terms. Moreover, the correlations between the periodic terms of the empirical models with global geodetic parameters, including GCC, deteriorate the estimates of global parameters. The analytical models, on the other hand, reflect most of the physical interactions between solar radiation pressure and particular components of the satellites. However, the analytical models are insufficient for compensating all changes of external conditions, such as solar wind, or changes of satellite surface properties over time, or Y-biases and thermal effects, which are difficult to account for in simplified box-wing models. Therefore, the hybrid model considering the a priori box-wing model with the estimation of the minimized set of the empirical parameters provides the optimal strategy for precise orbit determination based on the box-wing models constructed using the Galileo metadata. However, the set of the estimated empirical parameters should be reduced in order to obtain the precise orbit solution and stable-in-time orbit predictions. The reduction of the number of empirical parameters diminishes the systematic error of the Z component of the GCC through reducing the number of estimated parameters, thus stabilizes the processing. As a result, the most reliable Galileo orbit results from this study are provided by strategy B0, which considers the box-wing model and only the estimated constant accelerations in DYB directions, and the strategy B1, in which the box-wing model is used with estimating periodic accelerations in the B direction together with constant DYB accelerations.

References

Altamimi Z, Rebischung P, Métivier L, Collilieux X (2016) ITRF2014: a new release of the international terrestrial reference frame modeling nonlinear station motions: ITRF2014. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 121(8):6109–6131. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JB013098

Arnold D, Meindl M, Beutler G, Schaer S, Lutz S, Prange L, Sośnica K, Mevart L, Jäggi A (2015) CODE’s new solar radiation pressure model for GNSS orbit determination. J Geod 89(8):775–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-015-0814-4

Bar-Sever Y, Kuang D (2004) New empirically derived solar radiation pressure model for GPS satellites. Interplanetary network progress report. vol 42–159. http://ipnpr.jpl.nasa.gov/progress_report/42-159/title.htm

Beutler G, Mervart L (2010) Methods of celestial mechanics, vol 1: physical, mathematical, and numerical principles. Springer, Berlin

Beutler G, Brockmann E, Gurtner W (1994) Extended orbit modeling techniques at the CODE processing center of the International GPS Service for Geodynamics (IGS): theory and initial results. Manuscr Geod 19(6):367–386

Dach R, Lutz S, Walser P, Fridez R (eds) (2015) Bernese GNSS software version 5.2. https://doi.org/10.7892/boris.72297

Darugna F, Steigenberger P, Montenbruck O, Casotto S (2018) Ray-tracing solar radiation pressure modeling for QZS-1. Adv Space Res 62(4):935–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2018.05.036

Dow JM, Neilan RE, Rizos C (2009) The international GNSS service in a changing landscape of global navigation satellite systems. J Geod 83(3–4):191–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-008-0300-3

Duan B, Hugentobler U, Selmke I (2018) The adjusted optical properties for Galileo/BeiDou-2/QZS-1 satellites and initial results on BeiDou-3e and QZS-2 satellites. Adv Space Res 63(5):1803–1812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2018.11.007

Dudok de Wit T, Kopp G, Fröhlich C, Schöll M (2017) Methodology to create a new total solar irradiance record: making a composite out of multiple data records: making a composite. Geophys Res Lett 44(3):1196–1203. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL071866

Fliegel HF, Gallini TE, Swift ER (1992) Global positioning system radiation force model for geodetic applications. J Geophys Res 97(B1):559. https://doi.org/10.1029/91JB02564

Li Z, Ziebart M, Bhattarai S, Bhattarai S, Harrison D, Grey S (2018) Fast solar radiation pressure modelling with ray tracing and multiple reflections. Adv Space Res 61(9):2352–2365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2018.02.019

Li X, Yuan Y, Huang J, Zhu Y, Wu J, Xiong Y, Li X, Zhang K (2019) Galileo and QZSS precise orbit and clock determination using new satellite metadata. J Geod. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-019-01230-4

Liu J, Gu D, Ju B, Shen Z, Lai Y, Yi D (2016) A new empirical solar radiation pressure model for BeiDou GEO satellites. Adv Space Res 57(1):234–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2015.10.043

Meindl M, Beutler G, Thaller D, Dach R, Jäggi A (2013) Geocenter coordinates estimated from GNSS data as viewed by perturbation theory. Adv Space Res 51(7):1047–1064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2012.10.026

Milani A, Nobili AM, Farinella P (1987) Non-gravitational perturbations and satellite geodesy. A. Hilger, Bristol

Montenbruck O, Günther C, Graf S, Fernandez MG, Furthner J, Kuhlen H (2006) GIOVE-A initial signal analysis. GPS Solut 10(2):146–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-006-0027-7

Montenbruck O, Schmid R, Mercier F, Steigenberger P, Noll C, Fatkulin R, Kogure S, Ganeshan AS (2015a) GNSS satellite geometry and attitude models. Adv Space Res 56(6):1015–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2015.06.019

Montenbruck O, Steigenberger P, Hauschild A (2015b) Broadcast versus precise ephemerides: a multi-GNSS perspective. GPS Solut 19(2):321–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-014-0390-8

Montenbruck O, Steigenberger P, Hugentobler U (2015c) Enhanced solar radiation pressure modeling for Galileo satellites. J Geod 89(3):283–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-014-0774-0

Montenbruck O, Steigenberger P, Darugna F (2017a) Semi-analytical solar radiation pressure modeling for QZS-1 orbit-normal and yaw-steering attitude. Adv Space Res 59(8):2088–2100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2017.01.036

Montenbruck O, Steigenberger P, Prange L et al (2017b) The multi-GNSS experiment (MGEX) of the international GNSS service (IGS)—achievements, prospects and challenges. Adv Space Res 59(7):1671–1697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2017.01.011

Otsubo T, Müller H, Pavlis EC, Torrence MH, Thaller D, Glotov VD, Wang X, Sośnica K, Meyer U, Wilkinson MJ (2018) Rapid response quality control service for the laser ranging tracking network. J Geod. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-018-1197-0

Plag H-P, Pearlman M (eds) (2009) Global Geodetic Observing System: meeting the requirements of a global society on a changing planet in 2020. Springer, Berlin

Prange L, Orliac E, Dach R, Arnold D, Beutler G, Schaer S, Jäggi A (2017) CODE’s five-system orbit and clock solution—the challenges of multi-GNSS data analysis. J Geod 91(4):345–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-016-0968-8

Rajaiah K, Manamohan K, Nirmala S, Ratnakara SC (2017) Modified empirical solar radiation pressure model for IRNSS constellation. Adv Space Res 60(10):2146–2154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2017.08.020

Rebischung P, Garayt B (2013) Recent Results from the IGS Terrestrial Frame Combinations. In: Altamimi Z, Collilieux X (eds) Reference Frames for Applications in Geosciences. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 69–74

Rebischung P, Altamimi Z, Springer T (2014) A collinearity diagnosis of the GNSS geocenter determination. J Geod 88(1):65–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-013-0669-5

Rodriguez-Solano CJ, Hugentobler U, Steigenberger P (2012) Adjustable box-wing model for solar radiation pressure impacting GPS satellites. Adv Space Res 49(7):1113–1128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2012.01.016

Scaramuzza S, Dach R, Beutler G, Arnold D, Sušnik A, Jäggi A (2018) Dependency of geodynamic parameters on the GNSS constellation. J Geod 92(1):93–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-017-1047-5

Sośnica K, Jäggi A, Thaller D, Beutler G, Dach R (2014) Contribution of Starlette, Stella, and AJISAI to the SLR-derived global reference frame. J Geod 88(8):789–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-014-0722-z

Sośnica K, Thaller D, Dach R, Steigenberger P, Beutler G, Arnold D, Jäggi A (2015) Satellite laser ranging to GPS and GLONASS. J Geod 89(7):725–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-015-0810-8

Sośnica K, Prange L, Kaźmierski K, Bury G, Drożdżewski M, Zajdel R (2018) Validation of Galileo orbits using SLR with a focus on satellites launched into incorrect orbital planes. J Geod 92(2):131–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-017-1050-x

Springer TA, Beutler G, Rothacher M (1999) A new solar radiation pressure model for GPS satellites. GPS Solut 2(3):50–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00012757

Steigenberger P, Montenbruck O (2017) Galileo status: orbits, clocks, and positioning. GPS Solut 21(2):319–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-016-0566-5

Steigenberger P, Hugentobler U, Montenbruck O, Hauschild A (2011) Precise orbit determination of GIOVE-B based on the CONGO network. J Geod 85(6):357–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-011-0443-5

Wang C, Guo J, Zhao Q, Liu J (2018) Empirically derived model of solar radiation pressure for BeiDou GEO satellites. J Geod. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-018-1199-y

Wielicki BA, Barkstrom BR, Harrison EF, Lee RB, Smith GL, Cooper JE (1996) Clouds and the earth’s radiant energy system (CERES): an earth observing system experiment. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 77(5):853–868. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077%3c0853:CATERE%3e2.0.CO;2

Wu X, Ray J, van Dam T (2012) Geocenter motion and its geodetic and geophysical implications. J Geodyn 58:44–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jog.2012.01.007

Zajdel R, Sośnica K, Bury G (2017) A new online service for the validation of multi-GNSS orbits using SLR. Remote Sens 9(10):1049. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9101049

Ziebart M (2004) Generalized analytical solar radiation pressure modeling algorithm for spacecraft of complex shape. J Spacecr Rockets 41(5):840–848. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.13097

Ziebart M, Dare P (2001) Analytical solar radiation pressure modelling for GLONASS using a pixel array. J Geod 75(11):587–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001900000136

Acknowledgements

The IGS MGEX is acknowledged for providing multi-GNSS data. Both GNSS and SLR observations have been obtained from the Crustal Dynamics Data Information System. This work was realized in the frame of the projects funded by the Polish National Science Centre (NCN). G. Bury is supported by the PRELUDIUM grant UMO-2018/29/N/ST10/00289; K. Sośnica and R. Zajdel are supported by the OPUS grant UMO-2018/29/B/ST10/00382. We also thank the Wroclaw Center of Networking and Supercomputing computational grant using MATLAB Software License No: 101979 (http://www.wcss.wroc.pl).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bury, G., Zajdel, R. & Sośnica, K. Accounting for perturbing forces acting on Galileo using a box-wing model. GPS Solut 23, 74 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-019-0860-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-019-0860-0