Abstract

Using data on Chinese outward direct investment and migrant stocks in 96 countries from 2003 to 2014, we find that migrant networks have a positive and significant impact on cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A), but not on greenfield investment. The migrant network effect is more pronounced for multinationals with less experience in the host country, especially for initial entrants that face greater firm, industry, and country-level information frictions. These results are robust to various estimation methods, including an instrumental variable approach that addresses potential endogeneity concerns. Our findings demonstrate the importance of knowledge spillovers from migrant networks to multinationals for facilitating entry into new markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Earlier work includes Gould (1994), Head and Ries (1998), Combes et al. (2005), and Dunlevy (2006), who study the interaction of social networks and trade for US, Canada, France, and US, respectively. Some recent studies demonstrate causality by exploiting quasi-natural experiments (e.g., Steingress, 2018; Cohen et al., 2017; Parsons & Vézina, 2018). In addition, Burchardi and Hassan (2013) study the economic performance of West Germans by examining their social ties to East Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Other work in this area includes Kugler and Rapoport (2007) and Bhattacharya and Groznik (2008). Gao (2003) and Tong (2005) show that overseas Chinese ethnic networks have a positive correlation with Chinese inward FDI and bilateral investment, respectively. Huang et al. (2013) also analyze Chinese inward FDI, but focus on the performance of industrial firms with investment originating from ethnically Chinese economies (Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan) versus other countries.

Transaction values are not always reported due to confidentiality, so we mainly focus on the extensive margin and the counts of M&A deals. UNCTAD (2017) also maintains a database of (non-bilateral) cross-border M&A purchases at the country level. For both the number and value of Chinese M&A purchases, SDC Platinum and UNCTAD (2017) are highly correlated at 0.91 and 0.85, respectively. SDC Platinum captures 38 to 80% of the number of M&A deals annually in UNCTAD (2017), and 42 to 276% of the value.

As stated in database documentation: “Most of the data used to estimate the international migrant stock by country or area were obtained from population censuses. Additionally, population registers and nationally representative surveys provided information on the number and composition of international migrants. In estimating the international migrant stock, international migrants have been equated with the foreign-born population whenever this information is available, which is the case in most countries or areas.” More information is available at http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates15.shtml. Gao (2003) and Tong (2005) study the relationship between Chinese ethnic networks abroad and aggregate FDI using data on ethnic Chinese populations in 1990. For the overlapping year of 1990, the correlation between the population of ethnic Chinese and Chinese migrants from the UN database is high (0.68).

The other SAR of China, Macau, and tax havens like British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands are excluded because missing data on the control variables.

Although the M&A data are available at the deal level, we are interested in the overall pattern of FDI flows and not just the size of the investment project for individual firms. Hence, we aggregate the M&A data by host country as the outcome variable. However, the detailed deal-level information allows us to decompose M&A by different characteristics and explore the channels through which migrant networks facilitate foreign investment.

Standard errors are clustered by host country for the linear and Poisson models to allow for the correlation of error terms across years within each destination. For the negative binomial model, the estimation of clustered standard errors in Stata is not currently feasible with the CRE approach (see the documentation of the xtnbreg command). However, as noted by Cameron and Trivedi (2009, p. 627), using the negative binomial model “may lead to improved efficiency in estimation and a default estimate of the VCE ([variance-covariance matrix of the estimates]) that should be much closer to the cluster-robust estimate of the VCE, unlike the Poisson panel commands.”

We found that directly applying the method of Burchardi et al. (2019) here yields extreme predictions of migrant stocks. This is in part due to the decreasing stocks observed in some countries, so that their migrant stocks, which were already small to begin with, turned negative in the predictions.

While the UN and World Bank datasets are not identical, the correlation between them is extremely high for the overlapping years of 1990 and 2000 at 0.98.

Although Chinese outward investment only rises significantly at the turn of the 21st century, the overseas Chinese community had been growing long before that, in particular, after restrictions on emigration were lifted in 1860 (Skeldon 1996). Notable examples of mass migration from China can be traced to labor shortages, including the gold rush in US and Australia, and the development of British colonies in Southeast Asia. Due to such labor market shocks, communities were established, forming the Chinese diasporas observed today.

We are also unable to reject the null hypothesis of the overidentification test when the predicted migrant network and, for example, the destination pull factor are used as instruments.

We confirm our regression results are also robust when we change the equity threshold of the global ultimate owner to 50.01%.

See Annex Table 8 from (UNCTAD 2017).

References

Abel, G. J., & Cohen, J. E. (2019). Bilateral international migration flow estimates for 200 countries. Scientific Data, 6, 82.

Aizenman, J., Jinjarak, Y., & Zheng, H. (2018). Chinese outwards mercantilism—The art and practice of bundling. Journal of International Money and Finance, 86, 31–49.

Allison, P. D. (2005). Fixed effects regression methods for longitudinal data using SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute.

Azemar, C., Darby, J., Desbordes, R., & Wooton, I. (2012). Market familiarity and the location of South and North MNEs. Economics& Politics, 24(3), 307–345.

Bartik, T. J. (1991, November). Who benefits from state and local economic development policies? Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, number wbsle. Books from Upjohn Press, W.E.

Bekaert, G., Harvey, C. R., & Lundblad, C. (2004). Does financial liberalization spur growth? Journal of Financial Economics, 77, 3–55.

Bénassy-Quéré, A., Coupet, M., & Mayer, T. (2007). Institutional determinants of foreign direct investment. World Economy, 30(5), 764–782.

Bertrand, O., Hakkala, K., Nilsson, P.-J. Norbäck., & Persson, L. (2012). Should countries block foreign takeovers of R&D champions and promote greenfield entry. Canadian Journal of Economics, 45(3), 1083–1124.

Bhattacharya, U., & Groznik, P. (2008). Melting pot or salad bowl: Some evidence from U.S. investments abroad. Journal of Financial Markets, 11(3), 228–258.

Bisztray, M., Koren, M., & Szeidl, A. (2018). Learning to import from your peers. Journal of International Economics, 115, 242–258.

Blonigen, B.A., & Lee, D. (2016). Heterogeneous frictional costs across industries in cross-border mergers and acquisitions. NBER Working Papers 22546.

Blonigen, B. A., & Piger, J. (2014). Determinants of foreign direct investment. Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(3), 775–812.

Buch, C. M., Kleinert, J., & Toubal, F. (2006). Where enterprises lead, people follow? Links between migration and FDI in Germany. European Economic Review, 50(8), 2017–2036.

Burchardi, K. B., Chaney, T., & Hassan, T. A. (2019). Migrants, ancestors, and foreign investments. Review of Economic Studies, 86(4), 1448–1486.

Burchardi, K. B., & Hassan, T. A. (2013). The economic impact of social ties: Evidence from German reunification. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(3), 1219–1271.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2009). Microeconometrics using Stata. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2013). Regression analysis of count data (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Chaney, T. (2014). The network structure of international trade. American Economic Review, 104(11), 3600–3634.

Chang, P.-l. (2014). Complementarity in institutional quality in bilateral FDI flows. SMU Economics & Statistics Working Paper Series, Paper No. 20-2014.

Chen, W., & Tang, H. (2014). The dragon is flying west: Micro-level evidence of Chinese outward direct investment. Asian Development Review, 31(2), 109–140.

Chen, C., Tian, W., & Yu, M. (2019). Outward FDI and domestic input distortions: Evidence from Chinese firms. Economic Journal, 129, 3025–3057.

Cheung, Y.-W., & Qian, X. (2009). Empirics of China’s outward direct investment. Pacific Economic Review, 14(3), 312–641.

China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT) (2015). Survey on Chinese enterprises’ outbound investment and operation in 2012. China Council for the Promotion of International Trade.

Cohen, L., Gurun, U. G., & Malloy, C. (2017). Resident networks and corporate connections: Evidence from World War II internment camps. Journal of Finance, 72(1), 207–248.

Combes, P.-P., Lafourcadea, M., & Mayer, T. (2005). The trade-creating effects of business and social networks: Evidence from France. Journal of International Economics, 66(1), 1–29.

Davies, R. B., Desbordes, R., & Ray, A. (2018). Greenfield versus merger & acquisition FDI: Same wine, different bottles? Canadian Journal of Economics, 51(4), 1151–1190.

de Sousa, J. (2012). The currency union effect on trade is decreasing over time. Economics Letters, 117(3), 917–920.

Desbordes, R., & Wei, S.-J. (2017). The effects of financial development on foreign direct investment. Journal of International Economics, 127, 153–168.

di Giovanni, J. (2005). What drives capital flows? The case of cross-border M&A activity and financial deepening. Journal of International Economics, 65, 127–149.

Dunlevy, J. A. (2006). The influence of corruption and language on the protrade effect of immigrants: Evidence from the American states. Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(1), 182–186.

Erel, I., Liao, R. C., & Weisbach, M. S. (2012). Determinants of cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Finance, 67(3), 1045–1082.

Fernandes, A. P., & Tang, H. (2014). Learning to export from neighbors. Journal of International Economics, 94(1), 67–84.

Gao, T. (2003). Ethnic Chinese networks and international investment: Evidence from inward FDI in China. Journal of Asian Economics, 14(4), 611–629.

Goldsmith-Pinkham, P., Sorkin, I., & Swift, H. (2020). Bartik instruments: What, when, why, and how. American Economic Review, 110(8), 2586–2624.

Gould, D. M. (1994). Immigrant links to the home country: Empirical implications for U.S. bilateral trade flows. Review of Economics and Statistics, 76(2), 302–316.

Greene, W. H. (2012). Econometric analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Gwartney, J., Lawson, R., & Hall, J. (2015). 2015 Economic Freedom Dataset, published in Economic Freedom of the World: 2015 Annual Report. http://www.freetheworld.com/datasets_efw.html

Hausman, J. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46(6), 1251–1271.

Head, K., & Ries, J. (1998). Immigration and trade creation: Econometric evidence from Canada. Canadian Journal of Economics, 31(1), 47–62.

Head, K., & Ries, J. (2008). FDI as an outcome of the market for corporate control: Theory and evidence. Journal of International Economics, 74, 2–20.

Huang, Y., Jin, L., & Qian, Y. (2013). Does ethnicity pay? Evidence from overseas Chinese FDI in China. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(3), 868–883.

Huang, J., & Kisgen, D. J. (2013). Gender and corporate finance: Are male executives overconfident relative to female executives? Journal of Financial Economics, 108(3), 822–839.

Huang, Y., & Wang, B. (2013). Investing overseas without moving factories abroad: The case of Chinese outward direct investment. Asian Development Review, 30(1), 85–107.

Javorcik, B. S., Özden, Ç., Spatareanu, M., & Neagu, C. (2011). Migrant networks and foreign direct investment. Journal of Development Economics, 94, 231–241.

Joshi, R., & Wooldridge, J. M. (2019). Correlated random effects models with endogenous explanatory variables and unbalanced panels. Annals of Economics and Statistics, 134, 243–268.

Kamal, F., & Sundaram, A. (2016). Buyer-seller relationships in international trade: Do your neighbors matter? Journal of International Economics, 102, 128–140.

Kugler, M., & Rapoport, H. (2007). International labor and capital flows: Complements or substitutes? Economic Letters, 94(2), 155–162.

Mundlak, Y. (1978). On the pooling of time series and cross section data. Econometrica, 46(1), 69–85.

Ottaviano, G. I., Peri, G., & Wright, G. C. (2018). Immigration, trade and productivity in services: Evidence from U.K. firms. Journal of International Economics, 112, 88–108.

Papke, L. E., & Wooldridge, J. M. (2008). Panel data methods for fractional response variables with an application to test pass rates. Journal of Econometrics, 145(1–2), 121–133.

Parsons, C., & Vézina, P.-L. (2018). Migrant networks and trade: The Vietnamese boat people as a natural experiment. Economic Journal, 128(612), 210–234.

Rauch, J. E. (2001). Business and social networks in international trade. Journal of Economic Literature, 39(4), 1177–1203.

Rauch, J. E., & Trindade, V. (2002). Ethnic Chinese networks in international trade. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(1), 116–130.

Rossi, S., & Volpin, P. F. (2004). Cross-country determinants of mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics, 74, 277–304.

Skeldon, R. (1996). Migration from China. Journal of International Affairs, 49(2), 434–455.

Steingress, W. (2018). The causal impact of migration on US trade: Evidence from a natural experiment. Canadian Journal of Economics, 51(4), 1312–1338.

Tong, S. Y. (2005). Ethnic networks in FDI and the impact of institutional development. Review of Development Economics, 9(4), 563–580.

UNCTAD (2014). World investment report. New York.

UNCTAD (2017). World investment report. New York.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2015). Control function methods in applied econometrics. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 420–445.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2019). Correlated random effects models with unbalanced panels. Journal of Econometrics, 211, 137–150.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The paper has also benefited tremendously from the comments and suggestions of two anonymous referees. The authors are also grateful for the suggestions provided by Yi Lu, Han Qi, Liugang Sheng, Heiwai Tang, Beata Javorcik, and participants of the seminars at Baptist University, Lingnan University, Nanyang Technological University, the Conference on Trade and Development at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and the Midwest Trade Conference.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Definitions of regulatory barriers (Gwartney et al., 2015)

This database covers five areas of economic freedom: (1) Size of government, (2) Legal system and property rights, (3) Sound money, (4) Freedom to trade internationally, (5) Regulation. Our analysis utilizes the following categories related to regulatory barriers and restrictions:

-

Regulation index (Area 5): An average index is constructed from the indices of: (A) Credit market regulations, (B) Labor market regulations, and (C) Business regulations.

-

Business regulations (component of Area 5 (Regulation)): An average index is constructed form the indices of 6 subcomponents: (i) Administrative requirements, (ii) Bureaucracy costs, (iii) Starting a business, (iv) Extra payments/bribes/favoritism, (v) Licensing restrictions. (vi) Cost of tax compliance.

-

Bribes, favoritism (subcomponent (C)(iv) of Area 5 (Regulation)): Based on the Global Competitiveness Report questions: (1) “In your industry, how commonly would you estimate that firms make undocumented extra payments or bribes connected with the following: Import and export permits; Connection to public utilities (e.g., telephone or electricity); Annual tax payments; Awarding of public contracts (investment projects); Getting favorable judicial decisions. Common (= 1), Never occur (= 7)”. (2) “Do illegal payments aimed at influencing government policies, laws or regulations have an impact on companies in your country? 1 = Yes, significant negative impact, 7 = No, no impact at all”. (3) “To what extent do government officials in your country show favoritism to well-connected firms and individuals when deciding upon policies and contracts? 1 = Always show favoritism, 7 = Never show favoritism”.

-

Hiring and firing regulations (subcomponent (B)(ii) of Area 5 (Regulation)): Based on the Global Competitiveness Report question: “The hiring and firing of workers is impeded by regulations (= 1) or flexibly determined by employers (= 7)”.

-

Credit market regulations (component of Area 5 (Regulation)): An average index is constructed from the indices of 3 subcomponents: (i) Ownership of banks, (ii) Private sector credit, (iii) Interest rate controls/negative real interest rates.

-

Foreign ownership restrictions (subcomponent (D)(i) of Area 4 (Freedom to trade internationally)): Based on the following questions from the Global Competitiveness Report: (1) “How prevalent is foreign ownership of companies in your country? 1 = Very rare, 7 = Highly prevalent”; (2) “How restrictive are regulations in your country relating to international capital flows? 1 = Highly restrictive, 7 = Not restrictive at all” (Fig. 2 and Tables 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14).

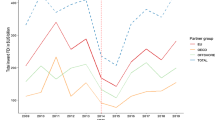

Outward greenfield FDI and M&A from a developing countries and transition economies; b developed economies. Source: UNCTAD (2017)

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, J.M.L., Zheng, H. FDI on the move: cross-border M&A and migrant networks. Rev World Econ 158, 947–985 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-021-00450-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-021-00450-1

Keywords

- Chinese migrant networks

- Cross-border mergers and acquisitions

- Foreign direct investment

- Information barriers

- Greenfield