Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic, and the associated confinement, imposed a novel personal and social context for university students; nevertheless, few studies have addressed the effects of this on distance university students. Indeed, defining the needs of these students under such unique circumstances will allow them to receive the support necessary to effectively reduce their perceived stress and improve their academic achievement. A predictive model was designed to examine the direct effects of the variables’ age and perceived study time on stress and academic achievement in students in an online learning context, as well as to assess the indirect effects through the mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Using path analysis, the model was tested on a sample of 1030 undergraduate students between 18 and 60 years old enrolled on a psychology degree course at the UNED (National Distance Learning University of Spain). The model provides a good fit to the data, confirming the mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Perceived study time is a factor negatively associated with stress and positively with academic achievement. However, it appeared that age was not related to academic achievement, indicating that academic self-efficacy had no mediating effect on these two variables. Academic self-efficacy is a mediator and protective factor in challenging times like the COVID-19 pandemic. These results may contribute to the design of educational and clinical interventions for students at an online learning university over an extended age range.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and the associated quarantine measures significantly affected the lives of all individuals in distinct circumstances (Brooks et al., 2020), as well as the mental health of people of different ages (Justo-Alonso et al., 2020). Governments implemented different measures to contain the virus and reduce the number of positive cases, such as lockdowns and isolation. In Spain, the period of confinement started on March 15, 2020, and the state of alarm ended on June 21, 2020 (Gobierno de España, 2020, 2023). Like many other countries, the quarantine measures imposed on the population implied radical changes in lifestyle, with fundamental restrictions on mobility, which had an important impact on the daily activities and psychosocial situation of individuals (Brooks et al., 2020; Chu et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Rey et al., 2020). Indeed, the pandemic and the related restrictions had a significant impact on mental health, inducing uncertainty (Bakioğlu et al., 2020; Ruiz-Robledillo et al., 2022), and increasing the levels of stress, anxiety, and depression in individuals of different ages and conditions (González-Sanguino et al., 2020; Odriozola-González et al., 2022; Sandín et al., 2021). Due to the COVID-19 quarantine, universities worldwide announced closures and restrictions on applications, and there was an abrupt transition from in-class lectures to online learning (Ali, 2020; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2020). University students and educators have had to adapt quickly to these changes in teaching methodology (Pokhrel & Chhetri, 2021; Tasso et al., 2021), using hybrid models or fully online teaching (Faura-Martínez et al., 2022). These urgent changes led to emergency online learning (Hodges et al., 2020), which cannot be equated in terms of planning, development, and experience with programs specifically designed to be taught online (Talsma et al., 2021). Online learning methodology relies on meticulous instructional design and planning, following a systematic model, and it may be considered a different experience from courses offered online in response to a sudden crisis (Hodges et al., 2020). Indeed, distance university courses taught with online methodology before the COVID-19 outbreak did not change substantially, involving virtual courses, online study materials, and communication forums. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, face-to-face activities like exams were also cancelled to comply with social distancing measures and they were carried out online (Aristeidou & Cross, 2021).

Perceived available study time in university students during the COVID-19 restrictions

In university students, the lockdown measures had an impact on the perception of their available study time and their capacity to organize their studies. During the pandemic, many students had to take on new responsibilities within the family, such as caring for family members or working to help financially, which decreased the time they could dedicate to their university work (Keyserlingk et al. 2022). Previous studies showed that academic demands can generate stress in students, particularly when it becomes difficult to balance study, work, and home commitments (Birbeck et al., 2021). High levels of uncertainty are associated with academic stress (Clabaugh et al., 2021), such that a perception of having less time to study can be an additional stressor in students, even in students at online distance universities (Aristeidou & Cross, 2021). Indeed, a longitudinal study showed that university students who lacked adequate time and energy for study experienced higher levels of psychological distress (Keyserlingk et al. 2022), suggesting that students may have faced additional challenges during the pandemic and that they may not have had sufficient personal resources to effectively cope with these.

The COVID-19 restrictions may not only negatively influence the psychological health of students but also their academic performance. Changes and uncertainty originating from the COVID-19 restrictions may affect academic achievement, although the true nature of this impact needs to be clarified. Thus, university students’ performance during the spread of COVID-19 might vary depending on the design and objective of the study (Aguilera-Hermida, 2020). Most studies have focused on face-to-face university students. Indeed, in approximately 50% of university students in a recent survey, the COVID-19 pandemic led to fewer study hours and a decline in their academic performance (Aucejo et al., 2020). Furthermore, around 10% of the students delayed their graduation, they withdrew from classes, and there was a higher intention to change their studies. Some individuals studied less than usual during this time, although others spent more time studying, depending on their personal circumstances. The amount of time available to study during the COVID-19 restrictions may have depended on several factors. Low income and health problems might affect a student’s available study time (Aucejo et al., 2020), with the pandemic probably exacerbating the socioeconomic disparities in higher education. Indeed, how life-related difficulties influence the time it takes to complete academic activities in an online learning context has recently been assessed (Aristeidou & Cross, 2021). Elsewhere, lockdown restrictions were not seen to deteriorate academic grades relative to those before the pandemic, despite having adverse effects on the individual’s life. Enhanced academic performance of students has been reported during the pandemic, for example, among a sample of Spanish students who performed better during the spread of COVID-19 than those in an earlier cohort (González et al., 2020). In fact, a comparison of academic grades among Spanish university students who completed a face-to-face course before the pandemic and those who completed the same course entirely through distance learning during spring 2020, concurrent with the COVID-19 restrictions, indicated the results achieved were better during emergency online learning (Iglesias-Pradas et al., 2021). However, these improvements may reflect several issues, such as the use of technology when students shift from face-to-face methods (García-Peñalvo et al., 2020) or the increase in the time available to study (Liao et al., 2022).

Time management plays a significant role in successful learning (Aeon et al., 2021), especially in the distance education context (Neroni et al., 2019). The time available for study may be a relevant issue if the importance of time management skills in the online learning environment is taken into account (Hodges et al., 2020). The greater flexibility and autonomy of students in online learning places greater importance on their time management skills (Zhu et al., 2020). There is evidence that the number of hours dedicated to study is related to academic performance (Bernt & Bugbee, 1993), and as the COVID-19 restrictions may have provoked changes in the time available for study, the student’s perception of having more or less time to study may have affected their academic achievement. Nevertheless, the impact of the pandemic on the study time available to distance learners has not been addressed to date.

The relationship of age with stress and academic achievement among university students during the COVID-19 restrictions

In general, younger generations appear to be more vulnerable to perceived stress, as reflected in the development of disorders involving anxiety and depression (Mazza et al., 2020; Nwachukwu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Indeed, these populations have been seen to be more strongly affected by the psychological consequences of the pandemic (Aucejo et al., 2020; Husky et al., 2020; Rogowska et al., 2020), which may in part reflect that they are part of the active workforce, and they might suffer greater economic challenges as a result of business closures (Salari et al., 2020). The uncertainty and forced isolation associated with the COVID-19 outbreak may have had a negative psychological impact on university students during quarantine (Pedrosa et al., 2020), who, as emerging adults, are a vulnerable group three times more likely to develop mental health complaints than the general population (Arnett, 2016; Auerbach et al., 2016). University students are particularly vulnerable to prolonged situations of stress (Xiong et al., 2020), and in this regard, the impact of the pandemic on stress in university students has been assessed considering the age of students. When students between 19 and 27 years old were studied at eight universities in Germany, it was not possible to detect differences in the influence of age on mental health or distress (Gewalt et al., 2022). However, higher mean stress, anxiety, and depression were found during the pandemic among 18–25 years old in Spain (mostly university students), as well as in those who were 26–60 years old, although the average in the three dimensions was lower for those over 60 (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020). This may reflect that younger students cope less effectively with stress due to using fewer active coping strategies than older students, probably because they generally have less life experience and fewer environmental resources (Babicka-Wirkus et al. 2021; Lopes & Nihei, 2021). Despite these studies analyzing stress in face-to-face university students during the pandemic, no study has yet emerged on this in the context of distance online education.

In terms of academic achievement, to our knowledge, the influence of age on achievement has not been studied in the context of the pandemic, although there is moderate evidence that older university students obtain higher grades (Richardson et al., 2012). However, studies have generally focused on students within a limited age range, in particular younger adults studying at face-to-face universities. In the context of online education, fewer studies have analyzed the relationship between student age and academic performance. In a study conducted at a Spanish distance learning university where students are mature individuals (62.6% between 25 and 40 years of age, and 34.5% aged from 41 to 55), the older students are more confident in their learning abilities, which in turn leads to better academic performance (Castillo-Merino & Serradell-Lopéz, 2014). However, in another study also conducted at a Spanish online university with 21- to 70-year-old subjects, younger students obtained better academic achievement (Bravo-Agapito et al., 2021). Indeed, a recent systematic review highlighted that the relationship between the age of students at distance online universities and academic performance is unclear, suggesting that other factors like academic self-efficacy may have greater importance (Chung et al., 2022).

The mediational role of academic self-efficacy

Self-efficacy theory refers to beliefs about one’s capabilities to perform or learn a specific task at designated levels (Bandura, 1997). Self-efficacy can be considered an essential factor related to motivation and the regulation of students learning, with effects on academic performance (Bandura, 1995). Academic self-efficacy is associated with self-regulated learning, and it helps students to accomplish long-term tasks through the use of self-regulation strategies like self-monitoring, self-evaluation, goal setting, and planning (Zimmerman et al., 1992). For decades, evidence supports the idea that self-efficacy can influence the outcomes of achievement-related actions (Zimmerman, 1990). Students with strong self-efficacy have good learning self-regulation skills and the necessary strategies to regulate behaviour at the time of learning (Schunk & Pajares, 2002). These students feel more efficacious about their learning, adopting more adaptive behaviours, they work harder, they persevere in difficult times, and their academic achievements are better (Schunk & Pajares, 2004). Academic self-efficacy stands out as a dynamic factor that evolves with learning, given that students bring different levels of self-efficacy to learning scenarios, and as they engage in a task, performance cues are received and used to assess their progress, and they reinforce their self-efficacy for ongoing learning. This perceived advancement fuels motivation and fosters sustained learning (Schunk, 2001), underlining the crucial role of academic self-efficacy in the learning process.

Self-efficacy is not an inherent trait but, rather, it is a cognitive construct shaped by various information sources (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2016). These sources encompass vicarious experiences, social persuasion, and physiological and emotional indicators, as well as enactive mastery experiences (Usher & Pajares, 2008). Information about self-efficacy derived from the four aforementioned sources does not directly affect self-efficacy, as it undergoes cognitive appraisal (Bandura, 1997). During this appraisal, individuals assess and integrate various personal and situational factors, such as task difficulty or the effort expended (Schunk 2001). The basis for these interpretations resides in the information individuals choose, and the rules they apply to weigh and combine this information. Indeed, the individuals’ interpretations based on their actions and achievements supply the data that shapes their self-efficacy. In higher education, researchers began to examine the potency of these sources by investigating the possible situational and instructional factors in educational contexts that affect a students’ self-efficacy, demonstrating that several factors appeared to influence this phenomenon (van Dinther et al., 2011).

In analyzing its relationship with age, academic self-efficacy can change in different stages of life. Although the precision of academic self-efficacy in children increases with age, it declines as they progress in the educational system, during adolescence and early adulthood (Shunk & DiBenedetto, 2016). The relationship between self-efficacy and academic achievement is reciprocal in adults while unidirectional in children. This can be attributed to the fact that adults, with their advanced cognitive development and extensive educational background, can form distinct and notably accurate evaluations of past performance results or anticipated task complexities, leading to variations in self-efficacy levels (Talsma et al., 2018). Earlier studies showed that academic self-efficacy can buffer perceived stress in university students (Pierceall & Keim, 2007; Zajacova et al., 2005). Indeed, the self‐efficacy underlying self‐regulation had a protective effect against the increase in students’ stress after the outbreak of COVID‐19, where stress was linked to procrastination (Keyserlingk et al., 2022).

Considering the dynamic nature of academic self-efficacy, it was hypothesized that the uncertainty in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, and especially the moment of confinement, could have affected the self-efficacy beliefs associated with university students’ learning (Alemany-Arrebola et al., 2020). The psychological pressure of confinement combined with academic demands was proposed as a possible explanation for this phenomenon, and possible changes in academic self-efficacy due to confinement were measured in a longitudinal study of 414 students on a face-to-face university course (Wolniak & Burman, 2022). However, this study showed how academic self-efficacy was enhanced during confinement, such that the student’s sense of agency was thought to be stimulated amid the overall disruption brought on by the pandemic. Self-efficacy and academic grades were compared in university students in the age range from 18 to 51 (average of 23.5 years old) before and after COVID-19 (Talsma et al., 2021). Moreover, how a students’ perception of COVID-19 predicted academic performance outcomes, both directly and indirectly, was also studied, particularly through the influence on self-efficacy beliefs. As postulated by Bandura’s social cognitive theory (1997), students’ academic performance may be affected by modifications to their academic self-efficacy, which can occur through the influence of environmental factors. Individuals utilize their personal feelings of excitement, uncertainty, worry, stress, and exhaustion as indicators of their own effectiveness (Usher and Pajares, 2008). Feelings of calm can boost self-belief, while negative emotions related to academic tasks can weaken beliefs about one’s ability, lowering performance expectations (Bandura, 1995). Talsma et al. (2021) consider how the emotional states generated during the pandemic could be identified as an influence on self-efficacy beliefs. To test this hypothesis, participants were asked to specify what effect they thought COVID-19-related changes to their university context would have on their ability to perform in their studies. The results of this study showed that students’ beliefs about the impact of COVID-19 on their ability did not predict either their grades or self-efficacy, where self-efficacy was found to be the only significant predictor of students’ grades. However, another measure could have been used to assess the perceptions related to COVID-19, such as the student’s dedication to study during the pandemic (Talsma et al., 2021). It was proposed that this measure, which refers to the time available for study, may influence academic performance. Hence, the reduction in social activities or the unemployment/underemployment associated with the COVID-19 pandemic could have led to more time being available for study, as pointed out previously (Aucejo et al., 2020).

While has been established that self-efficacy plays a crucial role in the academic performance of university students (Schunk & Pajares, 2004), more research is needed to analyze this relationship in online learning environments, and to fully understand the factors that influence such connections. Self-efficacy is especially relevant in the context of online distance education, as students must assume a greater degree of responsibility in planning and organizing their own learning (González-Benito et al., 2021). In this context, self-efficacy has been linked to better academic outcomes and greater adaptation to the distance learning modality (Zimmerman & Kulikowich, 2016). A meta-analysis demonstrated that academic self-efficacy tended to correlate with academic performance in the online learning environment in similar manner to that found in a general learning environment (Yokoyama, 2019). However, differences were also identified, such that specific characteristics of online learning environments may affect this correlation, like the familiarity with online learning devices and the value of tasks in online learning software. In addition, it is important to note that in online education contexts, academic self-efficacy is related to factors like time management (Zimmerman & Kulikowich, 2016). In learning situations characterized by an online teaching methodology, it is of utmost importance that students manage their time adequately, as they must know how to organize and study autonomously (Broadbent, 2017). For example, these students must organize their assignments, taking into account the management of virtual platforms that may require additional time and cause unforeseen events in terms of respecting deadlines. Moreover, if these analyses in the context of distance learning are carried out in difficult times like the COVID-19 pandemic, they could contribute to further defining the benefits of academic self-efficacy in an online teaching/learning scenario that is increasingly common in today’s world.

The current study

In this study, we assume that online learning methodology remained substantially unchanged during the COVID-19 restrictions. However, the pandemic did constitute a new personal and social context for students from online universities, probably changing factors like the time available for study that could in turn have repercussions on stress and academic achievement. In this regard, a student who perceives they have little time for study in a context such as that generated by confinement could feel further pressure regarding their academic work, apart from having the usual tasks and difficulties related to studying in a university context (such as having to submit tasks on time). Hence, here we examined the variable perceived study time for students at an online university and its relationship with both stress and academic achievement.

Factors like age and the relationship between stress and academic achievement have been little explored in online students. In the context of the UNED (National University of Distance Education of Spain), we can analyze a wide age range (18–60 years) of students, and more comprehensively explore to what extent age can predict stress and academic grades during a pandemic. This provided us with a privileged context to analyze how psychological maturity affects the affective-academic variables indicated. Finally, we consider it important to analyze the variable academic self-efficacy in students at an online university during the pandemic. We explored the mediating role of academic self-efficacy as a mechanism that students of various ages would use to confront the new situation, and as a factor that explains the perceived stress and academic achievement. Furthermore, perceiving a change in the availability of time may require an adaptation and adjustment in the planning of a task, where academic self-efficacy plays an important role since it expresses motivational beliefs that can influence the student’s work. Limited research has focused on how the exceptional circumstances of COVID-19 might influence the self-efficacy beliefs of university students, and our study has the added value of analyzing this aspect in the context of distance online education.

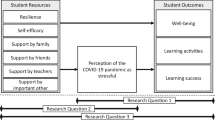

In the current study, employing an ex post facto and cross-sectional design, we aim to undertake a global analysis of all these factors and based on the existing literature, we propose a predictive model (Fig. 1) to examine the direct effects of the variables’ age and perceived study time on both stress and academic achievement, as well as their indirect effects through the mediating academic self-efficacy.

As a result, we formulated the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1: The perceived study time is positively related to both academic self-efficacy and academic achievement (H1a), and negatively associated with stress (H1b).

-

Hypothesis 2: Age is positively related to both academic self-efficacy (H2a) and academic achievement (H2b), and negatively associated with stress (H2c).

-

Hypothesis 3: Academic self-efficacy is negatively associated with stress (H3a) and it is positively related to academic achievement (H3b).

-

Hypothesis 4: Age and perceived study time have an indirect effect on both stress and academic achievement, with academic self-efficacy acting as a mediating variable.

Methods

Participants

The total sample consisted of 1030 undergraduate psychology students at the UNED, of whom 267 (25.9%) were male and 763 (74.1%) were females. The age ranged from 18 to 60 years (M = 35.11, SD = 10.89). In relation to marital status, 541 (52.5%) of the sample was married or with a stable partner, 421 (40.9%) were single, 61 (5.9%) were separated or divorced, and 7 (0.7%) were widowed. In terms of employment, 638 (61.9%) subjects in the sample were employed and 392 (38.1%) unemployed.

Measures

Sociodemographic data was obtained through a brief questionnaire specifically designed for this study: age, gender, marital status, and employment situation.

Perceived study time was measured with an item established ad hoc and evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale. It assessed how the changes brought about by the pandemic were perceived to affect the time available for study. In particular, the participants were asked whether the time spent studying had decreased or increased since the confinement because of the pandemic: 1 = significantly decreased, 2 = somewhat decreased, 3 = neither decreased nor increased, 4 = somewhat increased, and 5 = significantly increased.

Academic self-efficacy was assessed using the School Self-Efficacy Scale (Pastorelli & Picconi, 2001), which was translated and adapted to Spanish, and then back-translated to ensure the accuracy of the translation. Two bilingual experts were involved in obtaining the Spanish version and translating it back into Italian, as well as in correcting any discrepancies between the two versions. After adaptation to a distance learning university context, perceived self-efficacy in performing specific academic tasks and achieving educational goals was measured with ten items, each evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = not at all good to 5 = very good (e.g. ‘carry out research or assigned tasks by independently consulting material that you can find at home, in the library and on the Internet’ or ‘prepare for several exams at the same time’). The total score for this scale ranges from 10 to 50 points. The original scale was shown to have high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranging from 0.83 to 0.86 depending on the subject. In the present study, this coefficient was 0.85.

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS: Cohen et al., 1983; Spanish adaptation by Remor, 2006) was used to assess the variable stress. This scale is a self-report instrument that evaluates the level of perceived stress over the last month, assessing 14 items with a 5-point Likert scale: 0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = very often (e.g. ‘In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly’). The total score ranged from 0 to 56 points, which was obtained by summing the scores for all the items of the scale, and a higher score indicates more perceived stress. However, the PSS is not a diagnostic instrument and thus, there are no cutoffs to classify ‘high’, ‘medium’, or ‘low’ stress (Cohen et al. 1983). The internal consistency of the original scale (measured by Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.81 and here this was 0.90.

Academic achievement was assessed through the grade point average (GPA) obtained by the participants in the examined subjects they took in the second semester of the course. This information was collected from the administration of the Faculty of Psychology, with the scores for each subject ranging from 0 to 10 points. The subjects examined were all worth 6 ECTS (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System), where one ECTS is equivalent to 25 h of study in Spain.

Procedure

Psychology students at UNED were recruited following a structured protocol, which involved inviting them to participate in the study through direct messages and the forums associated with the Psychology courses themselves. Interested individuals who wished to take part in the study contacted the research team and after the nature and aims of the research was explained to them, each participant was asked to provide their consent to participate as a prior requisite for their enrolment onto the study.

The data was collected in May 2020 using the Qualtrics tool (http://www.qualtrics.com/), through which the participants accessed the questionnaires and scales used. The participants took approximately 20–25 min to complete the questionnaires and all the students were surveyed in their second semester. The data was collected before the second-semester exams, which took place in June 2020. Data regarding academic achievement was obtained from the grades achieved in the same month of June. It is important to note that the lockdown in Spain began on March 12th and that the first-semester exams at the UNED ended in mid-February, so students experienced the effects of lockdown for almost the entire second-semester. This allowed them to focus their perceptions regarding their dedication to their studies only on this particularly complex period. A total of 1081 students enrolled onto the study but after excluding the participants who did not complete all the questionnaires, a final sample of 1030 participants was obtained. Participation was voluntary and but there was an incentive as the participants received one ECTS credit for completing the survey. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at the UNED.

Data analysis

A preliminary analysis was carried out to test the assumptions of multivariate normality and to identify any outliers in the sample before examining the structural model. Multivariate normality was confirmed using Mardia’s (1970) multivariate kurtosis coefficient, which was − 2.15. A critical kurtosis ratio < 5.0 demonstrates multivariate normality (Bentler, 2006). No multivariate outliers were found after calculating the Mahalanobis’ distance.

Descriptive statistics were calculated, including means and standard deviations, and Pearson’s correlations were examined to explore the relationships between the variables studied. This analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 and a path analysis using maximum likelihood was then performed using AMOS 25.0 software (Arbuckle, 2006).

Several indices and goodness-of-fit criteria were used to evaluate the overall fit of the model, as recommended (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2011): a normed chi-square (χ2/df < 3 acceptable and < 2 excellent); a comparative fit index (CFI > 0.90 acceptable and > 0.95 excellent); a normed fit index (NFI > 0.90 acceptable and > 0.95 excellent); standard root mean square residual (SRMR < 0.08 acceptable and < 0.05 good); and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08 acceptable and < 0.06 good). Finally, we evaluated the mediating effects using a bootstrapping method as recommended (Cheung & Lau, 2008), with 5000 bootstrap samples and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI). The mediation effect is considered statistically significant at the level of α = 0.05 if the CI does not include 0, showing an indirect effect (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

Results

Descriptive analysis and correlations

The descriptive statistics, including the means, standard deviations, and the Pearson’s correlation coefficients, was calculated for all the study variables (Table 1).

The mean score for academic self-efficacy was statistically significantly higher than the midpoint of the scale (M = 37.68, midpoint = 30, t(1029) = 41.1, p < 0.001), and the same was true for academic achievement (M = 6.7, midpoint = 5, t(1029) = 29.22, p < 0.001). These results suggest that the participants generally had relatively high levels of both academic self-efficacy and academic achievement during the lockdown period. In contrast, the mean scores for perceived study time were statistically significantly below the midpoint of the scale (M = 2.15, midpoint = 2.5, t(1029) = − 9.49, p < 0.001), and the same was true for stress (M = 25.80, midpoint = 28, t(1029) = − 7.71, p < 0.001). These results suggest that, on average, the participants believed they spent less time studying and experienced lower levels of stress during the lockdown.

All the variables were significantly correlated in the directions predicted. Age and perceived study time were negatively correlated with stress, yet positively associated with academic self-efficacy and academic achievement. In turn, academic self-efficacy was negatively related to stress, while there were no significant associations between academic achievement and either age or stress.

Model testing and mediation analysis

The path analysis revealed that the model proposed showed a good fit to the data: χ2 /df = 0.28, CFI = 1.000, NFI = 0.999, SRMR = 0.0043, and RMSEA = 0.000. The path coefficients represented in Fig. 2 were all statistically significant.

Specifically, age predicted both academic self-efficacy (β = 0.11, p = 0.000) and stress (β = − 0.27, p = 0.000), yet age was not a predictor of academic achievement. In turn, perceived study time was a predictor of the three variables academic self-efficacy (β = 0.20, p = 0.000), stress (β = − 0.19, p = 0.000), and academic achievement (β = 0.10, p < 0.01). Finally, academic self-efficacy predicts stress (β = − 0.33, p = 0.000) and academic achievement (β = 0.16, p = 0.000).

We examined the mediating role of academic self-efficacy to the extent that it could account for the relationship between the predictors (age and perceived study time) and the criteria stress or academic achievement. The findings indicated that age was not related to academic achievement as it did not satisfy one of the four conditions necessary to find a mediation effect (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Hence, only three path mediations were examined (see Table 2).

According to the results, age had a direct effect on stress, as well as an indirect effect through academic self-efficacy. In turn, perceived study time had a direct effect on both outcome variables (stress and academic achievement) and an indirect effect through academic self-efficacy. We evaluated if the direct β value without a mediator diminishes when the mediator is included (Table 2), a condition that is satisfied in the three paths examined (partial mediation). Finally, the bootstrapping method shows that the mediation effect is considered statistically significant at the level of α = 0.05 because the CI does not include zero.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to test the model proposed in the context of a distance university during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research adopted a multidimensional approach, examining by analysis path of the direct relationships between age and perceived study time with both stress and academic achievement, as well as the indirect effects through academic self-efficacy and their mediating role in the model. The fit of the empirical model allowed us to confirm our proposed predictive hypotheses. We found only one exception: age was not a predictor of academic achievement, and therefore there was no mediating effect of academic self-efficacy between these two variables.

Very few studies have examined the variables studied here in the context of an online university and we found none did so from a multidimensional perspective at the time of the pandemic. Students at a national distance university like the UNED are characterized by their wide age range and distinct personal situations (Johnson, 2015), and they were using online methodology even prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. Online education implies an organizational infrastructure aligned with the goals of remote teaching and learning, and it is not a methodology applied temporarily (Fuchs, 2022).

The pandemic outbreak may have negatively affected university students’ mental health, exposing them to stress (Liyanage et al., 2022; Tasso et al., 2021). Here, a negative relationship between age and stress (H2c) was defined, although during the pandemic outbreak older students report lower levels of stress than younger students. This is consistent with findings in the general population (Justo-Alonso et al., 2020; Rodriguez-Rey et el., 2020) and in a traditional university setting that was forced to adopt a remote learning model during the pandemic, both environments in which students between the ages of 18 and 24 typically suffer more distress than older students (Browning et al., 2021; Prowse et al., 2021).

The findings of this study shed light on the stress levels among university students attending an online distance university. In our study, participants experienced low stress levels. However, it’s important to note that 75% of the participants are over 25 years old. These results align with the Spanish research by Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al. (2020), where participants aged 18 to 25, predominantly university students, demonstrated higher stress levels than individuals aged 26 to 60. The isolation provoked by the COVID-19 lockdown had a negative impact on stress in younger students even though their study methodology did not undergo significant changes, unlike those at other universities. There may be multiple reasons underlying these results. In a study into the psychological impacts of COVID-19 among 2534 university students in the USA, younger students appeared to be more concerned about their future education and college expenses than older students (Browning et al., 2021). Moreover, as the pandemic dominated the news, younger people may be exposed to more messages of the increased risk that had a negative impact on mental health, given that young people use social media more frequently than older people. This finding may also reflect the need of younger students for more life experience, resources, and strategies to cope effectively with stress (Babicka-Wirkus et al., 2021).

Alternatively, the personal and social situations experienced during the pandemic may also have affected the student’s perception of the time available for study. Our research examines this issue by asking students whether the time they had available for study increased, stayed the same, or decreased during the pandemic. The participants reported perceiving less time to dedicate to their studies, probably because during lockdown, students in an online context may have life-related difficulties that influence the time it takes to complete academic activities (Aristeidou & Cross, 2021). We found that the perceived study time had a significant relationship with stress (H1b), so students who perceived that their study time was reduced during the pandemic had higher stress levels. The situation may exceed the student’s resources to cope with this in terms of completing academic tasks, studying course content, and acquiring sufficient knowledge to pass exams. Conversely, those who perceived their study time had increased had lower levels of stress, probably because they perceived they had the time to manage and control the situation. Therefore, a reduction in the perceived study time available may be a significant stressor. Indeed, university students who consider time as a scarce resource are more likely to perceive stress. For example, a meta-analysis into time management and stress associated with academic failure in medical students showed that students who must cope with an intensive training curriculum with activities to be performed in limited time can have significant problems using their time efficiently. Strong time-related demands, such as higher workloads, time pressure, and regulation of self-study, may be a source of perceived stress, especially for less experienced students (Ahmady et al., 2021).

In addition to these direct effects, we proposed in the model that age and perceived study time indirectly affect stress through academic self-efficacy (H4). Self-efficacy is the students’ confidence in selecting and applying the self-regulated strategies required to achieve academic success (Zimmerman & Martinez-Pons, 1990). The theory of self-regulated learning has shown to be a good framework to explain the performance and success of students at online universities (Broadbent & Poon, 2015; Lynch & Dembo, 2004). Academic self-regulation was defined as the extent to which learners are meta-cognitively, motivationally, and behaviourally active in achieving their learning goals (Zimmerman, 1989). In the context of a distance university, students are more autonomous than in a traditional university (Broadbent, 2017) and they feel more responsible for their academic performance. In our study, participants have high academic self-efficacy, which could be explained by considering that they are all adults with a sense of agency stimulated by the situation generated by the pandemic (Talsma et al., 2018; Wolniak & Burman, 2022). One of the important findings of this study was the mediating role that academic self-efficacy plays in the model proposed (H4). Age is positively related to academic self-efficacy (H2a), such that older students have more academic self-efficacy. In online learning, autoregulatory skills like independent time management and self-monitoring are still developing in the age range of 18 to 25 years (Murray et al., 2015), and these young adults are still dependent on co-regulation by parents or teachers. Older students have more experience than younger ones, and better defined academic strengths and weaknesses, establishing a better basis for making accurate self-efficacy appraisals (Multon et al., 1991). Student age is also an important variable, with older students more likely to use discussion boards, and they tend to achieve better grades in online courses (Alstete & Beutell, 2004). This suggests that younger students may need more time to be ready for the self-directed and self-disciplined nature of online courses, and they may need more support from instructors regarding the online format. Our study also found that academic self-efficacy was negatively related to stress (H3a), an outcome consistent with the finding that students with low levels of self-efficacy suffer more stress (Navarro-Mateu et al., 2020). Self-efficacy and self-regulation can have a protective effect against the increase in stress of students during the lockdown in the spring of 2020 (Keyserlingk et al. 2022). One explanation is that students confident in their ability to learn perceived the situation created by the pandemic as less threatening and therefore they experienced less stress.

Regarding academic achievement, while a positive association with self-efficacy was found (H3b), there was no significant association with age (H2b), indicating that academic self-efficacy does not mediate between age and academic achievement (H4). Age is independent of performance in terms of the academic grades obtained by these students during the pandemic, which is consistent with other studies that failed to find an association between age and academic performance in students at distance universities. In a study performed on distance university students of different age ranges, older students study for longer than young students and they better use learning strategies, although age did not affect academic performance (Neroni et al., 2019). These results were also confirmed in studies that considered traditional students. An extensive review of academic achievement and correlates showed older students obtained higher grades (Richardson et al., 2012), yet these effects were small except for the large correlation observed between performance and self-efficacy.

The hypothesis about the mediating role of academic self-efficacy between perceived study time and academic achievement was confirmed (H4). Our results show that perceived study time is directly and positively related to academic achievement. In this sense, students who perceive they have less time to study also perform worse academically. These results highlight the importance of considering students’ perceptions of time and their self-beliefs in relation to their academic performance. In a distance theory framework, autonomy was proposed to be based on distance learners’ ability to control their learning (Moore, 1993). In this sense, previous studies suggested that effectively managing learning time is relevant to distance learner success. Time management and effort were the most important and positive predictors of academic performance in students from a distance university (Broadbent, 2017; Neroni et al., 2019). This also seems to be the case in times of the pandemic, indicating that the perception of having less or more time to study directly affects academic performance in a negative or positive manner, respectively. Moreover, our study confirms the existence of an indirect effect, revealing that students who perceive having less study time also exhibit lower levels of academic self-efficacy. This suggests that having less time to study negatively affects academic self-efficacy or belief about their ability to complete academic tasks. In turn, self-perception of ability and competence to perform a specific task is significantly related to academic achievement, as seen elsewhere (Ahmady et al. 2021).

Limitations

Our research has some limitations that must be borne in mind. The study adopted a cross-sectional design with limited causal relationships between the study variables. Hence, future longitudinal research should be conducted to establish robust casual relationships. Furthermore, given the complexity of the issue, other educational (e.g. learning strategies related to self-regulation or different learning technology) or sociodemographic variables (e.g. family income) could be explored in the future to determine their effect on the proposed model of stress and academic achievement in an online learning university. High levels of stress among students are worrying as it affects their mental well-being; hence, the mediating role of academic self-efficacy in difficult times like the pandemic is an important fact that needs to be explored in later studies. On the other hand, we need to know more about the factors that influence self-efficacy in online university learning, and whether these factors might influence the relationship between self-efficacy and academic performance.

Practical implications

Despite these limitations, the current study has practical implications for educational and clinical interventions used with online learning university students over different age ranges. In a difficult period, like the pandemic lockdown, perceiving less study time may be a negative factor for students, with a negative impact on both stress and academic achievement. We suggest that students who perceive they have less time need to develop more effective time management skills, such as setting practical goals, prioritizing tasks, and taking regular breaks to recharge. Therefore, educators may take these needs into account to help students succeed academically. We believe that teaching practical strategies in the context of online learning may be helpful and it is a possibility that should be carefully explored. Indeed, further research could explore programmes aimed at achieving this. Furthermore, it is worth noting that high academic self-efficacy is a valuable attribute for students, providing a protective factor against stress and yielding positive effects on academic achievement, even in challenging circumstances like the COVID-19 lockdown. In the light of this evidence, it would be beneficial to develop targeted interventions that specifically address the needs of online learning students with weak self-efficacy.

In conclusion, it is essential to recognize the importance of tailoring interventions to meet the specific needs and circumstances of individual students in online learning. By incorporating evidence-based practices that promote self-efficacy, educational institutions can better support students to build resilience, reduce stress, and achieve academic success in the face of challenging situations like the COVID-19 lockdown.

Data availability

The data from the current study is available upon request to the corresponding author, as deemed reasonable.

References

Aeon, B., Faber, A., & Panaccio, A. (2021). Does time management work? A Meta-Analysis. Plos ONE, 16(1), e0245066. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245066

Aguilera-Hermida, A. (2020). College students use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 1, 100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100011

Ahmady, S., Khajeali, N., Kalantarion, M., Sharifi, F., & Yaseri, M. (2021). Relation between stress, time management, and academic achievement in preclinical medical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 10, 32. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_600_20

Alemany-Arrebola, I., Rojas-Ruiz, G., Granda-Vera, J., & Mingorance-Estrada, Á. C. (2020). Influence of COVID-19 on the Perception of Academic Self-Efficacy, State Anxiety, and Trait Anxiety in College Students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.570017

Ali, W. (2020). Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: A necessity in light of COVID-19 Pandemic. Higher Education, 10, 16–25. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v10n3p16

Alstete, J., & Beutell, N. (2004). Performance indicators in online distance learning courses: A study of management education. Journal of Quality Assurance in Education, 12, 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880410517397

Arbuckle, J. L. (2006). AMOS (Version 7.0) [Computer Program]. Chicago: SPSS.

Aristeidou, M., & Cross, S. (2021). Disrupted distance learning: The impact of Covid-19 on study habits of distance learning university students. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 36(3), 263–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2021.1973400

Arnett, J. J. (2016). College students as emerging adults: The developmental implications of the college context. Emerging Adulthood, 4, 219–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696815587422

Aucejo, E. M., French, J., Ugalde Araya, M. P., & Zafar, B. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. Journal of Public Economics, 191, 104271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104271

Auerbach, R. P., Alonso, J., Axinn, W. G., Cuijpers, P., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., et al. (2016). Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine, 46, 2955–2970. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001665

Babicka-Wirkus, A., Wirkus, L., Stasiak, K., & Kozłowski, P. (2021). University students’ strategies of coping with stress during the coronavirus pandemic: Data from Poland. PLoS ONE, 16(7), e0255041. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255041

Bakioğlu, F., Korkmaz, O., & Ercan, H. (2020). Fear of COVID-19 and positivity: Mediating role of intolerance of uncertainty, depression, anxiety, and stress. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19, 2369–2382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00331-y

Bandura, A. (Ed.). (1995). Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511527692

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bentler, P. M. (2006). EQS 6 Structural equations program manual. Multivariate Software, Inc.

Bernt, F. M., & Bugbee, A. C. (1993). Study practices and attitudes related to academic success in a distance learning programme. Distance Education, 14(1), 97–112.

Birbeck, D., McKellar, L., & Kenyon, K. (2021). Moving beyond the first year: An exploration of staff and student experience. Student Success, 12(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.1802

Bravo-Agapito, J., Romero, S. J., & Pamplona, S. (2021). Early prediction of undergraduate Student’s academic performance in completely online learning: A five-year study. Computers in Human Behavior, 115, 106595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106595

Broadbent, J. (2017). Comparing online and blended learner’s self-regulated learning strategies and academic performance. The Internet and Higher Education, 33, 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.01.004

Broadbent, J., & Poon, W. L. (2015). Self-Regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. The Internet and Higher Education, 27, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.04.007

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395, 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Browning, M. H. E. M., Larson, L. R., Sharaievska, I., Rigolon, A., McAnirlin, O., Mullenbach, L., et al. (2021). Psychological impacts from COVID-19 among university students: Risk factors across seven states in the United States. PLoS ONE, 16(1), e0245327. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245327

Castillo-Merino, D., & Serradell-Lopéz, E. (2014). An analysis of the determinants of students’ performance in e-learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 476–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.020

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Colleges, universities, and higher learning. Retrieved August 5, 2021 from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/colleges-universities/index.html

Cheung, G. W., & Lau, R. S. (2008). Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 11, 296–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1094428107300343

Chu, I. Y. H., Alam, P., Larson, H. J., & Lin, L. (2020). Social consequences of mass quarantine during epidemics: A systematic review with implications for the COVID-19 response. Journal of Travel Medicine, 27(7), 192. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa192

Chung, J., McKenzie, S., Schweinsberg, A., & Mundy, M. E. (2022). Correlates of academic performance in online higher education: A systematic review. Frontiers in Education, 7, 820567. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.820567

Clabaugh, A., Duque, J. F., & Fields, L. J. (2021). Academic stress and emotional well-being in United States college students following onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 628787. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.628787

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 24, 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

Gobierno de España. (2020). Available online at: https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/ (accessed March 22, 2020).

Gobierno de España. (2023). Crisis sanitaria COVID-19: Normativa e información útil. Retrieved December 2, 2023 from https://administracion.gob.es/pag_Home/atencionCiudadana/Crisis-sanitaria-COVID-19.html

Faura-Martínez, U., Lafuente-Lechuga, M., & Cifuentes-Faura, J. (2022). Sustainability of the Spanish university system during the pandemic caused by COVID-19. Educational Review, 74(3), 645–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1978399

Fuchs, K. (2022). The difference between emergency remote teaching and e-learning. Frontiers in Education, 7, 921332. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.921332

García-Peñalvo, F. J., Corell, A., Abella-García, V., & Grande, M. (2020). La evaluación online en la educación superior en tiempos de la COVID-19. Education in the Knowledge Society (EKS), 21, 26. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.23086

Gewalt, S. C., Berger, S., Krisam, R., & Breuer, M. (2022). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ physical health, mental health and learning, a cross-sectional study including 917 students from eight universities in Germany. PLoS ONE, 17(8), e0273928. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0273928

González, T., de la Rubia, M. A., Hincz, K. P., Comas-Lopez, M., Subirats, L., Fort, S., et al. (2020). Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PLoS ONE, 15, e0239490. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239490

González-Benito, A., López-Martín, E., Expósito-Casas, E., & Moreno-González, E. (2021). Motivación académica y autoeficacia percibida y su relación con el rendimiento académico en los estudiantes universitarios de la enseñanza a distancia. RELIEVE - Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 27(2). https://doi.org/10.30827/relieve.v27i2.21909

González-Sanguino, C., Ausín, B., Castellanos, M. Á., Saiz, J., López-Gómez, A., Ugidos, C., & Muñoz, M. (2020). Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 172–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T. & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review. Retrieved February, 9, 2023 from https://bit.ly/3b0Nzx7

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Husky, M. M., Kovess-Masfety, V., & Swendsen, J. D. (2020). Stress and anxiety among university students in France during Covid-19 mandatory confinement. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 152191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152191

Iglesias-Pradas, S., Hernández-García, Á., Chaparro-Peláez, J., & Prieto, J. L. (2021). Emergency remote teaching and students’ academic performance in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Computers in Human Behavior, 119, 106713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106713

Johnson, G. M. (2015). On-campus and fully-online university students: Comparing demographics, digital technology use and learning characteristics. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.53761/1.12.1.4

Justo-Alonso, A., García-Dantas, A., González-Vázquez, A. I., Sánchez-Martín, M., & Del Río-Casanova, L. (2020). How did different generations cope with the COVID-19 pandemic? Early stages of the pandemic in Spain. Psicothema, 32(4), 490–500. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2020.168

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Liao, W., Abukhalaf, R., & Powell, J. W. (2022). COVID-19’s effect on study hours for business students transitioning to online learning. Journal of Education for Business. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2022.2103488

Liyanage, S., Saqib, K., Khan, A. F., Thobani, T. R., Tang, W.-C., Chiarot, C. B., AlShurman, B. A., & Butt, Z. A. (2022). Prevalence of anxiety in university students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010062

Lopes, A. R., & Nihei, O. K. (2021). Depression, anxiety and stress symptoms in Brazilian university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Predictors and association with life satisfaction, psychological well-being and coping strategies. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0258493. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258493

Lynch, R., & Dembo, M. (2004). The relationship between self-regulation and online learning in a blended learning context. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v5i2.189

Mardia, K. V. (1970). Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika, 57, 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/57.3.519

Mazza, C., Ricci, E., Biondi, S., Colasanti, M., Ferracuti, S., Napoli, C., & Roma, P. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093165

Moore, M. (1993). Theory of transactional distance. In D. Keegan (Ed.), Theoretical principles of distance education (pp. 22–29). Routledge.

Multon, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991). Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic outcomes: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.38.1.30

Murray, D. W., Rosanbalm, K., Christopoulos, C., & Hamoudi, A. (2015). Self-regulation and toxic stress: Foundations for understanding self-regulation from an applied developmental perspective. Retrieved November 5, 2022 from https://hdl.handle.net/10161/10283

Navarro-Mateu, D., Alonso-Larza, L., Gómez-Domínguez, M. T., Prado-Gascó, V., & Valero-Moreno, S. (2020). I’m not good for anything and that’s why I’m stressed: Analysis of the effect of self-efficacy and emotional intelligence on student stress using SEM and QCA. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 295. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00295

Neroni, J., Meijs, C., Gijselaers, H. J. M., Kirschner, P. A., & de Groot, R. H. M. (2019). Learning strategies and academic performance in distance education. Learning and Individual Differences, 73, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.04.007

Nwachukwu, I., Nkire, N., Shalaby, R., Hrabok, M., Vuong, W., Gusnowski, A., Surood, S., Urichuk, L., Greenshaw, A. J., & Agyapong, V. I. O. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: Age-related differences in measures of stress, anxiety and depression in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176366

Odriozola-González, P., Planchuelo-Gómez, Á., Irurtia, M. J., & de Luis-García, R. (2022). Psychological symptoms of the outbreak of the COVID-19 confinement in Spain. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(4), 825–835. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105320967086

Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Dosil-Santamaria, M., Picaza-Gorrochategui, M., & Idoiaga-Mondragon, N. (2020). Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. Cadernos De Saude Publica, 36(4), e00054020. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00054020

Pastorelli, C. & Picconi, L. (2001). Autoefficacia scolastica, sociale e regolatoria. In G. V. Caprara (Ed,). La valutazione dell’autoefficacia. Costrutti e strumenti (pp. 87–104). Erickson.

Pedrosa, A. L., Bitencourt, L., Fróes, A., Cazumbá, M., Campos, R., de Brito, S., Simões, E., & Silva, A. C. (2020). Emotional, behavioral, and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 566212. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566212

Pierceall, E. A., & Keim, M. C. (2007). Stress and coping strategies among community college students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 31(9), 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920600866579

Pokhrel, S., & Chhetri, R. (2021). A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher Education for the Future, 8(1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347631120983481

Prowse, R., Sherratt, F., Abizaid, A., Gabrys, R. L., Hellemans, K., Patterson, Z. R., & McQuaid, R. J. (2021). Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining gender differences in stress and mental health among university students. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 650759. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.650759

Remor, E. (2006). Psychometric properties of a European Spanish version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 9(1), 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1138741600006004

Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026838

Rodríguez-Rey, R., Garrido-Hernansaiz, H., & Collado, S. (2020). Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic among the general population in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1540. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01540

Rogowska, A. M., Kuśnierz, C., & Bokszczanin, A. (2020). Examining anxiety, life satisfaction, general health, stress and coping styles during COVID-19 pandemic in Polish sample of university students. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 797–811. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S266511

Ruiz-Robledillo, N., Vela-Bermejo, J., Clement-Carbonell, V., Ferrer-Cascales, R., Alcocer-Bruno, C., & Albaladejo-Blázquez, N. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on academic stress and perceived classroom climate in Spanish university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4398. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074398

Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., ... & Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

Sandín, B., Espinosa, V., Valiente, R. M., García-Escalera, J., Schmitt, J. C., Arnáez, S., & Chorot, P. (2021). Effects of coronavirus fears on anxiety and depressive disorder symptoms in clinical and subclinical adolescents: The role of negative affect, intolerance of uncertainty, and emotion regulation strategies. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.716528

Schunk, D. H. (2001). Self-efficacy: Educational aspects. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (pp. 13820–13822). https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/02402-5

Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2002). The development of academic self-efficacy. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 15–31). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012750053-9/50003-6

Schunk, D. H., & DiBenedetto, M. K. (2016). Self-Efficacy theory in education. Handbook of Motivation at School. Routledge. Accessed on: 12 Jan 2023 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315773384.ch3

Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2004). Self-efficacy in education revisited: Empirical and applied evidence. In D. M. McInerney & S. V. Etten (Eds.), Big theories revisited (pp. 115–138). Information Age.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

Talsma, K., Robertson, K., Thomas, C., & Norris, K. (2021). COVID-19 beliefs, self-efficacy and academic performance in first-year university students: Cohort comparison and mediation analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 643408. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643408

Talsma, K., Schüz, B., Schwarzer, R., & Norris, K. (2018). I believe, therefore I achieve (and vice versa): A meta-analytic cross-lagged panel analysis of self-efficacy and academic performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 61, 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.11.015

Tasso, A. F., Hisli Sahin, N., & San Roman, G. J. (2021). COVID-19 disruption on college students: Academic and socioemotional implications. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000996

Usher, E. L., & Pajares, F. (2008). Sources of self-efficacy in school: Critical review of the literature and future directions. Review of Educational Research, 78, 751–796. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308321456

van Dinther, M., Dochy, F., & Segers, M. (2011). Factors affecting students’ self-efficacy in higher education. Educational Research Review, 6(2), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.10.003

von Keyserlingk, L., Yamaguchi-Pedroza, K., Arum, R., & Eccles, J. S. (2022). Stress of university students before and after campus closure in response to COVID-19. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22561

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729

Wolniak, G. C., & Burman, S. C. (2022). COVID-19 disruptions: Evaluating the early impacts of campus closure on academic self-efficacy and motivation. Journal of College Student Development, 63(4), 455–460. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2022.0038

Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., et al. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affect Disorders, 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

Yokoyama, S. (2019). Academic self-efficacy and academic performance in online learning: A mini review. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2794. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02794

Zajacova, A., Lynch, S. M., & Espenshade, T. J. (2005). Self-efficacy, stress, and academic success in college. Research in Higher Education, 46(6), 677–706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-004-4139-z

Zhu, Y., Zhang, J. H., Au, W., & Yates, G. (2020). University students’ online learning attitudes and continuous intention to undertake online courses: A self-regulated learning perspective. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(3), 1485–1519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09753-w

Zimmerman, B. J. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(3), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.81.3.329

Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview. Educational Psychologist, 25(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2501_2

Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 29(3), 663–676. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312029003663

Zimmerman, B. J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1990). Student differences in self-regulated learning: Relating grade, sex, and giftedness to self-efficacy and strategy use. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.51

Zimmerman, W. A., & Kulikowich, J. M. (2016). Online learning self-efficacy in students with and without online learning experience. American Journal of Distance Education, 30(3), 180–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2016.1193801

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors of the manuscript participated in the different phases and tasks of manuscript preparation. That is, they contributed to the conception and design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and revision of the article, and they approved the final version submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Distance Education University (UNED). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.S

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Current themes of research:

Emilia Cabras. Academic achievement; teaching–learning processes in university students with online teaching; self-efficacy. Faculty of Education, Universidad Alfonso X El Sabio, Madrid, Spain.

Pilar Pozo. Autism spectrum disorders; family adaptation; self-efficacy; coping strategies; family quality of life. Department of Methodology of the Behavioral Sciences, Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), C/ Juan del Rosal, 10, 28040, Madrid, Spain. Email: ppozo@psi.uned.es.

Juan C, Suárez-Falcón. Psychological and educational assessment; psychometric properties of scales; acceptance and commitment therapy. Department of Methodology of the Behavioral Sciences, Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), C/ Juan del Rosal, 10, 28,040, Madrid, Spain.

Mariagiovanna Caprara. Personality, individual differences, subjective well-being, life course perspective. Department of Personality Psychology, Evaluation and Psychological Treatment, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Madrid, Spain.

Antonio Contreras. Child development: theory of mind; self-compassion; teaching–learning processes in university students with online teaching. Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Madrid, Spain.

Most relevant publications:

Caprara, M. G., Di Giunta, L., Bermúdez, J., Caprara, G. V. (2020). How self-efficacy beliefs in dealing with negative emotions are associated to negative affect and to life satisfaction across gender and age. PLoS ONE 15(11): e0242326. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242326.

Caprara, M. G., Zuffianò, A., Contreras, A., Suárez-Falcón. J. C., Pozo, P., Cabras, E., & Gómez-Veiga, I. (2023). The protective role of positivity and emotional self-efficacy beliefs in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05159-y.

Contreras, A., & García-Madruga, J. A. (2023). The relationship between theory of mind and peer acceptance in preschool children: A test of the counterfactual hypothesis in the social domain. Early Child Development and Care, 193(5), 617-630. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2022.2130908.

García-Madruga, J. A., Elosúa, M. R., Gil, L., Gómez-Veiga, I., Vila, J. O., Orjales I., Contreras, A., Rodríguez, R., Melero, M. A. y Duque, G. (2013). Reading Comprehension and Working Memory's Executive Processes: An Intervention Study in Primary School Children. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(2), 155-174.

Contreras, A., Suárez-Falcón, J. C., Caprara, M. G., Pozo, P., Gómez-Veiga, I., & Cabras, E. (2023). Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the Complex Postformal Thought Questionnaire: Developmental Pattern and Significance and its Relationship with Cognitive and Personality Measures. Collabra: Psychology, 9(1), 67993. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.67993.

García-Herranz, S., Díaz-Mardomingo, M., Suárez-Falcón, J. C., Rodríguez-Fernández, R., Peraita, H., & Venero, C. (2022). Normative data for the Spanish version of the California Verbal Learning Test (TAVEC) from older adults. Psychological Assessment, 34(1), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001070.

García-López, C., Sarriá, E. & Pozo, P. (2016). Parental Self-Efficacy and Positive Contributions Regarding Autism Spectrum Condition: An Actor–Partner Interdependence Model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 2385–2398 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2771-z.

Von Humboldt, S., Mendoza-Ruvalcaba, N., Arias-Merino, E., Costa, A., Cabras, E., Low, G., & Leal, I. (2022). The meaning in life and smart technology of older adults during the Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-cultural qualitative study. European Psychiatry, 65(S1), S500-S501. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.1272.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cabras, E., Pozo, P., Suárez-Falcón, J.C. et al. Stress and academic achievement among distance university students in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic: age, perceived study time, and the mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Eur J Psychol Educ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-024-00871-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-024-00871-0