Abstract

Family involvement has been identified as a mechanism that explains the differences in academic performance and well-being between students from different socioeconomic backgrounds. The implications of family involvement in students' non-academic outcomes have often been overshadowed by a focus on the academic domain. This study focuses on one type of non-academic attributes which is currently most critical to navigate in school and beyond: social-emotional development. In addition to that, the potential mediating role of school engagement in the association between family involvement and students' social-emotional development remains to be explored. This study aimed to investigate whether family involvement was associated with students' school engagement and social-emotional development and to clarify the underlying mechanism in the relationship. The sample consisted of 170 students from 8 to 17 years old and their parents who live in economically vulnerable situations and experience social exclusion. The analyses were performed using Jamovi statistical software and a GLM Mediation Model module. To address the research objectives, a series of mediation analysis were performed to fit the hypothesized relations among the study variables. The mediational analysis suggested that home-based family involvement could not predict students' social-emotional development, and that the effect of home-based family involvement on students' social-emotional development was fully mediated by school engagement, a variable not included in previous research. The results suggest that families who are actively engaged in their child's education at home positively influence students' level of participation in school, which, in turn, promotes the development of students' social-emotional competences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With numerous studies showing that parental socioeconomic status is passed down to children, there is no doubt of the potential disadvantages faced by students from low-income households (Broer et al., 2019). Data show that children from economically disadvantaged households face additional challenges to achieving comparable educational outcomes to their counterparts from more privileged backgrounds, including higher dropout rates (Winding & Andersen, 2015; Wood et al., 2017) or lower educational performance (Chmielewski, 2019; Lawson and Farah, 2017; Reardon, 2018). In addition to that, parental socioeconomic status exerts a profound influence on students' well-being outcomes such as physical, psychological, and socio-emotional (Jury et al., 2017; OECD, 2020). The so-called intergenerational transmission of disadvantage or intergenerational mobility results then in a reduction of opportunities enjoyed by individuals, perpetuating inequality and limiting opportunities for upward mobility (Ayllón et al., 2022).

The latest findings from PISA assessments by the OECD (2023) paint a concerning picture of educational inequality. On average across OECD countries, students from socioeconomically advantaged backgrounds scored 93 points higher in mathematics than their disadvantaged peers. This performance gap related to socioeconomic status exceeded 93 score points in 22 countries, while in 13 countries, it was 50 points or less. In reading and science, disadvantaged students faced over five times higher odds of low performance compared to their advantaged peers, on average across OECD countries. According to these results, by the age of 15, students' performance in mathematics, reading, and science is significantly influenced by their socioeconomic status (OECD, 2023). These results highlight the influence of socioeconomic status on academic achievement, with implications extending to students' aspirations for tertiary education and future career opportunities, as evidenced by research on the ‘at risk of poverty or social exclusion’ (AROPE) rate by Llano Ortiz and colleagues. (2020). This study reported that 25% of the socioeconomically disadvantaged pupils, who wish to access a highly qualified job, do not believe they can complete tertiary education. Numbers drop to 9% for students who are not at risk of poverty and social exclusion. Despite these disparities, the potential disadvantages faced by students from low-income households in terms of social-emotional development and personality traits have not been paid much attention unless individuals accounted for deficiencies or problematic behaviors in this area (Lechner et al., 2021; Poortvliet, 2021; Spengler et al., 2015).

Family involvement has been identified as a mechanism that explains the abovementioned differences in achievement and overall well-being between pupils from different social backgrounds. The family system is defined as the primary socialization setting and parenting practices are viewed as key drivers for children’s educational success (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Therefore, the protective potential of family involvement is highlighted, which acquires special importance for low-income, disadvantaged student populations (Bulotsky-Shearer et al., 2016). Family involvement is also proved to be a malleable construct, responsive to variations in the environment and a critical target for school interventions (Benner et al., 2016; Castro et al., 2015; Jeynes, 2007).

Family involvement

The bioecological model by Bronfenbrenner and Morris (2006) constitutes a framework for conceptualizing family involvement. This model explains the existence of proximal microsystem contexts where the children reside and actively participate on a daily basis (e.g., school and family). Interactions between those proximal contexts occur at a mesosystem level and contribute to children’s cognitive and social-emotional development. Mesosystem interactions, such as home–school partnerships, bridge two key and autonomous systems, namely, the school and family. This model identifies the family system as the most influential and proximal context for child development and recognizes the relevance of generating meaningful connections between school and family. These connections are proved to be beneficial for children’s educational success (Bhargava et al., 2017; Wang & Sheikh-Khalil, 2014). These interactions are critical for low-income, disadvantaged families due to the ongoing discontinuities between school and vulnerable communities (Bulotsky-Shearer et al., 2016).

Family involvement has been conceptualized in multiple ways by individual research studies (El Nokali et al., 2010; Fan & Chen, 2001; Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994; Hornby & Lafaele, 2011; Jeynes, 2007; Muhammad et al., 2013; Shute et al., 2011; Tan et al., 2020). Definitions of parental involvement range from the provision of resources by Grolnick and Slowiaczek (1994) or the investment level in the child’s education by LaRocque et al. (2011), to more concrete parental behaviors at home and at school (El Nokali et al., 2010; Fantuzzo et al., 2000). For the present purpose, family involvement is defined as the participation of the primary caregivers in specific activities at home and at school, supporting children’s academic and socio-emotional development (Epstein et al., 2002). This definition references the work of Epstein et al. (2002), a respected scholar in the field of family and school partnerships who formulated a well-established conceptual framework. It focuses on the participation of primary caregivers in activities both at home and at school as well as acknowledges that involvement goes beyond academic tasks to encompass broader aspects of a child's well-being. In addition to that, family involvement is best defined as a multifaceted construct comprising various parenting practices and behaviors (Epstein et al., 2002; Fan & Chen, 2001; Fantuzzo et al., 2000; Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994; Manz et al., 2004). Epstein et al. (2002) empirically supported multidimensional conceptualization continues to be one of the most widely referenced frameworks. As shown in Table 1, this model outlines six concrete types of family involvement behaviors: (1) parenting, (2) home–school communication, (3) volunteering, (4) home learning activities, (5) decision-making within school, and (6) community partnerships.

Although the multidimensional nature of family involvement has been stressed across the literature, this construct is usually narrowly measured focusing solely on school-based behaviors (Manz et al., 2004). This lack of understanding of the variety of ways in which families get involved could have misled investigators to wrongful conclusions on the level of involvement of disadvantaged families. Families with a low socioeconomic status intervene less frequently in school-based activities due to structural barriers such as workplace challenges, lack of time, or economic issues (Alameda-Lawson, 2014; Auerbach, 2012; Fantuzzo et al., 2013; Hampden-Thompson & Galindo, 2017; Wang & Sheikh-Khalil, 2014). Language and cultural differences could also widen the gap between school and vulnerable populations (Calzada and colleagues 2015; McWayne et al., 2015; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018). For the purpose of the present study, we adopt a conceptualization of family involvement as a complex, multidimensional construct that integrates specific components in order to broaden the scope.

Family involvement is thought to decrease as children move up to secondary school and grow up into young adults (Bhargava et al., 2017; Cheung & Pomerantz, 2011; Desforges & Abouchaar, 2003; Spera, 2005). However, various research studies indicate that family involvement is highly influential regardless of the grade level (Suárez Fernández et al., 2011; Taseer et al., 2023; Wilder, 2014). These results are supported by one of the latest meta-analysis in the field by Boonk et al. (2018). It is reported that family involvement does not decrease over time but changes in nature as the child develops. While direct parental behaviors such as support with homework decrease exponentially after the elementary school years, parental educational expectations and aspirations for their children become highly influential as students grow into young adults.

Family involvement and students’ social-emotional development

The implications of family involvement in students’ non-academic outcomes have often been overshadowed by a focus on the academic domain. However, research across disciplines suggest that a wide range of non-cognitive skills or twenty-first-century skills can substantially influence individuals’ educational success and overall well-being, while also impacting the evolving landscape of workforce skills (Kennedy & Sundberg, 2020; Patrinos, 2021; World Economic Forum, 2023). The present study focuses on one type of non-academic attributes which research suggests is currently most critical to navigate in school and beyond: social-emotional development (Chernyshenko et al., 2018). Social-emotional development has been associated with a wide range of outcomes such as higher academic performance (Durlak et al., 2011; Portela-Pino et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2019), improved employability (Guerra et al., 2014) as well as a higher sense of well-being and positive life outcomes (Salmela-Aro & Upadyaya, 2020; Taylor et al., 2017). Social-emotional development is an important basis for students to navigate in and out of school, as supported by extensive literature. When students possess strong social-emotional skills, they are better equipped to resolve conflicts, manage stress, make responsible decisions, and establish positive relationships. By integrating social-emotional development into the school curriculum, schools provide students with the opportunity to develop holistically and contribute to positive classroom climate. Key competences in this domain include self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision-making, relationship skills, and social awareness (CASEL, 2020; Greenberg, 2023; Mestre, 2020).

Numerous research studies provide evidence for the significant and positive association between family involvement and students’ social-emotional development (A. Li et al., 2020; S. Li et al., 2023a, 2023b; Maiya and colleagues 2020; Wong and colleagues 2018). Cosso and colleagues (2022) found notable benefits of family involvement in students’ social-emotional skills from a meta-analysis of 39 parental involvement intervention programs. Parental involvement interventions resulted in positive and moderate effects on students’ academic and non-academic outcomes from preschool to third grade. With regard to domain-specific intervention effects, family involvement positively predicted language–literacy and mathematics outcomes as well as students’ social-emotional skills and behavior problems. In addition to that, Li and colleagues (2023) investigated the influence of home-based parental involvement on the socio-emotional adjustment of middle school students. The study specifically focused on two types of parental involvement, which are communication between parents and adolescents, and the time parents spent with their children. The study involved 8475 Chinese grade 7 students and their parents. The findings indicate that both forms of home-based parental involvement had a positive effect on adolescents' socio-emotional adjustment over time.

Another body of research supports the link between family involvement and students’ social-emotional development while addressing seemingly contradictory findings (Puccioni, 2018; Ray and colleagues 2020; Trost and colleagues 2020; Wang & Cheung, 2023). Parent–teacher cooperation activities positively predicted children’s language and social-emotional skills at the age of 3 (Cohen & Anders, 2019). Regular participation in school meetings resulted in higher levels of receptive language skills and better prosocial behavior of the children. However, this study also suggested a negative link between the occurrence of door-talks between parents and teachers and children’s disruptive behavior. Results from a latent profile analysis by McWayne and Bulotsky-Shearer (2013) revealed that students whose parents reported weekly involvement in educational activities at home were less likely to belong to the extremely dysregulated behavior type and more likely to belong to the socially competent type. In contrast, parents’ involvement in educational activities at home was also associated with students being classified in the inattentive problems type. The different forms of family involvement can serve as predictive factors in students’ social-emotional development. However, they can also indicate that higher levels of family involvement may stem from children’s needs and areas requiring extra support. Together, these studies and many others demonstrate the positive implications of family involvement on students' social-emotional development, emphasizing the significance of fostering robust partnerships between families and schools to support students' holistic development.

School engagement as a potential mediator

This study draws on the school engagement literature in predicting that students’ engagement at school and classroom level will mediate the association between family involvement and students’ social-emotional development. School engagement plays a key role in students' educational success and overall well-being, as highlighted by current research literature (Li & Lerner, 2011; Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, 2013). Numerous studies have revealed the significant impact of school engagement on academic performance (Sukor et al., 2021; Usán Supervía & Salavera Bordás, 2019), on students’ persistence versus dropout (Archambault et al., 2009; Janosz et al., 2008; Wang & Fredricks, 2014) as well as on their personal and cognitive development (Baroody et al., 2016; Grogan et al., 2014). School engagement was defined by Astin (1999) as “the amount of physical and psychological energy that the student devotes to the academic experience” (p. 518). Early works described school engagement as observable student behaviors such as student participation in the academic and extracurricular domain (Brophy, 1983; Natriello, 1984). Students’ emotional reactions about school and learning were subsequently incorporated into the definition broadening the concept of school engagement. These affective reactions can include sense of belonging or interest in school activities, among others (Connell, 1990; Finn, 1989). Recently, aspects of student cognitive engagement have been studied as part of the school engagement literature and relate to the level of psychological investment exerted by students in the learning process (Fredricks and colleagues 2004).

Researchers and scholars have proposed different theoretical models on school engagement including different components or dimensions (Appleton et al., 2006; Finn, 1989; Fredricks and colleagues 2004; Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2011; Reeve & Tseng, 2011; Skinner et al., 2009). However, most of the scientific community now acknowledges that this construct is multifaceted and that a unidimensional conceptualization of school engagement may lead to an oversimplification of the construct. Based on the theoretical work of Fredricks and colleagues (2004), school engagement is described as a complex, multifaceted construct composed of three dimensions: cognitive, behavioral, and emotional engagement. Behavioral engagement refers to students’ participation in school and includes behaviors such as paying attention to the teacher, following school and classroom rules, and the absence of disruptive or problematic behaviors. Emotional engagement encompasses emotional responses to teachers, classmates, or school (e.g., boredom, anxiety, enjoyment, happiness). Cognitive engagement refers to the effort students are willing to put in their schoolwork in order to accomplish a specific learning task and encompasses problem-solving strategies, self-regulation, and metacognitive strategies.

Several key factors contribute to the facilitation of student engagement in school and home settings. Research evidenced the existence of three main contextual predictors that facilitate school engagement: school, family, and peers (Appleton et al., 2006; Sinclair et al., 2003). First, school-level factors such as teacher support, classroom structure, and task characteristics can significantly enhance students’ motivation and involvement in their learning. Students’ individual needs at school including the need for relatedness, autonomy, and competence can play a crucial role in fostering student engagement (Curran & Standage, 2017; Fredricks and colleagues 2004). Furthermore, another key facilitator of student engagement is peer relationships. Peer support has been related to school engagement and active participation in the classroom (Perdue et al., 2009). Conversely, peer rejection or maltreatment has been linked to reduced classroom participation and an inclination to avoid school (Buhs et al., 2006). Lastly, home-level factors such as family involvement and parental structure can encourage students to take an active role in their education and strengthen their sense of ownership. Parental expectations, the value placed in education, and the provision of rules and expectations, among others, can greatly affect student engagement (Appleton et al., 2006; Fernández-Zabala et al., 2016; Raftery et al., 2012; Wigfield et al., 2006). Addressing these facilitators of student engagement offers valuable insight into the extent to which engagement can be influenced by environmental variations. In addition to that, it can help identify particular school and home interventions that yield the most significant effects on behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement.

A significant body of the literature supports the link between school engagement and academic success. Nevertheless, the association between school engagement and non-academic attributes was rarely examined. Li and Lerner (2011) suggested that adolescents across grades 5 to 8 who exhibited the highest levels of behavioral and emotional school engagement tended to be less depressed and were less likely to be involved in delinquent activities, in contrast to their counterparts who displayed more problematic patterns. A research by Upadyaya and Salmela-Aro (2013) revealed a negative association between school engagement and students' well-being, including symptoms of depression and burnout. Staff ratings of student engagement in after-school activities were significantly associated with improvement in social competences within the school setting (Grogan et al., 2014). Multiple approaches to measuring student engagement (i.e., student-, teacher-, and observer-reported measures) revealed significant associations with fifth grade students’ social skills in math class (Baroody et al., 2016). Empirical evidence on the association between school engagement and students’ non-academic attributes has accumulated in the areas of emotional well-being and social competences. Taken together, we presume that school engagement could be a pathway through which family involvement influence students’ social-emotional development.

The present study

Accordingly, the significance of family involvement in explaining the variations in academic achievement and overall well-being among students from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds have been recognized. However, while much attention has been paid to the impact of family involvement on academic outcomes, its implications for students' non-academic outcomes such as social-emotional development have been relatively overlooked. This gap in research highlights the importance of investigating the broader impact of family involvement beyond academic performance, as it may play a crucial role in shaping various aspects of students' social-emotional development.

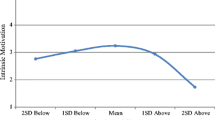

To our knowledge, the potential mediating role of school engagement in the association between family involvement and students’ social-emotional development remains to be explored. There has been little investigation of the mechanisms that explain this association. The present study aimed to investigate whether family involvement was associated with students’ school engagement and social-emotional development and to clarify the underlying mechanism in the relationship between family involvement and social-emotional development. It was expected that family involvement would predict social-emotional development when the effect of students’ school engagement was taken into account. See Fig. 1 for a representation of the hypothesized conceptual model. The hypotheses were formulated below.

-

Hypothesis 1: Family involvement positively and directly predicts students’ socialemotional development

-

Hypothesis 2: Family involvement positively predicts students’ school engagement

-

Hypothesis 3: School engagement positively predicts students’ social-emotional development

-

Hypothesis 4: School engagement mediates the relationship between family involvement and students’ social-emotional development

Methodology

Participants: description of the sample

The present sample consisted of 170 school-aged children and one of their primary caregivers, which corresponds to 170 parents. The total population from which the sample was drawn consists of 264 children and adolescents over the age of 8 years who are enrolled in the CaixaProinfancia program and their primary caregiver. Random sampling was employed to ensure the sample is representative of the population and to enhance the generalizability of the research findings to the larger population. The present sample was selected based on two primary criteria: (1) including 80% of all students and their families enrolled in the program, and (2) beginning with 8-year-olds who met the minimum reading level required to independently complete the questionnaire. However, despite meeting this minimum threshold of 80% during the data collection, some of the data could not be retrieved during the process of linking IDs between parents and children (see the “Procedure” section). This occurred due to discrepancies in ID spellings and other related issues, resulting in the present sample consisting of 170 school-aged children and one of their primary caregivers. The criteria above were decided upon together with the program coordinator from the CaixaProinfancia to ensure alignment with program objectives and ensure operational feasibility.

Participants in this study were selected for the analysis on the basis of their participation within the CaixaProinfancia program in the Basque Autonomous Community in Spain. CaixaProinfancia is a social and educational intervention program run by Obra Social “la Caixa” Foundation. During an initial stage, it was provided in the 10 most populated Spanish regions and with the highest child poverty rates: Balearic Islands, Barcelona, Bilbao, Gran Canaria, Madrid, Malaga, Murcia, Seville, Tenerife, Valencia, and Zaragoza. In the past years, many other Spanish cities have joined the program reaching out the entire Spanish territory. The program is aimed at children and adolescents ranged in age from 1 to 19 years and their families, who live in economically vulnerable situations and experience social exclusion. Families enrolled in the program meet the at-risk-of-poverty threshold established at national level. CaixaProinfancia pursues a holistic development of the participating children and their families through community action networks, and is divided into different services such as psychological support, educational support, and health promotion. The present study includes students across primary and secondary school years in order to identify the different trajectories of family involvement.

Parents or primary caregivers

Parent or primary caregivers participating in this study ranged in age from 26 to 74 years (M = 41.1, SD = 8.9). The sample was 88.2% female and mainly comprised individuals with a migrant background (87% of the sample). The absence of male participants in the sample can be attributed to the focus of the CaixaProinfancia program targeting children and their primary caregivers who actively participate in their education. In the context of CaixaProinfancia program, the active caretakers are the mothers and therefore the ones predominantly participating in the data collection. The overrepresentation of female participants is also linked to the fact that a significant portion of the sample consists of single-parent households headed by mothers. Based on responses on demographic items of the survey, 43.5% of the parents reported secondary education as the highest educational level that they attained, 33.5% reported primary education as the highest educational level attained, and 12.3% reported having completed intermediate or higher level vocational training cycles. Moreover, 8.8% of the parents surveyed reported having attained university studies and 1.7% reported not having completed primary education. Concerning parents’ occupation, the present sample was characterized by the majority of the parents being unemployed and recipients of unemployment benefits (44.1%). In addition, 34.1% of the respondents reported having temporary occupations, 12.3% reported having a permanent job, and a minority of the parents reported being unemployed without receiving any employment benefits. Parents also reported their monthly household income: 49.7% (801 ~ 1.100€), 24.2% (> 1.100€), 18.3% (501 ~ 800€), and 7.6% (< 500€). Table 2 provides demographic data by grade level for the entire primary sample of 170 parents or primary caregivers who provided complete data on the survey.

Primary and secondary school-aged students

Students participating in this study ranged in age from 8 to 17 years (M = 11.3, SD = 2.76), corresponding roughly to the ages of compulsory education. There were 52 students enrolled in primary education and 85 students enrolled in secondary education. For the remaining 33 students, it was not possible to identify whether they were enrolled in primary or secondary education due to the absence of response to the specific question on students’ grade level. Students must be enrolled in school to participate in the CaixaProinfancia program. However, if respondents have not answered specific questions in the self-reported questionnaire such as educational level, it cannot be assigned based on external sources. It is worth mentioning that the data collection procedure, which is explained below, conditioned this identification. The sample was 40.9% female and was mainly composed of students with an immigrant background. The following distinction was made between foreign-born and native-born students based on the OECD distinction (OECD, 2018). Based on students’ responses on demographic items of the survey, 43.6% were first-generation immigrant students (foreign-born students whose parents are both foreign-born), 39.2% of students were second-generation immigrant students (students born in Spain whose parents are both foreign born), 10.1% were native students (students born in Spain whose parents are both native-born), and 6.9% were native students with mixed heritage (students born in Spain who have one native-born and one foreign-born parent).

When completing the survey, students were also asked to indicate the language of schooling. There are three main types of schooling depending on the language of instruction in the Basque Autonomous Community:

-

A language model: Education is entirely in Spanish, with Basque language as a compulsory subject.

-

B language model: Education is mainly in Basque and subjects such as mathematics and literacy are in Spanish.

-

D language model: Education is entirely in Basque, with Spanish language as a compulsory subject.

The present sample was characterized by the majority of students attending D language model (59.1%). Also, 33.1% of students were attending B language model and a minority of 7.6% of students were attending A language model. Table 3 provides demographic data by grade level for the entire primary sample of 170 students who had complete data on the survey.

Measures

The data collection was carried out through the application of three different questionnaires addressed to (1) parents or primary caregivers of primary school-aged students, (2) parents or primary caregivers of secondary school-aged students, and (3) primary and secondary school-aged students. While the questionnaire for parents or primary caregivers varies depending on the age of the students, the questionnaire for students is the same across primary and secondary levels. As shown in Table 4, the present study aims to obtain information on family involvement, student engagement, and students’ social-emotional development.

Family involvement

Family involvement of primary school-aged students was measured using a Spanish adaptation of the Family Involvement Questionnaire – Elementary version (FIQ-E) developed by Manz et al. (2004). In addition to that, family involvement of secondary school-aged students was measured using the Spanish adaptation of the Family Involvement Questionnaire – High School version (FIQHS) by Dueñas et al. (2022). Both of the questionnaires were designed in line with Epstein et al. (2002) empirically supported multidimensional typology of family involvement. Originally, they consisted of three dimensions: (1) home–school communication, (2) home-based involvement, and (3) school-based involvement. The home–school communication factor included the various forms of communication between the primary caregiver and school personnel, ranging from attendance at conferences to phone contact. The home-based involvement factor consisted of the learning activities happening out of school carried out by the primary caregiver, including establishing bedtime routines, having a quiet place to study at home, and discussing personal school experiences. The school-based involvement factor was composed of the different ways in which parents engage in at school such as participating in workshops and volunteering.

For the purposes of the present study, the FIQ-E was translated and adapted into the Spanish language and socio-cultural context and the FIQHS was tested with our concrete socioeconomic sample. This resulted in the following adjustments. Concerning its factor structure, the school-based involvement factor indicated non-positive definite fit suggesting that the three-factor model may not be the most suitable measurement model for family involvement in the Spanish territory, at least for the type of population analyzed in the present study. With this in mind, the best fitting model was a two-factor model consisting of (1) home–school communication and (2) home-based involvement factors, respectively. The response format was adapted to a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). Apart from reformulating the factor structure, items with low factor loadings were eliminated (i.e., < 0.40). As a result, the FIQ-E included 20 items and consisted of (1) home–school communication (12 items; α = 0.92) and (2) home-based involvement factors (8 items; α = 0.83). The FIQHS included 16 items and consisted of (1) home–school communication factor (9 items; α = 0.89) and (2) home-based involvement factor (8 items; α = 0.8).

School engagement

School engagement of primary and secondary school-aged students was measured using the Spanish version of the School Engagement Measure (SEM) by Ramos-Díaz et al. (2016). This is the Spanish adaptation of the School Engagement Measure (SEM) by Fredricks and colleagues (2004). It includes 19 items and consists of three dimensions: (1) behavioral engagement, (2) emotional engagement, and (3) cognitive engagement. The behavioral engagement factor (5 items; α = 0.74) incorporates students’ participation in school such as paying attention to the teacher, following school rules, and the absence of problematic behaviors. The emotional engagement factor (6 items; α = 0.81) encompasses emotional responses to teachers, classmates, or school. The cognitive engagement factor (8 items; α = 0.77) refers to the student’s investment level in the school work and includes individual effort and self-regulation strategies. The response format is a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always).

Social-emotional development

Social-emotional skills and character of primary and secondary students were measured using the Spanish adaptation of the SECDS developed by the authors . This questionnaire is intended to measure different dimensions of students’ social-emotional skills and character. It includes 25 items and consists of six dimensions: (1) prosocial behavior, (2) honesty, (3) self-control, (4) self-development, (5) respect at school, and (6) respect at home. The prosocial behavior factor (5 items; α = 0.71) includes the ability to take the perspective of others and to develop positive and healthy relationship with peers. The honesty factor (4 items; α = 0.66) consists of skills that allow individuals to make appropriate and truthful choices about one’s behaviors and interactions with others. The self-control factor (4 items; α = 0.75) includes the ability to manage one’s thoughts and behaviors in different situations. This includes, for instance, stress management and self-discipline. The self-development factor (4 items; α = 0.76) includes the ability to achieve personal and collective goals. The respect at school factor (4 items; α = 0.81) is composed of the skills required to demonstrate respect for rules and appropriate behavior toward authoritative figures at school settings. The respect at school factor (4 items; α = 0.83) is composed of the ability to demonstrate respect for rules and appropriate behavior toward authoritative figures at home settings. The response format is a 5-point Likert scale (0 = Strongly disagree, 1 = Disagree, 2 = Neutral, 3 = Agree, 4 = Strongly agree).

Procedure

Data collection

All divisions taking part in the CaixaProinfancia program in the Basque Autonomous Community were invited to participate in the survey, and their participation was voluntary. When a division agreed to participate, a contact person was established to coordinate the data collection procedure. To ensure a sufficient sample size per division, program personnel were asked to survey 80% of the total students and their families participating in the program. Participants were selected using a random participant generation procedure targeting students and their families who participated in the CaixaProinfancia program from January to May 2022.

The survey was administered in a small group format during afterschool hours as part of the CaixaProinfancia program and under the supervision of the program personnel. The survey was anonymous and the participants were informed about the right to withdraw from the study at any moment. Total testing time took approximately 20 min. Families and students were encouraged to request the assistance of program personnel if they needed help in answering the items. Program personnel administered an online version of the questionnaire via the Qualtrics platform. Participants read and accepted the informed consent form before accessing and responding the survey.

After the administration of the questionnaire, the data were integrated and prepared for statistical analyses. For data processing purposes, the online version of the questionnaire in Qualtrics included a personalized and anonymized URL for each student and his or her parent. The generation of a personalized URL was done by the program personnel before the administration of the questionnaire. Each URL was composed of the link to the online questionnaire and an anonymized ID (6-digit number). The same ID was employed for each student and his or her parent. This procedure allowed the anonymous linkage of the data of students and the corresponding parent in the analysis. However, given the complexity of the procedure and the unfamiliarity of the participants with it, it was not possible to adequately identify some IDs.

Ethical considerations

This research was conducted with the review and approval of the University of Deusto Research Ethics Committee, the institution at which the authors are affiliated. Appropriate research approvals were also obtained from the families of students participating in the survey and from the officials representing the CaixaProinfancia program in the Basque Autonomous Community.

Data analysis

The analyses were performed using Jamovi statistical software and a GLM Mediation Model module (Gallucci, 2020; The jamovi project, 2022). To address the research objectives of the present study, we first conducted descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of the study variables to assess the linear relationships among these variables. A correlation matrix was performed among all the variables.

Second, we performed a series of mediation analysis to fit the hypothesized relations among the study variables. In the mediation analyses, scores from family involvement were used as predictor variables while scores from students’ social-emotional development were used as the outcome variable. The scores on students’ school engagement were used as the mediator in the model. A general representation of the model can be seen in Fig. 1. In the model, we used the individual components of the constructs of family involvement, school engagement, and social-emotional development to identify their unique contributions to the outcome. A bootstrapping procedure with a 95% confidence interval was employed to assess the statistical significance of the mediation association (indirect effect) between variables (Hayes, 2013).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations among variables

Descriptive statistics and bivariate associations between the variables of interest are displayed in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. The descriptive statistics provide insights into the main variables of school engagement (SE), social-emotional development (SED), and family involvement (FI), as well as their respective dimensions. School engagement encompasses a range of behaviors and attitudes toward schooling, with respondents reporting a moderate level (M = 3.53, SD = 0.708) of engagement on average. Behavioral engagement (M = 4.07, SD = 0.624) and emotional engagement (M = 3.83, SD = 0.983) were rated relatively higher, suggesting active participation and emotional investment in school-related activities. In contrast, cognitive engagement (M = 3.04, SD = 0.860) appeared lower, indicating potential challenges in cognitive aspects of engagement such as critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Social-emotional development emerged as a significant aspect, with respondents reporting relatively high levels (M = 4.07, SD = 0.534) of development in this domain. Regarding the aspects of social-emotional development, the mean scores ranged from 3.64 to 4.18 (SD: 0.601 to 0.958), displaying consistently high levels across all dimensions, with moderate variability in responses. This suggests a positive socio-emotional climate and opportunities for growth in areas such as self-awareness, social skills, and emotional regulation.

Family involvement is another crucial variable, reflecting the extent to which caregivers participate in their children's education and well-being. The mean score for family involvement was moderate (M = 3.64, SD = 0.768), indicating a reasonable level of involvement overall. Dimensions within family involvement, such as home–school communication (M = 3.62, SD = 0.948) and home-based involvement (M = 3.67, SD = 0.914), also demonstrated moderate levels of involvement. These findings suggest that while there is some degree of family involvement, there may be room for improvement in enhancing communication between home and school and increasing parental participation in activities outside of the school setting. Overall, these descriptive statistics shed light on the levels of engagement, social-emotional development, and family involvement among respondents.

The results showed that most of the correlations were in the expected directions. Family involvement (FI) total scores were significantly related to school engagement (SE) total scores (r = 0.188, p = 0.014) but not to social-emotional development (SED) total scores (p = 0.226). When the individual dimensions of SE were examined, FI was only significantly related to the emotional engagement dimension (r = 0.202, p = 0.008) while it was not significantly associated to the two remaining dimensions namely behavioral and cognitive engagement. When accounting for individual SED dimensions, FI scores were not significantly associated with any of SED dimensions (i.e., prosocial behavior, honesty, self-control, self-development, respect at school and respect at home).

In addition to FI total scores, there was a statistically significant association between home-based involvement (HBI) and SE total scores (r = 0.316, p ≤ 0.001) as well as SED total scores (r = 0.215, p = 0.005). When the individual dimensions of SE were examined, HBI was significantly related to all three dimensions of engagement (behavioral engagement r = 0.228, p = 0.003; emotional engagement r = 0.304, p ≤ 0.001; cognitive engagement r = 0.269, p ≤ 0.001). However, the strength of the linear relationship between the correlated variables was the strongest between HBI and SE total scores with the highest correlation coefficients. When accounting for individual SED dimensions, HBI was only significantly associated to prosocial behavior (r = 0.155, p = 0.044) and self-control (r = 0.162, p = 0.035) while it was not significantly associated to the four remaining dimensions (i.e., honesty, self-development, respect at school and respect at home). The strength of the linear relationship between the correlated variables was the strongest between HBI and SED total scores with the highest correlation coefficients. Finally, home–school communication (HSC) was not significantly associated with SE total scores (p = 0.504) nor SED total scores (p = 0.899). Furthermore, HSC was not significantly associated with any of the SE or SED individual dimensions.

Given these findings, the HBI factor was used as a predictor variable in the mediation analyses addressing the present research questions and FI total scores and HSC were discarded. For the same reason, SE total scores were employed as the mediator variable and SED total scores as the outcome variable. Individual dimensions of SE and SED were discarded for the present analysis, as their unique contribution to the analysis based on their correlation coefficient was weaker than the corresponding total score.

Mediation effect analysis

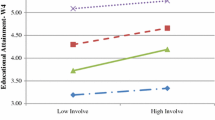

Mediation analysis was performed to assess the mediating role of school engagement on the association between home-based family involvement and students’ social-emotional development, as indicated in the hypothesized model. The coefficients presented in Table 7 showed that the total effect of home-based family involvement on students’ social-emotional development was significant (β = 0.215, p = 0.004, 95% CI [0.03, 0.21]). The total effects represent the effects calculated without the mediators, or, alternatively, they can be understood as the sum of the indirect and the direct effects.

Hypothesis 1: Family involvement directly and positively predicts students’ social-emotional development

Findings indicated that the direct effect of home-based family involvement on students’ social-emotional development was not statistically significant. Specifically, the direct effect yielded a non-significant coefficient (β = − 0.028, p = 0.543, 95% CI [− 0.07, 0.03]). The direct effects represent the effects calculated holding the mediators constant, thereby reflecting the un-mediated effects. This suggests that home-based involvement did not exert a direct influence on students’ social-emotional development. Consequently, Hypothesis 1, positing a direct and positive relationship between family involvement and students’ social-emotional development, was not supported by the findings.

Hypothesis 2: Family involvement positively predicts students’ school engagement

The analysis revealed a positive association between home-based family involvement and students’ school engagement. Increased levels of family involvement were significantly associated with higher levels of students’ school engagement (β = 0.316, p ≤ 0.001, 95% CI [0.12, 0.36]). This result supports Hypothesis 2, indicating that family involvement predicts higher levels of school engagement among students.

Hypothesis 3: School engagement positively predicts students’ social-emotional development

Furthermore, the analysis demonstrated a positive relationship between school engagement and students’ social-emotional development. Students with higher scores in school engagement exhibited greater social-emotional development (β = 0.769, p ≤ 0.001, 95% CI [0.49, 0.65]). This finding provides support for Hypothesis 3, indicating that school engagement is positively associated with students’ social-emotional development.

Hypothesis 4: School engagement mediates the relationship between family involvement and students’ social-emotional development

Finally, the indirect effect of family involvement on students’ social-emotional development through school engagement was examined. The results showed that the indirect effect of family involvement on students’ social-emotional development through school engagement was significant (β = 0.243, p ≤ 0.001, 95% CI [0.07, 0.21]), accounting for 82% of the total effect of family involvement on students’ social-emotional development. Conversely, the direct effect of family involvement on students’ social-emotional development, calculated without the mediator, was not significant as supported by Hypothesis 1. This indicates that the impact of family involvement on students’ social-emotional development is fully mediated by students’ school engagement, providing support for Hypothesis 4. The resulting mediation model is presented in Fig. 2.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to determine the association of family involvement with students’ social-emotional development, and examine whether school engagement mediated the relationship between family involvement and students’ social-emotional development. The mediational analysis suggested that home-based family involvement could not predict directly students’ social-emotional development, and that the effect of home-based family involvement on students’ social-emotional development was fully mediated by school engagement, a variable not included in previous research. The present results provide valuable insights into the effects of family involvement on students’ non-academic attributes and shed light on the underlying mechanism that intervenes in this relationship.

The mediating role of school engagement

Our study provides evidence for the mediating role of students’ school engagement in the relationship between home-based family involvement and students’ social-emotional development. The results highlight significant indirect effects of home-based family involvement on students’ social-emotional development via school engagement. This finding expands on those of previous studies reporting the mediating effects of school-related processes in the association between family involvement and children’s social-emotional development.

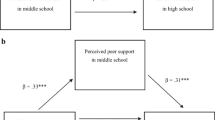

Li and colleagues (2023) delved into the intricate relationship between home learning environment and children’s social-emotional competence. In their model, internal elements of home learning environment such as structural family characteristics and parents’ educational beliefs and interests served as independent variables, educational processes as mediating variables, and children’s social-emotional competence as the dependent variable. Their findings revealed significant positive predictive effects of both structural family characteristics and parental beliefs and interests on children’s social-emotional competence. Interestingly, the educational processes emerged as mediating the relationship between structural family characteristics, parental beliefs and interests, and children’s social-emotional competence. In addition to that, Wong and colleagues (2018) investigated the associations between parental educational involvement both at home and in school with the academic performance and psychosocial development of 507 Chinese Grade 3 schoolchildren in Hong Kong. Psychosocial development was assessed across five domains: conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, emotional problems, peer relationship problems, and positive prosocial behaviors. The study explored the underlying mechanism by examining school engagement as a mediator in these relationships. The findings indicated a positive association between home-based parental involvement and children’s psychosocial well-being, with these associations mediated by engaging children with school. Specifically, home-based parental involvement directly impacted children’s prosocial behaviors and also exerted an indirect influence through children’s school engagement.

Similar patterns were observed in the study conducted by Li and colleagues (2020), indicating the mediation effect of the association between parent involvement in schools and middle-school-aged students’ social-emotional development. Their study, involving 1062 Chinese adolescents, revealed that parent involvement in schools was linked to increased prosocial behaviors and reduced problem behaviors. Positive coping, measured through problem-solving, seeking social support, and positive rationalization, emerged as a mediating factor. Interestingly, parent involvement in schools positively influenced positive coping, which, in turn, was positively associated with prosocial behaviors and negatively correlated with problem behaviors. In their study, Maiya and colleagues (2020) also investigated the mediating influences of deviant peer affiliation and school connectedness in the relationship between parental involvement and prosocial behaviors among US Latino/a adolescents. Through path analysis, they found that parental involvement had both direct and indirect associations with prosocial behaviors, mediated by both deviant peer affiliation and school connectedness. Specifically, parental involvement was linked to lower levels of deviant peer affiliation, which, in turn, correlated with greater school connectedness. This increased school connectedness, in further consequence, was associated with increased levels of prosocial behaviors.

Compared to these earlier investigations, our research provides additional insights into the impact of home-based parental involvement on students' social-emotional development, revealing a pathway fully mediated by school engagement. This full mediation is characterized by the complete explanation of the relationship between home-based parental involvement and social-emotional development through school engagement. As a result, the effects of home-based involvement on social-emotional development become non-significant when the mediator is included in the model. This finding suggests that when families are actively engaged in their child's education at home, it positively influences students' level of participation in school, which, in turn, promotes the development of social-emotional competences in primary and secondary school-aged students. We hypothesize a few reasons for this phenomenon: first, the learning activities happening outside school carried out by the primary caregiver, including providing support with schoolwork and discussing personal school experiences, play a fundamental role in shaping the way students interact and participate in school. Home-based family involvement highlights the value of school that will be internalized by the student and thus contribute to increase the student’s level of investment in school as well as improve their emotional responses to teachers, classmates, and school. Furthermore, students’ successful participation in school setting equips them to resolve conflicts, manage stress, make responsible decisions, and establish positive relationships, which, in turn, shapes students’ social-emotional development.

Effects of family involvement on students’ social-emotional development

Contrary to the findings of Li and colleagues (2023), our study suggested that home-based family involvement was not directly associated with students’ social-emotional development. The involvement of families in their child's education, including bedtime routines, having a quiet place to study at home, and discussing personal school experiences, did not predict directly students' social-emotional development. This finding is consistent with other investigations that found no statistical significant correlation between these variables or negative effects on students' social-emotional development and address seemingly contradictory findings.

Puccioni (2018), drawing upon data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, determined that increased parental participation in home-based activities correlated positively with children’s social skills. Nevertheless, their research did not reveal a link between parents' home-based involvement and children's self-regulatory skills. In addition to that, Ray and colleagues (2020) examined the impact of a preschool-based family-involvement intervention on children’s cognitive and emotional self-regulation skills. No differences were observed in self-regulation skills between the intervention group and the control group in their preschool-based family-involving intervention program.

In the investigation led by Wang and Cheung (2023), comparable trends were noted, providing partial support for mother and father involvement being related to higher levels of child adjustment. More precisely, mother and father involvement showed a positive correlation with children’s prosocial behavior. Nonetheless, mother and father involvement did not demonstrate a significant relationship with children’s behavioral problems. Similarly, Trost and colleagues (2020) found that democratic parenting characterized by parents’ openness to adolescents’ viewpoints and parental warmth displayed negative associations with behavioral constructs such as problematic peer relationships and behavioral problems, while parental warmth showed a non-significant association. Results from a latent profile analysis by McWayne and Bulotsky-Shearer (2013) concluded that students whose parents reported weekly involvement in educational activities at home were more likely to belong to the socially competent type but were also more likely to belong to the inattentive problems type. The socially competent type showed strong cognitive and social skills with positive learning attitudes, while the inattentive type exhibited low attention and negative learning attitudes along with hyperactive behavior. Overall, these findings may be counterintuitive at first but considering existing research on the matter, it can be assumed that children with behavioral and emotional needs may necessitate increased parental involvement.

While our results align with previous studies, there are some differences in the underlying mechanisms and implications highlighted in our study. These findings could be explained in light of the characteristics of our sample. The present sample is composed of students and their families who live in economically vulnerable situations and experience social exclusion. This is consistent with prior research suggesting that families belonging to a lower socioeconomic status (SES) tend to participate less frequently in school-based activities, primarily due to structural barriers such as workplace demands, time constraints, or economic issues (Hampden-Thompson & Galindo, 2017; McWayne & Melzi, 2014; Nyemba & Chitiyo, 2018; Wang & Sheikh-Khalil, 2014). In a study by Calzada and colleagues (2015), they showed that acculturation and enculturation among immigrant parents living in the USA predicted home- and school-based family involvement. Families who were connected to their origin culture as well as the US mainstream culture showed higher levels of home- and school-based involvement.

Limitations and future research

The present findings should be considered in light of the following limitations. First, this study relied on self-reported measures, which may introduce biases in the form of participants’ subjectivity and social desirability effects. Future research should incorporate additional types of assessment and sources of information including third-party raters and direct observations. Second, our data set comprised socioeconomically and ethnically diverse, low-income students and their parents. Although this data set provides concrete insights to better understand and address the unique challenges of these vulnerable populations, future investigations are necessary to confirm the association between the study variables with variety of socioeconomic and ethnic profiles. This will serve to further validate the conclusions that can be drawn from this study and clarify the effects of family involvement on students’ non-academic attributes.

Implications for policy and practice

The mediating role of school engagement in the relationship between home-based family involvement and students’ social-emotional development has not been examined in earlier works, and we considered it noteworthy given the relevance of social-emotional development in primary and secondary school-aged students. To our knowledge, this is the first study that examines a mechanism by which family involvement is related to a child’s social-emotional development through school engagement. Accordingly, the present findings prove the interconnectedness of home-based family involvement, students’ school engagement, and social-emotional development, highlighting the need for more collaborative efforts between family and school in order to maximize students' social-emotional growth.

Furthermore, the present results point at the factors of family involvement that yielded school engagement the most among low-SES families and thus provide useful information on which factors should be addressed in home–school interventions. We ought to shed light on the capacity and the variety of ways in which low-income families get involved as well as underscore potential poverty-related barriers to family involvement in order to avoid wrongful conclusions on the level of involvement of disadvantaged families. The present study advances research on the different ways low-SES families get involved and therefore provides practical information for the future professionalization of parent–school cooperation. It also highlights the benefits of home-based parental involvement for the school engagement in primary and secondary school-aged students.

Data availability

The data necessary to reproduce the analyses presented here is not publicly accessible. Similarly, the materials necessary to attempt to replicate the findings presented here are not publicly accessible. The analyses presented here were not preregistered.

References

Alameda-Lawson, T. (2014). A pilot study of collective parent engagement and children’s academic achievement. Children & Schools, 36(4), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdu019

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., Kim, D., & Reschly, A. L. (2006). Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the Student Engagement Instrument. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.04.002

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Morizot, J., & Pagani, L. (2009). Adolescent behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement in school: Relationship to dropout. Journal of School Health, 79(9), 408–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00428.x

Astin, A. W. (1999). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Development, 40(5), 518–529.

Auerbach, S. (2012). Conceptualizing leadership for authentic partnerships: A continuum to inspire practice. In S. Auerbach (Ed.), School leadership for authentic family and community partnerships: Research perspectives for transforming practice (pp. 29–51). Routledge.

Ayllón, S., Brugarolas, P., & Lado, S. (2022). La transmisión intergeneracional de la pobreza y desigualdad de oportunidades en España. Ministerio de Derechos Sociales y Agenda 2030. https://www.mdsocialesa2030.gob.es/derechos-sociales/inclusion/contenido-actual-web/transmision_intergeneracional_pobreza.pdf

Baroody, A. E., Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Larsen, R. A., & Curby, T. W. (2016). A multi-method approach for describing the contributions of student engagement on fifth grade students’ social competence and achievement in mathematics. Learning and Individual Differences, 48, 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.02.012

Benner, A. D., Boyle, A. E., & Sadler, S. (2016). Parental involvement and adolescents’ educational success: The roles of prior achievement and socioeconomic status. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(6), 1053–1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0431-4

Bhargava, S., Bámaca-Colbert, M. Y., Witherspoon, D. P., Pomerantz, E. M., & Robins, R. W. (2017). Examining socio-cultural and neighborhood factors associated with trajectories of Mexican-origin mothers’ education-related involvement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(8), 1789–1804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0628-6

Boonk, L., Gijselaers, H. J. M., Ritzen, H., & Brand-Gruwel, S. (2018). A review of the relationship between parental involvement indicators and academic achievement. Educational Research Review, 24, 10–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.001

Broer, M., Bai, Y., & Fonseca, F. (2019). Socioeconomic achievement gaps: Trend results for education systems. In IEA Research for Education (5). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11991-1_4

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol 1, Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). Wiley.

Brophy, J. E. (1983). Research on the self-fulfilling prophecy and teacher expectations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(5), 631–661. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.75.5.631

Buhs, E., Ladd, G., & Herald, S. (2006). Peer exclusion and victimization: Processes that mediate the relation between peer group rejection and children’s classroom engagement and achievement? Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.1

Bulotsky-Shearer, R. J., Bouza, J., Bichay, K., Fernandez, V. A., & Gaona Hernandez, P. (2016). Extending the validity of the Family Involvement Questionnaire-Short Form for Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Families from Low-Income Backgrounds. Psychology in the Schools, 53(9), 911–925. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21953

Calzada, E. J., Huang, K. Y., Hernandez, M., Soriano, E., Acra, C. F., Dawson-McClure, S., Kamboukos, D., & Brotman, L. (2015). Family and teacher characteristics as predictors of parent involvement in education during early childhood among Afro-Caribbean and Latino immigrant families. Urban Education, 50(7), 870–896. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085914534862

CASEL. (2020). What Is SEL? | CASEL District Resource Center. Retrieved June 9, 2023 from https://drc.casel.org/what-is-sel/

Castro, M., Expósito-Casas, E., López-Martín, E., Lizasoain, L., Navarro-Asencio, E., & Gaviria, J. L. (2015). Parental involvement on student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 14, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.01.002

Chernyshenko, O. S., Kankaraš, M., & Drasgow, F. (2018). Social and emotional skills for student success and well-being: Conceptual framework for the OECD study on social and emotional skills. OECD Education Working Papers, 173, 1–136. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/social-and-emotional-skills-for-student-success-and-well-being_db1d8e59-en

Cheung, C. S. S., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2011). Parents’ involvement in children’s learning in the United States and China: Implications for children’s academic and emotional adjustment. Child Development, 82(3), 932–950. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01582.x

Chmielewski, A. K. (2019). The global increase in the socioeconomic achievement gap, 1964 to 2015. American Sociological Review, 84(3), 517–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419847165

Cohen, F., & Anders, Y. (2019). Family involvement in early childhood education and care and its effects on the social-emotional and language skills of 3-year-old children. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 31(1), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2019.1646293

Connell, J. P. (1990). Context, self, and action: A motivational analysis of self-system processes across the life span. In D. Cicchetti & M. Beeghly (Eds.), The self in transition: Infancy to childhood (pp. 61–97). University of Chicago Press.

Cosso, J., von Suchodoletz, A., & Yoshikawa, H. (2022). Effects of parental involvement programs on young children’s academic and social-emotional outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of family psychology : JFP : journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 36(8), 1329–1339. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000992

Criado, E. M., & Bueno, C. G. (2017). El mito de la dimisión parental Implicación familiar, desigualdad social y éxito escolar. Cuadernos, 35(2), 305–325. https://doi.org/10.5209/CRLA.56777

Curran, T., & Standage, M. (2017). Psychological needs and the quality of student engagement in physical education: Teachers as key facilitators. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 36(3), 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.2017-0065

Davis-Kean, P. E. (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.294

Dearing, E., Kreider, H., Simpkins, S., & Weiss, H. B. (2006). Family involvement in school and low-income children’s literacy: Longitudinal associations between and within families. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(4), 653–664. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.653

Desforges, C., & Abouchaar, A. (2003). The impact of parental involvement, parental support and family education on pupil achievements and adjustment: A literature review. Education, 30(8), 1–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2004.06.001

Domina, T. (2005). Leveling the home advantage: Assessing the effectiveness of parental involvement in elementary school. Sociology of Education, 78(3), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/003804070507800303

Driessen, G., Smit, F., & Sleegers, P. (2005). Parental involvement and educational achievement. British Educational Research Journal, 31(4), 509–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920500148713

Dueñas, J. M., Morales-Vives, F., Camarero-Figuerola, M., & Tierno-García, J. M. (2022). Spanish adaptation of the Family Involvement Questionnaire - High School: Version for Parents. Psicología Educativa, 28(1), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2020a21

Dumont, H., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Neumann, M., Niggli, A., & Schnyder, I. (2012). Does parental homework involvement mediate the relationship between family background and educational outcomes? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 37, 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.09.004

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

El Nokali, N. E., Bachman, H. J., & Votruba-Drzal, E. (2010). Parent involvement and children’s academic and social development in elementary school. Child Development, 81(3), 988–1005. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01447.x

Epstein, J. L., Mavis, G. S., Beth, S. S., Karen, C. S., Jansorn, N. R., & Voorhis, F. L. V. (2002). School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action. Second Edition. Corwin Press.

Erdem, C., & Kaya, M. (2020). A meta-analysis of the effect of parental involvement on students’ academic achievement. Journal of Learning for Development, 7(3), 367–383.

Fan, X., & Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 13(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009048817385

Fantuzzo, J., Tighe, E., & Childs, S. (2000). Family involvement questionnaire: A multivariate assessment of family participation in early childhood education. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(2), 367–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.2.367

Fantuzzo, J., Gadsden, V., Li, F., Sproul, F., McDermott, P., Hightower, D., & Minney, A. (2013). Multiple dimensions of family engagement in early childhood education: Evidence for a short form of the Family Involvement Questionnaire. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(4), 734–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.07.001

Fernández-Zabala, A., Goñi, E., Camino, I., & Zulaika, L. M. (2016). Family and school context in school engagement. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 9(2), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejeps.2015.09.001

Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59(2), 117–142. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543059002117

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Gallucci, M. (2020). jAMM: jamovi Advanced Mediation Models. [jamovi module]. Retrieved from https://jamovi-amm.github.io/

Greenberg, M. T. (2023). Evidence for social and emotional learning in schools. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/928.269

Grogan, K. E., Henrich, C. C., & Malikina, M. V. (2014). Student engagement in after-school programs, academic skills, and social competence among elementary school students. Child Development Research, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/498506

Grolnick, W. S., & Slowiaczek, M. L. (1994). Parents’ involvement in children’s schooling: A multidimensional conceptualization and motivational model. Child Development, 65(1), 237. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131378

Guerra, N., Modecki, K., & Cunningham, W. (2014). Developing Social-Emotional Skills for the Labor Market: The PRACTICE Model (No. 7123; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series).

Hampden-Thompson, G., & Galindo, C. (2017). School–family relationships, school satisfaction and the academic achievement of young people. Educational Review, 69(2), 248–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2016.1207613

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12050

Hill, N. E., & Tyson, D. F. (2009). Assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental Psychology, 45(3), 740–763. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015362.Parental

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Battiato, A. C., Walker, J. M. T., Reed, R. P., DeJong, J. M., & Jones, K. P. (2001). Parental involvement in homework. Educational Psychologist, 36(3), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3603_5

Hornby, G., & Lafaele, R. (2011). Barriers to parental involvement in education: An explanatory model. Educational Review, 63(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2010.488049

Janosz, M., Archambault, I., Morizot, J., & Pagani, L. S. (2008). School engagement trajectories and their differential predictive relations to dropout. Journal of Social Issues, 64(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00546.x

Jeynes, W. H. (2007). The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Urban Education, 42(1), 82–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085906293818

Jury, M., Smeding, A., Stephens, N. M., Nelson, J. E., Aelenei, C., & Darnon, C. (2017). The experience of low-SES students in higher education: Psychological barriers to success and interventions to reduce social-class inequality. Journal of Social Issues, 73(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12202

Kennedy, T. J., & Sundberg, C. W. (2020). 21st Century Skills. In: B. Akpan & T. J. Kennedy (Eds.). Science education in theory and practice: An introductory guide to learning theory (pp. 479–496). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43620-9_32

Khajehpour, M., & Ghazvini, S. D. (2011). The role of parental involvement affect in children’s academic performance. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 1204–1208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.263

LaRocque, M., Kleiman, I., & Darling, S. M. (2011). Parental involvement: The missing link in school achievement. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 55(3), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10459880903472876

Lawson, G. M., & Farah, M. J. (2017). Executive function as a mediator between SES and academic achievement throughout childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(1), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415603489

Lechner, C. M., Bender, J., Brandt, N. D., & Rammstedt, B. (2021). Two forms of social inequality in students’ socio-emotional skills: Do the levels of big five personality traits and their associations with academic achievement depend on parental socioeconomic status? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 679438. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.679438

Li, Y., & Lerner, R. M. (2011). Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence: Implications for grades, depression, delinquency, and substance use. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021307

Li, Q., Cao, Z., & Zhao, D. (2023). Home-based parental involvement and early adolescents’ socio-emotional adjustment at middle school in China: A longitudinal exploration of mediating mechanisms. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(7), 2153–2163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02594-0

Li, S., Tang, Y., & Zheng, Y. (2023). How the home learning environment contributes to children’s social-emotional competence: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1065978. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1065978

Li, A., Wang, S. & Liu, X. (2020). Parent involvement in schools as ecological assets, prosocial behaviors and problem behaviors among Chinese middle school students: Mediating role of positive coping. Current Psychology, 42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01098-0

Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Rogat, T. K., & Koskey, K. L. (2011). Affect and engagement during small group instruction. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.09.001

Llano Ortiz, J. C., Alba, L., Alguacil, A., Jiménez, N., & Quiroga, D. (2020). El estado de la pobreza. Seguimiento del indicador de pobreza y exclusión social en España 2008–2019. Red Europea de Lucha Contra La Pobreza y La Exclusión Social En España. https://www.eapn.es/estadodepobreza/ARCHIVO/documentos/Informe_AROPE_2020_Xg35pbM.pdf

Maiya, S., Carlo, G., Gülseven, Z., & Crockett, L. (2020). Direct and indirect effects of parental involvement, deviant peer affiliation, and school connectedness on prosocial behaviors in U.S. Latino/a youth. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(10–11), 2898–2917. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520941611

Manz, P. H., Fantuzzo, J. W., & Power, T. J. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of family involvement among urban elementary students. Journal of School Psychology, 42(6), 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2004.08.002

McWayne, C. M., & Bulotsky-Shearer, R. J. (2013). Identifying family and classroom practices associated with stability and change of social-emotional readiness for a national sample of low-income children. Research in Human Development, 10(2), 116–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2013.786537

McWayne, C. M., & Melzi, G. (2014). Validation of a culture-contextualized measure of family engagement in the early learning of low-income Latino children. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(2), 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036167