Abstract

Educators have incorporated technologies designed to “gamify” or increase the fun and reward of classroom learning, but little is known about how these resources can be employed to create positive learning climates. Informed by self-determination theory (SDT), two experiments investigated a number of strategies teachers can use to frame one such technology, the student response system (SRS), when they use it as an educational tool to enhance its fun and contribution to positive learning environments. Participants (n = 30) in a pilot experiment were randomly assigned to a 2-month experiment that showed that using SRS versus non-technology-based learning increases academic well-being. A primary study (n = 120 students) experimentally manipulated the use of SRS with and without motivational framing strategies that were anticipated to enhance its effects, specifically by employing teamwork, friendly competition between students, and giving students a choice to participate. Results showed that motivational framing strategies enhanced students’ need satisfaction for autonomy (sense of choice), competence (sense of efficacy in relation to learning), relatedness (to others in the classroom), and academic well-being (interest and engagement). In short, the use of interactive technology and how it was implemented in class was vital for enhancing students’ learning outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Technology is increasingly used in educational contexts (Fernández & Jácome, 2016; Parra-González et al., 2020), across academic levels from early ages to university students (Parra-González et al., 2020). This is not new; games have been implemented in classrooms since the 1960s to engage students in learning (Piaget, 2013). Over time, more game structures and elements are employed when using forms of technology in formal educational environments (Fernández & Jácome, 2016). It is now recognized that technology can be used to “gamify” learning by promoting fun in the classroom (Zainuddin et al., 2020).

Gamification involves adapting game techniques and designs to non-game environments to solve problems more effectively and to increase the interest and involvement of users (Werbach & Hunter, 2012). The pedagogical practice aims to promote academic well-being in the classroom (O’Brien, 2016) through contributing to students’ interest in specific classroom tasks (Perez-Manzano & Almela-Baeza, 2018) and supporting their engagement and effort in building academic knowledge (Xi & Hamari, 2019). Adapting gamification in the classroom, students are encouraged to actively engage in the learning process, to ultimately enhance academic outcomes (Groening & Binnewies, 2019). When a user voluntarily participates in the gamified activity, they experience more constructive intrinsic motivation that further shapes their learning behavior (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019).

Gamification can be incorporated into learning with or without the use of technology (Mee Mee et al., 2020). However, educators can use technological tools to provide students with more diverse and interactive learning environments (Huang & Hew, 2021) that are especially effective in engaging students (Qiao et al., 2023). Technology can therefore be thought of as a set of tools among others that can enhance the learning environment.

One gamified device that can be used in the classroom is the student response system (SRS; Liu et al., 2019)—a system that provides a handheld device called a “clicker” to every student (Caldwell, 2007). This device enables students to simultaneously respond to a question that is projected on the whiteboard by the teacher who also uses a clicker. The SRS provides a form of “experiential learning” which transforms education through eliciting active engagement with materials, providing repeated practice that assists in processing, and utilizing experiences to access knowledge (Moore et al., 2018). In ideal conditions, it stimulates interest, the desire and predisposition to engage with specific contents like objects and tasks (Smith & Abrams, 2019).

For the purpose of this paper, the gamified student response system (SRS)—a tool of experiential learning—will be referred to as gamified experiential technology (GET), recognizing that SRS is just one indicator which we anticipated could extend to other gamified devices such as a smartphone or tablet that can be used as a student response system—if an app is downloaded—and equally promote experiential learning (Fithriani, 2021; Kaimara et al., 2019). Mobile apps are being increasingly used: In 2022, there were 255 billion app downloads as compared to 140.7 billion in 2016, an 80% increase (though the majority are used for gaming rather than educational reasons; Statista, 2023). Using a mobile app on each student’s mobile instead of a clicker can reduce the cost of a classroom as SRS can be expensive and time-intensive to buy and maintain (Álvarez et al., 2017). However, for the purpose of this paper, we relied on SRS to understand children’s and adolescents’ learning because few students aged 9 to 16 years of age own, or are permitted to bring to school, their own mobile phones (Liu & Lai, 2023).

We utilized the self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2002, 2017), a framework that postulates three basic psychological needs, for autonomy, relatedness, and competence, and underlying academic well-being indicators such as interest and effort (Francisco-Aparicio et al., 2013; Peter et al., 2019; Ryan & Deci, 2002, 2020). The first of the basic psychological needs, autonomy, involves having the experience that one’s behavior is driven by will or volition to perform a task based on interest and without pressure, coercion, or direct incentivization by others (Deci & Ryan, 2012; Vansteenkiste et al., 2010, 2012).

Second, relatedness refers to the experience that one has of closeness, trust, and companionship with peers, such as with other students or a teacher. Students experience academic well-being when they feel secure learning and performing in the presence of other close and supportive peers (Deci & Vansteenkiste, 2004; Francisco-Aparicio et al., 2013). Third, competence need satisfaction refers to the experience that one is effective when undertaking tasks and challenges. Students feel competent when they take on interesting challenges within their skillset and receive constructive performance-focused feedback in relation to their own learning goals. Such feelings of competence are vital for continued engagement in and out of the classroom (Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013).

Strategies in gamified experiential technology

Applying SDT to the use of GET classroom technology such as the SRS, the three basic psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competence can be enhanced through modulating specific game elements. We posit different activity framing strategies—teamwork, friendly competition salient, choice, and anonymity—that can be used by teachers as they engage children in experiential technologies to enhance the three basic psychological needs. These framing strategies are designed to motivate students; that is, they provide a context for technology use that inspires students to engage with and enjoy the learning activity.

Autonomy refers to the experiences of decision freedom and task meaningfulness and is supported when students have the freedom of choice (Peng et al., 2012) and experience their participation as a volitional and meaningful engagement (Montessori et al., 2017; Rathunde & Csikszentmihalyi, 2005; Rigby & Ryan, 2011). Using technology, educators can take the opportunity to build choice into their tasks to enhance the sense that students can opt in volitionally to the task, an important quality for promoting autonomy need satisfaction (Leo et al., 2022; Rissanen et al, 2023; Ryan & Deci, 2017). Choice allows for all students to have meaningful options about what and when to study or how they may participate, irrespective of whether they have any special requirements or not (Anderson, 2016). Research on choice provision has shown that it is associated with motivation, task performance, engagement, and a preference for challenge and learning (Patall et al., 2008, 2010).

To support relatedness, the student can be given a meaningful collaborative role to play (Sailer et al., 2017); teamwork allows students to work together as one unit to succeed in their goal (Groh, 2012). Allowing students to collaborate before responding to a question with a clicker increases active engagement and improves academic performance in the classroom (Shadiev & Yang, 2020).

Finally, the need of competence can be supported by friendly competition with the aid of the leaderboard, bar chart, and points (Bai et al., 2021), made possible because the technology gives feedback connected directly to students’ performance, progress over time, and actions (Rigby & Ryan, 2011). For this to be successful, the game should not promote ego-based competition but rather act more like a board game that helps students challenge themselves, have fun, and get positive feedback about their engagement, regardless of their performance (Akram & Abdelrady, 2023; Triantafyllakos et al., 2011). In a survey of students, for example, Pettit et al. (2015) found that friendly peer competition elicited the highest engagement in SRS learning during tiresome routine activities. In non-combative circumstances, having competition in the classroom is stimulating, and friendly peer competition is particularly engaging (Lehman et al., 2012). Research has shown that controlling or negative feedback can thwart competence (Na & Han, 2023), but intangible rewards which are also task-contingent provide positive feedback for the students to improve and master the task (Davis & Singh, 2015). Other studies have also indicated positive outcomes (Bai et al., 2021; Christy & Fox, 2014; David & Weinstein, 2023; Landers et al., 2017; Landers & Landers, 2014; Pettit et al., 2015).

Together, these three pedagogical strategies may map onto psychological need satisfaction. The freedom of choice to participate in GET supports autonomy, teamwork offers a sense of connection to other students that can satisfy relatedness, and friendly competition can help provide constructive and fun performance feedback that can satisfy competence (Stroet et al., 2013; Vasconcellos et al., 2020).

Present research

Empirical research on the effects of game elements on psychological need satisfaction is limited (Bitrián et al., 2021; although recent studies do call for more understanding of engagement with gamification; Fang et al., 2017; Ho & Chung, 2020). In the domain of education (Kasurinen & Knutas, 2018; Koivisto & Hamari, 2019; Seaborn & Fels, 2015), identify the need for more advanced classroom technology that adapts to modern students’ needs (Montazami et al., 2022; Young, 2016). Furthermore, technology should be fit for purpose. Otherwise, students may misuse the technology or may be distracted (Miller, 2012; Reichert & Mouza, 2018). Another critique of gamification apps is that they depend on the contingent and decontextualized utilization of external rewards which may reduce motivation (Ryan et al., 2021); more internalized forms of motivation should be encouraged to drive sustained learning (Kam & Umar, 2018). The SRS provides a distinct advantage as a fit-for-purpose teaching tool which offers little opportunity for distraction, but studies using SRS have to date been conducted primarily on university students (Benson et al., 2017; Çelik & Baran, 2022; Pearson, 2017) or in one cross-sectional study (Sun & Hsieh, 2018) with seventh-grade students.

Learning methods that support need satisfaction enhance learners’ academic well-being, which in turn increases participation and engagement in the learning process (Lei, 2010; Nikou & Economides, 2016), enjoyment, and academic performance (Li & Chu, 2021).

By evaluating GET with the lens of the SDT, we can explore ways to increase academic well-being indicators closely linked to intrinsic motivation to engage learning (Deci & Ryan, 2016). Our first indicator of academic well-being, interest in learning, refers directly to intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Utilizing adequate technologies can enhance student interest (Parong & Mayer, 2018), which motivates students from within, reflecting their natural instincts to learn (Dohn et al., 2016). The second, effort, refers to the willingness a student has to invest in the learning activity (Bai & Wang, 2023; Dunlosky et al., 2020; Malone & Lepper, 2021).

To understand the role of GET, we first conducted a pilot study to test the effects of GET uses on academic well-being, operationalized as students become interested in the lesson and show perceived effort in the learning activities. The main experiment (study 1) was designed to build on the conceptual model testing academic well-being in the pilot study by exploring psychological need satisfaction as a link between GET use and academic well-being and to compare positive motivational framing (specifically, teamwork, friendly competition, and choice) for delivering GET.

Hypotheses

Technology use in the classroom can make learning more interactive, engaging, and fun for students, but the way that technology is used by teachers—framed in gamified ways that support psychological needs or simply as another classroom activity—may drive its potential benefits. These assumptions have not been sufficiently tested, and the current research sets out to test them experimentally in classrooms randomly assigned to receiving technology-based or traditional learning (pilot study) and to motivationally framed learning (employing teamwork, friendly competition, and choice) or technology-based learning in the absence of motivational framing (study 1). These two naturalistic experiments provide the basis for drawing causal conclusions about the impacts of these educational tools on students’ psychological needs and academic well-being. Hypotheses were pre-registered prior to study 1 data collection, along with a planned design and analytic approach (https://osf.io/phgs3/). SDT posits that supporting one psychological need (e.g., autonomy) activates another (e.g., relatedness), and indeed, they show high correlations in previous research (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Su & Reeve, 2011). Therefore, we did not set specific a priori hypotheses pitting one need against another. We hypothesized that.

-

H1a. When the students are assigned to the teamwork condition, they will report higher basic psychological need satisfaction as compared to the traditional learning condition.

-

H1b. When the students are assigned to the teamwork condition, they will report higher academic well-being (interest and effort) as compared to the traditional learning condition.

-

H2a. When the students are assigned to the friendly competition condition, they will report higher basic psychological need satisfaction as compared to the traditional learning condition.

-

H2b. When the students are assigned to the friendly competition condition, they will report higher academic well-being (interest and effort) as compared to the traditional learning condition.

-

H3a. When students are assigned to the choice condition of whether to participate or not, they will report higher basic psychological need satisfaction as compared to the traditional learning condition.

-

H3b. When students are assigned to the choice condition of whether to participate or not, they will report higher academic well-being (interest and effort) as compared to the traditional learning condition.

-

H4a. When the students are assigned to the anonymous condition, they will report higher basic psychological need satisfaction compared to the traditional learning condition.

-

H4b. When the students are assigned to the anonymous condition, they will report higher academic well-being (interest and effort) as compared to the traditional learning condition.

-

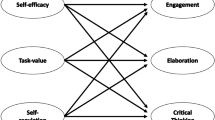

H5. Psychological need satisfaction would mediate the effects of the condition on academic well-being (Fig. 1).

Pilot study

A pilot study compared GET to traditional learning to examine the effects on academic well-being (in terms of interest and effort) in English lessons as a tool. Our initial hypothesis was that GET would promote academic well-being more so than a traditional learning comparison.

Method

Participants

The study involved 30 students studying at a private foreign language institute in an urban area in Greece, 12 boys (40%) and 18 girls (60%) between the ages of 11 and 16 years during the school year 2019–2020, with the consent of their parents. The number of participants involved was determined by the specific classrooms to which we had access in the pilot study collection. All children (100%) had Greek citizenship, and Greek was their native language. Students in this pilot study came from an advantaged socioeconomic background and were technologically literate—they were aware of how to operate the SRS. The teacher (female, aged 50 with university degrees in English Literature and Psychology) who was responsible for both conditions had 25 years of teaching experience in the private sector in a school that had a lot of technology in the classrooms. Specifically, every class had an interactive board and a student response system. The teacher was aware of how to develop a classroom-based intervention.

The English course using GET was attended by four (26.6%) boys and 11 (73.4%) girls, and the traditional English course was attended by eight (53.4%) boys and seven (46.6%) girls. Students were assigned to one of two conditions: The experimental group was taught with the aid of GET, which consisted of a transmitter, a clicker for each student, and a clicker for the teacher. The comparison group was taught through relatively traditional methods of using a whiteboard and a CD player.

Measure instruments

Students responded to the Motivated Strategies of Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ; Pintrich et al., 1991) as it is a measuring instrument designed to assess students’ motivation and the use of learning strategies. The MSLQ includes two areas. The first refers to the social and motivational factors and the second to learning strategies. In this pilot study, a subset of items from the first area was only used to evaluate outcomes of the condition of interest and effort. Specifically, a total of seven items on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 is “strongly disagree,” 2 is “disagree,” 3 is “not sure,” 4 is “agree,” and 5 is “strongly agree” were used to measure academic well-being of interest and effort. Three items of measuring interest were: “I like the subject matter of this course,” “It is important for me to learn the course material in this class,” and “I am very interested in the content of area of this course.” Effort was measured with four items: “If I wanted to change, I am sure I could”; “When I have a goal, I can usually plan how to achieve it”; “I’m good at finding different ways to get what I want”; and “I can achieve goals that I have set for myself.” In this pilot study, Cronbach’s alphas for the interest items were α = 0.82 and for the effort items were α = 0.64.

Condition

The class randomly assigned to the GET condition used the interactive whiteboard consisting of a computer, a projector through which the material of the digital book was projected on the whiteboard, and two speakers. SRS used in the GET condition consists of a transmitter and a clicker for each student and a clicker for the teacher (Fig. 2). A second class, randomly assigned to traditional learning, used the traditional whiteboard and a CD player for their lesson.

Procedure

The experiment took place across a period of 2 months. Students participated in English lessons three times a week for 90 min. At the start of a teaching semester, students reported on demographics and completed the questionnaire. Classes were randomly assigned to either a GET or traditional learning condition. The GET condition employed the interactive whiteboard as a necessary tool for the SRS. The students watched short videos based on the texts and listened to the audio parts. Exercises were also corrected with the help of the interactive whiteboard. The clickers were introduced in the final 20 min of every session. The teacher displayed two sets of 15 questions concerned with grammar and vocabulary. Students had 30 s to answer each question using their clickers. For the last 10 s, a sound was heard from the speakers so that the students could respond in time. At the end, a bar chart with percentages for the correct and incorrect answers was displayed, and the students were informed of their points and the time they took, using a leaderboard and progress bars.

The traditional learning group received identical lessons but through traditional means (i.e., using textbooks, written tests, whiteboard, and CD player). They followed the lesson with the help of the teacher and used the traditional CD player to listen to the audio part of the lesson. The correction of the exercises was done orally.

Both conditions were based on level B1 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001). Consequently, the same syllabus from the same course book, grammar book, workbook, and vocabulary was taught. At the end of the 2 months, students completed the same questionnaire measuring interest and effort.

Data analytic strategy

A repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with time defined as a within-person variable with two levels: baseline and follow-up. Condition was defined as a between-person predictor. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28.0.0 (190). Raw data and analysis code for this study can be sent without undue reservation by emailing the corresponding author.

Results

Sample characteristics

A Shapiro–Wilk test (p > 0.05) (Razali & Wah, 2011; Shapiro & Wilk, 1965) and a visual inspection of their histograms, normal Q-Q plots, and box plots showed that academic well-being was normally distributed with a skewness of 0.157 (SE = 0.427) and a kurtosis of 0.370 (SE = 0.833) for time 1 and a skewness of − 0.427 (SE = 0.427) and a kurtosis of − 0.113 (SE = 0.833) for time 2. Inspecting academic well-being separately as interest and effort were also normally distributed, interest time 1 has a skewness of − 0.787 (SE = 0.427) and a kurtosis of − 0.450 (SE = 0.833), and interest time 2 has a skewness of − 0.119 (SE = 0.427) and a kurtosis of − 1.207 (SE = 0.833). Effort time 1 has a skewness of − 0.074 (SE = 0.427) and a kurtosis of − 0.295 (SE = 0.833), and effort time 2 has a skewness of 0.399 (SE = 0.427) and a kurtosis of 0.422 (SE = 0.833) (Cramer, 1998; Cramer & Howitt, 2004; Doane & Seward, 2011).

Academic well-being results

Analyses showed a significant interaction wherein the students increased in academic well-being as a function of condition (GET or traditional), F(1, 28) = 6.45, p = 0.017, d = 0.96. We proceeded to investigate this interaction by splitting up the two types of education. In the SRS condition, academic well-being increased from baseline to follow-up (t = 2.84, p = 0.013, d = 1.52). In the traditional condition, there was no change from baseline to follow-up (t = 0.54, p = 0.601, d = 0.29) (Fig. 3).

Conclusion

Results of the pilot study showed that academic well-being (students’ interest and effort) increased across time when students used classroom technology but did not change when using traditional learning.

Study 1

The purpose of study 1 was to build on the conceptual model testing academic well-being and to compare different motivational climates for delivering GET. More specifically, we tested motivational framing for gamified experiential learning (GET) by putting students in teams, giving them the choice to participate or not, to be part of a friendly competition, or to participate anonymously. Hence, we investigated the role of GET as an educational tool and its relationship with the development of autonomy, relatedness, and competence of SDT, resulting in greater interest and effort thus academic well-being (Fig. 1). In the pilot study, we had focused on the use of technology (interactive whiteboard and SRS) throughout an academic semester compared to traditional learning without technology to measure the academic well-being indicators of interest and effort. Study 1 built on these findings by using the interactive whiteboard with all classes to isolate only the effect of SRS in the experiment and to measure the outcome of academic well-being mediated by the three basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Method

Participants and design

The study involved 120 students studying in a private foreign language institute in an urban area in Greece, including 65 boys (54.2%) and 55 girls (45.8%) during the school year 2020–2021. Students varied in age from 9 to 16 years old (M = 12.58, SD = 2.4). The number of participants involved was determined by the specific classrooms to which we had access in the study 1 collection. Students in study 1 came from an advantaged socioeconomic background and were technologically literate—they were aware of how to operate the SRS. The teacher who was responsible for both conditions was the same teacher who conducted the pilot study.

Transparency and openness

Because we were testing young children and using a relatively subtle manipulation of GET, we anticipated a small effect size across all measures. Therefore, based on a power analysis anticipating f = 0.20, and setting power at 0.90 for an omnibus effect across groups (which required n = 36), we aimed to recruit n = 40 per age group (9–11 years, 12–14 years, 15–16 years). There were no exclusion criteria set.

The study received ethics approval from the University Research Ethics Committee of the University of Reading (num. 2020–175-NW) and was pre-registered (https://osf.io/phgs3/) prior to data collection, along with the planned design and analytic approach. Raw data and analysis code for this study can be sent without undue reservation by emailing the corresponding author.

An email was sent to the parents of the students with the details of the experiment. Both parent and student consented prior to the start of the experiment. All students took part in four experimental conditions using GET, as well as one comparison condition that used traditional learning to compare the different motivational climates. As such, this study involved a 5-factor within-subject design presented in a random order.

GET conditions involved a clicker for each student and a clicker for the teacher as in the pilot study. The difference in study 1 is that the GET conditions made one of four motivationally relevant framing salient:

-

(1)

Teamwork, in which students were allowed to collaborate in teams of three before clicking on the answer

-

(2)

Friendly competition salient, where the students worked alone and, after answering all the questions in each set, were shown their scores on the leaderboard

-

(3)

Choice, where the students were allowed to choose whether to participate or not

-

(4)

Anonymous, where the students participated without revealing who they were on the leaderboard as only numbers were shown

As a comparison condition, the students also took part in a traditional learning condition where they answered the same set of questions on paper instead of using GET; nevertheless, the condition was matched in terms of the duration of the manipulation, and the general content of learning was identical.

At the end of each procedure, the students answered the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI; Deci & Ryan, 1985) which was delivered through Qualtrics Survey Solutions after the survey was translated into Greek and back-translated (see on https://osf.io/phgs3/). The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24.

Procedure

The experiment was conducted in five lessons. One lesson was used for each condition (teamwork, friendly competition salient, choice, anonymity, and a comparison traditional learning condition). Students in a classroom received the same order of condition, but the order across the five conditions was randomized across classrooms to avoid confounding effects of time. In all conditions (experimental and comparison), the students used the interactive whiteboard to project the textbook as in the pilot study. Students watched short videos based on the texts and listened to the audio parts. Exercises were also corrected with the help of the interactive whiteboard.

In the last 20 min of each lesson, the students were introduced to the condition into which they had been randomly assigned. In the experimental condition, the teacher, with the help of the transmitter and clicker, displayed two sets of 15 questions on the interactive board. The former was related to previously taught grammar, and the latter was related to vocabulary. Students answered within 30 s by using their clickers in groups or individually—depending on the condition. For the last 10 s, a sound was heard from the speakers so that they responded in time. Then, a bar chart with percentages of correct and incorrect answers was displayed, and the students were shown their scores and time on a leaderboard. In the traditional learning condition, instead of being given a clicker, the students were assigned to sit a written test of two sets of 15 multiple-choice questions related to grammar and vocabulary to match the experimental conditions. After each condition, students responded to the questionnaire.

Measure instruments

Academic well-being and psychological need satisfaction

Academic well-being and psychological need satisfaction were both measured with the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI; Deci & Ryan, 1985). This research is relatively new to Greece so we do not have indicators of validity in the Greek sample. However, the surveys were translated and back-translated by researchers, and students were invited to ask for clarification if confused. The IMI was used because its multiple subscales tap at these constructs well and it is suitable for use in academic settings (Raes et al., 2020). Items described below were paired with a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “not at all true” to 4 “somewhat” to 7 “very true.”

Need satisfaction

Perceptions that psychological needs were satisfied were measured through three subscales. Autonomy was measured with seven items including “I believe I had some choice about doing this activity” and “I did this activity because I had no choice” (R)(α = 0.78). Competence included 6 items including “I think I did pretty well at this activity, compared to other students” and “I am satisfied with my performance at this task” (α = 0.90). Relatedness included six items including “I felt close to my classmates” and “I felt really distant to my classmates” (R)(α = 0.81).

Academic well-being

Academic well-being was measured through self-reported interest and effort. Interest included seven items including “I enjoyed doing this activity very much” and “I thought it was a boring activity” (R)(α = 0.69). Effort involved five items including “I put a lot of effort into this” and “I did not put much energy into this” (R)(α = 0.90).

Data analytic strategy

A repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with five within-subject levels: four GET conditions (teamwork, choice, friendly competition, anonymity) and one traditional learning condition. Conditions were defined as a between-person predictor. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28.0.0 (190). Raw data and analysis code for this study can be sent without undue reservation by emailing the corresponding author. Means and standard errors for each condition are summarized in Table 1. Pairwise comparisons of conditions are summarised in Table 2. In addition, pre-registered indirect effects were tested with PROCESS, which allows researchers to identify the combined effects of predictors to mediators and, ultimately, to outcomes controlling for direct effects and multiple mediators (Hayes, 2018). Each of the three motivational conditions that showed increased need satisfaction was tested against two comparison conditions: traditional learning and anonymous GET. The three mediators were defined separately in models, to test each of their independent effects. Student-reported interest and effort were tested as two separate outcomes. Findings of these models are summarized in Table 3.

Results

Sample characteristics

A Shapiro–Wilk test (p > 0.05) (Razali & Wah, 2011; Shapiro & Wilk, 1965) and a visual inspection of their histograms, normal Q-Q plots, and box plots showed that the outcomes were normally distributed for both males and females, with a skewness of − 0.587 (SE = 0.299) and a kurtosis of 0.123 (SE = 0.590) for the males and a skewness of − 0.554 (SE = 0.319) and a kurtosis of − 0.205 (SE = 0.628) for the females (Cramer, 1998; Cramer & Howitt, 2004; Doane & Seward, 2011).

Basic psychological needs

Condition predicted autonomy need satisfaction, F(4, 468) = 217.74, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.65. Post hoc comparisons are presented in Table 2. The choice condition predicted the greatest self-reported autonomy (M = 6.28, all ps < 0.001), followed by friendly competition (M = 4.72, p < 0.001) and teamwork (M = 4.67, p < 0.001) conditions, which were not significantly different from one another. Participants in the anonymous condition reported feeling slightly less autonomous (M = 4.05, p < 0.001), followed by even less autonomy in the traditional condition (M = 3.05, p < 0.001).

Condition predicted competence, F(4, 468) = 26.47, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.18 (Table 2). The teamwork condition predicted the greatest self-reported competence (M = 6.20, all ps < 0.001), followed by choice condition (M = 6.05, vs. friendly competition, anonymous, and traditional: ps < 0.01). Participants in the friendly competition condition reported feeling more competent (M = 5.43, p < 0.001) than those in the traditional (M = 5.36, p < 0.001) and anonymous (M = 5.28, p < 0.001) conditions. There was no significant difference between the anonymous and traditional conditions predicting competence (p = 0.14).

Condition predicted relatedness, F(4, 468) = 62.24, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.35, see Table 2 for post hoc comparisons. The teamwork condition predicted the greatest self-reported relatedness (M = 6.38, all ps < 0.001), followed by the choice condition (M = 6.11, vs. friendly competition, anonymous, and traditional: ps < 0.01). Participants in the friendly competition condition reported feeling more relatedness (M = 5.87, p < 0.001) than those in the anonymous (M = 5.46, p < 0.001) and traditional (M = 5.34, p < 0.001) conditions. There was no difference between the anonymous and traditional conditions predicting relatedness (p = 0.14).

Academic well-being

Condition predicted interest, F(4, 468) = 150.06, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.56. Post hoc comparisons are presented in Table 2. The teamwork condition (M = 6.48, all ps < 0.001), and the choice condition (M = 6.38, vs. friendly competition, anonymous, and traditional: ps < 0.01), predicted the greatest self-reported interest. Participants in the friendly competition condition reported feeling more interested (M = 6.03, p < 0.001) than those in the anonymous (M = 4.73, p < 0.001) and traditional (M = 4.26, p < 0.001) conditions.

Condition predicted perceived effort, F(4, 468) = 59.92, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.34. The choice condition predicted the greatest self-reported effort (M = 5.92, all p < 0.001), followed by the teamwork condition (M = 5.89, all p < 0.001). Participants in the traditional and friendly competition conditions reported making a similar effort M = 5.61, p < 0.001 and M = 5.59, p < 0.001, respectively. Participants in the anonymous condition self-reported the least effort (M = 4.25, p < 0.001 as compared to other conditions). Analyses are presented in Table 2.

Indirect analyses

Predicting interest

A first set of three models defined students’ self-reported interest as the outcome variable. Results of models testing which of the three need satisfactions would mediate the effects of the teamwork and choice conditions contrasted against our two comparison conditions showed similar results. Namely, all three psychological needs (autonomy, relatedness, and competence) mediated the effect of the teamwork and choice conditions on greater interest in comparison to the traditional learning condition. (Teamwork: relatedness satisfaction, b = 0.12, se = 0.04, 95% CI [0.05, 0.20]; competence satisfaction, b = 0.39, se = 0.06, 95% CI [0.27, 0.51]; and autonomy satisfaction, b = 0.34, se = 0.05, 95% CI [0.24, 0.45]; choice: relatedness satisfaction, b = 0.09, se = 0.03, 95% CI [0.03, 0.14]; competence satisfaction, b = 0.31, se = 0.07, 95% CI [0.18, 0.45]; and autonomy satisfaction, b = 0.82, se = 0.10, 95% CI [0.64, 1.03].)

Autonomy and relatedness need satisfactions, but not competence need satisfaction, mediated the effect of the competition (versus traditional learning) condition on greater interest (relatedness satisfaction, b = 0.06, se = 0.02, 95% CI [0.02, 0.10]; autonomy satisfaction, b = 0.35, se = 0.06, 95% CI [0.25, 0.47]).

Predicting effort

The effects of teamwork and choice on effort were driven by indirect effect through competence satisfaction only, (teamwork: competence satisfaction, b = 0.44, se = 0.07, 95% CI [0.30, 0.58]; relatedness satisfaction, b = 0.08, se = 0.07, 95% CI [− 0.06, 0.21]; and autonomy satisfaction, b = − 0.09, se = 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.20, 0.02]; choice: competence satisfaction, b = 0.35, se = 0.08, 95% CI [0.21, 0.51]; relatedness satisfaction, b = 0.06, se = 0.05, 95% CI [− 0.05, 0.15]; and autonomy satisfaction, b = − 0.09, se = 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.20, 0.02]). The effect of competition salient on effort was not driven by indirect effect through any of the need satisfactions: competence satisfaction, b = 0.04, se = 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.08, 0.17]; relatedness satisfaction, b = 0.04, se = 0.03, 95% CI [− 0.03, 0.10]; and autonomy satisfaction, b = − 0.09, se = 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.21, 0.02].

Discussion

The current research was designed to test the effects of gamified experiential technology (GET) on academic well-being and explore whether positive motivational framing could further enhance any effects. Findings of the pilot and full study 1 suggested that when using GET in the classroom, students experienced more academic well-being compared to traditional learning. Study 1 conceptually replicated the findings of the pilot study that GET use leads to more positive student outcomes than traditional learning. Furthermore, in this study, we observed that need satisfaction largely explains the relations between GET use and the academic well-being outcomes of interest and effort, and we also saw that building motivational framing strategies such as assigning students to use SRS in teams, using a friendly competition climate and helping students feel that they have a choice to participate or not, could further enhance GET use benefits. Notably, despite being given a choice, no students in the study opted out of the activity, suggesting that perhaps the activity itself motivated engagement.

Although we anticipated that each motivational framing strategy would elicit a corresponding psychological need (i.e., learning as a team would foster relatedness, friendly competition would foster competence, and choice would foster autonomy), results did not support these “clean” relationships between strategies used by teachers during interactive learning and specific corresponding needs. Instead, each of these three motivational strategies was found to broadly support psychological need satisfaction across needs. When students received GET as a team, they felt a sense of relatedness with others, a sense of competence, and a sense of having a choice in what they did, and psychological need satisfaction helped, in part, to explain how learning as a team fostered their interest in the learning task. When students were given the choice whether to participate or not or when they were encouraged to engage in friendly competition with classmates, they felt more autonomy in relation to the task and more relatedness with their classmates and, for these reasons, reported greater interest in the task. In addition, while they were working in a team and given the choice to participate, they felt competent which in turn led to greater effort in GET. Both teamwork and choice motivational framing strategies also supported a sense of competence need satisfaction, which in turn led to greater effort and interest in the activity.

By comparison, when GET was implemented anonymously and without these supportive motivational framings, students reported lower autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and as a result, their interest and effort in the task were relatively low and comparable to those of traditional learning.

Implications

Overall, the use of gamified experiential technology (GET) produced better learning outcomes than traditional learning. The results of our study expand previous research showing that learning conditions that support relatedness, competence, and autonomy needs enhance students’ academic well-being (i.e., students’ interest in the task and the effort they put into it; David & Weinstein, 2023; Nikou & Economides, 2016). Condition effects are also in line with studies identifying the benefits of positive motivational framing strategies on learning outcomes, both directly and indirectly through supporting these basic psychological needs. In our findings, students felt more related to one another when GET use was implemented through teamwork and friendly competition and when they received a choice.

Teamwork not only enhanced relatedness, but also supported competence and autonomy needs—suggesting more global benefits for students learning together with classmates. The sense of relatedness, in turn, led to more interest, building on previous work that academic well-being is enhanced when the students feel secure working with peers (Francisco-Aparicio et al., 2013; Shadiev & Yang, 2020).

Friendly competition supported competence, conceptually replicating a previous experiment that concluded that leaderboard points enhance competence (Bai et al., 2021), and research shows that friendly competition stimulates high interest by providing informational feedback and positive challenge (Lehman et al., 2012).

Interestingly, providing students choice on engaging in the activity (all students chose to participate in the experiment) supported all three basic needs and, like previous research (Patall et al., 2008, 2010), was associated with more interest and effort. This finding suggested that gamified learning is most beneficial when students can decide on their actions following their interests and values (Deci & Ryan, 2012). It corresponds with the Montessori method, which promotes choice and autonomy to increase high intrinsic motivation and positive learning outcome (Montessori et al., 2017; Rathunde & Csikszentmihalyi, 2005).

In all, the results suggest that educators who have the aim of inspiring intrinsic motivation within a learning environment could benefit by incorporating interactive technologies into their education (pilot study and study 1) and, moreover, that they should carefully consider how they frame technology use in terms of instructional strategies. Here, we observed that multiple motivational strategies can be used by teachers to increase need satisfaction and improve the interest and effort of students. But others likely exist that were not tested here, and we recommend that along with additional research designed to explore these, educators can consider how they, personally, prefer to enrich learning with fun or playful approaches that engage students in active learning.

Although the pilot study tracked the basic effects of GET use across time, study 1 was a within-subject experimental design that examined only immediate responses to motivational framing strategies (employing teamwork, friendly competition, and choice). As such, future research building on these experiments can integrate the pilot and study 1 methodological approaches to test cumulative and long-term effects of positive motivational framing strategies and need satisfaction in gamified learning contexts. There is reason to believe that students exposed to supportive motivational framing strategies would engage in more learning over time, since repeating interesting tasks builds interest over time (Krapp, 2002; Silvia, 2001). Repeated quizzes with the use of gamification may therefore result in a lasting interest (Topîrceanu, 2017). The gamification literature, more broadly, would benefit from such an approach, since most of the previous experiments last just one or very few sessions (Boudadi & Gutiérrez-Colón, 2020; Sun & Hsieh, 2018). This study conceptualized basic psychological need satisfaction as a spectrum from neutral to positive, but SDT recognizes the difference between need satisfaction and need frustration, each with specific implications for well-being and behavioral outcomes (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). Additional research by Burgueño et al. (2023) has similarly shown that both satisfaction and frustration are relevant for predicting learning and well-being outcomes in education. We suggest that future research define both for a better understanding of experiential and motivational predictors of need experiences.

Limitations

In the pilot study, the GET condition was different from the comparison condition; the students not only used SRS but also the interactive whiteboard that is a necessary tool for the SRS. Therefore, we could not isolate only the effect of SRS in the experiment. Having this in mind, we used the interactive board and digital book in study 1 in all lessons before introducing the conditions.

It is also worth noting that study 1 was conducted immediately after the reopening of school and after a 6-month period of online lessons during the COVID-19 lockdown. The timing may have affected the results positively across all conditions, since the students were happier and felt refreshed returning to the classroom. It may have been that additional enthusiasm enhanced the effects of GET on student outcomes. In this case, GET may be considered a positive education approach to help children combat distress or disinterest (Waters et al., 2021), but more research is needed to examine its effects across life circumstances.

To expand on the current work, GET use needs to be tested alongside observational or behavioral data, which can be used to triangulate and to seek convergent with self-reported student responses as we used in these studies. Future work taking this approach can provide more robust evidence about the use of GET in relation to learning outcomes. Adding to this, we should also mention that there was no external assessment to ensure the fidelity of the pedagogical model in question in either study (Hastie & Casey, 2014) which should also be considered in the future.

Finally, we recognize that the reliability was lower in some measurements than some recommend (Viladrich et al., 2017) (in particular, effort in the pilot study had α = 0.64, and interest in study 1 had α = 0.69), but interpreting these findings, understandably, some see α = 0.60 as an acceptable benchmark (Cohen et al., 2011). We should consider in future experiments that effects might be different, and possibly more robust, when using more reliable measures.

Conclusion

The current research has provided a number of notable insights into the acquisition of English grammar and vocabulary by means of gamified experiential technology (GET) use to enhance student academic well-being. Two in-class experiments showed that implementing GET significantly enhances the learning environment. Furthermore, students are all the more interested and willing to put some effort into the lesson when GET use is delivered in supportive motivational framing strategies that satisfy basic psychological needs. Taking it all together, technology use can enhance classroom experiences and even more so when students experience choice, feel related to peers, and are encouraged to feel effective at the tasks they undertake.

Data availability

Raw data and analysis code for this study can be sent without undue reservation by emailing the corresponding author.

References

Akram, H., & Abdelrady, A. H. (2023). Application of ClassPoint tool in reducing EFL learners’ test anxiety: An empirical evidence from Saudi Arabia. Journal of Computers in Education, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-023-00265-z

Álvarez, C., Baloian, N., Zurita, G., & Guarini, F. (2017). Promoting active learning in large classrooms: Going beyond the clicker. Collaboration and Technology: 23rd International Conference, CRIWG 2017, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, August 9–11, 2017, Proceedings 23 (pp. 95–103). Springer International Publishing.

Anderson, M. (2016). Learning to choose, choosing to learn: The key to student motivation and achievement. ASCD.

Bai, B., & Wang, J. (2023). The role of growth mindset, self-efficacy and intrinsic value in self-regulated learning and English language learning achievements. Language Teaching Research, 27(1), 207–228.

Bai, S., Hew, K. F., Sailer, M., & Jia, C. (2021). From top to bottom: How positions on different types of leaderboard may affect fully online student learning performance, intrinsic motivation, and course engagement. Computers & Education, 173, 104297.

Benson, J. D., Szucs, K. A., Deiuliis, E. D., & Leri, A. (2017). Impact of student response systems on initial learning and retention of course content in health sciences students. Journal of Allied Health, 46(3), 158–163.

Bitrián, P., Buil, I., & Catalán, S. (2021). Enhancing user engagement: The role of gamification in mobile apps. Journal of Business Research, 132, 170–185.

Boudadi, N. A., & Gutiérrez-Colón, M. (2020). Effect of gamification on students’ motivation and learning achievement in second language acquisition within higher education: A literature review 2011–2019. The EuroCALL Review, 28(1), 57–69.

Burgueño, R., García-González, L., Abós, Á., & Sevil-Serrano, J. (2023). Students’ need satisfaction and frustration profiles: Differences in outcomes in physical education and physical activity-related variables. European Physical Education Review, 1356336X231165229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X231165229

Caldwell, J. E. (2007). Clickers in the large classroom: Current research and best-practice tips. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 6(1), 9–20.

Çelik, S., & Baran, E. (2022). Student response system: Its impact on EFL students’ vocabulary achievement. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 31(2), 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2021.1986125

Christy, K. R., & Fox, J. (2014). Leaderboards in a virtual classroom: A test of stereotype threat and social comparison explanations for women’s math performance. Computers & Education, 78, 66–77.

Cohen, T. R., Wolf, S. T., Panter, A. T., & Insko, C. A. (2011). Introducing the GASP scale: A new measure of guilt and shame proneness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 947–966. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022641

Council of Europe.Council for cultural co-operation.Education Committee. Modern Languages Division. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge University Press.

Cramer, D. (1998). Fundamental statistics for social research: Step-by-step calculations and computer techniques using SPSS for Windows. Psychology Press.

Cramer, D., & Howitt, D. L. (2004). The sage dictionary of statistics: A practical resource for students in the social sciences. Sage.

David, L., & Weinstein, N. (2023). A gamified experiential learning intervention for engaging students through satisfying needs. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 00472395231174614. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472395231174

Davis, K., & Singh, S. (2015). Digital badges in afterschool learning: Documenting the perspectives and experiences of students and educators. Computers & Education, 88, 72–83.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. The Oxford handbook of human motivation, 18(6), 85–107.

Deci, E. L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2004). Self-determination theory and basic need satisfaction: Understanding human development in positive psychology. Ricerche di psicologia, 27(1), 23–40.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum Publishing Co.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2016). Optimizing students’ motivation in the era of testing and pressure: A self-determination theory perspective. Building autonomous learners (pp. 9–29). Springer, Singapore.

Doane, D. P., & Seward, L. E. (2011). Measuring skewness: A forgotten statistic?. Journal of statistics education, 19(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/10691898.2011.11889611

Dohn, N. B., Fago, A., Overgaard, J., Madsen, P. T., & Malte, H. (2016). Students’ motivation toward laboratory work in physiology teaching. Advances in Physiology Education, 40(3), 313–318.

Dunlosky, J., Badali, S., Rivers, M. L., & Rawson, K. A. (2020). The role of effort in understanding educational achievement: Objective effort as an explanatory construct versus effort as a student perception. Educational Psychology Review, 32, 1163–1175.

Fang, J., Zhao, Z., Wen, C., & Wang, R. (2017). Design and performance attributes driving mobile travel application engagement. International Journal of Information Management, 37(4), 269–283.

Fernández, N. G., & Jácome, G. A. C. (2016). ¿ Cómo aplicar la" flipped classroom" en primaria? Una guía práctica. Aula De Innovación Educativa, 250, 46–50.

Fithriani, R. (2021). The utilization of mobile-assisted gamification for vocabulary learning: Its efficacy and perceived benefits. Computer Assisted Language Learning Electronic Journal (CALL-EJ), 22(3), 146–163.

Francisco-Aparicio, A., Gutiérrez-Vela, F. L., Isla-Montes, J. L., & Sanchez, J. L. G. (2013). Gamification: Analysis and application. In: Penichet, V., Peñalver, A., Gallud, J. (Eds.) New Trends in Interaction, Virtual Reality and Modeling. Human–Computer Interaction Series. Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-5445-7_9

Groening, C., & Binnewies, C. (2019). “Achievement unlocked!”-the impact of digital achievements as a gamification element on motivation and performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 151–166.

Groh, F. (2012). Gamification: State of the art definition and utilization. Institute of Media Informatics Ulm University, 39, 31.

Hastie, P. A., & Casey, A. (2014). Fidelity in models-based practice research in sport pedagogy: A guide for future investigations. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 33(3), 422–431.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40.

Ho, M. H. W., & Chung, H. F. (2020). Customer engagement, customer equity and repurchase intention in mobile apps. Journal of Business Research, 121, 13–21.

Huang, B., & Hew, K. F. (2021). Using gamification to design courses. Educational Technology & Society, 24(1), 44–63.

Kaimara, P., Poulimenou, S. M., Oikonomou, A., Deliyannis, I., & Plerou, A. (2019). Smartphones at schools? Yes, why not? European Journal of Engineering and Technology Research, 2019, 1–6.

Kam, A. H., & Umar, I. N. (2018). Fostering authentic learning motivations through gamification: A self-determination theory (SDT) approach. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology, 13, 1–9.

Kasurinen, J., & Knutas, A. (2018). Publication trends in gamification: A systematic mapping study. Computer Science Review, 27, 33–44.

Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 191–210.

Krapp, A. (2002). Structural and dynamic aspects of interest development: Theoretical considerations from an ontogenetic perspective. Learning and Instruction, 12(4), 383–409.

Landers, R. N., & Landers, A. K. (2014). An empirical test of the theory of gamified learning: The effect of leaderboards on time-on-task and academic performance. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 769–785.

Landers, R. N., Bauer, K. N., & Callan, R. C. (2017). Gamification of task performance with leaderboards: A goal setting experiment. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 508–515.

Lehman, B., D’Mello, S., & Graesser, A. (2012). Confusion and complex learning during interactions with computer learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education, 15(3), 184–194.

Lei, S. A. (2010). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: Evaluating benefits and drawbacks from college instructors’ perspectives. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 37(2), 153–161.

Leo, F. M., Mouratidis, A., Pulido, J. J., López-Gajardo, M. A., & Sánchez-Oliva, D. (2022). Perceived teachers’ behavior and students’ engagement in physical education: The mediating role of basic psychological needs and self-determined motivation. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 27(1), 59–76.

Li, X., & Chu, S. K. W. (2021). Exploring the effects of gamification pedagogy on children’s reading: A mixed-method study on academic performance, reading-related mentality and behaviors, and sustainability. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(1), 160–178.

Liu, C. L., & Lai, C. L. (2023). An exploration of instructional behaviors of a teacher in a mobile learning context. Teaching and Teacher Education, 121, 103954.

Liu, C., Sands-Meyer, S., & Audran, J. (2019). The effectiveness of the student response system (SRS) in English grammar learning in a flipped English as a foreign language (EFL) class. Interactive Learning Environments, 27(8), 1178–1191.

Malone, T. W., & Lepper, M. R. (2021). Making learning fun: A taxonomy of intrinsic motivations for learning. Aptitude, learning, and instruction (pp. 223–254). Routledge.

Mee Mee, R. W., Shahdan, T. S. T., Ismail, M. R., Ghani, K. A., Pek, L. S., Von, W. Y., ... & Rao, Y. S. (2020). Role of gamification in classroom teaching: Pre-service teachers' view. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 9(3), 684–690. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v9i3.20622

Miller, W. (2012). iTeaching and learning: Collegiate instruction incorporating mobile tablets. Library Technology Reports., 48(8), 54–59.

Montazami, A., Pearson, H. A., Dube, A. K., Kacmaz, G., Wen, R., & Alam, S. S. (2022). Why this app? How educators choose a good educational app. Computers & Education, 184, 104513.

Montessori, M., Hunt, J. M., & Valsiner, J. (2017). The montessori method. Routledge.

Moore, R. L., Blackmon, S. J., & Markham, J. (2018). Making the connection: Using mobile devices and Poll Everywhere for experiential learning for adult students. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 29(3), 397–421.

Na, K., & Han, K. (2023). How leaderboard positions shape our motivation: The impact of competence satisfaction and competence frustration on motivation in a gamified crowdsourcing task. Internet Research, 33(7), 1–18.

Nikou, S. A., & Economides, A. A. (2016). The impact of paper-based, computer-based and mobile-based self-assessment on students’ science motivation and achievement. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 1241–1248.

O’Brien, C. (2016). Education for sustainable happiness and well-being. Routledge.

Parong, J., & Mayer, R. E. (2018). Learning science in immersive virtual reality. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(6), 785.

Parra-González, M. E., López Belmonte, J., Segura-Robles, A., & Fuentes Cabrera, A. (2020). Active and emerging methodologies for ubiquitous education: Potentials of flipped learning and gamification. Sustainability, 12(2), 602.

Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., & Robinson, J. C. (2008). The effects of choice on intrinsic motivation and related outcomes: A meta-analysis of research findings. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 270.

Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., & Wynn, S. R. (2010). The effectiveness and relative importance of choice in the classroom. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 896.

Pearson, R. J. (2017). Tailoring clicker technology to problem-based learning: What’s the best approach? Journal of Chemical Education, 94(12), 1866–1872.

Peng, W., Lin, J. H., Pfeiffer, K. A., & Winn, B. (2012). Need satisfaction supportive game features as motivational determinants: An experimental study of a self-determination theory guided exergame. Media Psychology, 15(2), 175–196.

Perez-Manzano, A., & Almela-Baeza, J. (2018). Gamification and transmedia for scientific promotion and for encouraging scientific careers in adolescents. Comunicar. Media Education Research Journal, 26(55), 93–103.

Peter, A., Salimun, C., & Seman, E. A. A. (2019). The effect of individual gamification elements in intrinsic motivation and performance. Asian Journal of Research in Education and Social Sciences, 1(1), 48–61.

Pettit, R. K., McCoy, L., Kinney, M., & Schwartz, F. N. (2015). Student perceptions of gamified audience response system interactions in large group lectures and via lecture capture technology. BMC Medical Education, 15, 1–15.

Piaget, J. (2013). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood. Routledge.

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A.F., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1991). A manual for the use of motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ), Eric: Michigan. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED338122.pdf

Qiao, S., Yeung, S. S. S., Zainuddin, Z., Ng, D. T. K., & Chu, S. K. W. (2023). Examining the effects of mixed and non-digital gamification on students’ learning performance, cognitive engagement and course satisfaction. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(1), 394–413.

Raes, A., Vanneste, P., Pieters, M., Windey, I., Van Den Noortgate, W., & Depaepe, F. (2020). Learning and instruction in the hybrid virtual classroom: An investigation of students’ engagement and the effect of quizzes. Computers & Education, 143, 103682.

Rathunde, K., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2005). Middle school students’ motivation and quality of experience: A comparison of Montessori and traditional school environments. American Journal of Education, 111(3), 341–371.

Razali, N. M., & Wah, Y. B. (2011). Power comparisons of Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson-Darling tests. Journal of Statistical Modeling and Analytics, 2(1), 21–33.

Reichert, M., & Mouza, C. (2018). Teacher practices during Y ear 4 of a one-to-one mobile learning initiative. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34(6), 762–774.

Rigby, S., & Ryan, R. M. (2011). Glued to games: How video games draw us in and hold us spellbound: How video games draw us in and hold us spellbound. AbC-CLIo.

Rissanen, A., Hoang, J. G., & Spila, M. (2023). First-year interdisciplinary science experience enhances science belongingness and scientific literacy skills. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. Handbook of Self-Determination Research, 2, 3–33.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860.

Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., Vansteenkiste, M., & Soenens, B. (2021). Building a science of motivated persons: Self-determination theory’s empirical approach to human experience and the regulation of behavior. Motivation Science, 7(2), 97.

Sailer, M., Hense, J. U., Mayr, S. K., & Mandl, H. (2017). How gamification motivates: An experimental study of the effects of specific game design elements on psychological need satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 371–380.

Seaborn, K., & Fels, D. (2015). Gamification in theory and action: A survey. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 74, 14–31.

Shadiev, R., & Yang, M. (2020). Review of studies on technology-enhanced language learning and teaching. Sustainability, 12(2), 524.

Shapiro, S. S., & Wilk, M. B. (1965). An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika, 52(3/4), 591–611.

Silvia, P. J. (2001). Interest and interests: The psychology of constructive capriciousness. Review of General Psychology, 5(3), 270–290.

Smith, K., & Abrams, S. S. (2019). Gamification and accessibility. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 36(2), 104–123.

Statista. (2023). Number of smartphone mobile network subscriptions worldwide from 2016 to 2022, with forecasts from 2023 to 2028, Retrieved March, 2023 from Statista.com: https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-ofsmartphone-users-worldwide/

Stroet, K., Opdenakker, M. C., & Minnaert, A. (2013). Effects of need supportive teaching on early adolescents’ motivation and engagement: A review of the literature. Educational Research Review, 9, 65–87.

Su, Y. L., & Reeve, J. (2011). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intervention programs designed to support autonomy. Educational Psychology Review, 23(1), 159–188.

Sun, J. C. Y., & Hsieh, P. H. (2018). Application of a gamified interactive response system to enhance the intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, student engagement, and attention of English learners. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 21(3), 104–116.

Topîrceanu, A. (2017). Gamified learning: A role-playing approach to increase student in-class motivation. Procedia Computer Science, 112, 41–50.

Triantafyllakos, G., Palaigeorgiou, G., & Tsoukalas, I. A. (2011). Designing educational software with students through collaborative design games: The We! Design&play Framework. Computers & Education, 56(1), 227–242.

Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23(3), 263.

Vansteenkiste, M., Williams, G. C., & Resnicow, K. (2012). Toward systematic integration between self-determination theory and motivational interviewing as examples of top-down and bottom-up intervention development: Autonomy or volition as a fundamental theoretical principle. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(1), 1–11.

Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44, 1–31.

Vansteenkiste, M., Niemiec, C. P., & Soenens, B. (2010). The development of the five mini-theories of self-determination theory: An historical overview, emerging trends, and future directions. The decade ahead: Theoretical perspectives on motivation and achievement, 105–165.

Vasconcellos, D., Parker, P. D., Hilland, T., Cinelli, R., Owen, K. B., Kapsal, N., Lee, J., Antczak, D., Ntoumanis, N., Ryan, R. M., & Lonsdale, C. (2020). Self-Determination theory applied to physical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(7), 1444–1469.

Viladrich, C., Angulo-Brunet, A., & Doval, E. (2017). A journey around alpha and omega to estimate internal consistency reliability. Annals of Psychology, 33(3), 755–782.

Waters, L., Allen, K. A., & Arslan, G. (2021). Stress-related growth in adolescents returning to school after COVID-19 school closure. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 643443.

Werbach, K., & Hunter, D. (2012). For the win: How game thinking can revolutionize your business. Wharton digital press.

Xi, N., & Hamari, J. (2019). Does gamification satisfy needs? A study on the relationship between gamification features and intrinsic need satisfaction. International Journal of Information Management, 46, 210–221.

Young, K. (2016). Teachers’ attitudes to using iPads or tablet computers; implications for developing new skills, pedagogies and school-provided support. TechTrends, 60, 183–189.

Zainuddin, Z., Chu, S. K. W., Shujahat, M., & Perera, C. J. (2020). The impact of gamification on learning and instruction: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Educational Research Review, 30, 100326.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study received Ethics approval from the University Research Ethics Committee of the University of Reading (num. 2020–175-NW) and was pre-registered (https://osf.io/phgs3/) prior to data collection, along with planned design and analytic approach.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Loukia David. Department of Psychology, University of Reading, 7A Ptochokomeiou, Kozani, 50132, Greece. E-mails: loukia.david@pgr.reading.ac.uk, loukiadavid@hotmail.com.

Netta Weinstein. Department of Psychology, Psychology and Clinical Language Science, University of Reading, Earley Gate, Whiteknights, Reading, RG6 6AL, UK. E-mail: N.Weinstein@reading.ac.uk.

Most relevant publication

David, L., & Weinstein, N. (2023). A Gamified Experiential Learning Intervention for Engaging Students Through Satisfying Needs. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 00472395231174614.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

David, L., Weinstein, N. Using technology to make learning fun: technology use is best made fun and challenging to optimize intrinsic motivation and engagement. Eur J Psychol Educ 39, 1441–1463 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00734-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00734-0