Abstract

While interest pursuits are widely recognized as being inherently contextual, what this contextuality entails for different interests has not been explored systematically. In this study, 410 adolescents reported on the temporal, epistemic, material, geographical, social, institutional, and cultural dimensions of 820 interest pursuits. Latent class analyses identified four interest pursuit configurations, revealing quantitative (overall high/low structure) and qualitative (expertise- and social-oriented) differences. We observed similar interests being pursued in the same configuration, but also identified individual differences, reflecting the social–historical meaning and object characteristics of interests, as well as adolescents’ preferences and structural opportunities. The findings show that interest entails more than a preference for an object, but also a preference for a wider configuration, which should be considered when designing (educational) contexts to stimulate adolescents’ interest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Interest is considered a powerful construct that enhances learning, with interest simultaneously occurring with positive feelings, higher valuing, and knowledge development (Hidi & Renninger, 2006; Hofer, 2010). It has been increasingly recognized that pursuing interest is inherently contextual (DiGiacomo et al., 2018; Harackiewicz et al., 2016). Contextuality of what is referred to as “situational” interests (Hidi & Renninger, 2006) is widely acknowledged and studied (e.g., Rotgans & Schmidt, 2011; Skalstad & Munkebye, 2022). Different case studies focusing on adolescents’ interest pursuits illustrated how more sustained interests (sometimes referred to as “individual” interests; Hidi and Renninger (2006)) can also be tied to specific locations and materials (e.g., Azevedo, 2011; Crowley et al., 2015), how specific language, skills, and rules facilitated interest pursuits (e.g., Hollett, 2019; Ito et al., 2019), and/or how other individuals and institutions are involved (e.g., Azevedo, 2013; Gee & Hayes, 2010; Crowley and Jacobs, 2003). These studies suggest large differences when adolescents pursue sustained interest in daily life, even when pursuing seemingly similar objects of interest (Barron, 2006).

Although highly informative, these case descriptions all have a slightly different focus: on locations, materials (Azevedo, 2011, 2013), interaction with social others (Gee & Hayes, 2010; Ito et al., 2019), or institutions (Crowley and Jacobs, 2003), while arguably the combination of different contextual dimensions (i.e., more or less explicitly structured by temporal, epistemic, material, geographical, social, institutional, and cultural aspects) is indicative of differences in interest pursuits (Akkerman & Bakker, 2019). Additionally, because of their explorative nature, studies vary widely, making synthesizing their findings challenging, and raising the question if these cases of interest pursuits are representative of all possible interests. Through the lens of the seven dimensions that we understand as indicative of differences in interest pursuits, we look systematically at differences in pursuits, at a given moment in time and on a larger scale for a wide variety of interests. While the contextuality of situational interests is acknowledged (Renninger, 2000, 2009), large-scale, person-centered analyses from the perspective of adolescents will help conceptualize how pursuing a more sustained interest is also inherently contextual. Understanding the contextuality of a sustained interest will help unfold the complexity of what pursuing that interest entails for individual adolescents. Such a holistic understanding of interests could lead to identifying structural opportunities and inequities within daily life that relate to adolescents pursuing sustained interests. This seems like a necessary and logical first step when thinking about possibilities, chances, obstacles, or impossibilities for parents, teachers, or schools to nurture sustained interests of adolescents (Hidi & Renninger, 2019; Renninger & Hidi, 2020).

Interest pursuits in daily life

Interest is defined as preference for a specific object, be it a material object, topic, idea, activity, or event (Akkerman & Bakker, 2019; Krapp, 2002) that integrates cognition, motivation, and affect (e.g., Hidi & Renninger, 2006; Schiefele & Rheinberg, 1997). As a relational construct, interests are person and context(s) specific (Akkerman & Bakker, 2019), and while pursuing interest over time, adolescents develop a person-specific interest pursuit (e.g., Deci, 1992; Prenzel, 1992). Azevedo (2011, 2013) coined the term “lines of practice” to describe the places and spaces of adolescents’ interest pursuits. Although not static nor predefined (Ito et al., 2019), sustained interest pursuits take on identifiable structures within adolescents’ lives (e.g., Gee & Hayes, 2010). Understanding interests requires uncovering the relevant opportunities and adolescents’ preferences in pursuing their interests (Azevedo, 2011).

Akkerman and Bakker (2019) coined seven dimensions to systematically identify differences in interest pursuits: the temporal, epistemic, material, geographical, social, institutional, and cultural dimensions of interest pursuits. Building on the case studies, we first elaborate on how these dimensions can structure interest pursuits of adolescents in different ways before describing how these dimensions combined result in essentially different interest pursuits.

Temporal

The temporal dimension indicates the moments and rhythm of pursuing an interest. For example, Azevedo (2013) described how the interest pursuit of amateur astronomers is structured by the rhythm of the cosmos, as celestial bodies are observable at night. Temporal structures are also at play when visiting a museum to pursue one’s interest, structured by the opening hours and not being expected at school or work, resulting in daytime visits during the weekend or holidays (Crowley and Jacobs, 2003). There are also reports of interest pursuits limitedly structured temporally, for example, when adolescents pursued their technology interest throughout the day whenever opportunities presented themselves (Barron, 2006).

Epistemic

The epistemic dimension indicates the knowledge and skills related to adolescents pursuing an interest. Gee and Hayes (2010) described how specific skills and knowledge structure interest when being an influential developer within The Sims game (pp. 84–86). Comparable are the unique skills and knowledge about model rocketry used for setting up and launching rockets (Azevedo, 2011). Research identified interest pursuits in which adolescents indicate having little knowledge and skills relating to their interests (Draijer et al., 2020). Skills and knowledge can also be the intended outcome of a pursuit, for example, during interest-related museum visits (Crowley and Jacobs, 2003).

Material

Within the material dimension, pursuing interest is structured by used materials. An interest pursuit for a computer game developer is structured by access to specific programs (Gee & Hayes, 2010). Similarly indicative is the inherent observational equipment of amateur astronomers (Azevedo, 2013) and launching equipment of model rocketeers (Azevedo, 2011). Besides materials that are seemingly specific for certain interests, more everyday materials, such as television when relaxing or mobile phones when listening to music, are indicative for adolescents’ interests (Slot et al., 2020). Some interest pursuits require limited or no materials, for example, when pursuing an interest in religion or thinking about human relationships (Akkerman & Bakker, 2019).

Geographic

Central within the geographical dimension are (online) locations where adolescents pursue their interest. Locations can be interest specific, for instance a particular museum (Crowley and Jacobs, 2003) and specific sites outside the city where artificial lighting is minimal (Azevedo, 2013). Compared to a museum, such a site seems to be less specifically designed for an interest but structures interest pursuit in a similar way. In contrast, Barron (2006) portrays the technology interests of adolescents which are pursued over multiple locations, including some which are not tied to any place at all.

Social

The social dimension indicates whether the pursuing interest is structured by involvement of other individuals. Ito et al. (2019) described how the online involvement of other individuals is essential when pursuing an interest in knitting within the Harry Potter universe (pp. 146–152). On the other hand, Slot and colleagues (2019) revealed how 34% of the total 671 moments adolescents reported to experience interest were alone, not structured by the involvement of others.

Institutional

The institutional dimension indicates whether the interest pursuit is structured by societal institutions, such as museums (Crowley and Jacobs, 2003), but also game universes (Gee & Hayes, 2010). Barron (2006) described how schools or the library structured the technology interests of adolescents (unintentionally) by providing opportunities for pursuit while simultaneously reporting how the pursuing interest may occur with friends and family, not structured by any formal organization.

Cultural

The last dimension indicates the norms, values, and rules structuring adolescents’ interest pursuits. Pursuing interest in an online Harry Potter universe is structured by the rules of the game, communication norms, and valued behavior by other members (Ito et al., 2019). Seemingly, when pursuing an interest in model rocketry, an extended family visiting a launching site was appreciated in one case but discouraged during another (Azevedo, 2011). Such uniformly structured culture seems absent within adolescents’ technology interests, pursued more flexibly within school, with family, or with peers (Barron, 2006).

Although discussed separately, differences in adolescents’ interest pursuits can be identified when all dimensions are considered. For example, the technology interests as studied by Barron (2006) are seemingly less tied to one specific place, specific others, or one institution compared to the description of being interested in The Sims (Gee & Hayes, 2010), even though both studies explored interest pursuits in technology.

Interest pursuit differences

Together, these seven dimensions can reveal large differences in interest pursuits. More specifically, the existing literature contains descriptions of highly structured interest pursuits on multiple dimensions, for example, how the location where amateur astronomers watch the night sky interacts with the moments when the cosmos is observed best (Azevedo, 2013). On the other hand, descriptions of less structured interest pursuits not tied to one interest-based practice can also be found, for instance, teenagers pursuing their interest more freely with various relations (peers, family, and teachers), at a variety of locations (home, school, and libraries), and not being tied to a specific moment (Barron, 2006).

The differences between interest pursuits are possibly even larger than reported in the literature thus far, considering that most research typically focusses on “productive interests” (i.e., interests that can be linked or consolidated in education, study, or (future) work (e.g., Ito et al., 2019; Gee & Hayes, 2010). Research where adolescents could self-define their interests indicates that adolescents have a wider variety of interests (Slot et al., 2019, 2020), and that there are interests that adolescents themselves (come to) consider productive for their future that are not initially recognized as productive (e.g., gaming in Vulperhorst et al., 2020). Also, there are reports of sustained interests mainly serving relaxation in the moment (Slot et al., 2020) instead of sustaining interests to reach a (future) goal (Hofer, 2010).

It seems plausible that differences between interest pursuits are not only object-related, but also involve the preferences of adolescents regarding their interests, as well as their opportunities or lack thereof. For example, parents do not have equal means to support the technology interests of their children, both financially and in terms of being knowledgeable (Barron, 2006).

The present study

We investigate the different ways in which sustained interests are pursued within the daily lives of adolescents, at a given moment in time. Through the lens of seven dimensions, we will employ latent class analyses to systematically map the different configurations of 820 interest pursuits. We expect quantitative differences, with some interest pursuits being structured on all seven dimensions based on descriptions within specific interest-based practices seemingly structured within all dimensions (e.g., Azevedo, 2011; Gee & Hayes, 2010). We also expect to find interest pursuits less structured within the dimensions, echoing descriptions of interest pursuits in and across a variety of practices (e.g., Akkerman & Bakker, 2019; Barron, 2006). Additionally, next to more quantitative differences, we expect to find qualitative differences in the way interest pursuits are structured, possibly due to adolescents’ opportunities in life. The research question we posed was, what configurations of the interest pursuits of adolescents are indicated by the temporal, epistemic, material, geographic, social, institutional, and cultural dimensions?

Interest is key in the development of adolescents towards who they are and who they want to be (Hofer, 2010; Krapp, 2002). The configurations of adolescents’ interests might indicate how sustained pursuits are inherently contextual and how contextual elements may also be favorable to capture one’s attention and trigger interest (Renninger, 2000, 2009). Although we study interest pursuits at a given moment in time, reported interest pursuits entail (all) experienced history of adolescents with their interest. Therefore, the configurations could help understand why and how (educational) environments may foster more sustained interests that benefit adolescents’ wider development, or when and why this might be (too much of) a challenge (e.g., Renninger & Hidi, 2020). Unraveling the structures of adolescents’ interest pursuits within daily life will help interpret the rich case studies and also inform researchers, educators, and parents about the complexity of individual interest pursuits, beyond the topical content of adolescents’ interest.

Method

Participants

Within this study, 410 adolescentsFootnote 1 from nine different secondary and three tertiary education institutes within the Netherlands participated (see Table 1 for an overview). All participated in a larger project regarding their interest pursuits.

Instrument

A questionnaire regarding the participants’ most important interests was developed to systematically map differences in their interest pursuits (Akkerman & Bakker, 2019), starting with an open question about how adolescents pursued their interest and what pursuing their interest entailed. This is used in the results to exemplify our findings. At the start, adolescents were asked to select their two most important interests from the list of all their personal interests communicated within the larger project, resulting in 820 interests. Filling in a new interest was possible. Eight adolescents added one new interest, which was either a generalization, specification, or clustering of already communicated interests. As questioning adolescents about all their interests was impossible due to time constraints, we chose to have them self-select their two most important interests without additional information about related forms of pursuit or to include typical practices (e.g., hobbies/school/social/future goals). This resulted in a variety of studied interests, ranging from highly specific to more general self-defined interests, and from academic to more out-of-school interests (e.g., accountancy, schoolwork computer science research, traveling, chilling, driving my scooter, sporting in the gym). Furthermore, we assumed adolescents would be able to answer questions regarding their interest structure, given that important interests are often sustained over a longer period (Krapp, 2002; Prenzel, 1992), leading to studying interest with similar meaning for all adolescents.

Questions were presented with answer options regarding each individual dimension (see left side of Table 2). Within the social and institutional dimensions, adolescents could identify additional answers. See online supplemental materials A for these responses. Based on our pilot with different educational trajectories, some questions were rephrased to resolve ambiguity.

Procedure

Adolescents received a personalized link (developed and conducted within Qualtrics, Provo, UT) in October 2018 with instruction about three parts of the questionnaire: (1) choosing their two most important interests, (2) questions about one of the chosen interests, and (3) followed by (almost) the same questions about their second interest. They were instructed to answer open-ended questions “as detailed as possible” and closed questions with a sliding scale (0–100). Once adolescents completed the questionnaire (and other obligations for the larger research project), they were granted financial compensation (€10). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences of our university.

Preparatory analyses

In preparation for the latent class analyses, we created an indicator for each dimension based on categorical and open-ended questions which represents the degree to which interest pursuits show a notable structure within each dimension. Table 2 shows the questions, answering options, and which answering option resulted in the created indicators for each dimension. See online supplemental materials B for more elaboration on the preparatory analyses.

Data analyses

Latent class analyses (LCA; Wolfe, 1970) were conducted with Mplus 7.2 (Muthen & Muthen, 2015). We took nesting and non-independence of observations (two interests per adolescent) into account by adjusting standard errors and chi-square tests of model fit (TYPE = COMPLEX in Mplus; Muthen & Muthen, 2015). See online supplemental materials C for a complete elaboration.

The conducted LCA, in which the 820 interest pursuits were assigned to classes based on empirically distinctive patterns in the seven dimensions, indicated which of the one- to seven-class models best fit the data. A one-class model would suit the data best when interest pursuits are homogeneously categorized; one of the multi-class models would suit the data best when a more heterogeneous categorization is most accurate. The model is displayed in Fig. 1. The variances were restricted to being equal across classes conforming to the Mplus default, since our research question is primarily focused on differences between different class solutions and the shape of the final solution. We used the default maximum likelihood estimator in Mplus with 1000 random starts and 20 iterations in all models.

We included the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), Akaike information criterion (AIC), and adjusted BIC to indicate which model represented the data best, with lower values indicating a better solution compared to the previous. Additionally, an entropy of minimally 0.70 was required to ensure class assignment accurately (Meeus et al., 2010). However, the most important criterion is additional classes reflecting a meaningful addition. As such, the relation to theory, the nature of the groups, and the interpretation of the results are also taken into account when choosing the solution that makes the most sense (Marsh et al., 2009).

Results

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics of the degree to which interest pursuits are structured along separate dimensions. Noteworthy are the differences along individual dimensions. For example, while more than half of the interests were not structured temporarily (i.e., could be pursued at any time), only 5% of interest pursuits were not structured geographically (i.e., could be pursued anywhere). Similarly, adolescents reported a preference, habit, or need for others in 80% of reported interests, indicating a relatively high degree of social structuring.

Latent class analyses

Regarding the model fit of our LCA, the AIC, BIC, and adjusted BIC decrease as the number of classes increases, except for the BIC in the five-class and the adjusted BIC in the seven-class model (see Table 4). With entropy values above 0.70 for all solutions, this indicates good class separation, meaning that interests can be assigned to classes accurately in all models. Most importantly, the five-class solution did not statistically improve the model fit as assessed by the LO-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT). This indicates that every model with an additional class up to the fourth class is an improvement on the previous model.

When comparing class interpretability of both solutions (Marsh et al., 2009; Meeus et al., 2010), we concluded that all classes within the four-class solution were interpretable: two identifiable classes relating to expectations based on theory (green and blue lines) and two highly distinctive classes (orange and yellow lines) (see Fig. 2). Within the five-class solution, the two expected classes based on theory were less clearly identified, and the variations within the three remaining classes were less meaningful due to the overlapping characteristics (black and yellow line); hence, the four-class model was selected.

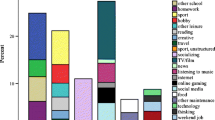

Distribution of the classes across the seven dimensions, for three-, four-, and five-class solutions (To enhance visual representation, within Figs. 2 and 3, we rescaled all categorical indicators to a scale of 0 to 100. For categorical indicators, we calculated the mean values based on the percentage for each categorical scale multiplied with their ordinal scale (0 to 3; 0 to 2 within the institutional dimension). This mean was adjusted to a scale from 0 to 100 (e.g., within the four-class solution, the temporal dimension for the green line was calculated by 0 × .078 + 1 × .047 + 2 × .632 + 3 × .243) × (100/3) = 68.00).

Four interest configurations

The four-class model contains two configurations characterized as being the (relative) extreme along all seven dimensions of interest and two configurations characterized by variating pattern of interest pursuits structured on some but not all dimensions. We describe how interest pursuit is structured within each configuration from most to least frequently assigned interest pursuitsFootnote 2 including examples. In light of our sample, we checked whether assigned interest configurations are related to adolescents’ gender or educational trajectory. Assigned classes were in line with the relative proportions of the total sample, indicating that there is no relation between assigned interest configuration and either gender or educational trajectory.

Semi-structured, expertise-oriented interest pursuits

The largest configuration was semi-structured, expertise-oriented interest pursuits, containing 41% (n = 336) of all interests (Fig. 3, yellow lineFootnote 3). Most pursuits in this configuration are characterized by specific knowledge and/or skills but are less uniform within other dimensions, typically characterized by either specific moments or rhythm, used materials, specific locations, or participation by significant others within institutions, meaning that “pursuing interest includes specific knowledge and/or skills (development), and either a specific moment, a specific place, usage of specific materials, with the involvement of significant others and (institutional) related norms, values and rules, but never all of these combined” when adolescents pursue interests with a semi-structured, expertise-oriented interest pursuit.

Four configurations of the final solution. Dotted lines indicate answer options selected in > 40% of the cases. (For example, of all limitedly structured, social-oriented interest pursuits, > 40% of adolescents indicated that others were a necessity when pursuing interest and > 40% indicated no institutional affiliation)

A wide variety of objects of interest were characterized as semi-structured, expertise-oriented pursuits. In their descriptions, adolescents typically emphasized how their interest pursuit was characterized by knowledge and skill (development). For example, the “music” interest pursuit of HannaFootnote 4 (17, senior general secondary education) included specific knowledge and skills, usage of musical devices, and following channels on YouTube/blogs/vlogs/social media/podcasts, and she experienced interest-specific norms, values, and rules:

I search for new songs on Spotify by rising or unknown artists, or songs that are popular. I often listen to the lyrics, when it’s in another language I look them up. Sometimes when I’m listening to a song that I know has really great lyrics, I look it up while playing the song on Genius. I just find that I can appreciate the music so much more when I can actually read the lyrics.Footnote 5

All “drawing” (n = 12) and “eating healthy” (n = 5) interest pursuits reported by adolescents were semi-structured in their expertise orientation. For example, Amy (17, pre-university student) stated that she “Look up recipes and make them when finding time” when pursuing her eating healthy interest, emphasizing wanting to become skilled in creating unknown dishes. Furthermore, she reported to only pursue cooking at home, with involvement of significant others, and following channels on YouTube/blogs/vlogs/social media/podcasts.

Structured interest pursuit

More than a quarter of the 820 studied interest pursuits showed notable structure within all seven dimensions (28% (n = 231)) (Fig. 3, green line), characterized by specific moments, including specific knowledge and/or skills, usage of interest-specific materials, (at least) one location designed for the interest, where involvement of significant others is a necessity or habit/preference, often organized by an institution, and when pursuing adolescents’ experienced interest-specific norms, values, and rules. “Only there, at that time, with those (knowledgeable) others and the right equipment following (institutional) related norms, values and rules” can adolescents pursue interests with a structured interest pursuit.

Within the structured configuration, pursuits were often related to interests which have recognizable institutions within the (Dutch) society. For example, all hockey (n = 15), korfball (n = 10), volleyball (n = 8), horse riding (n = 7), scouting (n = 6), fighting sports (n = 5), and water polo (n = 5) interest pursuits of adolescents were structured interest pursuits, possibly due to being organized within the Dutch hobby clubs. An example of this is Lily (16, senior general secondary education) and her “korfball” interest:

I train every Tuesday and Thursday night and on Saturday, I play a match. This applies to the indoor season which has just started. During the field season, I don’t train on Tuesday but on Monday night, which is the only difference.

Furthermore, noteworthy is that most of the reported “productive” interests of adolescents were structured interest pursuits, for example, work (6 of 10), internship (5 of 6), and medicine (4 of 6).

Limitedly structured, social-oriented interest pursuits

Almost one-fifth (18%, n = 144) of studied interest pursuits were characterized by involvement of significant others (Fig. 3, orange line). Additionally, interest pursuits were often characterized by locations designed for social interaction such as bars, cafes, restaurants, and houses of friends and families. In contrast, they were characterized by being less tied to specific moments, specific materials, or specific knowledge and/or skills. Notable was that interest pursuit was most often characterized as not being tied to formal institutions and without interest-specific norms, values, and rules. “Only with these significant others and preferably at that place, but anytime, with any materials, and without (institutional) related norms, values and rules” can adolescents pursue limitedly structured social-oriented interest pursuits.

Most names formulated by adolescents for these pursuits explicitly included significant others or communication, for example, “meeting friends” (48 out of 57 pursuits were limitedly structured, social-oriented), “talking” and “chatting” (33 of 47), “chilling with friends” (12 of 19), and “family” (10 of 16). Serena, a 19-year-old vocational student, stated about her “talking” interest: “I can have a conversation for example at home, or at school, at football or when I meet someone in the street.” It should be noted that some interest pursuits did not explicitly mention significant others, although the (online) presence of others is implied (e.g., going to concerts/going out, watching movies, gaming). As such, the focus of pursuits in this configuration is not exclusively on communication, as described by Morgan (16, senior general secondary education) regarding her “being with family” interest: “It’s mostly talking, or watching a film together, or walking around town or something like it.”

Unstructured interest pursuit

Thirteen percent of all interests (n = 109) were assigned to the unstructured configuration (Fig. 3, blue line). Unstructured interest pursuits are characterized by being the least structured within all dimensions compared to other configurations. Interest pursuits were characterized by experiencing interest that can happen at any moment, not including specific knowledge and/or skills, mostly not linked to any societal institution and without interest-specific norms, values, and rules. Additionally, unstructured interest pursuits were characterized by the usage of materials and locations not specific to the interest itself and without involvement of significant others. Interest pursuits within the unstructured configuration can happen “anywhere, anytime, with generally available materials and without significant others or (institutional) norms, values and rules.”

Interest pursuits within the unstructured configuration were described by adolescents as interest that they encountered throughout their lives. Emmy (18, following pre-university education) described pursuing her “going outside” interest as: “When I cycle to school I am always outside, or when I go into the woods. When I am in the city I walk, shop or cycle there.” Eleven of 14 “Netflix” interest pursuits were unstructured. Regarding pursuing his “Netflix” interest, Geovanni stated: “Well, I watch Netflix on my phone or iPad, or on my computer or TV,” implying an unstructured interest pursuit. Other interest pursuits often reported as unstructured by adolescents were “YouTube”- (8 of 10) and “reading”- (12 of 18) labeled interests.Footnote 6

Similar object, different interest pursuits

Within the descriptions of the four configurations above, we highlighted interest pursuits of seemingly similar interests (i.e., having (partly) the same or a similar name) that ended up mainly or solely within one of the four configurations. However, we simultaneously observed seemingly similar interests being assigned to different configurations. For example, of the eighteen reported interests in “cooking,” “baking,” and/or “eating,” ten were semi-structured, expertise-oriented interest pursuits; two structured interest pursuits; four limitedly structured, social-oriented interest pursuits; and two unstructured interest pursuits. Here, Imani (a 22-year-old university student) elaborated on her limitedly structured, social-oriented interest pursuit:

I see dinner very much as a social activity. It’s a nice moment to discuss your day and to keep up to date on the lives of close friends. I get a lot of energy from doing fun things with my friends. I also enjoy cooking together. Eating out with friends is therefore an important activity for me.

This is very different from the description of Mia (21, senior general education) whose interest pursuit was semi-structured, expertise-oriented:

Food is actually my main interest. I am busy thinking about it every day. This includes looking up dishes, cooking, going to restaurants, trying new things, going to the supermarket. I often try to keep it healthy and find out more about it by searching the internet. I like to be inspired by others. Usually through magazines, YouTube or Pinterest.

Similar contrasts in differently structured pursuits are found for other objects of interests. For example, in contrast to the elaboration of Hanna’s “music” interest pursuit, which focused on the lyrics and appreciation of music and therefore characterized as semi-structured, expertise-oriented (see the “Four interest configurations” section), is the “listening to music” interest of Meghan (16, general secondary education). This interest pursuit was identified as unstructured (as were 12 other “music” interest pursuits). She stated: “I listen to music almost all the time, even now when I am filling in this survey. It just provides some distraction and makes things less boring.”

Discussion

To unravel contrasting findings of existing case studies on the contextuality of sustained interest pursuits, we systematically mapped the differences in 820 interest pursuits in terms of the temporal, epistemic, material, geographic, social, institutional, and cultural dimensions that have been advanced as indicative for differences in pursuing interests (Akkerman & Bakker, 2019). Latent class analyses identified four configurations of interest pursuits.

The largest configuration (41%) contained semi-structured, expertise-oriented interest pursuits. These interest pursuits are primarily characterized by adolescents learning or having mastered specific knowledge and/or skills. Interest pursuits characterized by knowledge and skill seem to be in line with the widespread understanding of interests as being content-driven, oriented towards learning and mastering (e.g., Hidi & Renninger, 2006). It seems realistic that these interests have “productive” potentials even when not (yet) recognized as such by institutions (Ito et al., 2019) or by adolescents themselves (Vulperhorst et al., 2020). As semi-structured interest pursuits are not as tied to all dimensions, these interests appear potentially pursuable anytime, anywhere, or anyhow, rather than being dependent on an entire social and material practice. Such interests show, therefore, a more fluid and cross-contextual nature (e.g., Akkerman & Bakker, 2019; Barron, 2006; Slot et al., 2019).

Structured interest pursuits (28%) were most strongly defined on all dimensions. This configuration reflects findings of research on specific interest-based practices (e.g., Azevedo, 2011, 2013) where interest pursuits are structured within all seven dimensions. Typical structured-pursued objects of interest were sports and hobbies which are, in the Netherlands, often found in a communal form of institutionalized leisure practices, or objects that can be deemed productive (e.g., internships, school/study, or work interests), offered by (educational) institutions. By their very relational and contextual nature, structured interest pursuits are less likely to be pursued across a wide variety of other life contexts.

Combined, 69% of all studied interest pursuits were (semi-)structured. Within these pursuits, adolescents reported pursuing interest (in various degrees) at specific moments, including specific knowledge/skills, using specific materials, meeting at specific places, preferably or out of necessity with significant others, supported by institutions, and following interest-specific norms, values, and rules. As such, (semi-)structured interest pursuits emphasize the inherent contextuality of more sustained interests, comparable to the way in which “situational” interests are often “triggered” by elements from adolescents’ (social) contexts within daily life (Renninger, 2000, 2009).

Unstructured interest pursuits (13%) were least structured within all dimensions. Reported interest pursuits were often content-flexible, meaning that these interests concerned activities or digital platforms that can take the shape of any content. Such content-flexible objects of interest seem to offer limitless opportunities to pursue these interests within daily life in the experience of adolescents, since digital devices are always at hand (e.g., see Geovanni’s “Netflix” interest), or require materials that adolescents presume to be present (i.e., multiple adolescents indicated not using materials regarding their reading or digital interests, even though (electronic) books or devices are plausibly required). However, pursuing interest always manifests within a specific context, impacting the actual experience of interest (Draijer et al., 2022).

Limitedly structured, social-oriented interest pursuits (18%) are characterized by the presence of significant others as well as by (multiple) locations designed for people to meet. Compared to semi-structured, expertise-oriented interest pursuits, social-oriented interest pursuits were more homogeneous in being less structured by time, knowledge and/or skills, specific materials, institutions, or interest-specific norms, values, and rules. It should be noted that in unstructured pursuit interest can unfold at any moment; it by no means implies that this interest will materialize in any setting, as how someone experiences an interest within a given moment is complex and to some extent unpredictable (Draijer et al., 2022).

The identified (semi-)structured and unstructured configurations found in this study resonate with three forms of interest pursuits suggested by Akkerman and Bakker (2019). Yet, limitedly structured, social-oriented interest pursuits are, to our knowledge, not yet described within the literature as such, even though empirical work has illustrated the important role significant others can have in motivating pursuing interests (e.g., Ito et al., 2019).

Implications for practice and policy

Overall, our findings imply for all those involved to mobilize the rich variety of adolescents’ practices as resources to support adolescents’ interest (Akkerman & Van Eijck, 2013), yet the identified configurations may also call for various types of guidance from parents and educators and impose challenges for policy makers.

(Semi-)Structured interest pursuits may call for more conscious reflection, since existing (educational) structures may be experienced differently by adolescents. Due to their structured nature, these interest pursuits seize scarce resources of adolescents (e.g., time, funds, or (social) attention). Here, parents may play a vital and important role by periodically discussing with their children the structural practices that make up children’s daily life. Furthermore, (semi-)structured interest pursuits challenge policy makers in thinking about how to make and keep all practices accessible for all adolescents (Renninger & Hidi, 2020).

With some exceptions, unstructured interest pursuits seem to be pursued to relax without any other (future) purpose. Therefore, these pursuits may seem less promising for policy makers, educators, or parents to focus on when wanting to help adolescents developing into adulthood. However, our findings indicate that some adolescents report such interest to be one of their most important interests. Moreover, these interests also appear important for adolescents to recuperate from other, more productive, interests (Draijer et al., 2022; Slot et al., 2020). Similarly, limitedly structured, social-oriented interest pursuits less clearly include specific knowledge and skills. These interest pursuits help remind educators, policy makers, and perhaps also parents to take into account the interests of adolescents that involve more soft skills (Heckman & Kautz, 2012; Schulz, 2008), i.e., being a people person, when aiming for the consolidation of interests into more productive activities.

Studying the contextuality of interest pursuits highlights the (im)possibilities of adolescents’ daily lives. For example, an interest in film may result in wanting to visit a (Hollywood) filmset, which is only within the range of possibilities for some adolescents. Additionally, the object of interests may afford some pursuit configurations and exclude others (e.g., some musical instruments are easier transported compared to others), and environmental and societal structures also make some pursuits more likely than others (e.g., there are no snow-capped mountains within the Netherlands). As such, it appears plausible that individual-, societal-, and object-related opportunities and constraints culminate in adolescents’ interest pursuits with different structures. Recognizing these differences appears essential for educators, policy makers, and parents to support adolescents’ interests.

Limitations

Asking adolescents to select their two most important interests might have resulted in a specific range of interest pursuits. Yet, the broad range of reported interests seems to indicate that we have captured a wide variety of pursuits. However, only a few interests were reported to be pursued anywhere (5%) or without the participation of anyone (2%), whereas adolescents pursuing an interest alone are often observed (e.g., Akkerman & Bakker, 2019; Slot et al., 2019, 2020). This could mean that our sample underrepresents interests that might be pursued alone.

Second, we asked participating adolescents to aggregate all their experiences of interests into an interest pursuit. Yet, interest experiences likely materialize in interest-driven practices as well as more self-guided and self-paced practices (c.f. Azevedo, 2019), and how such a pursuit is aggregated by an adolescent might differ per individual. Yet, all adolescents could identify each dimension for their interest pursuits (except for one institutional dimension), which convinced us that our participants reported their perception of how they generally experience the contextuality of their sustained interests.

Future research

The four identified configurations show that pursuing interests entails more than a preference for an object, but also a preference for, and in some cases a possible necessity of, a wider contextual configuration. Differences in resources translate into unequal opportunities to pursue interests, or possibly even in considering particular objects as possible interests. Therefore, we concur with the necessity of supporting interest pursuits to balance individual inequalities (Renninger & Hidi, 2020). This study should be seen as a first step, suggesting that distinctive support may be indispensable. Further research explicitly focusing on differences between adolescents would increase our understanding of how (differences in) interest pursuits come to exist in adolescents’ daily life.

Besides individual differences, interests manifest differently within adolescents’ daily lives (Draijer et al., 2020; Hidi & Renninger, 2006). It would be interesting to explore whether different manifestations of interests appear in different contextual configurations. Additionally, given that manifestations of adolescents’ interests may develop (Akkerman et al., 2020), studying to what extent and in what ways adolescents’ interest configurations change over time is necessary moving forward.

Our study hints at potential differences in societal opportunities to pursue specific objects of interest. For example, almost all team sports and most hobby-like interests were structural pursuits reflecting how these interests are organized within the Netherlands. In contrast, two-thirds of reading interests were identified as unstructured pursuits, possibly as reading is typically taken up individually. Research towards differences in societal opportunities for specific interests may clarify how certain objects may provoke certain pursuits and whether typical interest pursuits are possible for (all) adolescents to fit in their lives. A better understanding of possible normative forces within society could help us understand and identify opportunities for adolescents to consolidate their interests within (future) productive activities or sustain them within their daily lives.

Lastly, as our study shows that pursuing interests in daily life is inherently contextual, we hope that this contextuality in its different configurations will be included in future research and considered when trying to consolidate and/or nurture adolescents’ interests.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [G.J.Beek, g.j.beek@uu.nl], upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Notes

We are aware that some young participants in our study are nearing early adulthood. However, all studied individuals are in a developing stage of their lives as they are following some type of formal education. We prefer using the term “adolescents” over “students” to emphasize that the lives of those participating in our study entail more contexts of participation than one single institutionalized educational organization.

For the sake of interpretation, class membership is fixed in the remainder of the article, meaning that each interest is assigned to a configuration by the highest posterior class-membership probability.

The representation of the semi-structured, expertise-oriented configuration (see Fig. 3, yellow line) conceals the variety within the individual dimension as it represents the mean of highly different pursuits.

The names used within the text are pseudonyms.

Within the questionnaire, adolescents provided a written explanation about how they pursued their interest in general. From these descriptions, we selected exemplary statements of adolescents for what we aimed to illustrate.

Although the exemplified interests typically do require materials (e.g., a device or book), some adolescents reported not needing any materials when pursuing their interests, while others only indicated materials that are not specific to their interest (e.g., a smartphone for a YouTube or Netflix interest; online supplemental materials B). We elaborate on this finding in the “Discussion” section.

References

Akkerman, D. M., Vulperhorst, J. P., & Akkerman, S. F. (2020). A developmental extension to the multidimensional structure of interests. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(1), 183.

Akkerman, S. F., & Bakker, A. (2019). Persons pursuing multiple objects of interest in multiple contexts. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-018-0400-2

Akkerman, S. F., & Van Eijck, M. (2013). Re-theorising the student dialogically across and between boundaries of multiple communities. British Educational Research Journal, 39(1), 60–72.

Azevedo, F. S. (2019). A pedagogy for interest development: The case of amateur astronomy practice. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 23, 100261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.11.008

Azevedo, F. S. (2011). Lines of practice: A practice-centered theory of interest relationships. Cognition and Instruction, 29(2), 147–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2011.556834

Azevedo, F. S. (2013). The tailored practice of hobbies and its implication for the design of interest-driven learning environments. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 22(3), 462–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2012.730082

Barron, B. (2006). Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective. Human Development, 49(4), 193–224. https://doi.org/10.1159/000094368

Barron, B., Martin, C. K., Takeuchi, L., & Fithian, R. (2009). Parents as learning partners in the development of technological fluency. International Journal of Learning and Media, 1(2), 55–77.1063. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000327

Crowley, K., & Jacobs, M. (2002). Building islands of expertise in everyday family activity. In G. Leinhardt, K. Crowley, & K. Knutson (Eds.), Learning conversations in museums (pp. 333–356). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Crowley, K., Barron, B. J., Knutson, K., & Martin, C. K. (2015). Interest and the development of pathways to science. In K. A. Renninger, M. Nieswandt, & S. Hidi (Eds.), Interest in mathematics and science learning and related activity (pp. 297–313). American Educational Research Association.

Draijer, J., Bakker, A., Slot, E., & Akkerman, S. (2020). The multidimensional structure of interest. Frontline Learning Research, 8(4), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v8i4.577

Draijer, J., Bronkhorst, L., & Akkerman, S. (2022). Manifestations of non-interest: Exploring the situated nature of students’ interest. International Journal of Educational Research, 113, 101971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2022.101971

Deci, E. L. (1992). The relation of interest to the motivation of behavior: A self-determination theory perspective. In K. A. Renninger, S. Hidi, A. Krapp, & A. Renninger (Eds.), The role of interest in learning and development (pp. 43–70). Psychology Press.

DiGiacomo, D. K., Van Horne, K., Van Steenis, E., & Penuel, W. R. (2018). The material and social constitution of interest. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 19, 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.04.010

Gee, J. P., & Hayes, E. (2010). Women and gaming: The Sims and 21st century learning. Palgrave Macmillan.

Harackiewicz, J. M., Smith, J. L., & Priniski, S. J. (2016). Interest matters: The importance of promoting interest in education. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(2), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732216655542

Heckman, J. J., & Kautz, T. (2012). Hard evidence on soft skills. Labour Economics, 19(4), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2012.05.014

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

Hidi, S. E., & Renninger, K. A. (2019). Interest development and its relation to curiosity: Needed neuroscientific research. Educational Psychology Review, 31(4), 833–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09491-3

Hofer, M. (2010). Adolescents’ development of individual interests: A product of multiple goal regulation? Educational Psychologist, 45(3), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2010.493469

Hollett, T. (2019). Symbiotic learning partnerships in youth action sports: Vibing, rhythm, and analytic cycles. Convergence, 25(4), 753–766.

IJdens, T. (2015). Kunstzinnig en creatief in de vrije tijd: Monitor Amateurkunst 2015. LKCA.

Inspectie van het Onderwijs (2021). De staat van het onderwijs 2019/2020. Inspectie van het Onderwijs.

Ito, M., Martin, C., Pfister, R. C., Rafalow, M. H., Salen, K., & Wortman, A. (2018). Affinity online: How connection and shared interest fuel learning (Vol. 2). NYU Press.

Ito, M., Martin, C., Pfister, R. C., Rafalow, M. H., Salen, K., & Wortman, A. (2019). Affinity online: How connection and shared interest fuel learning. NYU Press.

Krapp, A. (2002). Structural and dynamic aspects of interest development: Theoretical considerations from an ontogenetic perspective. Learning and Instruction, 12(4), 383–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(01)00011-1

Marsh, H. W., Ludtke, O., Trautwein, U., & Morin, A. J. (2009). Classical latent profile analysis of academic self-concept dimensions: Synergy of person-and variable-centered approaches to theoretical models of self-concept. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 16(2), 191–225. https://doi.org/10.2307/30047170

Maul, A., Penuel, W. R., Dadey, N., Gallagher, L. P., Podkul, T., & Price, E. (2017). Measuring experiences of interest-related pursuits in connected learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65(1), 1–28.

Meeus, W., Van De Schoot, R., Keijsers, L., Schwartz, S. J., & Branje, S. (2010). On the progression and stability of adolescent identity formation: A five-wave longitudinal study in early-to-middle and middle-to-late adolescence. Child development, 81(5), 1565–1581. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01492.x

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (2015). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Muthen & Muthen.

Prenzel, M. (1992). The selective persistence of interest. In K. A. Renninger, S. Hidi, A. Krapp, & A. Renninger (Eds.), The Role of interest in Learning and Development. Psychology Press.

Renninger, K. A. (2009). Interest and identity development in instruction: An inductive model. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520902832392

Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. E. (2020). To level the playing field, develop interest. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 7(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732219864705

Renninger, K. A. (2000). Individual interest and its implications for understanding intrinsic motivation. In C. Sansone & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (pp. 373–404). Academic Press.

Rotgans, J. I., & Schmidt, H. G. (2011). The role of teachers in facilitating situational interest in an active-learning classroom. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 37–42.

Schiefele, U., & Rheinberg, F. (1997). Motivation and knowledge acquisition: Searching for mediating processes. Advances in Motivation and Achievement, 10, 251–301.

Schulz, B. (2008). The importance of soft skills: Education beyond academic knowledge. Journal of Language and Communication, 2, 146–154.

Skalstad, I., & Munkebye, E. (2022). How to support young children’s interest development during exploratory natural science activities in outdoor environments. Teaching and Teacher Education, 114, 103687.

Slot, E., Akkerman, S., & Wubbels, T. (2019). Adolescents’ interest experience in daily life in and across family and peer contexts. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-018-0372-2

Slot, E. M., Bronkhorst, L. H., Wubbels, T., & Akkerman, S. F. (2020). The role of school in adolescents’ interest in daily life. International Journal of Educational Research, 104, 101643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101643

van der Poel, H., Hoeijmakers, R., Pulles, I., & Tiessen-Raaphorst, A. (2018). Rapportage sport 2018. Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

Vulperhorst, J. P., van der Rijst, R. M., & Akkerman, S. F. (2020). Dynamics in higher education choice: weighing one’s multiple interests in light of available programmes. Higher Education, 79(6), 1001–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00452-x

Wolfe, J. H. (1970). Pattern clustering by multivariate mixture analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 5(3), 329–350. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr0503_6

Acknowledgements

We thank Jael Draijer, Alexandros Janse, and Thea van Lankveld for their contribution in the design of the questionnaire and data collection. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 716183.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Gregorius J. Beek. Department of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands. E-mail: g.j.beek@uu.nl

Current themes of research:

Interest development. Interest development and adolescent situatedness.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

No previous publications.

Larike H. Bronkhorst. Department of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands. E-mail: l.h.bronkhorst@uu.nl

Current themes of research:

Learning, development, and collaboration across contexts.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Draijer, J., Bronkhorst, L., & Akkerman, S. (2022). Manifestations of non-interest: Exploring the situated nature of students’ interest. International Journal of Educational Research, 113, 101971.

Liu, M., Zwart, R., Bronkhorst, L., & Wubbels, T. (2022). Chinese student teachers’ beliefs and the role of teaching experiences in the development of their beliefs. Teaching and Teacher Education, 109, 103525.

Arts, M., & Bronkhorst, L. H. (2020). Boundary crossing support in part-time higher professional education programs. Vocations and Learning, 13(2), 215–243.

Slot, E. M., Bronkhorst, L. H., Wubbels, T., & Akkerman, S. F. (2020). The role of school in adolescents’ interest in daily life. International Journal of Educational Research, 104, 101643.

Sanne F. Akkerman. Department of Educational Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands. E-mail: s.f.akkerman@uu.nl

Current themes of research:.

Social, organizational, and disciplinary boundaries of students and professionals. Boundary crossing. Challenges faced by adolescents.

Most relevant publications in the field of Psychology of Education:

Draijer, J., Bronkhorst, L., & Akkerman, S. (2022). Manifestations of non-interest: Exploring the situated nature of students’ interest. International Journal of Educational Research, 113, 101971.

Slot, E. M., Bronkhorst, L. H., Wubbels, T., & Akkerman, S. F. (2020). The role of school in adolescents’ interest in daily life. International Journal of Educational Research, 104, 101643.

Akkerman, S. F., & Bakker, A. (2019). Persons pursuing multiple objects of interest in multiple contexts. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34(1), 1–24.

Slot, E., Akkerman, S., & Wubbels, T. (2019). Adolescents’ interest experience in daily life in and across family and peer contexts. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34(1), 25–43.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Beek, G.J., Bronkhorst, L.H. & Akkerman, S.F. Unraveling the contextuality of adolescents’ interest pursuits in daily life: four latent configurations. Eur J Psychol Educ 39, 105–127 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00684-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-023-00684-7