Abstract

Previous research has shown that there are a variety of eHealth usability evaluation methods suitable for agile, easily applicable, and useful eHealth usability evaluations. However, it is unclear whether such eHealth usability evaluation methods are also applicable with elderly users. This study aims to examine the challenges in applying eHealth usability evaluation methods with elderly users and how these challenges can be overcome. We chose three established eHealth usability evaluation methods to evaluate an eHealth intervention: (1) Co-Discovery Evaluation, (2) Cooperative Usability Testing, and (3) Remote User Testing combined with Think Aloud. The case study was conducted with seven Austrian elderly users. We supplemented the case study (March, 2021) with a systematic review (March, 2022) to identify (1) applied eHealth usability evaluation methods to elderly and (2) challenges of eHealth usability evaluations with elderly. Our results showed that Remote User Testing combined with Think Aloud could successfully be applied to evaluate the eHealth intervention with elderly users. However, Cooperative Usability Testing and Co-Discovery Evaluation were not suitable. The results of the systematic review showed that user-based eHealth usability evaluation methods are mostly applied to conduct eHealth usability evaluations with elderly users. Overall, the results showed that not all established eHealth usability evaluation methods are applicable with elderly users. Based on the case study and the systematic review, we developed 24 recommendations on how to deal with challenges during eHealth usability evaluations. The recommendations contribute to improving the accessibility, acceptability, and usability of eHealth interventions by the elderly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Population aging occurs worldwide [1]. Due to increased aging of the population, eHealth systems are increasingly used by elderly people to enable them to live more independently [2, 3]. There are eHealth systems used by the elderly that promote physical activity [4, 5], mental health care [6, 7], ambulatory care [8, 9], or disease-related therapy (such as for diabetes) [10, 11]. eHealth systems designed for elderly users can be implemented for example as mobile Health (mHealth) systems [12, 13] or web-based eHealth systems [14, 15]. mHealth systems and web-based eHealth systems differ in terms such as realization (e.g., screen size) [16], application (e.g., enhancing educational skills) [17], or accessibility [18].

Accessibility, acceptability, and usability are vital factors to be considered when designing eHealth systems because eHealth interventions are produced very rapidly [19]. Accessibility means that prospective users can interact with a system (e.g., web-based eHealth system) [20, 21] irrespective of physical and physiological disabilities [22, 23]. Acceptability means that a newly developed system meets prospective users’ needs [24]. Usability means that the quality of a system is assessed with regards to the ease of use of user interfaces [25]. Due to the aging of population, the demand for eHealth systems designed, especially for the elderly is increasing. As a result, the usability of eHealth systems for elderly users is becoming increasingly important [26].

Incorporating the needs of the elderly into the development process of eHealth systems is possible by applying the User-Centered Design approach. User-Centered Design involves prospective users through an iterative development process [27]. By conducting eHealth usability evaluations during User-Centered Design, prospective users’ feedback is iteratively collected and considered to evolve eHealth systems. eHealth usability evaluations can be carried out using Usability Testing, typically in a usability laboratory, where prospective users are observed while performing tasks to gain user feedback [28, 29]. This traditional form of eHealth usability evaluation is difficult to reconcile through an iterative development process, so integrating agile, easily applicable, and useful eHealth usability evaluations into User-Centered Design is gaining importance.

Agile User-Centered Design involves usability evaluation methods into the iterative development process resulting in improved usability [30, 31]. Conducting agile, easily applicable, and useful eHealth usability evaluations to gain rapid user feedback during agile User-Centered Design is necessary to increase the usability of eHealth systems for elderly. To identify whether eHealth systems are designed appropriately for elderly, eHealth usability evaluations are conducted. To conduct eHealth usability evaluations user-based eHealth usability evaluation methods (e.g., Usability Testing) and expert-based eHealth usability evaluation methods (e.g., Cognitive Walkthrough) can be applied. In a Cognitive Walkthrough, an expert mentally walks through the steps required to complete tasks that prospective users would perform with an eHealth system [29].

Conducting a usability test with elderly users is challenging. Elderly users need more time to perform tasks, to read instructions for the tasks, and they often forget the meaning of the task to be performed [32]. Furthermore, there are elderly who do not want to join a usability evaluation in a usability laboratory due to illness [33]. Challenges arise during eHealth usability evaluation, however, also prior to and after eHealth usability evaluations are conducted. Prior to eHealth usability evaluations, rapid prototype testing can be conducted in which elderly users may have difficulties to participate because of cognitive or physical decline. For instance, after conducting eHealth usability evaluations user errors can occur with elderly using eHealth systems, which may also be difficult to manage for elderly users due to their age-related declines. These are some reasons why eHealth usability evaluation methods such as Usability Testing are not easily applicable to evaluate eHealth systems with elderly users [2]. Well-established eHealth usability evaluation methods such as Think Aloud or Cognitive Walkthrough are not readily applicable with elderly users who suffer from motivational, cognitive, or physical decline [34,35,36].

The aforementioned reasons demonstrate why it is essential that an appropriate eHealth usability evaluation method is chosen or modified to accomplish eHealth usability evaluations with elderly users.

We aimed to examine the following research questions: (1) Which eHealth usability evaluation methods are applicable to evaluate eHealth interventions with elderly users?, (2) What challenges might be encountered when conducting an agile, easily applicable, and useful eHealth usability evaluation with elderly users?, and (3) How to deal with and overcome these challenges that arise prior to, during, and after carrying out the eHealth usability evaluation conducted with elderly users?

2 Method

We conducted an explorative case-study supplemented with a systematic literature review to learn about challenges in applying eHealth usability evaluation methods with elderly users and how these challenges can be overcome (see Fig. 1). We implemented the systematic literature review subsequently to the case study to systematically identify and classify challenges corresponding to age-related barriers, such as cognition, motivation, perception, and physical abilities. We chose these four age-related barriers because they affect the usability of eHealth systems, particularly for elderly users [37]. We structured these challenges and developed recommendations according to the stages of software lifecycle (requirements engineering, design, and evaluation), taking into account the stage that follows the eHealth usability evaluation.

As a case study, we applied an eHealth usability evaluation of an eHealth intervention. This eHealth intervention is a web-based application that allows patients to decentrally retrieve diagnostic reports or prescriptions. Prospective users of the web-based eHealth intervention are elderly persons who suffer from diseases frequently or are chronically ill.

We combined these results of the case study with the systematic literature review to develop recommendations useful for conducting eHealth usability evaluations with elderly users.

2.1 Case study: set-up and procedure of eHealth usability evaluation

We started the case study by conducting a pre-test with one elderly person (March, 2021). The pre-test was made to rehearse the procedure and technical equipment used during the eHealth usability evaluation. After finishing the pre-test, we conducted the eHealth usability evaluation with six other elderly participants (see Table 1). We accomplished the pre-test as well as the case study in March, 2021.

The median age of the elderly was 70 years and each session of the eHealth usability evaluation lasted a median of 27 minutes.

2.1.1 Phase 1: Set-up of eHealth usability evaluation

To conduct the eHealth usability evaluation we (1) selected appropriate eHealth usability evaluation methods and, (2) defined inclusion and exclusion criteria to recruit elderly participants.

Selection of appropriate eHealth usability evaluation methods

We selected three eHealth usability evaluation methods: (1) Co-Discovery Learning, (2) Cooperative Usability Testing, and (3) Remote User Testing combined with Think Aloud. We chose the eHealth usability evaluation methods from a previously developed toolbox for eHealth usability evaluations, called ToUsE [38]. ToUsE consists of rapidly applicable as well as potentially useful eHealth usability evaluation methods suitable for implementing eHealth usability evaluations [39].

Co-Discovery Evaluation was selected because we aimed to give the elderly the opportunity to work on tasks during the eHealth usability evaluation together. Co-Discovery Evaluation means that two (or more) participants perform tasks simultaneously [35]. Research has shown that elderly prefer working on tasks together or with caregivers [40].

Cooperative Usability Testing was selected to combine domain expertise with human-computer interaction expertise due to the collaboration of the elderly and the researcher (First Author). Cooperative Usability Testing means that a video recording is made during the eHealth usability evaluation that is watched together with the elderly after the eHealth usability evaluation is conducted [41].

Remote User Testing combined with Think Aloud was selected because we aimed to give the elderly the opportunity to accomplish the eHealth usability evaluation at their homes. Recent research showed that no fully conducted Remote User Testing with elderly users can be found in the literature [42]. Generally, Remote User Testing means that the evaluator and participants are located at different physical locations [35]. During Think Aloud participants express their thoughts out loud when performing tasks [29].

We intended to apply all three chosen eHealth usability evaluation methods with all elderly participants (\(n=7\)). Therefore we invited all seven elderly patients to attend the eHealth usability evaluation with each chosen eHealth usability evaluation method.

Elderly participants

The study team consisted of a researcher (First Author), two software developers of the web-based eHealth intervention, and elderly patients from Austria as participants.

We selected seven elderly participants to conduct the eHealth usability evaluation because having five to seven representative users can identify 80% of the most important usability problems [43, 44]. After conducting the eHealth usability evaluation with the fourth participant, we noticed saturation. Saturation occurred because the indicated usability problems by the elderly repeated.

We restricted the residence of the elderly to Austria because we decided to implement the eHealth usability evaluation at participants’ homes to possibility of limited mobility among the elderly. Conducting the Usability Testing in the elderly’s personal environment is described as the gold standard in the literature [40].

Inclusion criteria for the elderly participants were as follows:

-

age equal to 60 years or above;

-

living independently;

-

chronically ill or suffering from a disease;

-

availability of e-mail account;

-

having basic knowledge of how to use a computer;

-

having an own computer or technical equipment; and

-

ability to understand and sign the written informed consent.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

no e-mail account;

-

residing outside of Austria (Europe);

-

no ability to understand and express themselves adequately in the German language; and

-

lack of signed written informed consent.

German language skills were required to accomplish the selected eHealth usability evaluation methods. Elderly persons that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were recruited through the researchers’ personal and professional surroundings.

2.1.2 Phase 2: Procedure of eHealth usability evaluation

We explained the procedure of the eHealth usability evaluation prior to the start of the evaluation to the elderly and asked them to sign a written informed consent. We explained to them that we were evaluating the web-based eHealth intervention and not the performance of the elderly users themselves.

We performed the eHealth usability evaluation in March, 2021. We attuned the whole set up of the eHealth usability evaluation to the physical and cognitive capacities of the elderly participants. We asked the elderly prior to the conduction of the eHealth usability evaluation whether they would prefer to use their own computer or a computer provided by the researchers (First Author).

We developed brief tasks to help the elderly maintain their concentration during the eHealth usability evaluation. To accomplish the development of the tasks, we defined a fictitious scenario. We planned sufficient time to explain the tasks to the elderly prior to the eHealth usability evaluation.

Scenario and tasks to accomplish eHealth usability evaluation

Table 2 shows the developed fictitious scenario and the brief tasks to accomplish the eHealth usability evaluation. We planned to apply the three chosen eHealth usability evaluation methods—Remote User Testing combined with Think Aloud, Cooperative Usability Testing, and Co-Discovery Learning—in different order for each participant to reduce the risk of influencing the results of successively performed eHealth usability evaluations.

We formulated a scenario and derived three tasks from the scenario. The scenario presumes that the elderly patient consented to receive the prescription via e-mail and therefore provided the physician with personal information (e-mail address and phone number). After receiving the e-mail notification, the prescription could be opened via the web-based eHealth intervention.

Figures 2, 3, 4 and 5 show the prototype of the web-based eHealth intervention. At the beginning, a Transaction Authentication Number (TAN) was sent to the phone number of the elderly patient as participant. In a first step, the elderly had to enter the received TAN in the input field of the front end of the web-based eHealth intervention (Fig. 2). After verification of the TAN, the prescription could be downloaded by the elderly in a second step (Fig. 3). After receipt of the prescription, there were two options in a third step: (1) Managing of the personal information to delete the personal information directly, otherwise the personal information will be deleted automatically after 10 days or (2) Closing of the front end of the web-based eHealth intervention (Fig. 4). In a fourth step, a final optional evaluation of the transmission of the prescription is possible (Fig. 5).

Data analysis of eHealth usability evaluation

We counted the number of usability problems that were described and indicated by the elderly. Some usability problems were indicated multiple times by the elderly. For example, some of the elderly stated that they had difficulties in distinguishing the color of the buttons. The usability problem “Difficulty in distinguishing color of buttons” was indicated in the course of two sessions of the eHealth usability evaluation, each carried out with one elderly participant. Therefore we counted this usability problem twice.

2.2 Systematic review: identifying challenges of eHealth usability evaluations with elderly

We performed the systematic literature review to (1) identify papers that report on applied eHealth usability evaluation methods to elderly users and (2) identify challenges of conducting agile, easily applicable, and useful eHealth usability evaluations with elderly users. The systematic literature review was conducted in March, 2022.

We searched four databases for relevant papers: ACM Digital Library, Cochrane Library, IEEE Xplore, and Medline (via PubMed). We used the following search terms related to the four thematic areas of this study (usability, eHealth, elderly, and challenges): eHealth, mHealth, “medical informatics applications”, elderly, elder*, senior, old, usability, “usability testing”, challenges, limitations, feasibility, acceptability, and applicability. For the search in Medline (via PubMed), we also encountered Medical Subject Headings terms, such as telemedicine, aged, and user-centered design. To ensure that we did not miss any relevant literature, we applied different combinations of search terms depending on the selected database.

We included papers that (1) were published in the last 10 years (2012–2022), (2) focus on eHealth interventions, and (3) report on challenges of eHealth usability evaluations with elderly users (see Table 3). In the interest of receiving a large number of relevant papers, we extended our search to papers reporting not only on challenges but also reporting about acceptability, applicability, or feasibility of eHealth usability evaluations with elderly. We also included findings on reported challenges with disabled participants because we did not want to exclude possible further relevant information from this related field.

We excluded (1) non-peer-reviewed papers (except conference papers), (2) papers that do not focus on eHealth interventions, and (3) papers not written in English. We did not restrict our search to papers that report only on user-based eHealth usability evaluations because we were also interested in reported challenges of eHealth usability evaluations where the usability was assessed by experts (expert-based eHealth usability evaluations) on behalf of elderly users.

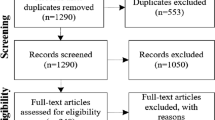

We imported all found papers into JabRef reference manager and removed duplicates (\(n=21\)) (see Fig. 6). We screened title and abstract of the papers based upon their relevance to our defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (\(n=279\)). We excluded 243 papers based on title and abstract review and included the remaining papers (\(n=36\)) in the full text review.

From these 36 papers, we identified 20 papers that reported on applied eHealth usability evaluation methods to elderly users. We also identified 3 further papers by manual search that reported on challenges of eHealth usability evaluation with elderly users. We extracted the following information from these papers:

-

Applied eHealth usability evaluation methods to elderly users (for all 20 papers);

-

Challenges of conducting eHealth usability evaluations with elderly users (if reported in the papers: \(n=6\))

3 Results

We first present the results from the case study, followed by the results of the systematic review. We then derive from both the case study and the systematic review 24 recommendations on how to overcome challenges prior to, during, and after carrying out the eHealth usability evaluation with the elderly.

3.1 Case study

Conduction of the pre-test

Before actual eHealth usability evaluation, a pre-test was conducted with one elderly participant. Implementing a pre-test includes understanding our prospective users and potential challenges arising, while evaluating the usability of eHealth systems. Based on the findings and feedback of the pre-test, the formulated scenario and derived tasks were slightly modified. During the pre-test, we realized that some elderly might not be equipped with a printer at home. Therefore, we modified Task 2 to state that the patient should save the prescription on the computer before sending it to the printer, for instance.

Set-up of eHealth usability evaluation

Conducting the eHealth usability evaluation at the elderly’s homes proved to be useful because elderly felt comfortable in their familiar environment. Elderly users preferred working on their own computers because they are familiar with their own technical equipment. We also recognized that conducting the evaluation “live” is useful, because supervising the elderly with regard to their behavior during the eHealth usability evaluation was necessary (e.g., verbalizing their thoughts, comprehension of tasks). We noted that the elderly are affected by cognitive declines, such as speed of comprehension, which impacted the comprehension of conducting the eHealth usability evaluation. To overcome this challenge, we convinced the elderly and explained to them that they are a great help in finding usability problems.

Procedure of eHealth usability evaluation

It became clear that discussing the procedure of the eHealth usability evaluation with the elderly prior to the start of the eHealth usability evaluation was important because the elderly needed time to adjust to the new situation of conducting the eHealth usability evaluation that was unfamiliar to them. We noted that allocating time for answering questions that the elderly might have was important because the elderly showed interest in the procedure of the eHealth usability evaluation. For instance, the elderly asked questions to clarify concerns, such as privacy concerns. The elderly also showed interest in how personal data was processed during the eHealth usability evaluation.

We recognized that the elderly had difficulties speaking their thoughts out loud because their attention quickly decreased during the evaluation. For this reason, we encouraged the elderly to express their thoughts out loud and asked comprehension questions during the evaluation. We applied brief tasks and recognized that three brief tasks were sufficient because the elderly got tired quickly. Furthermore, we read the tasks out loud because we noticed that this promoted the attention and speed of comprehension of the elderly as to which tasks they should work on. We made no video or audio recordings because the elderly objected the use of recordings due to privacy concerns.

Co-Discovery Evaluation

We invited all seven elderly participants to conduct a Co-Discovery Evaluation as well. The elderly refused to conduct a Co-Discovery Evaluation for a number of reasons. They preferred conducting tasks on their own and emphasized this with statements like “I am old enough to accomplish tasks alone”, “I am an independent person and prefer to struggle through tasks on my own”, or “No thanks. I do not need any help from others”. Furthermore, the elderly confirmed their ability to cope with modern technologies. For example, one elderly emphasized: “Why do I need supervision? I am able to handle a computer myself”. Due to these concerns, we were not able to conduct a Co-Discovery Evaluation with the elderly participants.

Cooperative Usability Testing

We invited all seven elderly participants to conduct Cooperative Usability Testing. All participants refused to conduct Cooperative Usability Testing. They were concerned about the usefulness of video recordings and asked questions like “Why should the evaluation be recorded by video when it is also possible to take notes?” The elderly also had concerns like “I don’t want to see and hear myself twice” or “I do not agree with video recordings because I don’t know where the data really ends up”. Privacy concerns occurred despite precise explanation that personal information would be deleted after completion of the eHealth usability evaluation. Due to these concerns, we were not able to conduct Cooperative Usability Testing with the elderly.

Remote User Testing combined with Think Aloud

All seven participants agreed to attend Remote User Testing combined with Think Aloud. We observed a variety of notable differences in how the elderly interacted with the web-based eHealth intervention. Some participants had problems saving the prescription locally on the computer (see also Table 2). This was not due to poor usability of the web-based eHealth intervention but occurred because the elderly were not familiar enough with the functions of their own computer.

We found usability problems, such as problems concerning the readability of the font size and textual or visual appearance. The most common usability problem was the lack of clarity when entering the received TAN, as it was already pre-filled in light grey font in the input field (Table 4). After the TAN was verified, the description could be downloaded by the elderly (step two, see also Fig. 3). However, the second most common usability problem was that the elderly tried to complete the already pre-filled prescription themselves. The elderly did not understand that the prescription had already been completed by the physician, which made them feel impatient and nervous. The third most common usability problem was that the elderly had difficulties in distinguishing the colorized buttons.

3.2 Systematic review

Applied eHealth usability evaluation methods to elderly

We identified 20 studies that report on applied eHealth usability evaluation methods with elderly participants (Table 5). The majority of the studies applied user-based eHealth usability evaluation methods (18/20), such as Questionnaires, Think Aloud, or Usability Testing. Most of the studies applied Questionnaires as a single or additional eHealth usability evaluation method (14/20). From these mentioned studies applying Questionnaires (\(n=14\)), 11 studies used the System Usability Scale. The second most applied eHealth usability evaluation method was Think Aloud (5/20), followed by Usability Testing (3/20). The minority of the studies applied expert-based eHealth usability evaluation methods, such as Heuristic Evaluation and Cognitive Walkthrough (2/20).

Equal numbers of studies evaluated both eHealth systems (e.g., for health prevention, self care, or activity tracking) (9/20) and mHealth systems (9/20), followed by web-based eHealth systems (4/20). There are studies that conducted an eHealth usability evaluation with two systems, such as mHealth system/eHealth system (1/20) as well as mHealth system/web-based eHealth system (1/20).

Challenges of conducting agile, easily applicable, and useful eHealth usability evaluations with elderly participants

We identified six studies that report on challenges of conducting eHealth usability evaluations with elderly or disabled participants. Table 6 describes four studies that indicate challenges of conducting eHealth usability evaluations with elderly and Table 7 describes two studies that indicate challenges of conducting eHealth usability evaluations with disabled participants. All six studies report on challenges due to cognition, such as that during eHealth usability evaluations elderly or disabled participants easily lose their attention and their concentration, or did not sufficiently speak their thoughts out loud. One study reports on challenges due to motivation, such as that the elderly learn a new system more easily if they are supported by a mentor. Challenges due to perception were also reported in one study, such as that the elderly had difficulties in recognizing the font size of a text needed to accomplish the tasks during an eHealth usability evaluation. Finally, one study reported on challenges due to physical abilities, such as difficulties with the finger-based input necessary to accomplish the tasks during eHealth usability evaluations.

3.3 Recommendations derived from both the case study and systematic review

Recommendations on how to deal with challenges prior to, during, and after carrying out the eHealth usability evaluation with elderly participants

From the case study and the systematic review, we formulated 24 recommendations to address challenges prior to, during, and after carrying out the eHealth usability evaluation with elderly participants (see Table 8). We categorize the challenges according to the stage of software lifecycle (requirements engineering, design, and evaluation), taking into account the stage that follows the eHealth usability evaluation. We then related the recommendations to age-related barriers (cognition, motivation, perception, and physical abilities). The recommendations originate equally from the results of the case study and systematic review (in both cases 15). Some of these recommendations derived from the case study are also supported by the literature (6/15). For example, our recommendation to encourage elderly participants to speak their thoughts out loud originates from our case study that is also confirmed by the literature. Two recommendations for the requirements engineering stage of the software lifecycle were derived (2/24). We formulated three recommendations in both cases—for the design stage of software lifecycle and for the stage that follows the eHealth usability evaluation—that are supported by literature (3/24). In total, 16 recommendations could be derived specifically for the evaluation stage of software lifecycle. From these 16 recommendations, we defined the most recommendations for motivation (8/16), the second most recommendations for cognition (5/16), the third most recommendations for physical abilities (2/16), and the fewest recommendations for perception (1/16).

4 Discussion

We aimed to examine the following research questions: (1) Which eHealth usability evaluation methods are applicable to evaluate eHealth interventions with elderly users?, (2) What challenges might be encountered when conducting an agile, easily applicable, and useful eHealth usability evaluation with elderly users?, and (3) How to deal with and overcome these challenges that arise prior to, during, and after carrying out the eHealth usability evaluation conducted with elderly users?

Our first research question aimed to identify which eHealth usability evaluation methods are applicable to evaluate eHealth interventions with elderly users. Our findings show that Remote User Testing combined with Think Aloud could be successfully applied to evaluate the web-based eHealth intervention with elderly users. Co-Discovery Learning and Cooperative Usability Testing were found not to be suitable for conducting the eHealth usability evaluation with elderly users. We found that there are eHealth usability evaluation methods that are not applicable in their current version with elderly users. These include Co-Discovery Evaluation, Cooperative Usability Testing, Retrospective eHealth usability evaluation methods, and Think Aloud. Some of these eHealth usability evaluation methods can be useful if they are evolved and adapted to meet the challenges of conducting eHealth usability evaluations with elderly participants.

Research has proposed the Peer Discovery usability evaluation method as a modified version for user-based eHealth usability evaluations, taking into consideration Think Aloud, which allows the elderly to complete the tasks of the eHealth usability evaluation together with a caregiver or a family member taking part in the eHealth usability evaluation to make the elderly participant feel more comfortable [40]. Research further suggests the eHealth usability evaluation method Peer Community Sessions, where eHealth interventions are evaluated by a group of elderly participants [40]. We cannot confirm these suggestions on conducting an eHealth usability evaluation with a caregiver or family member or on elderly participant working in groups because the elderly in our study refused to work with peers or to involve a family member. Our results showed that the elderly are willing and able to perform tasks on their own.

In the course of our research, Remote User Testing combined with Think Aloud proved to be suitable with elderly, although research showed that there is a lack of existing guidelines available for Remote User Testing with elderly users [42]. In our study, we conducted the Remote User Testing in a modified version bringing together the elderly at their homes with the software developers via video conference in the eHealth usability evaluation. The application of a modified version is confirmed in the literature, which states that Remote User Testing must be adapted to and tested with elderly participants [42]. We observed and thus recommend that carrying out the eHealth usability evaluation with elderly users “live” at the their homes using brief tasks is one possibility to overcome challenges.

Our second research question addressed what challenges might be encountered when conducting an agile, easily applicable, and useful eHealth usability evaluation with elderly users. The results show that challenges due to motivational, cognitive, or physical decline of elderly users were identified. For instance the identified challenges due to cognitive decline, can result in limited verbalization skills, reduced attention, or speed of comprehension. Technology should be accessible and usable [73] which confirms our findings that declines due to cognition, motivation, perception, and physical abilities of elderly users need to be considered. Our results show further that the majority of the studies applied Questionnaires as a single or additional eHealth usability evaluation method with elderly users. Half of the studies applied the System Usability Scale as Questionnaire. However, recent research has shown that the System Usability Scale is an inadequate stand-alone eHealth usability evaluation method [19]. Further, Questionnaires were criticized due to their complex scoring system [39] and their non-suitability for elderly [11]. No particularities were found with regard to the setting of the studies because research on applying eHealth usability evaluations with elderly is conducted equally often in Europe and outside of Europe.

During the eHealth usability evaluation, we recognized that the elderly struggled to speak their thoughts out loud and to keep their focus on accomplishing the tasks. We observed different concerns of the elderly that encompassed, for example, privacy concerns and the understanding (concerning Co-Discovery Learning) of why a joint evaluation with another participant should be beneficial. We focused our study on identifying challenges for conducting eHealth usability evaluation with the elderly because their ability to use modern technologies is important so that they do not lose touch with society [74]. This coincides with the concept of universal usability in the course of which the design of technologies encompasses the needs of different prospective users [75]. Universal design aims at considering special needs of the elderly and disabled users [76, 77]. This has resonance with research that suggests the need of inclusive design for universal access [78].

Our third research question addressed ways to deal with and overcome these challenges that arise prior to, during, and after carrying out the eHealth usability evaluation conducted with elderly users. We formulated 24 recommendations to address and overcome these challenges that arise prior to, during, and after carrying out the eHealth usability evaluation with elderly users. Our recommendations facilitate accessibility, acceptability, and usability of information technology, such as eHealth systems, for elderly users. We related our recommendations to the stages of the software lifecycle (requirements engineering, design, and evaluation), as not only acceptability has become one of the most important aspects of healthcare interventions design, evaluation, and implementation [79]. Indeed, in line with [80], our results confirm that accessibility as well as usability must be considered in early stages of software lifecycle, such as the design stage.

We structured the recommendations also according to age-related barriers into cognition, motivation, perception, and physical abilities to address age-related declines of the elderly. Research has shown that for universal participation, considering the two aspects of accessibility and usability is crucial [81]. In terms of accessibility of technology, more generally universal access to technology, we must consider that the interaction between human and computer is characterized by signal as well as sign processes. Considering these sign processes, the technical semiotics, is fundamental to the understanding of Human-Computer Interaction [82].

Recent research has shown that most systematic literature reviews address usability as it relates to elderly users [83]. This illustrates the need to conduct a case study and likewise the fact that most of our recommendations are based on the case study findings. Although the idea of universal usability has been addressed by various studies [75, 84], it is obvious that there is still a lack of contributions implementing case studies to investigate challenges of elderly users in making eHealth systems accessible, acceptable, and usable for the information society.

Limitations

We originally intended to apply all three chosen eHealth usability evaluation methods with the elderly. However, we observed that the elderly refused to participate in Co-Discovery Evaluation and Cooperative Usability Testing. Nevertheless, we were able to propose 24 recommendations from the case study together with the results of the systematic review. Conducting the case study with one eHealth usability evaluation method, Remote User Testing with Think Aloud, presents a disadvantage that indicates a difficulty in generalizing the results. We invited all seven elderly patients to attend the eHealth usability evaluation with each chosen eHealth usability evaluation method. Despite the small number of participants (\(n=7\)), we reached a thematic saturation after conducting the eHealth usability evaluation with four elderly users because the usability problems found were repeated. However, we cannot assume that we have found all possible usability problems. To generalize our results, it is essential to validate these findings with more elderly participants and a different eHealth intervention. During eHealth usability evaluation, the elderly objected to the use of video recordings due to privacy concerns. However, additional video recordings would have been helpful to facilitate the comprehension as to why some usability problems may have occurred.

To accomplish the systematic literature review, we selected four databases (ACM Digital Library, Cochrane Library, IEEE Xplore, and Medline) that were relevant to the thematic field of our systematic review. A disadvantage of selecting these four databases that catalog peer-reviewed literature (except conference papers) is that we may have missed relevant papers within gray literature. We included papers that report on experiences such as challenges, applicability, acceptability, or feasibility of applied eHealth usability evaluation methods to elderly. Since experiences on challenges, applicability, acceptability, or feasibility of applied eHealth usability evaluation methods for elderly users may be mentioned as a side result in research, we cannot assume to have found all possible relevant experiences. We excluded papers that were published before 2012 because we focused on the most recent results. Our results showed that half of the identified studies on applied eHealth usability evaluations with elderly were published in the last three years. However, it may be possible that we have missed relevant papers from the years before 2012. We also included findings on reported challenges with disabled participants because we did not want to exclude possible further relevant information from this related field. However, it is not possible to generalize the results, as only a small number of studies (\(n=2\)) are involved.

From both the case study and the systematic review, we derived recommendations on how to overcome challenges prior to, during, and after carrying out the eHealth usability evaluations with elderly participants. No contradictions could be identified between the results of the case study and the systematic review; however, contradictions cannot completely be excluded.

Future research

We found that established eHealth usability evaluation methods such as Co-Discovery Evaluation, Cooperative Usability Testing, and Think Aloud cannot be used in their original version. These eHealth usability evaluation methods need to be modified to be useful for evaluating eHealth systems with elderly participants. This illustrates that there is a need to explore and propose evolved versions of well-established eHealth usability evaluation methods that had been adapted to accomplish agile, easily applicable, and useful eHealth usability evaluations with elderly users. It is important to further explore how elderly persons who suffer from age-related barriers such as cognition, motivation, perception, or physical abilities behave during eHealth usability evaluation.

Furthermore, future research is needed to facilitate the selection of an appropriate eHealth usability evaluation method. In a subsequent study, the authors aim to develop a decision aid valuable for guiding the choice of a suitable eHealth usability evaluation method.

5 Conclusion

A systematic literature review conducted subsequently to the case study unveiled that there are eHealth usability evaluation methods that are unsuitable for implementing an agile, easily applicable, and useful eHealth usability evaluation with elderly participants. Based on our findings from the case study and the systematic review, we derived recommendations on how to deal with challenges prior to, during, and after applying eHealth usability evaluation methods with elderly users and how these challenges can be overcome. The majority of our proposed recommendations to facilitate eHealth usability evaluation relate to challenges concerning cognition and motivation. We found that established eHealth usability evaluation methods will require modification to be useful for evaluating eHealth systems with elderly participants. Our insights may encourage future studies on eHealth usability evaluation with elderly users. The recommendations contribute to improving the accessibility, acceptability, and usability of eHealth interventions by the elderly.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study is not publicly available to protect participants privacy.

References

Garcia, A.C., de Lara, S.M.A.: Enabling aid in remote care for elderly people via mobile devices: the MobiCare case study. In: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Software Development and Technologies for Enhancing Accessibility and Fighting Info-exclusion, DSAI 2018, Thessaloniki, Greece, pp. 270–277 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1145/3218585.3218671

Wildenbos, G.A., Jaspers, M.W.M., Schijven, M.P., Dusseljee-Peute, L.W.: Mobile health for older adult patients: using an aging barriers framework to classify usability problems. Int. J. Med. Inform. 124, 68–77 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.01.006

Eslami, M.Z., Zarghami, A., van Sinderen, M., Wieringa, R.: Care-giver tailoring of IT-based healthcare services for elderly at home: a field test and its results. In: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, PervasiveHealth 2013, Venice, Italy, pp. 216–223 (2013). https://doi.org/10.4108/icst.pervasivehealth.2013.251931

McGarrigle, L., Todd, C.: Promotion of physical activity in older people using mHealth and eHealth technologies: rapid review of reviews. J. Med. Internet Res. 22(12), e22201 (2020). https://doi.org/10.2196/22201

Steinert, A., Haesner, M., Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.: Activity-tracking devices for older adults: comparison and preferences. Univ. Access Inform. Soc. 17(2), 411–419 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-017-0539-7

Gentry, M.T., Lapid, M.I., Rummans, T.A.: Geriatric telepsychiatry: systematic review and policy considerations. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 27(2), 109–127 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2018.10.009

Góngora Alonso, S., Hamrioui, S., de la Torre Díez, I., Cruz, E.M., López-Coronado, M., Franco, M.: Social robots for people with aging and dementia: a systematic review of literature. Telemed. e-Health 25(7), 533–540 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2018.0051

Batsis, J.A., DiMilia, P.R., Seo, L.M., Fortuna, K.L., Kennedy, M.A., Blunt, H.B., Bagley, P.J., Brooks, J., Brooks, E., Kim, S.Y., Masutani, R.K., Bruce, M.L., Bartels, S.J.: Effectiveness of ambulatory telemedicine care in older adults: a systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 67(8), 1737–1749 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15959

Wildenbos, G.A., Peute, L.W., Jaspers, M.W.M.: A framework for evaluating mHealth tools for older patients on usability. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 210, 783–787 (2015). https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-512-8-783

Lum, A.S.L., Chiew, T.K., Ng, C.J., Lee, Y.K., Lee, P.Y., Teo, C.H.: Development of a web-based insulin decision aid for the elderly: usability barriers and guidelines. Univ. Access Inform. Soc. 16(3), 775–791 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-016-0503-y

Isaković, M., Sedlar, U., Volk, M., Bešter, J.: Usability pitfalls of diabetes mHealth apps for the elderly. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 1–9 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1604609

Yerrakalva, D., Yerrakalva, D., Hajna, S., Griffin, S.: Effects of mobile health app interventions on sedentary time, physical activity, and fitness in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 21(11), e14343 (2019). https://doi.org/10.2196/14343

Kampmeijer, R., Pavlova, M., Tambor, M., Golinowska, S., Groot, W.: The use of e-health and m-health tools in health promotion and primary prevention among older adults: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 16(S5), 467–479 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1522-3

Hoffman, A.S., Bateman, D.R., Ganoe, C., Punjasthitkul, S., Das, A.K., Hoffman, D.B., Housten, A.J., Peirce, H.A., Dreyer, L., Tang, C., Bennett, A., Bartels, S.J.: Development and field testing of a long-term care decision aid website for older adults: engaging patients and caregivers in user-centered design. Gerontologist 60(5), 935–946 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz141

Taylor, M.J., Stables, R., Matata, B., Lisboa, P.J.G., Laws, A., Almond, P.: Website design: technical, social and medical issues for self-reporting by elderly patients. J. Health Inform. 20(2), 136–150 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458213488382

Guo, F., Chen, J., Li, M., Lyu, W., Zhang, J.: Effects of visual complexity on user search behavior and satisfaction: an eye-tracking study of mobile news apps. Univ. Access Inform. Soc. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-021-00815-1

Ishaq, A., Shoaib, M.: A smartphone application for enhancing educational skills to support and improve the safety of autistic individuals. Univ. Access Inform. Soc. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-021-00817-z

Pancar, T., Yildirim, S.O.: Exploring factors affecting consumers adoption of wearable devices to track health data. Univ. Access Inform. Soc. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-021-00848-6

Broekhuis, M., van Velsen, L., Hermens, H.: Assessing usability of eHealth technology: a comparison of usability benchmarking instruments. Int. J. Med. Inform. 128, 24–31 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.05.001

Alajarmeh, N.: Evaluating the accessibility of public health websites: an exploratory cross-country study. Univ. Access Inform. Soc. 21, 771–789 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-020-00788-7

Henry, S.L.: Introduction to web accessibility. https://www.w3.org/WAI/fundamentals/accessibility-intro/ (2021). Accessed 6 Dec 2021

Agrawal, G., Kumar, D., Singh, M.: Assessing the usability, accessibility, and mobile readiness of e-government websites: a case study in India. Univ. Access Inform. Soc. 21, 737–748 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-021-00800-8

Madeira, S., Branco, F., Gonçalves, R., Au-Yong-Oliveira, M., Moreira, F., Martins, J.: Accessibility of mobile applications for tourism—is equal access a reality? Univ. Access Inform. Soc. 20, 555–571 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-020-00770-3

Böhm, S.: Do you know your user group? Why it is essential to put your user-requirements analysis on a broad database. Univ. Access Inform. Soc. 21, 909–926 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-021-00805-3

Nielsen, J.: Usability 101: introduction to usability. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/ (2012). Accessed 6 Dec 2021

Zareei, H., Yusuff, R.M., Salit, S.M., S Norazizan, S.A.R., Hussain-Mohd, R.: Assessing the usability and ergonomic considerations on communication technology for older Malaysians. Univ. Access Inform. Soc. 16(2), 425–433 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-016-0470-3

Yazdi, F., Vieritz, H., Jazdi, N., Schilberg, D., Göhner, P., Jeschke, S.: A concept for user-centered development of accessible user interfaces for industrial automation systems and web applications. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference, UAHCI 2011 held as part of HCI International 2011, Orlando, FL, USA, pp. 301–310 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-21657-2_32

Moran, K.: Usability Testing 101. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-testing-101/ (2019). Accessed 7 Dec 2021

Jaspers, M.W.M.: A comparison of usability methods for testing interactive health technologies: methodological aspects and empirical evidence. Int. J. Med. Inform. 78(5), 340–353 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.10.002

Hussain, Z., Slany, W., Holzinger, A.: Current state of agile user-centered design: a survey. In: Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the Workgroup Human–Computer Interaction and Usability Engineering of the Austrian Computer Society, USAB 2009, Linz, Austria, pp. 416–427 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-10308-7_30

Hussain, Z., Slany, W., Holzinger, A.: Investigating agile user-centered design in practice: a grounded theory perspective. In: Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the Workgroup Human–Computer Interaction and Usability Engineering of the Austrian Computer Society, USAB 2009, Linz, Austria, pp. 279–289 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-10308-7_19

Palacio, R.R., Acosta, C.O., Cortez, J., Morán, A.L.: Usability perception of different video game devices in elderly users. Univ. Access Inform. Soc. 16(1), 103–113 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-015-0435-y

Baravalle, A., Lanfranchi, V.: Remote web usability testing. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 35(3), 364–368 (2003). https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03195512

Kellar, M., Hawkey, K., Inkpen, K.M., Watters, C.: Challenges of capturing natural web-based user behaviors. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Int. 24(4), 385–409 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1080/10447310801973739

Bastien, J.M.C.: Usability testing: a review of some methodological and technical aspects of the method. Int. J. Med. Inform. 79(4), e18–e23 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.12.004

Wozney, L.M., Baxter, P., Fast, H., Cleghorn, L., Hundert, A.S., Newton, A.S.: Sociotechnical human factors involved in remote online usability testing of two eHealth interventions. JMIR Hum. Factors 3(1), e6 (2016). https://doi.org/10.2196/humanfactors.4602

Wildenbos, G.A., Peute, L., Jaspers, M.: Aging barriers influencing mobile health usability for older adults: a literature based framework (MOLD-US). Int. J. Med. Inform. 114, 66–75 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.03.012

Sinabell, I., Ammenwerth, E.: ToUsE: Toolbox for eHealth Usability Evaluations. UMIT TIROL, Hall in Tirol (2022). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.31458.61125

Sinabell, I., Ammenwerth, E.: Agile, easily applicable, and useful eHealth usability evaluations: systematic review and expert-validation. Appl. Clin. Inform. 13(01), 67–79 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1740919

Wildenbos, G.A. Design speaks: improving patient-centeredness for older people in a digitalizing healthcare context. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands (2019)

Frøkjær, E., Hornbæk, K.: Cooperative usability testing: complementing usability tests with user-supported interpretation sessions. In: Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2005, Portland, OR, USA, pp. 1383–1386 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1145/1056808.1056922

Hill, J.R., Brown, J.C., Campbell, N.L., Holden, R.J.: Usability-in-place-remote usability testing methods for homebound older adults: rapid literature review. JMIR Form. Res. 5(11), e26181 (2021). https://doi.org/10.2196/26181

Downey, L.L.: Group usability testing: evolution in usability techniques. J. Usability Stud. 2(3), 133–144 (2007)

Nielsen, J.: Why you only need to test with 5 users. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/why-you-only-need-to-test-with-5-users/ (2000). Accessed 8 Feb 2022

Jonker, L.T., Plas, M., de Bock, G.H., Buskens, E., van Leeuwen, B.L., Lahr, M.M.H.: Remote home monitoring for older surgical cancer patients: perspective on study implementation and feasibility. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 28, 67–78 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-08705-1

Alonso, S.G., Guzmán, J.M.T., de Abajo, B.S., Sánchez, J.L.M., Martín, M.F., de la Torre Díez, I.: Usability evaluation of the eHealth Long Lasting Memories program in Spanish elderly people. Health Inform. J. 26(3), 1728–1741 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458219889501

Balsa, J., Félix, I., Cláudio, A.P., Carmo, M.B., Costa e Silva, I., Guerreiro, A., Guedes, M., Henriques, A., Guerreiro, M.P.: Usability of an intelligent virtual assistant for promoting behavior change and self-care in older people with type 2 diabetes. J. Med. Syst. 44, 130 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-020-01583-w

Bergquist, R., Vereijken, B., Mellone, S., Corzani, M., Helbostad, J.L., Taraldsen, K.: App-based self-administrable clinical tests of physical function: development and usability study. JMIR mhealth uhealth 8(4), e16507 (2020)

Kim, H.H., Lee, S., Cho, N., You, H., Choi, T., Kim, J.: User-dependent usability and feasibility of a swallowing training mHealth app for older adults: mixed methods pilot study. JMIR mhealth uhealth 8(7), e19585 (2020)

Petersen, C.L., Minor, C.M., Mohieldin, S., Park, L.G., Halter, R.J., Batsis, J.A.: Remote rehabilitation: a field-based feasibility study of an mHealth resistance exercise band. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM International Conference on Connected Health: Applications, Systems and Engineering Technologies, HRI 2020, Cambridge, United Kingdom, pp. 5–6 (2020)

Macis, S., Loi, D., Ulgheri, A., Pani, D., Solinas, G., La Manna, S., Cestone, V., Guerri, D., Raffo, L.: Design and usability assessment of a multi-device SOA-based telecare framework for the elderly. IEEE J. Biomed. 24(1), 268–279 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2019.2894552

Santana-Mancilla, P.C., Anido-Rifón, L.E., Contreras-Castillo, J., Buenrostro-Mariscal, R.: Heuristic evaluation of an IOMT system for remote health monitoring in senior care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(5), 1586 (2020)

Holden, R.J., Campbell, N.L., Abebe, E., Clark, D.O., Ferguson, D., Bodke, K., Boustani, M.A., Callahan, C.M.: Usability and feasibility of consumer-facing technology to reduce unsafe medication use by older adults. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 16(1), 254–61 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.02.011

Quintana, Y., Fahy, D., Abdelfattah, A.M., Henao, J., Safran, C.: The design and methodology of a usability protocol for the management of medications by families for aging older adults. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 19, 181 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-019-0907-8

Bolle, S., Romijn, G., Smets, E.M.A., Loos, E.F., Kunneman, M., van Weert, J.C.M.: Older cancer patients’ user experiences with web-based health information tools: a think-aloud study. J. Medical Internet Res. 18(7), 1–17 (2016). https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5618

Jiménez-Fernández, S., de Toledo, P., del Pozo, F.: Usability and interoperability in wireless sensor networks for patient telemonitoring in chronic disease management. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 60(12), 3331–3339 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2013.2280967

Olsson, A., Engström, M., Lampic, C., Skovdahl, K.: A passive positioning alarm used by persons with dementia and their spouses—a qualitative intervention study. BMC Geriatr. 13(11), 1–9 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-13-11

Nayak, L., Priest, L., Stuart-Hamilton, I., White, A.: Website design attributes for retrieving health information by older adults: an application of architectural criteria. Univ. Access Inform. Soc. 5(2), 170–179 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-006-0029-9

Springett, M., Mihajlov, M., Brzovska, E., Orozel, M., Elsner, V., Oppl, S., Stary, C., Keith, S., Richardson, J.: An analysis of social interaction between novice older adults when learning gesture-based skills through simple digital games. Univ. Access Inform. Soc. 21, 639–655 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-021-00793-4

Fan, M, Zhao, Q., Tibdewal, V.: Older adults’ think-aloud verbalizations and speech features for identifying user experience problems. In: Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CH 2021, Yokohama, Japan, pp. 1–13 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445680

Chandrashekar, S., Stockman, T., Fels, D., Benedyk, R.: Using think aloud protocol with blind users: a case for inclusive usability evaluation methods. In: Proceedings of the 8th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, ASSETS 2006, Portland, Oregon, USA, pp. 251–252 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1145/1168987.1169040

Petrie, H., Hamilton, F., King, N., Pavan, P.: Remote usability evaluations with disabled people. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2006, Montréal, Québec, Canada, pp. 1133–1141 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1145/1124772.1124942

Parke, B., Hunter, K.F., Beryl Marck, P.: A novel visual method for studying complex health transitions for older people living with dementia. Int. J. Qual. Methods (2015). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915614150

Silva, A., Martins, A.I., Caravau, H., Almeida, A.M., Silva, T., Ribeiro, Ó., Santinha, G., Rocha, N.: Experts evaluation of usability for digital solutions directed at older adults: a scoping review of reviews. In: Proceedings of 9th International Conference on Software Development and Technologies for Enhancing Accessibility and Fighting Info-exclusion, DSAI 2020, Online Portugal, pp. 174–181 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1145/3439231.3439238

Stuck, R.E., Chong, A.W., Mitzner, T.L., Rogers, W.A.: Medication management apps: usable by older adults? Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 61(1), 1141–1144 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1177/1541931213601769

Harrington, C.N., Ruzic, L., Sanford, J.A.: Universally accessible mHealth apps for older adults: towards increasing adoption and sustained engagement. In: 11th International Conference, UAHCI 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada, pp. 3–12 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58700-4_1

Holzinger, A., Searle, G., Kleinberger, T., Seffah, A., Javahery, H.: Investigating usability metrics for the design and development of applications for the elderly. In: Proceedings of 11th International Conference on Computers for Handicapped Persons, ICCHP 2008, Linz, Austria, pp. 98–105 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-70540-6_13

Demiris, G., Finkelstein, S.M., Speedie, S.M.: Considerations for the design of a web-based clinical monitoring and educational system for elderly patients. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 8(5), 468–472 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1136/jamia.2001.0080468

Engelsma, T., Jaspers, M.W.M., Peute, L.W.: Considerate mHealth design for older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD): a scoping review on usability barriers and design suggestions. Int. J. Med. Inform. 152, 104494 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104494

Barnard, Y., Bradley, M.D., Hodgson, F., Lloyd, A.D.: Learning to use new technologies by older adults: perceived difficulties, experimentation behaviour and usability. Comput. Hum. Behav. 29(4), 1715–1724 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.006

Ahmad, N.A., Razak, F.H.A., Zainal, A., Kahar, S., Adnan, W.A.W.: Teaching older people using web technology: a case study. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Computer Science Applications and Technologies, ACSAT 2013, Kuching, Malaysia, pp. 396–400 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1109/ACSAT.2013.84

Barbosa Neves, B., Franz, R.L., Munteanu, C., Baecker, R., Ngo, M.: “My Hand Doesn’t Listen to Me!”: adoption and evaluation of a communication technology for the ‘Oldest Old’. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2015, Seoul, South Korea, pp. 1593–1602 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702430

Leahy, D., Dolan, D.: Digital literacy—is it necessary for eInclusion? In: Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the Workgroup Human–Computer Interaction and Usability Engineering of the Austrian Computer Society, USAB 2009, Linz, Austria, pp. 149–158 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-10308-7_10

Lindberg, R.S.N., de Troyer, O.: Towards an up to date list of design guidelines for elderly users. In: Proceedings of the 1st International SIGHI-Conference, CHI Greece 2021, Athens, Greece, pp. 1–7 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3489410.3489418

Vanderheiden, G.: Fundamental principles and priority setting for universal usability. In: Proceedings on the Conference on Universal Usability, CUU 2000, Arlington, VA, USA, pp. 32–38 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1145/355460.355469

Stephanidis, C., Akoumianakis, D.: Universal design: towards universal access in the Information Society, CHI 2001, Seattle, WA, USA, pp. 499–500 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1145/634067.634352

Nunes, F., Kerwin, M., Silva, P.A.: Design recommendations for TV user interfaces for older adults: findings from the eCAALYX project. In: Proceedings of the 14th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, ASSETS 2012, Boulder, CO, USA, pp. 41–48 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1145/2384916.2384924

Chalamandaris, A., Raptis, S., Tsiakoulis, P., Karabetsos, S.: Enhancing accessibility of web content for the print-impaired and blind people. In: Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the Workgroup Human–Computer Interaction and Usability Engineering of the Austrian Computer Society, USAB 2009, Linz, Austria, pp. 249–263 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-10308-7_17

Sekhon, M., Cartwright, M., Francis, J.J.: Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17(88), 1–13 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

Mori, G., Buzzi, M.C., Buzzi, M., Leporini, B., Penichet, V.M.R.: Collaborative editing for all: the Google Docs example. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference, UAHCI 2011 held as part of HCI International 2011, Orlando, FL, USA, pp. 165–174 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-21657-2_18

Senette, C., Buzzi, M.C., Buzzi, M., Leporini, B.: Enhancing Wikipedia editing with WAI-ARIA. In: Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the Workgroup Human–Computer Interaction and Usability Engineering of the Austrian Computer Society, USAB 2009, Linz, Austria, pp. 159–177 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-10308-7_11

Holzinger, A., Searle, G., Auinger, A., Ziefle, M.: Informatics as semiotics engineering: lessons learned from design, development and evaluation of ambient assisted living applications for elderly people. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference, UAHCI 2011 held as part of HCI International 2011, Orlando, FL, USA, pp. 183–192 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-21666-4_21

Bastardo, R., Pavão, J., Rocha, N.P.: User-centred usability evaluation of embodied communication agents to support older adults: a scoping review. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology & Systems, ICITS 2022, Xiamen, Fujian, China, pp. 509–518 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96293-7_42

Marcus, A.: Universal, ubiquitous, user-interface design for the disabled and elderly. Interactions 10(2), 23–27 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1145/637848.637858

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge that Medi-Prime, a company in the field of eHealth, provided us with the web-based eHealth intervention necessary to conduct this study. We further thank the participants, all of whom contributed greatly to this study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by UMIT TIROL-Private Universität für Gesundheitswissenschaften und -technologie GmbH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sinabell, I., Ammenwerth, E. Challenges and recommendations for eHealth usability evaluation with elderly users: systematic review and case study. Univ Access Inf Soc 23, 455–474 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-022-00949-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-022-00949-w