Abstract

Objectives

We analyze the impact of the positioning of shifts (morning, afternoon, night) on worker absenteeism in a large German automobile plant.

Methods

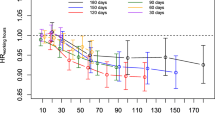

Using a completely balanced panel of 153 organizational units over the 2-year-period 2009 to 2010 (i.e. 104 consecutive weeks with 15,912 unit-week-observations) we estimate a series of GLM and Fixed Effects models.

Results

Our main finding is that during afternoon shifts absence rates are significantly higher than during either morning or night shifts and that absence rates are particularly high during the afternoon shift immediately following the 3 weeks of consecutive night shifts. We attribute our first finding to the “social opportunity costs” of working and the second one to a “tax evasion effect”.

Conclusions

When designing new shift models, firms should try to anticipate their workers’ reaction to avoid unintended incentives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data is proprietary and can, therefore, not be made available to other researchers.

Notes

In Germany, workers do not have to present a doctor’s certificate stating that they are unable to come to work for absence spells shorter than 3 days.

The collective bargaining agreements the company had signed with IG Metall stipulated that the compensation for working late hours is monetary and not in the form of days off.

The night shift premium in our particular case was 30% of hourly wages for the time between 8:00 pm and midnight, 45% for the time between midnight and 4:00 am and 30% for the time between 4:00 and 6:00 am [32]. This implies that not only night shifts (10:30 pm–6:30 am) were subject to a premium but also—to a lower extent—late shifts (in the time between 8:00 and 10:30 pm).

The German income tax act states that premiums of up to 25% of hourly wages for working late hours (8:00 pm–6:00 am) are exempt from income tax. Additionally, for the time between midnight and 4:00 am night work premiums of up to 40% of hourly wages are exempt from income tax.

The calculation of the monetary incentive to postpone a sickness spell is based on the average annual income of production workers in the company, the average income tax rate and the premium paid during the respective shift.

Detailed results are available from the authors upon request.

The difficulties of implementing field experiments in firms are discussed in Bandiera et al. [7]. Some of the most widely cited studies in this tradition (e.g. [6, 42] also fail to estimate difference-in-difference models as they also lack randomly selected control groups of workers for whom no change in the institutional setting was implemented.

The results are stable upon changes in the reference group.

The night work premium is a mandatory legal requirement in Germany [5]. However, the exact amount of the premium is specified in binding collective bargaining agreements.

In Germany, most employees are by law entitled to 6 weeks of sick pay covered by the employer.

The only exception here is the second night shift week (week 8) as it has significantly lower absence rates compared to all other weeks. This result remains puzzling and further analysis is required to identify the (potential) causes of this effect.

A major shortcoming of our data is—as already mentioned above—the lack of information on the age, gender, subjective health conditions and family obligations of the different team members. This is an issue insofar as Jacobsen and Fjeldbraaten [33] show that it is not shiftwork per se that is associated with worker absenteeism. Instead, there is an indirect effect particularly through work-life-conflict and perceived health.

References

Abu Farha, R., Alefishal, E.: Shift work and the risk of cardiovascular diseases and metabolic syndrome among Jordanian employees. Oman Med. J. 33(3), 235–242 (2018)

Åkerstedt, T.: Psychological and psychophysiological effects of shift work. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 16(1), 67–73 (1990)

Åkerstedt, T.: Shift work and disturbed sleep/wakefulness. Occup. Med. 53(2), 89–94 (2003)

Angersbach, D., Knauth, P., Loskant, H., Karvonen, M.J., Undeutsch, K., Rutenfranz, J.: A retrospective cohort study comparing complaints and diseases in day and shiftworkers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 45(2), 127–140 (1980)

Arbeitszeitgesetz (ArbZG, Working Time Act): § 6 Nacht und Schichtarbeit. Arbeitszeitgesetz vom 6. Juni 1994 (BGBl. I S. 1170, 1171), das zuletzt durch Artikel 3 Absatz 6 des Gesetzes vom 20. April 2013 (BGBl. I S. 868) geändert worden ist, https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bundesrecht/arbzg/gesamt.pdf (1994). Accessed 25 Oct 2014

Bandiera, O., Barankay, I., Rasul, I.: Social preferences and the response to incentives: evidence from personnel data. Q. J. Econ. 120(3), 917–962 (2005)

Bandiera, O., Barankay, I., Rasul, I.: Field experiments with firms. J. Econ. Perspect. 25(3), 63–82 (2011)

Barton, J., Folkard, S.: Advancing versus delaying shift systems. Ergonomics 36(1–3), 59–64 (1993)

Bloom, N., Eifert, B., Mahajan, A., McKenzie, D., Roberts, J.: Does management matter? Evidence from India. Q. J. Econ. 128(1), 1–51 (2013)

Böckerman, P., Laukkanen, E.: What makes you work while you are sick? Evidence from a survey of workers. Eur. J. Public Health 20(1), 43–46 (2010)

Böckerman, P., Bryson, A., Ilmakunnas, P.: Does high involvement management improve worker wellbeing? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 84(2), 660–680 (2012)

Bøggild, H., Knutsson, A.: Shift work, risk factors and cardiovascular disease. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 25(2), 85–99 (1999)

Bourbonnais, R., Vinet, A., Vézina, M., Gingras, S.: Certified sick leave as a non-specific morbidity indicator: a case-referent study among nurses. Br. J. Ind. Med. 49(10), 673–678 (1992)

Broström, G., Johansson, P., Palme, M.: Economic incentives and gender differences in work absence behavior. Swed. Econ. Policy Rev. 11, 33–63 (2004)

Canuto, R., Garcez, A.S., Olinto, M.T.A.: Metabolic syndrome and shift work: a systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 17(6), 425–431 (2013)

Catano, V.M., Bissonnette, A.B.: Examining paid sickness absence by shift workers. Occup. Med. 64(4), 287–293 (2014)

Costa, G.: Shift work and occupational medicine: an overview. Occup. Med. 53(2), 83–88 (2003)

Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD): Free climate data online. ftp://opendata.dwd.de/climate_environment/CDC/regional_averages_DE/monthly/air_temperature_mean/ (2014). Accessed 20 Aug 2020

Drake, C.L., Roehrs, T., Richardson, G., Walsh, J.K., Roth, T.: Shift Work sleep disorder: prevalence and consequences beyond that of symptomatic day workers. Sleep 27(8), 1453–1462 (2004)

Einkommensteuergesetz (EStG, Income Tax Act): §3b Steuerfreiheit von Zuschlägen für Sonntags-, Feiertags- oder Nachtarbeit. Einkommensteuergesetz in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 8. Oktober 2009 (BGBl. I S. 3366, 3862), zuletzt durch Artikel 3 des Gesetzes vom 25. Juli 2014 (BGBl. I S. 1266) geändert. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/estg (2009). Accessed 20 Aug 2020

Eriksen, W., Bruusgaard, D., Knardahl, S.: Work factors as predictors of sickness absence: a three month prospective study of nurses’ aides. Occup. Environ. Med. 60(4), 271–278 (2003)

Esquirol, Y., Bongard, V., Mabile, L., Jonnier, B., Soulat, J.-M., Perret, B.: Shift work and metabolic syndrome: respective impacts of job strain, physical activity, and dietary rhythms. Chronobiol. Int. J. Biol Med Rhythm Res 26(3), 544–559 (2009)

Eurofound: Fifth European working conditions survey. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg (2012)

Folkard, S., Tucker, P.: Shift work, safety and productivity. In-depth review: shift work. Occup. Med. 53(2), 95–101 (2003)

Frick, B., Simmons, R., Stein, F.: The cost of shiftwork: absenteeism in a large german automobile plant. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 32, 236–256 (2018)

Frick, B., Götzen, U., Simmons, R.: The hidden costs of high-performance work practices: evidence from a large german steel company. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 66(1), 198–224 (2013)

Grosswald, B.: Shift work and negative work-to-family spillover. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 30(4), 31–56 (2003)

Hakola, T., Härmä, M.: Evaluation of a fast forward rotating shift schedule in the steel industry with a special focus on ageing and sleep. J. Hum. Ergol. 30(1–2), 35–40 (2001)

Han, W.-J.: Shift work and child behavioral outcomes. Work Employ. Soc. 22(1), 67–87 (2008)

Härmä, M., Hakola, T., Kandolin, I., Sallinen, M., Virkkala, J., Bonnefond, A., Mutanen, P.: A controlled intervention study on the effects of a very rapidly forward rotating shift system on sleep-wakefulness and well-being among young and elderly shift workers. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 59(1), 70–79 (2006)

Harrington, J.M.: Health effects of shift work and extended hours of work. Occup. Environ. Med. 58(1), 68–72 (2001)

IG Metall (German Metalworker´s Union): Manteltarifvertrag für die Beschäftigten der Volkswagen AG vom 15. Dezember 2008, gültig ab 01. Januar 2009, in der Fassung vom 15. Februar 2011. IG Metall Bezirk Niedersachsen und Sachsen-Anhalt (2008)

Jacobsen, D.I., Fjeldbraaten, E.M.: Shift work and sickness absence- the mediating roles of work-home conflict and perceived health. Hum. Resour. Manag. 57(5), 1145–1157 (2018)

Jansen, N.W.H., Kant, I., Nijhus, F.J.N., Swaen, G.M.H., Kristensen, T.S.: Impact of worktime arrangements on work-home interference among Dutch employees. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 30(2), 139–148 (2004)

Johns, G.: “How often were you absent?” A review of the use of self-reported absence data. J. Appl. Psychol. 79(4), 574–591 (1994)

Jørgensen, J.T., Karlsen, S., Stayner, L., Hansen, J., Andersen, Z.J.: Shift work and overall case-specific mortality in the Danish nurse cohort. J. Work Environ. Health 43(2), 117–126 (2017)

Kantermann, T., Juda, M., Vetter, C., Roenneberg, T.: Shift-work research: where do we stand, where should we go? Sleep Biol. Rhythms 8(2), 95–105 (2010)

Kleiven, M., Bøggild, H., Jeppesen, H.J.: Shift work and sick leave. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 24(3), 128–133 (1998)

Knutsson, A.: Health disorders of shift workers. Occup. Med. 53(2), 103–108 (2003)

Knutsson, A.: Mortality risk from shift work. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 43(2), 97–98 (2017)

Knutsson, A., Bøggild, H.: Gastrointestinal disorders among shift workers. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 36(2), 85–95 (2010)

Knutsson, A., Åkerstedt, T., Jonsson, B., Orth-Gomer, K.: Increased risk of ischemic heart disease in shift workers. Lancet 2(8498), 89–92 (1986)

Kristensen, K., Juhl, H.J., Eskildsen, J., Nielsen, J., Frederiksen, N., Bisgaard, C.: Determinants of absenteeism in a large Danish bank. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 17(9), 1645–1658 (2006)

Lazear, E.P.: Performance pay and productivity. Am. Econ. Rev. 90(5), 1346–1361 (2000)

Lesuffleur, T., Chastang, J.-F., Sadret, N., Niedhammer, I.: Psychosocial factors at work and sickness absence: results from the french national SUMER survey. Am. J. Ind. Med. 57, 695–708 (2014)

Løkke Nielsen, A.-K.: Determinants of absenteeism in public organizations: a unit-level analysis of work absence in a large danish municipality. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 19(7), 1330–1348 (2008)

López-Bueno, R., Calatayud, J., López-Sanchez, G., Smith, L., Andersen, L., Casatús, J.: Higher leisure time physical activity is associated with lower sickness absence: cross-sectional analysis using the general workforce. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 60(6), 919–925 (2020)

López-Bueno, R., Sundstrup, E., Vinstrup, J., Casatús, J., Anderson, L.: High leisure time physical activity reduces the risk of long-term sickness absence. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 30(5), 939–946 (2020)

McMenamin, T.: A time to work: recent trends in shift work and flexible schedules. Mon. Lab. Rev. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2007/12/art1full.pdf (2007). Accessed 20 Aug 2020

Meyer, M., Mpairaktari, P., Glushanok, I.: Krankheitsbedingte Fehlzeiten in der deutschen Wirtschaft im Jahr 2012. In: Badura, B., Ducki, A., Schröder, H., Klose, J., Meyer, M. (eds.) Fehlzeitenreport 2013 - Verdammt zum Erfolg - Die süchtige Arbeitsgesellschaft?, pp. 263–446. Springer, Berlin (2013)

Merkus, S.L., Van Drongelen, A., Holte, K.A., Labriola, M., Lund, T., Van Mechelen, W., Van der Beek, A.J.: The association between shift work and sick leave: a systematic review. Occup. Environ. Med. 69(10), 701–712 (2012)

Nakata, A., Haratani, T., Takahashi, M., Kawakami, N., Arito, H., Kobayashi, F., Fujioka, Y., Fukui, S., Araki, S.: Association of sickness absence with poor sleep and depressive symptoms in shift workers. Chronobiol. Int. 21(6), 899–912 (2004)

Papke, L.E., Wooldridge, J.M.: Econometric models for fractional response variables with an application to 401(k) plan participation rates. J. Appl. Econom. 11(6), 619–632 (1996)

Papke, L.E., Wooldridge, J.M.: Panel data methods for fractional response variables with an application to test pass scores. J. Econom. 145(1–2), 121–133 (2008)

Presser, H.B.: Nonstandard work schedules and marital instability. J. Marriage Fam. 62(1), 93–110 (2000)

Ropponen, A., Koskinen, A., Puttonen, S., Härmä, M.: Exposure to working-hour characteristics and short sickness absence in hospital workers: a case-crossover study using objective data. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 91, 14–21 (2019)

Sallinen, M., Kecklund, G.: Shift work, sleep, and sleepiness – differences between shift schedules and systems. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 36(2), 121–133 (2010)

Smith, L., Folkard, S., Poole, C.J.M.: Increased injuries on night shifts. Lancet 344(8930), 1137–1139 (1994)

Taylor, P.J., Pocock, S.J.: Mortality of shift and day workers 1956–68. Br. J. Ind. Med. 29, 201–207 (1972)

Tüchsen, F., Christensen, K.B., Nabe-Nielsen, K.: Does evening work predict sickness absence among female carers of the elderly? Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 34(6), 483–486 (2008)

Van Amelsvoort, L., Jansen, N., Swaen, G., Van den Brandt, P., Kant, I.: Direction of shift rotation among three-shift workers in relation to psychological health and work-family conflict. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 30(2), 149–156 (2004)

Vetter, C., Devore, E., Wegrzyn, L., Massa, J., Speizer, F., Kawachi, I., Rosner, B., Stampfer, M., Schernhammer, E.: Association between rotating night shift work and risk of coronary heart disease among women. JAMA Netw. 315(16), 1726–1734 (2016)

Vidacek, S., Kaliterna, L., Radosevic-Vidacek, B., Folkard, S.: Productivity on a weekly rotating shift system: circadian adjustment and sleep deprivation effects? Ergonomics 29(12), 1583–1590 (1986)

Wang, X.-S., Armstrong, M.E.G., Cairns, B.J., Key, T.J., Travis, R.C.: Shift work and chronic disease: the epidemiological evidence. Occup. Med. 61(2), 78–89 (2011)

Funding

The project received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frick, B., Simmons, R. & Stein, F. Timing matters: worker absenteeism in a weekly backward rotating shift model. Eur J Health Econ 21, 1399–1410 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01232-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01232-6