Abstract

France has first experimented, in 2009, and then generalized a practice level add-on payment to promote Multi-Professional Primary Care Groups (MPCGs). Team-based practices are intended to improve both the efficiency of outpatient care supply and the attractiveness of medically underserved areas for healthcare professionals. To evaluate its financial attractiveness and thus the sustainability of MPCGs, we analyzed the evolution of incomes (self-employed income and wages) of General Practitioners (GPs) enrolled in a MPCG, compared with other GPs. We also studied the impacts of working in a MPCG on GPs’ activity through both the quantity of medical services provided and the number of patients encountered. Our analyses were based on a quasi-experimental design, with a panel dataset over the period 2008–2014. We accounted for the selection into MPCG by using together coarsened exact matching and difference-in-differences (DID) design with panel-data regression models to account for unobserved heterogeneity. We show that GPs enrolled in MPCGs during the period exhibited an increase in income 2.5% higher than that of other GPs; there was a greater increase in the number of patients seen by the GPs’ (88 more) without involving a greater increase in the quantity of medical services provided. A complementary cross-sectional analysis for 2014 showed that these changes were not detrimental to quality in terms of bonuses related to the French pay-for-performance program for the year 2014. Hence, our results suggest that labor and income concerns should not be a barrier to the development of MPCGs, and that MPCGs may improve patient access to primary care services.

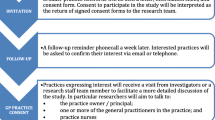

Source: Appariement Cnam-DGFiP Drees

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This study is part of a broader evaluation project that aims to address several aspects of MPCGs using a mixed methods approach.

GPs who have fulfilled certain conditions can enter into a contract authorizing them to charge extra fees, which derogates from the standard fee schedule. They account for 10% of the self-employed GPs and will not be discussed further as they will be excluded from our study sample.

25% of GPs had additional salaried activities in 2014, and the associated income represented on average 20% of their total income.

The decrees of 23 February 2015 and 24 July 2017 endorsed a continuation of the scheme and presented the eligibility frameworks for voluntary structures (Accord Conventionel Interprofessionnel pour les Structures de Santé Pluriprofessionnelles de Proximité).

Technical procedures, such as stitches or imaging, for example, involve specific fees that are added to the regulated fees for the consultation.

Matching with different criteria including pre-treatment outcomes has also been performed to check the robustness of our results. It involved the use of propensity score matching to better deals with the several continuous matching criteria (see Sect. 5.3 for more details).

This assumption was, furthermore, supported by robustness analysis that parametrically tested the existence of differences in trends before 2008 (see Table 4 in Appendix).

More precisely, we used the felm function from the R package lfe with dummy variable for treatment and time (which amount to use xtreg, fe function in stata). We opted for introducing a time dummy over using the two-way fixed-effect estimator (which is equivalent in our setting), in order to acknowledge the trend of the control group.

The pooled DID model, (1), that we estimate by OSL was: \(Y_{it} = \alpha + \alpha_{g} {\text{MPCG}}_{i} + \lambda d14_{t} + \delta MPCG_{i} *d14_{t} + \beta_{1} Z_{i} + \beta_{2} X_{it} + u_{it}\), where \(\alpha_{g}\) captures the permanent difference between the group of treated and control GPS in the spirit of classic DID setting and \(Z_{i}\) is a vector of constant covariates over time. The pooled DID model does not fully exploit our individual panel dataset and, in principle, is less accurate for our purposes. However, it can be used as a benchmark and allows to estimate the interesting effects of time-invariant characteristics such as gender or living areas effects.

Those descriptive analyses have been further confirmed by replications of our parametric analyses to test dynamics differential in terms of the share of patients with chronic diseases, share of patients over 65 years old or under 15 years old and the share of patients with free complementary health insurance (CMU-C) (available upon request).

References

Ono, T., Schoenstein, M., Buchan, J.: Geographic imbalances in doctor supply and policy responses (2014). https://doi.org/10.1787/5jz5sq5ls1wl-en

Frélaut, M.: Les déserts médicaux. Regards 53, 105–116 (2018)

Vergier, N., Chaput, H.: Déserts médicaux : comment les définir ? Comment les mesurer ? Les dossiers de la Drees n°17. Mai (2017)

Groenewegen, P., Heinemann, S., Greß, S., Schäfer, W.: Primary care practice composition in 34 countries. Health Policy 119, 1576–1583 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.08.005

Mousquès, J.: Le regroupement des professionnels de santé de premiers recours : quelles perspectives économiques en termes de performance ? Revue francaise des affaires sociales. pp. 253–275 (2011)

Newhouse, J.P.: The economics of group practice. J. Hum. Resour. 8, 37–56 (1973). https://doi.org/10.2307/144634

Propper, C., Nicholson, A.: The organizational form of firms: why do physicians form groups? In Handbook in Health Economics. pp. 911–916 (2012)

Jesmin, S., Thind, A., Sarma, S.: Does team-based primary health care improve patients’ perception of outcomes? Evidence from the 2007–08 Canadian Survey of Experiences with Primary Health. Health Policy 105, 71–83 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.01.008

Mickan, S.M.: Evaluating the effectiveness of health care teams. Aust. Health Rev. 29, 211–217 (2005)

Strumpf, E., Ammi, M., Diop, M., Fiset-Laniel, J., Tousignant, P.: The impact of team-based primary care on health care services utilization and costs: Quebec’s family medicine groups. J. Health Econ. 55, 76–94 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.06.009

Chevillard, G., Mousquès, J., Lucas-Gabrielli, V., Rican, S.: Has the diffusion of primary care teams in France improved attraction and retention of general practitioners in rural areas? Health Policy. 123, 508–515 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.03.002

Holte, J.H., Kjaer, T., Abelsen, B., Olsen, J.A.: The impact of pecuniary and non-pecuniary incentives for attracting young doctors to rural general practice. Soc. Sci. Med. 128, 1–9 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.022

Ammi, M., Diop, M., Strumpf, E.: Explaining primary care physicians’ decision to quit patient-centered medical homes: evidence from Quebec, Canada. Health Serv. Res. 54, 367–378 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13120

Heam, J.C., Mikou, M., Ferreti, C., et al.: Les dépenses de santé en 2018 : Résultats des comptes de la santé. Edition 2018. Panoramas de la DREES (2019)

Dumontet, M., Buchmueller, T., Dourgnon, P., Jusot, F., Wittwer, J.: Gatekeeping and the utilization of physician services in France: evidence on the Médecin traitant reform. Health Policy 121, 675–682 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.04.006

Mousquès, J., Cartier, T., Chevillard, G., Couralet, P.-E., Daniel, F., Lucas-Gabrielli, V., Bourgueil, Y., Affrite, A.: L’évaluation de la performance des maisons, pôles et centres de santé dans le cadre des Expérimentations des nouveaux modes de rémunération (ENMR) sur la période 2009-2012. Rapport Irdes. (2014)

Bourgeois, I., Fournier, C.: Contractualiser avec l’Assurance maladie : un chantier parmi d’autres pour les équipes des maisons de santé pluriprofessionnelles. Rev. Fr. Aff. Soc. 1, 167–193 (2020)

Bont, A., Exel, J., Coretti, S., Ökem, Z., Janssen, M., Hope, K.L., Ludwicki, T., Zander-Jentsch, B., Zvonickova, M., Bond, C., Wallenburg, I.: Reconfiguring health workforce: a case-based comparative study explaining the increasingly diverse professional roles in Europe. BMC Health Serv. Res. 16, 637 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1898-0

Grumbach, K., Bodenheimer, T.: Can health care teams improve primary care practice? JAMA 291, 1246–1251 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.10.1246

Schuetz, B., Mann, E., Everett, W.: Educating health professionals collaboratively for team-based primary care. Health Aff. 29, 1476–1480 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0052

Defelice, L.C., Bradford, W.D.: Relative inefficiencies in production between solo and group practice physicians. Health Econ. 6, 455–465 (1997)

Kimbell, L.J., Lorant, J.H.: Physician productivity and returns to scale. Health Serv. Res. 12, 367–379 (1977)

Reinhardt, U.: A production function for physician services. Rev. Econ. Stat. 54, 55–66 (1972). https://doi.org/10.2307/1927495

Rosenman, R., Friesner, D.: Scope and scale inefficiencies in physician practices. Health Econ. 13, 1091–1116 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.882

Milliken, O., Devlin, R.A., Barham, V., Hogg, W., Dahrouge, S., Russell, G.: Comparative efficiency assessment of primary care service delivery models using data envelopment analysis. Can. Public Policy 37, 85–109 (2011)

Sarma, S., Devlin, R.A., Hogg, W.: Physician’s production of primary care in Ontario, Canada. Health Econ. 19, 14–30 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1447

Adorian, D., Silverberg, D.S., Tomer, D., Wamosher, Z.: Group discussions with the health care team–a method of improving care of hypertension in general practice. J. Hum. Hypertens. 4, 265–268 (1990)

Bodenheimer, T., Wagner, E.H., Grumbach, K.: Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA 288, 1775–1779 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.14.1775

Callahan, C.M., Boustani, M.A., Unverzagt, F.W., Austrom, M.G., Damush, T.M., Perkins, A.J., Fultz, B.A., Hui, S.L., Counsell, S.R., Hendrie, H.C.: Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 295, 2148–2157 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.18.2148

Renders, C., Valk, G., Griffin, S., Wagner, E., van Eijk, J., Assendelft, W.: Interventions to improve the management of diabetes in primary care, outpatient, and community settings: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 24, 1821–1833 (2001). https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.24.10.1821

Rosenthal, M.B., Sinaiko, A.D., Eastman, D., Chapman, B., Partridge, G.: Impact of the Rochester Medical Home Initiative on primary care practices, quality, utilization, and costs. Med. Care 53, 967–973 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000424

Rebitzer, J.B., Votruba, M.E.: Organizational economics and physician practices. In: Culyer, A.J. (ed.) Encyclopedia of health economics, pp. 414–424. Elsevier, San Diego (2014)

Encinosa, W.E., Gaynor, M., Rebitzer, J.B.: The sociology of groups and the economics of incentives: Theory and evidence on compensation systems. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 62, 187–214 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2006.01.001

Gaynor, M., Gertler, P.: Moral hazard and risk spreading in partnerships. RAND J. Econ. 26, 591–613 (1995). https://doi.org/10.2307/2556008

Fournier, C.: Travailler en équipe en s’ajustant aux politiques : un double défi dans la durée pour les professionnels des maisons de santé pluriprofessionnelles. Journal de gestion et d’economie de la sante. 37(1), 72–91 (2019)

Harris, M.F., Advocat, J., Crabtree, B.F., Levesque, J.-F., Miller, W.L., Gunn, J.M., Hogg, W., Scott, C.M., Chase, S.M., Halma, L., Russell, G.M.: Interprofessional teamwork innovations for primary health care practices and practitioners: evidence from a comparison of reform in three countries. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 9, 35–46 (2016). https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S97371

Schadewaldt, V., McInnes, E., Hiller, J.E., Gardner, A.: Views and experiences of nurse practitioners and medical practitioners with collaborative practice in primary health care—an integrative review. BMC Fam. Pract. 14, 132 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-132

Gaynor, M., Pauly, M.V.: Compensation and productive efficiency in partnerships: evidence from medical groups practice. J. Political Econ. 98, 544–573 (1990)

Kantarevic, J., Kralj, B., Weinkauf, D.: Enhanced fee-for-service model and physician productivity: evidence from Family Health Groups in Ontario. J. Health Econ. 30, 99–111 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.10.005

McGuire, T.G.: Physician agency and payment for primary medical care. In: The Oxford Handbook of Health Economics (2011). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199238828.013.002

Bolduc, D., Fortin, B., Fournier, M.-A.: The effect of incentive policies on the practice location of doctors: a multinomial probit analysis. J. Labor Econ. 14, 703–732 (1996)

Delattre, E., Samson, A.L.: Stratégies de localisation des médecins généralistes français: mécanismes économiques ou hédonistes ? Econ. Stat. 455, 115–142 (2012). https://doi.org/10.3406/estat.2012.10020

Hurley, J.: Physicians’ choices of specialty, location, and mode: a reexamination within an interdependent decision framework. J. Hum. Resour. 26, 47–71 (1991)

Becker, G.S., Murphy, K.M.: The division of labor, coordination costs, and knowledge. Q. J. Econ. 107, 1137–1160 (1992). https://doi.org/10.2307/2118383

Meltzer, D.O., Chung, J.W.: Coordination, Switching Costs and the Division of Labor in General Medicine: An Economic Explanation for the Emergence of Hospitalists in the United States. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge (2010)

Gaynor, M.: Competition within the firm: theory plus some evidence from medical group practice. RAND J. Econ. 20, 59–76 (1989). https://doi.org/10.2307/2555651

Grumbach, K., Coffman, J.: Physicians and nonphysician clinicians: complements or competitors? JAMA 280, 825–826 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.9.825

Chevillard, G., Mousquès, J.: Accessibilité aux soins et attractivité territoriale : proposition d’une typologie des territoires de vie français. Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography. (2018). https://doi.org/10.4000/cybergeo.29737

Mikol, F., Franc, C.: Gender differences in the incomes of self-employed french physicians: the role of family structure. Health Policy. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.05.002

Iacus, S.M., King, G., Porro, G.: Multivariate matching methods that are monotonic imbalance bounding. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 106, 345–361 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2011.tm09599

Ho, D.E., Imai, K., King, G., Stuart, E.A.: Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Anal. 15, 199–236 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpl013

Chabé-Ferret, S.: Should we combine difference in differences with conditioning on pre-treatment outcomes? Toulouse school of economics (TSE) (2017)

Lindner, S., McConnell, K.J.: Difference-in-differences and matching on outcomes: a tale of two unobservables. Health Serv. Outcomes Res. Method. 19, 127–144 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-018-0189-0

King, G., Nielsen, R.: Why propensity scores should not be used for matching. Political Anal. 27, 435–454 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2019.11

Iacus, S.M., King, G., Porro, G.: A theory of statistical inference for matching methods in causal research. Political Anal. 27, 46–68 (2019)

Acknowledgements

We thank the Drees (Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques) for letting us access to their facilities and to the CNAMTS-DGFiP database.

Funding

Funding for the French survey. Research grant from NHI for the evaluation program pilot by IRDES and CESP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Details of CEM criteria

CEM allows us to control imbalances bound between the treated and control groups, while the large size of the non-MGP sample allows us to use exact matching without discarding too many treated GPs. The continuous variable age was broken down into nine categories from 27 to 30-year-old GPs and then by 5-year increments from 30 to 60-year-old GPs (the oldest GP in the study sample was 59). Furthermore, to better control for GPs’ career profiles we also matched on whether GPs had practiced in private practice for more or less than 5 years. Indeed, depending on the year in which they set up in private practice (e.g., after practicing in a hospital), GPs could be exposed to early carrier ramp-up at different ages. With regard to the number of children, we included the GPs with strictly more than 3 in the same category. Finally, we defined a regular additional salaried activity as one that generated more than €4000 per year, which amounted to 5% of the average total income in 2008.

To achieve a balanced sample, we opted for weighting the standard GPs in each subclass, so that their distribution over the subclass corresponded to that of the GPs in MPCGs: all of whom had a weight equal to 1, while the weights of control GPs were normalized to sum up their actual number. More precisely, the CEM and consecutive weighting were computed with the MatchIt package in R, so that the control GPs’ weights within each exact matching’s subclass is (the number of treated within the subclass/the number of controls within the subclass) * (Overall number of control/Overall number of treated). In contrast to selecting a given ratio of control GPs within each subclass, as in m-to-1 matching approach, it enabled us to keep as much information as possible on the control group and to estimate the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT), provided that the same weights were used in the regression analysis.

Robustness analyses

The remainder of the “Appendix” presents selected tables from our robustness analysis (further results from robustness checks are available upon request).

The last two tables (Tables 6 and 7) present the replication of our parametric analysis when the control group was identified through PSM, and additional matching criteria were introduced. The following details more precisely the procedure which we used. The propensity score was estimated in 2008 (pre-reform period) using a logistic model that predicted the likelihood of joining an accredited MPCGs in function of: the socio-demographic and territorial covariates used in our original CEM, case mix details (share of patients according to their age, patients with free complementary health insurance, and patients with a chronic disease), as well as the number of patients seen, the number of medical services, the GP’s gross revenues, self-employed and salaried income, and the share of home visits and procedures in GPs’ gross revenues. The matching uses nearest-neighbor’s criterion to select 3 control GPs for each GP in a MPCG, and balances territorial socio-demographic characteristics, activity (visits and patients), and incomes. After the PSM, there were no significative differences in the pre-reform period in 2008 with regard to all the criteria included in the logistic model (descriptive statistics of the balanced sample are available on request).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cassou, M., Mousquès, J. & Franc, C. General practitioners’ income and activity: the impact of multi-professional group practice in France. Eur J Health Econ 21, 1295–1315 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01226-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01226-4