Abstract

The endoscopic endonasal approach is more disruptive to normal anatomy (particularly nasal mucosa) than the transseptal submucosal microscopic approach. This may result in greater postoperative nasal morbidity, in turn reducing quality of life. We aimed to assess the severity and time course of nasal morbidity, and its impact on quality of life, following endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery in this retrospective cohort study. We identified 95 patients who underwent endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery for anterior skull base pathologies. Nasal-specific questions from the Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22 (SNOT-22) and the Anterior Skull Base inventory (ASB-12) were combined with quality-of-life questions. Patient demographics, diagnosis, and operative data were collected from electronic records. Age of the cohort ranged from 14–83 years. Time elapsed since surgery ranged from 3–85 months. 85/95 (89%) felt that nasal morbidity associated with surgery was acceptable, given the underlying reason for, and outcome of surgery; 10/95 (11%) did not. 71/95 (75%) reported no change or improvement in olfaction 3-months following surgery. 24/95 (25%) reported a deterioration in olfaction which was mild in 7%, moderate in 7%, and severe in 11%. Nasal crusting, nasal obstruction, and headache were moderately problematic symptoms but improved significantly by 3-month follow-up. Nasal discharge, nasal pain, and nasal whistling were mildly problematic and improved significantly by 3-months. 62/95 (65%) patients reported ‘no change’ in day-to-day activities due to the effects on their nose after surgery. 19/95 (20%) had ‘mild inconvenience’, 8/95 (8%) ‘moderate inconvenience’ and 6/95 (6%) ‘severe inconvenience’. Endoscopic anterior skull base surgery is associated with nasal morbidity. Whilst 35% of patients appreciate a consequent negative impact on day-to-day life, the overwhelming majority feel that nasal morbidity is acceptable, given the wider surgical goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Endoscopic or endoscope-assisted approaches to the skull base are proliferating. Endoscopic approaches to the anterior skull base occur predominantly via the nasal corridor and paranasal sinuses [19]. In many settings, the endoscope has replaced the previously used microscopic transseptal submucosal approach [7]. There is consensus that the endoscope provides better visualisation [13] and some data suggests shorter hospital stays [10] and improved extent of tumour resection [1, 13]. However, compared with the submuco-perichondrial corridor used in microscopic surgery, the endoscopic approach is more disruptive to normal anatomy (particularly nasal mucosa) [4]. This may result in higher levels of postoperative nasal morbidity which may in turn reduce quality of life.

Multiple tools and scoring systems have been used to assess nasal morbidity after endoscopic endonasal surgery. The most common is the Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22 (SNOT-22), a symptom-based patient-reported questionnaire consisting of 22 items reported across 5 domains (rhinologic, extra-nasal rhinologic, ear/facial, psychological/sleep). Each question is scored on a Likert scale with higher scores indicating higher levels of patient-reported nasal morbidity [6]. Importantly, the SNOT-22 questionnaire was originally developed for use in chronic rhinosinusitis and not in the context of endonasal endoscopic skull base surgery [2, 11]. By contrast, the Anterior Skull Base Nasal inventory-12 (ASK-12) was developed and validated specifically for endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery [12]. However, both tools are symptom-specific and do not capture the wider impact that nasal morbidity may have upon overall quality of life. As a result, other validated quality of life assessment tools (not specific to nasal morbidity) have sometimes been used separately or in parallel. For example, the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36).

Appreciating the relative contribution of postoperative nasal morbidity to overall quality of life demands nuanced patient-reported outcome measures. To explore this further, we developed a hybrid patient-reported assessment tool encapsulating relevant nasal symptoms and broader impacts on quality of life. We deployed this assessment retrospectively to assess 95 patients who underwent endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery during the period in which our unit transitioned from microscopic to endoscopic approaches (2014 to 2021).

Materials and methods

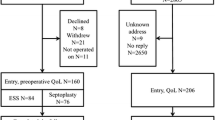

All patients who underwent endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery in Edinburgh between October 2014 and November 2021 were identified from a prospectively maintained, Caldicott-approved database. During this transition period, from a microscopic to predominantly endoscopic endonasal approach, 146 patients underwent endoscopic anterior skull base surgery. Of these, 12 patients were deceased by the time of the study, 28 could not be contacted, and 11 patients declined to participate. 95 patients (52 female and 43 male, range of time since operation 3 to 85 months) were contacted and completed a telephone questionnaire.

Patient demographic data, underlying diagnosis, and surgical operative data were collected from our electronic patient management system. Pre-operative data included patient age at the time of operation, sex, pathology, previous transsphenoidal surgery (number of previous surgeries and whether endoscopic or microscopic approach), and any pertinent past medical history.

Patients completed the questionnaire (detailed below) retrospectively and by telephone. For patients who underwent more than one transsphenoidal surgery during the study time window, the questionnaire was performed only once and in relation to their most recent surgery. Data was consolidated in Excel (Microsoft, USA) and statistical analysis (t-test) was performed using GraphPad Prism (Dotmatics, USA). Since the pathology being targeted by surgery may itself impact nasal morbidity and determines specific aspects of the surgical approach which variably impact nasal morbidity, we analysed separate subgroups: (1) non-expanded endoscopic transsphenoidal approaches to the sella, (2) expanded transsphenoidal approaches to the sella, (3) approaches to nasal sinus-centred pathology, and (4) operations for olfactory neuroblastoma (Table 1).

Results

The age of the cohort ranged from 14 to 83 years (mean 51). Time elapsed since surgery ranged from 3 to 85 months (mean 34 months). 48 patients underwent surgery for non-functional pituitary macroadenoma and 13 for functional adenomas (8 for acromegaly, 4 for Cushing’s disease, and 1 prolactinoma). 9 patients underwent surgery for craniopharyngioma, 6 for Rathke’s cleft cyst, 6 for CSF leak (due to encephalocoele or trauma), 3 for olfactory neuroblastoma (all of whom underwent a concurrent transcranial subfrontal approach), 2 for clival chordoma, 2 for chondrosarcoma. There was one instance of surgery for each of meningioma, trigeminal schwannoma, sinonasal sarcoma, juvenile nasal angiofibroma, osteoma, and sellar arachnoid cyst.

Considering the cohort together, 85/95 (89%) felt that the nasal morbidity associated with surgery was acceptable to them, given the underlying reason and outcome of surgery; 10/95 (11%) did not. 62/95 (65%) patients reported ‘no change’ to day-to-day activities due to effects on their nose after surgery. 19/95 (20%) had ‘mild inconvenience’, 8/95 (8%) ‘moderate inconvenience’ and 6/95 (6%) reported ‘severe inconvenience’.

71/95 (75%) reported no change or improvement in olfaction following surgery. 24/95 (25%) reported a deterioration in olfaction at the time of questioning: mild in 7%, moderate in 7%, and severe in 11%. Nasal crusting, nasal obstruction, and headache were moderately problematic symptoms initially, but all improved significantly by 3-month follow-up. Nasal discharge, nasal pain, and nasal whistling were mildly problematic issues which also improved significantly by 3-month follow up. See Fig. 1.

Non-expanded endoscopic transsphenoidal approaches to the sella (n = 68, including pituitary adenoma, Rathke cleft cyst)

59/68 (87%) felt that the after-effects of surgery were acceptable, given the underlying reason and outcome of surgery. One patient was not sure and 8/69 (12%) did not feel that the nasal morbidity associated with surgery was acceptable. Free text responses included: nasal symptoms were “initially very bad but improved”, nasal symptoms “most definitely” acceptable, “absolutely” acceptable, ‘no problems after surgery”, “slight inconvenience”, “tumour was removed, so it’s all good”, surgery “was essential as tumour was affecting my eyesight”, surgery was “definitely worth it because I would have lost my eyesight”, “it was horrendous initially but it did get better”, “it was the right thing to do, I was aware of possible symptoms”, “everyone was great but idk (sic) if it was worth it. I don’t feel great, very tired now”.

For 25/68 patients (37%), the impact of surgery on their nose continues to cause some degree of inconvenience. For 13/68 (19%) this is mild, for 8/68 (12%) this is moderate, and for 4/68 (6%) patients, the inconvenience is severe. 50/68 (74%) reported no change or improvement in olfaction following surgery. 18/68 patients (26%) reported a deterioration in olfaction: mild in 9%, moderate in 10%, and severe in 7%. Figure 2 shows the impact of surgery on nasal symptoms of crusting, discharge, pain, obstruction, headache, whistling, and capacity to achieve rest. Headache and nasal crusting were the most problematic of these symptoms (of mild/moderate severity). The severity of all nasal symptoms reduced significantly by 3-month follow-up.

Expanded transsphenoidal approaches to the sella (n = 15, as was indicated for surgery for chordoma, craniopharyngioma, meningioma)

14/15 (93%) felt that the after-effects of surgery were acceptable, given the underlying reason and outcome of surgery. 1/15 (7%) did not feel that nasal morbidity associated with surgery was acceptable. Free text responses included: nasal side effects were “absolutely acceptable”, and they are “acceptable if able to remove the tumour”. 12/15 (80%) reported no change or improvement in olfaction following surgery. 3/15 patients (20%) reported a deterioration in olfaction: mild in 7% and severe in 13%. Figure 3 shows the impact of surgery on the nasal symptoms of crusting, discharge, pain, obstruction, headache, whistling, and capacity to achieve rest. Nasal obstruction and headache were mildly problematic in the early post-operative period but improved by 3-months. For 4/15 patients (27%), nasal side effects continue to cause some degree of inconvenience. For 3/15 this is mild and for 1/15 patients this is severe inconvenience.

Considering those patients who underwent revision transsphenoidal surgery, there was a similar impact on olfaction when compared with those undergoing index procedures. 13 patients underwent revision operations. 11/13 (85%) reporting stable or improved olfaction post-surgery and 2/13 reporting deterioration (one mild, one severe).

Endoscopic approaches to nasal sinus-centred pathology and the paramedian floor of the anterior fossa (n = 9, including anterior fossa encephalocele and sinonasal tumours)

9/9 (100%) felt that the after-effects of surgery were acceptable, given the underlying reason and outcome of surgery. Free text responses included: “nose symptoms now are not as bad as before”. 9/9 (100%) reported no change or improvement in olfaction following surgery. Figure 4 shows the impact of surgery on nasal symptoms of crusting, discharge, pain, obstruction, headache, whistling, and capacity to achieve rest. In this cohort, these symptoms were mild at worst and often absent. For 3/9 patients (33%), the impact on their nose caused a mild degree of inconvenience.

Surgery for olfactory neuroblastoma (n = 3) – all underwent combined endonasal and transcranial subfrontal approach

3/3 (100%) felt that the after-effects of surgery were acceptable, given the underlying reason and outcome of surgery. Free text responses included: nasal side effects were a “small price to pay” and nasal side effects were “absolutely acceptable”. This pathology directly threatens olfaction, and all three cases were treated by combined endonasal and transcranial sub-frontal approaches. All three patients had subjectively severely worse olfaction following treatment. Figure 5 shows the impact of surgery on nasal symptoms of crusting, discharge, pain, obstruction, headache, whistling, and capacity to achieve rest. Nasal obstruction was a severe problem whilst nasal crusting and nasal discharge were moderately severe. One patient reports severe inconvenience because of nasal morbidity.

Discussion

A meta-analysis in 2019 by Bhenswala et al. assessed sino-nasal morbidity after endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery [2]. 19 studies were analysed, combining 27 datasets into a population of 1025 patients and reporting pre-operative and follow-up SNOT-22 data at < 4 weeks, 12-weeks, 26-weeks, 52-weeks, and > 96-weeks follow-up. Overall, SNOT-22 scores were significantly worse at the < 4-week follow-up, but significantly improved at all subsequent follow-up times. Whilst this work illustrates that this scoring system captures important symptomatic changes, it does not correlate these changes with the overall impact on patient-reported quality of life, nor relate the impact to the underlying disease process being targeted by the operation. We qualitatively assessed relevant studies published since Bhenswala’s meta-analysis of 2019, reviewing the Sino-Nasal Outcomes Test-22 (SNOT-22) and Anterior Skull Base Inventory-12 (ASB-12) and comparing – when possible – with quality-of-life assessment tools (SF-36, ASBS-Q, and the EQ-5D). Embase and MEDLINE databases were interrogated with the search phrase [(“endoscopic endonasal” OR “endoscopic transsphenoidal”) AND (“nasal morbidity” OR “sino-nasal outcome” OR “sino-nasal outcome test 22”)]. 12 contemporary papers were identified [3, 5, 8, 9, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Scagnelli et al. demonstrated that overall SNOT-22 scores followed the expected rise and fall pattern after endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery. However, when looking at subdomains, only the rhinologic and sleep domains were found to be significantly different [18]. Hallén et al. found similar results with only rhinological domains (taste and smell; postnasal discharge; thick nasal discharge; and need to blow nose scores) significantly worsening [8]. Novák et al. found a similar pattern. The need to blow the nose, nasal discharge, thick discharge, and loss of smell and taste were all significantly worse, despite no significant difference in the overall score being noted [14]. Hannan et al. found that the nasal domains and olfactory score were significantly worse but found no significant change in the overall score [9]. This shows again that the SNOT-22 is a valid method of detecting sinonasal symptom change after endonasal skull base surgery but reiterates that it lacks specificity, due to several unnecessary and non-relevant components (e.g., assessing ear fullness, ear pain, and dizziness).

Regarding quality of life, Schreiber et al. found that while there was no significant difference between preoperative and 6-month follow-up in either the SNOT-22 or ASK-12 scores, there was a significant improvement in the SF-36 quality of life score [19]. Dolci et al. also found no significant difference in SNOT-22 scores at 3- and 6-months follow-up but did find a significant improvement in SF-36 at both time points [5]. Neiderman et al. found an improvement on the ASBS-Q at 4 to 6 months in the “pain-related” and “vitality-related” domains in the absence of a significant difference in SNOT-22 [3]. Hallén et al. noted a significant worsening of the rhinologic component of the SNOT-22 at 6-months compared with baseline, yet a significant increase on the EQ-5D [8]. These changes are therefore likely to reflect other aspects of the patient journey. For example, improvement in vision after decompressing the optic apparatus might well outweigh, in the patient’s opinion, mildly inconvenient post-operative sinonasal symptoms.

We found that whilst 85/95 (89%) felt that the nasal morbidity associated with surgery was acceptable, given the underlying reason and outcome of surgery, 10/95 (11%) did not. It is important to consider this minority in more detail. Some specific cases are considered below:

-

(i)

A 57-year-old chef, with no significant past medical history, had a non-secretory pituitary macro-adenoma causing optic apparatus compression. Post-operatively, he reported moderate nasal crusting, mild nasal discharge, no nasal pain, mild ongoing nasal obstruction, no headache, ongoing nasal whistling, pre-existing, and ongoing issues with sleep, and reported that his smell was significantly worse. His vision recovered well. He feels ‘constantly tired’ after surgery, though he has normal postoperative pituitary function. He disengaged from follow-up from the outset, with numerous failures to attend for follow-up imaging, nursing, endocrine, and neurosurgical assessments. As a chef, the impact of impaired olfaction will be particularly pertinent.

-

(ii)

A 40-year-old woman had a diagnosis of acromegaly. Her past medical history was significant for ongoing opiate addiction, anxiety and depression, and prior surgery for cauda equina syndrome. Post-operatively, she reported severe nasal crusting, discharge, and mild obstruction (all of which resolved within a month). She has ongoing headaches, severe problems with sleep, and reports that her sense of smell is mildly worse. Whilst her growth hormone excess was significantly improved by surgery, she did quite meet criteria for remission. She is currently on medical therapy (a somatostatin analogue) and there is no surgically accessible residual adenoma on post-operative MRI. Whilst the nasal symptoms clearly contribute to her dissatisfaction, her overall quality of life is impacted by other factors. These include those related to the underlying diagnosis of acromegaly and are probably compounded by her comorbidities.

-

(iii)

A 59-year-old woman underwent a 5th operation for a recurrent Rathke’s cleft cyst causing compressive optic neuropathy and visual loss. Her four prior operations were microscopic. She has a past medical history of obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, anxiety, delusional disorder, obesity, and panhypopituitarism. Post-operatively, she appreciated an immediate improvement in vision, no change to smell, and only transient moderate nasal obstruction. The most recent operation involved minimal re-opening of an existing sphenoidotomy and no disturbance of the turbinates. Despite improvement in her vision, and only very subtle surgery in the nose, she did not feel nasal morbidity was acceptable. It is likely that her extensive psychiatric comorbidities inform her own overall assessment.

-

(iv)

A 69-year-old woman underwent revision surgery for a recurrent non-secretory pituitary macroadenoma causing compressive optic neuropathy. Her past medical history included osteopenia, vertebral insufficiency fractures, and hypopituitarism (following prior transsphenoidal operations). Post-operatively, her vision was well-preserved. She reported no nasal side-effects other than mildly reduced sense of smell. She has since gone on to have postoperative radiotherapy with significant ongoing fatigue. The fatigue seems to be clouding her overall quality of life assessment, leading to global dissatisfaction.

These cases highlight the difficulty in trying to define and quantify the relative contribution of postoperative nasal symptoms to overall quality life. Some patients did not feel surgery was worthwhile despite minimal nasal side-effects and clear success in achieving the primary surgical goal (e.g., preservation of vision). Some reported significant nasal symptoms but found this entirely acceptable, given other outcomes from surgery. Some patients have separate health or social issues which dominate or cloud their own assessment of the success – or otherwise – of their endoscopic skull base surgery. As such, it may be impossible to alter or improve some of the issues at play.

These findings echo those of some prior studies, where quality of life changes were not congruous with sinonasal symptom burden [5, 19]. Interestingly, patients undergoing some of the most expanded (and therefore most morbid) surgical approaches (e.g., for olfactory neuroblastoma or chordoma) had relatively high levels of satisfaction. These tumours are not benign (compared with pituitary adenoma or Rathke cleft cyst) and the way we counsel patients and articulate surgical goals in these contexts is consequently very different. This will colour how patients consider post-operative morbidity and may explain the relative tolerance of nasal morbidity.

We now provide more granular detail during consent regarding potential nasal morbidity from anterior endoscopic skull base surgery, informed by data from this study. From a technical perspective, we try to avoid resection of nasal turbinates unless necessary for access. We underline the utility of and strongly encourage post-operative nasal douching (from 48 h). We also review patients earlier in the ENT clinic for nasoendoscopy and, when needed, decrusting.

This study has limitations, notably its retrospective nature. The variability in time of follow up is suboptimal, ranging from 3 to 85 months. Patients that were followed up very recently after surgery may still be in the recovery period and report symptoms which may yet resolve. Conversely, patients that were followed up several years after surgery may have difficulty in accurately remembering symptoms and their duration leading to recall bias. Future studies would be improved by conducting the questionnaire at set postoperative time points, including assessment of pre-operative sinonasal symptoms.

Conclusions

Endoscopic anterior skull base surgery is associated with nasal morbidity. For the overwhelming majority of patients, nasal morbidity is acceptable given the underlying context and outcome of surgery. Nasal crusting, nasal obstruction, and headache are moderately problematic symptoms initially but improve significantly by 3-month follow-up. Nasal discharge, nasal pain, and nasal whistling are mildly problematic issues and improve significantly by 3-month follow-up. A small minority of patients appreciate a significant deterioration in quality of life which they attribute to postoperative nasal morbidity. Optimisation of consent, surgical technique, and follow-up are all important in minimising morbidity and managing expectations.

Data availability

All data that was used in the study to derive our findings is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Almutairi RD, Muskens IS, Cote DJ et al (2018) Gross total resection of pituitary adenomas after endoscopic vs. microscopic transsphenoidal surgery: a meta-analysis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 160(5):1005–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-017-3438-z

Bhenswala PN, Schlosser RJ, Nguyen SA, Munawar S, Rowan NR (2019) Sinonasal quality-of-life outcomes after endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 9(10):1105–1118. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22398

Carmel Neiderman NN, Wengier A, Dominsky O et al (2021) A Prospective Evaluation of Quality of Life in Patients Undergoing Extended Endoscopic Endonasal Surgery for Benign Pituitary Gland Lesion. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 83(Suppl2):e386–e394. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1730322

Casler JD, Doolittle AM, Mair EA (2005) Endoscopic surgery of the anterior skull base. Laryngoscope 115(1):16–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000150681.68355.85

Dolci RLL, de Moraes LT, de Carvalho ACM et al (2021) Quality-of-life evaluation for patients submitted to nasal endoscopic surgery for resection of pituitary tumours. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 278(5):1411–1418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06381-1

Erskine SE, Hopkins C, Clark A et al (2017) SNOT-22 in a control population. Clin Otolaryngol 42(1):81–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.12667

Goudakos JK, Markou KD, Georgalas C (2011) Endoscopic versus microscopic trans-sphenoidal pituitary surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol 36(3):212–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-4486.2011.02331.x

Hallén T, Olsson DS, Farahmand D et al (2021) Sinonasal Symptoms and Self-Reported Health before and after Endoscopic Pituitary Surgery-A Prospective Study. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 83(Suppl 2):e160–e168. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1722929

Hannan CJ, Nolan D, Corr P et al (2022) Sinonasal outcomes associated with the use of BioGlue in endoscopic transsphenoidal pituitary surgery. Neurosurg Rev 45(3):2249–2256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-021-01723-x

Hughes MA, Culpin E, Darley R et al (2020) Enhanced recovery and accelerated discharge after endoscopic transsphenoidal pituitary surgery: safety, patient feedback, and cost implications. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 162(6):1281–1286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-020-04282-0

Le PT, Soler ZM, Jones R, Mattos JL, Nguyen SA, Schlosser RJ (2018) Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of SNOT-22 Outcomes after Surgery for Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 159(3):414–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599818773065

Little AS, Jahnke H, Nakaji P, Milligan J, Chapple K, White WL (2012) The anterior skull base nasal inventory (ASK nasal inventory): a clinical tool for evaluating rhinological outcomes after endonasal surgery for pituitary and cranial base lesions. Pituitary 15(4):513–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-011-0358-4

McLaughlin N, Eisenberg AA, Cohan P, Chaloner CB, Kelly DF (2013) Value of endoscopy for maximizing tumor removal in endonasal transsphenoidal pituitary adenoma surgery. J Neurosurg 118(3):613–620. https://doi.org/10.3171/2012.11.JNS112020

Novák V, Hrabálek L, Hoza J, Hučko C, Pohlodek D, Macura J (2021) Sinonasal quality of life in patients after an endoscopic endonasal surgery of a sellar tumour. Sci Rep 11(1):23351. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02747-5

Raikundalia MD, Huang RJ, Chan L, et al. (2021) Olfactory-Specific Quality of Life Outcomes after Endoscopic Endonasal Surgery of the Sella. Allergy Rhinol (Providence). 12(no pagination). https://doi.org/10.1177/21526567211045041

Rimmer RA, Vimawala S, Chitguppi C et al (2020) Rate of rhinosinusitis and sinus surgery following a minimally destructive approach to endoscopic transsphenoidal hypophysectomy. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 10(3):405–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22482

Sarris CE, Little AS, Kshettry VR et al (2021) Assessment of the Validity of the Sinonasal Outcomes Test-22 in Pituitary Surgery: A Multicenter Prospective Trial. Laryngoscope 131(11):E2757–E2763. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29711

Scagnelli RJ, Patel V, Peris-Celda M, Kenning TJ, Pinheiro-Neto CD (2019) Implementation of Free Mucosal Graft Technique for Sellar Reconstruction After Pituitary Surgery: Outcomes of 158 Consecutive Patients. World Neurosurg 122:e506–e511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.10.090

Schreiber A, Bertazzoni G, Ferrari M et al (2019) Nasal morbidity and quality of life after endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery: a single-center prospective study. World Neurosurg 123:e557–e565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.11.212

Serra C, Staartjes VE, Maldaner N et al (2020) Assessing the surgical outcome of the “chopsticks” technique in endoscopic transsphenoidal adenoma surgery. Neurosurg 48(6):E15. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.3.FOCUS2065

van der Meulen M, Verstegen MJT, Lobatto DJ et al (2022) Impact of patient-reported nasal symptoms on quality of life after endoscopic pituitary surgery: a prospective cohort study. Pituitary 25(2):308–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-021-01199-4

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rutwik Hegde, Vlad Prodan, Karolina Futera, Iain Hathorn, Rohit Gohil and Mark Hughes contributed to the study concept and design. Rutwik Hegde and Vlad Prodan contributed to the acquisition of the data. Rutwik Hegde, Vlad Prodan and Mark Hughes contributed to the analysis of the data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Rutwik Hegde, Vlad Prodan and Karolina Futera. Rutwik Hegde, Vlad Prodan, Karolina Futera, Iain Hathorn, Rohit Gohil and Mark Hughes subsequently contributed to finalising the manuscript. The corresponding author is Rutwik Hegde.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The NHS Lothian Caldicott Guardian issued approval for prospective data collection and database maintenance. The project was approved via the University of Edinburgh undergraduate ethical sign off process.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hegde, R., Prodan, V., Futera, K. et al. Exploring the influence of nasal morbidity on quality of life following endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery: a retrospective cohort study of 95 patients. Neurosurg Rev 47, 13 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-023-02240-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-023-02240-9