Abstract

Background

It is unknown if gastric adenocarcinoma survivors have longer, shorter, or similar survival compared to the background population. This knowledge could contribute to evidence-based monitoring strategies, healthcare recommendations, and information for patients and families.

Methods

This population-based cohort study included all patients who underwent gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma between 2006–2015 in Sweden and survived ≥ 5 years after surgery. They were followed up until death, postoperative year 10, or end of study period (31 December, 2020). Division of the observed by the expected survival yielded relative survival rates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the life table method. The expected survival was derived from the entire Swedish population of the corresponding age, sex, and calendar year. Data came from medical records and nationwide registers.

Results

The survival among all 767 gastric adenocarcinoma survivors was shorter than the expected. The reduction in relative survival increased for each follow-up year, from 97.3% (95% CI 95.4–99.1%) year 6 to 86.6% (95% CI 82.3–90.9%) year 10. The decline in relative survival was more pronounced among patients who had gastrectomy in earlier calendar years (82.9% [95% CI 77.4–88.4%] year 10 for years 2011–2015), shorter education (85.2% [95% CI 77.4–93.0%] year 10 for education ≤ 9 years), more comorbidities (78.0% [95% CI 63.9–92.0%] year 10 for Charlson comorbidity score ≥ 2), and no neoadjuvant therapy (83.2% [95% CI 77.4–89.0%] year 10).

Conclusion

Gastric adenocarcinoma survivors seem to have poorer survival than the corresponding background population, particularly in certain subgroups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastric adenocarcinoma (90–95% of all gastric malignancies) carries a poor prognosis with a 5-year overall survival rate of 20–40% [1]. The survival has improved during the last decades, resulting in an increasing number of cancer survivors [1, 2]. Most tumour recurrences occur within 1–3 years after curatively intended gastrectomy and almost all deaths due to recurrences have occurred within 5 years of surgery [3]. Thus, patients who have survived beyond 5 years may be considered cured [3], and routine clinical follow-up is typically discontinued [4, 5]. There is limited evidence regarding how these cancer survivors should be managed by healthcare, advised for the future, and about the expected long-term survival for the patients and their families [6].

This study was initiated after a patient involvement meeting, during which a cancer survivor asked about his long-term survival prospects compared to other people in the population of his age now that he was cured of the cancer. Survivors of gastric adenocarcinoma may have a longer life expectancy because they were selected for surgery due to better general health and fitness [7]. A reduced life expectancy is also possible because some risk factors for gastric adenocarcinoma, e.g., tobacco smoking [8], obesity [9], and dietary factors [10, 11], increase the risk of other lethal conditions, and the cancer treatment could lead to severe sequelae and diseases [12]. One recent study indicated worse survival among gastric cancer survivors than the background population [13], but had some methodological concerns.

With this study, we aimed to help clarify if the survival among survivors of gastric adenocarcinoma is different from the corresponding background population.

Methods

Design

This nationwide and population-based cohort study included all patients in Sweden who had undergone gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma from 2006 to 2015 and had survived for at least 5 years after gastrectomy. The patients were followed up for between 6 and 10 postoperative years after the gastrectomy. The observed survival among the gastric adenocarcinoma survivors was compared to the expected survival, which was derived from the entire Swedish background population of the same age, sex, and calendar year. Data came from medical records and nationwide registers. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (2017/141–31/2).

Study cohort

The study cohort originated from the Swedish Gastric Cancer Surgery Study (SWEGASS). A detailed description of SWEGASS has been published previously [14]. In brief, SWEGASS includes at least 98% of all patients in Sweden who underwent gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma between 2006 and 2015. Patients were identified in the national Swedish Cancer Register [15] and the Swedish National Patient Register [16]. These registers have nearly 100% completeness for the recording of gastric adenocarcinoma and gastrectomy [15, 16]. Medical records were reviewed of all patients identified from the registers. Patients who died within 5 years of gastrectomy were excluded.

Comparison cohort

The comparison cohort comprised the entire Swedish population of the same age, sex, and calendar year as the participants in the study cohort. Data on the entire population were acquired from the Swedish Register of the Total Population, which includes all Swedish residents [17].

Outcome

The study outcome was relative survival. The gastric adenocarcinoma survivors were followed up from the start of year 6 to the end of year 10 after the gastrectomy, until death or end of study period (31 December, 2020), whichever occurred first. Mortality data came from the Swedish Cause of Death Register, which is 100% complete for date of death [17, 18].

Covariates

The following eight covariates, with categorizations in brackets, were included in the analyses: Age (< 66, 66–74, 75–81, or > 81 years at the start of follow-up), sex (male or female), calendar period (2011–2015 or 2016–2020 at the start of follow-up), education level (≤ 9, 10–12, or ≥ 13 years of formal education), comorbidity (0, 1, or ≥ 2 scores according to the Charlson comorbidity index at the date of gastrectomy, not counting the gastric adenocarcinoma), neoadjuvant therapy (no or yes), tumour sub-location in the stomach (cardia or non-cardia), and pathological tumour stage (0-I, II, or III-IV, according to the 8th edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] Cancer Staging Manual [19]). The medical records provided information on age, sex, calendar year, neoadjuvant therapy, tumour sub-location, and pathological tumour stage. Data on years of formal education were retrieved from the Longitudinal Integrated Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies (LISA) [20]. Comorbidities were retrieved from the Swedish National Patient Register and were classified according to the most well-validated version of the Charlson comorbidity index scoring system [21, 22].

Statistical analysis

The cumulative relative survival was calculated by dividing the cumulative observed survival in the gastric adenocarcinoma survivor group with the cumulative expected survival, derived from the corresponding background population. The observed survival within the interval j \(({P}_{j}^{O})\) was calculated by one minus the ratio of the number of cases dying during the interval j \(({D}_{j})\) to the number of cases alive at the beginning of the interval j \(({L}_{j})\):\({P}_{j}^{O}=1-\frac{{D}_{j}}{{L}_{j}}\)

The cumulative observed survival for surviving the interval x \(({CP}_{X}^{O})\) was obtained by cumulatively multiplying the proportion surviving each interval: \({CP}_{X}^{O}\): \({P}_{1}^{O}*{P}_{2}^{O}*\) …\({P}_{x}^{O}\) which was defined as:

The expected survival was calculated by matching the gastric adenocarcinoma survivors to the Swedish population of the corresponding age, sex, and calendar year. All matched individuals in the Swedish population were under risk until the corresponding matched patient died or was censored. If \({\widetilde{P}}_{ij}\) is the expected survival of an individual i for surviving the interval j, then the expected survival for the interval j \(({P}_{j}^{E})\) was:

Cumulative expected survival of surviving interval x \((C{P}_{x}^{E})\) was calculated by:

For all individuals matched to the patient cohort by age, sex, and calendar year at the beginning the interval j, the average of the expected survival in the interval j was calculated for j = 1,…,x and multiplied.

Finally, the relative survival in the interval j \(({R}_{j})\) was given by:

and the cumulative relative survival of surviving the interval x \((C{R}_{x})\) was given by:

The observed and expected survival were considered to be statistically significantly different if the confidence interval of the relative survival did not include 100%. Observed and relative survival calculations were also performed for subgroups of the eight covariates, categorized as described above (‘Covariates’). The subgroup analyses were descriptive, thus no formal tests of significance were conducted between groups. In a sensitivity analysis, participants who died due to tumour recurrence of gastric adenocarcinoma were excluded. Because data were 100% complete in the main analysis and missing data were low in the subgroup analyses, we only included cases with complete data in the final analyses, i.e., used the complete case analysis strategy.

A senior biostatistician (FM) was responsible for the data management and statistical analyses. The analyses followed a detailed and pre-defined study protocol and were performed using the statistical software SAS, Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Gastric adenocarcinoma survivors

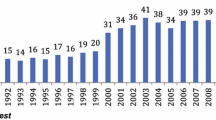

The original SWEGASS cohort included 2154 patients who had undergone gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma between 2006–2015 in Sweden. After exclusion of patients who died within 5 years of gastrectomy (n = 1387), the final study cohort included 767 gastric adenocarcinoma survivors. Characteristics of these survivors are presented in Table 1. Most participants were men, had ≤ 12 years of formal education, no serious comorbidity, no neoadjuvant therapy, non-cardia tumour, and pathological tumour stage 0-I.

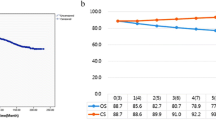

Survival in all gastric adenocarcinoma survivors

The cumulative observed survival among gastric adenocarcinoma survivors gradually decreased from 93.2% (95% CI 91.4–95.0%) at the end of postoperative year 6 to 72.2% (95% CI 68.6–75.8%) at the end of year 10 (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The cumulative relative survival decreased for each year of follow-up, from 97.3% (95% CI 95.4–99.1%) year 6 to 86.6% (95% CI 82.3–90.9%) year 10 (Table 2).

In the sensitivity analysis excluding participants who died due to tumour recurrence more than 5 years after gastrectomy (n = 34), the cumulative relative survival decreased gradually from 98.7% (95% CI 97.0–100.5%) at the end of year 6 to 90.9% (86.7–95.2%) at the end of year 10 (Supplementary Table 1).

Survival in subgroups of gastric adenocarcinoma survivors

The relative survival tended to decrease more for gastric adenocarcinoma survivors who underwent gastrectomy during earlier calendar years (82.9% [95% CI 77.4–88.4%] year 10 for the calendar years 2011–2015), had fewer years of formal education (85.2% [95% CI 77.4–93.0%] year 10 for ≤ 9 years of education), had higher Charlson comorbidity index score (78.0% [95% CI 63.9–92.0%] year 10 for scores ≥ 2), and did not receive neoadjuvant therapy (83.2% [95% CI 77.4–89.0%] year 10) (Table 3, 4, 5). There were no major differences in relative survival between subgroups of age, sex, tumour sub-location, or pathological tumour stage (Table 3, 4, 5).

Discussion

This study found that survivors of gastric adenocarcinoma have gradually poorer survival compared to the corresponding background population between 6 and 10 years after gastrectomy. The decreased relative survival was seemingly more pronounced in earlier calendar years and in participants with fewer years of education, more comorbidities, and without neoadjuvant therapy, whereas there were no obvious differences comparing subgroup of age, sex, tumour sub-location, and pathological tumour stage.

Methodological strengths of this study include the nationwide and population-based design with a high participation rate, which provided a large and unselected cohort and generalizable results. The review of all medical records and the use of high-quality nationwide registers provided accurate and nearly complete information on all variables used in the study. This study also has limitations. There was a limited number of patients remaining many years after gastrectomy. Therefore, we restricted the number of follow-up years to 10 to secure statistical power. We did not have health data on the background Swedish population, which was used as the comparison group, and thus could not assess mechanisms for the differences in survival.

One recent study based on data from the database Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) in the United States observed an increased mortality among 5-year gastric cancer survivors compared to the background population (standardized mortality ratio 1.72, 95% CI 1.66–1.77) [13]. However, that study included all types of gastric malignancies with different treatments and prognoses, did not account for late deaths due to tumour recurrence, and the study period started already in 1975 raising concerns about its relevance for healthcare of today. Nevertheless, the finding is consistent with the results of the present study. Other studies of earlier cohorts of gastric cancer survivors diagnosed many decades ago have found a relative survival around 80–90% in Western cohorts [23,24,25], i.e. consistent with the present study, and up to 97% in Japan [26, 27]. A similarly designed study on oesophageal cancer survivors in Sweden (from our group) revealed a pattern of decreased survival compared to the corresponding background population [28]. Given the anatomical proximity of the two cancer types, several shared risk factors, and similar treatment, particularly for adenocarcinomas of the gastroesophageal junction, the similar results of the present study indicate consistency.

The current study revealed that not only the entire group of gastric adenocarcinoma survivors had a decreased survival compared to the expected, but all subgroups showed a tendency of poorer survival compared to the corresponding background population, including survivors with characteristics typically associated with better long-term survival. This observation suggests that other factors play a major role. Risk factors for gastric adenocarcinoma, such as tobacco smoking, obesity, and dietary factors [10, 29], are shared with other serious conditions, and long-term consequences could arise from the surgical procedure or chemotherapy [12]. This could contribute to a higher prevalence of severe comorbidities compared to the background population. Previous studies have indicated an elevated risk of several conditions in gastric adenocarcinoma survivors when compared to the general population, including osteoporosis [30], anaemia [31], Alzheimer’s disease [32], and second primary cancers [33, 34]. Some specific causes of death are also more common among gastric cancer survivors than the general population, particularly infectious diseases, chronic liver disease, other malignancies, and renal diseases [13]. Taken together, there are several explanations for the worse survival rates found among patients having been cured of gastric adenocarcinoma compared to the background population in the present study.

The analyses indicated worse survival in some subgroups of participants. The worse survival among patients who underwent gastrectomy during earlier calendar years may be due to recent developments in diagnostic procedures and patient assessment, rendering a stricter selection of patients for surgery [35]. The lower survival in gastric adenocarcinoma survivors with less education might be due to lifestyle factors, e.g., higher exposure to tobacco smoking, overconsumption of alcohol, and obesity [8,9,10,11]. Among all subgroups analysed, the relative survival was worst among those with multiple comorbidities (Charlson comorbidity index ≥ 2), suggesting that this is the strongest risk factor for mortality among gastric adenocarcinoma survivors. Finally, there were lower relative survival rates among patients who did not receive neoadjuvant therapy compared to those who did. Patients who did not receive neoadjuvant therapy might have poorer general health and a thus lower chance of long-term survival, but research is warranted to identify the mechanisms behind this less expected observation.

In conclusion, this nationwide and population-based study found that gastric adenocarcinoma survivors have a gradually worse survival 6–10 years after gastrectomy compared to the corresponding background population, and even more so in certain subgroups. This finding underscores the relevance of closer monitoring and health-related recommendations for these individuals and provides evidence-based information regarding the expected long-term survival to these individuals and their families.

Data availability

Data not available.

References

Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, Harewood R, Matz M, Nikšić M, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000–14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1023–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)33326-3.

Anderson LA, Tavilla A, Brenner H, Luttmann S, Navarro C, Gavin AT, et al. Survival for oesophageal, stomach and small intestine cancers in Europe 1999–2007: Results from EUROCARE-5. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(15):2144–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.026.

D’Angelica M, Gonen M, Brennan MF, Turnbull AD, Bains M, Karpeh MS. Patterns of initial recurrence in completely resected gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2004;240(5):808–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000143245.28656.15.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2021 (6th edition). Gastric Cancer. 2023;26(1):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-022-01331-8.

Ajani JA, D’Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Chao J, Cooke D, Corvera C, et al. Gastric cancer version 2.2022 NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(2):167–92. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2022.0008.

Lordick F, Carneiro F, Cascinu S, Fleitas T, Haustermans K, Piessen G, et al. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(10):1005–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2022.07.004.

Gertsen EC, Brenkman HJF, Brosens LAA, Luijten J, Mohammad NH, Verhoeven RHA, et al. Refraining from resection in patients with potentially curable gastric carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(5):1062–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2020.10.025.

Trédaniel J, Boffetta P, Buiatti E, Saracci R, Hirsch A. Tobacco smoking and gastric cancer: review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 1997;72(4):565–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970807)72:4%3c565::aid-ijc3%3e3.0.co;2-o.

Chen Y, Liu L, Wang X, Wang J, Yan Z, Cheng J, et al. Body mass index and risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of a population with more than ten million from 24 prospective studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(8):1395–408. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-13-0042.

Thrift AP, Wenker TN, El-Serag HB. Global burden of gastric cancer: epidemiological trends, risk factors, screening and prevention. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20(5):338–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00747-0.

Tsugane S, Sasazuki S. Diet and the risk of gastric cancer: review of epidemiological evidence. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10(2):75–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-007-0420-0.

Shapiro CL. Cancer survivorship. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2438–50. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1712502.

Lou T, Hu X, Lu N, Zhang T. Causes of death following gastric cancer diagnosis: a population-based analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2023. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.939848.

Asplund J, Gottlieb-Vedi E, Leijonmarck W, Mattsson F, Lagergren J. Prognosis after surgery for gastric adenocarcinoma in the Swedish Gastric Cancer Surgery Study (SWEGASS). Acta Oncol. 2021;60(4):513–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186x.2021.1874619.

Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, Talbäck M. The completeness of the Swedish cancer register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(1):27–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860802247664.

Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-450.

Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AK, Ljung R, Michaëlsson K, Neovius M, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(2):125–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0117-y.

Brooke HL, Talbäck M, Hörnblad J, Johansson LA, Ludvigsson JF, Druid H, et al. The Swedish cause of death register. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(9):765–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0316-1.

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, et al. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93–9. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21388.

Ludvigsson JF, Svedberg P, Olén O, Bruze G, Neovius M. The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(4):423–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00511-8.

Brusselaers N, Lagergren J. The charlson comorbidity index in registry-based research. Methods Inf Med. 2017;56(5):401–6. https://doi.org/10.3414/me17-01-0051.

Armitage JN, van der Meulen JH. Identifying co-morbidity in surgical patients using administrative data with the Royal College of Surgeons Charlson Score. Br J Surg. 2010;97(5):772–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.6930.

Janssen-Heijnen ML, Gondos A, Bray F, Hakulinen T, Brewster DH, Brenner H, Coebergh JW. Clinical relevance of conditional survival of cancer patients in Europe: age-specific analyses of 13 cancers. J Clin Oncoly. 2010;28(15):2520–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9697.

Janssen-Heijnen ML, Houterman S, Lemmens VE, Brenner H, Steyerberg EW, Coebergh JW. Prognosis for long-term survivors of cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(8):1408–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdm127.

Wang SJ, Emery R, Fuller CD, Kim JS, Sittig DF, Thomas CR. Conditional survival in gastric cancer: a SEER database analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:153–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-007-0424-9.

Ito Y, Miyashiro I, Ito H, Hosono S, Chihara D, Nakata-Yamada K, Nakayama M, Matsuzaka M, Hattori M, Sugiyama H, Oze I. Long-term survival and conditional survival of cancer patients in Japan using population-based cancer registry data. Cancer Sci. 2014;105(11):1480–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.12525.

Ito Y, Nakayama T, Miyashiro I, Ioka A, Tsukuma H. Conditional survival for longer-term survivors from 2000–2004 using population-based cancer registry data in Osaka, Japan. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-304.

Lundberg E, Lagergren P, Mattsson F, Lagergren J. Life Expectancy in survivors of esophageal cancer compared with the background population. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(5):2805–11. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-022-11416-4.

Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NC, Lordick F. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2020;396(10251):635–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31288-5.

Yoo SH, Lee JA, Kang SY, Kim YS, Sunwoo S, Kim BS, Yook JH. Risk of osteoporosis after gastrectomy in long-term gastric cancer survivors. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21(4):720–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-017-0777-7.

Jun JH, Yoo JE, Lee JA, Kim YS, Sunwoo S, Kim BS, Yook JH. Anemia after gastrectomy in long-term survivors of gastric cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2016;28:162–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.02.084.

Choi YJ, Shin DW, Jang W, Lee DH, Jeong SM, Park S, et al. Risk of dementia in gastric cancer survivors who underwent gastrectomy: a Nationwide Study in Korea. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(13):4229–37. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07913-8.

Hiyama T, Hanai A, Fujimoto I. Second primary cancer after diagnosis of stomach cancer in Osaka. Japan Jpn J Cancer Res. 1991;82(7):762–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.1991.tb02700.x.

Lundegårdh G, Hansson LE, Nyrén O, Adami HO, Krusemo UB. The risk of gastrointestinal and other primary malignant diseases following gastric cancer. Acta Oncol. 1991;30(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/02841869109091804.

Asplund J, Kauppila JH, Mattsson F, Lagergren J. Survival trends in gastric adenocarcinoma: a population-based study in Sweden. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(9):2693–702. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6627-y.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society, and the Stockholm Cancer Society.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. Swedish Research Council (2019-00209), Swedish Cancer Society (21 1489), and Stockholm Cancer Society (201163). Vetenskapsrådet,2019-00209,Jesper Lagergren,Cancerfonden,21 1489,Jesper Lagergren,Radiumhemmets Forskningsfonder,201163,Jesper Lagergren

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leijonmarck, W., Mattsson, F. & Lagergren, J. Survival among patients cured from gastric adenocarcinoma compared to the background population. Gastric Cancer (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-024-01545-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-024-01545-y