Abstract

Background

Oncologic outcomes after laparoscopic gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer in the West have been poorly investigated. The aim of the present study was to compare survival outcomes in patients undergoing curative-intent laparoscopic and open gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer in several centres belonging to the Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer.

Methods

Data of patients operated between 2015 and 2018 were retrospectively analysed. Propensity Score Matching was performed to balance baseline characteristics of patients undergoing laparoscopic and open gastrectomy. The primary endpoint was 3-year overall survival. Secondary endpoints were 3-year disease-free survival and short-term outcomes. Multivariable regression analyses for survival were conducted.

Results

Data were retrieved from 20 centres. Of the 717 patients included, 438 patients were correctly matched, 219 per group. The 3-year overall survival was 73.6% and 68.7% in the laparoscopic and open group, respectively (p = 0.40). When compared with open gastrectomy, laparoscopic gastrectomy showed comparable 3-year disease-free survival (62.8%, vs 58.9%, p = 0.40), higher rate of return to intended oncologic treatment (56.9% vs 40.2%, p = 0.001), similar 30-day morbidity/mortality. Prognostic factors for survival were ASA Score ≥ 3, age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥ 5, lymph node ratio ≥ 0.15, p/ypTNM Stage III and return to intended oncologic treatment.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer offers similar rates of survival when compared to open gastrectomy, with higher rates of return to intended oncologic treatment. ASA score, age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index, lymph node ratio, return to intended oncologic treatment and p/ypTNM Stage, but not surgical approach, are prognostic factors for survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common malignancy and the second cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide [1, 2]. Its incidence and characteristics vary between East and West; in particular, Western patients are more frequently older, with higher BMI, and affected by an advanced disease at diagnosis [3, 4]. During the last decades, several types of perioperative and adjuvant approaches have been introduced, resulting in prolonged survival and less recurrence [5, 6]; however, surgical resection aiming at free margins and adequate lymphadenectomy still remain the only potentially curative therapy for advanced gastric cancer (AGC).

Since the first report by Kitano in 1994 [7], minimally invasive surgical approach has gained attention as an alternative option to the traditional open approach for the treatment of gastric cancer, due to its potential advantages which include less blood loss, reduced postoperative pain, faster recovery and reduced hospital stay [8,9,10,11]. At the beginning, laparoscopic approach was reserved for distal gastrectomy (DG), but thanks to improvements in surgical instruments and technical skills, it has been gradually adopted for total gastrectomy (TG) [12].

Laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG) clearly showed its safety and effectiveness for the treatment of Early Gastric Cancer, demonstrating better short-term outcomes without worsening oncological ones in comparison to open gastrectomy (OG) [13, 14]. More recently, encouraging results emerged regarding the minimally invasive surgical treatment of AGC [8, 9]. The majority of high-quality studies investigating the role of LG in the treatment of AGC come from Eastern countries [15], while there is a lack of data regarding survival outcomes after LG of Western patients.

The aim of the present study was to compare survival outcomes in patients undergoing curative-intent LG and OG for AGC in several national centres belonging to the Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer (GIRCG) [16].

Materials and methods

Study overview

Data of consecutive patients operated on between January 2015 and May 2018 were retrospectively retrieved from several Italian centres belonging to the GIRGC network. All participating centres received a specific database for data uploading with the required parameters. Data were collected locally using prospective maintained databases and gathered centrally by the study coordinators. The study protocol followed the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in Brazil 2013).

The Local Ethical Committee of the coordinating centre reviewed and approved the protocol (no. 454-30,072,020). Study results were reported according to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statements.

Population of the study

Women and men patients who underwent OG and LG with curative-intent.

Inclusion criteria:

-

Age from over 18 years old;

-

ASA (American Society of Anesthesiology) score < 4;

-

Primary, histologically confirmed gastric carcinoma of the upper, middle, lower stomach;

-

Staging cT2-4a, N0-3, M0 at preoperative evaluation according to AJCC 8th edition Cancer Staging Manual [17], performed with contrast enhanced thoraco-abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan;

-

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) performed or not performed;

-

Curative intent resection potentially achievable through DG or TG with D2 lymphadenectomy;

-

Absence of distant metastases (haematogenous, extra-regional lymph nodes (LNs)), positive peritoneal cytology on intraoperative peritoneal washing).

Exclusion criteria:

-

Tumours involving the gastro-esophageal junction and/or the duodenum;

-

Intraoperative/postoperative assessment of M1 staging, with preoperative staging M0;

-

Multivisceral resection, defined as en bloc removal of any organ or structure to which the primary tumour was found to be adherent at the moment of surgical intervention to reach surgical radicality;

-

History of previous gastrectomy, endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection;

-

History of other malignant disease within the past 3 years, except for low aggressive malignancies (e.g. basalioma);

-

History of previous chemotherapy (except NACT administered before gastrectomy) and/or radiotherapy within the past 3 years;

-

Patients lost at follow-up within 3 years from the indexed operation.

Variables and definitions

Except for a few cases in which laparoscopic treatment would not have been feasible (important peritoneal adhesions, impossibility to maintain pneumoperitoneum), according to the selection criteria for the current study, all selected patients could have undergone both open and laparoscopic gastrectomy, based on surgeon’s decision. The overall number of patients undergoing gastrectomy with curative-intent for malignancy between 2015 and 2018 in each institution was recorded and expressed in terms of annual caseload (gastrectomies/year); a cut-off of 31 gastrectomies/year was chosen to define high-volume centres [18].

Clinico-pathological variables included sex, age, body mass index (BMI), ASA Score, age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (aCCI), Performance Status according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncologic Group (ECOG-PS), previous abdominal surgery, tumour site, cTNM Stage according to the 8th edition of the AJCC Staging System [17], type of intervention (TG or DG), lymph node ratio (LNR, defined as the ratio between positive LNs and the total number of retrieved LNs) [19], performed NACT (defined as any chemotherapy received within 8 weeks before surgery for a non-metastatic disease) and p/ypTNM Stage according to the 8th edition of the AJCC Staging System [17]. Specific continuous variables were categorised according to thresholds previously used in the literature [20].

Diagnostic work-up was performed according to GIRCG guidelines [21]. Clinical stage was defined according to the 8th edition of the AJCC Staging System (TNM) [17]. Indication to NACT was evaluated in each centre according to national and international guidelines [21, 22]. Re-staging was performed with a contrast enhanced thoraco-abdominal CT scan performed within 4 weeks after completion of NACT in order to rule out progressive disease and confirm surgical indication.

The type of surgical resection was assessed according to tumour site, JGCA and GIRGC guidelines [21, 23]. In case of LG, including either totally laparoscopic or laparoscopic-assisted gastrectomy, digestive tract reconstruction could be accomplished via a mini-laparotomy through an abdominal incision not greater than 10 cm. Any abdominal incision greater than 10 cm was classified as a conversion to open approach, as well as any need to complete the resection phase by any type of laparotomy.

Postoperative care and discharge was accomplished according to the standard practice and criteria of each surgical centre.

Pathologic stage was expressed as p/ypTNM according to the criteria of the 8th edition of the AJCC Staging System [17]. Histopathological variables collected were: tumour location, morphological type according to Lauren and WHO Classification [30], tumour size, grading, margin status, presence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) and LNR.

Indications to postoperative chemotherapy, postoperative follow-up (FU) and surveillance were accomplished in accordance with national and international recommendations [21, 22]. Oncological variables included patient status at last FU, incidence of overall recurrence (both local or distant) and return to intended oncologic treatment (RIOT) [24], defined as number of patients who received any type of postoperative adjuvant systemic chemotherapy, including either adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) and perioperative chemotherapy (PC). Overall survival (OS) was defined as the number of months from surgical intervention to death of the patient for any causes. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the number of months from surgical intervention to first diagnosis of cancer recurrence. Cancer recurrence was diagnosed on the basis of clinical, radiological, and laboratory exams after local multidisciplinary tumour board discussion; histological confirmation was indicated when a clear diagnosis could not be obtained from the aforementioned techniques.

Study endpoints

Primary endpoint was 3-year OS.

Secondary endpoints were:

-

3-year DFS;

-

postoperative morbidity, recorded at 30 days and graded according to the Clavien–Dindo (CD) classification and the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI). Severe complications were defined as CD Grade > 2. Specific complications after gastrectomy namely anastomotic leak, duodenal leak, bleeding, abdominal collections, and pancreatic fistula were recorded separately according to Baiocchi et al.[25];

-

postoperative length of stay (LOS), defined as the number of nights from surgery to discharge;

-

postoperative mortality and readmission, calculated as the number of deaths and readmissions occurring within 30 days from surgery;

-

RIOT;

-

number of harvested LNs.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were median and interquartile range for continuous variables and absolute numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Clinico-pathological patients’ characteristics were compared between treatment groups (open surgery vs laparoscopy) using Mann–Whitney test or Fisher test for continuous or categorical variables, respectively.

OS and DFS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the Log-rank test between treatment groups. Uni- and multivariable Cox regression was applied to assess the association between predetermined clinico-pathological covariates (open surgery vs laparoscopy, sex, age, BMI ≥ 25, ASA 3–4 vs 2–1, aCCI ≥ 5, previous abdominal surgery, total gastrectomy vs subtotal, LNR, p/yp TNM III vs I-II, RIOT) and the time-to-event endpoints. Multiple imputation by chained equations was applied to address the problem of missing values for BMI (19.4%) and ASA (0.4%).

A propensity score matched (PSM) analysis was carried out to assess the association between surgical approach and the outcomes in a sample where potential confounders are balanced between treatment groups. A logistic regression model was used to estimate the PS. A 1:1 matching without replacement was performed using the nearest neighbour greedy-matching algorithm with a caliper width of 0.1. Balance was checked by computing absolute standardized mean differences (SMD) between surgery groups for each covariate in the PS-matched sample. A SMD threshold of 0.1 was considered to detect substantial imbalance [26]. OS and DFS Kaplan–Meier curves by surgery approach were estimated and compared in the matched population. The distribution of other postoperative outcomes was also compared between matched treatment groups. R software version 4.1.2 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

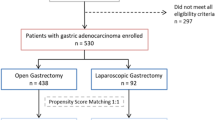

A CONSORT Diagram reporting the overall number of patients treated in the study period and the number of patients excluded according to exclusion criteria is provided in supplementary Fig. 1. During the study period, 717 patients met the inclusion criteria and were considered for the analysis. Data were retrieved from 20 Italian centres. The vast majority of patients (87.4%) were treated in high-volume hospitals with an annual caseload greater than 31. Of the entire cohort, 226 (31.5%) patients underwent LG and 491 (68.5%) OG. There were 283 females (39.5%) and 434 males (60.5%), with a median age of 73.0 years (IQR 64.0–78.0), a median BMI of 24.98 (IQR 22.1–27.3), and a median aCCI of 5 (IQR 4–6). Two-hundred-eighty-two patients (39.4%) had previous abdominal surgery and 159 (26.9%) patients received NACT (35.2% fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin and docetaxel; 21.4% epirubicin, cisplatin plus fluorouracil; 43.4% other chemotherapy regimens).

The two groups did not differ in terms of age, sex, aCCI, ASA Score, previous abdominal surgery, tumour site at diagnosis and accomplishment of NACT. Significant differences between the groups were found regarding median BMI (p < 0.001), cTNM Stage (p = 0.004) and p/yp TNM Stage (p < 0.001). Clinico-pathological characteristics of the unmatched cohort are summarised in Table 1.

A logistic regression model was used to estimate the propensity score (PS). Probability of LG was modelled. The variables included to create the PS were sex, age, ASA (3–4 vs 1–2), aCCI ≥ 5, previous abdominal surgery, performed NACT, type of surgical resection (DG vs TG), BMI ≥ 25, p/yp TNM (III vs I-II). Out of the 491 patients undergoing OG, 219 (44.6%) were correctly matched with 219 out of 226 patients (96.9%) who underwent LG. No significant difference was found between the matched cohorts in terms of clinico-pathological characteristics. Clinico-pathological characteristics of the matched cohort are summarised in Table 2.

Short-term outcomes

Operative, postoperative and histopathology outcomes of the matched cohort are shown in Tables 3 and 4. When compared to OG, patients who underwent LG showed a longer median operating time (242.0 vs 260.0 respectively, p = 0.007), a higher rate of Billroth II (B2) digestive reconstruction (13.7% vs 6.8%, p = 0.027) and a lower rate of combined cholecystectomy (16.9% vs 34.7%, p < 0.001). Although not significant, a shorter median LOS was found in LG patients when compared to OG (9.0 vs 10.0, respectively, p = 0.056). Conversion to laparotomy occurred in 21 patients (9.6%). No difference was found between the groups in terms of postoperative complications, gastric-specific and severe complications, 30-day mortality and readmission rates. Pathologic report showed no difference between the groups in terms of tumour histology features, number of harvested LNs, LNR and margin status. When compared to OG, LG was associated with a higher rate of RIOT (58.4% vs 43.8%, p = 0.003) and a similar rate of recurrence (29.2% vs 31.1%, p = 0.755).

Survival analysis

Median FU of the matched cohort was 40 months. The Kaplan–Meier curves (Fig. 1a, b) showed comparable 3-year OS rates between LG and OG (73.6% vs 68.7%, p = 0.40). Similarly, no difference was found between the groups in terms of 3-year DFS (62.8% vs 58.9%, p = 0.40).

The univariate analysis of the entire cohort showed that ASA Score ≥ 3, laparoscopic approach, age > 70 years, aCCI ≥ 5, previous abdominal surgery, LNR ≥ 0.15, p/ypTNM Stage III and RIOT significantly correlated with OS (p < 0.05). At Cox multivariable regression analysis, independent prognostic factors for OS were ASA Score (HR 1.372), aCCI (HR 1.143) LNR (HR 1.718), p/ypTNM Stage (HR 2.224) and RIOT (0.505). Univariable and multivariable analysis are shown in Table 5.

Survival analysis and uni-/multivariable Cox regression model for DFS of the unmatched cohort are provided as supplementary material in supplementary Fig. 2 and Table 1.

Survival analysis by surgical approach in the PS-matched cohort according pTNM/ypTNM subgroups are provided as supplementary material in supplementary Fig. 3.

Discussion

This retrospective Western study from 20 Italian centres found that there was no difference between LG and OG in terms of 3-year OS, in patients affected by AGC. In addition, short-term postoperative outcomes did not significantly differ between the groups. LG was associated with longer operating time and higher rate of RIOT.

In the last decades, several efforts have been made to improve the prognosis of patients affected by gastric cancer [27] based on both tailored treatments and careful patient selection; these have included the introduction of PC [5] and targeted therapeutic agents [22], together with the so-called conversion surgery for stage IV gastric cancer [28]. On the other hand, postoperative complications negatively affect survival outcomes [29]; ideally, laparoscopy may contribute in reducing such complications thanks to a magnified visualisation and a lower tissue trauma leading to a reduced surgical stress response [30]. Thus, LG has gained growing attention, demonstrating its advantages in terms of short-term outcomes as compared to open surgery [8, 13, 31, 32].

However, many doubts have been raised about the actual reproducibility of these results in a Western setting, since the majority of published studies come from Eastern countries in which patients usually have more favourable anthropometric and tumour characteristics when compared to Western ones [30]. The present study retrieved data from 20 Italian institutions reflecting demographic features of a Western population [3, 4]; in the overall cohort, 59% of patients were older than 70 years, more than 40% received previous abdominal surgery, 40% had a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 and 35% had a ASA score greater than or equal to 3. Moreover, unlike other studies where NACT was not performed [33], 22% of our patients received NACT, a percentage that might be explained by the inclusion of cTNM Stage I gastric cancers and the aforementioned clinical and demographic features of the patients our study cohort.

Despite the obvious difference in terms of patient characteristics, which could potentially increase the technical complexity of LG in Western countries, our study showed an acceptable conversion rate (10%) as compared with previous studies where it ranged between 3 and 14% [12, 34, 35]; this should be also evaluated considering the rate (86%) of high-volume gastric surgery centres among participants, which confirmed the feasibility of LG in centres experienced in both advanced laparoscopy and gastric cancer surgery.

As expected, in our study, LG had a longer operating time than OG, despite a higher number of cholecystectomies performed in the OG group; this was consistent with all previously published studies [8, 34,35,36]. The groups significantly differed in terms of B2 digestive reconstruction rate, that was higher in LG. Our results may reflect the surgeon’s preference in choosing a time-saving, single-anastomosis reconstruction technique in patients with old age, affected by AGC and undergoing a minimally invasive intervention [31]. Although Roux-en-Y reconstruction seems to be associated with reduced risks of remnant gastritis and bile reflux, a recent meta-analysis [37] demonstrated no difference among digestive reconstruction techniques in terms of safety.

Consistent with many papers from Eastern and Western centres [8, 36, 38], no difference was found between the groups in terms of postoperative LOS, morbidity, mortality and readmission rates, confirming the safety of LG.

Recently, LG was associated with a higher likelihood of receiving ACT [39]; consistently, in the present study, the rate of RIOT, including either ACT and PC, was higher in patients undergoing LG. Strong et al. [40] explained this effect with a more rapid postoperative recovery and a lesser occurrence of morbidities after LG in comparison with OG. However, in the present study, no differences were reported between the two groups in terms of postoperative outcomes, including postoperative complications and LOS; reflecting on this point, it is possible that short-term advantages of minimally invasive approach might be difficult to identify in a retrospective investigation. In addition, it should be noted that although an association between RIOT and laparoscopic gastrectomy has been identified, the present study was not designed to investigate a cause-and-effect relationship between these two variables.

Since its introduction in clinical practice, the main concern about LG was its oncological safety. Several studies demonstrated the technical feasibility and safety of LG in performing adequate lymphadenectomy and obtaining radical resection in patients affected by AGC [11, 36, 41, 42]. Consistently, in our study, no significant difference between the groups was found in the histopathology report, confirming that LG was able to achieve acceptable results in terms of surrogate oncological outcomes. In particular, an adequate number of LNs harvested and an acceptable R0 rate should be considered essential requirements to guarantee an adequate oncological intervention and LG seemed to ensure them correctly, as demonstrated by the similar results found between the groups.

The KLASS 01 trial reported a similar 5-year OS in patients receiving LG and OG for Stage I gastric cancer [14]. More recently, a similar result was confirmed by the CLASS-01 trial which demonstrated the non-inferiority of LG in comparison to OG in terms of 3-year DFS and 3-year OS (76.5% vs 77.8%, p 0.59 and 83.1% vs 85.2%, p 0.28 in LG and OG, respectively), in patients affected by AGC [43]. Moreover, a PSM analysis from the International Study Group on Minimally Invasive Surgery for Gastric Cancer Registry reported a similar 5-year OS rate between LG and OG (77.4% vs 75.2%, respectively, p = 0.229) [44]. However, these data refer mainly to Eastern patients and their reproducibility in a Western setting is still controversial with only few studies addressing this topic, reporting small sample size [45] and critical selection bias [46]. Interesting results were recently provided by a retrospective multicentric case-series [35], which analysed survival outcomes in patients affected by stage II and III gastric cancer undergoing LG, reporting a 5-year OS rate of 63%; unfortunately the long time interval of the study, the lack of a control group and the absence of a common research network between the participating centres impose caution on the interpretation of this result. In the current study, survival analysis showed similar 3-year OS (73.6% vs 68.7%, p = 0.4 in LG and OG, respectively) and DFS (62.8% vs 58.9%, p 0.4 in LG and OG, respectively) between LG and OG. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large multicentre Western study to report comparable survival outcomes between LG and OG for treatment of AGC; all participating centres belong to the same research network (GIRCG) and share the same guidelines and protocols for pathology report, guaranteeing homogeneity and quality in the surgical treatment of patients affected by gastric cancer, in a recent time interval of study period.

On multivariable analysis RIOT, ASA score, aCCI, LNR and p/yp TNM stage were independent factor for OS, as previously reported in several investigations [19, 22, 47, 48]. Despite a higher association between LG and RIOT was observed, our investigation cannot detect a prognostic effect of LG.

This study presents some limitations. First, this was a retrospective analysis and, despite a PSM being used, many unknown confounders could have generated two unbalanced cohorts at baseline affecting outcomes. Even though all patients included in this study could ideally have undergone both LG and OG, depending on the surgeon’s preference, indications to LG could slightly differ among various centres due to different skills and experience in treating patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or with high BMI, or with previous abdominal surgery; however, these differences, inevitably due to the retrospective nature of the study, were partially balanced with the propensity score matched analysis which selected comparable groups in terms of sex, age, BMI, aCCI, ASA score, NACT administration, previous abdominal surgery, type of gastrectomy. Data about pathological tumour regression grade were not available and this may represent a limit due to its prognostic value. In addition, the p/ypTNM Stage variable, which actually is a postoperative variable, was chosen to run the matching during PSM. Considering the poor reliability of clinical staging for gastric cancer [49, 50] potentially leading to a disease understaging and thus generating imbalanced cohorts at baseline, the inclusion of postoperative variables, as already documented in the gastric cancer literature [44, 51, 52], could provide better chance of achieving balanced groups at baseline, taking into account the primary endpoint. Lastly, due to the heterogeneity in the proportion of patients undergoing LG in each participating centre, the inclusion of the “centre volume” variable in PSM was considered not feasible. As previously adopted in several fields of surgery [44, 53, 54], the unfeasibility to include the “centre volume” variable is a common issue in multicentric investigations comparing different surgical approaches using PSM analysis.

Conclusions

This PSM study showed that LG for AGC offered similar survival and short-term outcomes when compared to OG, with a higher rate of RIOT. RIOT, age, aCCI, LNR and p/ypTNM Stage, but not surgical approach, were prognostic factors for survival. Future RCTs focusing on Western populations are needed to further clarify the actual role of minimally invasive curative-intent surgery in AGC.

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86.

Sitarz R, Skierucha M, Mielko J, Offerhaus J, Maciejewski R, Polkowski W. Gastric cancer: epidemiology, prevention, classification, and treatment. Cancer Manag Res. 2018. https://doi.org/10.2147/cmar.s149619.

Griffin SM. Gastric cancer in the East: same disease, different patient. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1055–6.

Dicken BJ, Bigam DL, Cass C, Mackey JR, Joy AA, Hamilton SM. Gastric adenocarcinoma: review and considerations for future directions. Ann Surg. 2005;241:27–39.

Al-Batran S-E, Homann N, Pauligk C, Goetze TO, Meiler J, Kasper S, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): a randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Elsevier BV. 2019;393:1948–57.

Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, Kinoshita T, Fujii M, Nashimoto A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1810–20.

Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146–8.

Lee H-J, Hyung WJ, Yang H-K, Han SU, Park Y-K, An JY, et al. Short-term outcomes of a multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy to open distal gastrectomy for locally advanced gastric cancer (KLASS-02-RCT). Ann Surg. 2019;270:983–91.

Huang C, Liu H, Hu Y, Sun Y, Su X, Cao H, et al. Laparoscopic vs open distal gastrectomy for locally advanced gastric cancer: five-year outcomes from the CLASS-01 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2022;157:9–17.

Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Kakisako K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Adachi Y. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth-I gastrectomy (LADG) for cancer: our 10 years’ experience. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;12:204–7.

van der Wielen N, Straatman J, Daams F, Rosati R, Parise P, Weitz J, et al. Open versus minimally invasive total gastrectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: results of a European randomized trial. Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:258–71.

Wang W, Zhang X, Shen C, Zhi X, Wang B, Xu Z. Laparoscopic versus open total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an updated meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e88753.

Katai H, Mizusawa J, Katayama H, Takagi M, Yoshikawa T, Fukagawa T, et al. Short-term surgical outcomes from a phase III study of laparoscopy-assisted versus open distal gastrectomy with nodal dissection for clinical stage IA/IB gastric cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG0912. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:699–708.

Kim H-H, Han S-U, Kim M-C, Kim W, Lee H-J, Ryu SW, et al. Effect of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy vs open distal gastrectomy on long-term survival among patients with stage I gastric cancer: the KLASS-01 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:506–13.

Beyer K, Baukloh A-K, Kamphues C, Seeliger H, Heidecke C-D, Kreis ME, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for locally advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17:68.

De Manzoni G, Roviello F, Siquini W. Surgery in the multimodal management of gastric cancer. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media; 2012.

Institute NC, National Cancer Institute. AJCC cancer staging manual 8th Edition. Definitions. 2020. https://doi.org/10.32388/b30ldk

Claassen YHM, van Sandick JW, Hartgrink HH, Dikken JL, De Steur WO, van Grieken NCT, et al. Association between hospital volume and quality of gastric cancer surgery in the CRITICS trial. Br J Surg. 2018;105:728–35.

Marchet A, Mocellin S, Ambrosi A, Morgagni P, Garcea D, Marrelli D, et al. The ratio between metastatic and examined lymph nodes (N ratio) is an independent prognostic factor in gastric cancer regardless of the type of lymphadenectomy: results from an Italian multicentric study in 1853 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245:543–52.

Lombardi PM, Mazzola M, Achilli P, Aquilano MC, De Martini P, Curaba A, et al. Prognostic value of pathological tumor regression grade in locally advanced gastric cancer: new perspectives from a single-center experience. J Surg Oncol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.26391.

De Manzoni G, Marrelli D, Baiocchi GL, Morgagni P, Saragoni L, Degiuli M, et al. The Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer (GIRCG) guidelines for gastric cancer staging and treatment: 2015. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:20–30.

Ajani J, D’Amico T, Bentrem D, Chao J, Corvera C, Al PD et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Gastric Cancer. 2020.

Association JGC, Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition). Gastric Cancer. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-020-01042-y

Aloia TA, Zimmitti G, Conrad C, Gottumukalla V, Kopetz S, Vauthey J-N. Return to intended oncologic treatment (RIOT): a novel metric for evaluating the quality of oncosurgical therapy for malignancy. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:107–14.

Baiocchi GL, Giacopuzzi S, Marrelli D, Reim D, Piessen G, Matosda Costa P, et al. International consensus on a complications list after gastrectomy for cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22:172–89.

Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:3083–107.

de Manzoni G, Roviello F. Gastric cancer: the 25-year R-evolution. Springer Nature; 2021.

Yoshida K, Yamaguchi K, Okumura N, Tanahashi T, Kodera Y. Is conversion therapy possible in stage IV gastric cancer: the proposal of new biological categories of classification. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:329–38.

Song JH, Lee S, Choi S, Cho M, Kwon IG, Kim YM, et al. Adverse prognostic impact of postoperative complications after gastrectomy for patients with stage II/III gastric cancer: analysis of prospectively collected real-world data. Front Oncol Front. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.611510.

Mazzola M, Giani A, Crippa J, Morini L, Zironda A, Bertoglio CL, et al. Totally laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: comparison between early and late phase of an initial single-center learning curve. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2021;12:688–98.

Liu F, Huang C, Xu Z, Su X, Zhao G, Ye J, et al. Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic vs open total gastrectomy for clinical stage I gastric cancer: the CLASS02 multicenter randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1590–7.

Hyung WJ, Yang H-K, Han S-U, Lee Y-J, Park J-M, Kim JJ, et al. A feasibility study of laparoscopic total gastrectomy for clinical stage I gastric cancer: a prospective multi-center phase II clinical trial, KLASS 03. Gastric Cancer. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-018-0864-4.

Hyung WJ, Yang H-K, Park Y-K, Lee H-J, An JY, Kim W, et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for locally advanced gastric cancer: the KLASS-02-RCT randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3304–13.

Cai J, Wei D, Gao CF, Zhang CS, Zhang H, Zhao T. A Prospective randomized study comparing open versus laparoscopy-assisted D2 radical gastrectomy in advanced gastric cancer. DSU Karger Publishers. 2011;28:331–7.

Bracale U, Merola G, Pignata G, Andreuccetti J, Dolce P, Boni L, et al. Laparoscopic gastrectomy for stage II and III advanced gastric cancer: long-term follow-up data from a Western multicenter retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08505-y.

van der Veen A, Brenkman HJF, Seesing MFJ, Haverkamp L, Luyer MDP, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer (LOGICA): a multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:978–89.

Lombardo F, Aiolfi A, Cavalli M, Mini E, Lastraioli C, Panizzo V, et al. Techniques for reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for cancer: updated network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02411-6.

Hu Y, Huang C, Sun Y, Su X, Cao H, Hu J, et al. Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic versus open D2 distal gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1350–7.

Kelly KJ, Selby L, Chou JF, Dukleska K, Capanu M, Coit DG, et al. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma in the west: a case–control study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4381-y.

Russo A, Strong VE. Minimally invasive surgery for gastric cancer in USA: current status and future perspectives. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:38.

Inaki N, Etoh T, Ohyama T, Uchiyama K, Katada N, Koeda K, et al. A multi-institutional, prospective, phase II feasibility study of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for locally advanced gastric cancer (JLSSG0901). World J Surg. 2015;39:2734–41.

Best LMJ, Mughal M, Gurusamy KS. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:1CD011389.

Yu J, Huang C, Sun Y, Su X, Cao H, Hu J, et al. Effect of laparoscopic vs open distal gastrectomy on 3-year disease-free survival in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer: the CLASS-01 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:1983–92.

Trastulli S, Desiderio J, Lin J-X, Reim D, Zheng C-H, Borghi F, et al. Laparoscopic compared with open D2 gastrectomy on perioperative and long-term, stage-stratified oncological outcomes for gastric cancer: a propensity score-matched analysis of the IMIGASTRIC database. Cancers. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13184526.

Garbarino GM, Costa G, Laracca GG, Castagnola G, Mercantini P, Di Paola M, et al. Laparoscopic versus open distal gastrectomy for locally advanced gastric cancer in middle-low-volume centers in Western countries: a propensity score matching analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2020;405:797–807.

Orsenigo E, Di Palo S, Tamburini A, Staudacher C. Laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a monoinstitutional Western center experience. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:140–5.

Rosa F, Tortorelli AP, Quero G, Galiandro F, Fiorillo C, Sollazzi L, et al. The impact of preoperative ASA-physical status on postoperative complications and long-term survival outcomes in gastric cancer patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:7383–90.

GASTRIC (Global Advanced/Adjuvant Stomach Tumor Research International Collaboration) Group, Paoletti X, Oba K, Burzykowski T, Michiels S, Ohashi Y, et al. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:1729–37.

Mocellin S, Pasquali S. Diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) for the preoperative locoregional staging of primary gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;CD009944.

Kim SH, Kim JJ, Lee JS, Kim SH, Kim BS, Maeng YH, et al. Preoperative N staging of gastric cancer by stomach protocol computed tomography. J Gastric Cancer. 2013;13:149–56.

Ramos MFKP, Pereira MA, Dias AR, Ribeiro U Jr, Zilberstein B, Nahas SC. Laparoscopic gastrectomy for early and advanced gastric cancer in a western center: a propensity score-matched analysis. Updates Surg. 2021;73:1867–77.

Obama K, Kim Y-M, Kang DR, Son T, Kim H-I, Noh SH, et al. Long-term oncologic outcomes of robotic gastrectomy for gastric cancer compared with laparoscopic gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:285–95.

Klompmaker S, van Hilst J, Wellner UF, Busch OR, Coratti A, D’Hondt M, et al. Outcomes after minimally-invasive versus open pancreatoduodenectomy: a pan-european propensity score matched study. Ann Surg. 2020;271:356–63.

van der Poel MJ, Barkhatov L, Fuks D, Berardi G, Cipriani F, Aljaiuossi A, et al. Multicentre propensity score-matched study of laparoscopic versus open repeat liver resection for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg Oxf Acad. 2019;106:783–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Matteo Locatelli for his initial contribution to data analysis. The following investigators of the Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer (GIRCG) also participated in this study and are to be considered as co-authors: Agnes A, Alfieri S, Alloggio M, Bencivenga M, Benedetti M, Bottari A, Cianchi F, Cocozza E, Dalmonte G, De Martini P, De Pascale S, Desio M, Emiliani G, Ercolani G, Galli F, Garosio I, Giani A, Gualtierotti M, Marano L, Morgagni P, Peri A, Puccetti F, Reddavid R, Uccelli M.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent to be included in the study, or the equivalent, was obtained from all patients.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The members of the Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer (GIRCG) are listed in acknowledgements section.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lombardi, P.M., Bernasconi, D., Baiocchi, G. et al. Open versus laparoscopic gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a propensity score matching analysis of survival in a western population—on behalf of the Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer. Gastric Cancer 25, 1105–1116 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-022-01321-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-022-01321-w