Abstract

Burning mouth syndrome is a chronic condition, which is characterised by a burning sensation or pain in the mucosa of the oral cavity. Treatment options include antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, analgesics, hormone replacement therapies and more recently photobiomodulation. This study aims to perform a systematic review with meta-analysis in order to determine the effect of photobiomodulation on pain relief and the oral health-related quality of life associated with this condition. A bibliographical search of the Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science and Scopus databases was conducted. Only randomised clinical trials were included. Pain and quality of life were calculated as mean difference and pooled at different treatment points (baseline = T0 and final time point = Tf) and laser modality. From a total of 103 records, 7 articles were retrieved for inclusion. PBM group had a greater decrease in pain than control group at Tf with a mean difference = − 2.536 (IC 95% − 3.662 to − 1.410; I2 = 85.33%, p < 0.001). An improvement in oral health-related quality of life was observed in both groups, although this was more significant in the photobiomodulation group mean difference = − 5.148 (IC 95% − 8.576 to − 1.719; I2 = 84.91%, p = 0.003). For the red laser, a greater improvement than infrared was observed, in pain, mean difference = − 2.498 (IC 95% − 3.942 to − 1.053; I2 = 79.93%, p < 0.001), and in quality of life, mean difference = − 8.144 (IC 95% − 12.082 to − 4.206; I2 = 64.22%, p = 0.027). Photobiomodulation, in particular, red laser protocols, resulted in improvement in pain and in quality of life of burning mouth syndrome patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The “International Headache Society” (IHS) defines burning mouth syndrome (BMS) as a chronic condition, which is characterised by a burning sensation or pain in the mucosa of the oral cavity. In clinical terms, the mucosa appears healthy without any obvious lesions, and this condition may be accompanied by xerostomia and/or dysgeusia. The sensation is recurrent on a daily basis, for more than 2 h/day, and for more than 3 months [1, 2]. The intensity of which ranges from moderate to severe, with it increasing throughout the day, although it tends to be absent at night. The tongue is the most affected area, followed by the lower lip and the hard palate [3, 4]. This sensation often persists for years and is the main cause of a decreased oral health-related quality of life (OHRQL) in patients with BMS [5].

Its prevalence is low, affecting between 0.1 and 3.7% of the general population [6], affects more women (1.15%) than it does men (0.38%), predominantly perimenopausal and/or postmenopausal women [7,8,9]. For some time, there have been indications that BMS affects people with personalities that are susceptible to anxiety and depression [6, 10, 11] more than those who do not experience such issues. It is a complex disease, and several pathophysiological mechanisms have been described that explain the condition [12, 13] of which the following are particularly worth mentioning: (i) alteration in dopaminergic transmission at a central level. In fact, the dopaminergic blink reflex is exaggerated in some patients with BMS [14]. (ii) Some type of peripheral neuropathy of the cranial nerves [14] given that neurophysiological and neuropathological studies have shown a loss of small diameter nerve fibres in the lingual epithelium [15], resulting to the depletion of neuroprotective steroids that alter the brain network related to mood and pain modulation [4, 16]. Which could explain the thermal and painful sensitivity in the tongue in these patients, as well as an increase in certain taste detection thresholds [17]. Some recent studies have suggested that, although not clinically visible, inflammation is the cause of the sensation of pain, with this being linked to cytokine actions [13]. Other studies have indicated that a genetic variation of the dopamine D2 receptor contributes to the sensation of pain [18]; nonetheless, mounting evidence has indicated the presence of hormonal, psychosocial, genetic and/or neuropathic causative factors [4], and, to date, final common consensus is yet to be reached.

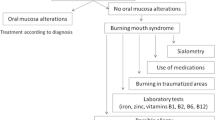

Burning symptoms not attributable to local or systemic causes are currently considered as primary or idiopathic/essential BMS [1, 4, 19]. In order to effectively manage the treatment of these patients, their full medical, clinical, and dental history must be taken and the appropriate clinical and laboratory examinations must also be performed.

Drug treatments include antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, analgesics and hormone replacement therapies. Clonazepam is the most widely used and studied drug [20], and its efficacy has been demonstrated in recent meta-analysis [21]. Other prescribed drugs include alpha-lipoic acid (ALA), gabapentin, capsaicin and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) [22, 23]. Although a wide range of medications have been administered, these are not consistently effective for the majority of patients with BMS, and less than half of patients reported symptom relief following the administration of neuropathic drug therapies. Likewise, the multiple side effects make it impossible for patients to maintain long-term treatment fidelity [24].

In recent years, the use of laser biostimulation has been proposed for the treatment of chronic and acute pain [25], and its use for patients with BMS was first described in 2010 in a pilot study however indicated that it would be necessary to further studies with a more number of cases that are mandatory to obtain statistically significant results and versus control study is necessary [26]. Photobiomodulation (PBM) is a therapy that uses light, whether LED, red or infrared, to obtain beneficial effects on cells and tissues. It has an analgesic, anti-inflammatory and biological stimulation effect, resulting in improved pain relief and tissue healing [1, 16, 27].

Current BMS management focuses on the reduction of pain and the elimination of concomitant symptoms. Another important measure that must be taken into account when assessing the impact of BMS is the OHRQL, which shows the impact that severe pain can have on the patients’ well-being and emotional state.

This study aims to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis in order to determine the effect of PBM on pain relief and the OHRQL associated with primary BMS.

Material and method

Protocol and registration

This review is an update of the review already recorded in PROSPERO (Ref. CRD42016048914), and it has been performed following the PRISMA guidelines [28] and according to the PICO method [29]: BMS patients (P = patient); PBM treatment with laser (I = intervention); laser off, or drug (C = comparison); remission of symptoms and improvement of OHRQL (O = outcome) (Fig. 1).

Eligibility criteria, data sources and research

A bibliographic search was conducted using the following keywords: “burning mouth syndrome, photobiomodulation, LLLT, treatment” in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, LiLACS, OVID, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Clinical Trials, the five regional bibliographic databases of the WHO (AIM, LILACS, IMEMR, IMSEAR, WPRIM), in order to identify relevant studies which compared the use of photobiomodulation in BMS patients to those forming a control group, describing all the types of interventions (Table 1). The search covered the first records found in the database right through to May 2021. Where necessary, the authors of the studies were contacted in order to identify missing information or data.

Inclusion criteria

Articles that addressed randomised clinical trials, which included a well-defined control group in any language: patients who presented with primary BMS, patients who reported symptoms of burning or pain in the oral mucosa for at least 3 months. In the case in which other systemic diseases were present, it was required for these to be controlled.

Exclusion criteria

Articles for which the abstract and/or full text were not available: studies with insufficient data; in vitro or animal studies; case reports or series, letters to the editor and/or editorials, literature reviews, books or book chapters, indexes and abstracts or dissertations, monographs and abstracts presented at scientific events; patients who had previously undergone radio and/or chemotherapy of the head and neck. With regard to the pain assessment, articles in which the visual analogue scale (VAS) or numerical rating scale (NRS) score was not between 0 and 10 (where 0 is no pain and 10 is excruciating pain), and/or articles that did not report “mean” and “SD” values, referring to the start and/or end of the treatment for VAS/NRS, and/or studies in which the OHRQL questionnaire used was not the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP). Studies with secondary BMS patients, whose condition was the result of organic causes, such as biological factors, that is to say, the presence of certain bacteria or fungi that have a direct irritant effect on the oral mucosa that could trigger burning symptoms, or systemic factors such as Sjögren’s syndrome, diabetes or if the medication used causes oral burning.

Study selection

Two independent researchers, MPS and GCVC, selected the studies in a two-round process. The first round included an extensive analysis of the titles and abstracts of all of the articles that were obtained in the search. Studies that were unrelated to the topic of interest, that is to say texts that did not address the treatment of BMS patients with PBM, were eliminated. Titles and abstracts that met the criteria, but for which the abstracts were not available, were subsequently analysed in the second round. In the second round, all of the eligible studies were examined in full text before a decision was made as to whether or not the eligibility criteria had been met. The references included in the eligible articles were carefully screened in order to verify any studies that had not been detected through the main search strategy. The excluded studies were recorded separately, indicating the reasons for their exclusion.

Data collection process

The full articles were read in order to determine whether the inclusion criteria had been met, and both researchers (MPS and GCVC) collected the data (in duplicate) to prevent any measurement bias. A third researcher, JLL, acted as a mediator in the case of any discrepancies, or in the case in which an agreement could not be reached. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated in order to determine the inter-researcher agreement, with a score of 0.93 [30].

Study variables

The following data was extracted from each study: first author, year of publication, country of origin, sample size and details such as gender, mean age, the type of intervention in the control group, type of laser and amount of energy applied, total number of sessions, total duration of the treatment, time of completed treatment segment, request for analyses and the method used to assess the results (pain relief by VAS/NVA (0–10) and quality of life by OHIP-14 questionnaire) (Table 2).

Quality assessment and risk of bias

The quality was assessed using the Jadad scale [31], which consists of five questions, each of which can be assigned either 0 or 1 point, covering three aspects of clinical trials: randomisation, blinding and description of loss in follow-up. The final sum of these points ranges from 0 to 5, and a score of less than 3 determines a high risk of bias. Once again, this analysis was performed independently by each of the two researchers, and if there was any disagreement, the third researcher acted as a mediator.

Statistical analysis

Statistically significant results from the quantitative analysis have been presented on “forest plot” graphs. In order to attain these results, the variables from comparable studies were collected before being analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), v. 24.0 (IBM Inc., Madrid, Spain). Results were expressed as mean difference (MD). Heterogeneity was analysed using the I2 statistic. An I2 value < 50% and p > 0.1 indicate low heterogeneity, so a fixed effect model was performed. However, when I2 > 50% and p < 0.1 indicate considerable heterogeneity, a random effect model was performed [32].

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

A total of 103 publications were obtained in the initial searches, 6 of which met the pre-specified criteria for inclusion with regard to pain assessment, and 5 which included the OHIP-14 quality of life questionnaire. Two of the publications were segregated into two independent studies (a and b) given that different laser frequencies had been used with the same protocol [33], and different protocols had been with the same laser frequency [34] in each of the study groups, compared to the same control group. A detailed description of the included studies has been provided in the study selection flow chart (Table 2).

The evaluated interventions included low-level laser therapy as a therapeutic strategy in the treatment group. The following modalities of PBM use were analysed: 630–685 nm [8, 35, 36], 810–830 nm [34, 37], which corresponded to red and infrared light respectively, or both [33, 38]. In terms of the control group, laser off was present in six of the studies [8, 33,34,35, 37, 38], and the drug, ALA [36], was applied in one study. General information, as well as the additional methods used to assess the adjuvant effects of therapy, have been summarised in Table 2.

Quality of the studies included

The quality of the studies was evaluated was using the Jadad scale, with all studies scoring greater than 3 (Table 3).

Meta-analysis

Treatment points

With regard to pain at T0, no significant differences were found amongst the different study groups. MD = − 0.336 (IC 95% − 1.157 to 0.485; p = 0.423; I2 = 78.58%, p < 0.001). When comparing the degree of pain at the final time point (Tf) between the two groups, significant differences were observed, with a greater decrease in pain observed for the PBM group with a MD = − 1.645 (IC 95% − 2.784 to − 0.507; I2 = 85.67%, p < 0.001). In addition, when we compared the Tf and the initial/baseline (T0), there was a reduction in the degree of pain in the PBM group MD = − 2.536 (IC 95% − 3.662 to − 1.410; I2 = 85.33%, p < 0.001) and in the MD control group − 1.274 (− 2.569 to 0.020; I2 = 86.81%, p = 0.054) (Fig. 2).

VAS, PBM T0 vs control T0: With regard to pain at T0, no significant differences were found amongst the different study groups. MD = − 0.336 (IC 95% − 1.157 to 0.485; p = 0.423; I2 = 78.58%, p < 0.001). VAS, PBM Tf vs control Tf: When comparing the degree of pain at the final time point (Tf) between the two groups, significant differences were observed, with a greater decrease in pain observed for the PBM group with a MD = − 1.645 (IC 95% − 2.784 to − 0.507; I2 = 85.67%, p < 0.001). VAS, T0 vs Tf of subgroups, control vs PBM: There was a reduction in the degree of pain in the PBM group MD = − 2.536 (IC 95% − 3.662 to − 1.410; I2 = 85.33%, p < 0.001) and in the MD control group − 1.274 (− 2.569 to 0.020; I2 = 86.81%, p = 0.054)

When evaluating the degree of the OHRQL at time T0, no significant differences were found between the study and control groups MD = − 1.516 (IC 95% − 3.797 to 0.485; p = 0.766; I2 = 52.54%, p < 0.193). When comparing the OHRQL at Tf between the two groups, significant differences were observed, with a greater decrease in the PBM group with a MD = − 4.193 (IC 95% − 6.280 to − 2.105; I2 60.86%, p < 0.001). Furthermore, when comparing the Tf and the T0, an improvement in OHRQL was observed in both groups, although this was more significant in the PBM group MD = − 5.148 (IC 95% − 8.576 to − 1.719; I2 = 84.91%, p = 0.003) than in the control group, MD − 4.044 (− 5.413 to − 2.676; I2 = 22%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

OHIP, PBM T0 vs control T0: When evaluating the degree of pain and the OHRQL at time T0, no significant differences were found between the study and control groups MD = − 1.516 (IC 95% − 3.797 to 0.485; p = 0.766; I2 = 52.54%, p < 0.193). OHIP, PBM Tf vs control Tf: When comparing the OHRQL at Tf between the two groups, significant differences were observed, with a greater decrease in the PBM group with a MD = − 4.193 (IC 95% − 6.280 to − 2.105; I2 60.86%, p < 0.001). OHIP, T0 vs Tf of subgroups, control vs PBM: an improvement in OHRQL was observed in both groups, more significant in the PBM group MD = − 5.148 (IC 95% − 8.576 to − 1.719; I2 = 84.91%, p = 0.003) than in the control group, MD − 4.044 (− 5.413 to − 2.676; I2 = 22%, p < 0.001)

Laser modality

With regard to the laser modality used (red/infrared), in terms of pain at T0, no differences were found between the red laser group and the control group, MD = − 0.389 (IC 95% − 2.007 to 1.229; I2 = 88.98%, p = 0.638), nor between the infrared laser group and the control group, MD = − 0.336 (IC 95% − 1.075 to 0.402; I2 = 44.37%, p = 0.372). At Tf, no significant differences were found between the red laser group and the control group, MD = − 1.555 (IC 95% − 3.569 to 0.459; I2 = 90.67%, p = 0.130); however, some differences were found between the infrared modality and the control group, MD = − 1.774 (IC 95% − 3.116 to − 0.432; I2 = 78.05%, p = 0.010). Furthermore, when we compared the Tf and the initial T0 for the red laser, an improvement in pain was observed, MD = − 2.498 (IC 95% − 3.942 to − 1.053; I2 = 79.93%, p < 0.001), and this was higher when infrared laser was used, with a MD = − 2.561 (IC 95% − 4.656 to − 0.465; I2 = 90.73%, p = 0.017) (Fig. 4).

VAS, red laser T0 vs infrared laser T0: With regard to the laser modality used (red/infrared), in terms of pain at T0, no differences were found between the red laser group and the control group, MD = − 0.389 (IC 95% − 2.007 to 1.229; I2 = 88.98%, p = 0.638), nor between the infrared laser group and the control group, MD = − 0.336 (IC 95% − 1.075 to 0.402; I2 = 44.37%, p = 0.372). VAS, red laser Tf vs infrared laser Tf: At Tf, no significant differences were found between the red laser group and the control group, MD = − 1.555 (IC 95% − 3.569 to 0.459; I2 = 90.67%, p = 0.130); however, some differences were found between the infrared modality and the control group, MD = − 1.774 (IC 95% − 3.116 to − 0.432; I2 = 78.05%, p = 0.010). VAS, T0 vs Tf of subgroups, control vs red vs infrared: an improvement in pain was observed, MD = − 2.498 (IC 95% − 3.942 to − 1.053; I2 = 79.93%, p < 0.001), and this was higher when infrared laser was used, with a MD = − 2.561 (IC 95% − 4.656 to − 0.465; I2 = 90.73%, p = 0.017)

With regard to the quality of life at T0, no differences were found between the red laser group and the infrared laser group, MD = − 0.610 (IC 95% − 3.653 to 2.433; I2 = 42.79%, p = 0.694) and MD = − 2.329 (IC 95% − 5.869 to 1.212; I2 = 56.44%, p = 0.197), respectively. At Tf, significant differences were found between the two groups, with a higher MD in the red laser group, MD = − 4.577 (IC 95% − 7.666 to − 1.488; I2 = 64.39%, p = 0.004) than in the infrared group, MD = − 3.825 (IC 95% − 7.558 to − 0.092; I2 = 67.82%, p = 0.045). When we compared the Tf and T0 for the red laser, a greater improvement was observed in terms of quality of life for MD = − 8.144 (IC 95% − 12.082 to − 4.206; I2 = 64.22%, p = 0.027), compared to infrared MD = − 2.634 (IC 95% − 4.963 to − 0.305; I2 = 30.93%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5).

OHIP, red laser T0 vs infrared laser T0: With regard to the quality of life at T0, no differences were found between the red laser group and the infrared laser group, MD = − 0.610 (IC 95% − 3.653 to 2.433; I2 = 42.79%, p = 0.694) and MD = − 2.329 (IC 95% − 5.869 to 1.212; I2 = 56.44%, p = 0.197), respectively. OHIP laser Tf vs infrared laser Tf: At Tf, significant differences were found between the two groups, with a higher MD in the red laser group, MD = − 4.577 (IC 95% − 7.666 to − 1.488; I2 = 64.39%, p = 0.004) than in the infrared group, MD = − 3.825 (IC 95% − 7.558 to − 0.092; I2 = 67.82%, p = 0.045). OHIP, T0 vs Tf of subgroups, control vs red vs infrared: a greater improvement was observed in terms of quality of life for MD = − 8.144 (IC 95% − 12.082 to − 4.206; I2 = 64.22%, p = 0.027), compared to infrared MD = − 2.634 (IC 95% − 4.963 to − 0.305; I2 = 30.93%, p < 0.001)

Discussion

Currently, the basic therapeutic strategies for treating BMS focus on attempting to reduce pain and improve OHRQL by reducing xerostomia, stress level and anxiety [1]. The assessed studies measured pain and OHRQL using the VAS, or the NVS (0–10) and the OHIP-14 test, respectively.

The data obtained revealed soft laser as an important tool for managing BMS, and it was possible to prove its effectiveness, both in terms of reducing pain and in improving OHRQL, predominantly in the infrared modality.

Assessment of patient-perceived pain

Studies comparing the efficacy of red laser to ALA [36] and infrared laser and clonazepam [39] have presented similar outcomes for both treatments; however, the therapeutic outcomes for laser are slightly better and do not present any adverse effects. However, they also highlight the need for more randomised controlled trials to be conducted, which should be larger and include placebo-controlled therapeutic approaches.

The study by Valenzuela et al. [34] included three groups: group I and group II with active laser in infrared mode, and group III with laser off. The scores obtained from the patients treated with PBM showed a significant decrease in the severity of the burning sensation from the offset, while the control group did not report any significant differences at any time during the evaluation. No significant differences were reported between groups l and ll that received different doses of PBM. Spanemberg et al. [33], divided their population sample into four groups, but for this review, only groups ll, lll and IV, in which infrared, red, and laser off irradiation was used, respectively, with the same frequency and number of sessions, were considered. At the end of the treatment, the symptoms in all of the groups had decreased; however, this decrease differed significantly in the infrared group compared to the control group, and no significant differences were recorded between groups lll and lV, the red and off laser groups, respectively. Antonić et al.’s study published in 2017 also reported that the use of infrared laser was more effective than the use of red laser [40].

In a single study, Bardellini et al. [38] used a laser device with irradiation in the combined red and infrared wavelengths and reported that after the full course of therapy, patients treated with PBM reported a significant decrease in symptoms, which was maintained at the one-month follow-up, thus supporting the use of PBM for treating BMS.

The studies conducted by both Arbabi et al. [35] and Spanenberg et al. [33] showed that the use of PBM significantly decreases the burning sensation in patients’ suffering from BMS. A total of 100% of patients in de Pedro et al.’s study [37] experienced less pain at the end of treatment, an improvement that was maintained at the one-month follow-up, and which remained at 90% at the 4-month follow-up, with no variation in the control group. Contrary to these results, Škrinjar et al. [8] reported that all patients reported fewer burning symptoms after therapy, regardless as to whether their group underwent PBM or whether they formed part of the control group.

Evaluation of OHRQL, OHIP-14

De Pedro et al. [37] reported that the OHIP-14 scores decreased in the study group and increased in the control group when comparing the initial and final times; however, no significant differences between the two group were recorded. According to Bardellini et al. [38] and Arbabi et al. [35], the use of PBM was associated with an improvement (decrease) in the score and statistically significant differences existed between the treatment and control groups.

According to Valenzuela et al. [34], the groups of patients treated with PBM already showed a significant decrease at two weeks of treatment, a result which stabilised when comparing at the 2nd and 4th weeks, the weeks corresponding to the middle and end of treatment. No significant differences were observed between two groups that received different doses of PBM, and patients in the control group did not show significant differences at any of the evaluated time points.

In the study by Spanemberg et al. [33], there was a significant decrease in scores in both the PBM and control groups when comparing the assessment at beginning and at the end of treatment, and this was maintained at the eight-week follow-up. The difference was most significant in the infrared laser group, with no significant differences reported in the red laser and control groups.

Other studies that were found, but which were not included in the meta-analysis as they did not meet the inclusion criteria, also confirmed the role of laser in improving BMS. (Table 4) [26, 41,42,43].

Recently published systematic reviews on PBM [44, 45] include articles that were excluded from our study because they used pain scales with different scores [42], because they did not have a control group, or because the data provided was insufficient to be included in a meta-analysis [42, 46]. In this way, and after verifying the powerful biases of these studies, the present study was justified.

The diagnosis and treatment of BMS is still not very clear, as it is considered a multifactorial condition, with neuropathic, endocrinological, and psychological components [4]. This is why it is so important for a detailed medical history, which covers both general and oral health to be taken, which is usually followed by a set of ancillary investigations including a full blood count, serum iron determination, vitamin B12, folate and blood glucose levels. In addition, the patients’ knowledge of the chronic nature of the disease and the general absence of a history of malignancy is essential in order to limit anxiety and the risk of developing cancerophobia [1, 47].

Limitations of this study included the different final assessment time points (Tf ranging from 2 to 10 weeks), short follow-up periods, the relatively low number of participants and the high variability in the metrics used to assess outcomes with heterogeneous study designs. These limitations have been minimised thanks to a comprehensive design, very strict inclusion criteria and the thorough evaluation of the data provided.

Conclusion

The management of patients with BMS is difficult and often frustrating. The correct diagnosis of this syndrome and the exclusion of local or systemic factors that may be associated with burning mouth symptoms are essential, and, likewise, it is important to continue to search for new therapeutic alternatives. Although various treatment modalities have been proposed, such as pharmacological intervention, behavioural therapy and psychotherapy, there is no definitive treatment that always proves effective for the majority of patients with BMS. This systematic review and meta-analysis has concluded that amongst the different laser protocols, the ones in which red laser were used were statistically more effective in reducing BMS symptoms, in contrast to the results of studies in which red and infrared radiation were compared. Likewise, PBM resulted in a clear improvement in OHRQL compared to other treatment modalities. Further prospective studies with adequate epidemiological designs are required in order to better understand the relationship that exists between BMS and psychological and neuropathic factors.

References

Ślebioda Z, Lukaszewska-Kuska M, Dorocka-Bobkowska B (2020) Evaluation of the efficacy of treatment modalities in burning mouth syndrome-a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil 47:1435–1447. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13102

Sato Boku A, Kimura H, Tokura T et al (2021) Evaluation of patients suffered from burning mouth syndrome and persistent idiopathic facial pain using Japanese version PainDETECT questionnaire and depression scales. J Dent Sci 16:131–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2020.06.008

Forssell H, Teerijoki-Oksa T, Kotiranta U et al (2012) Pain and pain behavior in burning mouth syndrome: a pain diary study. J Orofac Pain 26:117–125

Imamura Y, Shinozaki T, Okada-Ogawa A et al (2019) An updated review on pathophysiology and management of burning mouth syndrome with endocrinological, psychological and neuropathic perspectives. J Oral Rehabil 46:574–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12795

Pereira JV, Normando AGC, Rodrigues-Fernandes CI et al (2021) The impact on quality of life in patients with burning mouth syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 131:186–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2020.11.019

Périer J-M, Boucher Y (2019) History of burning mouth syndrome (1800–1950): a review. Oral Dis 25:425–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.12860

Chimenos-Küstner E, de Luca-Monasterios F, Schemel-Suárez M et al (2017) Burning mouth syndrome and associated factors: a case-control retrospective study. Med Clin (Barc) 148:153–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2016.09.046

Škrinjar I, Lončar Brzak B, Vidranski V et al (2020) Salivary cortisol levels and burning symptoms in patients with burning mouth syndrome before and after low level laser therapy: a double blind controlled randomized clinical trial. Acta Stomatol Croat 54:44–50. https://doi.org/10.15644/asc54/1/5

Farag AM, Albuquerque R, Ariyawardana A et al (2019) World Workshop in Oral Medicine VII: Reporting of IMMPACT-recommended outcome domains in randomized controlled trials of burning mouth syndrome: a systematic review. Oral Dis 25:122–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13053

Jedel E, Elfström ML, Hägglin C (2021) Differences in personality, perceived stress and physical activity in women with burning mouth syndrome compared to controls. Scand J pain 21:183–190. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2020-0110

Adamo D, Pecoraro G, Fortuna G et al (2020) Assessment of oral health-related quality of life, measured by OHIP-14 and GOHAI, and psychological profiling in burning mouth syndrome: a case-control clinical study. J Oral Rehabil 47:42–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12864

Cárcamo Fonfría A, Gómez-Vicente L, Pedraza MI et al (2017) Burning mouth syndrome: clinical description, pathophysiological approach, and a new therapeutic option. Neurologia 32:219–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2015.10.008

Campello CP, Pellizzer EP, Vasconcelos BCdoE et al (2020) Evaluation of IL-6 levels and +3954 polymorphism of IL-1β in burning mouth syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Pathol Med 49:961–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.13018

Jääskeläinen SK (2012) Pathophysiology of primary burning mouth syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol 123:71–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2011.07.054

Lauria G, Majorana A, Borgna M et al (2005) Trigeminal small-fiber sensory neuropathy causes burning mouth syndrome. Pain 115:332–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.028

Madariaga VI, Tanaka H, Ernberg M (2020) Psychophysical characterisation of burning mouth syndrome-a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Rehabil 47:1590–1605. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.13028

Jääskeläinen SK, Teerijoki-Oksa T, Forssell H (2005) Neurophysiologic and quantitative sensory testing in the diagnosis of trigeminal neuropathy and neuropathic pain. Pain 117:349–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.028

Kolkka M, Forssell H, Virtanen A et al (2019) Neurophysiology and genetics of burning mouth syndrome. Eur J Pain 23:1153–1161. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1382

Scala A, Checchi L, Montevecchi M et al (2003) Update on burning mouth syndrome: overview and patient management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 14:275–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/154411130301400405

de Rivera R, Campillo E, López-López J, Chimenos-Küstner E (2010) Response to topical clonazepam in patients with burning mouth syndrome: a clinical study. Bull Group Int Rech Sci Stomatol Odontol 49:19–29

Cui Y, Xu H, Chen FM et al (2016) Efficacy evaluation of clonazepam for symptom remission in burning mouth syndrome: a meta-analysis. Oral Dis 22:503–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.12422

Kim M-J, Kim J, Kho H-S (2020) Treatment outcomes and related clinical characteristics in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Oral Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13693

Aggarwal A, Panat SR (2012) Burning mouth syndrome: a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. J Clin Exp Dent 4:e180–e185. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.50764

Coculescu EC, Tovaru S, Coculescu BI (2014) Epidemiological and etiological aspects of burning mouth syndrome. J Med Life 7:305–309

Chen Q, Shi Y, Jiang L et al (2020) Management of burning mouth syndrome: a position paper of the Chinese Society of Oral Medicine. J Oral Pathol Med 49:701–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.13082

Romeo U, Del Vecchio A, Capocci M et al (2010) The low level laser therapy in the management of neurological burning mouth syndrome. A pilot study Ann Stomatol (Roma) 1:14–18

de Pedro M, López-Pintor RM, de la Hoz-Aizpurua JL, et al (2020) Efficacy of low-level laser therapy for the therapeutic management of neuropathic orofacial pain: a systematic review. J oral facial pain headache 34:13–30 https://doi.org/10.11607/ofph.2310

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

da Costa Santos CM, de Mattos Pimenta CA, Nobre MRC (2007) The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 15:508–511. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-11692007000300023

Bruin J (2011) newtest: command to compute new test. UCLA: Statistical Consulting Group. https://stats.idre.ucla.edu/stata/ado/analysis/. Accessed 30 Jul 2021

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D et al (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 17:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327:557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

Spanemberg JC, López López J, de Figueiredo MAZ et al (2015) Efficacy of low-level laser therapy for the treatment of burning mouth syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. J Biomed Opt 20:98001. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.20.9.098001

Valenzuela S, Lopez-Jornet P (2017) Effects of low-level laser therapy on burning mouth syndrome. J Oral Rehabil 44:125–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12463

Arbabi-Kalati F, Bakhshani N-M, Rasti M (2015) Evaluation of the efficacy of low-level laser in improving the symptoms of burning mouth syndrome. J Clin Exp Dent 7:e524–e527. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.52298

Barbosa NG, Gonzaga AKG, de Sena Fernandes LL et al (2018) Evaluation of laser therapy and alpha-lipoic acid for the treatment of burning mouth syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Lasers Med Sci 33:1255–1262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-018-2472-2

de Pedro M, López-Pintor RM, Casañas E, Hernández G (2020) Effects of photobiomodulation with low-level laser therapy in burning mouth syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Oral Dis 26:1764–1776. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13443

Bardellini E, Amadori F, Conti G, Majorana A (2019) Efficacy of the photobiomodulation therapy in the treatment of the burning mouth syndrome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 24:e787–e791. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.23143

Arduino PG, Cafaro A, Garrone M et al (2016) A randomized pilot study to assess the safety and the value of low-level laser therapy versus clonazepam in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Lasers Med Sci 31:811–816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-016-1897-8

Antonić R, Brumini M, Vidovic I, Muhvić Urek M, Glazar I PS (2017) The effects of low level laser therapy on the management of chronic idiopathic orofacial pain: trigeminal neuralgia, temporomandibular disorders and burning mouth syndrome. Med Flum 53:61–67 https://doi.org/10.21860/medflum2017_173373

dos Santos L de FC, de Andrade SC, Nogueira GEC, et al (2015) Phototherapy on the treatment of burning mouth syndrome: a prospective analysis of 20 cases. Photochem Photobiol 91:1231–1236.https://doi.org/10.1111/php.12490

Sugaya NN, da Silva ÉFP, Kato IT et al (2016) Low intensity laser therapy in patients with burning mouth syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Braz Oral Res 30:e108. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2016.vol30.0108

Pezelj-Ribarić S, Kqiku L, Brumini G et al (2013) Proinflammatory cytokine levels in saliva in patients with burning mouth syndrome before and after treatment with low-level laser therapy. Lasers Med Sci 28:297–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-012-1149-5

Matos A-L, Silva P-U, Paranhos L-R et al (2021) Efficacy of the laser at low intensity on primary burning oral syndrome: a systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 26:e216–e225. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.24144

Zhang W, Hu L, Zhao W, et al (2021) Effectiveness of photobiomodulation in the treatment of primary burning mouth syndrome–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med Sci 36:39–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-020-03109-9

Spanemberg J-C, Segura-Egea J-J, Rodríguez-de Rivera-Campillo E et al (2019) Low-level laser therapy in patients with Burning Mouth Syndrome: a double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Exp Dent 11:e162–e169. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.55517

Reyad AA, Mishriky R, Girgis E (2020) Pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of burning mouth syndrome: a systematic review. Dent Med Probl 57:295–304. https://doi.org/10.17219/dmp/120991

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: This article was originally published with an email address: mepadin@hotmail.com but was rectified by the author to be changed to mepadin@uvigo.es.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Camolesi, G.C.V., Marichalar-Mendía, X., Padín-Iruegas, M.E. et al. Efficacy of photobiomodulation in reducing pain and improving the quality of life in patients with idiopathic burning mouth syndrome. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med Sci 37, 2123–2133 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-022-03518-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-022-03518-y